L10 Learning and Memory

You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realise that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all…Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it, we are nothing…(I can only wait for the final amnesia, the one that can erase an entire life, as it did my mother’s…)

― Luis Bunuel

As many investigators have said, an understanding of the physiology of memory is the ultimate challenge to neuroscience research….

Objectives

- Describe each of four basic forms of learning: perceptual learning, stimulus–response learning, motor learning, and relational learning.

- Describe the anatomy of the hippocampus, describe the establishment of long-term potentiation, and discuss the role of NMDA receptors in this phenomenon.

- Discuss research on the physiological basis of synaptic plasticity during long-term potentiation and long-term depression.

- Describe research on the role of the inferior temporal cortex in visual perceptual learning.

- Discuss the physiology of the classically conditioned emotional response to aversive stimuli.

- Describe the role of the basal ganglia in instrumental conditioning.

- Describe the role of dopamine in reinforcing brain stimulation and discuss the effects of administering dopamine antagonists and agonists.

- Describe the nature of human anterograde amnesia and explain what it suggests about the organization of learning.

- Describe the role of the hippocampus in relational learning, including episodic and spatial learning, and discuss the function of hippocampal place cells.

一、The Nature of Learning

Learning refers to the process by which experiences change our nervous system and hence our behavior. We refer to these changes as memories.

Learning can take at least four basic forms:

- perceptual learning 知觉学习

- Learning to recognize a particular stimulus. 学习识别特定的刺激

- stimulus–response learning 刺激反应学习

- Learning to automatically make a particular response in the presence of a particular stimulus; includes classical and instrumental conditioning. 学习在特定反应条件下做出特定的刺激

- motor learning 运动学习

- Learning to make a new response. 学习做出新的反应

- relational learning 关联学习

- Learning the relationships among individual stimuli. 学习单个刺激之间的关系

Perceptual learning

Perceptual learning is the ability to learn to recognize stimuli that have been perceived before.

- The primary function of this type of learning is the ability to identify and categorize objects (including other members of our own species) and situations.

Unless we have learned to recognize something, we cannot learn how we should behave with respect to it—We will not profit from our experiences with it, and profiting from experience is what learning is all about.

- Each of our sensory systems is capable of perceptual learning. We can learn to recognize objects by their visual appearance, the sounds they make, how they feel, or how they smell.

- Perceptual learning appears to be accomplished primarily by changes in the sensory association cortex. i.e, learning to recognize complex visual stimuli involves changes in the visual association cortex, learning to recognize complex auditory stimuli involves changes in the auditory association cortex, etc.

Stimulus-response learning

Stimulus-response learning is the ability to learn to perform a particular behavior when a particular stimulus is present.

- It involves the establishment of connections between circuits involved in perception and those involved in movement.

- The behavior could be an automatic response such as a defensive reflex, or it could be a complicated sequence of movements.

- Stimulus–response learning includes two major categories of learning that psychologists have studied extensively: classical conditioning and instrumental conditioning.

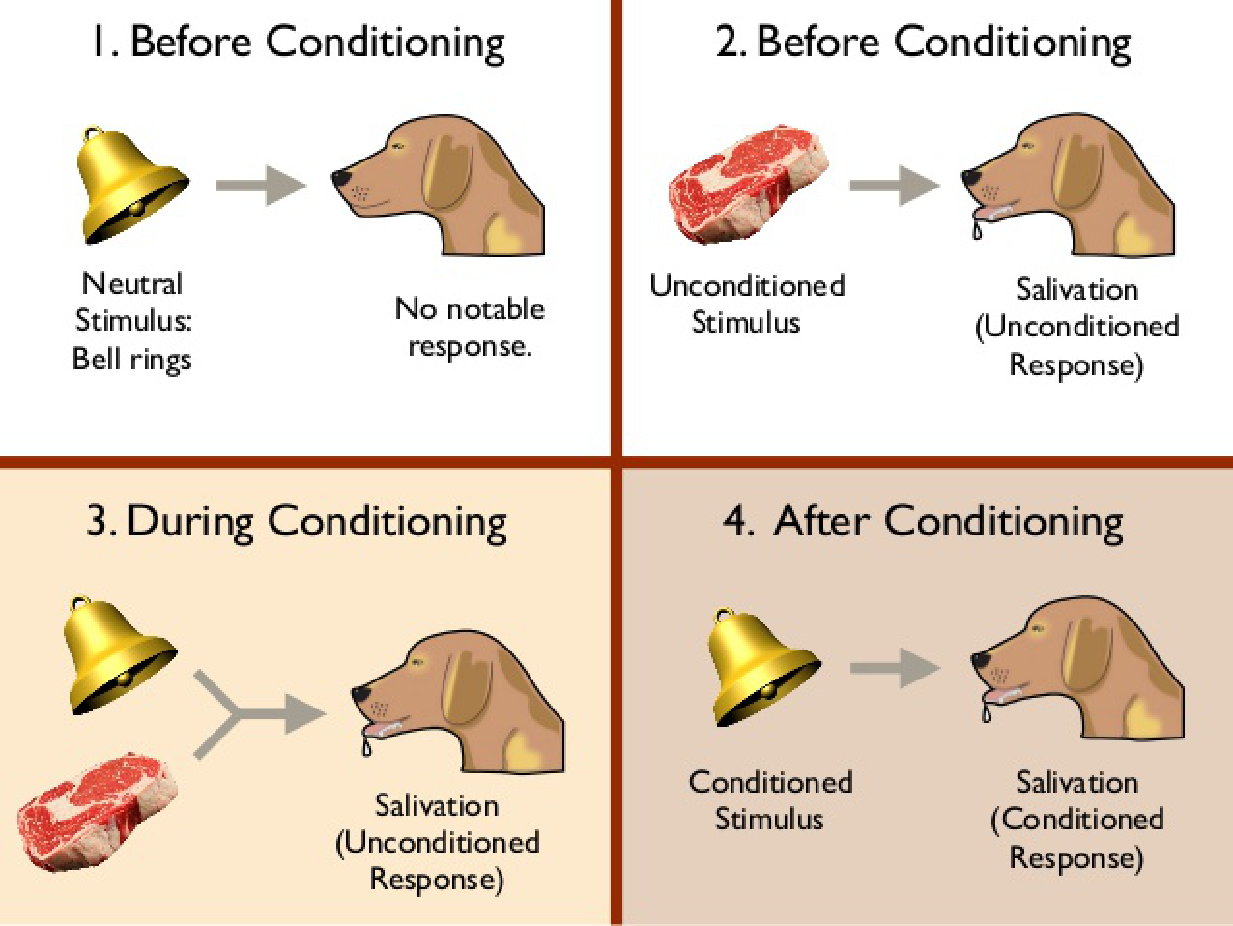

1. Classical conditioning 经典条件反射

Classical conditioning

- A learning procedure; when a stimulus that initially produces no particular response is followed several times by an unconditional stimulus that produces a defensive or appetitive response (the unconditional response), the first stimulus (now called a conditional stimulus) itself evokes the response (now called a conditional response).

Classical conditioning is a form of learning in which an unimportant stimulus acquires the properties of an important one.

- It involves an association between two stimuli.

A stimulus that previously had little effect on behavior becomes able to evoke a reflexive, species-typical behavior.

For example, a defensive eyeblink response can be conditioned to a tone. If we direct a brief puff of air toward a rabbit’s eye, the eye will automatically blink. The response is called an unconditional response (UR) because it occurs unconditionally, without any special training. The stimulus that produces it (the puff of air) is called an unconditional stimulus (US) . Now we begin the training. We present a series of brief 1000-Hz tones, each followed 500 ms later by a puff of air. After several trials the rabbit’s eye begins to close even before the puff of air occurs. Classical conditioning has occurred; the conditional stimulus (CS —the 1000-Hz tone) now elicits the conditional response (CR–the eye blink).

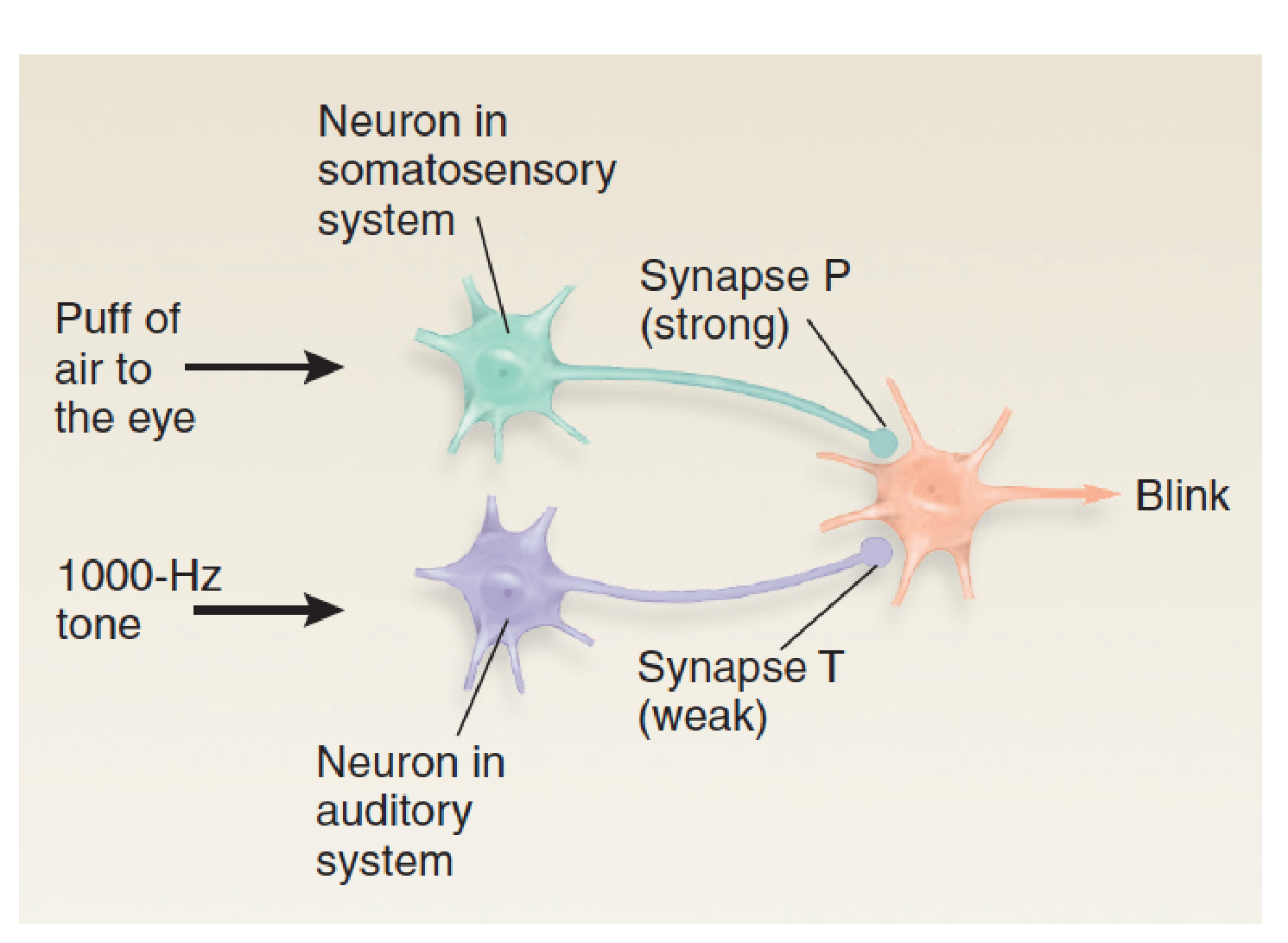

A Simple Neural Model of Classical Conditioning

When classical conditioning takes place, what kinds of changes occur in the brain? :

- When the 1000-Hertz tone is presented just before the puff of air to the eye, synapse T is strengthened.

- This figure shows a simplified neural circuit that could account for this type of learning.

- For the sake of simplicity we will assume that the US (the puff of air) is detected by a single neuron in the somatosensory system and that the CS (the 1000-Hz tone) is detected by a single neuron in the auditory system.

- We will also assume that the response—the eye blink—is controlled by a single neuron in the motor system.

If we present a 1000-Hz tone, we find that the animal makes no reaction because the synapse connecting the tone-sensitive neuron with the neuron in the motor system is weak.

That is, when an action potential reaches the terminal button of synapse T (tone), the excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) that it produces in the dendrite of the motor neuron is too small to make that neuron fire.

However, if we present a puff of air to the eye, the eye blinks. This reaction occurs because nature has provided the animal with a strong synapse between the somatosensory neuron and the motor neuron that causes a blink (synapse P, for “puff”).

To establish classical conditioning, we first present the 1000-Hz tone and then quickly follow it with a puff of air. After we repeat these pairs of stimuli several times, we find that we can dispense with the air puff; the 1000-Hz tone produces the blink all by itself.

Hebb rule

Donald Hebb proposed a rule that might explain how neurons are changed by experience in a way that would cause changes in behavior (Hebb, 1949). 、

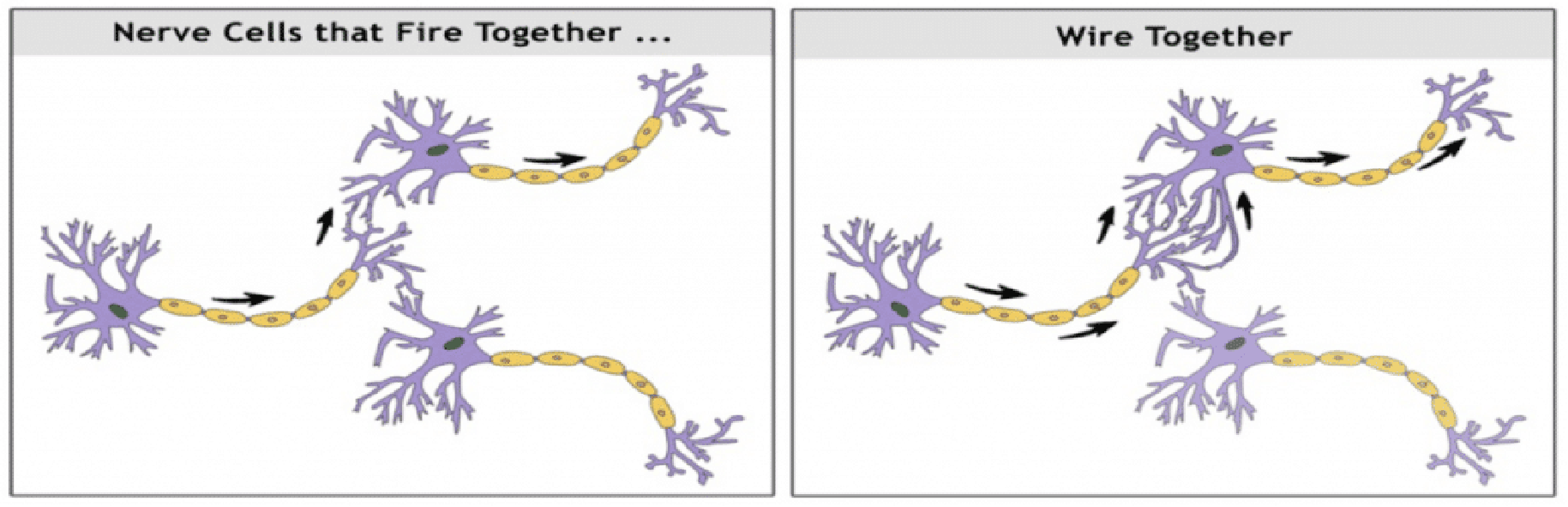

The Hebb rule says that if a synapse repeatedly becomes active at about the same time that the postsynaptic neuron fires, changes will take place in the structure or chemistry of the synapse that will strengthen it.

How would the Hebb rule apply to our circuit?

If the 1000-Hz tone is presented first, then weak synapse T (for “tone”) becomes active. If the puff is presented immediately afterward, then strong synapse P becomes active and makes the motor neuron fire. The act of firing then strengthens any synapse T with the motor neuron that has just been active.

After several pairings of the two stimuli and after several increments of strengthening, synapse T becomes strong enough to cause the motor neuron to fire by itself. Learning has occurred.

- Donald O. Hebb

- Psychologist

- 1904-1985

Hebb rule

- The hypothesis proposed by Donald Hebb that the cellular basis of learning involves strengthening of a synapse that is repeatedly active when the postsynaptic neuron fires.

Neurons That Fire Together Wire Together.

2. Instrumental conditioning

Instrumental conditioning is also called operant conditioning.

Whereas classical conditioning involves automatic, species-typical responses, instrumental conditioning involves behaviors that have been learned.

Whereas classical conditioning involves an association between two stimuli, instrumental conditioning involves an association between a response and a stimulus.

Instrumental conditioning is a more flexible form of learning. It permits an organism to adjust its behavior according to the consequences of that behavior.

i.e. When a behavior is followed by favorable consequences, the behavior tends to occur more frequently; when it is followed by unfavorable consequences, it tends to occur less frequently. Collectively, “favorable consequences” are referred to as reinforcing stimuli , and “unfavorable consequences” are referred to as punishing stimuli .

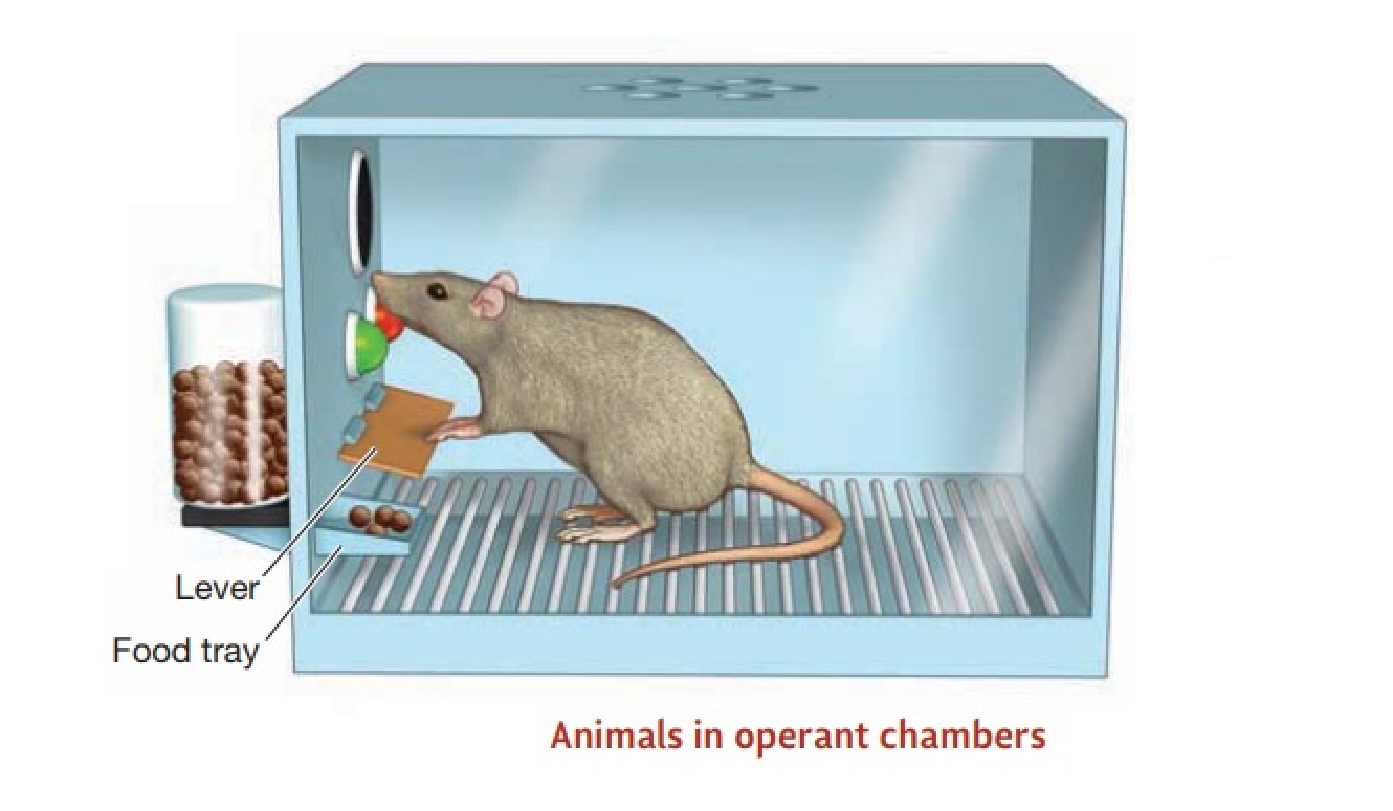

e.g. a response that enables a hungry organism to find food will be reinforced, and a response that causes pain will be punished. (Psychologists often refer to these terms as reinforcers and punishers.)、Synaptic Plasticity: Long-Term Potentiation and Long-Term Depression

Instrumental conditioning

- A learning procedure whereby the effects of a particular behavior in a particular situation increase (reinforce) or decrease (punish) the probability of the behavior; also called operant conditioning.

