L9 Intracellular transport I - Nucleus, Mitochondria, Chloroplast, Peroxisome

一、Intracellular compartmentation

All Eukaryotic Cells Have the Same Basic Set of Membrane-enclosed Organelles

Intracellular membrane system increases membrane area to host biochemical reactions, intracellular membrane systems form enclosed compartments that are separate from the cytosol, thus creating functionally specialized aqueous spaces within the cell.

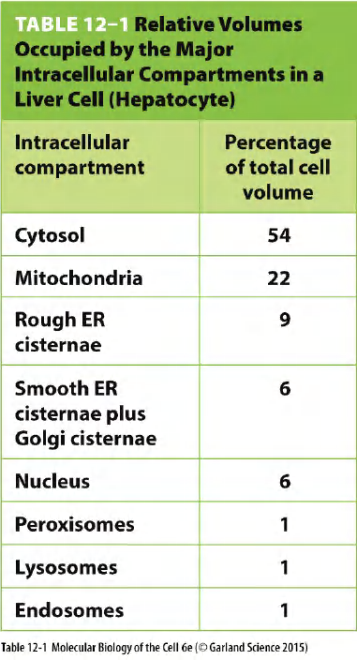

Relative volumes for each compartment in a liver cell:

- Volume of compartments

- represents about 50% of the total volume of the cell

- Almost half of that of that are mitochondria (in this liver cell)

- Each organelle contains its unique set of proteins that are characteristic of its distinct functions.

Different cell has different compartment volume ratio.

The size, shape, composition, and location are all important and regulated features of these organelles that ultimately contribute to the organelle’s function.

The eukaryotic cell has a much smaller ratio of surface area to volume, and its plasma membrane therefore presumably has too small an area to sustain the many vital functions that membranes perform.

Origin of internal membrane and membrane-bound organelles

The precursors of the first eukaryotic cells are thought to have been relatively simple cells that—like most bacterial and archaeal cells—have a plasma membrane but no internal membranes. The plasma membrane in such cells provides all membrane-dependent functions, including the pumping of ions, ATP synthesis, protein secretion, and lipid synthesis.

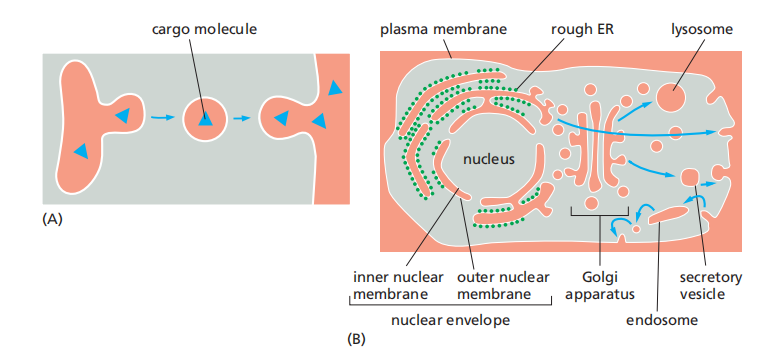

A hypothetical scheme for how the first eukaryotic cells, with a nucleus and ER, might have evolved by the invagination and pinching off of the plasma membrane of an ancestral cell is illustrated in Figure 12–3.This process would create membrane-enclosed organelles with an interior or lumen that is topologically equivalent.

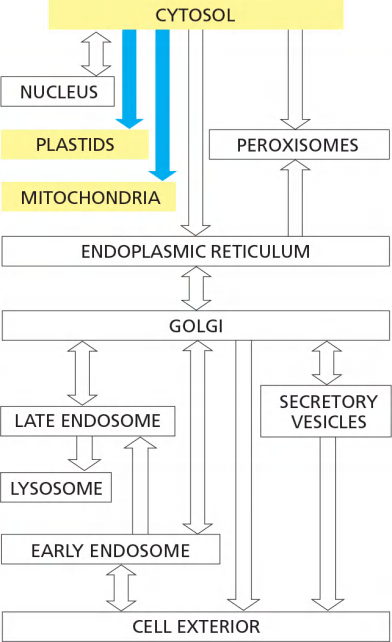

Compartments are said to be topologically equivalent if they can communicate with one another

We shall see that this topological relationship holds for all of the organelles involved in the secretory and endocytic pathways, including the ER, Golgi apparatus, endosomes, lysosomes, and peroxisomes. We can therefore think of all of these organelles as members of the same topologically equivalent compartment

Because this double membrane of nucleus is penetrated by nuclear pore complexes, the nuclear compartment is \topologically equivalent to the cytosol.

In contrast, the lumen of the ER is continuous with the space between the inner and outer nuclear membranes, and it is topologically equivalent to the extracellular space

Endogenous (e.g. invagination of plasma membrane)

Symbiotic (外源的)

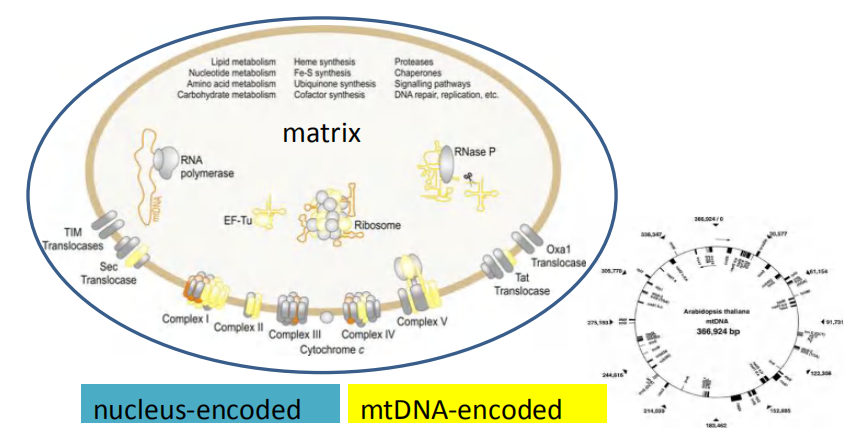

Mitochondria and plastids differ from the other membrane-enclosed organelles because they contain their own genomes

The nature of these genomes, and the close resemblance of the proteins in these organelles to those in some present-day bacteria, strongly suggest that mitochondria and plastids evolved from bacteria that were engulfed by other cells with which they initially lived in symbiosis

Most Organelles Cannot Be Constructed De Novo(再次): They Require Information in the Organelle Itself

- Information in the form of at least one distinct protein that preexists in the organelle membrane is also required

- this information is passed from parent cell to daughter cells in the form of the organelle itself.

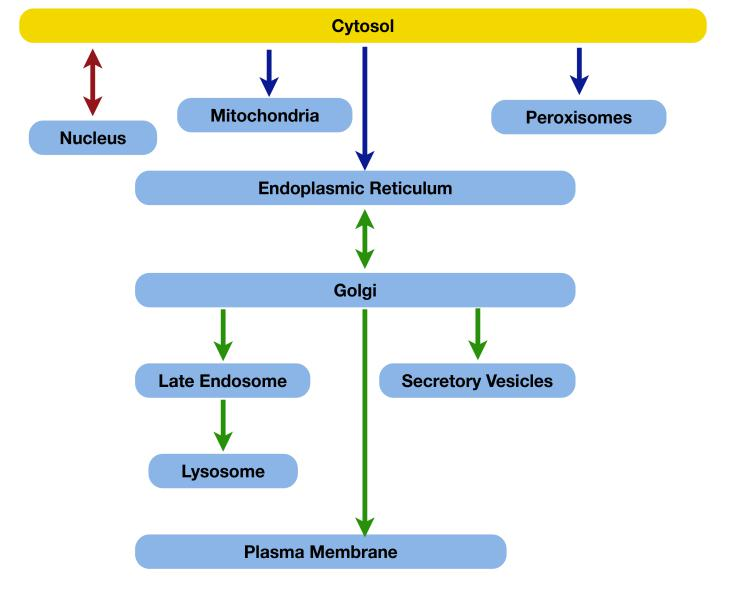

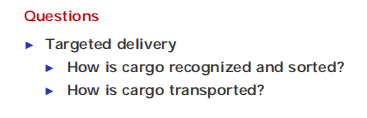

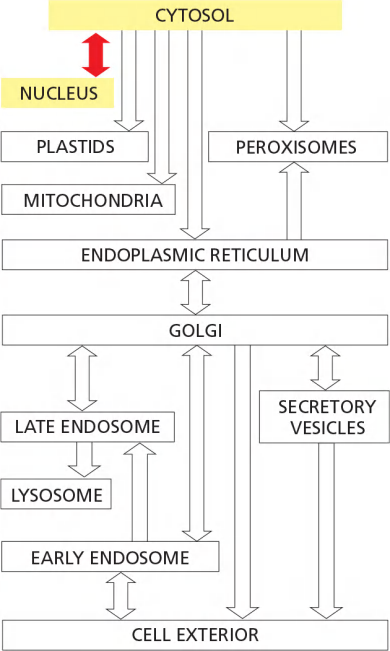

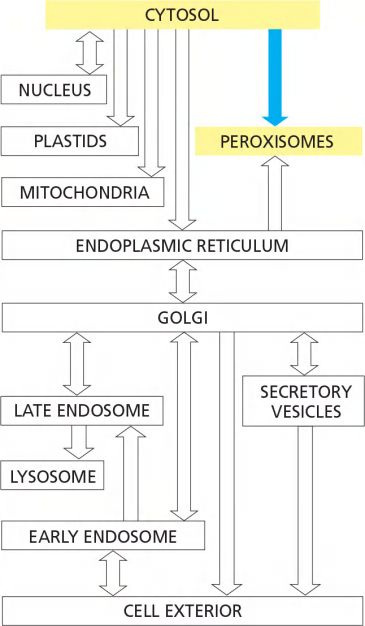

Proteins Transport Pathway

Proteins Can Move Between Compartments in Different Ways

Proteins are imported into organelles from cytosol or transported between organelles

Almost all proteins are synthesized in the cytosol and are transported later to their final destination due to their specific sorting signals

- Exception: some proteins from mitochondria and plastids!

1. Protein sorting: mechanisms of import

proteins are transported into other membrane-enclosed organelles only after their synthesis is complete, they are transported into the ER as they are synthesized.

3 types of mechanisms for macromolecule transport to cellular compartments:

“gated” transport (cytosal $\larr \rarr$ Nucleus) $\rarr$ “nuclear import/export signal (Lecture 9)

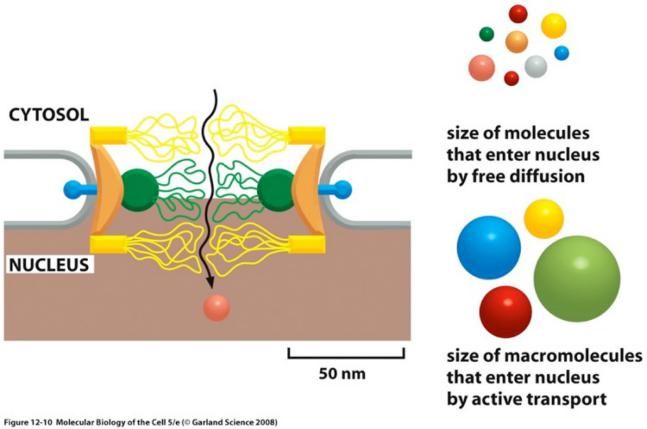

In gated transport, proteins and RNA molecules move between the cytosol and the nucleus through nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope.

The nuclear pore complexes function as selective gates that support the active transport of specific macromolecules and macromolecular assemblies between the two topologically equivalent spaces, although they also allow free diffusion of smaller molecules.

Protein translocation (unfolded protein “snake” through transmembrane translocators) $\rarr$ signal peptides, sorting signals/motifs (Lecture 9 and 10)

In protein translocation, transmembrane protein translocators directly transport specific proteins across a membrane from the cytosol into a space that is topologically distinct.

