L13 Organelles

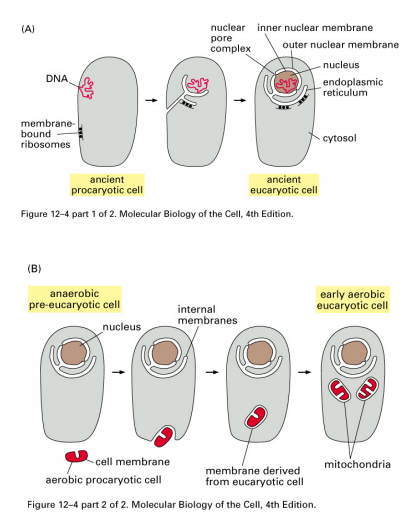

The Origin of Eukaryotic Organelles

A vast body of evidence from molecular and cell biology supports the endosymbiont hypothesis of organelle origin.

Plastids and mitochondria evolved from separate endosymbiotic events in which the endosymbionts became highly specialized to perform the processes of photosynthesis and respiration, respectively.

一、Organelles

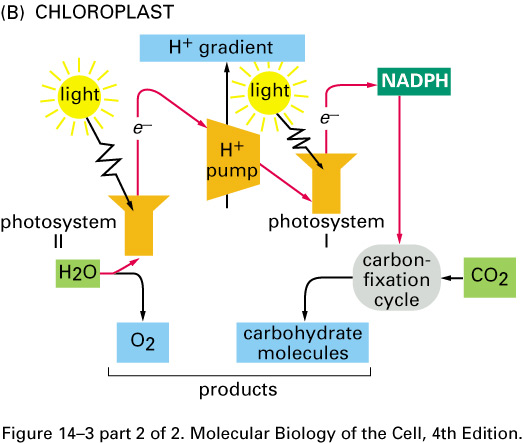

Chloroplast Function

Chloroplast Function: Havesting energy (ATP) from light

The chloroplast is the chlorophyll-containing organelle that carries out photosynthesis and starch-grain formation in plants.

Chloroplasts are referred to as plastids before chlorophyll develops

二、Organelle Gene

Plant Plastid

1. Plastid 色素体

色素体(英语:plastid),又称质粒体或质体,是植物、藻类、光合营性细菌中所含有的一种囊泡,与光合作用有关。囊泡中含有菌绿素与类胡萝卜素。在紫细菌中,如紫螺菌,色素体的膜上天生就拥有捕光蛋白。而绿硫菌的色素体则拥有一种特殊的天线复合体,这种色素体被称为绿色体。

2. Plant Plastid Genome

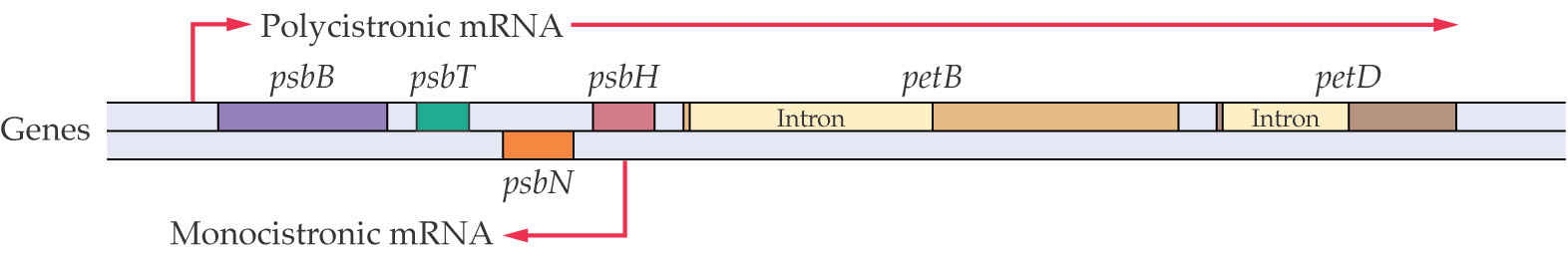

Plant plastid genomes are typically organized into operons similar to those of prokaryotes. This is a “polycistronic” transcriptional unit in which clusters of two or more genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase from a single promoter.

Some of these polycistronic transcripts encode functionally distinct proteins. Often, the mRNA will be produced, but not the protein for one or more of the genes in the operon. This indicates that post-transcriptional regulation is important.

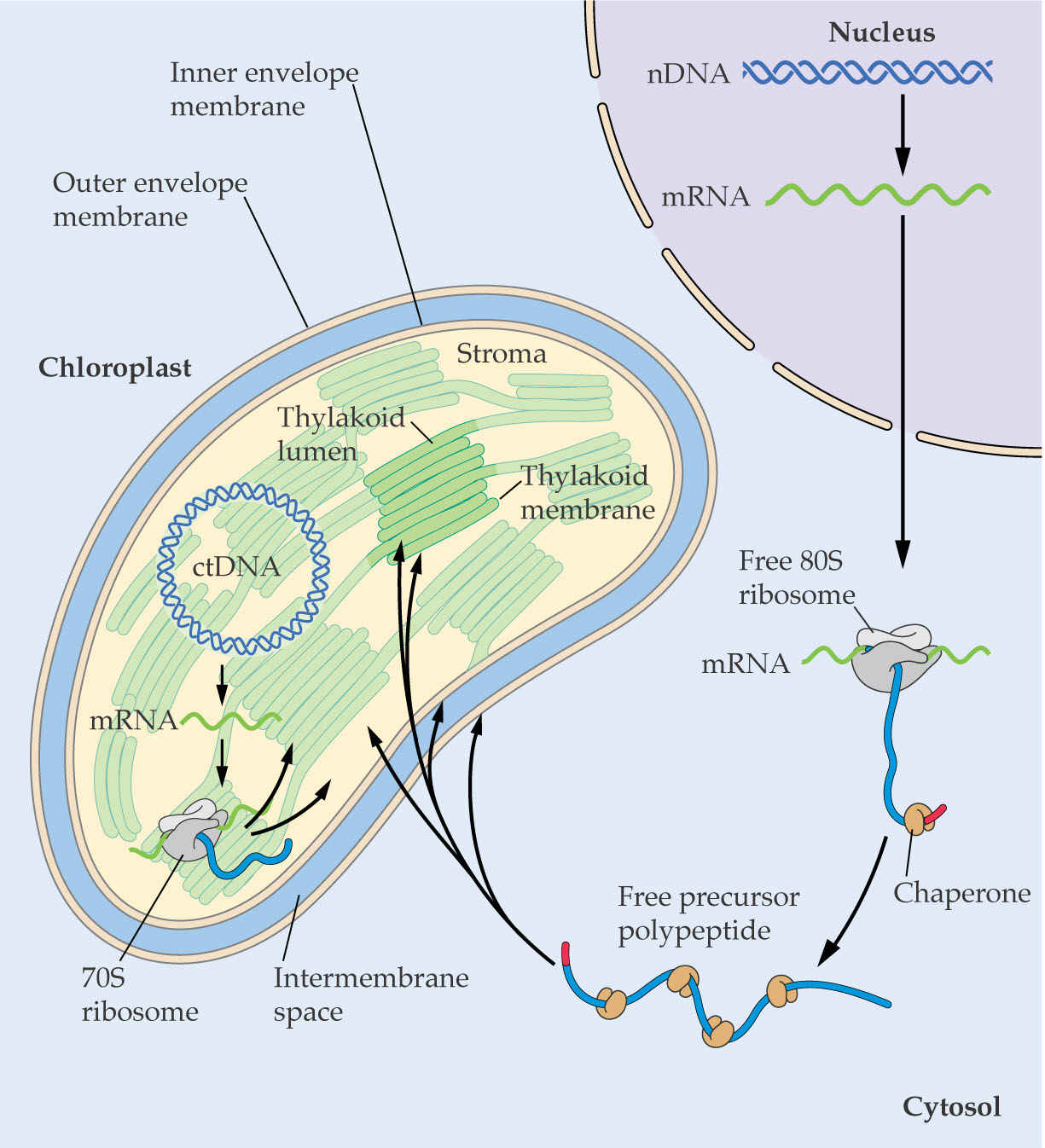

3. Biosynthesis of Plastid Proteins

Chloroplast proteins may be encoded in the nucleus or in the chloroplast.