Reinforcing stimulus

- An appetitive stimulus that follows a particular behavior and thus makes the behavior become more frequent.

- A learning procedure whereby the effects of a particular behavior in a particular situation increase (reinforce) or decrease (punish) the probability of the behavior; also called operant conditioning.

Punishing stimulus

- An aversive stimulus that follows a particular behavior and thus makes the behavior become less frequent.

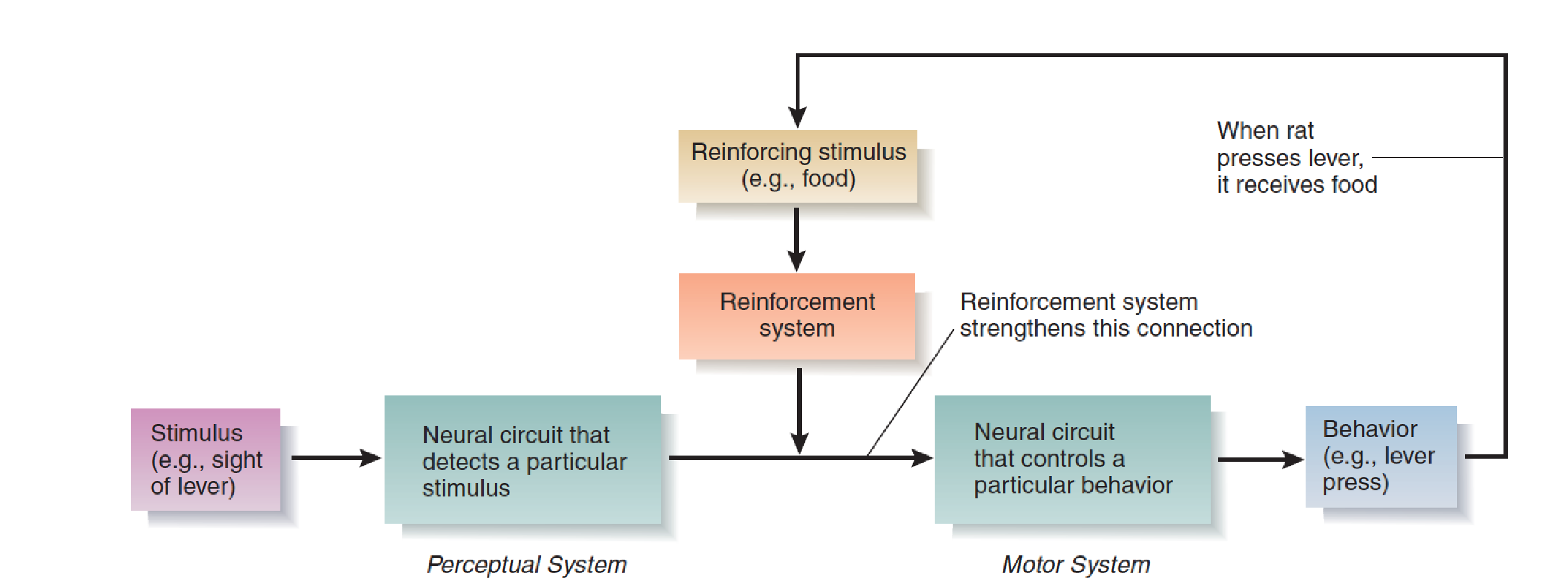

A Simple Neural Model of Instrumental Conditioning

Reinforcement causes changes in an animal’s nervous system that increase the likelihood that a particular stimulus will elicit a particular response.

For example, when a hungry rat is first put in an operant chamber (a “Skinner box”), it is not very likely to press the lever mounted on a wall. However, if it does press the lever and if it receives a piece of food immediately afterward, the likelihood of its making another response increases. Put another way, reinforcement causes the sight of the lever to serve as the stimulus that elicits the lever-pressing response.

Thus, the process of reinforcement strengthens a connection between neural circuits involved in perception (the sight of the lever) and those involved in movement (the act of lever pressing).

The brain contains reinforcement mechanisms that control this process.

Motor learning

Motor learning, is actually a component of stimulus– response learning.

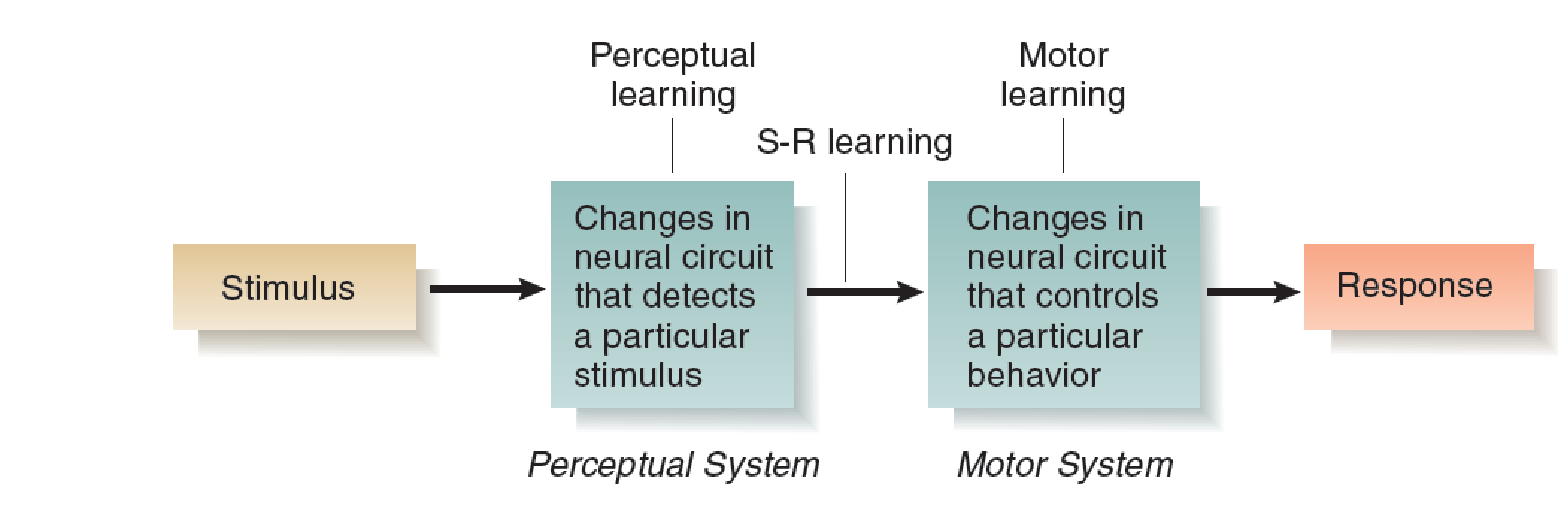

For simplicity’s sake we can think of perceptual learning as the establishment of changes within the sensory systems, stimulus–response learning as the establishment of connections between sensory systems and motor systems, and motor learning as the establishment of changes within motor systems.

An Overview of Perceptual, Stimulus–Response (S-R), and Motor Learning:

A particular learning situation can involve varying amounts of all three types of learning: perceptual, stimulus–response, and motor.

For example, if we teach an animal to make a new response whenever we present a stimulus it has never seen before, it must learn to recognize the stimulus (perceptual learning) and make the response (motor learning), and a connection must be established between these two new memories (stimulus–response learning).

If we teach it to make a response it has already learned whenever we present a new stimulus, only perceptual learning and stimulus–response learning will take place.

Relational Learning

The three forms of learning consist primarily of changes in one sensory system, between one sensory system and the motor system, or in the motor system.

But obviously, learning is usually more complex than that.

The fourth form of learning, relational learning , involves learning the relationships among individual stimuli.

For example, consider what we must learn to become familiar with the contents of a room. First, we must learn to recognize each of the objects. In addition, we must learn the relative locations of the objects with respect to each other. As a result, when we find ourselves located in a particular place in the room, our perceptions of these objects and their locations relative to us tell us exactly where we are.

Other types of relational learning are even more complex.

Episodic learning—remembering sequences of events (episodes) that we witness—requires us to keep track of and remember not only individual events but also the order in which they occur.

A special system that involves the hippocampus and associated structures appears to perform coordinating functions required for many types of learning that go beyond simple perceptual, stimulus–response, or motor learning.

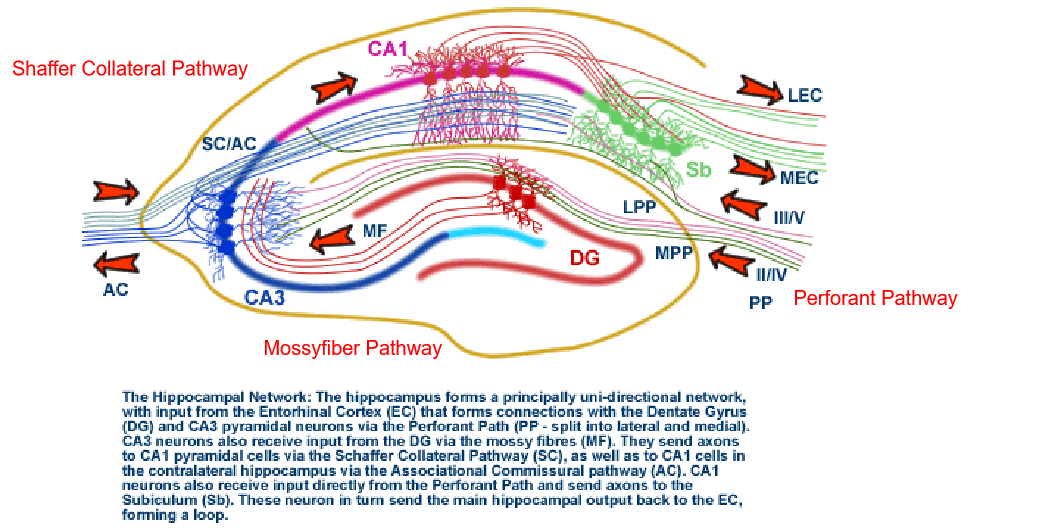

The anatomy and circuitry of the Hippocampus:

二、Synaptic Plasticity: Long-Term Potentiation and Long-Term Depression

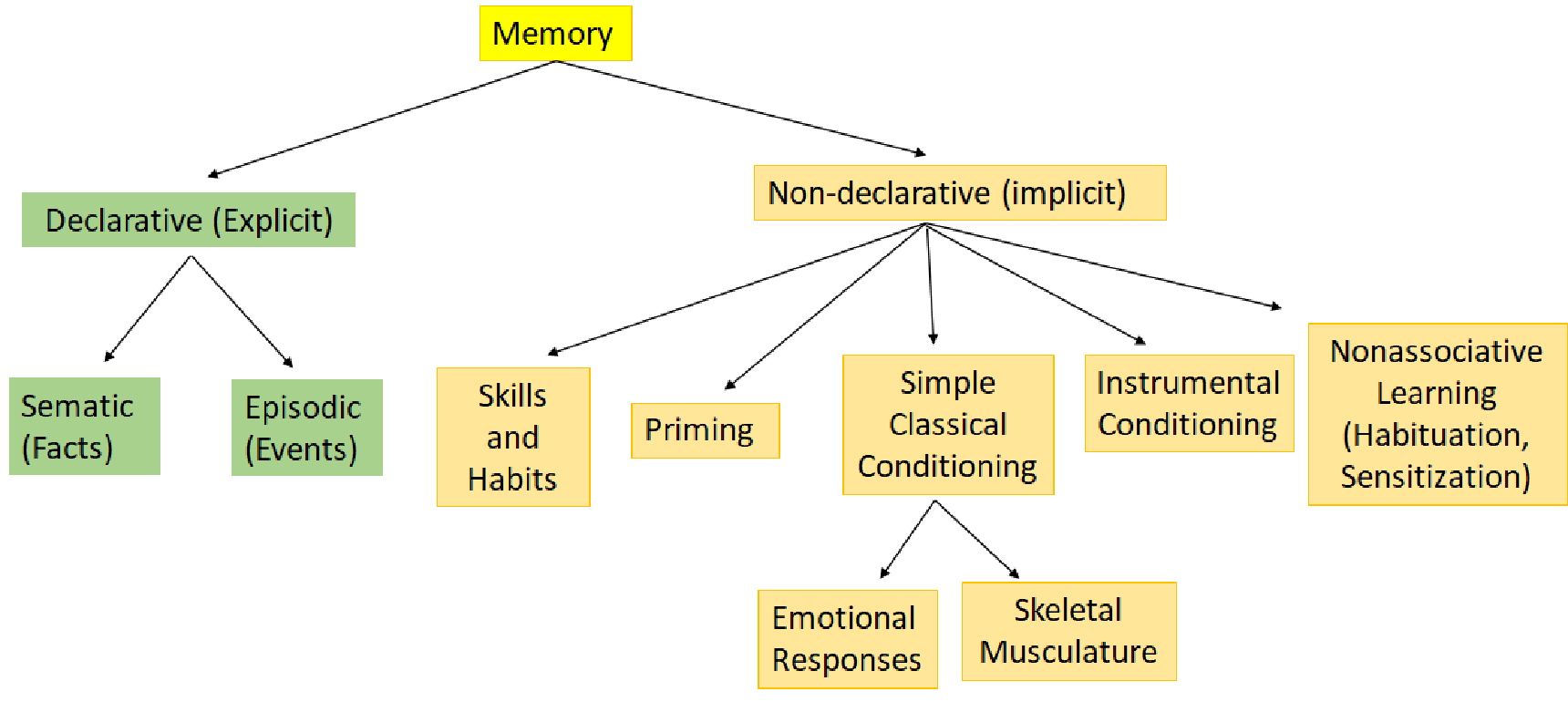

Memory

- Declarative memory is “knowing what” .

- Nondeclarative memory is “knowing how”.

Pavlovian conditioning:

Instrumental conditioning:

1. Aplysia 海兔

Aplysia exhibits simple forms of nondeclarative learning called sensitization.

It is a simple model for the study of cellular mechanisms of learning.

If you give the tail of the animal a weak electric shock or a weak mechanical tap, you will see defensive reflex withdrawals of the tail.

If a strong noxious stimulus (e.g., an electric shock) is delivered to another part of the animal such as its body wall, there will be a more vigorous response to the whole animal.

Now the interesting thing is if you retest the tail of the animal with the same stimulus was presented before, now the withdraw is more vigorous. So the animal learned the environment is dangerous and it adjusted its reflexes accordingly.

This is an example of a simple form of learning called sensitization(敏化).

- It is defined as the enhancement of the response to a test stimulus as a result of delivering a strong generally noxious stimulus to the animal. In a sense, the animal is learning that it is in a “fearful” environment. Sensitization is a ubiquitous form of learning that is exhibited by all animals including humans

Learning must involve synaptic plasticity: changes in the structure or biochemistry of synapses that alter their effects on postsynaptic neurons

Induction of Long-Term Potentiation

Electrical stimulation of circuits within the hippocampal formation can lead to long-term synaptic changes that seem to be among those responsible for learning.

