L16 Lipids And Membranes

一、The Molecular Structure and Behavior of Lipids

lipids are not generally water-soluble, due to the large portion of their structure that is hydrocarbon. This means that lipids are rarely found free in solution

Lipid molecules tend to be insoluble in water, but they can associate to form water-soluble structures such as:

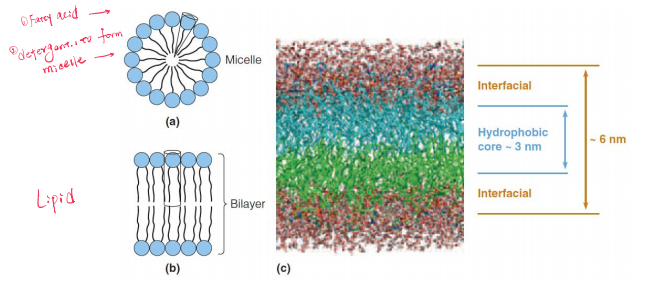

- Micelles 胶束 ( the hydrocarbon tails cluster together within the structure and the carboxylate heads are in contact with the surrounding water)

- Vesicles 囊泡

- Bilayers 双分子层(膜)

Membrane lipids are amphipathic.

They tend to form surface monolayers, bilayers, micelles, or vesicles when in contact with water

If fatty acids are mixed with water and an oily or greasy substance (for example, a hydrocarbon), the micelles will form around the oil droplets, emulsifying them. In this way soaps and synthetic detergents solubilize grease.

Unlike the amino acids in proteins, the nucleotides in nucleic acids, and the monosaccharides in complex carbohydrates, lipids do not form large covalent polymers. Rather, they tend to associate with each other through noncovalent forces.

Because the weak interactions (hydrophobic forces), the lipid can stick together, that is why lipid is considered a macromolecule

Just as nonpolar groups in proteins associate via an entropy-driven hydrophobiceffect, so do the nonpolar tails of lipids.

A second stabilizing force comes from the van der Waals interactions between the hydrocarbon regions of the molecules.

Fatty Acids 脂肪酸

1. Introduction

The simplest lipids are the fatty acids.

The simplest lipids are the fatty acids, which are also constituents of many more complex lipids.

Their basic structure is a hydrophilic carboxylate group attached to one end of a hydrocarbon chain, which contains typically 12 to 24 carbons.

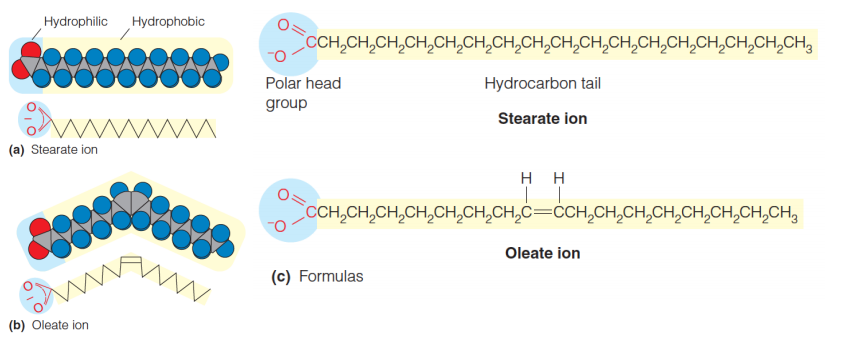

An example is stearic acid,(化]硬脂酸;[化]十八酸) a C-18 fatty acid.

Stearic acid is an example of a saturated fatty acid(饱和脂肪酸), one in which the carbons of the tail are all saturated with hydrogen atoms

Many important naturally occurring fatty acids are unsaturated, that is, they contain one or more double bonds.

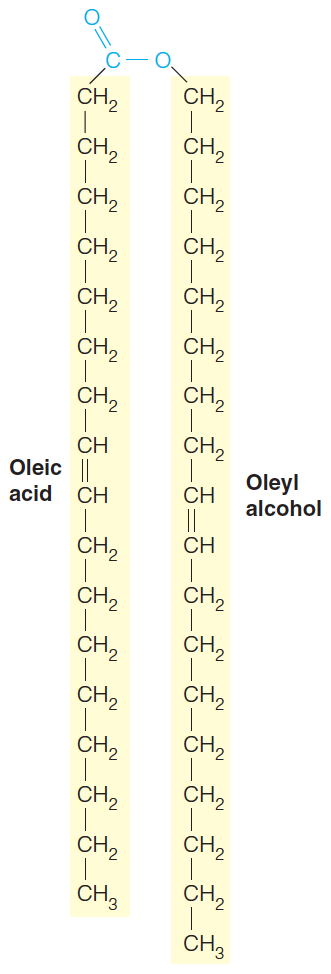

An example is *oleic acid,*(十八烯酸,油酸) a C-18 $\Delta ^{9}$ fatty acid

Plant oil 大部分是不饱和脂肪酸

If double bonds are present (unsaturation), they are usually cis.

Naturally occurring unsaturated fatty acids, the orientation about double bonds is cis rather than trans.

cis is more stable, for it has lower melting temperature ($T_{m}$)

Most naturally occurring fatty acids contain an even number of carbon atoms.

Most of the naturally occurring fatty acids have an even number of carbon atoms because they are synthesized by sequential additions of a two-carbon precursor (see Chapter 17).