Translation of the mRNAs is performed by different ribosomes, the 80S in the cytoplasm for nuclear transcripts, or 70S ribosomes for chloroplast encoded-mRNAs.

Proteins made in the cytoplasm may be targeted to the chloroplast.

3. Multiple RNA Pol Function in Plastid Genomes

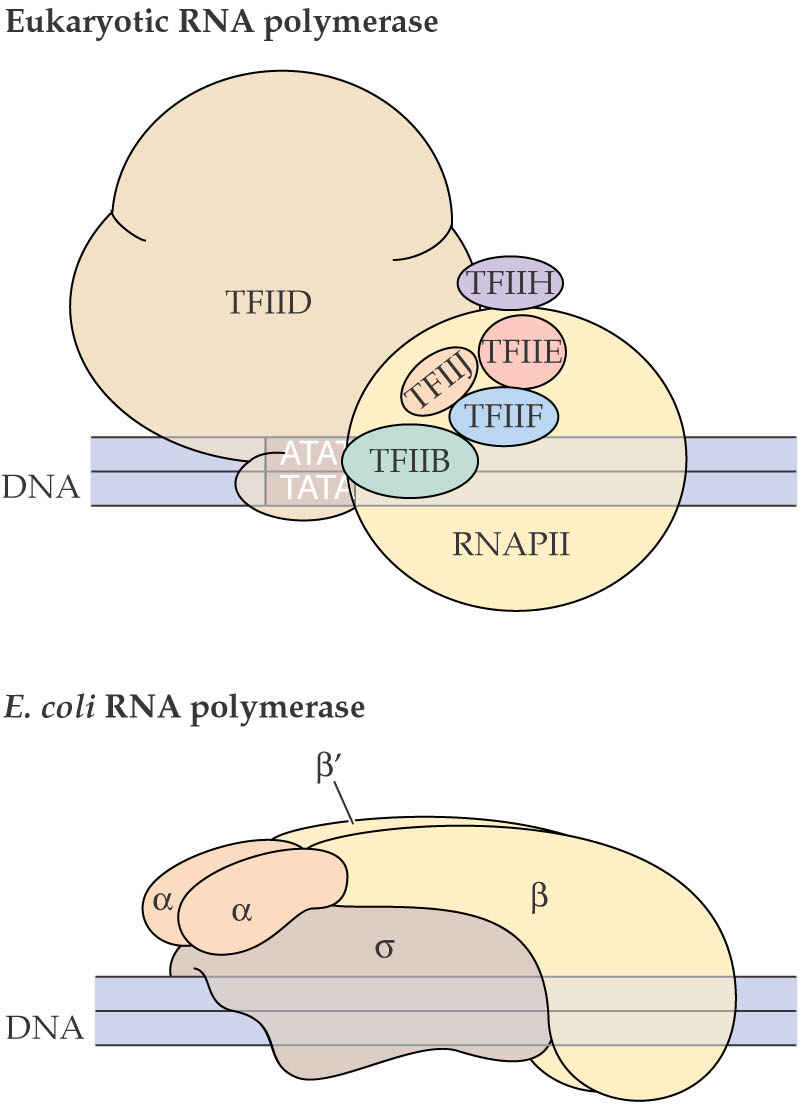

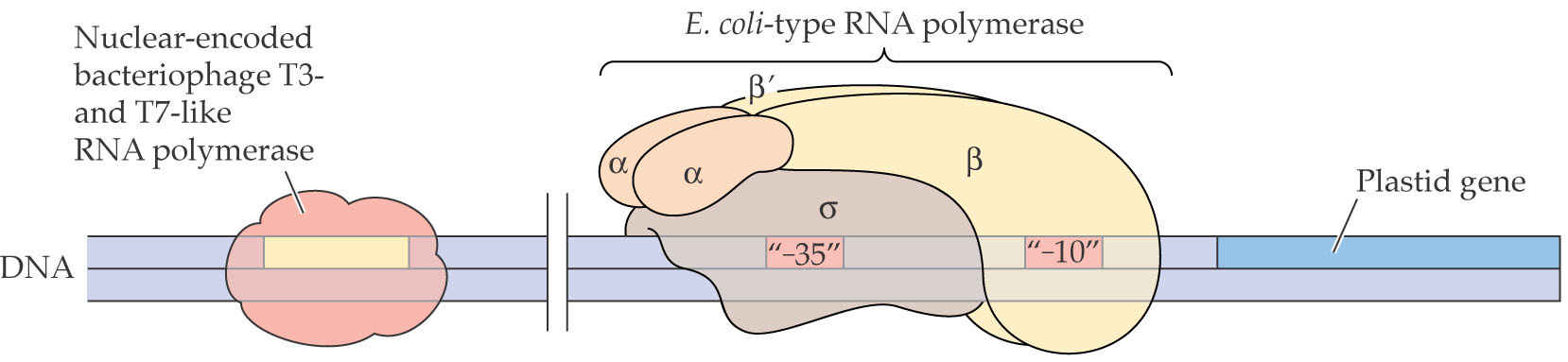

Plant chloroplasts have two types of RNApolymerases. Plastid genes encode proteins similar to E. coli RNA polymerase, suggesting the presence of a prokaryotic-type chloroplast RNA polymerase. Genes for similar subunits have been identified in the nuclear genomes of many plants, indicating that both plastid and nuclear genomes cooperate in the regulation of chloroplast transcription.

The plastid-encoded RNA polymerase recognizes chloroplast promoters that contain typical “-10” and “-35” prokaryotic consensus sequences.

When specific inhibitors of translation are used to block translation in the chloroplast, the nuclear-encoded RNA polymerase activity continues to transcribe chloroplast genes.

4. Prokaryotic Attributes of Plastid Genomes

A prokaryotic-like chloroplast RNA polymerase recognizes chloroplast promoters thatcontain “-10” and “-35” consensus sequences typical of prokaryotes.

A prokaryotic-like chloroplast RNA polymerase recognizes chloroplast promoters that contain “-10” and “-35” consensus sequences typical of prokaryotes.