The transported protein molecule usually must unfold to snake through the translocator. The initial transport of selected proteins from the cytosol into the ER lumen or mitochondria, for example, occurs in this way.

- Integral membrane proteins often use the same translocators but translocate only partially across the membrane, so that the protein becomes embedded in the lipid bilayer.

Vesicular transport $\rarr$sorting signals/motifs (Lecture 11)

In vesicular transport, membrane-enclosed transport intermediates— which may be small, spherical transport vesicles or larger, irregularly shaped organelle fragments—ferry proteins from one topologically equivalent compartment to another.

The transport vesicles and fragments become loaded with a cargo of molecules derived from the lumen of one compartment as they bud and pinch off from its membrane; they discharge their cargo into a second compartment by fusing with the membrane enclosing that compartment (Figure 12–6).

- The transfer of soluble proteins from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, for example, occurs in this way. Because the transported proteins do not cross a membrane, vesicular transport can move proteins only between compartments that are topologically equivalent

Principles:

- Cargo recognition depends on sorting signals (signal sequences).

- Cargo transportation requires transport machinery.

- Protein without any kind of sorting signal remain in the cytosol.

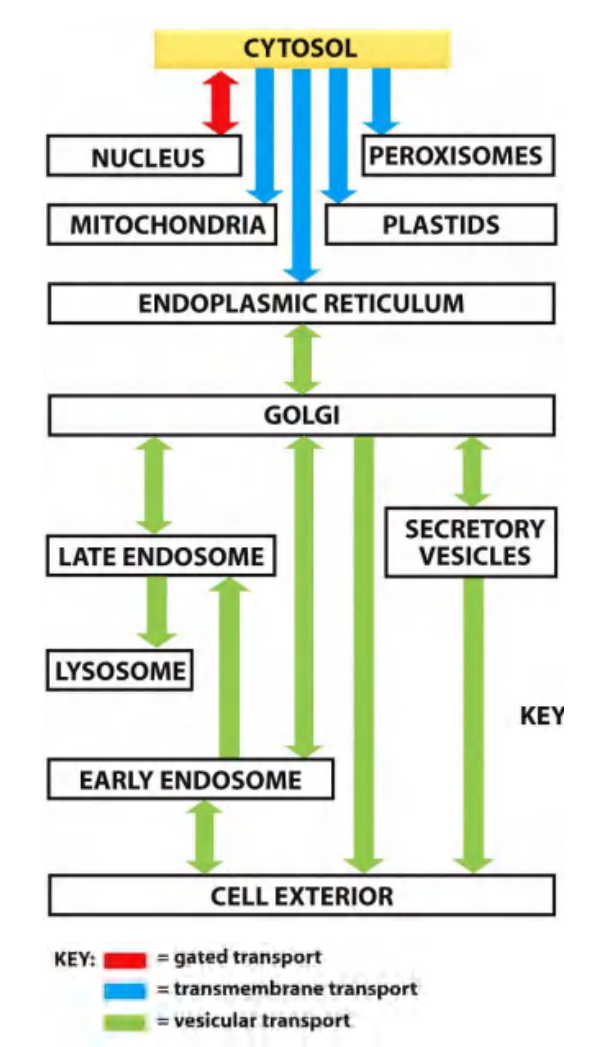

二、Signal sequences and targeted transport

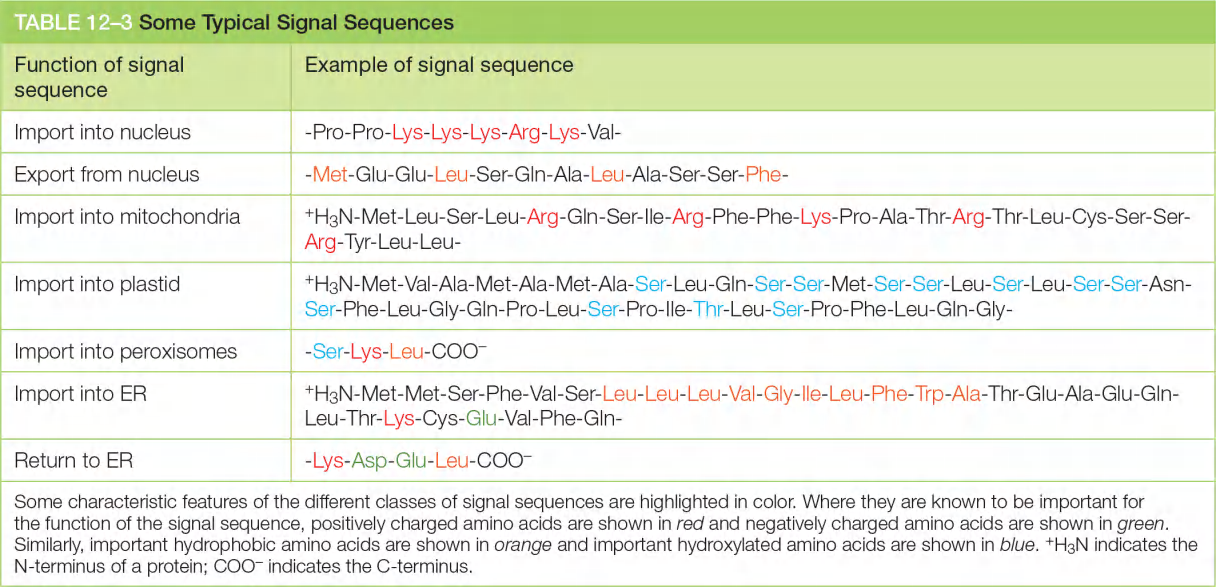

Signal sequences

Definition

Specific sorting signals: a stretch of amino acid sequence (typically 15-60 aa) which indicate where to put this protein.

Such signal sequences are often found at the N-terminus of the polypeptide chain, and in many cases specialized signal peptidases remove the signal sequence from the finished protein once the sorting process is complete

Signal sequences can also be internal stretches of amino acids, which remain part of the protein.

Sorting signals can also be composed of multiple internal amino acid sequences that form a specific three-dimensional arrangement of atoms on the protein’s surface; such signal patches are sometimes used for nuclear import and in vesicular transport.

- Often found at the N-terminus of the polypeptide chain

- In many cases can be removed by signal peptidases upon “arrival” (i. e. the sorting process is complete)

- Signal patches: a specific 3-dimensional arrangement of atoms on protein’s surface

Signal sequences are recognized by complementary sorting receptors that guide proteins to their appropriate destination, where the receptors unload their cargo.

Protein without any kind of sorting signal remain in the cytosol.

Organization/arrangement of sorting signals

图示的signal sequences在大部分情况是成立的,不代表具有相应的sequence就一定确定了转运方向,同样,没有图示的序列也不代表一定不是该转运方向。

三、Nuclear, mitochondria, chloroplast and peroxisome import

Nucleus-cytosol transport

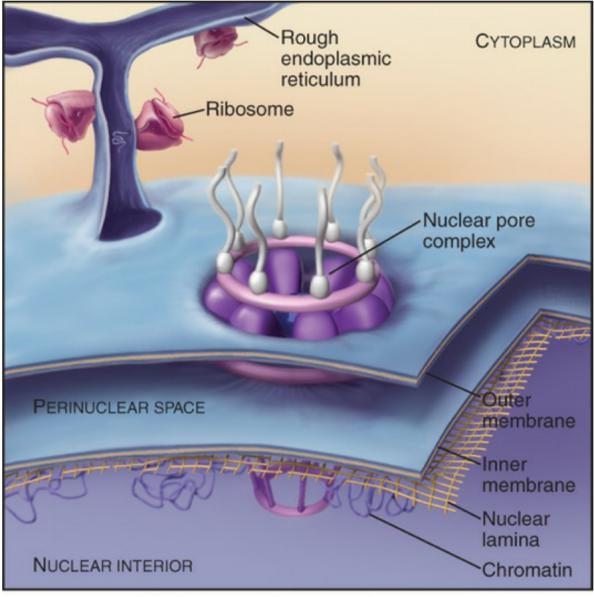

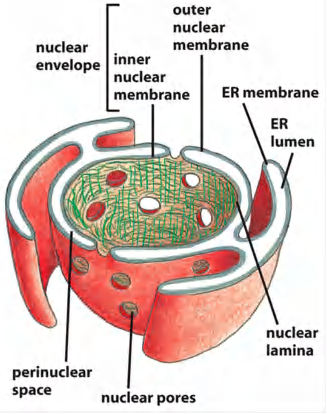

Nuclear envelope is a double lipid bilayer with supporting cytoskeleton and nuclear pores

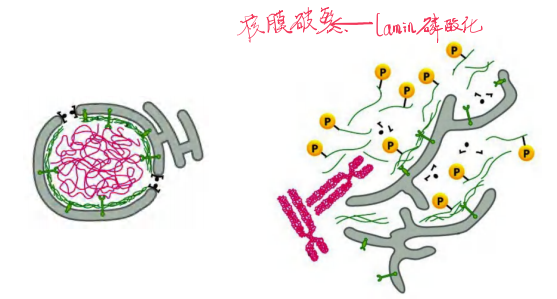

The Nuclear Lamina 提供一定的支撑作用

Phosphorylation of lamins leads to disassembly of nuclear envelope

Nuclear import and export

1. Structural components of nuclear membrane/envelope

Inner nuclear membrane proteins that bind to chromosome-binding proteins and nuclear lamina.

During Mitosis the Nuclear Envelope Disassembles

The nuclear lamina, located on the nuclear side of the inner nuclear membrane, is a meshwork of interconnected protein subunits called nuclear lamins.

- The lamina also interacts directly with chromatin, which itself interacts with transmembrane proteins of the inner nuclear membrane.

- Together with the lamina, these inner membrane proteins provide structural links between the DNA and the nuclear envelope.

Later in mitosis, the nuclear envelope reassembles on the surface of the daughter chromosomes.

Outer membrane is normally continuous with ER.

Structure of nucleus:

Inner membrane:

- anchor sites for chromatin and the nuclear lamina.