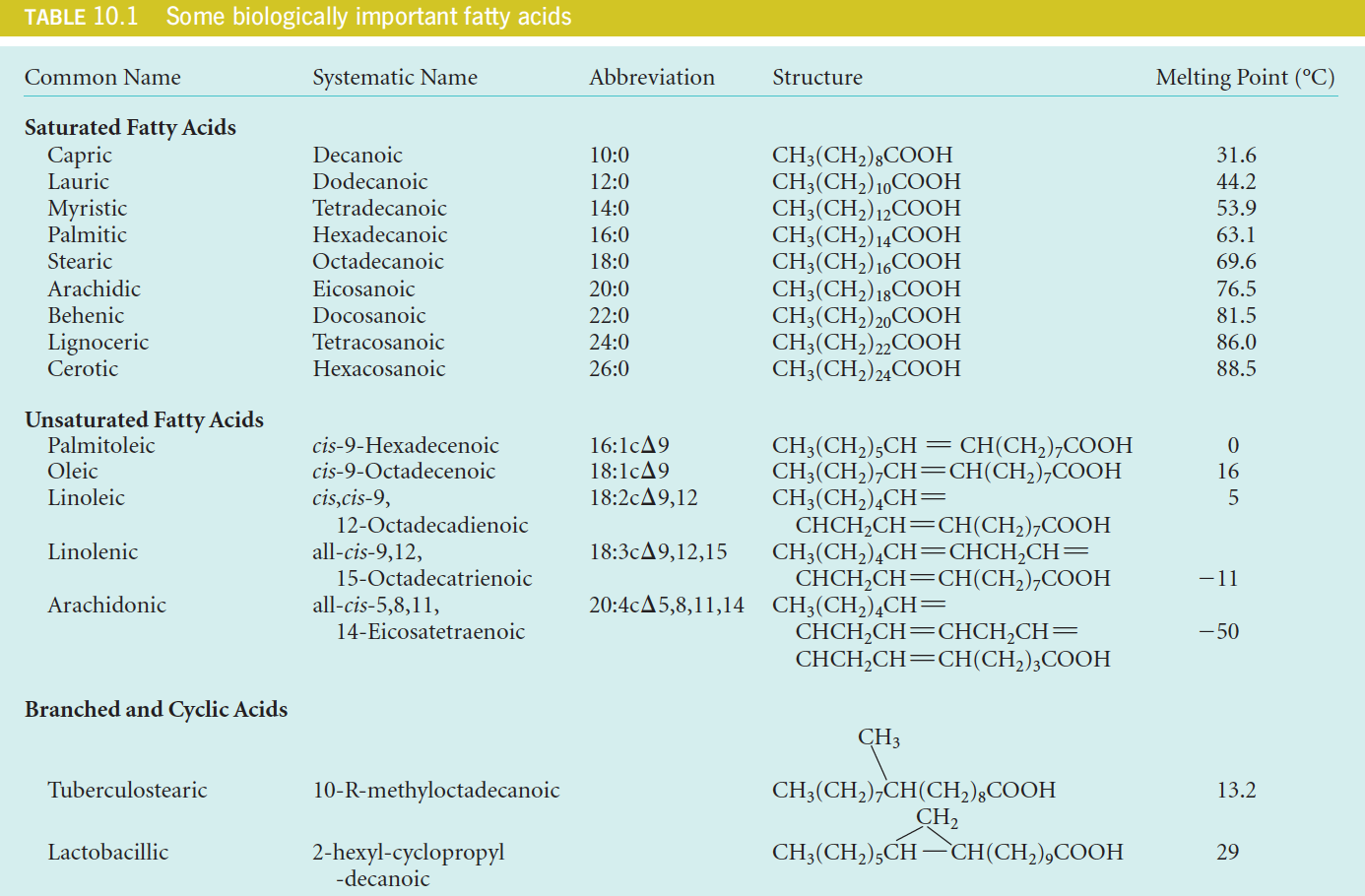

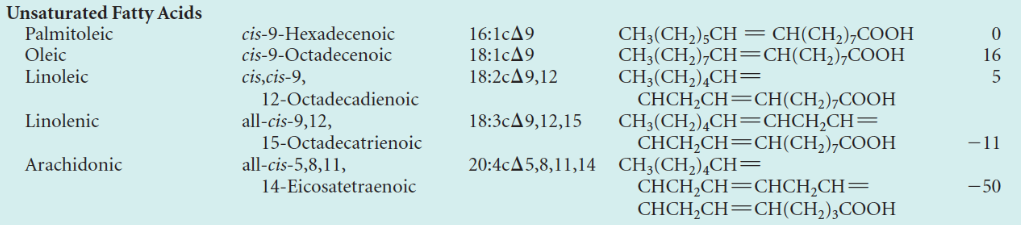

Although the hydrocarbon chains are linear in most fattyacids, some fatty acids (found primarily in bacteria) contain branches or even cyclic structures (Table 10.1).

2. A System of Abbreviations For Fatty Acids

It is illustrated in Table 10.1. The rules are as follows:

- The number before the colon (冒号) gives the total number of carbons,

- and the number after the colon gives the count of double bonds.

- The configurations and positions of double bonds are indicated by c (cis) or t (trans) followed by $\Delta$ and one or more numbers.

- These numbers denote the carbon atom (the carboxylic carbon is designated as “1”) where each double bond starts.

Thus, oleic acid is designated by $18:1c \Delta 9$ and linolenic by $18:3c \Delta 9,12,15$

3. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA)

Animals generally do not produce via biosynthesis all the PUFAs they need for proper cellular function; thus, these fatty acids must be part of their diet.

Fats

The long hydrocarbon chains of fatty acids are extraordinarily efficient for energy storage because they contain carbon in a reduced form and will therefore yield a large amount of energy on oxidation.

Because they are hydrophobic, fat stores are also anhydrous (无水的(尤指结晶水)), whereas glycogen is hydrated (含水的,与水结合的).

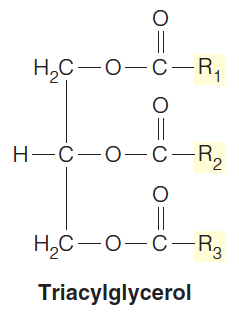

Fats, or triacylglycerols (三酰基甘油), are triesters of fatty acids and glycerol.

They are the major long-term energy storage molecules in many organisms.

Triacylglycerols with the same fatty acid esterified at each position are called “simple fats.” Most triacylglycerols, however, are “mixed fats” that contain a mixture of fatty acids

1. Fats In Animals

Fat storage in animals serves three distinct functions:

1.Energy production - most fat in most animals is oxidized for the generation of ATP, to drive metabolic processes.

2.Heat production - specialized cells (in “brown fat” of warm-blooded animals, for example) oxidize triacylglycerols for heat production, rather than to make ATP.

3.Insulation - in animals that live in a cold environment, layers of fat cells under the skin serve as thermal insulation. The blubber of whales is one obvious example.

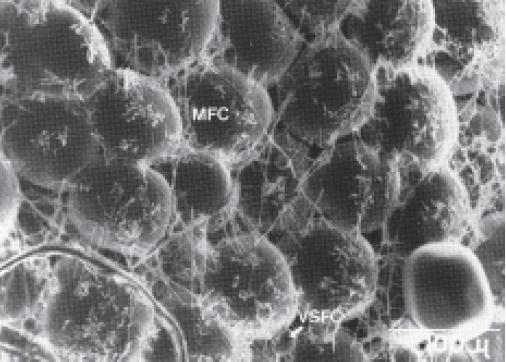

Adipocytes(脂肪细胞) (animal fat storage cells)make up a large part of adipose tissue.

The designations MFC and VSFC correspond to “mature fat cell” and “very small fat cell,” respectively.

2. Soap and Detergents

Soap

When fats are hydrolyzed with strong bases such as NaOH or KOH (in earlier times, wood ashes were used), a soap is produced*.*

This process is called saponification.(皂化)

The fatty acids are released as either sodium or potassium salts, which are fully ionized.

However, as cleansers, soaps have the disadvantage that the fatty acids are precipitated(沉淀) by the calcium or magnesium ions present in “hard” water, forming a scum(浮渣;泡沫;糟粕) and destroying the emulsifying action(乳化作用).

Detergents 洗涤剂

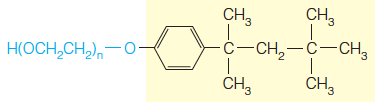

Synthetic detergents have been devised that do not have this defect.

One class is exemplified by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS): $NaO_{3} SO(CH_{2}){11}CH{3}$

The salts of dodecyl sulfate with divalent cations (i.e., Ca2+ and Mg2+) are more soluble.

Recall that SDS is widely used in forming micelles about proteins for gel electrophoresis.

There are also synthetic nonionic detergents, like Triton X-100:

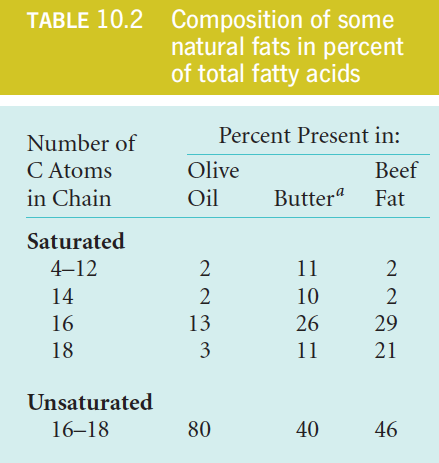

3. Saturated And Unsaturated Fat

Characteristics

Fats rich in unsaturated fatty acids (like olive oil) are liquid at room temperature, whereas those with a higher content of saturated fatty acids (like butter) are more solid.