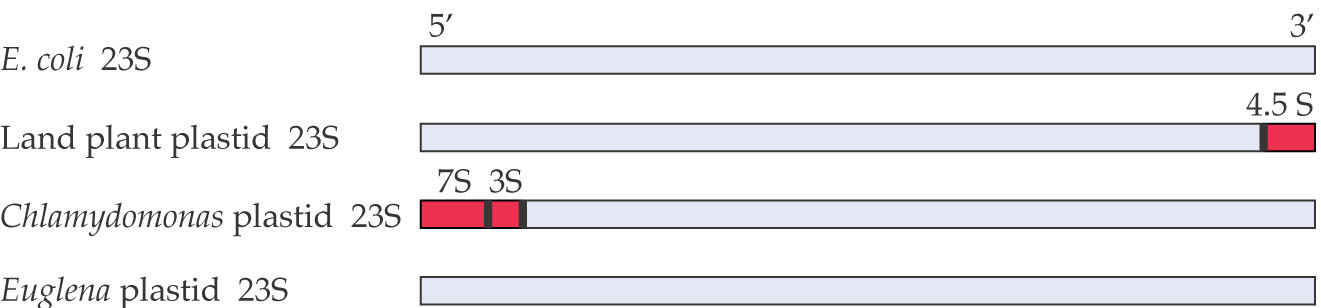

A comparison of plastid 23S ribosomal RNA sequences shows that the plant plastid-encoded 23S rRNAs are quite similar to that of E. coli.

Regulation of Gene Expression in Plastids

Chloroplast promoters: Transcription in some ways resembles that of prokaryotes.

Transcripts usually polycistronic

Promoter regions are homologous

Terminators homologous to prokaryotic terminators

E. coli RNA polymerase can initiate accurate transcription of ct genes in vivo and in vitro

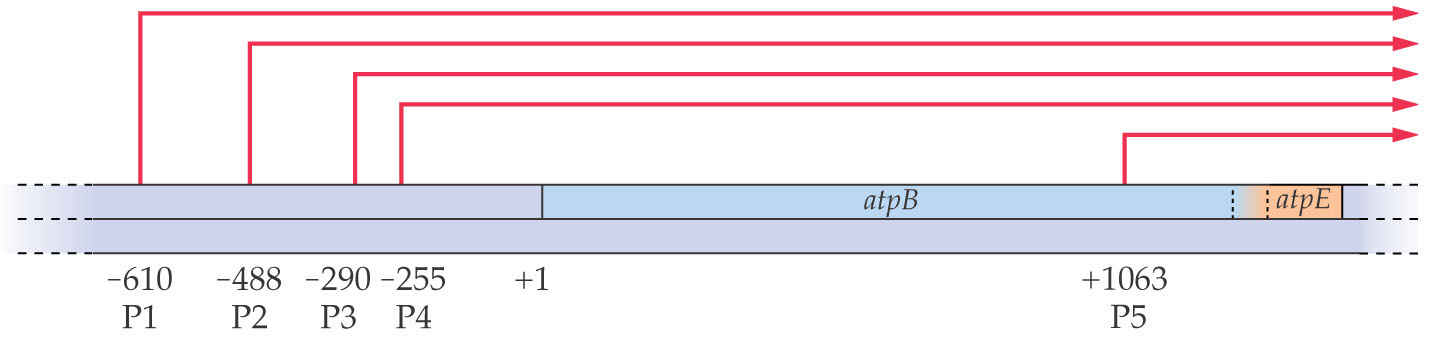

Multiple promoters direct transcription of the atpB-atpE gene cluster in tobacco chloroplasts. There are five transcriptional initiation sites indicated by red arrows, four of which have the -10 and -35 consensus sequences. Use of several promoters allows fine-tuning of transcriptional regulation. (Nuclear genes typically have one promoter.)