Outer membrane:

- continuation of ER

- with ribosomes: rough ER

- without ribosomes: smooth ER

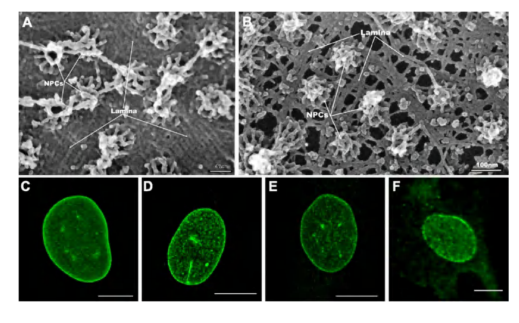

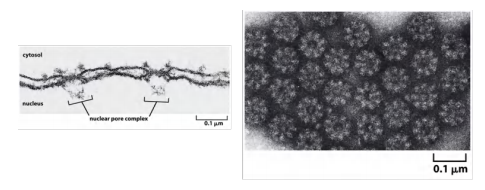

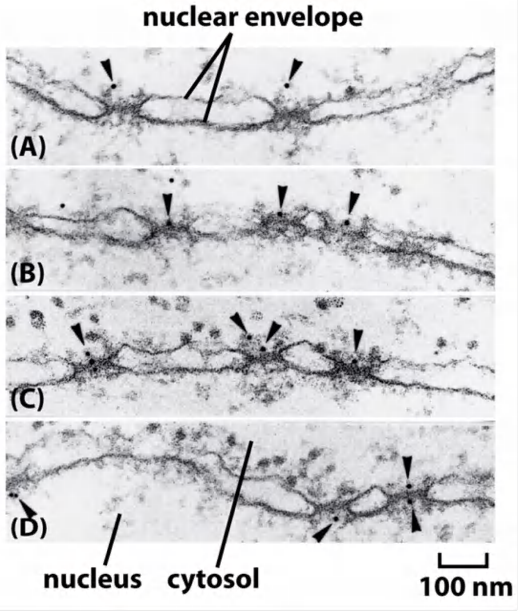

Nuclear pore complex (NPC): the gate of nuclear envelope

Nuclear Pore Complexes Perforate (穿孔于,在…上打眼) the Nuclear Envelop

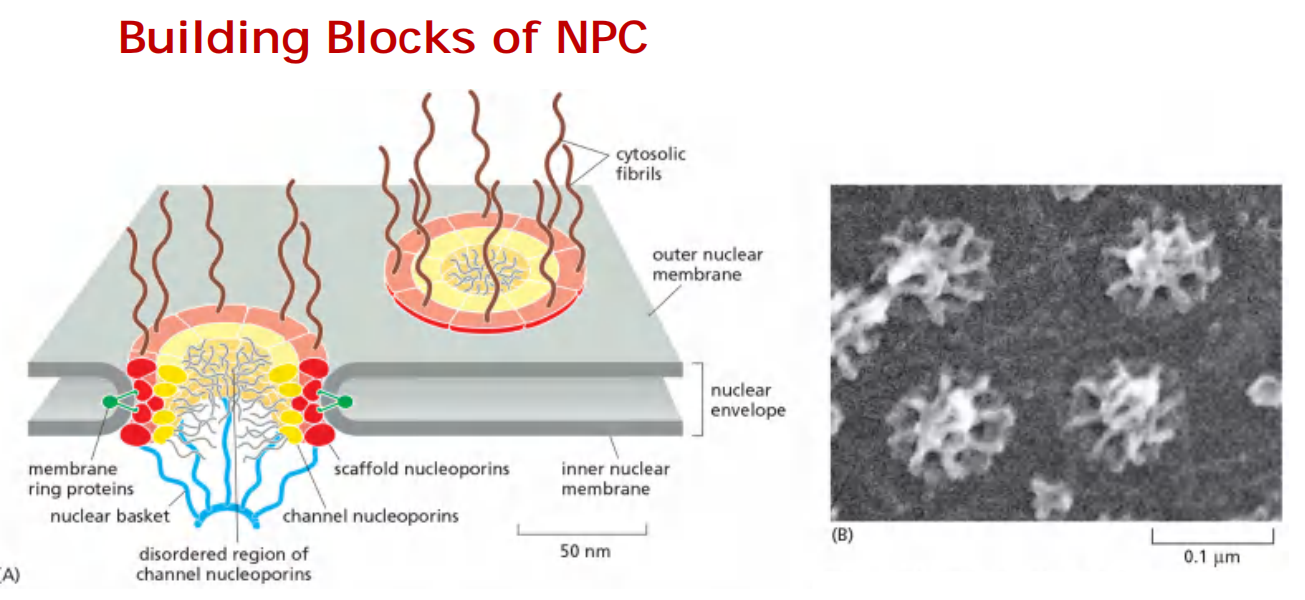

- Large and elaborate nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) perforate the nuclear envelope in all eukaryotes. Each NPC is composed of a set of approximately 30 different proteins, or nucleoporins

- Some of the scaffold nucleoporins (see Figure 12–8) are structurally related to vesicle coat protein complexes, such as clathrin and COPII coatomer

Transport between cytosol and nucleus occurs via the nuclear pore

The nuclear pore complex (NPC) is the gate into the nucleus, ∼ 3000-4000 NPC/cell

negative stained NPCs after detergent extraction

Nuclear pores complex structural organization/Features

Each NPC is a protein complex containing ∼ 30 types proteins called nucleoporins (phentolamine-glycine: FG-repeat).

- Each nucleoporin is present in multiple copies, which in total is 500-1000 nucleoporins/NPC (internal structural symmetry)

Some formed passages for small molecules, some participate in floating structures, some form a central channel with meshwork in the middle

Cytoplasmic fibrils(细胞质原纤维) and nuclear basket fibrils(核篮纤维) are proteins located around the entrance of pore

Nuclear pores are size selective channels

Features:

Transport at amazing speed: up to ∼1000 macromolecules/sec, in bi-directional manner

each NPC can transport up to 1000 macromolecules per second and can transport in both directions at the same time.

Each NPC contains aqueous passages(水通道), through which small water-soluble molecules can diffuse passively

Small molecules (<5 KDa) passive diffusion freely

Small molecules (5000 daltons or less) diffuse in so fast that we can consider the nuclear envelope freely permeable to them

Big molecules (> 60 KDa) cannot enter by passive diffusion

Proteins larger than 60,000 daltons cannot enter by passive diffusion

How are big proteins (DNA polymerases, RNA polymerases, ribosomal proteins, etc.) transported across nuclear envelope?

Nuclear import needs special proteins and sequences

Nuclear importing signals (nuclear localization signal, NLS):

- One or two short sequences that are rich in K (Lysine) and R (Arginine)

- Can be anywhere in the amino acid sequence.

- Can form loops or patches on the protein surface (3-D structure, signal patch)

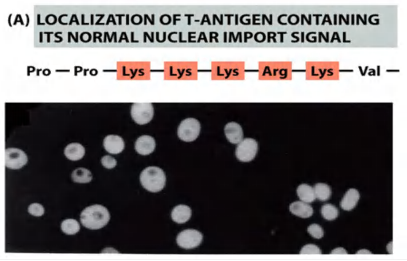

Nuclear Localization Signals Direct Nuclear Proteins to the Nucleus

- Sorting signals called nuclear localization signals (NLSs) are responsible for the selectivity of this active nuclear import process

- Nuclear localization signals can be located almost anywhere in the amino acid sequence and are thought to form loops or patches on the protein surface

Mutation of key amino acids in the NLS destroys the signal

- the mutant protein will lose its nuclear localization and remains in the cytosol!

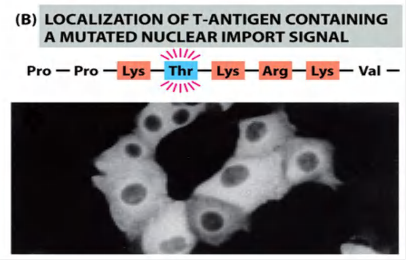

(1) Visualizing active import through NPCs

Gold particles were coated with NLS-peptides (time-course experiment)

Coated gold particles were injected into cells. Cells were fixed at different time points after injection to track gold particle movement

Coated gold particle can be seen to:

- interact with NPC (A-C)

- get through the NPC (D)

2. Substances That Can be Transported

Molecules that are transport (imported) into the nucleus:

- histones

- DNA/RNA polymerases

- gene regulatory proteins (transcription factors)

- RNA processing proteins

- ribosomal proteins, etc.

Molecules that are transported (exported) out of the nucleus:

- mature RNAs

- tRNAs

- pre-ribosome subunits

- proteins, etc

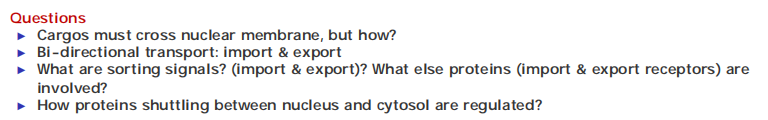

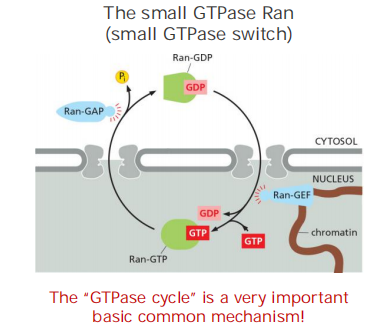

3. Nuclear import receptors (importins)

To initiate nuclear import, most nuclear localization signals must be recognized by nuclear import receptors, sometimes called importins, most of which are encoded by a family of related genes

Nuclear import receptors do not always bind to nuclear proteins directly. Additional adaptor proteins can form a bridge between the import receptors and the nuclear localization signals on the proteins to be transported

Features

- Soluble cytosolic proteins

- Bridging NLS-cargo and FG-repeats of nucleoporins at the NPC

- Some receptors use adaptor proteins for “bridging”: the adaptors recognize NLS-cargo proteins and have also an own NLS to interact with the receptor

4. Nuclear export

The transport system relies on nuclear export signals on the macromolecules to be exported, as well as on complementary nuclear export receptors, or exportins

Many nuclear export receptors are structurally related to nuclear import receptors, and they are encoded by the same gene family of nuclear transport receptors, or karyopherins(胡萝卜素)

Features

Nuclear export signals relatively poorly characterized, not many facts are known

Some have a leucine rich sequence

Nuclear export receptors facilitates export.

Nuclear export receptors are structurally related to nuclear import receptors.

Role of GTPase

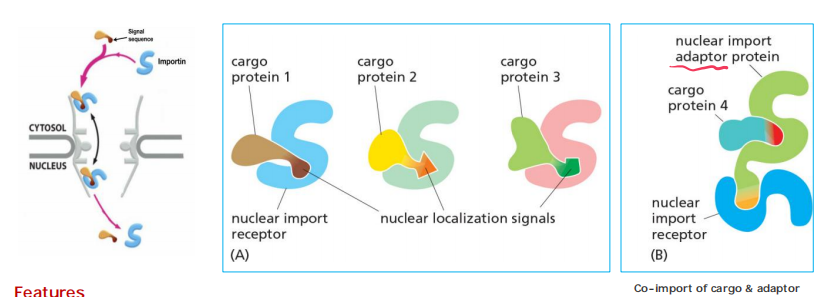

Nuclear import/export consume energy, which is controlled by Ran GTPase (nuclear transport cycle)

The “GTPase cycle” of RAN:

- Ran-GDP (cytosol)

- Ran-GTP (nucleus)

A cytosolic GTPase-activating protein (GAP) triggers GTP hydrolysis and thus converts Ran-GTP to Ran-GDP,

A nuclear guanine exchange factor (GEF) promotes the exchange of GDP for GTP and thus converts Ran-GDP to Ran-GTP.

Because Ran-GAP is located in the cytosol and Ran-GEF is located in the nucleus where it is anchored to chromatin, the cytosol contains mainly Ran-GDP, and the nucleus contains mainly Ran-GTP

This gradient of the two conformational forms of Ran drives nuclear transport in the appropriate direction

- This occurs whether or not these receptors are loaded with appropriate cargo

Because the Ran-GDP in the cytosol does not bind to import (or export) receptors, unloading occurs only on the nuclear side of the NPC

Transport occurs according to gradient cytosol/nucleus

- Cytosolic Ran-GDP is “activated” by a Ran-GEF (Guanine nucleotide exchange factor) in the nucleus. This converts Ran-GDP to Ran-GTP

- In the cytosol, Ran-GTP is stimulated by Ran-GAP (GTPase-activating protein) to hydrolyse its GTP (conversion to Ran-GDP)

In addition to its crucial role in nuclear transport, the Ran GTPase also acts as a positional marker for chromatin during cell division, when the nuclear and cytosolic components intermix.