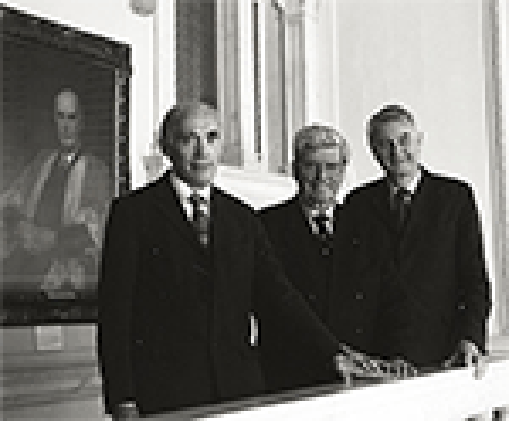

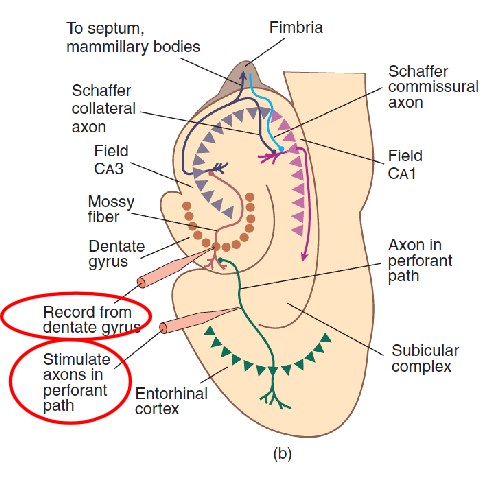

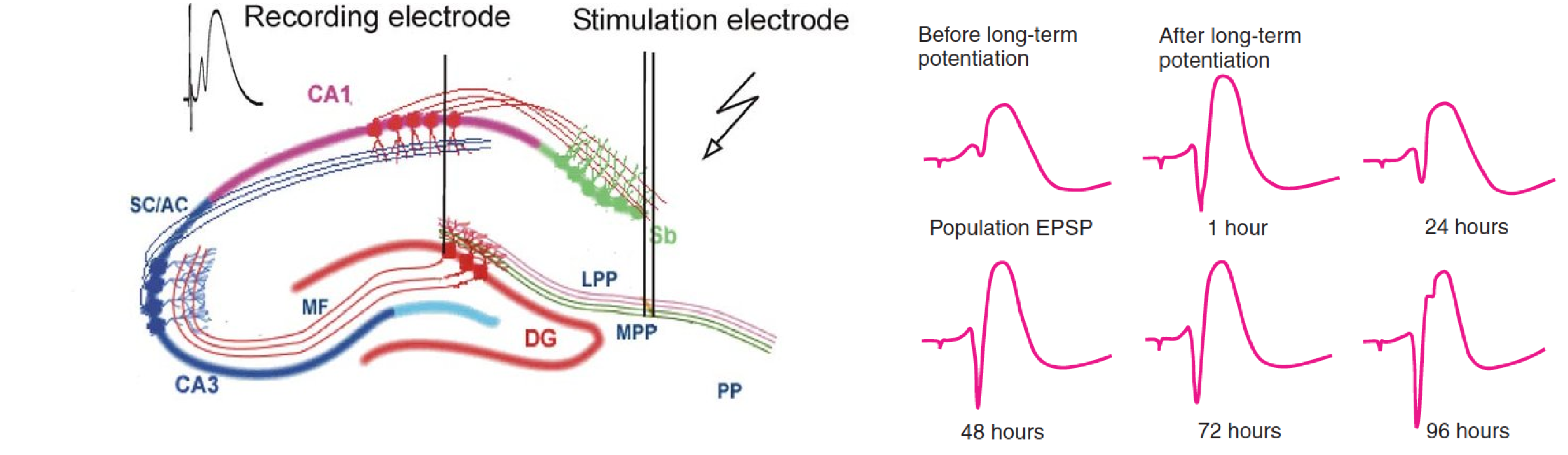

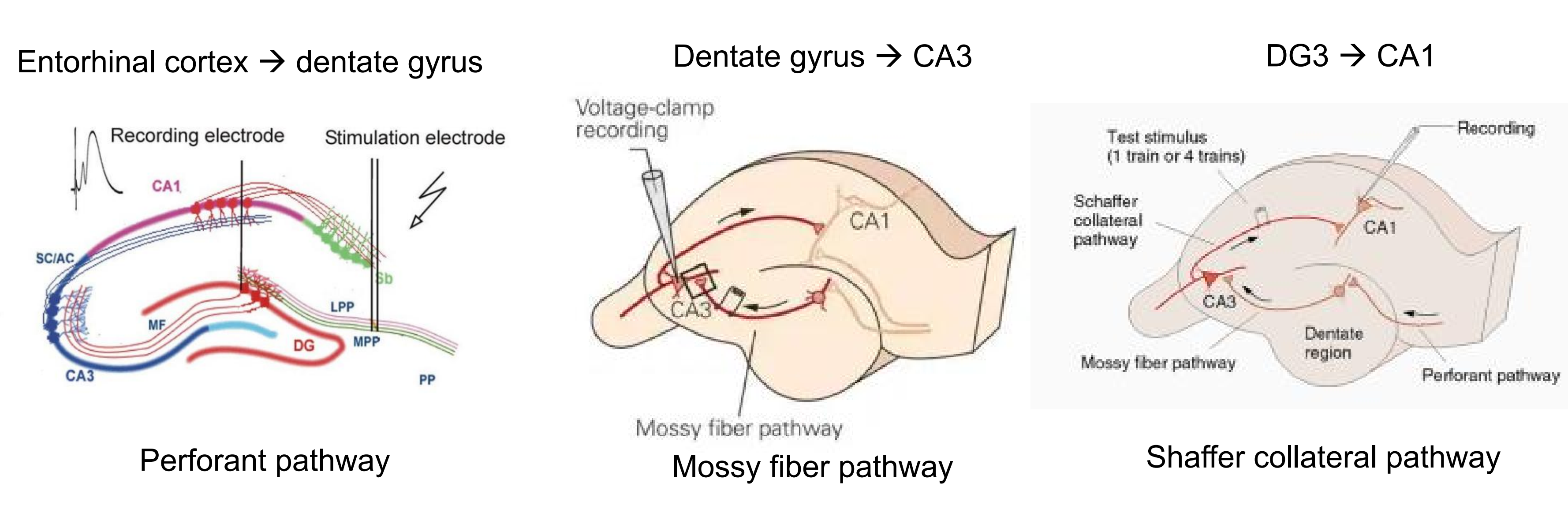

Bliss and Lømo (1970) discovered that intense electrical stimulation of axons leading from the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus caused a long-term increase in the magnitude of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in the postsynaptic neurons; this increase has come to be called long-term potentiation (LTP) .

- Tim Bliss,

- Per Andersen,

- Terje Lømo

1. The Hippocampal Formation and Long-Term Potentiation

- This schematic diagram shows the connections of the components of the hippocampal formation and the procedure for producing long-term potentiation.

2. Long-term potentiation (LTP)

Long-term potentiation (LTP)

- A long-term increase in the excitability of a neuron to a particular synaptic input caused by repeated high-frequency activity of that input.

- Population EPSP (Excitatory PostSynaptic Potentials)

- An evoked potential that represents the EPSPs of a population of neurons.

Long-term potentiation can be produced in other regions of the hippocampal formation and in many other places in the brain.

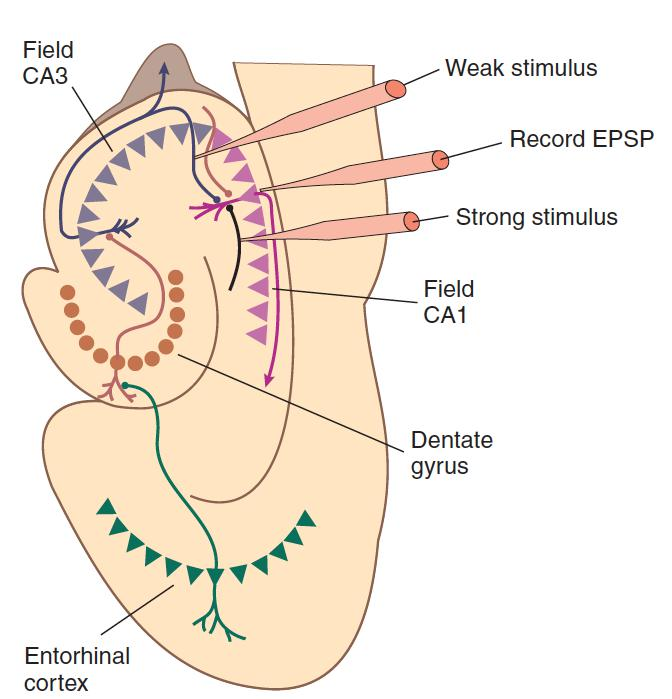

Associative long-term potentiation

- A long-term potentiation in which concurrent stimulation of weak and strong synapses to a given neuron strengthens the weak ones.

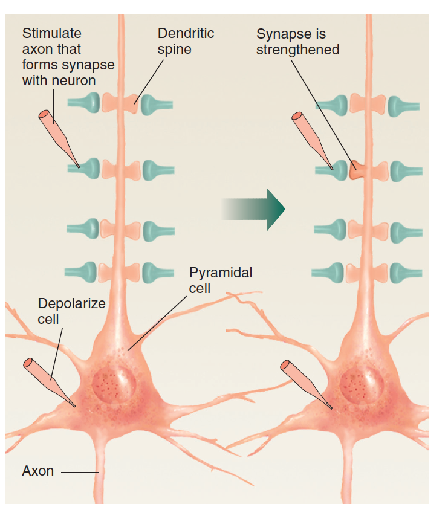

- Many experiments have demonstrated that long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices can follow the Hebb rule. That is, when weak and strong synapses to a single neuron are stimulated at approximately the same time, the weak synapse becomes strengthened. This phenomenon is called associative long-term potentiation, because it is produced by the association (in time) between the activity of the two sets of synapses.

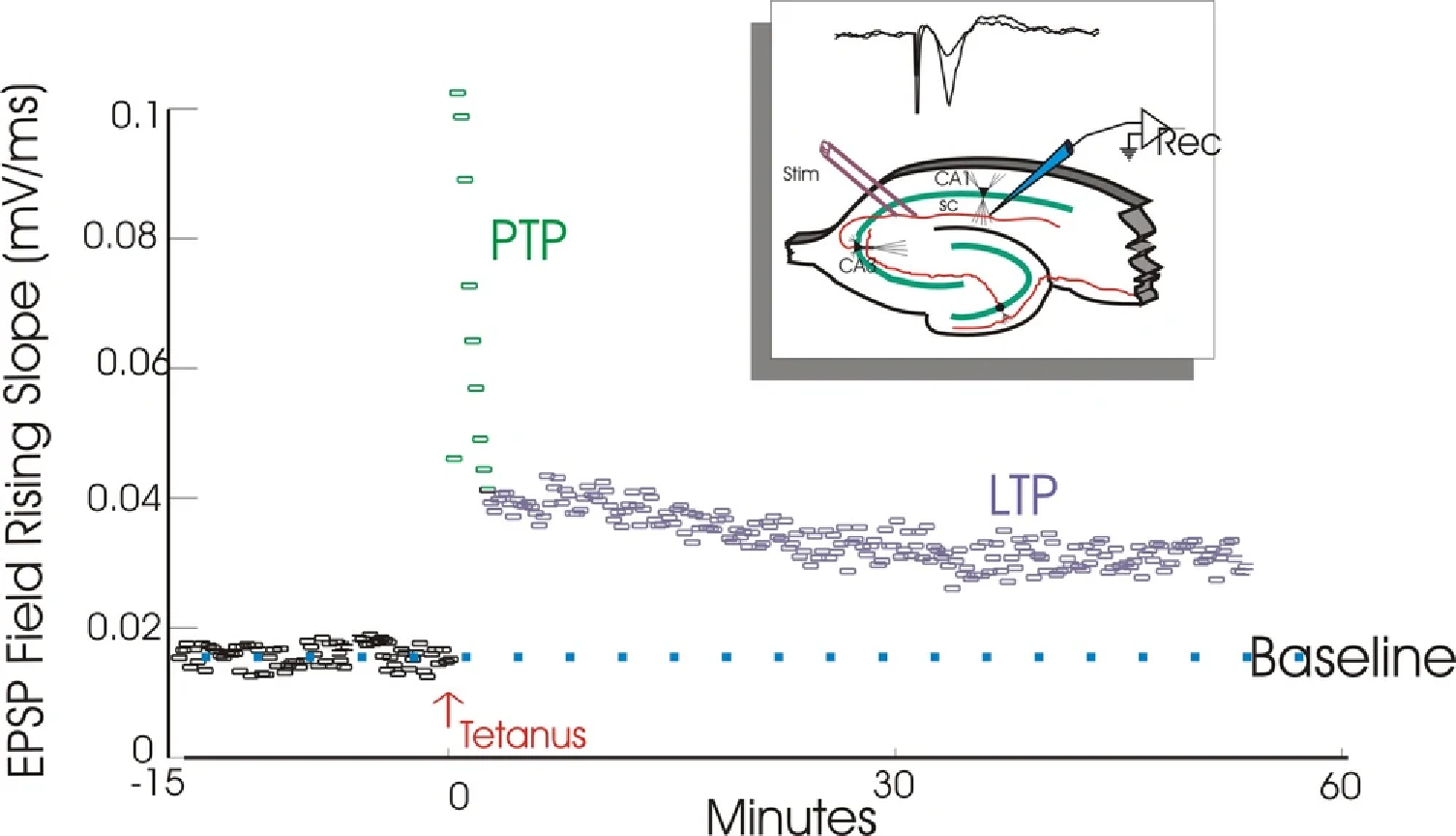

Nonassociative long-term potentiation requires some sort of additive effect. That is, a series of pulses delivered at a high rate all in one burst will produce long-term potentiation, but the same number of pulses given at a slow rate will not.

Homosynaptic long-term potentiation (LTP):

- Posttetanic potentiation (PTP) followed by homosynaptic long-term potentiation (LTP)

The reason for this phenomenon is now clear. Experiments have shown that synaptic strengthening occurs when molecules of the neurotransmitter bind with postsynaptic receptors located in a dendritic spine that is already depolarized.

Kelso, Ganong, and Brown (1986) found that if they used a microelectrode to artificially depolarize neurons in field CA1 and then stimulated the axons that formed synapses with this neuron, the synapses became stronger—that is, they produced a stronger postsynaptic potential in the dendritic spine.

However, if the stimulation of the synapses and the depolarization of the neuron occurred at different times, no effect was seen; thus, the release of the neurotransmitter and depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane had to occur at the same time.

- Synaptic strengthening occurs when synapses are active while the membrane of the postsynaptic cell is depolarized.

Long-term potentiation requires two events: activation of synapses and depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron.

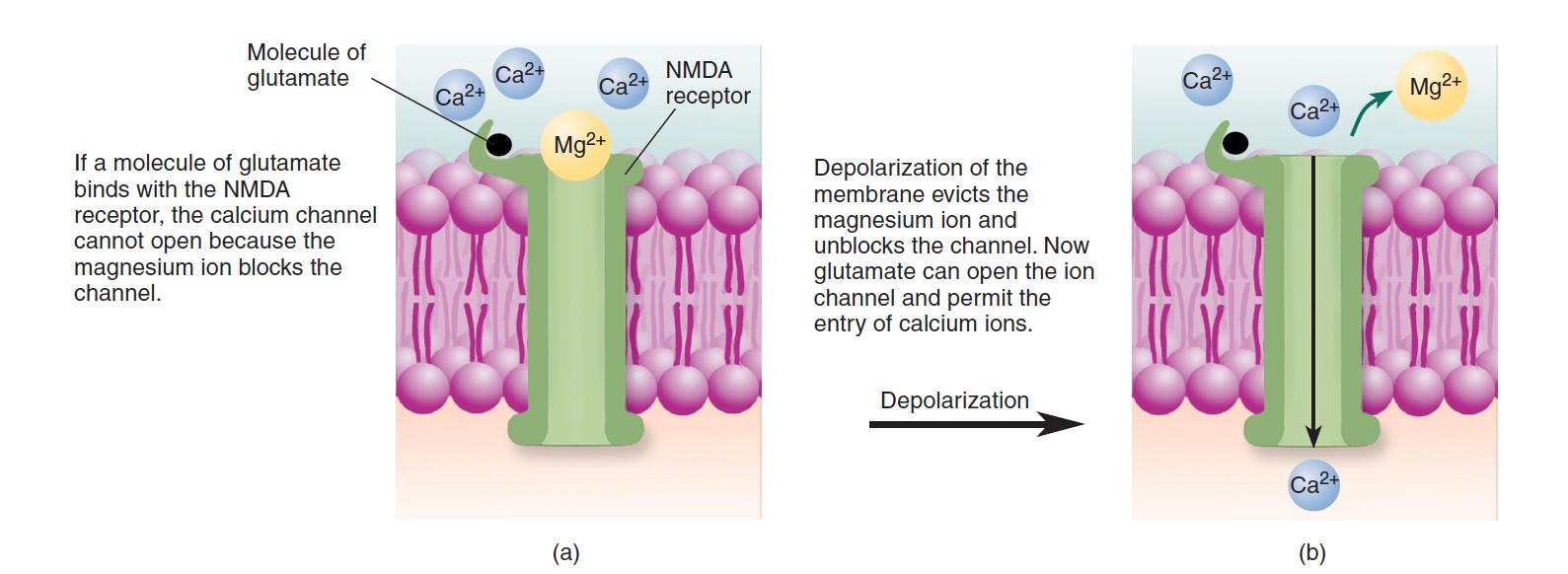

- The explanation for this phenomenon lies in the characteristics of a very special type of glutamate receptor: the NMDA receptor (N-methyl-D-aspartate).

- The NMDA receptor controls a calcium ion channel.

However, this channel is normally blocked by a magnesium ion (Mg2+), which prevents calcium ions from entering the cell even when the receptor is stimulated by glutamate.

But if the postsynaptic membrane is depolarized, the Mg2+ is ejected from the ion channel, and the channel is free to admit Ca2+ ions.

Thus, calcium ions enter the cells through the channels controlled by NMDA receptors only when glutamate is present and when the postsynaptic membrane is depolarized.

This means that the ion channel controlled by the NMDA receptor is a neurotransmitter- and voltage-dependent ion channel.

Role of NMDA Receptors

1. NMDA receptor

The NMDA receptor is a neurotransmitter- and voltage-dependent ion channel. (a) When the postsynaptic membrane is at the resting potential, Mg2+ blocks the ion channel, preventing Ca2+ from entering. (b) When the membrane is depolarized, the magnesium ion is evicted. Thus, the attachment of glutamate to the binding site causes the ion channel to open, allowing calcium ions to enter the dendritic spine.

NMDA receptor

- A specialized ionotropic glutamate receptor that controls a calcium channel that is normally blocked by Mg2+ ions.

- Involved in long-term potentiation.

Cell biologists have discovered that the calcium ion is used by many cells as a second messenger that activates various enzymes and triggers biochemical processes. The entry of calcium ions through the ion channels controlled by NMDA receptors is an essential step in long-term potentiation (Lynch et al., 1984).

AP5 (2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate), a drug that blocks NMDA receptors, prevents calcium ions from entering the dendritic spines and thus blocks the establishment of LTP (Brown et al., 1989).

These results indicate that the activation of NMDA receptors is necessary for the first step in the process of events that establishes LTP: the entry of calcium ions into dendritic spines.

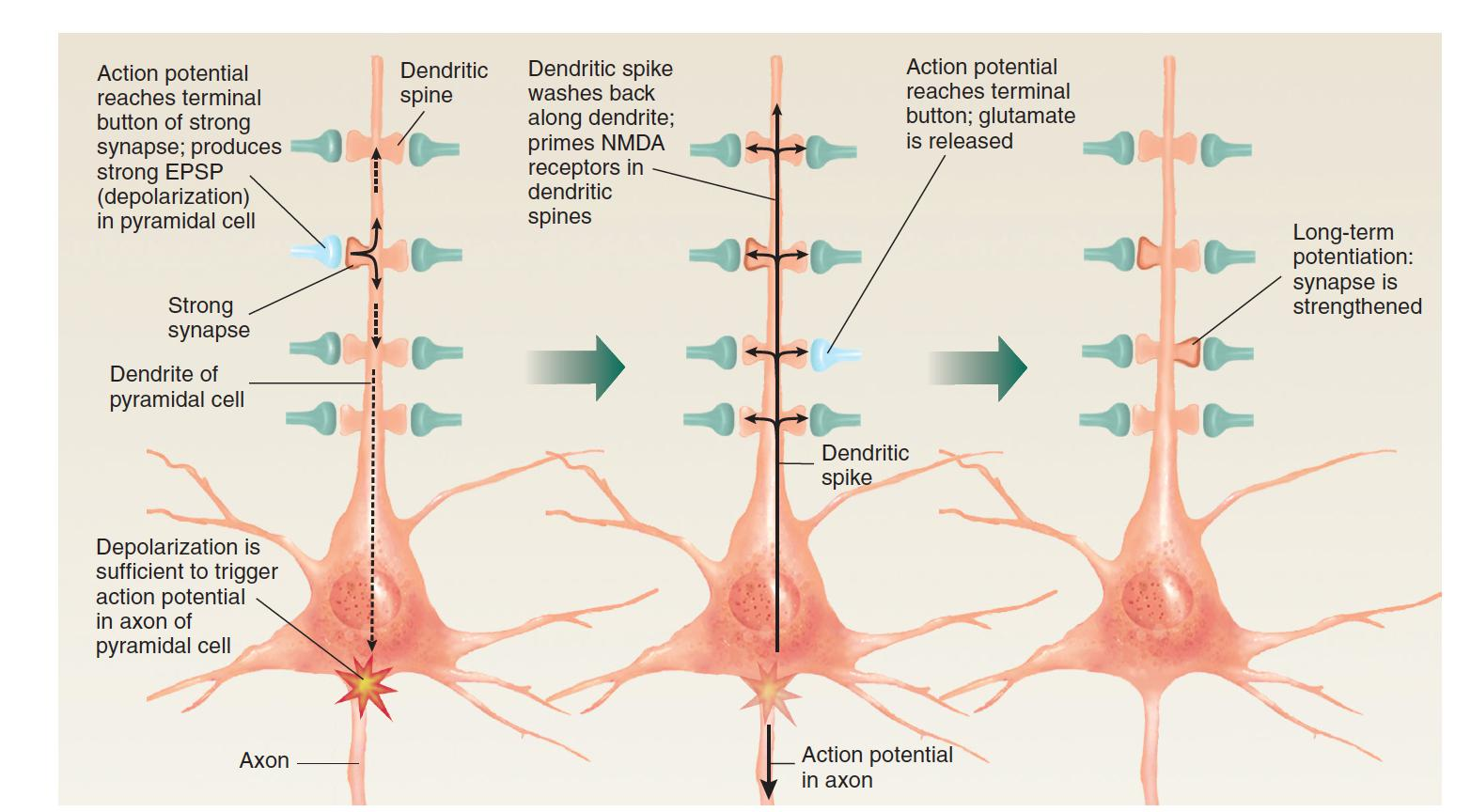

2. Role that NMDA receptors play in this phenomenon

If weak synapses are active by themselves, nothing happens, because the membrane of the dendritic spine does not depolarize sufficiently for the calcium channels controlled by the NMDA receptors to open. (Remember that for these channels to open, the postsynaptic membrane must first depolarize and displace the Mg2+ ions that normally block them.)