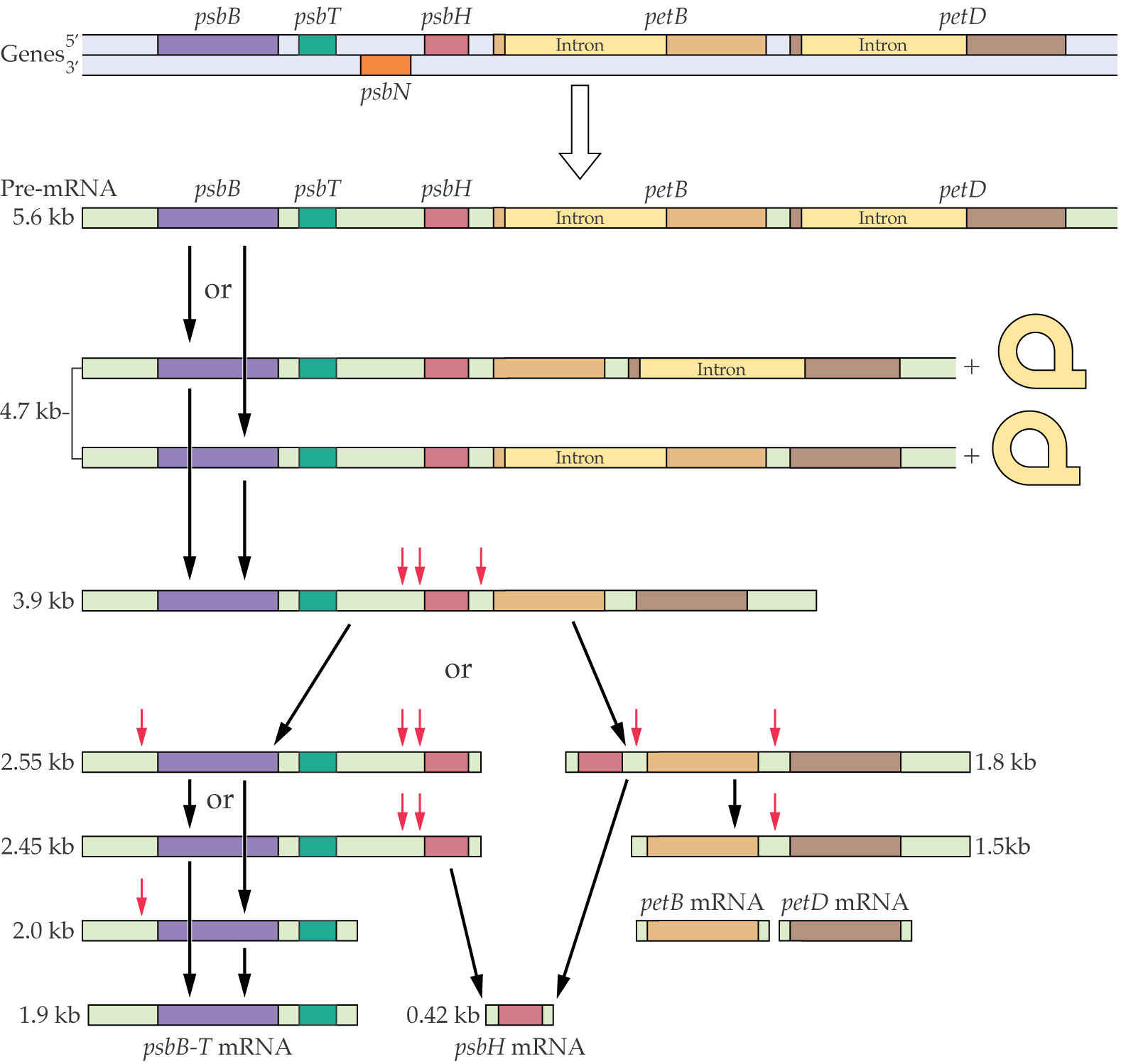

5. Processing of Polycistronic (多顺反子) Plastid RNAs

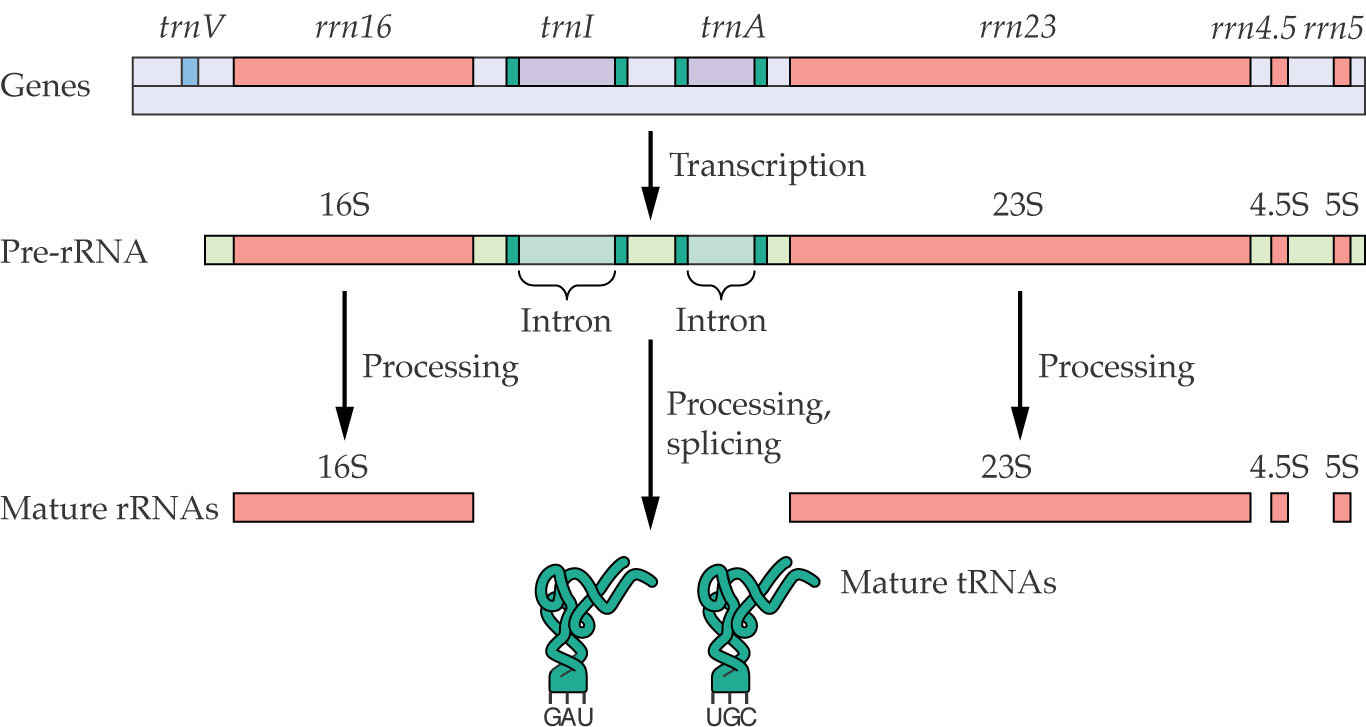

Chloroplast pre-RNAs molecules are processed. Unlike the nuclear-encoded rRNA molecules, the chloroplast rRNA operon also encodes two tRNAs in the spacer regions that separate the 16S and 23S rRNA. The tRNAs contain introns, and the entire pre-mRNA is processed to form separate RNA molecules.

The transcript from the psbB operon in plant plastids is a typical example of the complex processing and splicing reactions that are required to cleave the polycistronic mRNA precursor into mature monocistronic mRNAs that can be translated into proteins.

Land plant chloroplast genomes contain ∼20 group II introns and a single group I intron.

Group I introns are large self-splicing ribozymes.

Group II catalytic introns are found in rRNA, tRNA, and mRNA of organelles

- (chloroplasts and mitochondria) in fungi, plants, and protists, and also in mRNA in bacteria. They are large self-splicing ribozymes and have 6 structural domains.

These introns are derivatives of self-splicing ribozymes that have become dependent upon proteins for their splicing.

The Chloroplast Genome

1. Introduction

Chloroplasts contain multiple copies of a circular genome and ribosomes that synthesize organelle-encoded proteins.

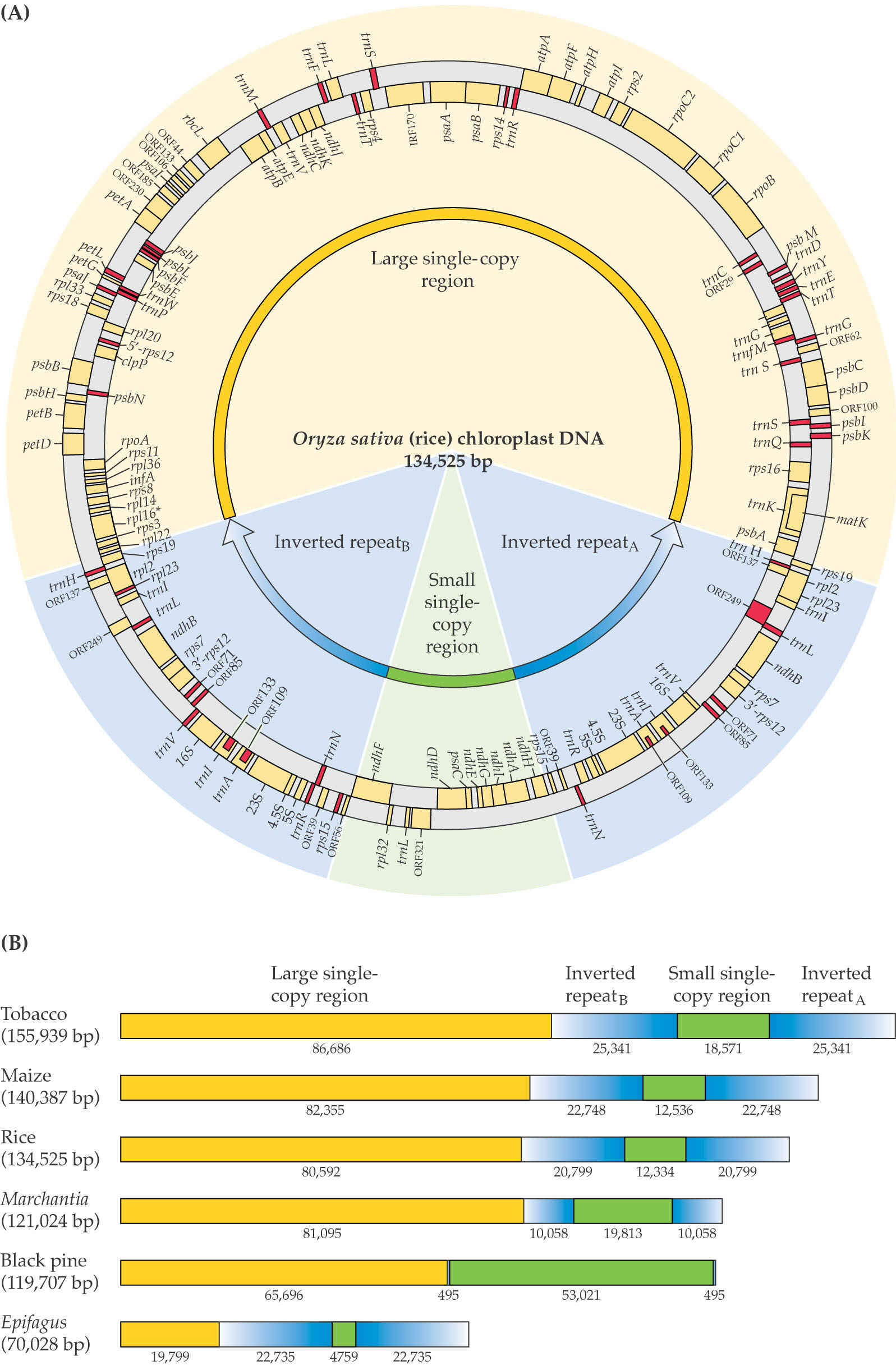

The chloroplast genome is circular and 120,000 to 160,000 bp depending on the species.