Reason

Long saturated chains can pack closely together, thereby increasing the number of van der Waals contacts to form regular, semi-crystalline structures.

In contrast, the kind of bend imposed by one or more cis double bonds (see Figure 10.1b) makes molecular packing less regular, and therefore more dynamic. (Lower $T_{m} $)

Indeed, partial hydrogenation of unsaturated fat oils (like corn oil) is used commercially to convert them to firmer fats,

Oxidative cleavage of the double bonds in fats yields volatile aldehydes and carboxylic acids, which contribute to the rancid odor of spoiled fats.

Hydrogenation reduces such bonds to single bonds, but it also converts some cis double bonds to trans double bonds, yielding so-called trans fats.

Because trans fats have been associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, the FDA requires food packaging to list the content of trans fats and several cities have banned use of trans fats for cooking in restaurants.

Wax

1. Structure of a typical wax

Waxes are formed by esterification( 酯化作用) of fatty acids and long-chain alcohols.

Esterification with glycerol diminishes the hydrophilic character of the head groups of the fatty acids. As a consequence, triacylglycerols are water-insoluble.

Fats accumulated in plant and animal cells therefore form as oily droplets in the cytoplasm

In the natural waxes, a long-chain fatty acid is esterified to a long-chain alcohol (Figure 10.4).

The small head group can contribute little hydrophilicity, in contrast to the significant hydrophobic contribution of the two long tails. Thus, the waxes are completely water insoluble.

Often serve as water repellents(排斥剂), as in the feathers of some birds and the leaves of some plants.

2. Functions

In some marine microorganisms, waxes are used instead of other lipids for energy storage.

In beeswax, they serve a structural function.

As with the triacylglycerols(三酰基甘油), the firmness of waxes increases with chain length and degree of hydrocarbon saturation

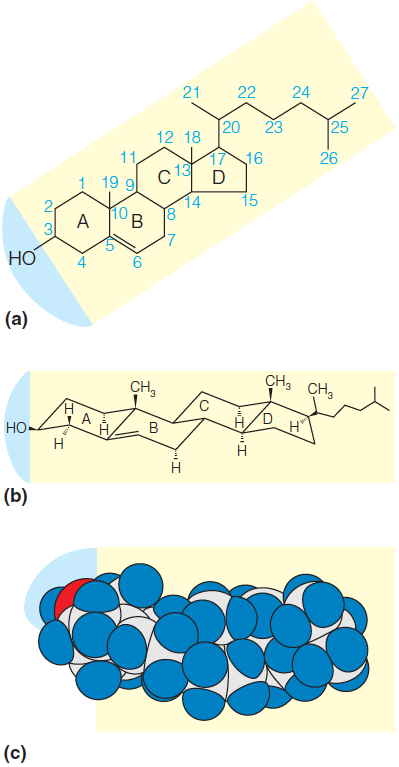

Phospholipids and membrane structure:

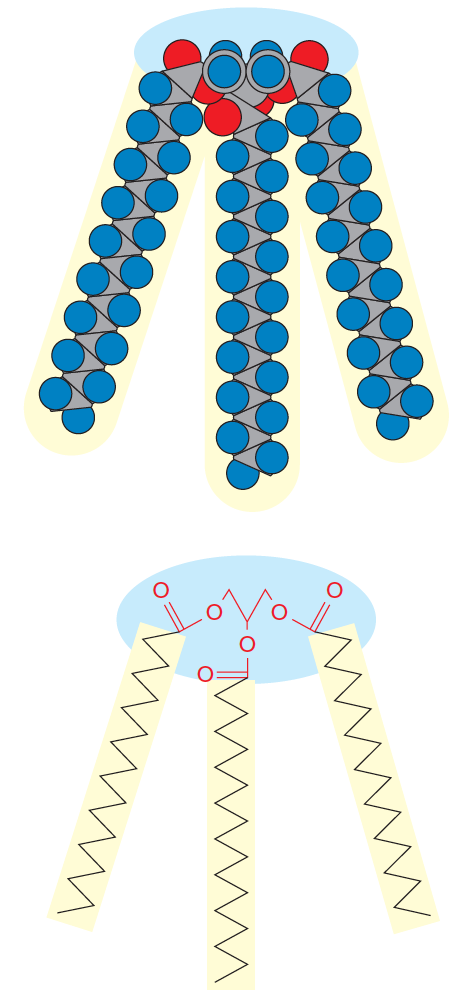

Fatty acids are wedge-shaped and tend to form spherical micelles.

If a large head group is attached to a single hydrocarbon chain, the molecule is wedge-shaped and will tend to form spherical micelles

Phospholipids are more cylindrical and pack together to form a bilayer structure.

A computer simulation of a phospholipid bilayer.

A double tail yields a roughly cylindrical molecule (Figure 10.5b); such cylindrical molecules can easily pack in parallel to form extended sheets of bilayer membranes with the hydrophilic head groups facing outward into the aqueous regions on either side. (Figure 10.5c)

Glycerophospholipids 甘油磷脂

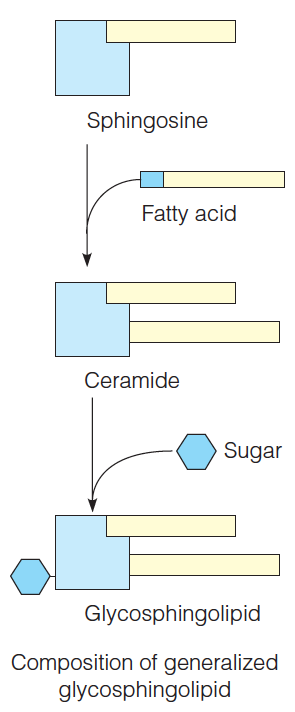

Sphingolipids 鞘脂

Glycosphingolipids 糖鞘脂

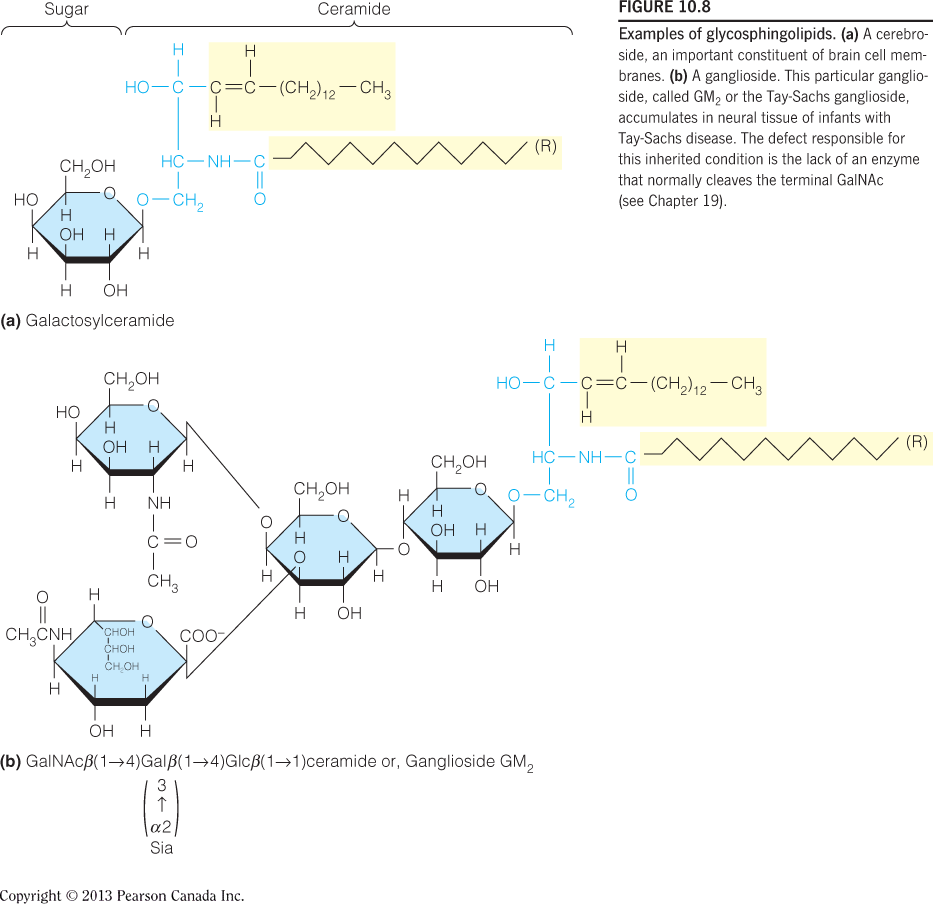

Glycoglycerolipids 甘油糖脂

Their structure is that of a large head group attached to a double tail yielding a roughly cylindrical molecule.