However, if the activity of strong synapses located elsewhere on the postsynaptic cell has caused the cell to fire, then a dendritic spike will depolarize the postsynaptic membrane enough for calcium to enter the ion channels controlled by the NMDA receptors. Thus, the special properties of NMDA receptors account not only for the existence of long-term potentiation but also for its associative nature.

3.Associative Long-Term Potentiation

If the activity of strong synapses is sufficient to trigger an action potential in the neuron, the dendritic spike will depolarize the membrane of dendritic spines, priming NMDA receptors so that any weak synapses active at that time will become strengthened.

Mechanisms of Synaptic Plasticity

What is responsible for the increases in synaptic strength that occur during long-term potentiation?

Dendritic spines on CA1 pyramidal cells contain two types of glutamate receptors: NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors .

Research indicates that strengthening of an individual synapse is accomplished by insertion of additional AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane of the dendritic spine (Shi et al., 1999).

AMPA receptors control sodium channels; thus, when they are activated by glutamate, they produce EPSPs in the membrane of the dendritic spine.

Therefore, with more AMPA receptors present, the release of glutamate by the terminal button causes a larger excitatory postsynaptic potential. In other words, the synapse becomes stronger.

1. Where do these new AMPA receptors come from?

Makino and Malinow (2009) used a two-photon laser scanning microscope to watch the movement of AMPA receptors in dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slices.

They found that the establishment of LTP first caused movement of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membranes of dendritic spines from adjacent nonsynaptic regions of the dendrites. Several minutes later, AMPA receptors were carried from the interior of the cell to the dendritic shaft, where they replaced the AMPA receptors that had been inserted in the postsynaptic membrane of the spines.

2. Role of AMPA Receptors in Long-Term Potentiation.

- Two-photon laser scanning microscopy of the CA1 region of living hippocampal slices shows delivery of AMPA receptors into dendritic spines after long-term potentiation.

How does the entry of calcium ions into the dendritic spine cause AMPA receptors to move into the postsynaptic membrane?

This process appears to begin with the activation of several enzymes, including CaM-KII (type II calcium-calmodulin kinase), an enzyme found in dendritic spines.

CaM-KII is a calcium-dependent enzyme, which is inactive until a calcium ion binds with it and activates it.

CaM-KII plays a critical role in long-term potentiation.

Silva et al. (1992) found that LTP could not be established in field CA1 of hippocampal slices taken from mice with a targeted mutation against the gene responsible for the production of CaM-KII.

A two-photon laser scanning microscope study by Shen and Meyer (1999) found that after LTP was established in cultured hippocampal neurons, CaM-KII molecules accumulated in the postsynaptic densities of dendritic spines.

Lledo et al. (1995) found that injection of activated CaM-KII directly into CA1 pyramidal cells strengthened synaptic transmission in those cells.

AMPA receptor

- An ionotropic glutamate receptor that controls a sodium channel; when open, it produces EPSPs.

CaM-KII

- Type II calcium-calmodulin kinase, an enzyme that must be activated by calcium; may play a role in the establishment of long-term potentiation.

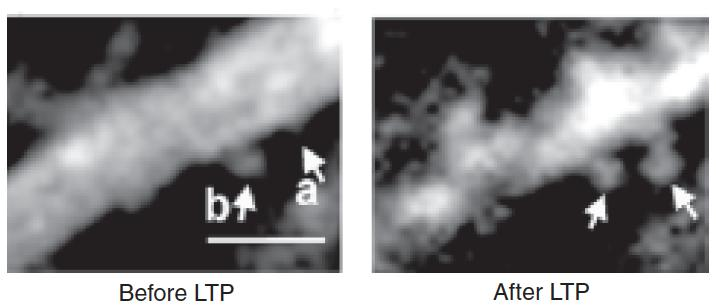

Two other changes that accompany LTP are alteration of synaptic structure and production of new synapses.

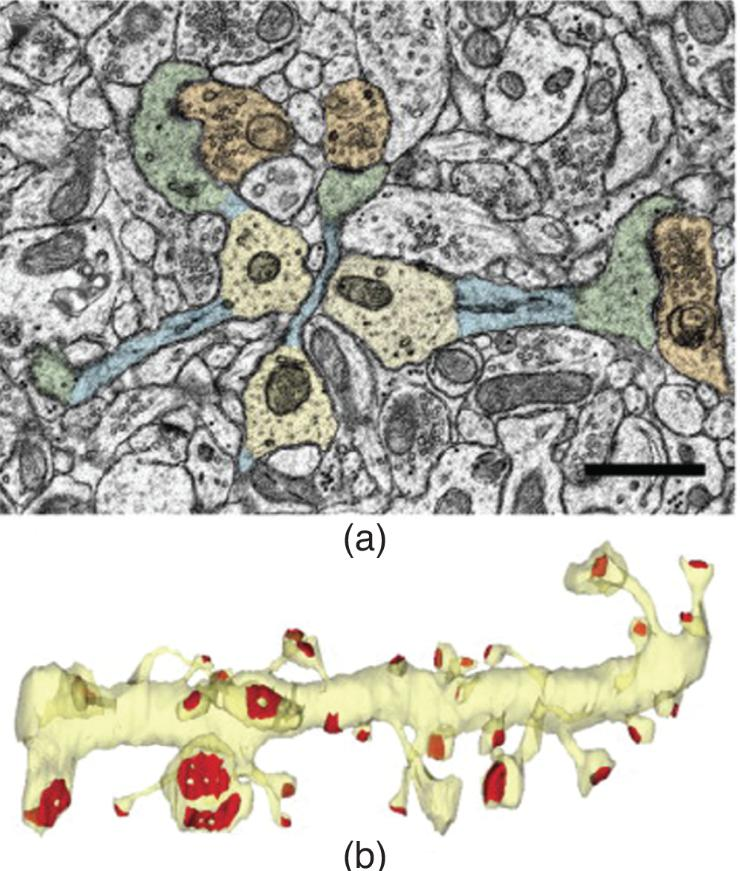

Dendritic Spines in Field CA1

- According to Bourne and Harris (2007), long-term potentiation may convert thin spines into mushroom-shaped spines. (a) Colorized photomicrograph. Dendrite shafts are yellow, spine necks are blue, spine heads are green, and presynaptic terminals are orange. (b) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a portion of a dendrite (yellow) showing the variation in size and shape of postsynaptic densities (red).

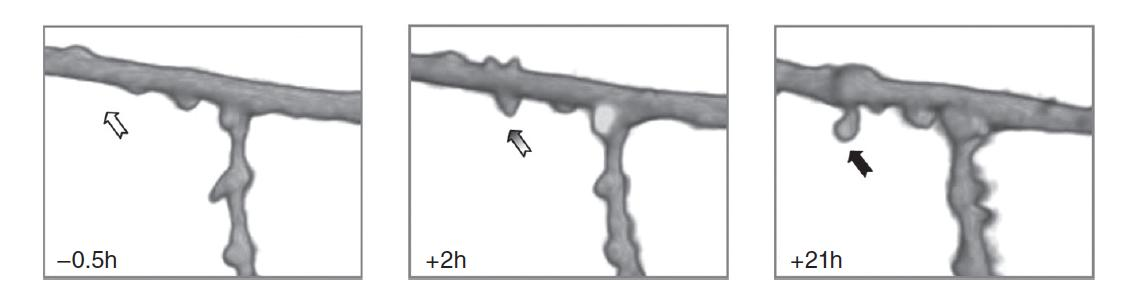

After about 15-19 hours, the new spines formed synaptic connections with terminals of nearby axons

- Two-photon microscopic images show a segment of a dendrite of a CA1 pyramidal neuron before and after electrical stimulation that established long-term potentiation. Numbers in each box indicate the time before or after the stimulation.

3. Presynaptic or postsynaptic mechanism

Postsynaptic mechanism: increase of AMPA receptors in the postsynaptic membrane

Presynaptic mechanism: increase in the amount of glutamate that is released by the terminal button.

How could a process that begins postsynaptically, in the dendritic spines, cause presynaptic changes?

A possible answer comes from the discovery that a simple molecule, nitric oxide (NO), can communicate messages from one cell to another.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a soluble gas produced from the amino acid arginine by the activity of an enzyme known as nitric oxide synthase.

Several experiments suggest that NO may indeed be a retrograde messenger (messages sent from the dendritic spine back to the terminal button) that contributes to the formation of LTP.

Once produced, NO lasts only a short time before it is destroyed. Thus, if it were produced in dendritic spines in the hippocampal formation, it could diffuse only as far as the nearby terminal buttons, where it might produce changes related to the induction of LTP.

4. Early-LTP and Late-LTP

LTP consists of several stages.

Early LTP (E-LTP) involves the process :

- membrane depolarization,

- release of glutamate,

- activation of NMDA receptors,

- entry of calcium ions,

- activation of enzymes such as CaM-KII,

- movement of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane.

- ….(to be continued)

**Long-lasting LTP (L-LTP)**—that is, LTP that lasts more than a few hours—requires protein synthesis.

Frey et al. (1988) found that drugs that blocked protein synthesis also prevented the establishment of L-LTP in field CA1.

If the drug was administered before, during, or immediately after a prolonged burst of stimulation was delivered, E-LTP occurred, but it disappeared a few hours later.

However, if the drug was administered one hour after the synapses had been stimulated, the LTP persisted.

Apparently, the protein synthesis is not necessary for the establishment of E-LTP, but it is required for establishing the later phase of long-lasting LTP, which normally occurs within an hour of the establishment of E-LTP.

What protein (or proteins) might be required for the establishment of L-LTP?

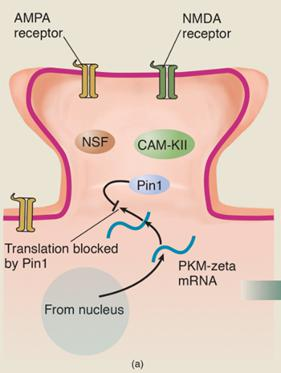

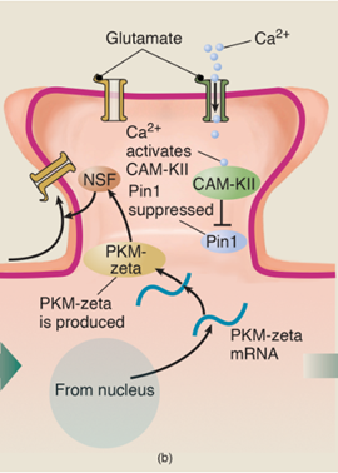

- For several years, investigators have realized that a special enzyme, PKMζ (PKM-zeta ), plays a role in this process.

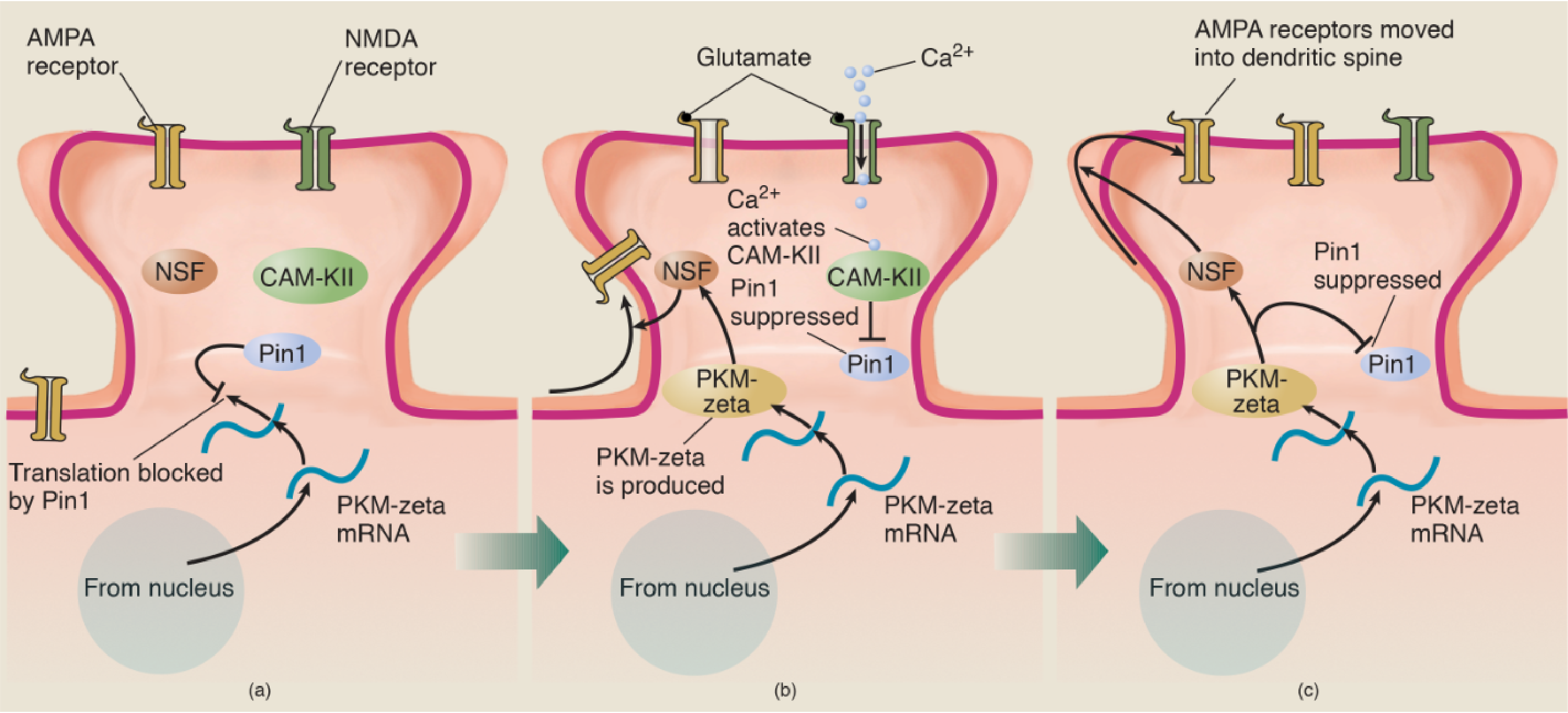

- The gene responsible for the production of PKM-zeta is constantly active, transcribing the DNA of the gene into messenger RNA, which is transported to the vicinity of the dendritic spines. An enzyme called Pin1 inhibits translation of PKM-zeta mRNA into the PKM-zeta protein. Because messenger RNA has only a limited life, only a limited amount of this mRNA accumulates.

- Now, let’s suppose that the conditions for LTP are met: The dendritic spine is depolarized and glutamate is released by the terminal button. The NMDA receptors open and calcium ions enter the dendritic spine.

- The entry of calcium ions activates several enzymes, including CaM-KII.

- The activated enzymes bind with Pin1 and deactivate it, which permits the synthesis of PKM-zeta to take place.

- PKM-zeta acativate enzyme NSF, which stimulates the transport of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane of the dendritic spine. The addition of AMPA receptors produces the first stage, E-LTP.

- PKM-zeta has several effects besides stimulating the transport of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane.

- It also starts a positive feedback loop. It binds with Pin1 and deactivates it, which guarantees that its own synthesis will continue.

- CaM-KII and the other enzymes, which initially deactivated Pin1 and enabled the process of E-LTP to take place, are no longer needed

- The self-sustaining synthesis of PKM-zeta makes long-term LTP possible.

5. Role of PKM-Zeta in Long-Lasting Long-Term Potentiation

- (a) The messenger RNA for PKM-zeta is constantly transcribed from DNA in the nucleus and transported to dendritic spines. However, the action of the enzyme Pin1 blocks the translation of the mRNA into the PKM-zeta protein. (b) When the conditions for LTP are met, Ca2+ ions enter the spine and activate several enzymes, including CaM-KII. This enzyme then suppresses the action of Pin1, which permits PKM-zeta mRNA to direct the production of the PKM-zeta protein, which activates the enzyme NSF. Activated NSF initiates the movement of AMPA receptors into the dendritic spine. (c) PKM-zeta not only activates NSF; it suppresses Pin1 and thus ensures that molecules of PKM-zeta protein continue to be produced.

To recapitulate:

E-LTP involves

- entry of calcium ions,

- activation of CaM-KII and other calcium-activated enzymes,

- deactivation of Pin1,

- synthesis of PKM-zeta from its mRNA, and

- transport of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane.

Conversion of E-LTP to L-LTP takes place through another effect of PKM-zeta: continued suppression of Pin1, permitting synthesis of new PKM-zeta molecules as the old ones eventually break apart. Remember, the gene for PKM-zeta is always active, pumping out mRNA in the nucleus of the cell.

L-LTP is the basis for some very important forms of memory, which means that we must understand what makes L-LTP last for so long.

PKM-zeta is both necessary and sufficient for L-LTP.

Infusion of PKM-zeta into CA1 pyramidal cells produces LTP even without stimulation of NMDA receptors or the entry of calcium ions, and infusion of ZIP, a drug that blocks the production of PKM-zeta, abolishes both L-LTP and some forms of long-term memories in many parts of the brain (Sacktor, 2011).

Long-Term Depression

Low-frequency stimulation of the synaptic inputs to a cell can decrease rather than increase their strength. This phenomenon, known as long-term depression (LTD) , also plays a role in learning.

Apparently, neural circuits that contain memories are established by strengthening some synapses and weakening others.

As we saw earlier, LTP occurs when synaptic inputs are activated at the same time that the postsynaptic membrane is strongly depolarized.

In contrast, LTD occurs when the synaptic inputs are activated when the postsynaptic membrane is either weakly depolarized or hyperpolarized.

The early form of LTP involves an increase in the number of AMPA receptors in the postsynaptic membrane of dendritic spines.

LTD appears to involve the opposite: a decrease in the number of AMPA receptors in these spines.

三、Perceptual Learning

Learning enables us to adapt to our environment and to respond to changes in it. In particular, learning provides us with the ability to perform an appropriate behavior in an appropriate situation.

- Perceptual learning involves learning to recognize things.

- Perceptual learning can involve learning to recognize entirely new stimuli, or it can involve learning to recognize changes or variations in familiar stimuli.

- For example, if a friend gets a new hairstyle or replaces glasses with contact lenses, our visual memory of that person changes.