Because Ran-GEF remains bound to chromatin when the nuclear envelope breaks down, Ran molecules close to chromatin are mainly in their GTP-bound conformation

Nuclear export occurs by a similar mechanism, except that Ran-GTP in the nucleus promotes cargo binding to the export receptor, rather than promoting cargo dissociation

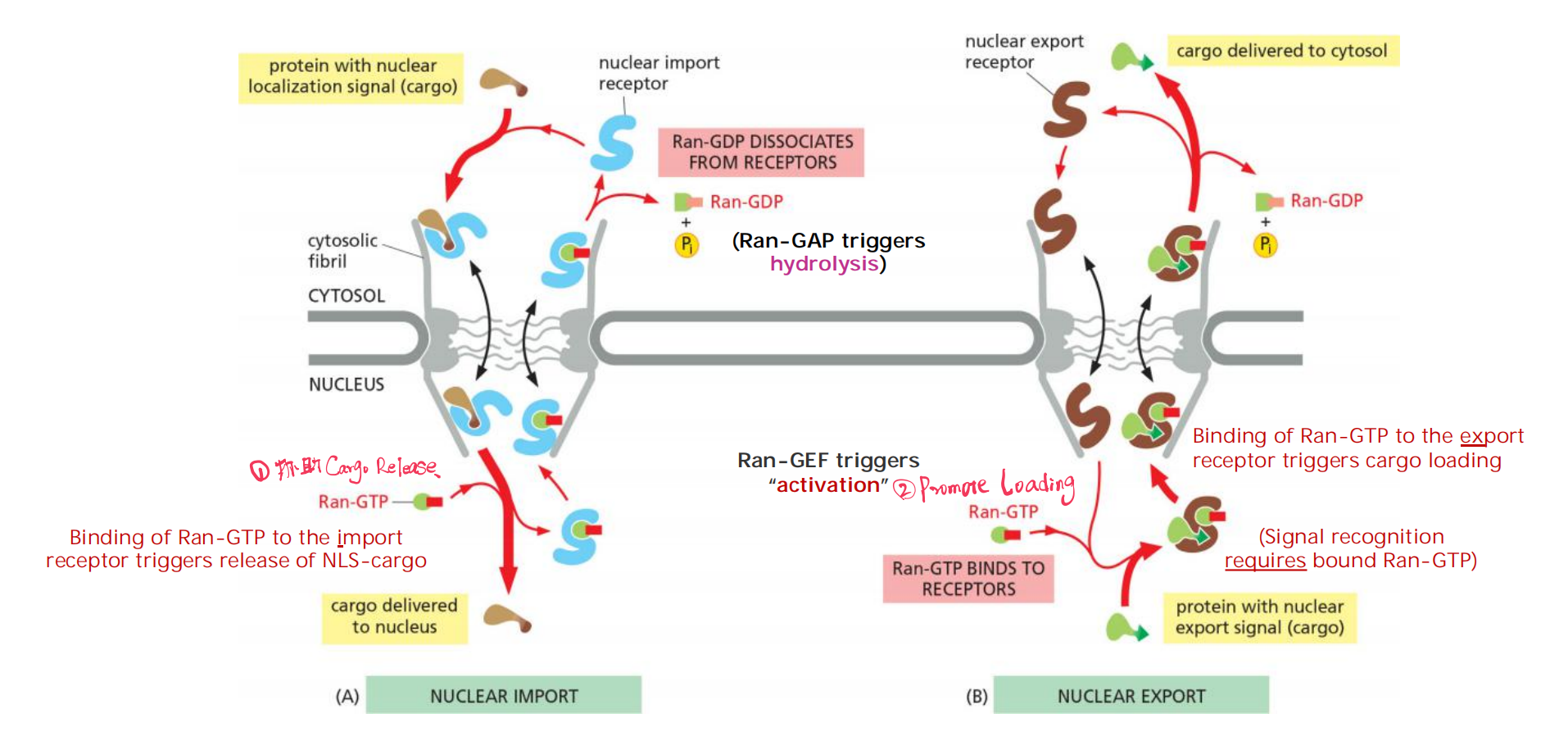

5. Shuttling Proteins

Some proteins contain both nuclear localization signals and nuclear export signals. These proteins continually shuttle back and forth between the nucleus and the cytosol.

The relative rates of their import and export determine the steady state localization of such shuttling proteins

Shuttling proteins can be regulated through protein phosphorylation

In many cases, cells control transport by regulating nuclear localization and export signals—turning them on or off, often by phosphorylation of amino acids close to the signal sequences

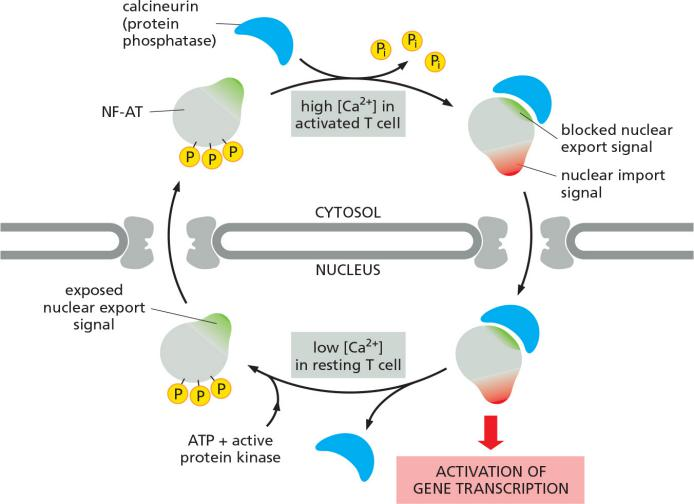

The control of nuclear import of the transcription factor NF-AT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) during T cell activation is due to altered Ca2+ levels:

- high Ca2+ activates

- declining/low Ca2+ levels deactivate

For example:

Nuclear import (X) and nuclear export (X) signal can be masked by its phosphorylation states.

Regulation over time, not via the location, due to altered Ca2+ levels dependent on the physiological condition

signal sequence 附近被磷酸化之后,NF-AT 蛋白上的 nuclear export signal 显现出来,nuclear import signal 被block掉,因此蛋白被转运出细胞;去磷酸化之后 nuclear import signal 显现出来,nuclear export signal 被block掉,因此蛋白被转运进细胞。

Shuttling proteins can be regulated metabolically

Other transcription regulators are bound to inhibitory cytosolic proteins that either anchor them in the cytosol (through interactions with the cytoskeleton or specific organelles) or mask their nuclear localization signals so that they cannot interact with nuclear import receptors.

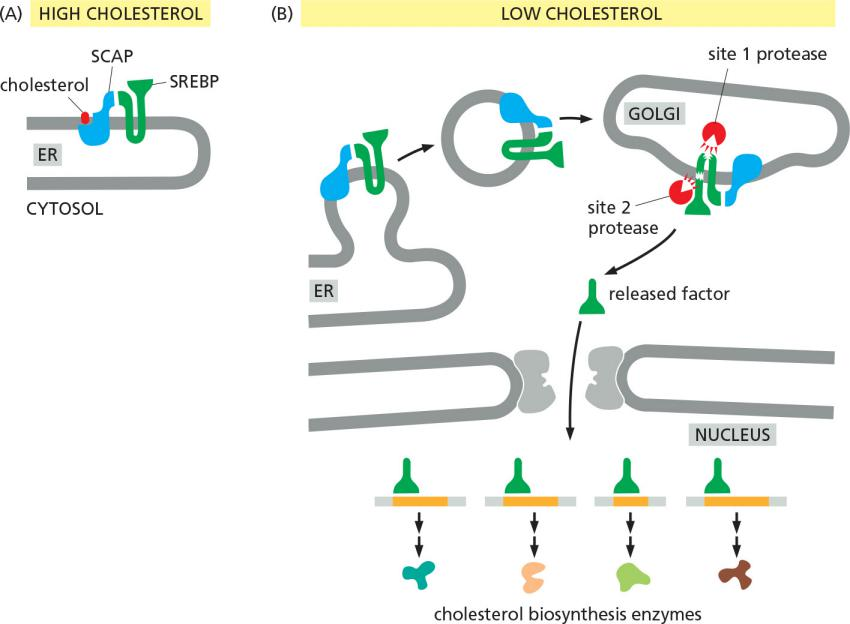

e.g. cholesterol level in the cell regulate cholesterol biogenesis: negative feedback

SREBP: steroid response element binding protein

SCAP: SREBP cleavage activation protein

7. Nucleic Acid Transport

Cells control the export of RNAs from the nucleus in a similar way. snRNAs, miRNAs, and tRNAs bind to the same family of nuclear export receptors just discussed, and they use the same Ran-GTP gradient to fuel the transport process.

The export of mRNAs out of the nucleus uses a different mechanism. mRNAs are exported as large assemblies with nuclear proteins

- Newly transcribed messenger RNA and ribosomal RNA are exported from the nucleus as parts of large ribonucleoprotein complexes.

- Because nuclear localization signals are not removed, nuclear proteins can be imported repeatedly, as is required each time that the nucleus reassembles after mitosis

8. Summary: Nuclear and cytoplasmic Protein Transport

Nuclear Pores ~9 nm formed from nucleoporin proteins

Smaller proteins (~5 kDa or less) may diffuse freely; larger proteins must be imported by “gated pore” mechanism

Proteins targeted for nucleus have nuclear localization signals

Most NLS must be recognized & bound by nuclear import receptors or nuclear export receptors

Transport to mitochondria and chloroplasts

Translocation into Mitochondria Depends on Signal Sequences and Protein Translocators

1. Protein import into mitochondria

New mitochondria and chloroplasts are produced by the growth of pre-existing organelles, followed by fission (discussed in Chapter 14). The growth depends mainly on the import of proteins from the cytosol

Why is targeting to mitochondria and chloroplasts important?

- Even though mitochondria and chloroplast have their own genome and protein synthesis machinery, the majority of proteins are encoded in the nucleus and are therefore synthesized in the cytosol and then imported afterwards.

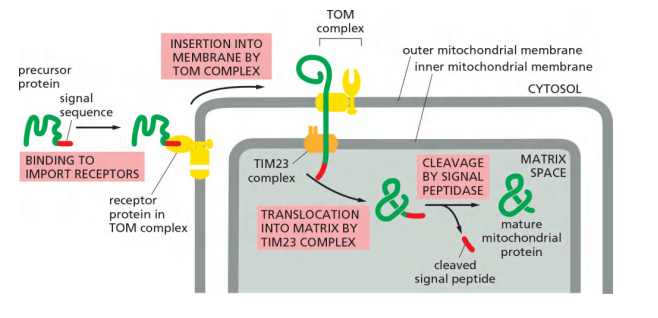

mitochondrial proteins are first fully synthesized as mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol and then translocated into mitochondria by a post-translational mechanism

- Many proteins entering the matrix space contain a signal sequence at their N-terminus that a signal peptidase rapidly removes after import.

- Other imported proteins, including all outer membrane and many inner membrane and intermembrane space proteins, have internal signal sequences that are not removed.

Transport to mitochondria and chloroplasts Features

Features

- Proteins with appropriate signal sequence squeeze through protein translocators.