Such cylindrical molecules can easily pack in parallel to form extended sheets of bilayer membranes with the hydrophilic head groups facing outward into the aqueous regions on either side.

They differ principally in the nature of the head group.

The bilayer is roughly 6 nm thick, with ~1.5 nm of interface on either side of the ~3 nm hydrophobic core.

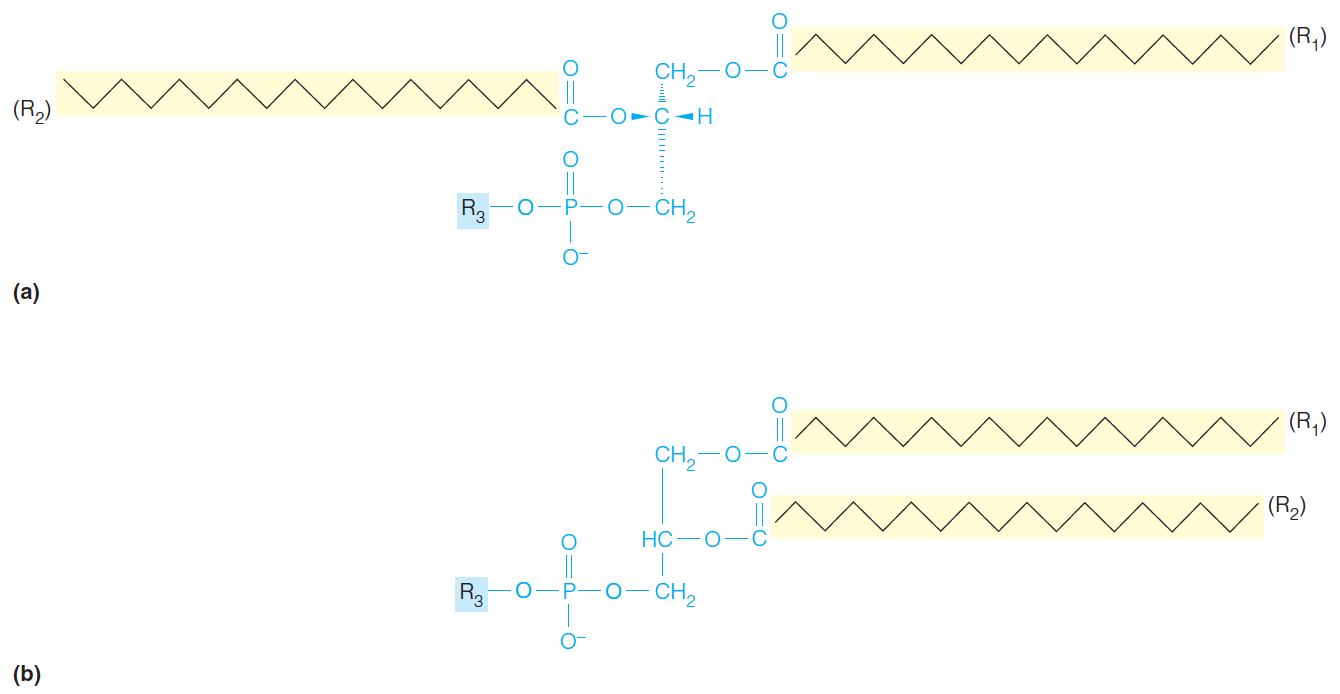

Glycerophospholipid 甘油磷脂

1. Structures

Stereochemical view of a generalized glycerophospholipid.

The same structure represented in the convention used in this text, with hydrophobic groups to the right, hydrophilic to the left.

Typically, the groups $R_{1}$ and $R_{2}$ are acyl side chains derived from the fatty acids; $R_{1}$ often is saturated, and $R_{2}$ is unsaturated. The hydrophilic $R_{3}$ head group varies greatly, and confers the greatest variation in properties among the glycerophospholipids.

- R3 is a hydrophilic group

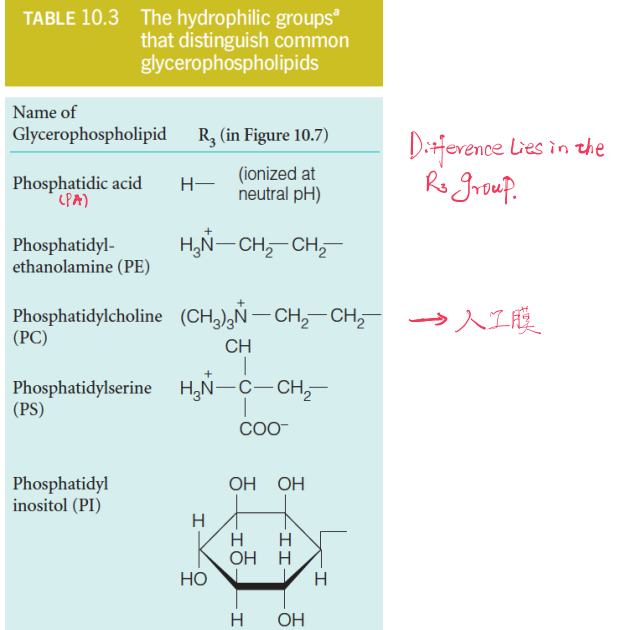

2. Some Hydrophilic Groups

| Name of glycerophospholipid | Translation |

|---|---|

| Phosphatidic acid (PA) | 磷脂酸 |

| Phosphatidyl-ethanolamine (PE) | 磷脂酰乙醇胺 |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | 磷脂酰胆碱(卵磷脂),常用于人工膜 |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | 磷脂酰丝氨酸 |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | 磷脂酰肌醇 |