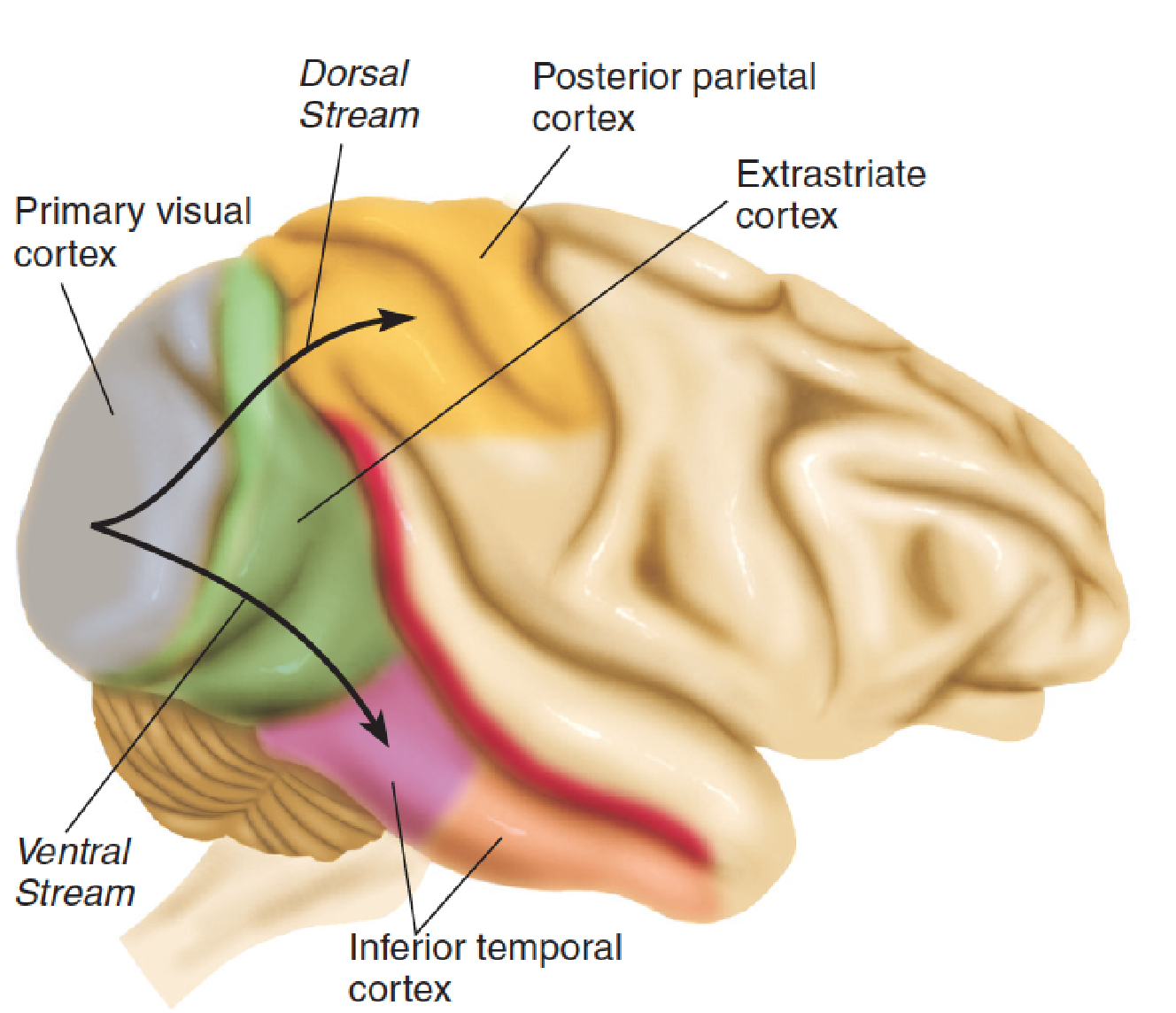

- After analyzing particular attributes of the visual scene, such as form, color, and movement, subregions of the extrastriate cortex send the results of their analysis to the next level of the visual association cortex, which is divided into two “streams.”

- The ventral stream, which is involved with object recognition, continues ventrally into the inferior temporal cortex.

- The dorsal stream, which is involved with perception of the location of objects, continues dorsally into the posterior parietal cortex.

As we saw earlier, people with damage to the inferior temporal cortex may have excellent vision but be unable to recognize familiar, everyday objects such as scissors, clothespins, or light bulbs—as well as faces of friends and relatives.

These lesions impair the ability to perceive (and thus to learn to recognize) particular kinds of visual information.

Perceptual learning clearly involves changes in synaptic connections in the visual association cortex that establish new neural circuits.

- At a later time, when the same stimulus is seen again and the same pattern of activity is transmitted to the cortex, these circuits become active again. \

- This activity constitutes the recognition of the stimulus—the readout of the visual memory, so to speak.

For example, Yang and Maunsell (2004) trained monkeys to detect small differences in visual stimuli whose images were projected onto a specific region of the retina. After the training was complete, the monkeys were able to detect differences much smaller than those they could detect when the training first started. However, they were unable to detect these differences when the patterns were projected onto other regions of the retina.

Recordings of single neurons in the visual association cortex showed that the response properties of neurons that received information from the “trained” region of the retina—but not from other regions—had become sensitive to small differences in the stimuli.

- Clearly, neural circuits in that region alone had been modified by the training.

Let’s look at some evidence from studies with humans that supports the conclusion that activation of neural circuits in the sensory association cortex constitutes the “readout” of a perceptual memory.

Many years ago, Penfield and Perot (1963) discovered that when they stimulated the visual and auditory association cortex as patients were undergoing seizure surgery, the patients reported memories of images or sounds—for example, images of a familiar street or the sound of the patient’s mother’s voice.

Damage to regions of the brain involved in visual perception not only impair the ability to recognize visual stimuli but also disrupt people’s memory of the visual properties of familiar stimuli.

For example, Vandenbulcke et al. (2006) found that Patient J. A., who had sustained damage to the right fusiform gyrus, performed poorly on tasks that required her to draw or describe visual features of various animals, fruits, vegetables, tools, vehicles, or pieces of furniture. Her other cognitive abilities, including the ability to describe nonvisual attributes of objects, were normal. In addition, an fMRI study found that when normal control subjects were asked to perform the visual tasks that she performed poorly, activation was seen in the region of their brains that corresponded to J. A.’s lesion.

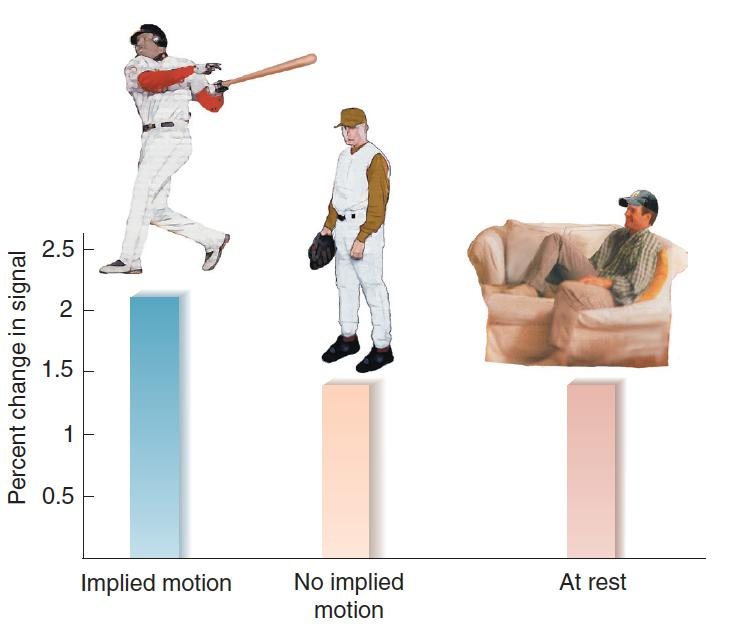

Evidence of Retrieval of Visual Memories of Movement:

- The bars represent the level of activation, measured by fMRI, of MT/MST, regions of the visual association cortex that respond to movement. Subjects looked at photographs of static scenes or scenes that implied motion similar to the ones shown here.

Kourtzi and Kanwisher (2000) found that specific kinds of visual information can activate very specific regions of the visual association cortex.

A region of the visual association cortex, MT/MST, plays an essential role in the perception of movement.

The investigators presented subjects with photographs that implied motion—for example, an athlete getting ready to throw a ball. They found that photographs like these, but not photographs of people remaining still, activated area MT/MST. Obviously, the photographs did not move, but presumably the subjects’ memories contained information about movements they had previously seen.

四、Classical Conditioning

The amygdala is part of an important system involved in a particular form of stimulus–response (S-R) learning: classically conditioned emotional responses.

An aversive stimulus such as a painful foot shock produces a variety of behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal responses: freezing, increased blood pressure, secretion of adrenal stress hormones, and so on. A classically conditioned emotional response is established by pairing a neutral stimulus (such as a tone of a particular frequency) with an aversive stimulus (such as a brief foot shock). After these stimuli are paired, the tone becomes a CS; when it is presented by itself, it elicits the same type of responses as the unconditional stimulus does.

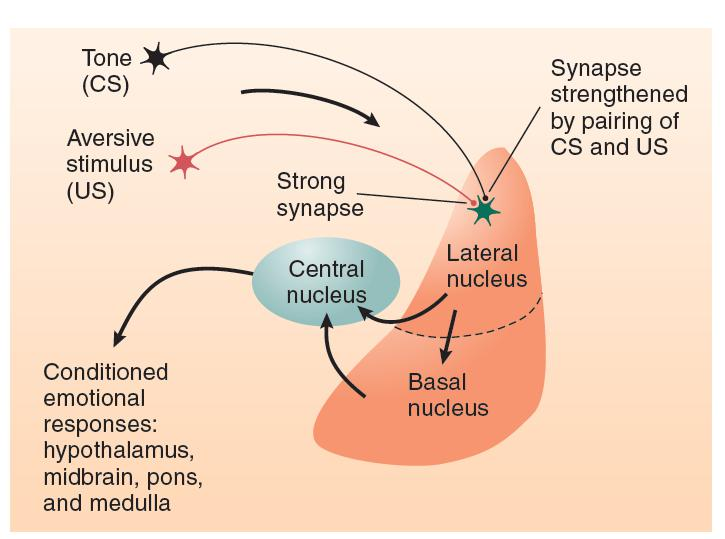

A hypothetical neural circuit for Conditioned Emotional Responses

- The figure shows the probable location of the changes in synaptic strength produced by the classically conditioned emotional response that results from pairing a tone with a foot shock.

Terminal buttons from neurons that transmit auditory and somatosensory information to the lateral nucleus of the amygdala form synapses with dendritic spines on these neurons.

When a rat encounters a painful stimulus, somatosensory input activates strong synapses in the lateral nucleus. As a result, the neurons in this nucleus begin firing, which activates neurons in the central nucleus, evoking an unlearned (unconditional) emotional response. If a tone is paired with the painful stimulus, the weak synapses in the lateral amygdala that respond to the sound of the tone are strengthened through the action of the Hebb rule.

The changes in the lateral amygdala responsible for acquisition of a conditioned emotional response involve LTP.

LTP in many parts of the brain—including the amygdala—is accomplished through the activation of NMDA receptors and the insertion of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane.

For example, Rumpel et al. (2005) paired a tone with a shock and established a conditioned emotional response. They found that the learning experience caused AMPA receptors to be inserted into dendritic spines of synapses between lateral amygdala neurons and axons that provide auditory input. They also found that a procedure that prevented the insertion of AMPA receptors into the dendritic spines also prevented the establishment of fear conditioning.

In addition, Migues et al. (2010) found that blocking the activity of PKM-zeta in the lateral amygdala with an injection of ZIP impaired the establishment of a conditioned emotional response. In fact, the magnitude of the deficit was directly related to the decrease in postsynaptic AMPA receptors.

The results of these studies support the conclusion that LTP in the lateral amygdala, mediated by NMDA receptors and maintained by PKM-zeta, plays a critical role in the establishment of conditioned emotional responses.

五、Instrumental Conditioning

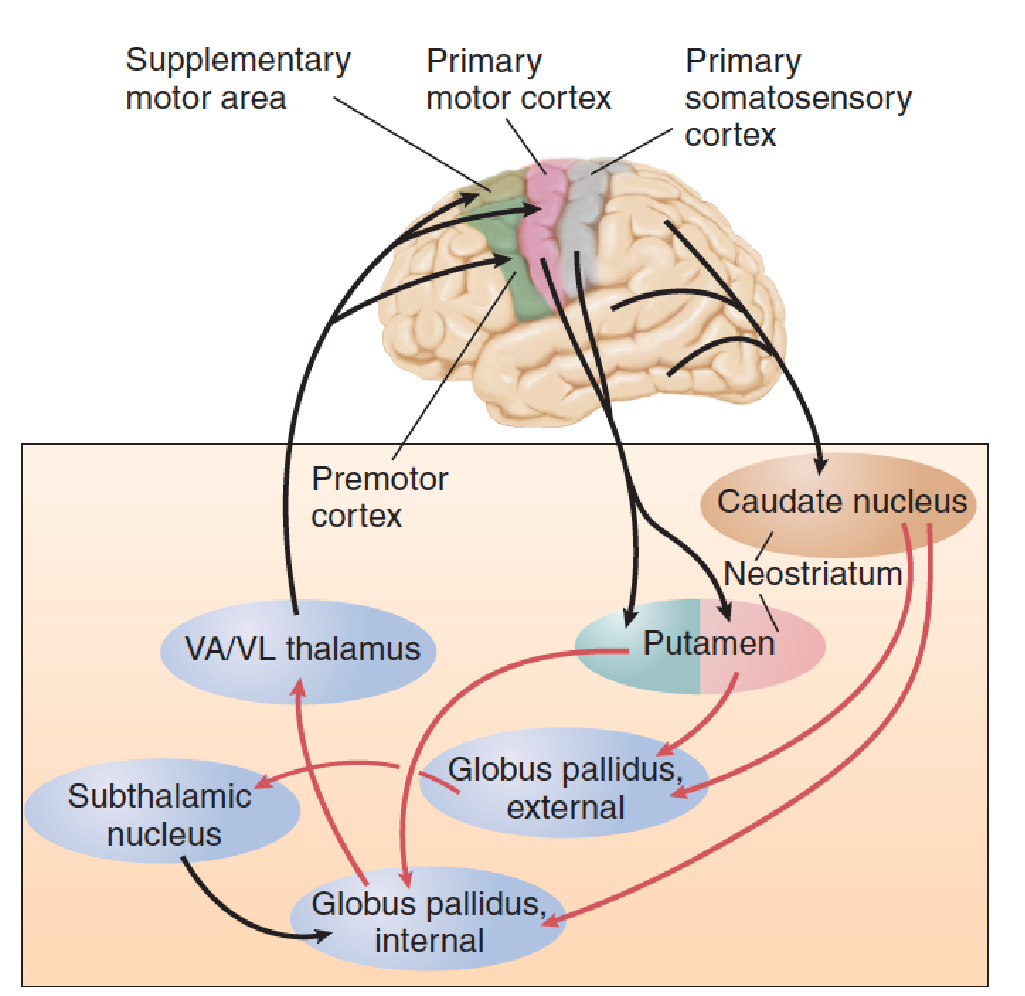

Role of the Basal Ganglia

Instrumental conditioning entails the strengthening of connections between neural circuits that detect a particular stimulus and neural circuits that produce a particular response.

Clearly, the circuits that are responsible for instrumental conditioning begin in various regions of the sensory association cortex, where perception takes place, and end in the motor association cortex of the frontal lobe, which controls movements.

But what pathways are responsible for these connections, and where do the synaptic changes responsible for the learning take place?

There are two major pathways between the sensory association cortex and the motor association cortex:

- direct transcortical connections (connections from one area of the cerebral cortex to another)

- connections via the basal ganglia and thalamus.

Both of these pathways appear to be involved in instrumental conditioning, but they play different roles.

- When people are first learning a complex skill, such as driving a car, they must give it their full attention. Eventually, they can drive without thinking much about it and can easily carry on a conversation with passengers at the same time.

In conjunction with the hippocampal formation, the transcortical connections are involved in the acquisition of episodic memories—complex perceptual memories of sequences of events that we witness or that are described to us.

The transcortical connections are also involved in the acquisition of complex behaviors that involve deliberation or instruction.

For example, a person learning to drive a car with a manual transmission might say, “Let’s see, push in the clutch, move the shift lever to the left and then away from me—there, it’s in gear—now let the clutch come up—oh! It died—I should have given it more gas. Let’s see, clutch down, turn the key. . . .” A memorized set of rules (or an instructor sitting next to us) provides a script for us to follow. Of course, this process does not have to be audible or even involve actual movements of the speech muscles; a person can think in words with neural activity that does not result in overt behavior.

At first, performing a behavior through observation or by following a set of rules is slow and awkward. And because so much of the brain’s resources are involved with recalling the rules and applying them to our behavior, we cannot respond to other stimuli in the environment—we must ignore events that might distract us. But then, with practice, the behavior becomes much more fluid. Eventually, we perform it without thinking and can easily do other things at the same time, such as carrying on a conversation with passengers as we drive our car.

The Basal Ganglia and Their Connections:

The neostriatum—the caudate nucleus and the putamen—receives sensory information from all regions of the cerebral cortex. It also receives information from the frontal lobes about movements that are planned or are actually in progress. (So as you can see, the basal ganglia have all the information they need to monitor the progress of someone learning to drive a car.) The outputs of the caudate nucleus and the putamen are sent to another part of the basal ganglia: the globus pallidus. The outputs of this structure are sent to the frontal cortex: to the premotor and supplementary motor cortex, where plans for movements are made, and to the primary motor cortex, where they are executed.

Studies with laboratory animals have found that lesions of the basal ganglia disrupt instrumental conditioning but do not affect other forms of learning.

For example, Fernandez-Ruiz et al. (2001) destroyed the portions of the caudate nucleus and putamen that receive visual information from the ventral stream in monkeys. They found that although the lesions did not disrupt visual perceptual learning, they impaired the monkeys’ ability to learn to make a visually guided operant response.

Williams and Eskandar (2006) trained monkeys to move a joystick in a particular direction (left, right, forward, or backward) when they saw a particular visual stimulus. Correct responses were reinforced with a sip of fruit juice. As the monkeys learned the task, the rate of firing of single neurons in the caudate nucleus increased. In fact, the activity of caudate neurons was correlated with the animals’ rate of learning. When the investigators increased the activation of caudate neurons through low-intensity, high-frequency electrical stimulation during the reinforcement period, the monkeys learned a particular stimulus–response association more quickly. These results provide further evidence for the role of the basal ganglia in instrumental conditioning.

The transfer of memories from brain systems involved in the acquisition of behavior sequences to those involved in storage of automatic procedures can be seen in the basal ganglia. The dorsomedial (DM) striatum of the rat (which corresponds to the caudate nucleus in humans and other primates) is reciprocally connected with the prefrontal cortex. The dorsolateral (DL) striatum of the rat (which corresponds to the primate putamen) is reciprocally connected to sensory and motor regions of the cortex. Yin et al. (2009) and Thorn et al. (2010) found that the DM striatum was involved in early learning of new skills, but that as practice continued and the behavior became more habitual and automatic, the DL striatum began to take over control of the animal’s behavior.

As we saw in the previous section, long-term potentiation appears to play a critical role in classical conditioning. This form of synaptic plasticity also appears to be involved in instrumental conditioning. Packard and Teather (1997) found that blocking NMDA receptors in the basal ganglia with an injection of AP5 disrupted learning guided by a simple visual cue.

Reinforcement

Learning provides a means for us to profit from experience—to make responses that provide favorable outcomes. When good things happen (that is, when reinforcing stimuli occur), reinforcement mechanisms in the brain become active, and the establishment of synaptic changes is facilitated.