It includes ~120 genes, of which ~60 are involved in transcription and translation.

About 20 genes are involved in photosynthesis.

The RNA polymerases and ribosomal proteins are similar to those of bacteria.

Comparisons across plant species show variation: some proteins are encoded in the chloroplast or the nucleus. But all chloroplasts contain similar sets of proteins. Therefore, some exchange of genes occurs between the chloroplast and nucleus.

2. Organization

Plant chloroplast genomes have a typical structure that includes a small and a large single copy region that is separated by two inverted repeats. The length of the inverted repeat varies widely among different plant species.

Origins of replication are located in the long inverted repeats (blue).

3. Model For Replication of Chloroplast Genome

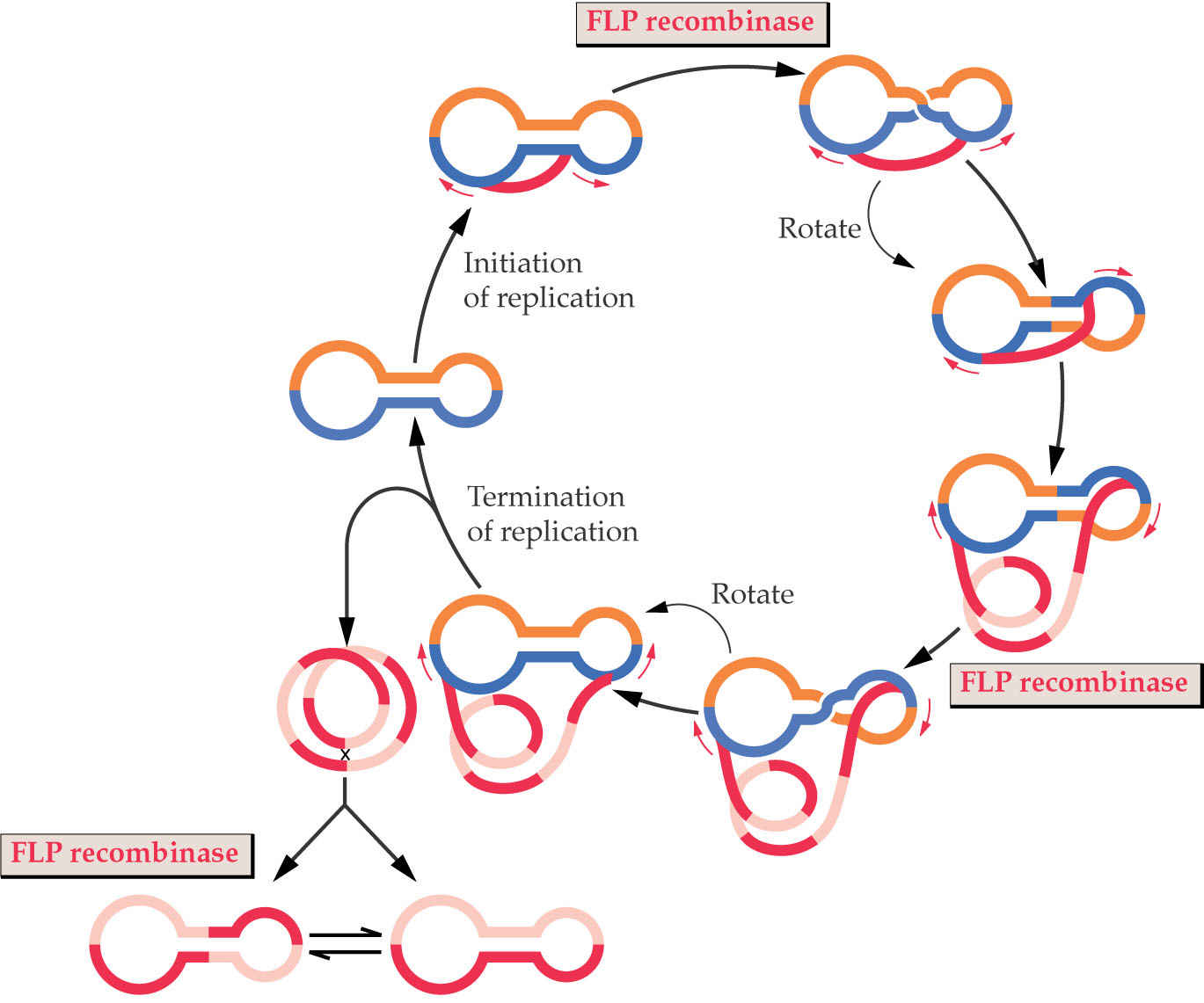

Each chloroplast contains many copies of the chloroplast genome (~150?), but this copy number can vary with the developmental stage, light, etc.

High copy number may result from need for large amount of proteins involved in photosynthesis.

Replication is proposed to take place via a “double rolling-circle mechanism”. The key point of this mechanism is that it generates long concatameric DNA fragments: many copies of the same DNA attached in a linear order. Monomeric genomes can be processed out of this concatameric molecule by recombination.

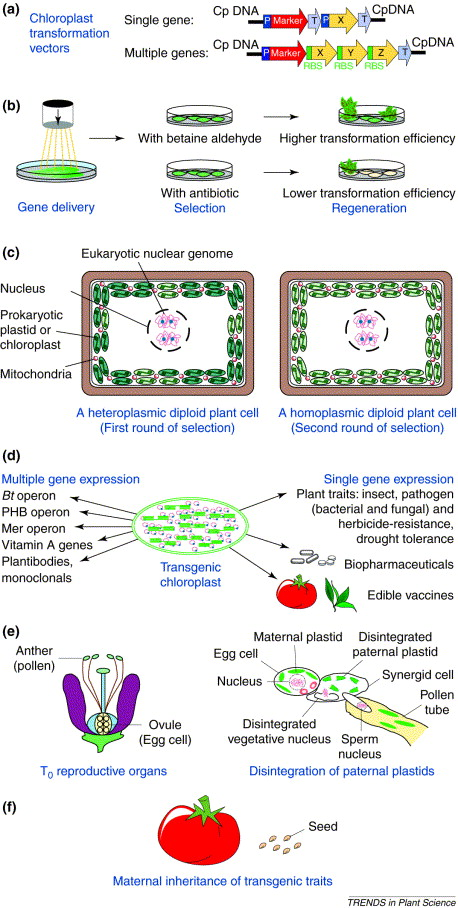

4. Engineering of Chloroplast Genome

The genetic transformation of organelle genomes requires converting the entire set of organelle genomes within a cell to the transformed genotype (= homoplasmy). Initially, only one or a few of the DNA molecules within the plastid will be transformed, so the plant cell will be heteroplasmic.