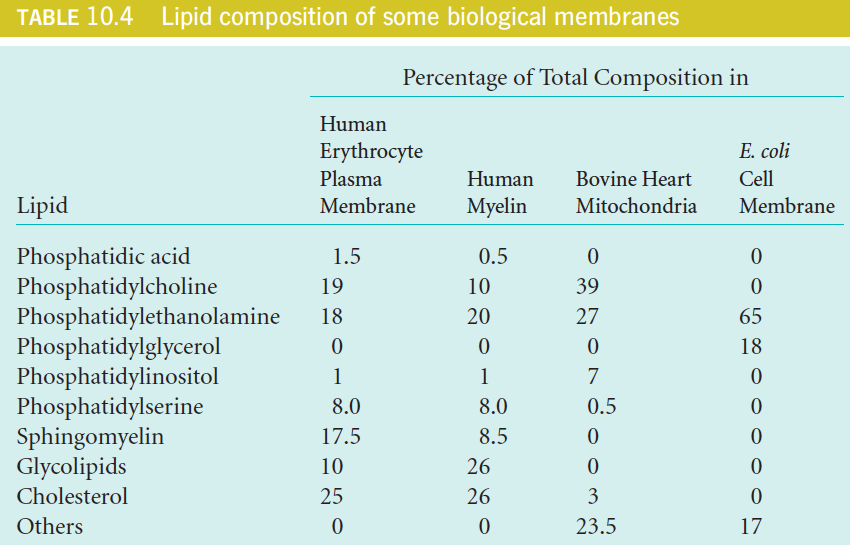

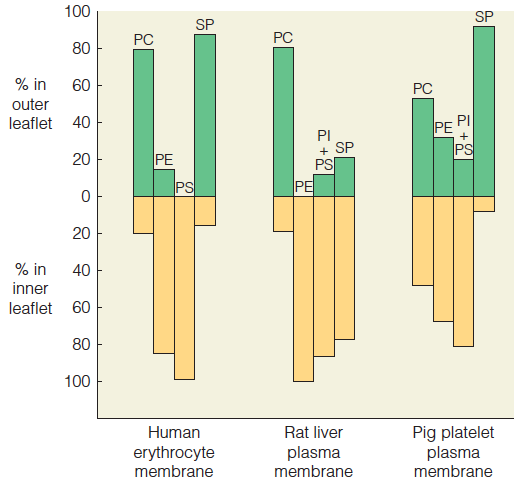

3. Lipid composition of some biological membranes

Sphingolipid and Glycosphingolipids

1. Sphingolipid

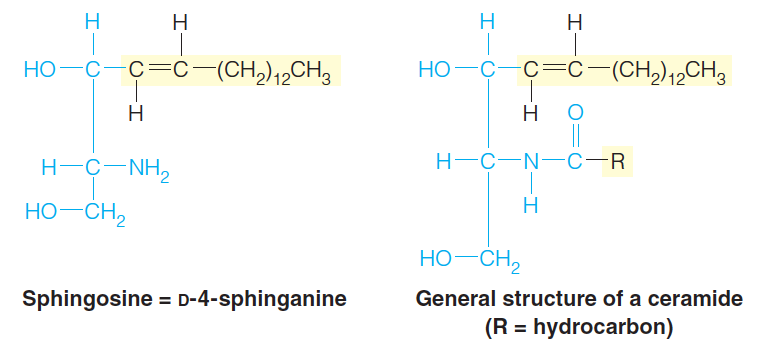

A second major class of membrane constituents is built on the amino alcohol sphingosine, rather than on glycerol.

The structure of sphingosine includes a long-chain hydrophobic tail, so it requires the addition of only one fatty acid to make it suitable as a membrane lipid.

If a fatty acid is linked via an amide bond to the NH2 group, the class of sphingolipids referred to as ceramides(神经酰胺) is obtained:

Ceramides consist of sphingosine and a fatty acid

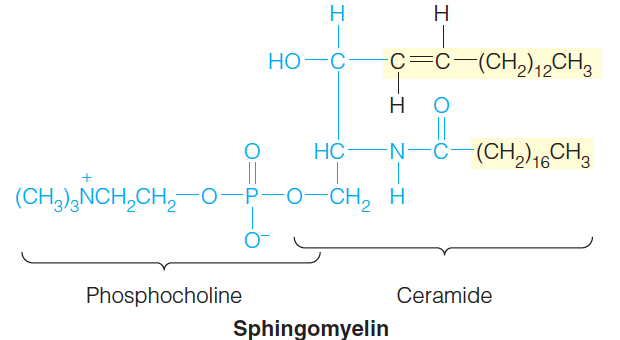

An especially important example is sphingomyelin ((神经)鞘磷脂), in which a phosphocholine (胆碱磷酸) group is attached to the C-3 hydroxyl.

2. Glycosphingolipid

Examples of glycosphingolipids:

A cerebroside(脑苷脂) - an important constituent of brain cell membranes.

A ganglioside(神经节苷脂) - This particular ganglioside, called $GM_{2}$ or the Tay-Sachs ganglioside, accumulates in neural tissue of infants with Tay-Sachs disease. The defect responsible for enzyme that normally cleaves the terminal GalNAc.

Glycoglycerolipids 甘油糖脂

Another class of lipids, less common in animal membranes but widespread in plant and bacterial membranes, are the glycoglycerolipids, exemplified by monogalactosyl diglyceride:

This compound may actually be the most abundant of all polar lipids, for it constitutes about half the lipid in chloroplast membranes (see Chapter 16). Such lipids are also abundant in archaea, where they are the major membrane components.

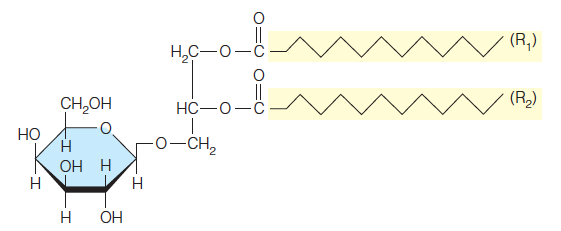

Cholesterol 胆固醇

Cholesterol is a member of a large group of substances called steroids, which include a number of important hormones, among them the sex hormones of higher animals. In fact, cholesterol is the precursor for many of these substances

Cholesterol, is a component of many animal membranes.

It influences membrane fluidity(膜流动性) by its bulky structure.

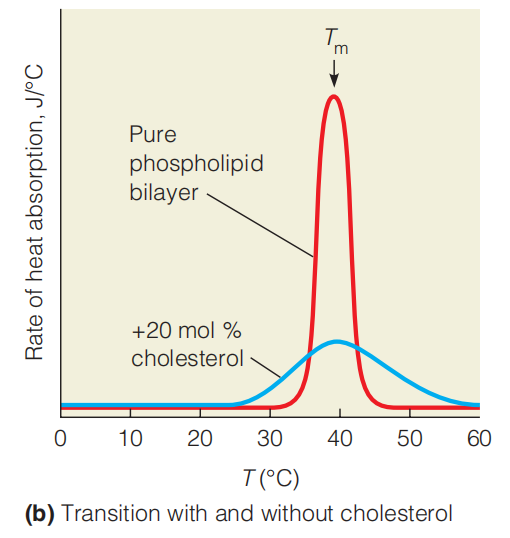

Cholesterol has a specific and complex effect on membrane fluidity. As Figure 10.12b shows for a synthetic membrane, cholesterol does not influence the transition temperature markedly, but it does broaden the transition.

The effects of cholesterol on membrane structure are strongly dependent on its concentration in the membrane.

Cholesterol is a weakly amphipathic substance because of the hydroxyl group at one end of the molecule.

As the conformational structure in Figure 10.9b shows, the fused cyclohexane rings in cholesterol are all in the chair conformation.

This makes cholesterol a bulky, rigid structure as compared with other hydrophobic membrane components such as the fatty acid tails; thus, the cholesterol molecule tends to disrupt regular packing of fatty acid tails in membrane structure.