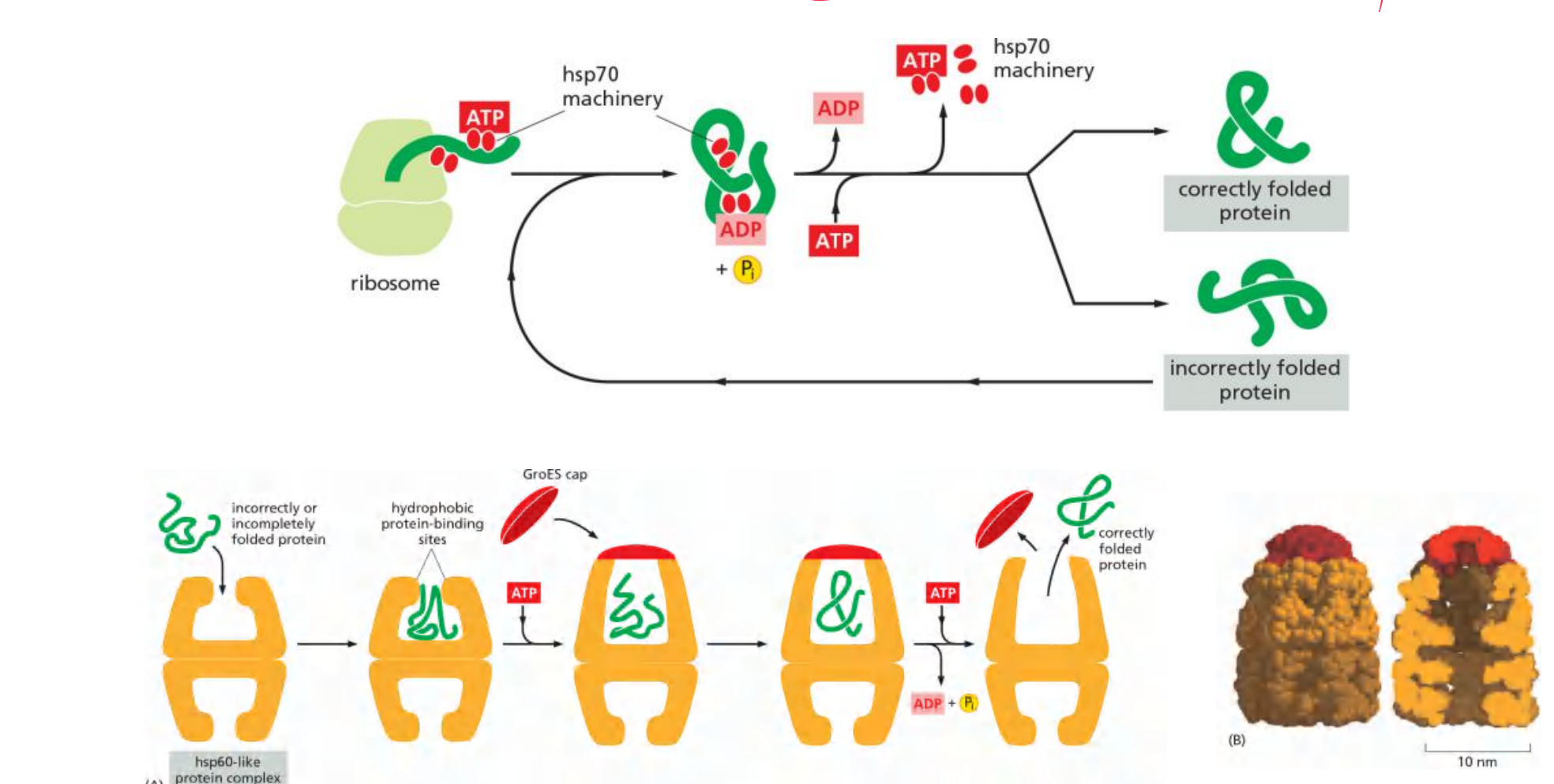

- They unfold and re-fold later with the help of chaperones proteins

Molecular chaperons facilitate protein folding

Many molecular chaperones are called heat-shock proteins (hsp) 温度升高时会增量表达

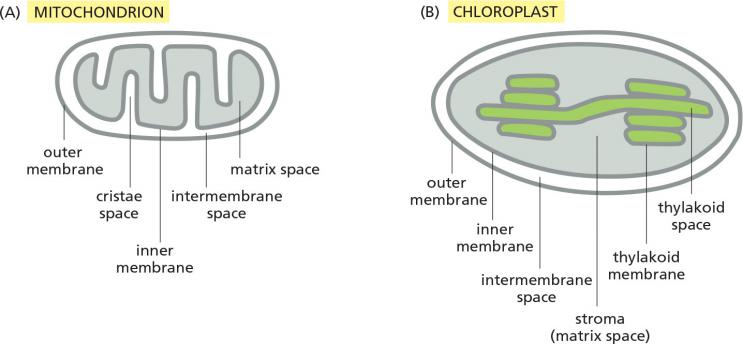

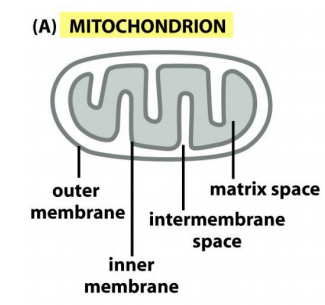

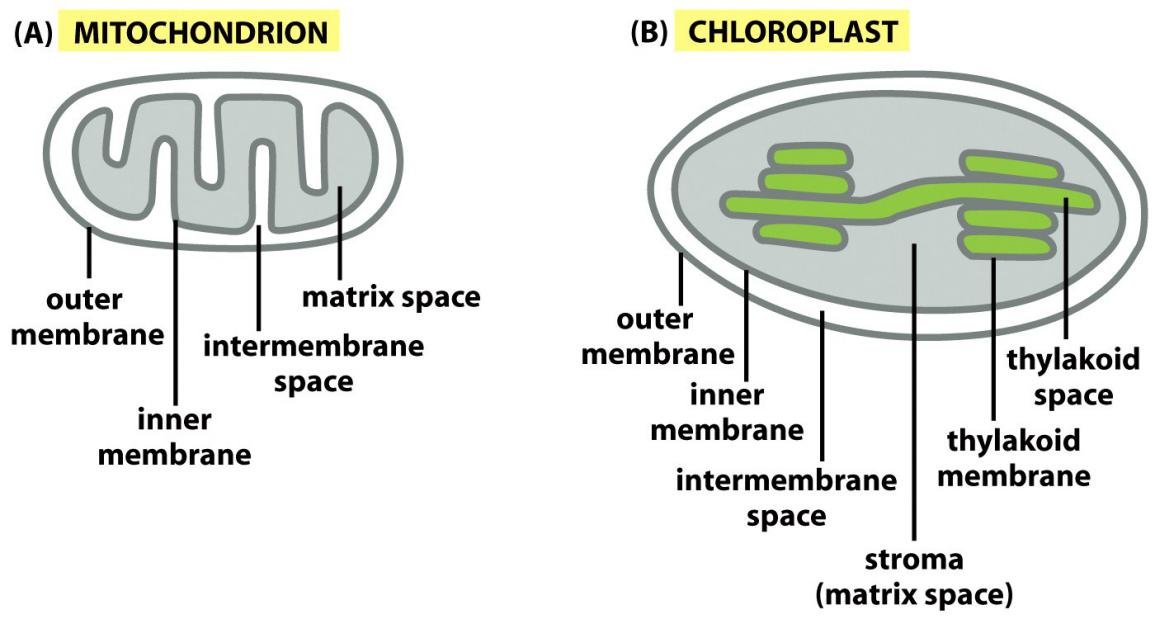

Protein localization in mitochondria

Mitochondria have two independent reaction rooms:

IMS (intermembrane space) and matrix

Targeting to mitochondria includes targeting to:

- OM: Outer membrane

- IMS: Intermembrane space

- IM: Inner membrane

- matrix

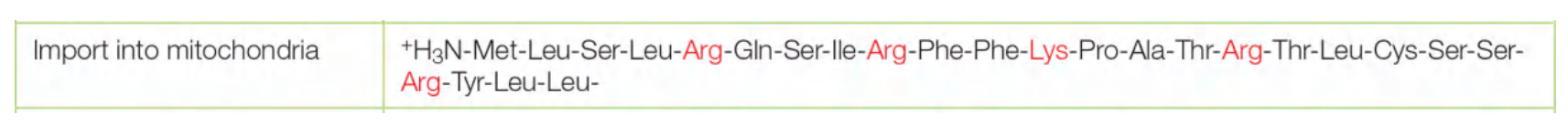

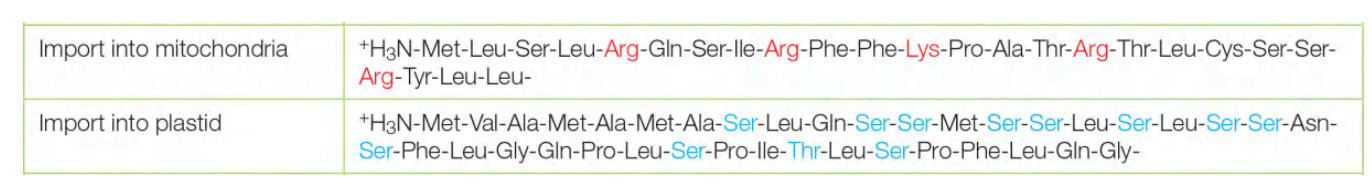

2. Mitochondria localization signal

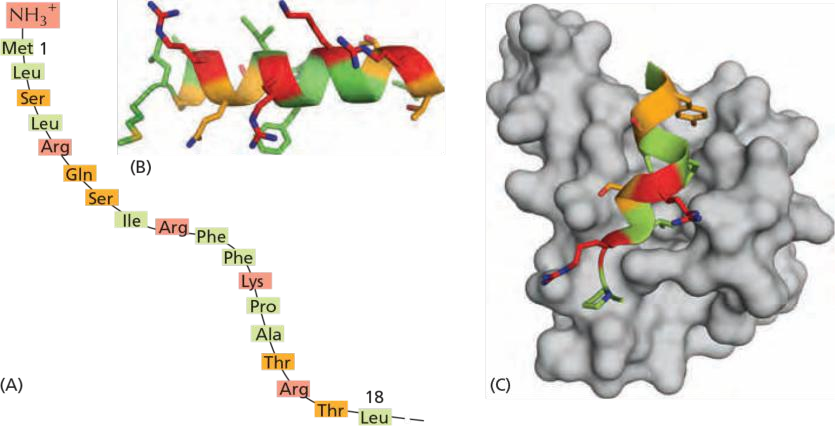

The signal sequences that direct precursor proteins into the mitochondrial matrix space are best understood.

- They all form an amphiphilic α helix, in which positively charged residues cluster on one side of the helix, while uncharged hydrophobic residues cluster on the opposite side.

Features:

Mitochondria precursor proteins are fully synthesized in the cytosol before their import

Chaperones keep the proteins in an unfolded “import-competent” state and guide them to the TOM/TOC complexes, their import is referred to as “transmembrane transport”

An N-terminal peptide directs many precursor proteins to matrix, then, this signal peptide it is cleaved upon arrival

An internal peptide directs all precursor proteins into the outer membrane, many to be in the inner membrane.

need for a receptor protein

Specific receptor proteins that initiate protein translocation recognize this configuration rather than the precise amino acid sequence of the signal sequence

The mitochondrial signal an amino acid sequence that forms an amphiphilic α-helix.