Biolistic transformation of plastids is usual (the gene gun).

The most common selection system for plastid transformation is spectinomycin, a chemical that inhibits activity of bacterial ribosomes. Plastid ribosomes are much more susceptible to spectinomycin than are cytosolic ribosomes.

Transformed sectors are identified as those that are green under those conditions (due to plastid gene expression). Plants are regenerated from the green sectors.

In contrast to plant nuclear genome transformation, plastid transformation occurs by homologous recombination.

One advantage is the high copy of the chloroplast genome makes it easier to produce large quantities of a specific protein (like a pharmaceutical product).

Plastid genes do not undergo silencing often observed with nuclear transgenes.

Mitochondrial Genome

1. Introduction

At mitosis, each daughter cell receives approximately the same number of mitochondria.

Each mitochondria contains multiple copies of the genome.

Therefore, the amount of mtDNA per cell depends on the number of mitochondria, the number of genomes per mitochondria, and the size of the mitochondrial genome.

To date, plant mitochondrial genomes have not been successfully transformed. Selection is a particular challenge because these organelles are essential for life.

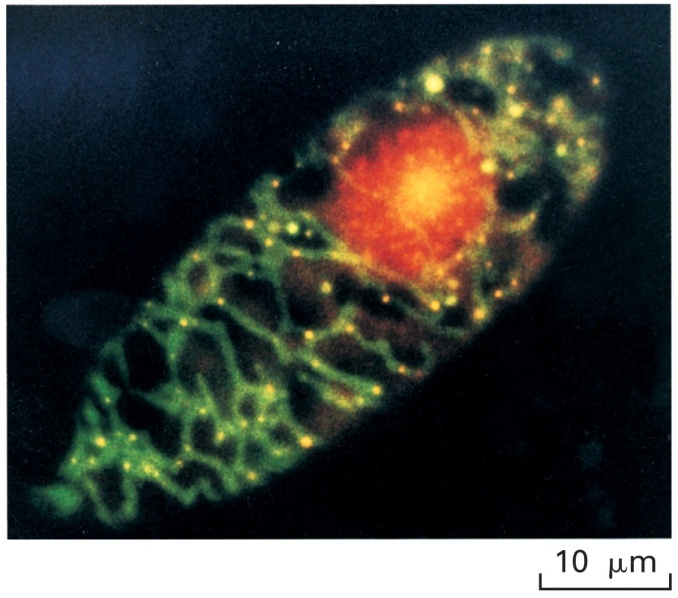

Cells contain multiple copies of the mtDNA. The yellow dots above mark the prescence of the mtDNA –at least 30 are visible in this cell.

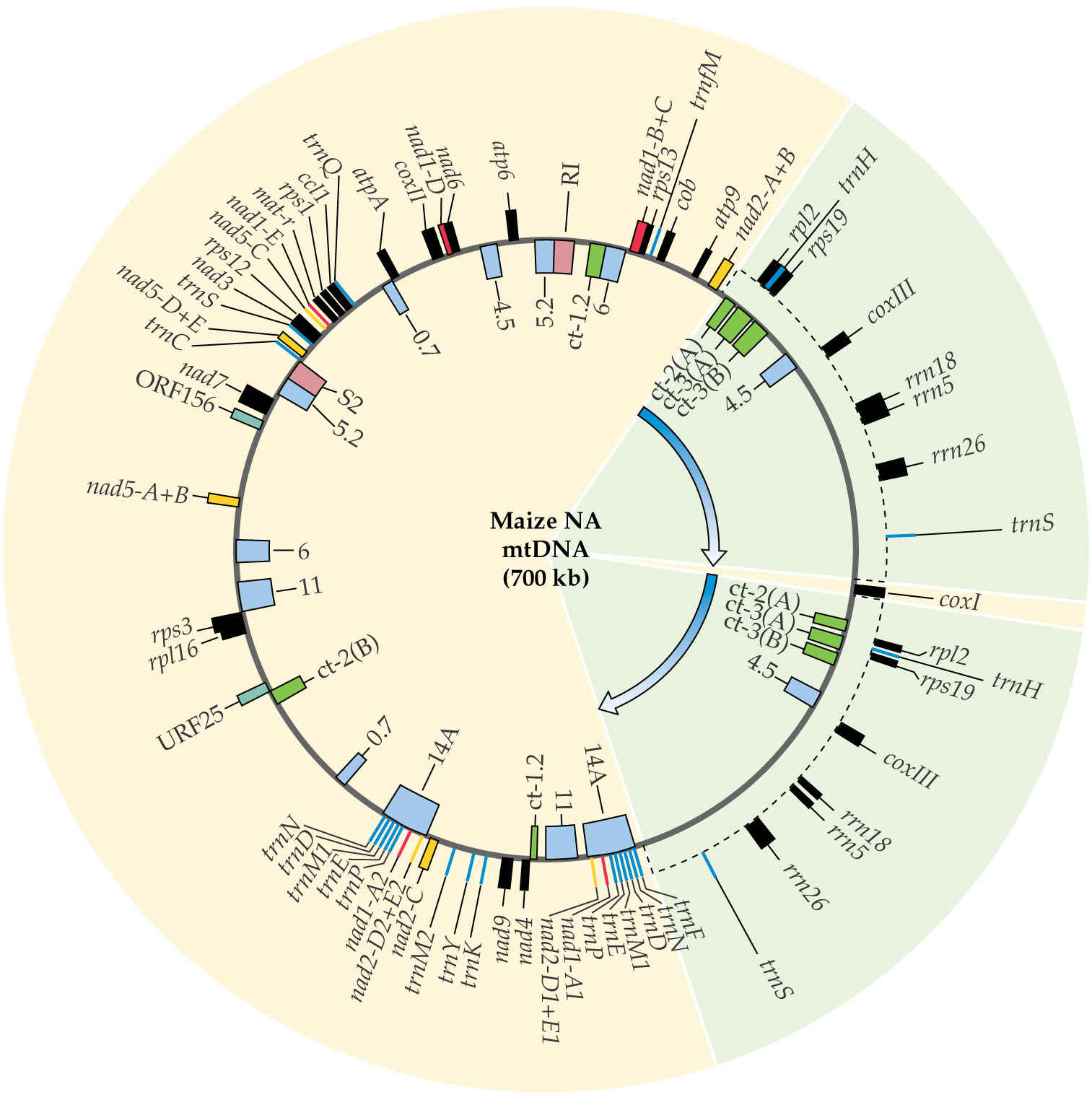

Plant mitochondrial genomes vary from 200 kb to 2600 kb and are thus highly variable. This is the result of the accumulation of an unusually large amount of non-coding RNA between genes. This is non-repetitive sequence (compare to nuclear genome!).

In Arabidopsis, coding regions make up less than 10% of the 367 kb genome.