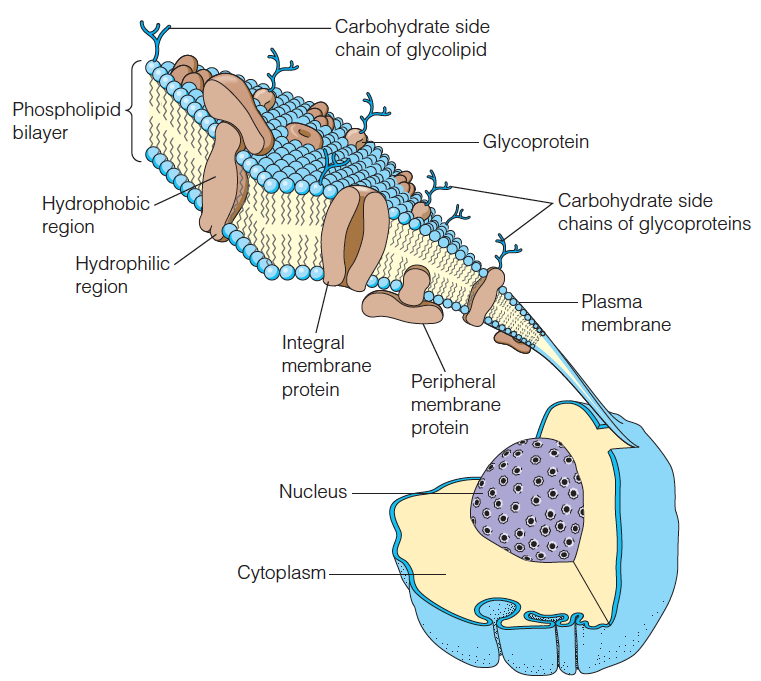

三、The Structure and Properties of Membranes and Membrane Proteins

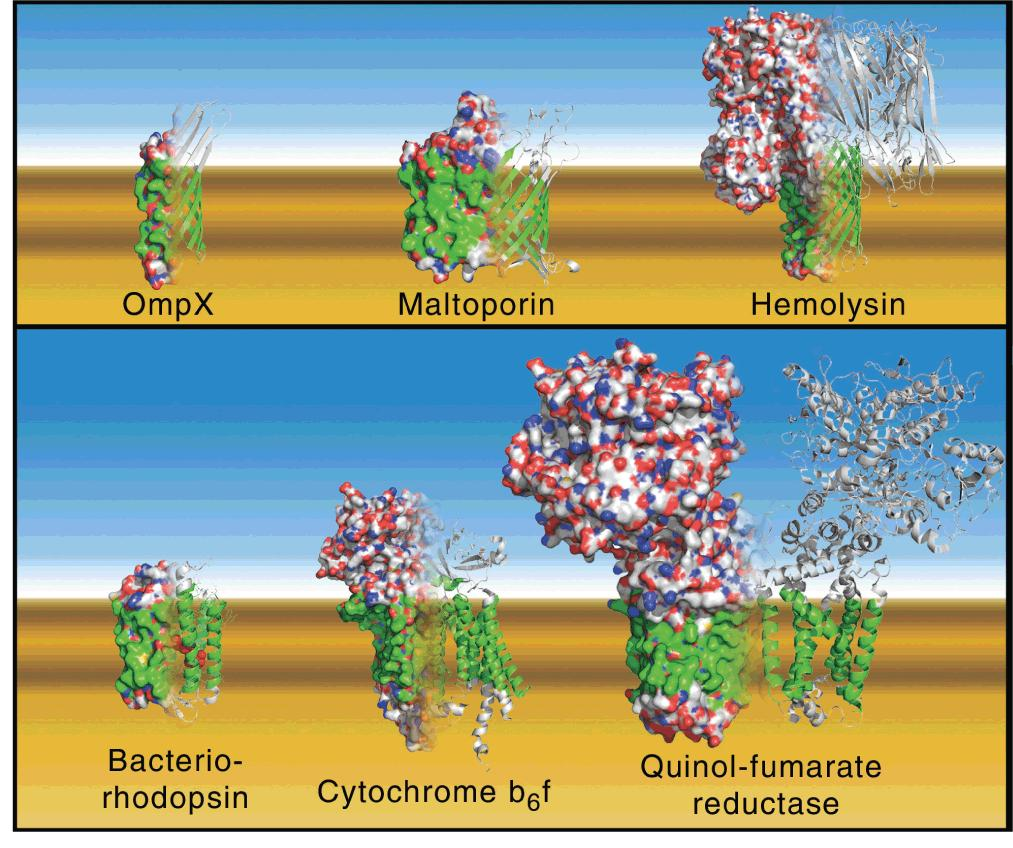

An important feature of cellular membranes is the wide variety of specific proteins contained within the lipid bilayer or bound to its surface.

Fluid Mosaic Model And Membrane Proteins

Much of our current understanding concerning biological membranes is based upon the fluid mosaic model proposed by S. J. Singer and G. L. Nicolson in 1972.

A membrane is a fluid mixture of lipids and proteins.

Peripheral membrane proteins are associated with one side of the bilayer and can be separated from the membrane without disrupting the bilayer.

Integral membrane proteins are more deeply embedded in the bilayer and can only be extracted under conditions that disrupt membrane structure.

Many integral membrane proteins extend through the bilayer.

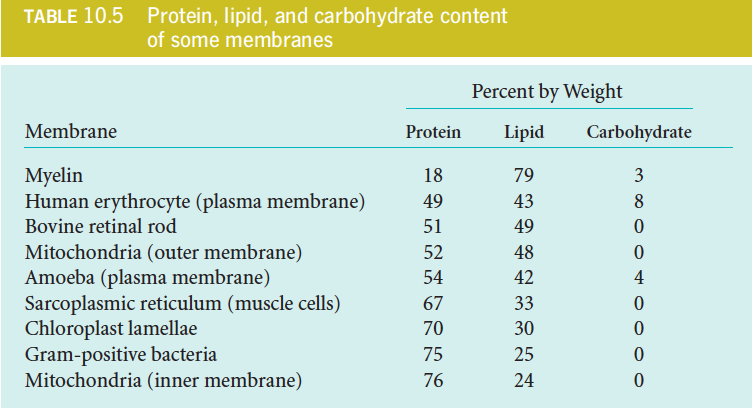

The protein content varies greatly among different kinds of membranes (see Table 10.5) and appears to be directly related to the functions a particular membrane must carry out.

Structure of a typical cell membrane

Proteins are embedded in and on the phospholipid bilayer;

Some of them are glycoproteins, carrying oligosaccharide chains.

The membrane is about 6 nm thick.

Most membranes are more densely packed with proteins than is shown here

Membrane Content

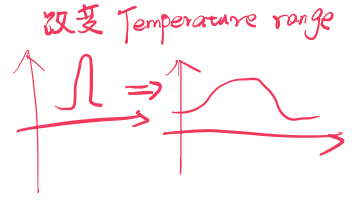

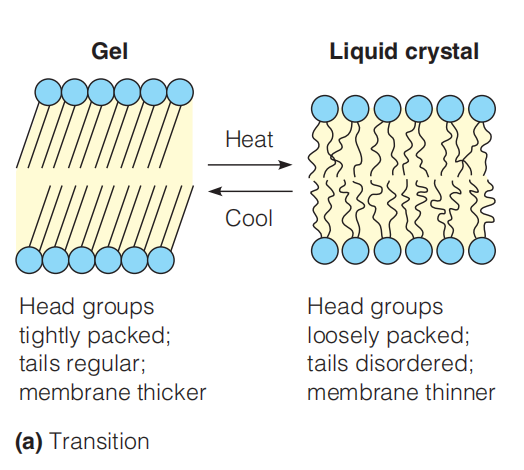

1. The gel–liquid crystalline phase transition in a synthetic lipid bilayer

The well-defined transition from gel to liquid is called melting of the membrane, which can be measured by calorimetry.