- one side of the helix is hydrophilic the other side is hydrophobic

Positively charged amino acid on one side, Nonpolar amino acid on other side

The amphiphilic α-helix of the signal binds with its hydrophobic face to a hydrophobic groove in the receptor

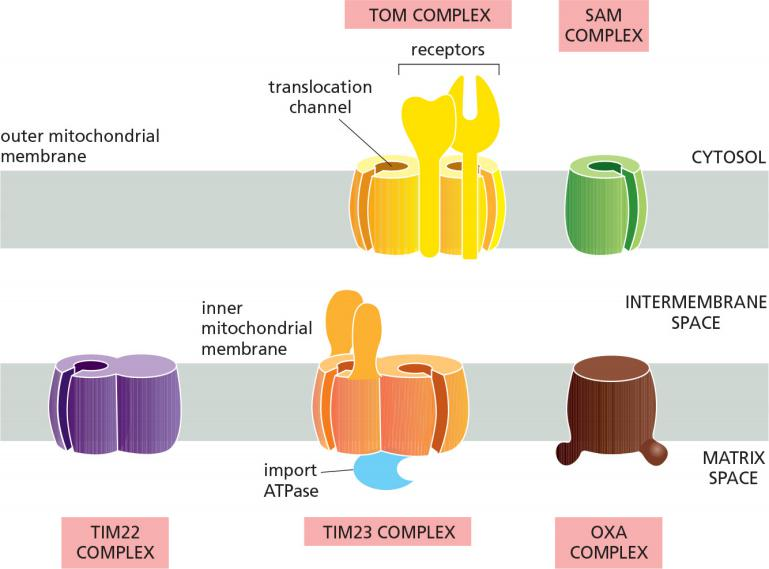

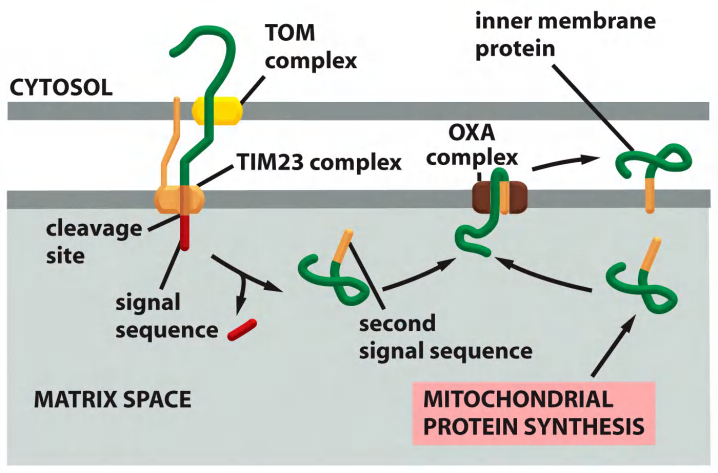

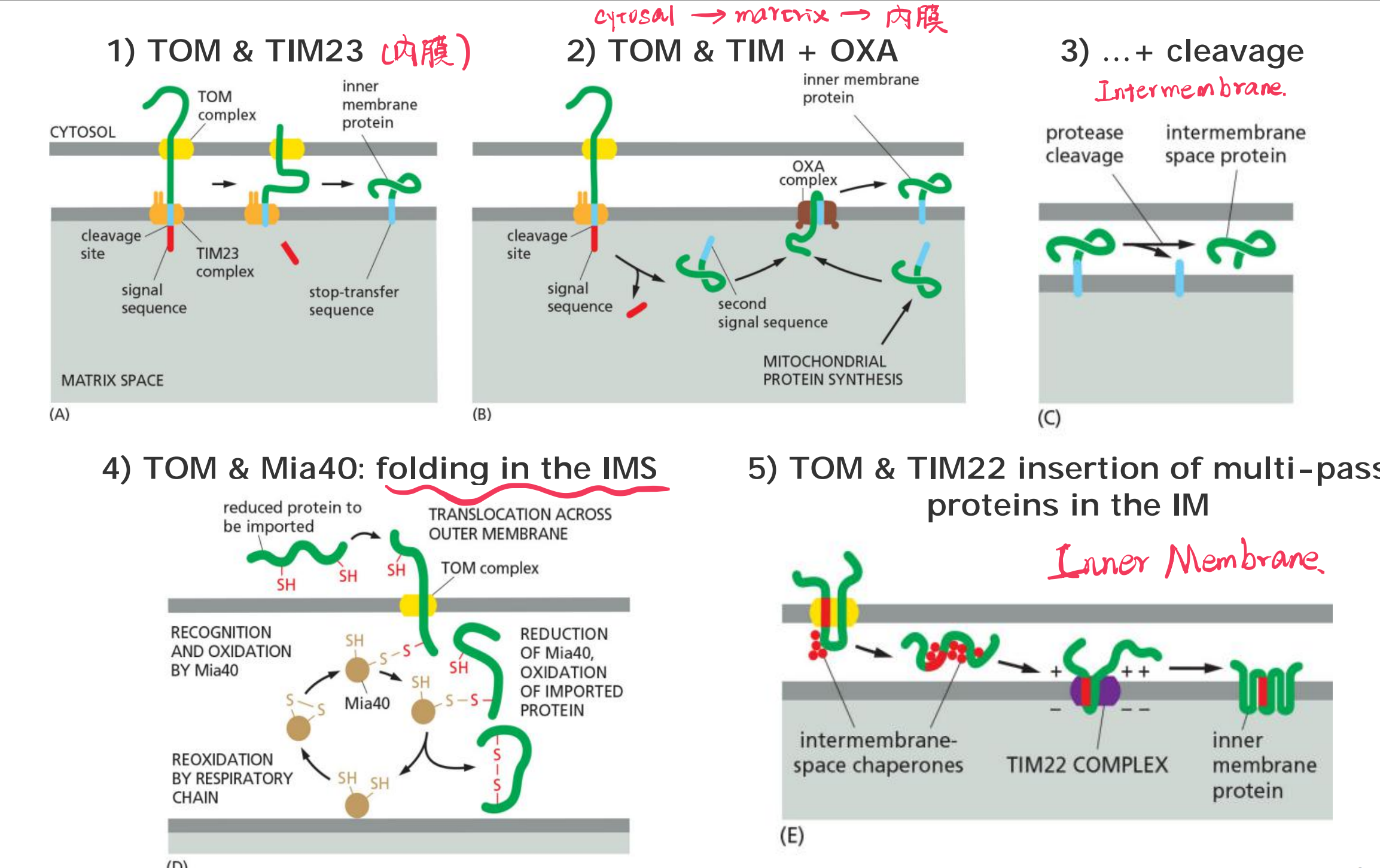

Different Protein Translocators

Different protein translocators facilitate protein import and transport across the membranes in mitochondria

- TOM (Translocase outer membrane mitochondria) complex transfers proteins across the outer mitochondria membrane.

- TIM23 (Translocase inner membrane mitochondria) complex transfer proteins across the inner mitochondria membrane.

- For single pass transmembrane protein

- TOM & TIM23, both function as receptors for signal peptides

- can form a transmembrane channels spanning both membranes

- SAM (sorting and assembly complex mitochondria) complex helps to insert/fold properly the β-barrel proteins in outer membrane.

- TIM22, acts similar to TIM23

- Acts for multi pass transmembrane protein

- OXA (Oxidase assembly machinery) complex

- helps to insert mitochondria-synthesized proteins and others transported proteins from the matrix into the inner membrane

(1) Proteins import into the mitochondrial matrix via TOM and TIM23

The precursor of the matrix protein is passing both membranes at the same time; the signal sequence works for TOM and for TIM23.

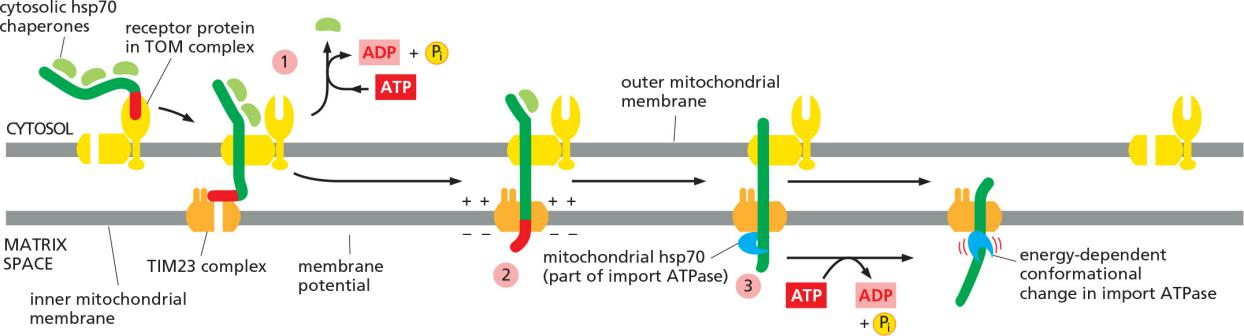

Protein import into the mitochondrial matrix consume energy

ATP hydrolysis and the membrane potential drive the protein import into the mitochondrial matrix.

- ATP is consumed by the chaperones (cytosolic hsp70) for “releasing” the precursor protein

- Chaperones hydrolase ATP via an ATPase domain!

Translocation of the positively charged signal sequence depends on the membrane potential.

Mitochondrial hsp70 chaperon also consumes ATP during “pulling” (binding & release cycles) the precursor protein inside

The mitochondrial hsp70 is part of a multisubunit protein assembly that is bound to the matrix side of the TIM23 complex and acts as a motor to pull the precursor protein into the matrix space.

The hsp70 then undergoes a conformational change and releases the protein chain in an ATP-dependent step, exerting a ratcheting/pulling force on the protein being imported

After the initial interaction with mitochondrial hsp70, many imported matrix proteins are passed on to another chaperone protein, mitochondrial hsp60.

As discussed in Chapter 6, hsp60 helps the unfolded polypeptide chain to fold by binding and releasing it through cycles of ATP hydrolysis.

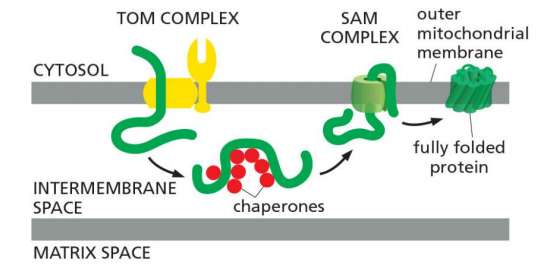

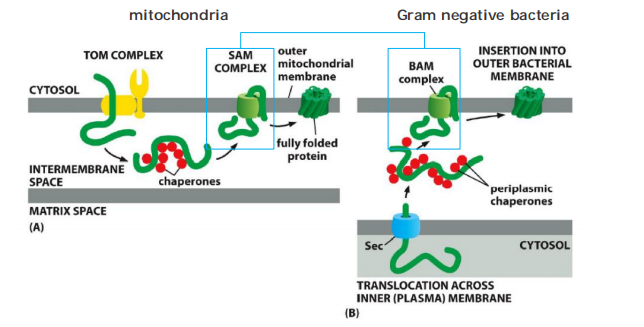

(2) Outer membrane porins (β-barrel proteins) are inserted with the help of SAM via the intermembrane space (IMS)

Unfolded β-barrel proteins are translocated via TOM to the intermembrane space (IM) where they are stabilized by chaperones.

Then, they are inserted in to the outer membrane via the SAM complex, which also aids folding (finally).

the TOM complex cannot integrate porins into the lipid bilayer

They then bind to the SAM complex in the outer membrane, which both inserts them into the outer membrane and helps them fold properly

Bacteria and mitochondria use similar mechanisms to insert porins (β-barrel proteins) into the outer membrane, but…

- The proteins have different origins in mitochondria compared to bacteria.

- Mitochondria: proteins reach the IMS from the “outside” via TOM

- Bacteria: proteins reach the peri-bacterial space(细菌周围的空间) from “inside” via Sec complex, the bacteria use the BAM complex to translocate the protein from intermembrane space into outer membrane

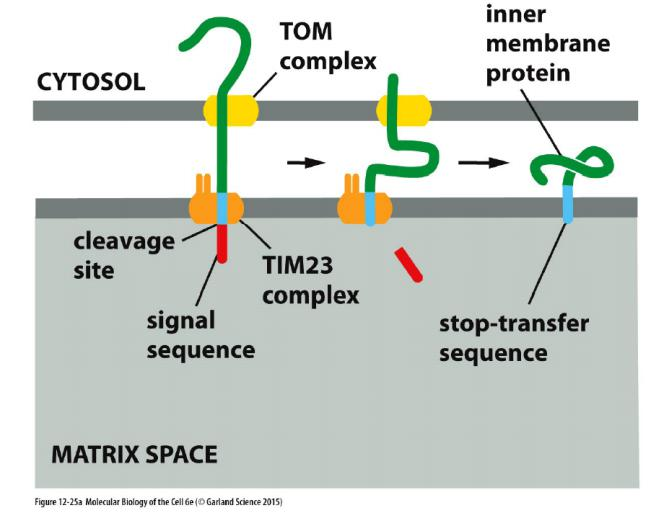

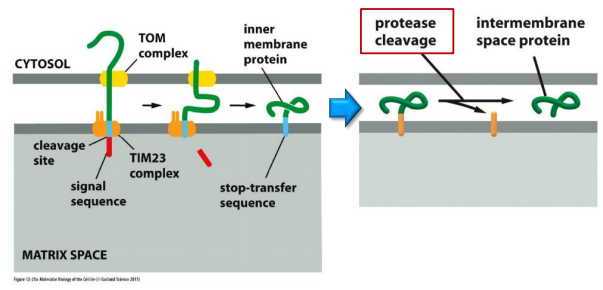

(3) Protein import into the inner membrane (IM)

Targeting of single-pass transmembrane proteins:

- TOM

- TIM23

- signal sequence

- hydrophobic stop-transfer sequence

A hydrophobic amino acid sequence, strategically placed after the N-terminal signal sequence, acts as a stop-transfer sequence, preventing further translocation across the inner membrane

- A matrix signal peptidase then removes the N-terminal signal sequence, exposing a hydrophobic sequence at the new N-terminus.