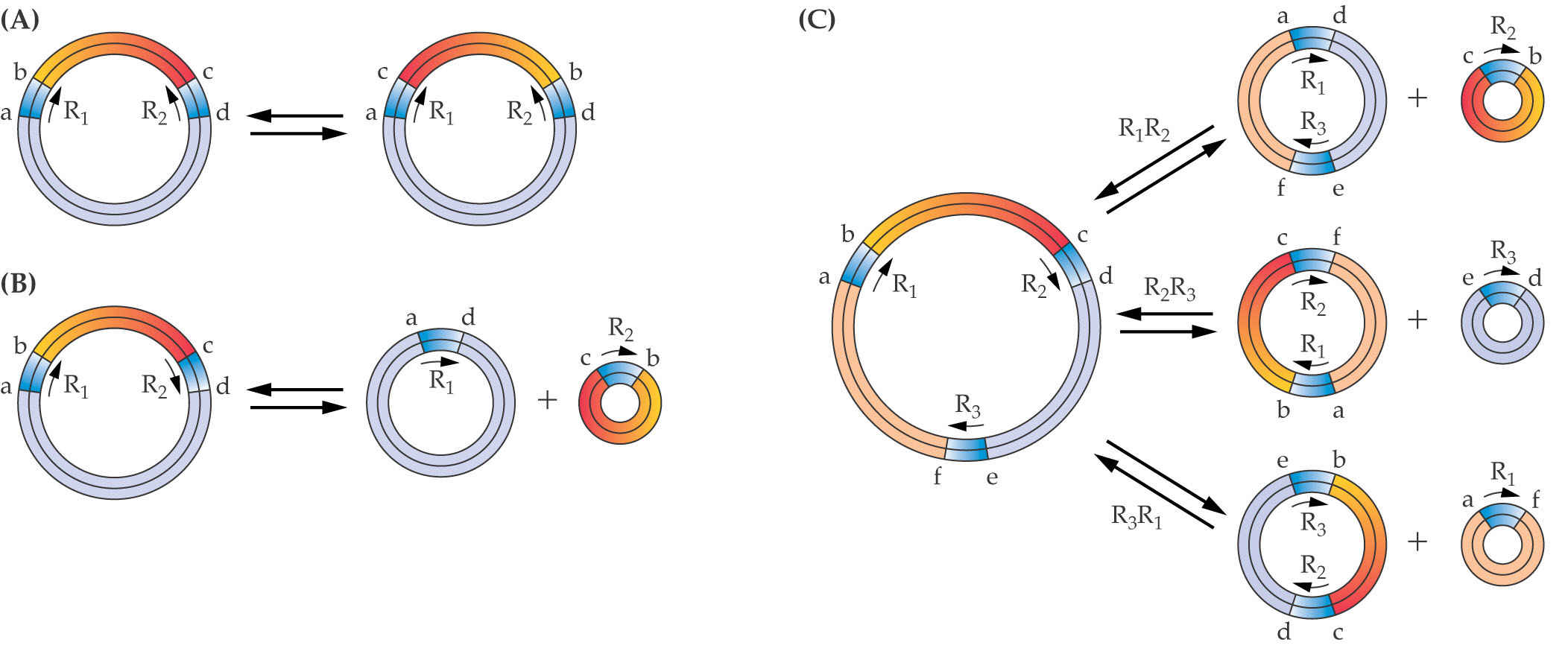

The genome at right from maize is hypothetical, because repeated sequences recombine to produce subgenomic circles.

2. Subgenomic Circles

Subgenomic circles : A fragmented mitochondrial genome due to homologous recombination

Plant mitochondrial genomes often exist as variably sized DNA circles. The combined DNA content of the smaller circles accounts for the entire mitochondrial genome. These subgenomic circles likely result from frequent homologous recombination events that break apart the master circle.

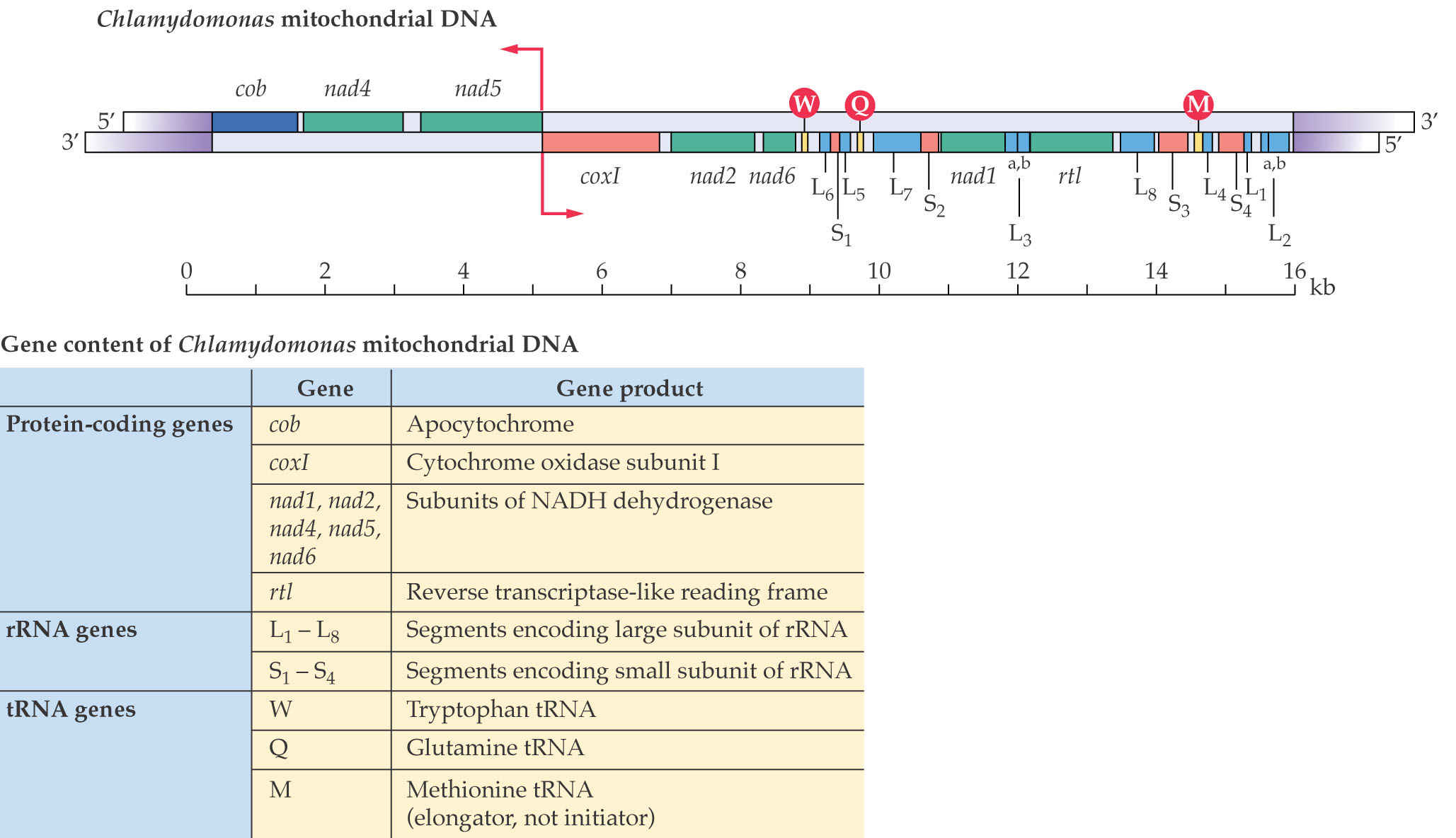

3. Chlamydomonas Mitochondria Genome

This is an unusual linear genome that apparently does not form the subgenomic circles; the genetic information is essentially the same.

Most of the genes in the mitochondrial genome participate in oxidative respiration, ATP synthesis or mitochondrial translation. Enzymes required for DNA replication, transcription and translation are encoded in the nuclear genome.