A schematic view of the change at the transition temperature. Below this temperature the hydrocarbon tails are packed together in a nearly crystalline gel state (left). Above this temperature the movement of the chains becomes more dynamic, and the interior of the membrane resembles a liquid hydrocarbon (right).

Detection of the transition by calorimetry. Measurement of the heat absorbed by a membrane as the temperature is raised each degree shows a sharp spike at the transition temperature (T*m) for a* pure dipalmitoylphosphatidyl choline bilayer. This well-defined transition from gel to liquid is called melting of the membrane. When 20 mol % cholesterol is mixed into the bilayer, the Tm is not changed, but the transition is broadened.

The transition temperature (T*m)* for a membrane depends on its lipid composition.

Lipids with longer, saturated tails tend to increase the Tm.

Those with more cis double bonds and/or shorter tails will reduce the Tm.

Under physiological conditions, biological membranes exist in a semi-fluid liquid crystalline state.

By mixing the cholesterol into the bilayer, the Tm is not changed, but the transition is broadened:

2. Motion in Biological Membranes

Biological membranes, which contain complex mixtures of lipid components plus protein, exhibit much broader and more complex phase transitions than those observed for synthetic bilayers of the kind described above.

The membrane composition is regulated so as to keep the transition temperature below the body temperature of the organism.

Membrane Composition Regulation Example In Bacteria

- alter the saturated/unsaturated fatty acid ratio in their membranes in response to a change in the temperature at which they are grown

Membrane Composition Regulation Example In Animal

A remarkable case in the animal kingdom is that of the rein-deer’s leg. Its cell membranes show an increase in relative amount of unsaturated fatty acids near the hoof, which is usually cooler than the rest of the body.

The Asymmetry of Membranes

In contrast to the ease of lateral movement, the “flip-flop” of lipid molecules across synthetic lipid bilayers (跨合成脂质双层的脂质分子的翻转)

The two leaflets of a membrane usually differ in lipid composition.

Because the two faces of a membrane must deal with different surroundings, the faces are usually quite different in composition and structure.

Lipid composition in the outer leaflet (green) and inner leaflet (gold) of the plasma membrane is graphed for three cell types.

- PC phosphatidylcholine

- PE phosphatidylethanolamine

- PS phosphatidylserine

- PI = phosphatidylinositol

- SP = sphingomyelin

Characteristics of Membrane Protein

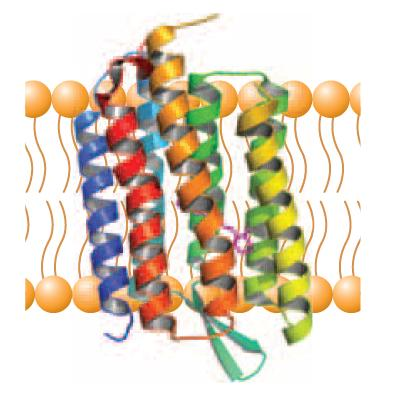

They often contain a high proportion of hydrophobic amino acids in the parts of the protein molecules that are embedded in the membrane (see Figure 10.15). The segments of proteins that span membranes are often α-helical, although β-barrels are also common membrane-spanning motifs.

Functions as a light-driven proton pump in certain bacteria.

Seven helices span the membrane and hold a molecule of the light-absorbing pigment retinal

Like many such proteins, it contains a bundle of seven -helical segments that pass back and forth through the membrane.

The presence of such transmembrane segments can sometimes be inferred from the kind of hydrophobicity plot shown in Figure 10.17.

It reveals maxima in regions of the sequence corresponding to the transmembrane helices. Transmembrane helices typically contain 20–25 residues, which are predominantly (主要) hydrophobic.

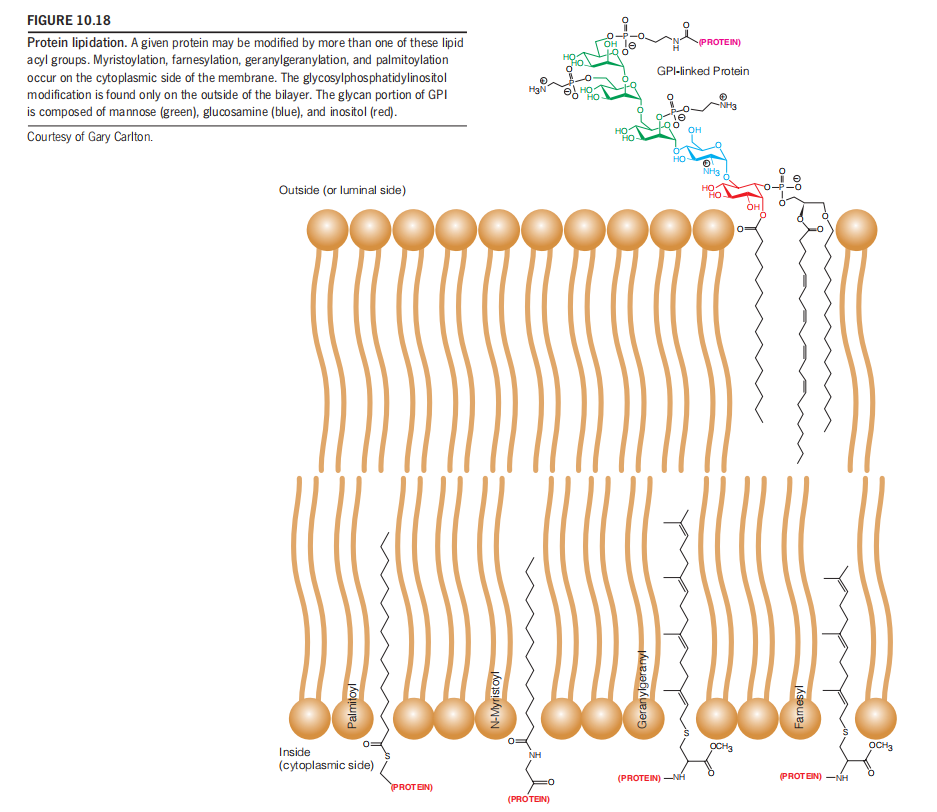

Another class of membrane-associated proteins is covalently modified with lipids as shown in Figure 10.18.

Insertion of Protein into Membranes

Signal Protein in the N-terminals to recognize the orientation

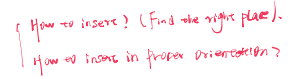

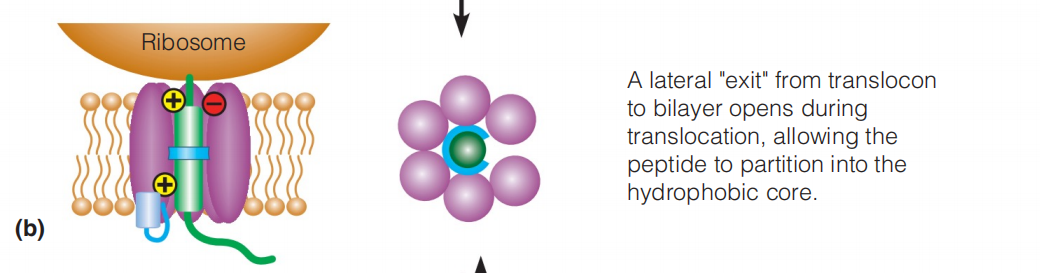

Co-translational insertion and folding of transmembrane helices in an integral membrane protein:

This process is facilitated by a protein-conducting channel called a translocon

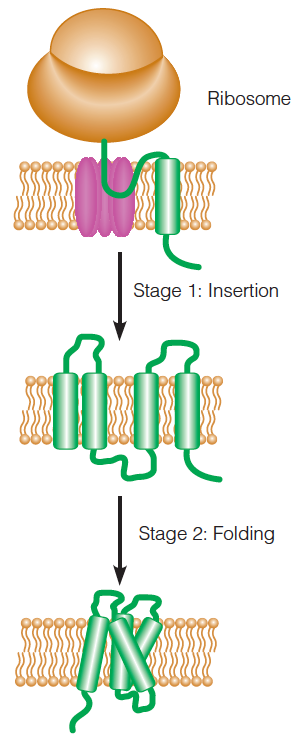

A protein channel called the “translocon (易位子)” facilitates the insertion of integral membrane proteins into the membrane bilayer.