- Many proteins that use these pathways to the inner membrane remain anchored there through their hydrophobic signal sequence

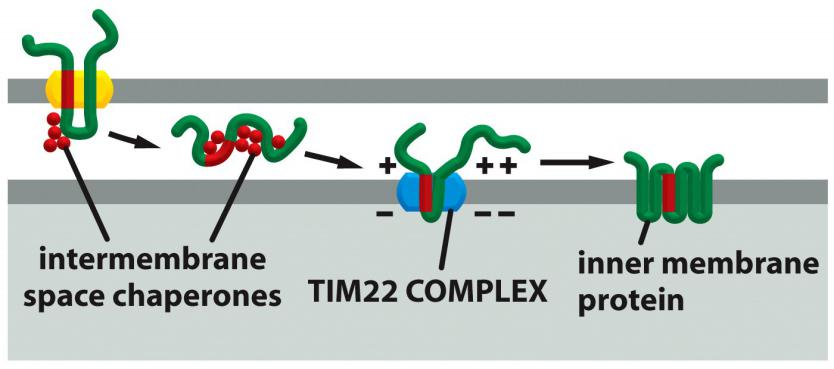

Targeting of multi-pass transmembrane proteins

TOM

Chaperones

TIM22

Internal signal sequence

Multi-pass IM proteins that function as metabolite transporters contain internal signal sequences and sneak through the TOM complex as a loop.

IMS chaperones bind the precursor in the intermembrane space and guide the protein to the TIM22 complex, which is specialized for the insertion of multi-pass IM proteins.

(4) Protein import into the inner membrane (IM) from the matrix

Protein import into the IM from the matrix (e.g. oxidase on the electron transport chain)

Extremely important strategy for insertion of proteins that are synthesized in the matrix!

- TOM

- TIM23

- OXA

- signal sequence

- signal sequence

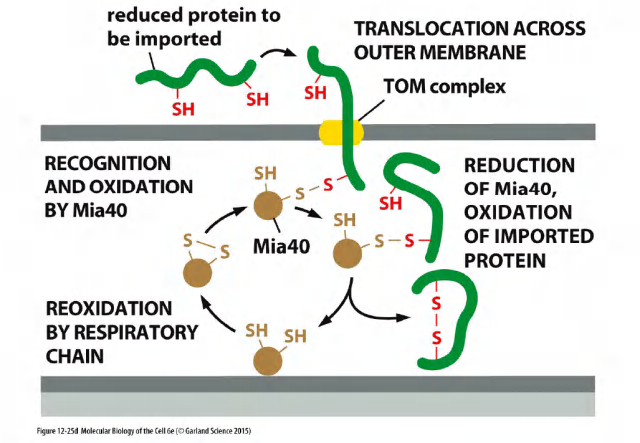

(5) Protein import into the inter membrane space (IMS)

Import of soluble proteins

TOM

TIM23

IM-localizing protease/peptidase

Targeting of soluble protein to the IMS via TOM & folding in the IMS by Mia40

Certain intermembrane-space proteins that contain cysteine motifs are imported by a yet different route.

These proteins form a transient covalent disulfide bond to the Mia40 protein

The imported proteins are then released in an oxidized form containing intrachain disulfide bonds. Mia40 becomes reduced in the process, and is then reoxidized by passing electrons to the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane.

TOM

Mia40 (Mia40: Mitochondrial IMS assembly machinery )

Mia40 forms a covalent intermediate through an intermolecular disulfide bond, which helps folding/pulling of the transported protein through the TOM complex.

Mia40 is reduced in the process, and is then reoxidized by the electron transport chain.

Summary: Protein import into the inner membrane (IM) and the intermembrane space (IMS) of mitochondria

Summary: Protein import into mitochondria

Mitochondrial proteins that are encoded by nuclear genes possess mitochondrial import sequences.

Transport from the cytosol into the mitochondria is mediated by a TOM complex and two TIM complexes.

The SAM complex mediates proper folding of outer membrane proteins with β-barrel structures.

Another complex (OXA) mediates insertion of mitochondrial-gene encoded proteins into inner membrane & also contributes to insertion of some nuclear-gene encoded proteins.

Proteins must be unfolded, either by chaperones or by specialized unfolding proteins.

2. Protein localization in plastids

Protein transport into chloroplasts resembles transport into mitochondria.

Both processes occur post-translationally, use separate translocation complexes in each membrane, require energy, and use amphiphilic N-terminal signal sequences that are removed after use.

Chloroplasts have three independent reaction rooms:

- IMS (intermembrane space)

- Stroma

- Thylakoids

Targeting to chloroplasts includes targeting to:

- OM: Outer Membrane

- IMS: Intermembrane Space

- IM: Inner membrane

- Stroma

- TM: Thylakoid membrane

- thylakoid lumen

Plastid localization signal

Features

Chloroplast precursor proteins are fully synthesized in the cytosol before their import.

Chaperones keep the proteins in an unfolded “import-competent” state and guide them to the TOC complexes, their import is referred to as “transmembrane transport”.

An N-terminal peptide directs many precursor proteins to matrix, then, this signal peptide it is cleaved upon arrival.

An internal peptide directs all precursor proteins into the outer membrane, many to be in the inner membrane and intermembrane (thylakoids).

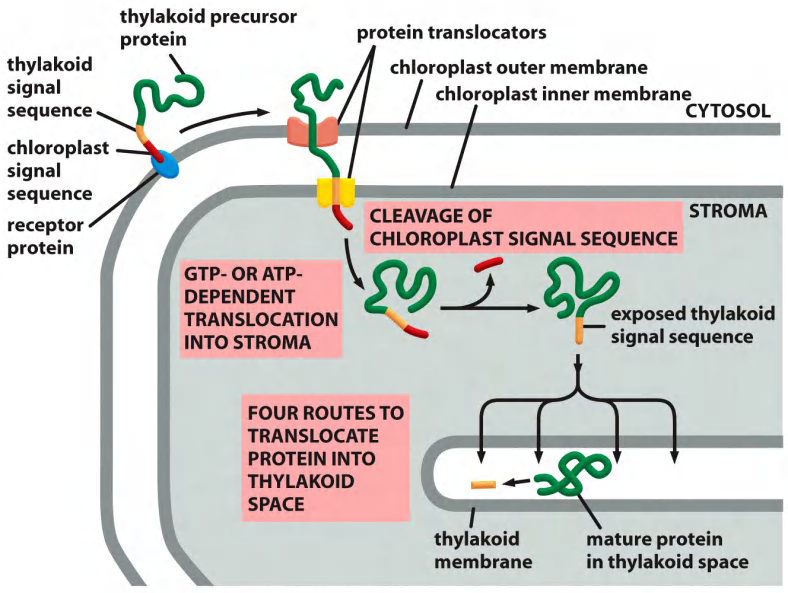

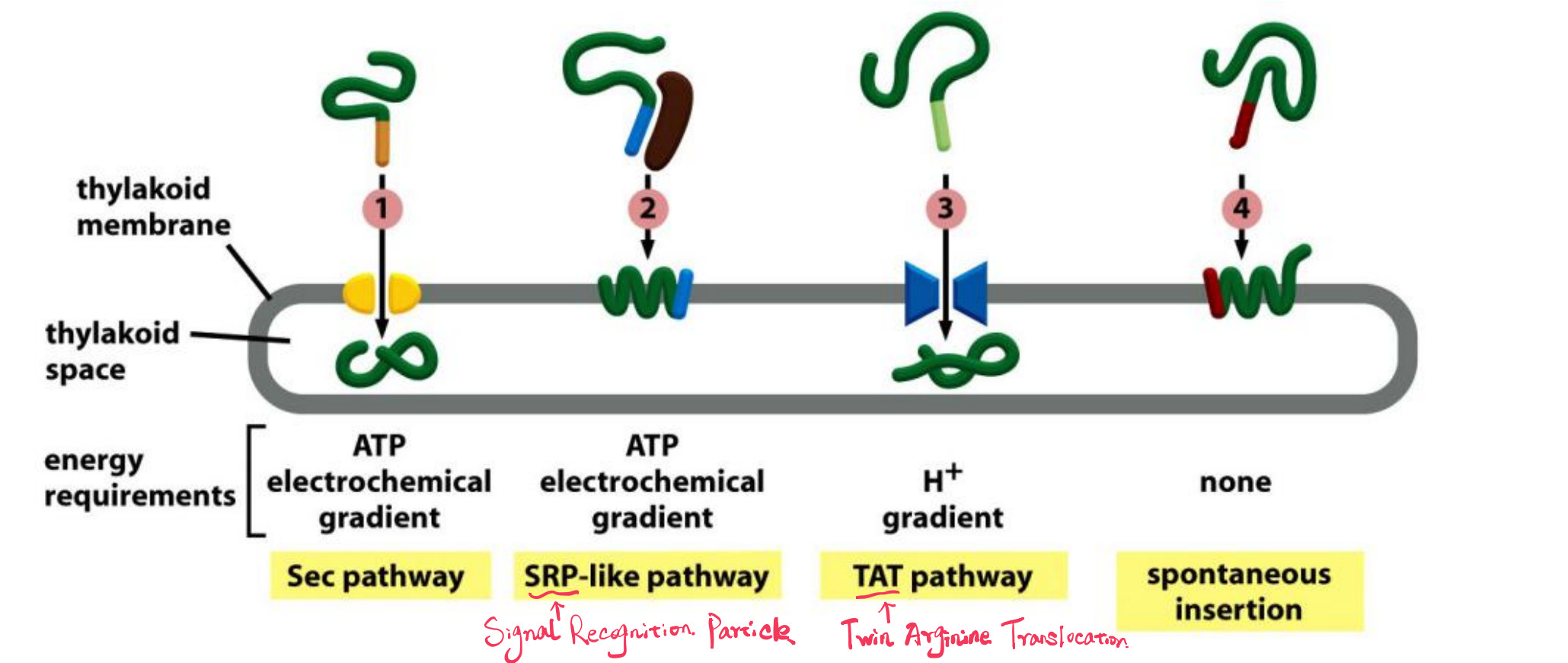

Translocation of chloroplast precursor proteins into the thylakoid lumen

Translocation into the thylakoid lumen or thylakoid membrane

- Sec pathway, so called because it uses components that are homologs of Sec proteins which mediate protein translocation across the bacterial plasma membrane

- SRP (Signal Recognition Particle)-like pathway, so called because it uses a chloroplast homolog of the signal-recognition particle (SRP)

- TAT (twin arginine translocation) pathway, so called because two arginines are critical in the signal sequences that direct proteins into this pathway, which depends on the H+ gradient across the thylakoid membrane

- Spontaneous insertion pathway that seems not to require any protein translocator

Summary: Protein import into chloroplast

Chloroplasts have 2 further targets for proteins:

- Thylakoid membrane

- Thylakoid lumen

- $\rarr$Two signal peptides direct proteins to the thylakoids (For signal peptide is cleaved after traanslocation):

- the first to reach the stroma

- the second to reach the thylakoids (thylakoid-specific).