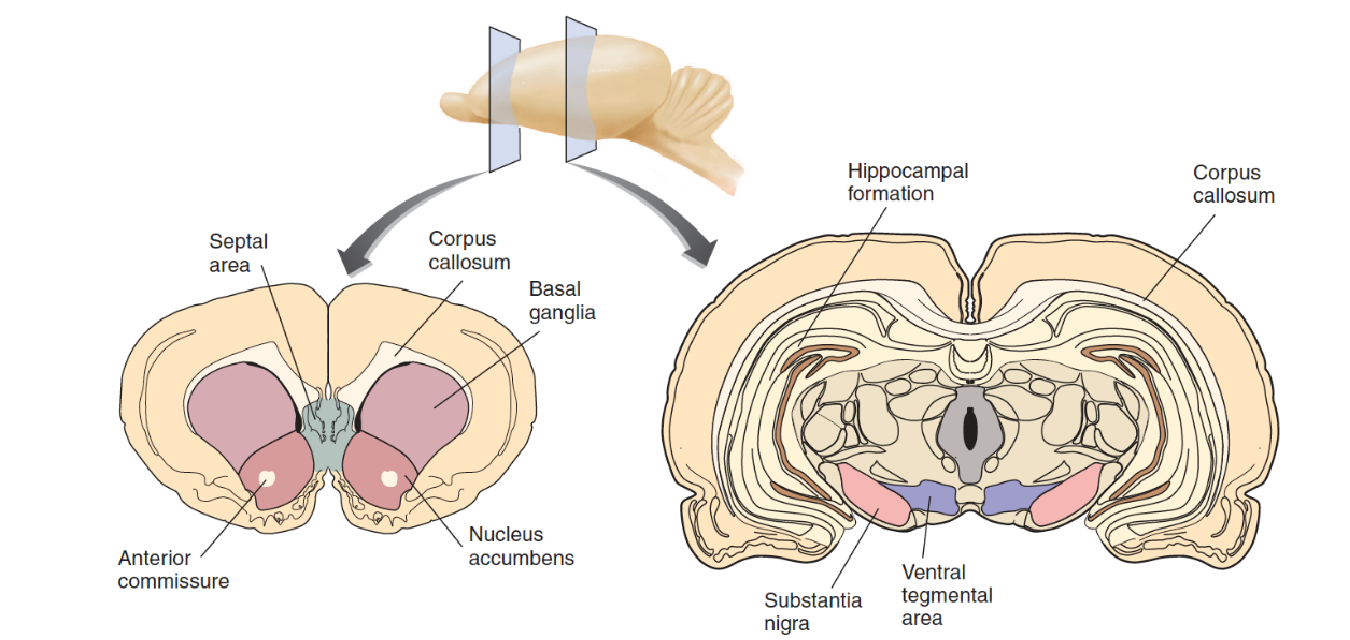

1. Neural Circuits Involved in Reinforcement

Activity of dopaminergic neurons plays a particularly important role in reinforcement.

The mesolimbic system of dopaminergic neurons begins in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain and projects rostrally to several forebrain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens (NAC) .

Neurons in the NAC project to the ventral part of the basal ganglia, which, as we just saw, are involved in learning.

The mesocortical system also plays a role in reinforcement. In addition, this system begins in the ventral tegmental area but projects to the prefrontal cortex, the limbic cortex, and the hippocampus.

2. Functions of the Reinforcement System

A reinforcement system must perform two functions:

- detect the presence of a reinforcing stimulus (that is, recognize that something good has just happened)

- and strengthen the connections between the neurons that detect the discriminative stimulus (such as the sight of a lever) and the neurons that produce the instrumental response (a lever press).

Reinforcement occurs when neural circuits detect a reinforcing stimulus and cause the activation of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area.

In general, if a stimulus causes the animal to engage in an appetitive behavior (that is, if it approaches the stimulus rather than runs away from it), that stimulus can reinforce the animal’s behavior.

When that stimulus occurs, it activates the brain’s reinforcement mechanism, and the link between the discriminative stimulus and the instrumental response is strengthened.

For example, a functional imaging study by Knutson and Adcock (2005) found that anticipation of a reinforcing stimulus (the opportunity to win some money) increased the activation of the ventral tegmentum and some of its projection regions (including the nucleus accumbens) in humans. The investigators also found that the subjects were more likely to remember pictures that they had seen while they were anticipating the chance to win some money.

The prefrontal cortex provides an important input to the ventral tegmental area. The terminal buttons of the axons connecting these two areas secrete glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, and the activity of these synapses makes dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area fire in a bursting pattern, which greatly increases the amount of dopamine they secrete in the nucleus accumbens (Gariano and Groves, 1988).

The prefrontal cortex is generally involved in devising strategies, making plans, evaluating progress made toward goals, and judging the appropriateness of one’s own behavior.

- Perhaps the prefrontal cortex turns on the reinforcement mechanism when it determines that the ongoing behavior is bringing the organism nearer to its goals—that the present strategy is working.

How, exactly, does the release of dopamine facilitate the synaptic changes responsible for instrumental conditioning?

In a review of the literature, Wise (2004) concluded that the release of dopamine in a variety of brain locations affects learning in a variety of tasks and that dopamine plays a critical role in long-lasting long-term potentiation and long-term depression in many brain regions, including the basal ganglia, amygdala, and frontal cortex.

Studies have shown that long-term potentiation is essential for instrumental conditioning and that dopamine is an essential ingredient in long-lasting long-term potentiation. Tsai et al. (2009) used optogenetic stimulation to specifically activate dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and found that the stimulation reinforced an instrumental conditioning preference task.

Navakkode et al. (2010) found that simultaneous application of dopamine and glutamate in hippocampal field CA1 produced L-LTP, but that this effect was prevented by the application of ZIP, which indicates that PKM-zeta is essential for the dopamine-dependent establishment of L-LTP in field CA1—and presumably, of learning that involves synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus.

六、Relational Learning

So far, we has discussed relatively simple forms of learning, which can be understood as changes in circuits of neurons that detect the presence of particular stimuli (perceptual learning) or as strengthened connections between neurons that analyze sensory information and those that produce responses (stimulus-response learning).

But most forms of learning are more complex; most memories of real objects and events are related to other memories.

Seeing a photograph of an old friend may remind you of the sound of the person’s name and of the movements you have to make to pronounce it. You may also be reminded of things you have done with your friend: places you have visited, conversations you have had, experiences you have shared. Each of these memories can contain a series of events, complete with sights and sounds, that you will be able to recall in the proper sequence.

This section discusses research on relational learning, which includes the establishment and retrieval of memories of events, episodes, and places.

Human Anterograde Amnesia 人类的顺行性遗忘

One of the most dramatic and intriguing phenomena caused by human brain damage is anterograde amnesia, which, at first glance, appears to be the inability to learn new information. However, when we examine the phenomenon more carefully, we find that the basic abilities of perceptual learning, stimulus–response learning, and motor learning are intact but that complex relational learning, of the type I just described, is gone.

The term anterograde amnesia refers to difficulty in learning new information. A person with pure anterograde amnesia can remember events that occurred in the past, from the time before the brain damage occurred, but cannot retain information about events encountered after the damage.

Retrograde amnesia 逆行性遗忘

In contrast, retrograde amnesia(逆行性遗忘症) refers to the inability to remember events that happened before the brain damage occurred. Pure anterograde amnesia is rare; usually, there is also a retrograde amnesia for events that occurred for a period of time before the brain damage occurred.

In 1889, Sergei Korsakoff, a Russian physician, first described a severe memory impairment caused by brain damage, and the disorder was given his name.

The most profound symptom of Korsakoff’s syndrome is a severe anterograde amnesia: The patients appear to be unable to form new memories, although they can still remember old ones. They can converse normally and can remember events that happened long before their brain damage occurred, but they cannot remember events that happened afterward.

The brain damage that causes Korsakoff’s syndrome is usually (but not always) a result of chronic alcohol abuse.

Another symptom of Korsakoff’s syndrome is confabulation(虚构) . When people with this disorder are asked about events that occurred recently, they often describe a fictitious event rather than simply saying, “I don’t remember.”

Confabulations can contain mixtures of events that really occurred, or they can be completely imaginary. People who confabulate are not deliberately trying to deceive; they appear to believe that what they are saying really occurred.

1. What Causes Confabulation(虚构)?

Recollecting a memory is a creative process. We do not simply retrieve stored information the way we might check a fact in a book; instead, we take fragmentary information and interpret what that information means.

- Suppose that you are waiting for a bus on a cold, rainy day. As you stand there, musing, you realize that you forgot to pay your rent, which was due several days ago. You resolve to do so as soon as you get home. In fact, you imagine yourself sitting down and writing a check, putting it in an envelope, and carrying it to the mailbox on the corner. However, you meet a friend on the bus, and the interesting conversation you have wipes the thought of paying the rent from your mind. That night, just as you are falling asleep, you suddenly think about the rent. You have a vague memory of writing a check and posting it, but as you think about it more, you realize that you must not have done so, because you remember thinking how glad you were not to have to go out again as you put your wet raincoat away. On further reflection you realize that the memory of writing the check and posting it is simply a memory of your having thought about doing so.

One of the symptoms of Korsakoff’s syndrome is confabulation—the reporting of memories of events that did not really occur. Some of these events are plausible, but some of them are contradicted by other information and cannot possibly be true. However, the stories always contain elements of true events—and people sometimes act on their false beliefs(Schnider, 2003).

For example, a 58-year-old woman believed that she was at home, and not in a hospital, and insisted that she had to feed her baby—even though her “baby” was really 30 years old.

Patients who confabulate do not try to answer questions unrelated to information contained in their memory. Rather, patients who confabulate have difficulty suppressing irrelevant memories of past events that are evoked by stimuli in the present. It is often impossible to convince patients that their confabulations are not real. For example, it was easier to convince the woman who wanted to feed her baby that the baby had already been fed than to convince her that the baby is grown up.

A study by Benson et al. (1996) suggests that confabulation may be caused by brain damage that disrupts the normal functions of the prefrontal cortex.

The investigators reported the case of a man who developed Korsakoff’s syndrome, complete with confabulation. Neuropsychological testing found symptoms that indicate frontal lobe dysfunction, and a PET scan revealed hypoactivity of the medial and orbital prefrontal cortex. Four months later, the confabulation was gone, the neuropsychological tests did not show frontal lobe symptoms, and another PET scan revealed that the activity of the prefrontal cortex was back to normal.

O’Connor et al. (1996) reported a case with complementary findings: A patient who had been amnesic for years had a close-head injury and suddenly began confabulating. Neuropsychological testing found evidence for frontal lobe dysfunction.

Johnson and Raye (1998) suggest that one of the functions of the frontal lobes is to help evaluate the plausibility of a proposition or an ambiguous perception. When information is uncertain, the frontal lobes become involved in retrieving memories that might help us to evaluate whether a given interpretation makes sense.

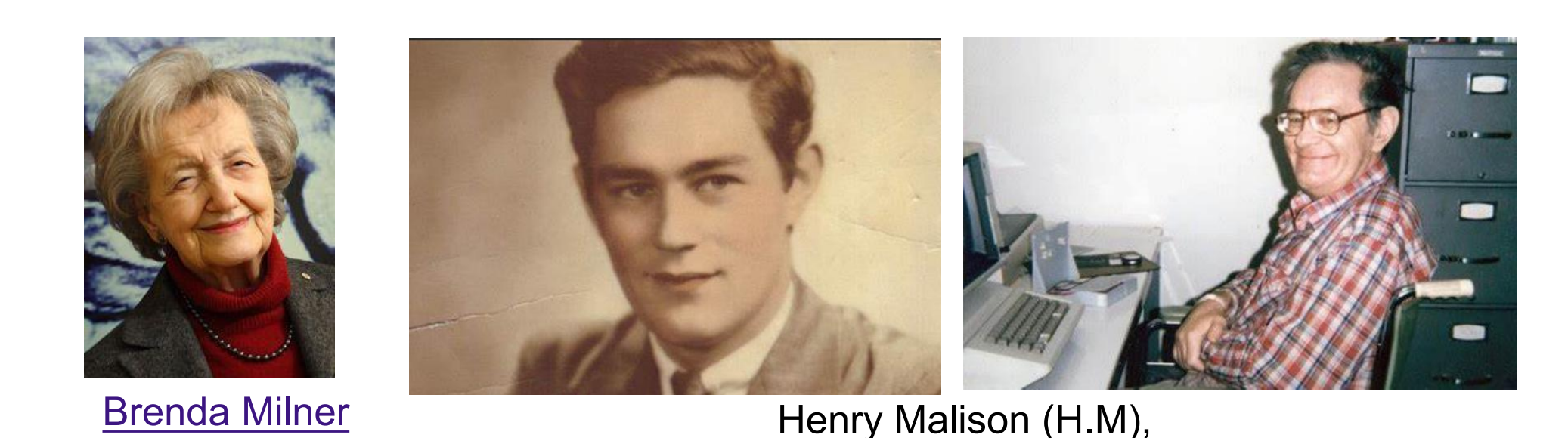

2. Human Anterograde Amnesia

Scoville and Milner (1957) reported that bilateral removal of the medial temporal lobe produced a memory impairment in humans that was apparently identical to that seen in Korsakoff’s syndrome.

Henry Molaison (H.M), received the surgery in an attempt to treat his severe epilepsy

The surgery successfully treated H. M.’s seizure disorder, but it became apparent that the operation had produced a serious memory impairment. Further investigation revealed that the critical site of damage was the hippocampus.

Some interesting facts about H.M.

- Normal behaviors

- Anterograde amnesia

- Only fact or event memory deficits

After the operation, he seemed fairly normal, he had normal conversation with the physician, but he had a very sever memory deficit. Whereas he could remember all of the events prior to the operation, but he could not create new memory for any facts or events. It is supportive of the that the hippocampal region is essential for the formation of memories.

But what’s interesting is that H.M had all of his childish memory. This type of memory deficit is called anterograde amnesia. It means whereas the hippocampus is necessary for new memories, it is not the seat where all the memories are stored. And we now know, they are stored in other cortical areas. So the hippocampus is important for the initial induction of memory, but not ultimatum storage. The process by which an initially labile memory is transformed into a more enduring form is called consolidation.

And what was also interesting about patient H,M is whereas he couldn’t form any new memory for events, he could form new memory for skills. So if you were to teach H.M how to play Ping Pang, he could learning to play Ping Pang very well even if he yet never play it before. But if you asked him, H,M how is it that you know how to play Ping Pang so well, he could say I don’t know, because I never play it in my life, It might comes up naturally. So he could form new memory for skills, habits, but with no conscious recollection that he had those memories.

Milner and her colleagues based the following conclusions on his pattern of deficits:

- The hippocampus is not the location of long-term memories; nor is it necessary for the retrieval of long-term memories. If it were, H. M. would not have been able to remember events from early in his life, he would not have known how to talk, he would not have known how to dress himself, and so on.

- The hippocampus is not the location of immediate (short-term) memories. If it were, H. M. would not be able to carry on a conversation, because he would not have remembered what the other person said long enough to think of a reply.

- The hippocampus is involved in converting immediate (short-term) memories into long-term memories. This conclusion is based on a particular hypothesis of memory function: that our immediate memory of an event is retained by neural activity and that long-term memories consist of relatively permanent biochemical or structural changes in neurons. The conclusion seems a reasonable explanation for the fact that when presented with new information, H. M. seems to understand it and remember it as long as he thought about it but that a permanent record of the information was just never made.

As we will see, these three conclusions are too simple. Subsequent research on patients with anterograde amnesia indicates that the facts are more complicated—and more interesting— than they first appeared to be.

But to appreciate the significance of the findings of more recent research, we must understand these three conclusions and remember the facts that led to them.

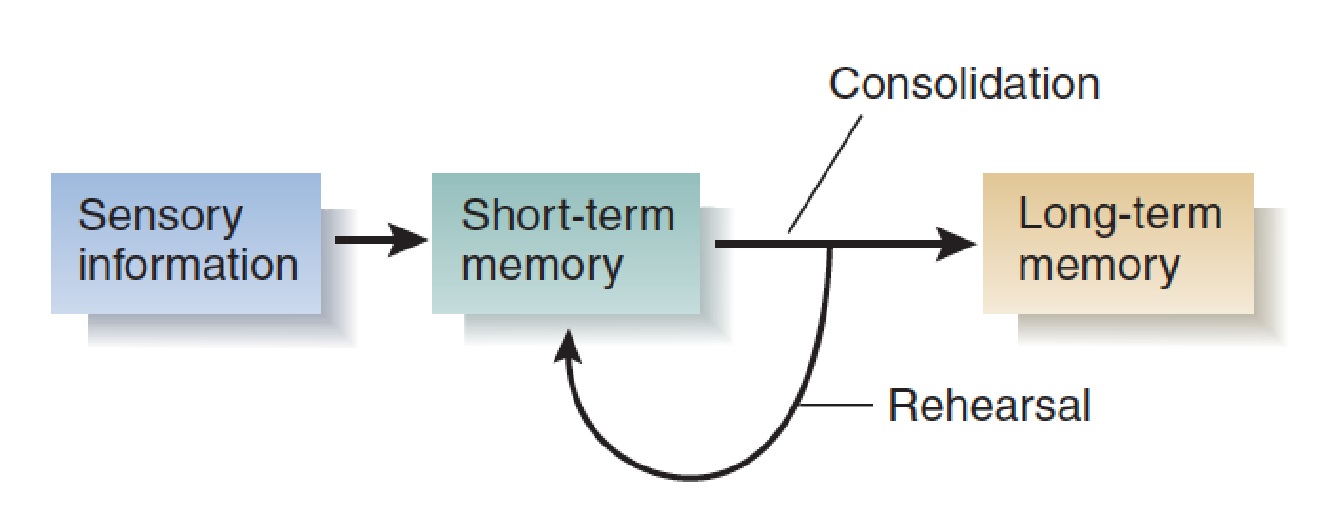

Most psychologists believe that learning consists of at least two stages: short-term memory and long-term memory.

They conceive of short-term memory as a means of storing a limited amount of information temporarily and long-term memory as a means of storing an unlimited amount (or at least an enormously large amount) of information permanently.

We can remember a new item of information (such as a telephone number) for as long as we want to by engaging in a particular behavior: rehearsal. However, once we stop rehearsing the information, we might or might not be able to remember it later; that is, the information might or might not get stored in long-term memory.

The simplest model of the memory process says that sensory information enters short-term memory, rehearsal keeps it there, and eventually, the information makes its way into long-term memory, where it is permanently stored. The conversion of short-term memories into long-term memories has been called consolidation , because the memories are “made solid,” so to speak.

A Simple Model of the Learning Process

- Now you can understand the original conclusions of Milner and her colleagues: If H. M.’s short-term memory were intact and if he could remember events from before his operation, then the problem must have been that consolidation had not taken place. Thus, the role of the hippocampal formation in memory is consolidation—converting short-term memories into long-term memories.

Spared Learning Abilities

H. M.’s and other patients with anterograde amnesia did not represent a total failure in learning ability.

They are capable of three of the four major types of learning described earlier: perceptual learning, stimulus–response learning, and motor learning.

1. Perceptual learning

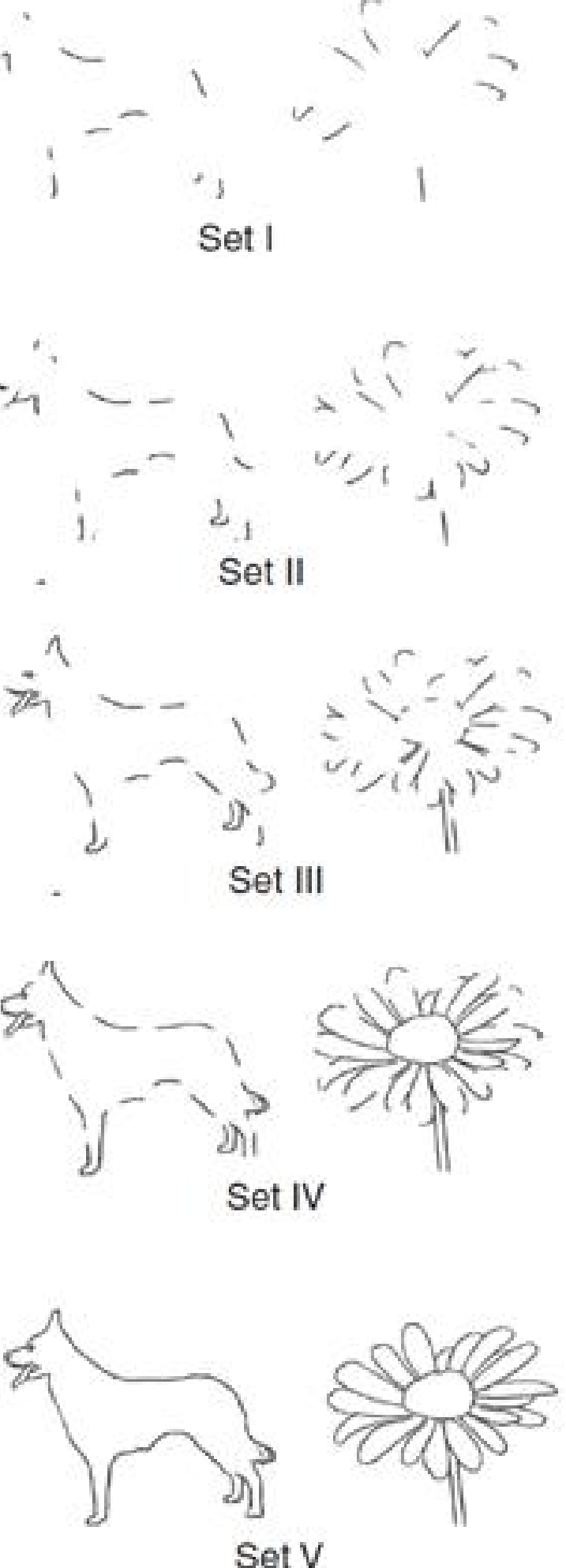

Examples of Broken Drawings

This figure shows two sample items from a test of the ability to recognize broken drawings; note how the drawings are successively more complete. Subjects are first shown the least complete set (set I) of each of twenty different drawings. If they do not recognize a figure (and most people do not recognize set I), they are shown more complete sets until they identify it. One hour later, the subjects are tested again for retention, starting with set I.