4. Others

The arabidopsis nuclear genome also contains most of the mitochondrial genome

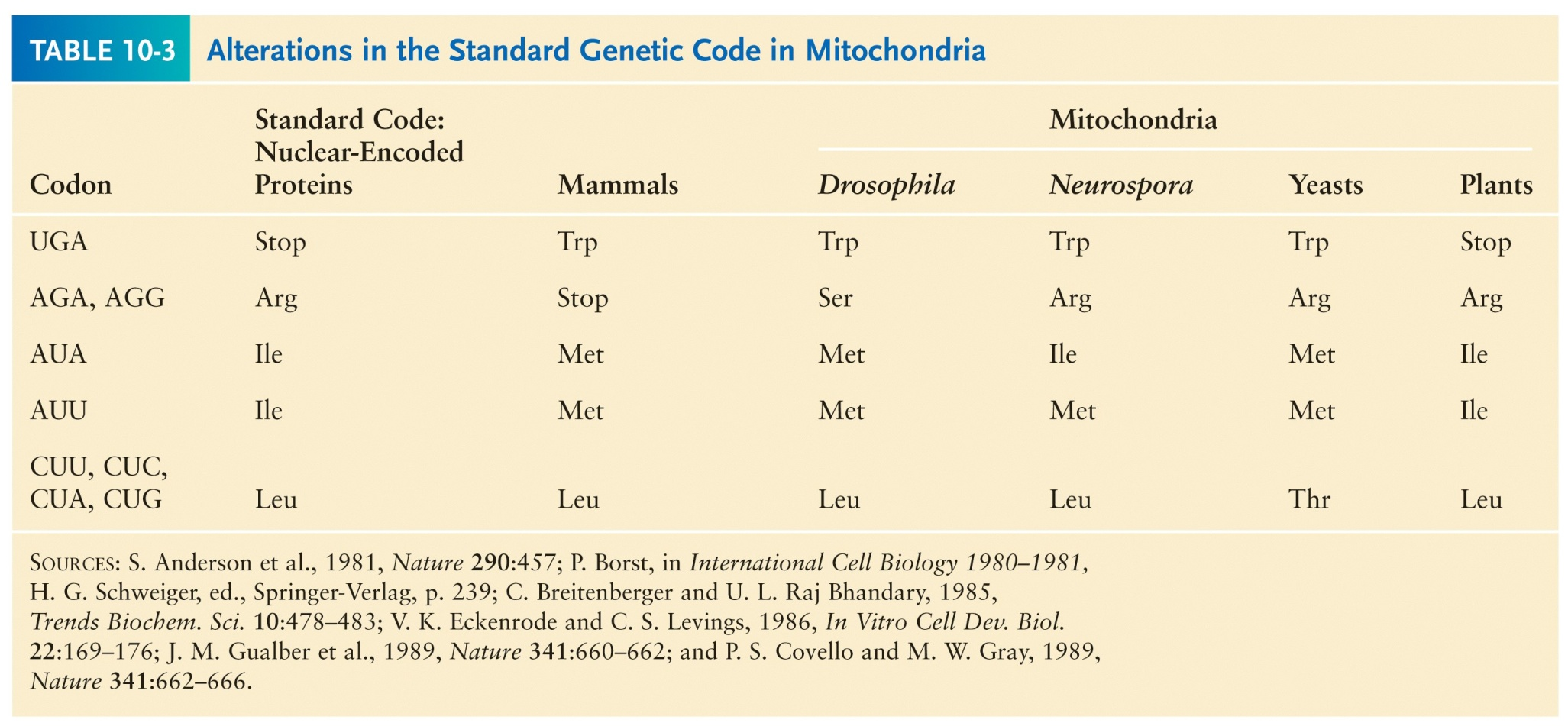

5. Mitochondroal Genetic Code

The mitochondrial genetic code is different from the standard genetic code. This code even differs between different species, but the reason for the differences is unknown.

Analysis of mitochondrial proteins indicated that CGG could code for either arganine (the standard amino acid for this codon) or tryptophan. This apparent non-specificity was highly unusual, and it turned out that editing of RNA transcripts was altering the CGG to UGG

Mitochondrial Genome VS. Chloroplast Genome

Mitochondrial Genome and Chloroplast Genome reveals extensive movement of DNA between genomes

Mitochondrial vs. chloroplast DNA from rice. The colored triangles and boxes shown on the rice chloroplast genome (inner circle) represent DNA sequences transferred to the mitochondria and inserted at different sites.

Note that mitochondrial DNA sequences have not been found in the chloroplast genome, suggesting that DNA transfer may be unidirectional or that the chloroplast may have an effective mechanism to protect itself against invading DNA molecules.

Organelle mRNAs

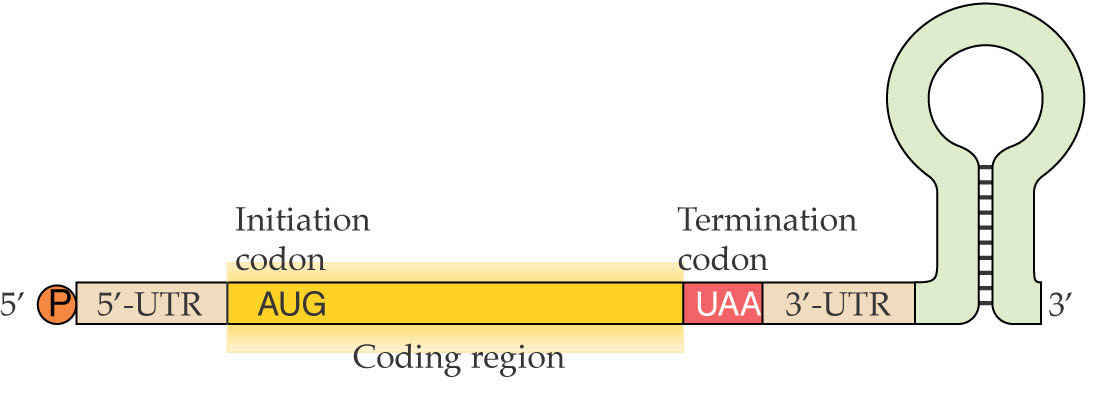

Organelle mRNAs are not polyadenylated (polyadenylated)

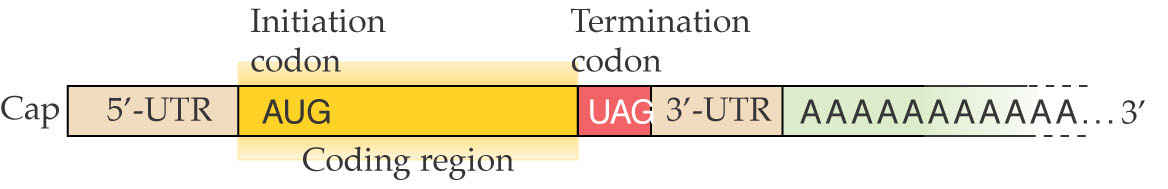

Structure of a mature nuclear-encoded plant mRNA, complete with cap, 5’UTR, translational start and termination, 3’UTR and poly(A) tail.

Structure of a typical mature chloroplast mRNA. Chloroplast mRNAs resemble prokaryotic mRNAs and are not modified at the 5’ end. The 3’ end has a stem-loop structure rather than a poly(A) tail, and this is important for RNA stability. In contrast to nuclear mRNAs, 3’ polyadenylation results in decay of plastid mRNA molecules.