The problems that the translocon may meet:

- First, it must allow the hydrophobic transmembrane sequences of the emerging, or “nascent,” protein to remain in the bilayer while conducting certain hydrophilic sequences across the membrane.

- Second, it must facilitate correct orientation, or “topology,” of the transmembrane sequences.

- The translocon must do all of this while preventing the nonspecific transport of other molecules or ions across the bilayer,

Some parts of the protein (in this case, the loops) are conducted across the bilayer through the translocon; transmembrane portions exit the translocon and remain embedded in the bilayer.

The mechanism of translocon:

One plausible explanation is that the channel opens along its length to allow the peptide to slide out laterally

The transmembrane helices fold after they are inserted.

(Helices because in hydrophobic environment, the H-bond is strong)

1. Model for translocon function

- The “resting” translocon.

- The “active” translocon.

- If a segment of the nascent (初期的;开始存在的,发生中的) peptide is sufficiently hydrophobic it will partition (分开, 分割) into the lipid bilayer.

Hydrophilic sequences (loops) partition to either side of the bilayer, depending on the orientation of the transmembrane segments.

2. The “inside positive” rule

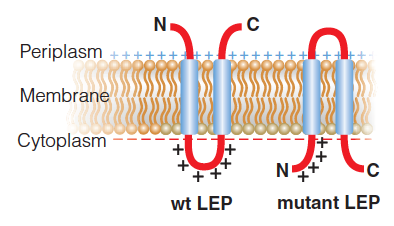

Work by Gunnar von Heijne and colleagues has supported an “inside positive” rule that explains the enrichment in Lys and Arg residues in the cytoplasmic portions of proteins with multiple membrane spanning regions.

Due to the electrical potential across the membrane, $\Delta \Psi$ ,the cytoplasmic side of the bilayer is more negatively charged compared to the outside; thus, a cluster of positively charged side chains would tend to migrate to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane.

This “inside positive” orientation of transmembrane proteins is also aided by the preponderance (占优势) of acidic (i.e., negatively charged) phospholipids on the inside of membranes. Finally, in some species, the translocon plays a role in directing the orientation of transmembrane peptides, via key charge–charge interactions.

Wild-type leader peptidase (Lep) from E. coli orients its two transmembrane helices with the termini in the periplasm and the loop between the helices in the cytoplasm.

Addition of four Lys to the N-terminus and removal of positive charge from the loop yield a mutant Lep that has the opposite membrane topology.

The membrane potential is indicated by greater negative charge on the cyotplasmic side compared to the periplasmic side

In the yeast translocon Sec61, basic residues on the periplasmic side and acidic residues on the cytoplasmic side of the channel (see Figure 10.24b)

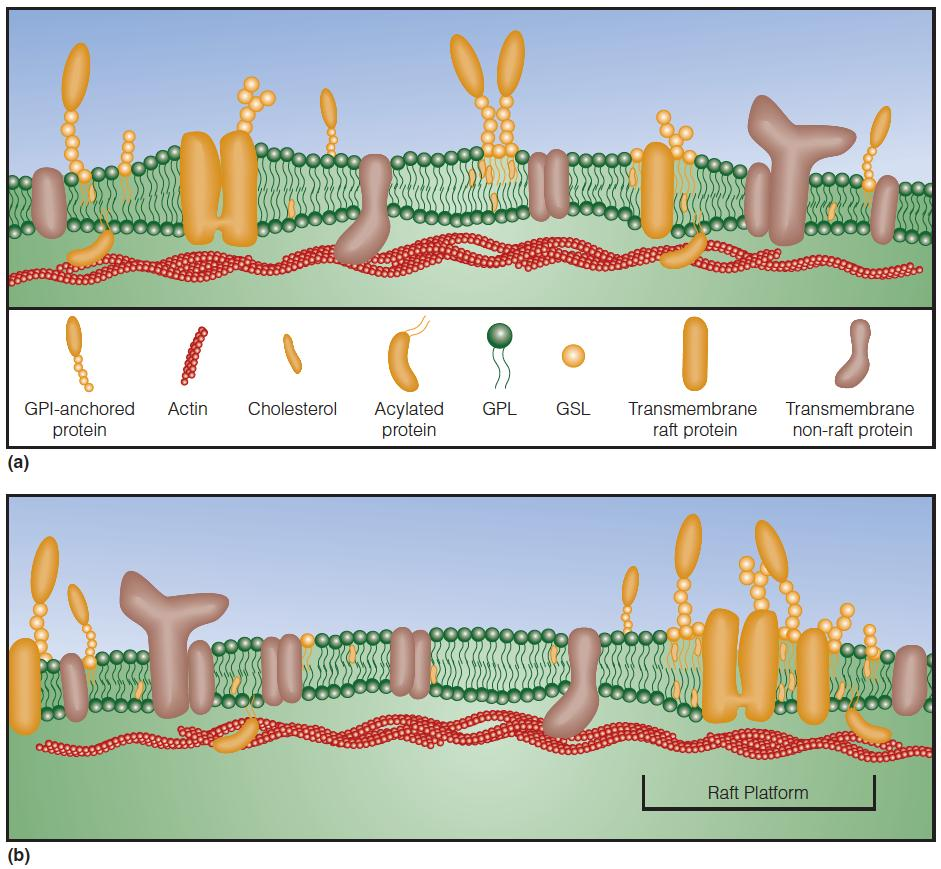

3. Evolution of the Fluid Mosaic Model of Membrane Structure

Specifically, most membranes appear to be very crowded with proteins and show significant variation in both thickness of the bilayer and distribution of proteins and lipids within a leaflet.

Membrane rafts are rich in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and GPI-linked proteins.

These membrane rafts are small short-lived dynamic structures that, in response to certain stimuli, can transiently associate with each other to form larger “raft platforms”

These raft platforms are thought to play significant roles in cell signaling and the sorting of proteins into specific organelles within a cell.

Membrane thickness is also influenced by the proteins in the bilayer

The bilayer is thicker in rafts than in the surrounding membrane.

The proteins coalesce and form nanometer-sized dynamic raft domains, which may be stabilized by interactions with actin fibers.

Rafts can associate to form larger structures (“platforms”).

Certain proteins interact preferentially with rafts (orange shading), while others do not (brown shading) or are excluded.

Lipid Curvature and Protein Function

protein composition, rather than lipid composition, is the major determinant of membrane thickness.

The lipid bilayer exerts significant lateral pressure on embedded proteins. This pressure can be up to 400 atm, and it arises due to the balancing of attractive and repulsive forces in the plane of the bilayer.

If the membrane surrounding a cell or organelle expands or contracts, the resulting change in bilayer curvature will alter the magnitude and position of the forces acting on imbedded proteins.

Thus, a mechanical stress on the bilayer is translated to these proteins. Such stress can alter protein conformation