Import receptors are chloroplast–specific:

- TOC: Translocase outer membrane chloroplast

- TIC: Translocase inner membrane chloroplast

- $\rarr$ some chloroplast-specific signal peptides & signals

Import is NOT driven by electrochemical energy, and is driven by ATP and GTP hydrolysis.

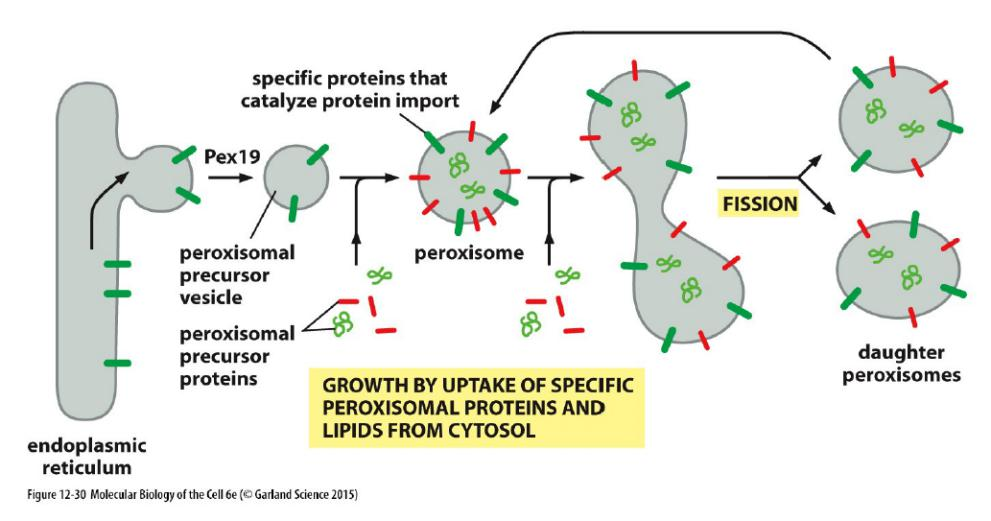

3. Transport to peroxisomes

Features

- Proteins with appropriate signal sequence squeeze through protein translocators

Function of Peroxisomes

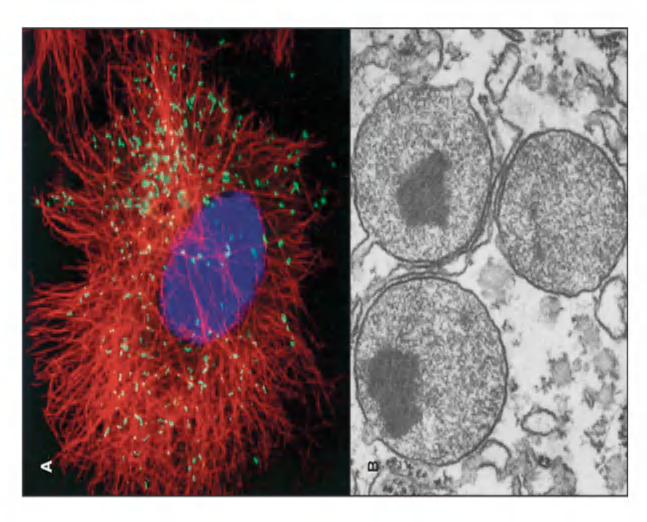

Virtually all eukaryotic cells have peroxisomes.

They contain oxidative enzymes, such as catalase (过氧化氢酶) and urate oxidase (尿酸氧化酶), at such high concentrations that, in some cells, the peroxisomes stand out in electron micrographs because of the presence of a crystalloid protein core

Peroxisomes detoxify chemicals, metabolize fatty acids and synthesize key lipid

Peroxisomes are so named because they usually contain one or more enzymes that use molecular oxygen to remove hydrogen atoms from specific organic substrates (designated here as R) in an oxidation reaction that produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): $RH_2 + O_2 → R + H_2O_2$

(TEM image of peroxisomes in a liver cell from a rat with paracrystalline, electron dense inclusions (enzyme urate oxidase))

Peroxisome plays several vital functions:

Contain catalase and oxidase

- Catalase use H2O2 to oxidize a variety of substrates by the “peroxidation” reaction : $H_2O_2 + R′ H_2 → R′ + 2H_2O$

- Remove excess H2O2 by : $2H_2O_2 → O_2 + 2H_2O$

Oxidize fatty acid by β-oxidation, producing acetyl-CoA

A major function of the oxidation reactions performed in peroxisomes is the breakdown of fatty acid molecules. The process, called β oxidation

- β oxidation shortens the alkyl chains (烷基链) of fatty acids sequentially in blocks of two carbon atoms at a time, thereby converting the fatty acids to acetyl CoA

In mammalian cells, β oxidation occurs in both mitochondria and peroxisomes;

in yeast and plant cells, however, this essential reaction occurs exclusively in peroxisomes.

Metabolize many harmful molecules

- Phenols 酚类

- Formaldehyde 甲醛

- Alcohol

It is particularly important in liver and kidney cells, where peroxisomes detoxify various toxic molecules that enter the bloodstream.

∼ 25% of the ethanol we drink is oxidized to acetaldehyde in this way!

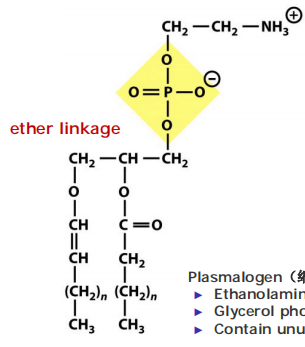

(1) Peroxisomes are important for the synthesis of plasmalogen 缩醛磷脂

An essential biosynthetic function of animal peroxisomes is to catalyze the first reactions in the formation of plasmalogens, which are the most abundant class of phospholipids in b

- Plasmalogen deficiencies cause profound abnormalities in the myelination of nerve-cell axons, which is one reason why many peroxisomal disorders lead to neurological disease.

peroxisomes catalyze the initial step in the synthesis of a special lipid called plasmalogen.

Plasmalogen localizes to the cell membrane of cells that form myelin sheaths around axons.

Important substance for myelin sheath to protect/insulate axons of nerve cells.

Plasmalogen(缩醛磷脂):

- Ethanolamine head group

- Glycerol phosphate backbone with attached long-chain fatty acid

- Contain unusual fatty alcohol that is attached via an ether linkage(醚键)

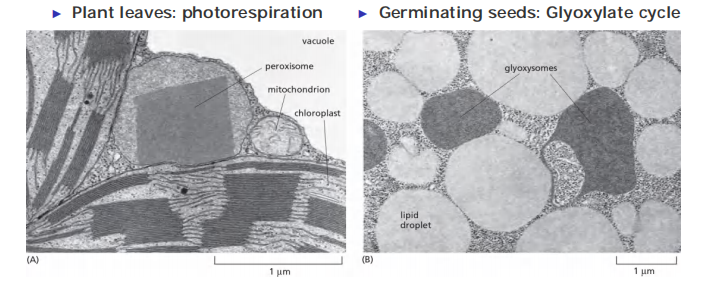

(2) Peroxisomes in plant cells carry out unique functions

Peroxisomes are also important in plants. Two types of plant peroxisomes have been studied extensively.

- One is present in leaves, where it participates in photorespiration

- The other type of peroxisome is present in germinating seeds, where it converts the fatty acids stored in seed lipids into the sugars needed for the growth of the young plant

Because this conversion of fats to sugars is accomplished by a series of reactions known as the glyoxylate cycle (乙醛酸循环), these peroxisomes are also called glyoxysomes

Peroxisome: in plant leaves close association with chloroplasts to facilitate the exchange of materials between these organelles during photorespiration (for details about photorespiration, see lecture 14).

Glyoxysome (乙醛酸循环体) : in germinating cells association with the lipid droplets that store fat.

Proteins inserted post-translationally into peroxisomes

Features

- Require a signal sequence recognized by another set of proteins in the peroxisome membrane which form a channel through with peroxisomal proteins enter a peroxisome.

The proteins that target proteins to peroxisomes and form the channel are called Pex proteins.

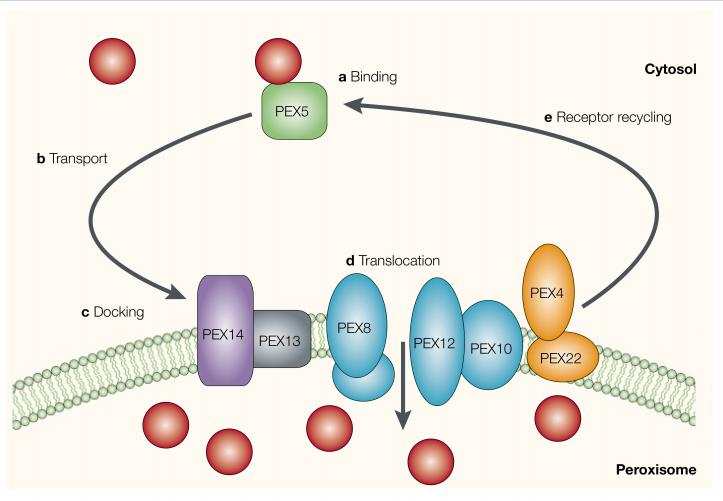

(1) Proteins transport into peroxisomes

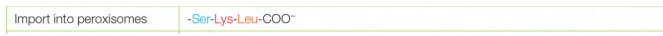

Short C-terminal signal peptide (Ser–Lys–Leu) directs protein import into peroxisome

A specific sequence of three amino acids (Ser–Lys–Leu) located at the C-terminus of many peroxisomal proteins functions as an import signal

Numerous distinct proteins, called peroxins, participate in the import process, which is driven by ATP hydrolysis. A complex of at least six different peroxins forms a protein translocator in the peroxisome membrane.

Cytosolic receptor protein recognize signal sequence.

Several peroxins dock on cytosolic surface as a membrane translocator

Import requires ATP.

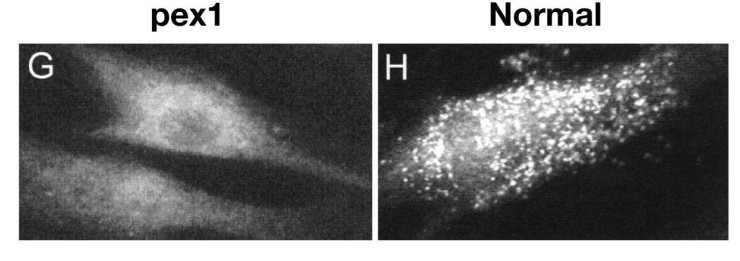

Mutations in Pex proteins lead to loss of peroxisomes

One soluble import receptor, the peroxin Pex5 recognizes the C-terminal peroxisomal import signal. It accompanies its cargo all the way into peroxisomes and, after cargo release, cycles back to the cytosol

- After delivering its cargo to the peroxisome lumen, Pex5 undergoes ubiquitylation.

- This modification is required to release Pex5 back into the cytosol, where the ubiquitin is removed. An ATPase composed of Pex1 and Pex6 harnesses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to help release Pex5 from peroxisomes.

A defect in Pex7, the receptor for the N-terminal import signal, causes a milder peroxisomal disease.

Pex mutations cause Zelleweger Syndrome and demyelination of nerves

Zelleweger Syndrome

- Disease is named after Hans Zellweger (1909–1990), a Swiss-American pediatrician

- inherited genetic disease due to mutation in peroxin Pex5

- The mutation affects protein import in peroxisomes and the biogenesis of peroxisomes

- severe abnormality in brain, liver and kidney development

- rarely survives till 6-month old