- Although H. M. learned to recognize the broken drawings, he denied that he had ever seen them before.

When H. M. was given this test and was retested an hour later, he showed considerable improvement (Milner, 1970). When he was retested four months later, he still showed this improvement.

His performance was not as good as that of normal control subjects, but he showed unmistakable evidence of long-term retention.

Johnson, Kim, and Risse (1985) found that patients with anterograde amnesia could learn to recognize faces and melodies.

- Although the amnesic patients in the study by Johnson, Kim, and Risse learned to like some of the Korean melodies better, they did not recognize that they had heard them before; nor did they remember having seen the pictures of the two young men.

The researchers played unfamiliar melodies from Korean songs to amnesic patients and found that when they were tested later, the patients preferred these melodies to ones they had not heard before.

The experimenters also presented photographs of two men along with stories of their lives: One man was said to be dishonest, mean, and vicious; the other was said to be nice enough to invite home to dinner. (Half of the patients heard that one of the men was the bad one, and the other half heard that the other man was.) Twenty days later, the amnesic patients said they liked the picture of the “nice” man better than that of the “nasty” one.

2. Stimulus–response learning

Investigators have also succeeded in demonstrating stimulus–response learning by H. M. and other amnesic subjects.

- Although H. M. successfully acquired a classically conditioned eyeblink response, he did not remember the experimenter, the apparatus, or the headband he wore that held the device that delivered a puff of air to his eye.

- Sidman, Stoddard, and Mohr (1968) successfully trained patient H. M. on an instrumental conditioning task—a visual discrimination task in which pennies were given for correct responses.

- In the experiment by Sidman, Stoddard, and Mohr, although H. M. learned to make the correct response (press a panel with a picture of a circle on it), he was unable to recall having done so. In fact, once H. M. had learned the task, the experimenters interrupted him, had him count his pennies (to distract him for a little while), and then asked him to say what he was supposed to do. He seemed puzzled by the question; he had absolutely no idea. But when they turned on the stimuli again, he immediately made the correct response.

For example, Woodruff-Pak (1993) found that H. M. and another patient with anterograde amnesia could acquire a classically conditioned eyeblink response. H. M. even showed retention of the task two years later: He acquired the response again in one-tenth the number of trials that were needed previously.

Sidman, Stoddard, and Mohr (1968) successfully trained patient H. M. on an instrumental conditioning task—a visual discrimination task in which pennies were given for correct responses.

3. Motor learning

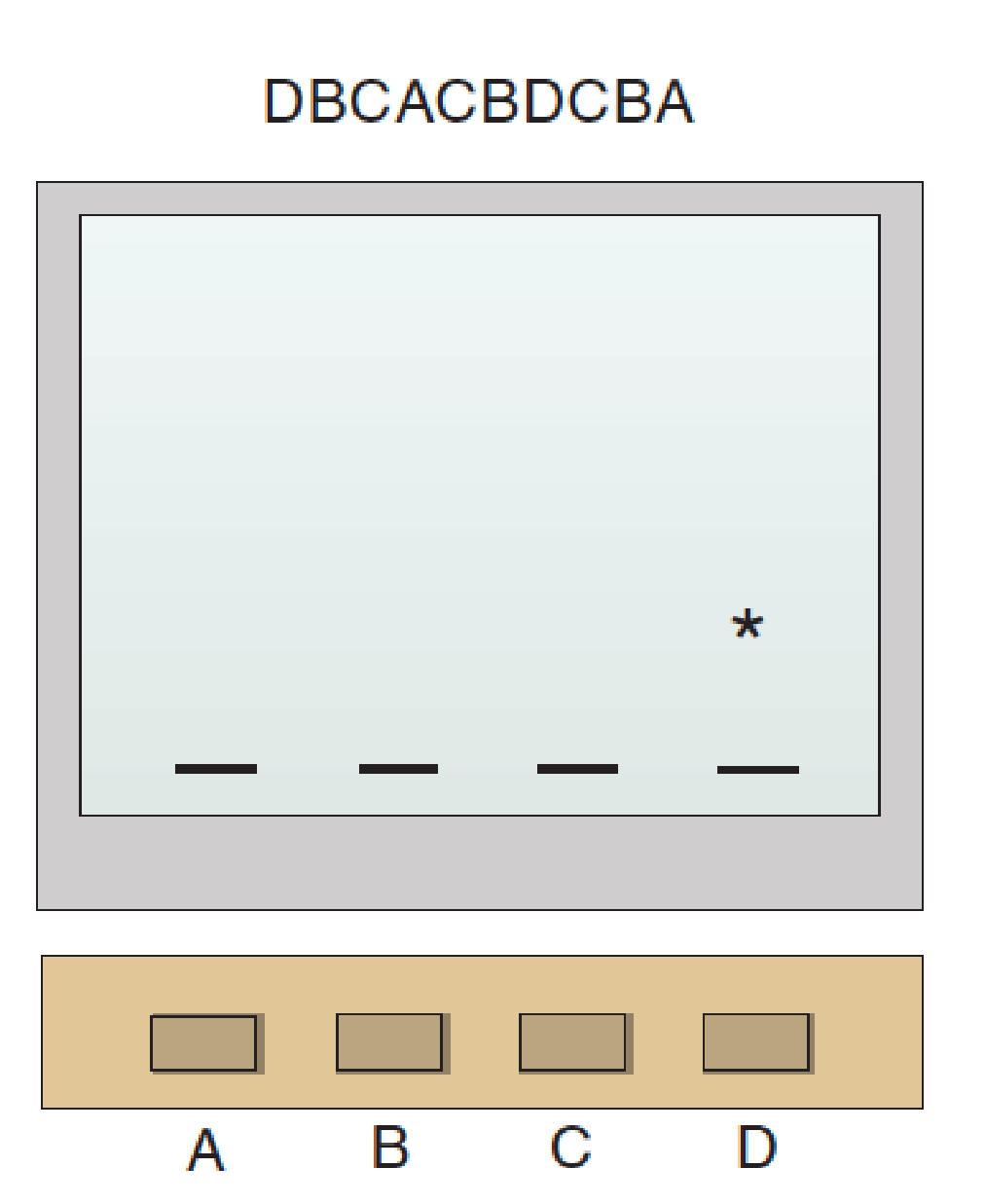

The Serial Reaction Time Task:

- In the procedure of the study by Reber and Squire (1998), subjects pressed the button in a sequence indicated by movement of the asterisk on the computer screen.

Finally, several studies have demonstrated motor learning in patients with anterograde amnesia. For example, Reber and Squire (1998) found that subjects with anterograde amnesia could learn a sequence of button presses in a serial reaction time task. They sat in front of a computer screen and watched an asterisk appear—apparently randomly—in one of four locations. Their task was to press the one button of the four that corresponded to the location of the asterisk. As soon as they did so, the asterisk moved to a new location, and they pressed the corresponding button.

Although experimenters did not say so, the sequence of button presses specified by the moving asterisk was not random. For example, it might be DBCACBDCBA, a ten-item sequence that is repeated continuously. With practice, subjects became faster and faster at this task. It is clear that their rate increased because they learned the sequence; if the sequence changed, their performance decreased. The amnesic subjects learned this task just as well as normal subjects did.

A study by Cavaco et al. (2004) tested amnesic patients on a variety of tasks modeled on real-world activities, such as weaving, tracing figures, operating a stick that controlled a video display, and pouring water into small jars. Both amnesic patients and normal subjects did poorly on these tasks at first, but their performance improved through practice. Thus, as you can see, patients with anterograde amnesia are capable of a variety of tasks that require perceptual learning, stimulus–response learning, and motor learning.

Finally, although the amnesic subjects in Reber and Squire’s study obviously learned the sequence of button presses, they were completely unaware that there was, in fact, a sequence; they thought that the movement of the asterisk was random..

Declarative and Nondeclarative Memories

Declarative Memories

If amnesic patients can learn tasks like these, you might ask, why do we call them amnesic?

The answer is this: Although the patients can learn to perform these tasks, they do not remember anything about having learned them.

They do not remember the experimenters, the room in which the training took place, the apparatus that was used, or any events that occurred during the training

- Learning to ride a bicycle is a combination of stimulus–response learning and motor learning, both of which are nondeclarative in nature. Remembering when we learned to ride a bike is an episodic memory, a form of relational learning.

The distinction between what people with anterograde amnesia can and cannot learn is obviously important because it reflects the basic organization of the learning process.

Clearly, there are at least two major categories of memories. Psychologists have given them several different names. For example, some investigators (Eichenbaum, Otto, and Cohen, 1992; Squire, 1992) suggest that patients with anterograde amnesia are unable to form declarative memories , which have been defined as those that are “explicitly available to conscious recollection as facts, events, or specific stimuli” (Squire, Shimamura, and Amaral, 1989, p. 218). The term declarative obviously comes from declare, which means “to proclaim; to announce.” The term reflects the fact that patients with anterograde amnesia cannot talk about experiences that they have had since the time of their brain damage. Thus, according to Squire and his colleagues, declarative memory is memory of events and facts that we can think and talk about.

Declarative memories are not simply verbal memories. For example, think about some event in your life, such as your last birthday. Think about where you were, when the event occurred, what other people were present, what events occurred, and so on. Although you could describe (“declare”) this episode in words, the memory itself would not be verbal. In fact, it would probably be more like a video clip running in your head: one whose starting and stopping points—and fast forwards and rewinds—you could control.

Nondeclarative memories

The other category of memories, often called nondeclarative memories , includes instances of perceptual, stimulus–response, and motor learning that we are not necessarily conscious of.

Some psychologists refer to these two categories as explicit and implicit memories, respectively.)

Nondeclarative memories appear to operate automatically. They do not require deliberate attempts on the part of the learner to memorize something. They do not seem to include facts or experiences; instead, they control behaviors. For example, think about when you learned to ride a bicycle. You did so quite consciously and developed declarative memories about your attempts: who helped you learn, where you rode, how you felt, how many times you fell, and so on. But you also formed nondeclarative stimulus–response and motor memories; you learned to ride. You learned to make automatic adjustments with your hands and body that kept your center of gravity above the wheels.

The acquisition of specific behaviors and skills is probably the most important form of implicit memory. Driving a car, turning the pages of a book, playing a musical instrument, dancing, throwing and catching a ball, sliding a chair backward as we get up from the dinner table—all of these skills involve coordination of movements with sensory information received from the environment and from our own moving body parts. We do not need to be able to describe these activities in order to perform them. We may not even be aware of all the movements we make while we are performing them.

Examples of Declarative and Nondeclarative Memory Tasks

| Declarative Memory Tasks |

|---|

| Remembering past experiences |

| Learning new words |

| Finding way in new environment |

| Nondeclarative Memory Tasks | Type of Learning |

|---|---|

| Broken drawings | Perceptual |

| Recognizing faces | Perceptual (and stimulus-response?) |

| Recognizing melodies | Perceptual |

| Classical conditioning (eye blink) | Stimulus–response |

| Instrumental conditioning (choose circle) | Stimulus–response |

| Sequence of button presses | Motor |

1. Anatomy of Anterograde Amnesia

One fact is clear: Damage to the hippocampus or to regions of the brain that supply its inputs and receive its outputs causes anterograde amnesia.

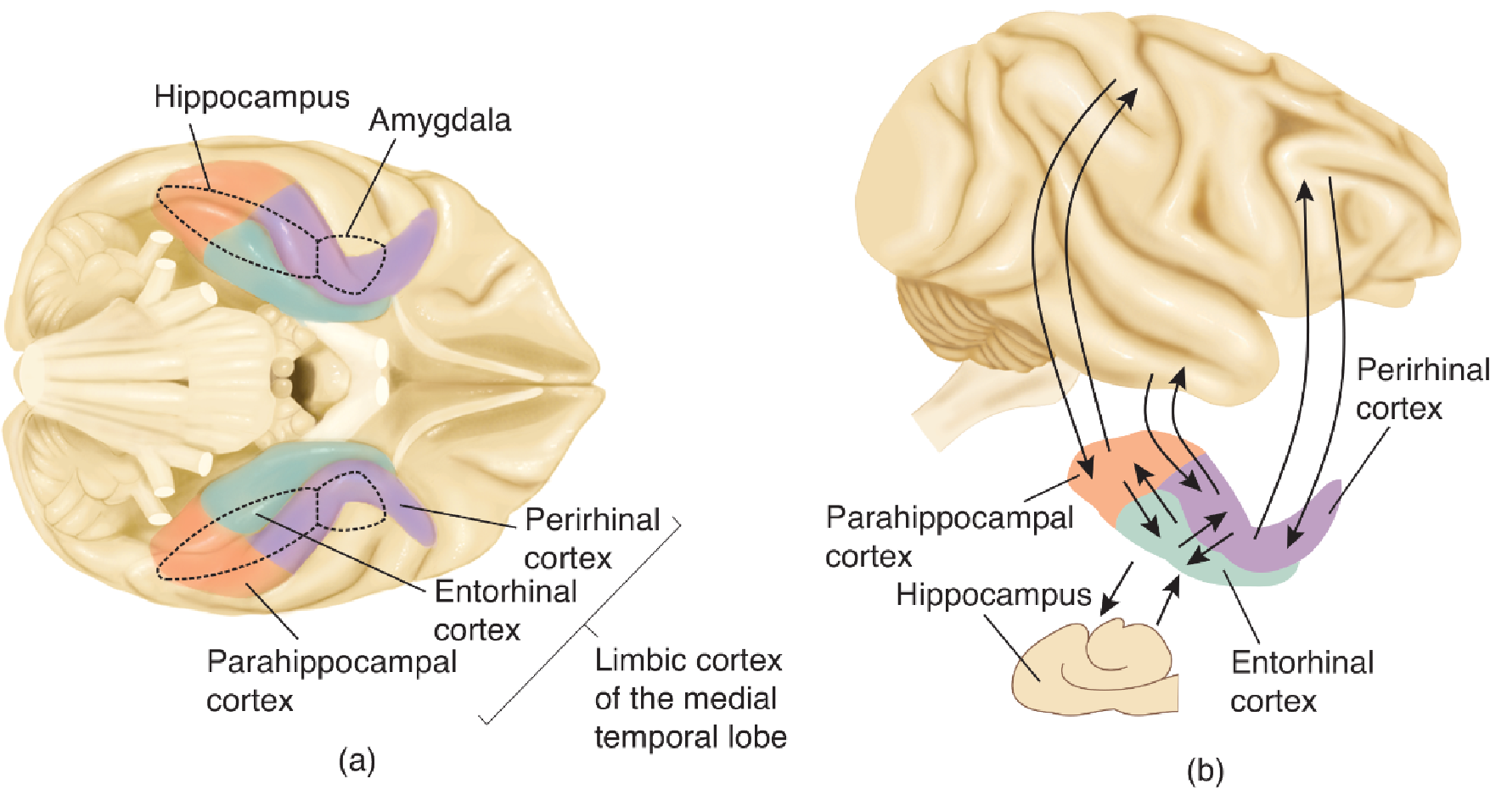

The hippocampal formation consists of the dentate gyrus, the CA fields of the hippocampus itself, and the subiculum (and its subregions). The most important input to the hippocampal formation is the entorhinal cortex; neurons there have axons that terminate in the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1.

The entorhinal cortex receives its inputs from the amygdala, various regions of the limbic cortex, and all association regions of the neocortex, either directly or via two adjacent regions of the limbic cortex: the perirhinal cortex and the parahippocampal cortex.

The outputs of the hippocampal system come primarily from field CA1 and the subiculum. Most of these outputs are relayed back through the entorhinal, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortex to the same regions of the association cortex that provide inputs.

2. Role of the Hippocampal Formation in Consolidation of Declarative Memories

The hippocampus receives information about what is going on from the sensory and motor association cortex and from some subcortical regions, such as the basal ganglia and amygdala.

t processes this information and then, through its efferent connections with these regions, modifies the memories that are being consolidated there, linking them together in ways that will permit us to remember the relationships among the elements of the memories—for example, the order in which events occurred, the context in which we perceived a particular item, and so on.

Without the hippocampal formation we would be left with individual, isolated memories without the linkage that makes it possible to remember—and think about—episodes and contexts.

3. Episodic and Semantic Memories

Declarative memories come in at least two forms: episodic and semantic.

- Episodic memories involve context; they include information about when and under what conditions a particular episode occurred and the order in which the events in the episode took place. Episodic memories are specific to a particular time and place, because a given episode—by definition—occurs only once.

- Semantic memories involve facts, but they do not include information about the context in which the facts were learned. In other words, semantic memories are less specific than episodic memories. For example, knowing that the sun is a star involves a less specific memory than being able to remember when, where, and from whom you learned this fact. Semantic memories can be acquired gradually, over time. Episodic memories, in contrast, must be learned all at once.

The symptoms of semantic dementia are quite different from those of anterograde amnesia. Semantic information is lost, but episodic memory for recent events can be spared.

The hippocampal formation and the limbic cortex of the medial temporal lobe appear to be involved in the consolidation and retrieval of declarative memories, both episodic and semantic, but the semantic memories themselves appear to be stored in the neocortex—in particular, in the neocortex of the anterolateral temporal lobe.

4. Spatial Memory

Patient H. M. has not been able to find his way around his present environment.

Although spatial information need not be declared (we can demonstrate our topographical memories by successfully getting from place to place), people with anterograde amnesia are unable to consolidate information about the location of rooms, corridors, buildings, roads, and other important items in their environment.

Bilateral medial temporal lobe lesions produce the most profound impairment in spatial memory, but significant deficits can be produced by damage that is limited to the right hemisphere.

For example, Luzzi et al. (2000) reported the case of a man with a lesion of the right parahippocampal gyrus who lost his ability to find his way around a new environment. The only way he could find his room was by counting doorways from the end of the hall or by seeing a red napkin that was located on top of his bedside table.

5. Relational Learning in Laboratory Animals

Hippocampal lesions disrupt the ability to keep track of and remember spatial locations. For example, H. M. never learned to find his way home when his parents moved after his surgery.

Laboratory animals show similar problems in navigation.

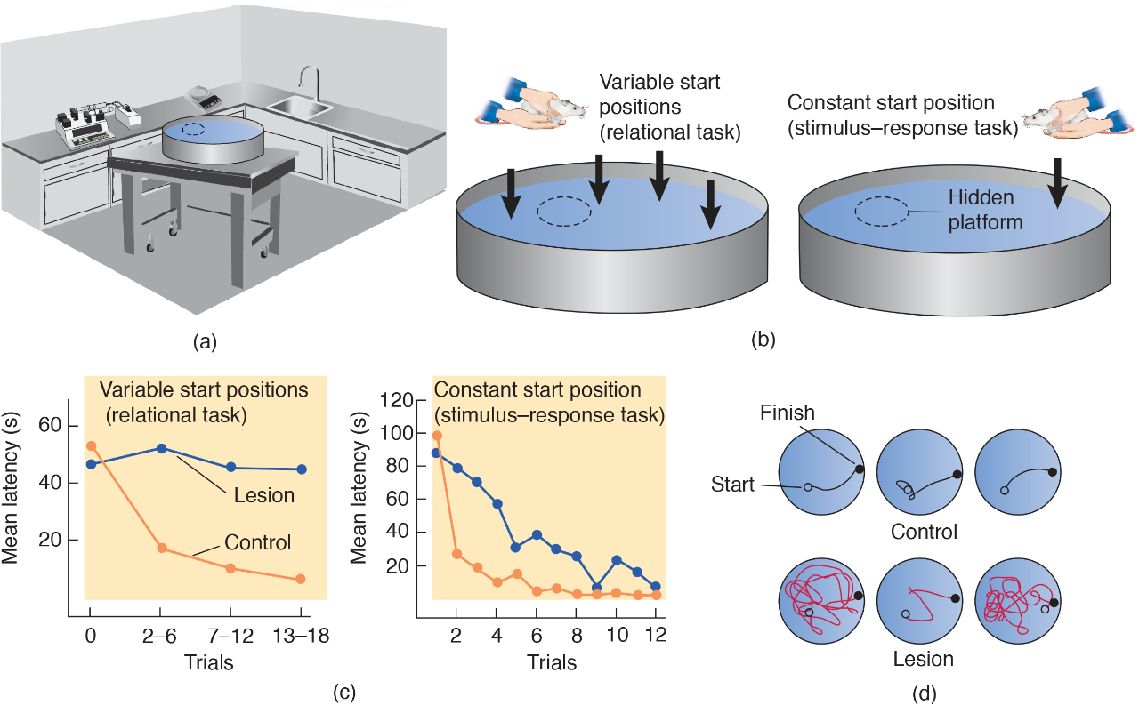

Morris et al. (1982) developed a task that has been adopted by other researchers as a standard test of rodents’ spatial abilities.

The Morris water maze requires relational learning; to navigate around the maze, the animals get their bearings from the relative locations of stimuli located outside the maze—furniture, windows, doors, and so on.

But the maze can be used for nonrelational, stimulus–response learning too. If the animals are always released at the same place, they learn to head in a particular direction—say, toward a particular landmark they can see above the wall of the maze (Eichenbaum, Stewart, and Morris, 1990).

The Morris Water Maze

- (a) Environmental cues present in the room provide information that permits the animals to orient themselves in space. (b) Variable and fixed start positions. Normally, rats are released from a different position on each trial. If they are released from the same position every time, the rats can learn to find the hidden platform through stimulus–response learning. (c) Performance of normal rats and rats with hippocampal lesions using variable or fixed start positions. Hippocampal lesions impair acquisition of the relational task. (d) Representative samples of the paths followed by normal rats and rats with hippocampal lesions on the relational task (variable start positions).

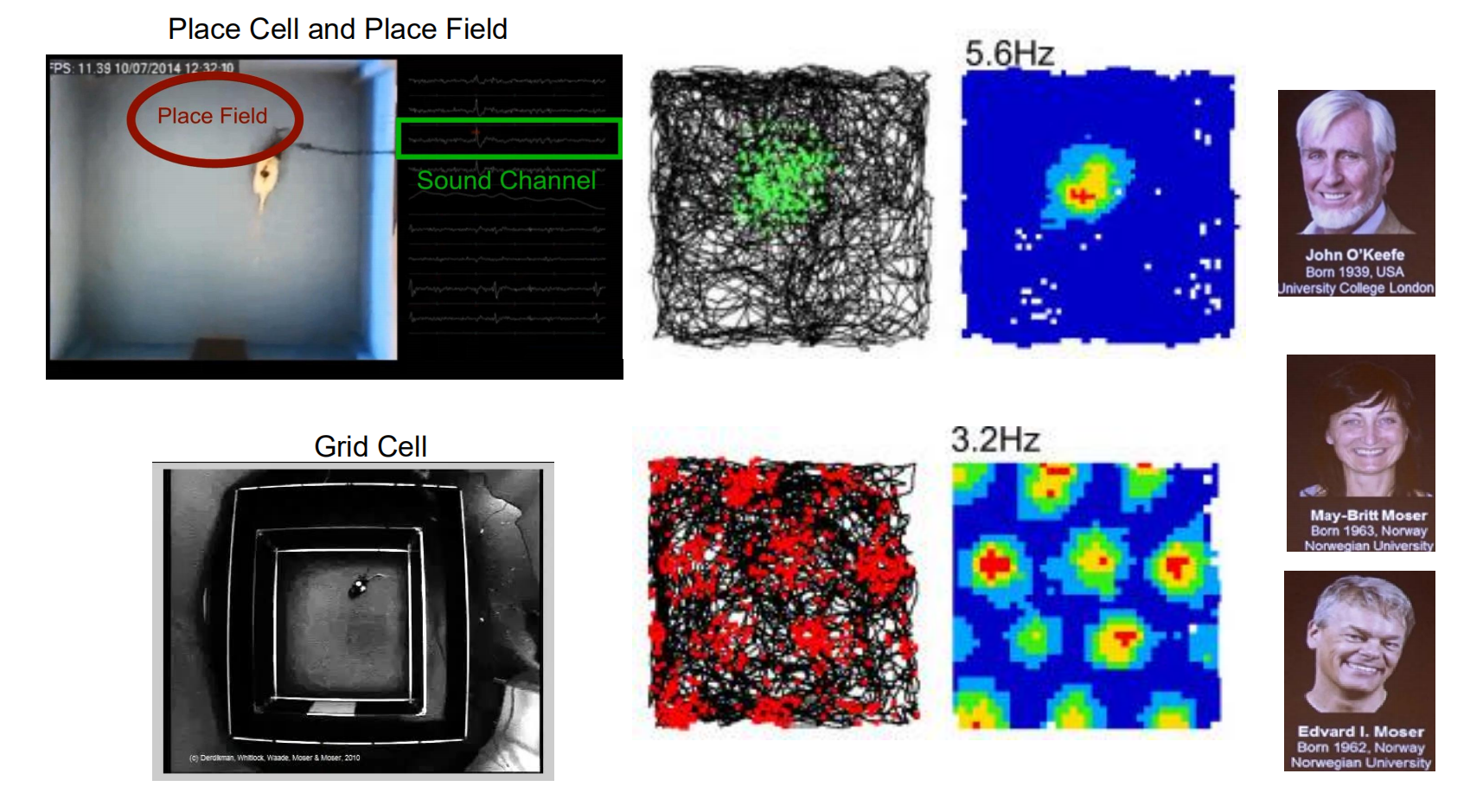

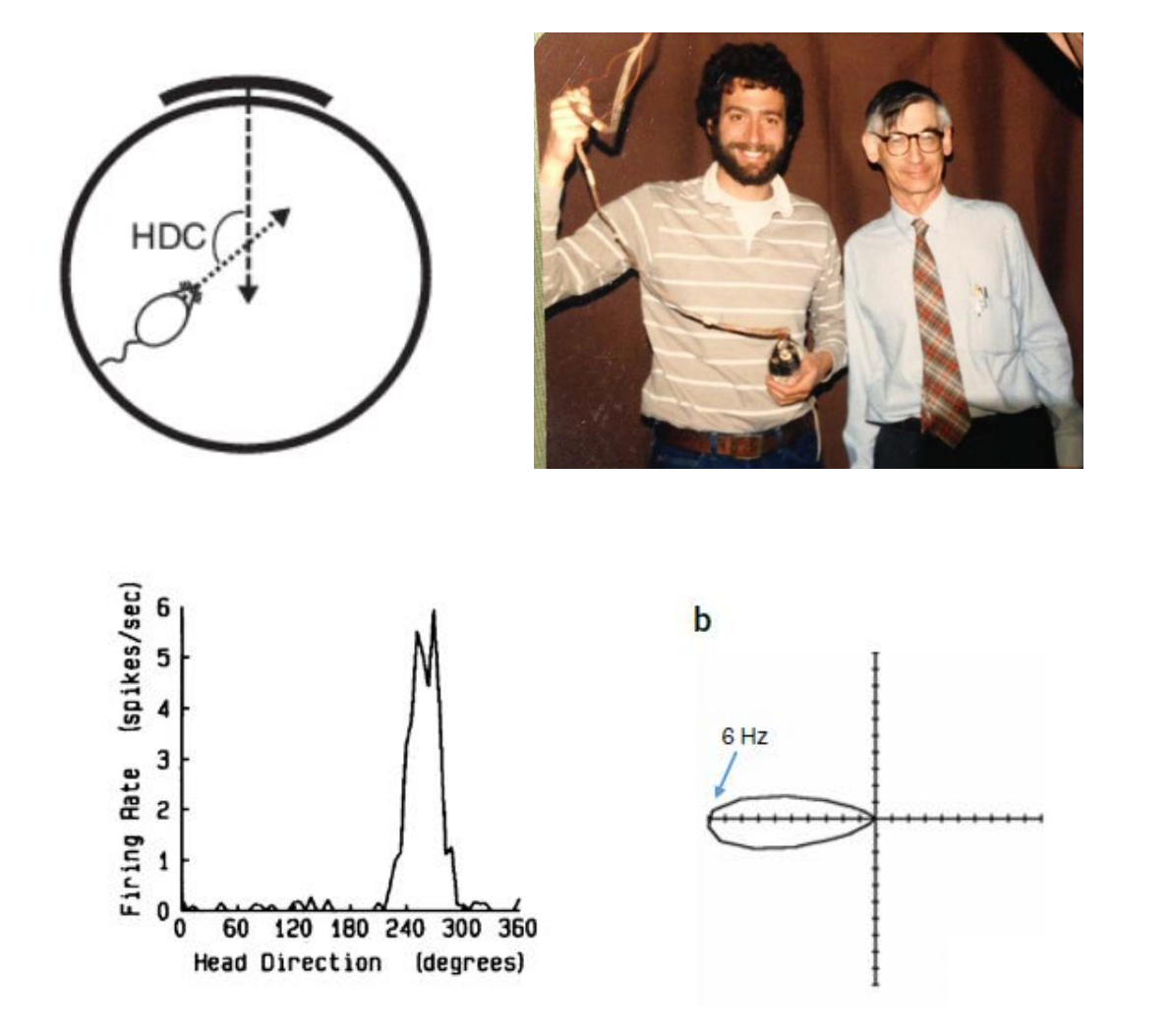

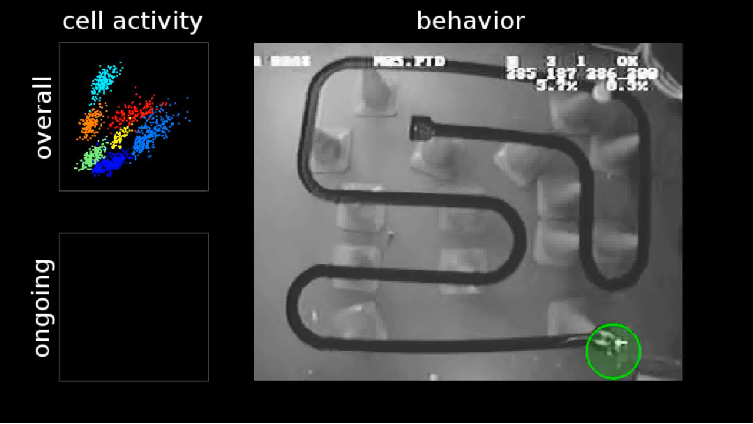

Place Cell and Grid Cell

Place cell

- A neuron that becomes active when the animal is in a particular location in the environment; most typically found in the hippocampal formation.

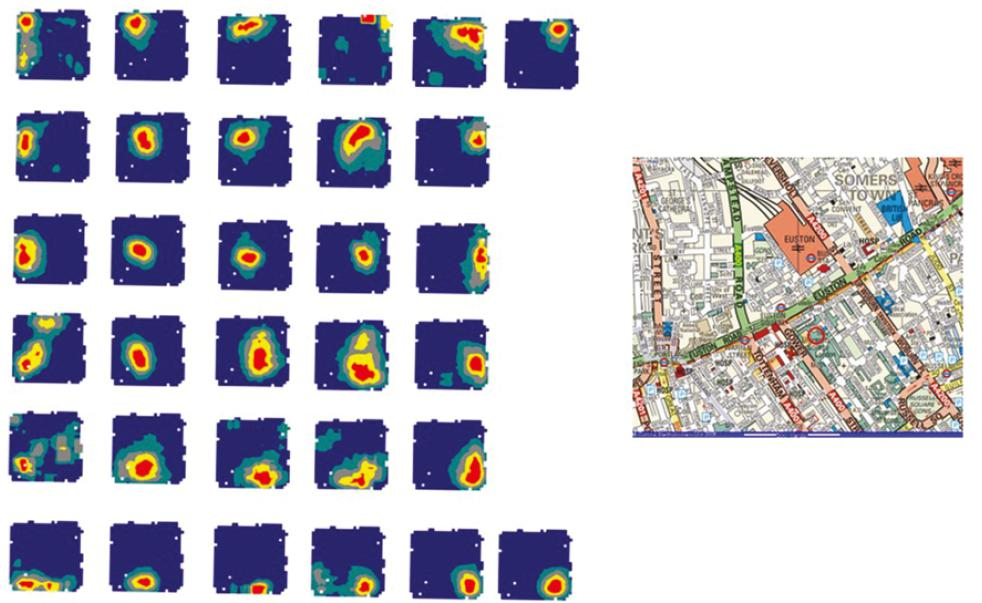

Place Cells and Cognitive maps

- Different place cells have different firing fields and 32 simultaneously-recorded place fields taken together cover the surface of an environment (McNaughton 1993)

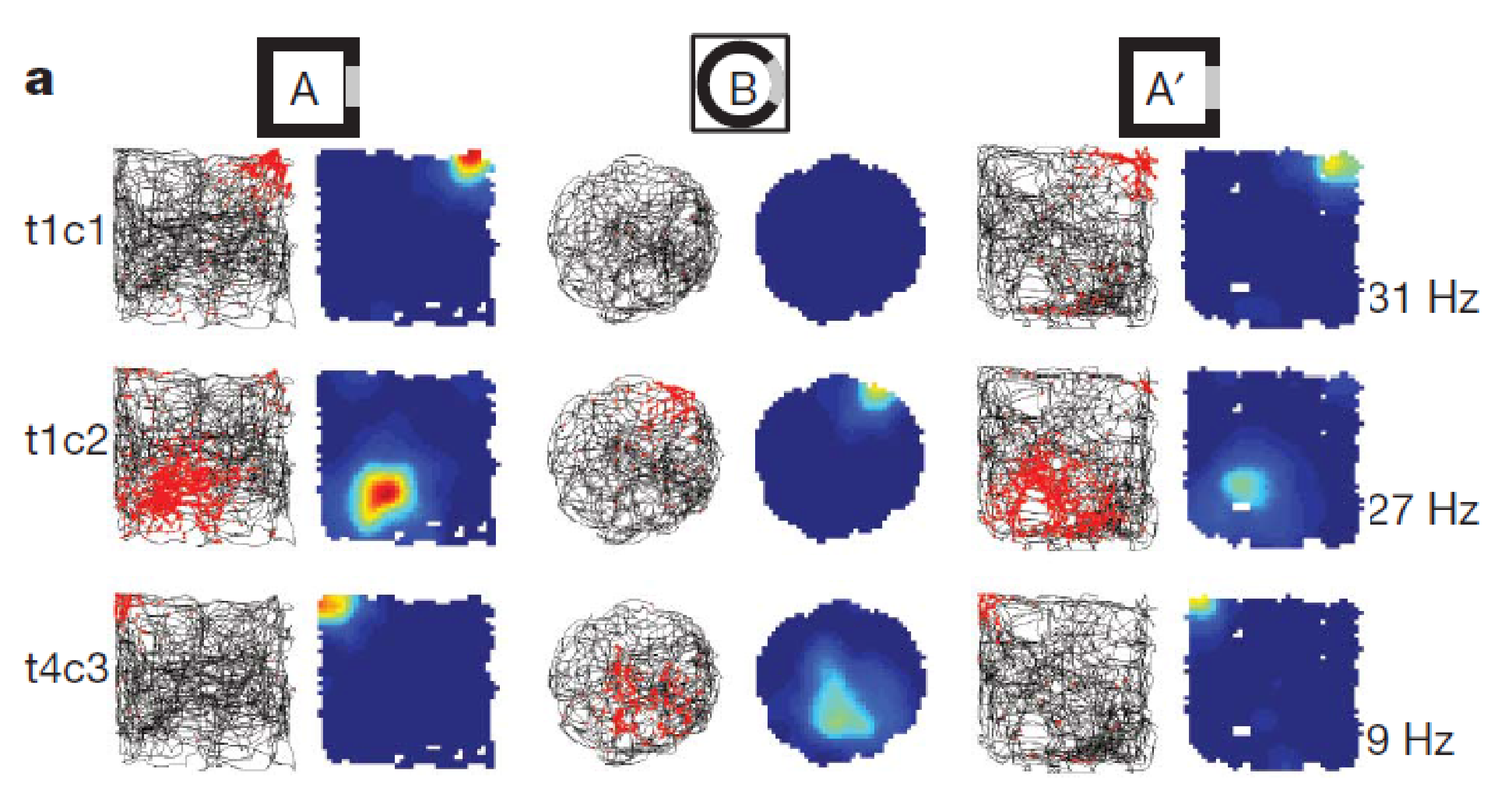

Remapping of place Cells

- Fyhn 2007 nature

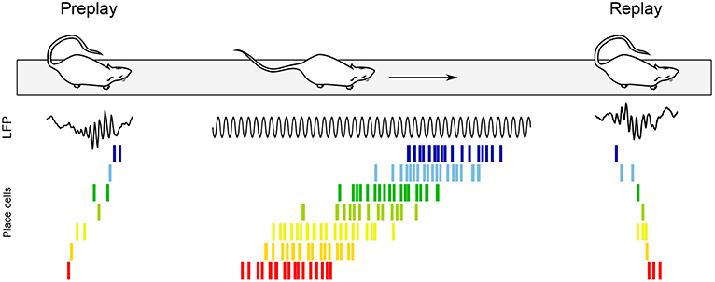

Head Direction cell

Replay of place Cells and memory consolidation

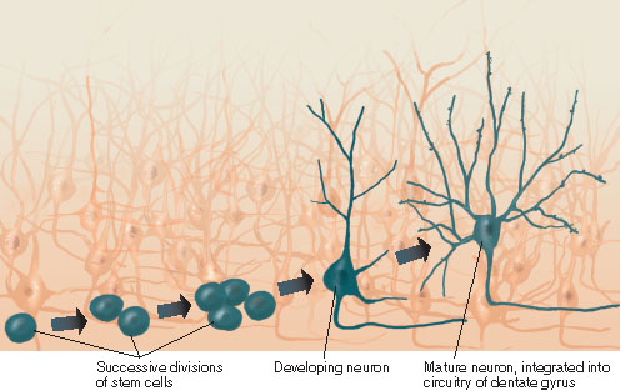

6. Role of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Consolidation