L8 Emotion

Emotion enriches our lives with its “buzzing, humming, soaring, and roaring.”

It also motivates our behavior: Anger intensifies our defensive behavior, fear accelerates flight, and happiness encourages the behaviors that produce it.

Emotion adds emphasis to experiences as they are processed in the brain, making them more memorable (A. K. Anderson & Phelps, 2001); as a result, we are likely to repeat the behaviors that bring joy and avoid the ones that produce danger or pain.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal components of an emotional response and the role of the amygdala in controlling them.

- Discuss the nature, functions, and neural control of aggressive behavior.

- Discuss the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in anger, aggression, and impulse control.

- Discuss cross-cultural studies on the expression and comprehension of emotions.

- Discuss the neural control of the recognition of emotional expression.

- Discuss the neural control of emotional expression.

- Discuss the James-Lange theory of feelings of emotion and evaluate relevant research.

一、Emotions as Response Patterns

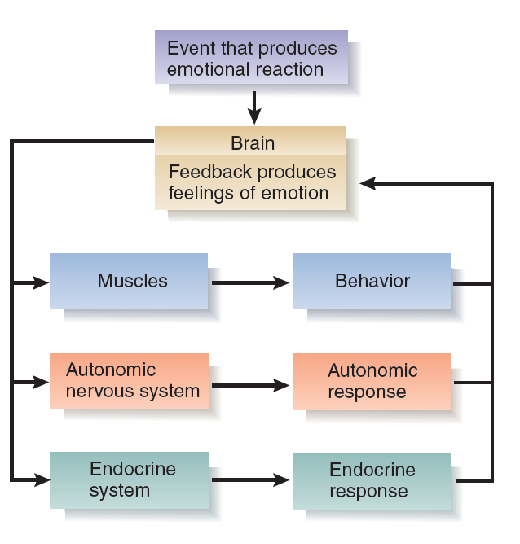

An emotional response consists of three types of components:

Behavioral component(行为成分) consists of muscular movements that are appropriate to the situation that elicits them.

For example, a dog defending its territory against an intruder first threatens the intruder by adopting an aggressive posture, growling, and showing its teeth. If the intruder does not leave, the defender runs toward the intruder and attacks.

Autonomic responses(自主反应) facilitate the behaviors and provide quick mobilization of energy for vigorous movement.

In this example the activity of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system increases while that of the parasympathetic branch decreases. As a consequence the dog’s heart rate increases, and changes in the size of blood vessels shunt the circulation of blood away from the digestive organs toward the muscles.

- Hormonal responses(激素反应) reinforce the autonomic responses.

- The hormones secreted by the adrenal medulla—epinephrine and norepinephrine—further increase blood flow to the muscles and cause nutrients stored in the muscles to be converted into glucose. In addition, the adrenal cortex secretes steroid hormones, which also help to make glucose available to the muscles.

As you will see, negative emotions receive much more attention than positive ones.

Most of the research on the physiology of emotions has been confined to fear and anger—emotions associated with situations in which we must defend ourselves or our loved ones.

The physiology of behaviors associated with positive emotions—such as those associated with lovemaking, caring for one’s offspring, or enjoying a good meal or a cool drink of water (or some other beverage)—is described in other chapters.

The consequence of situations that evoke negative emotions, stress, will be discussed in Chapter 12.

Fear

Fear

- Emotional responses involve behavioral, autonomic and hormonal components.

- These components are controlled by separate neural systems.

- Integration of components of fear appears to be controlled by the amygdala.

Single neurons in various nuclei of the amygdala become active when emotionally relevant stimuli are presented.

For example, these neurons are excited by such stimuli as the sight of a device that has been used to squirt either a bad-tasting solution or a sweet solution into the animal’s mouth, the sound of another animal’s vocalization, the sound of the opening of the laboratory door, the smell of smoke, or the sight of another animal’s face.

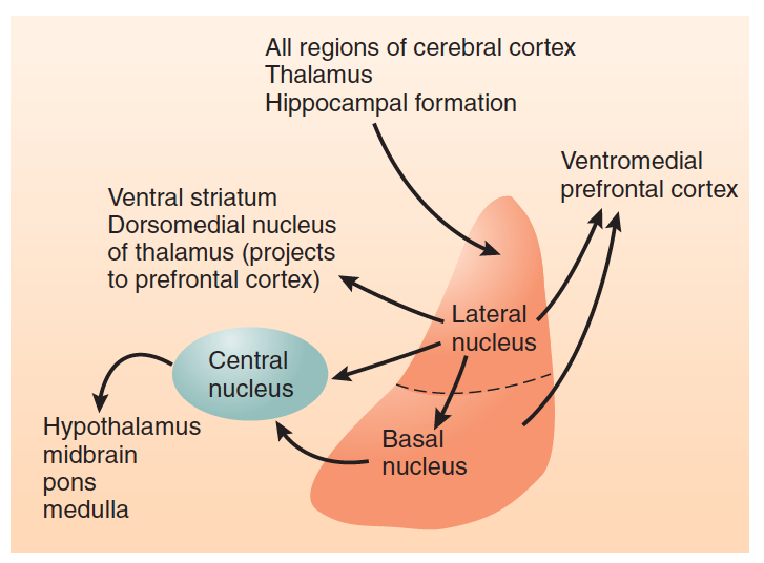

- This much-simplified diagram shows the major divisions and connections of the amygdala that play a role in emotions.

The amygdala (or more precisely, the amygdaloid complex) is located within the temporal lobes.

The amygdala has been subdivided into approximately twelve regions, each containing several subregions. However, we only need to concern ourselves with three major regions: the lateral nucleus(外侧核), the basal nucleus(基底核), and the central nucleus(中央核).

Activation of the central nucleus elicits a variety of emotional responses: behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal.

The central nucleus of the amygdala is the single most important part of the brain for the expression of emotional responses provoked by aversive stimuli(厌恶刺激). When threatening stimuli are perceived, neurons in the central nucleus become activated. 、

Damage to the central nucleus reduces or abolishes a wide range of emotional behaviors and physiological responses.

After the central nucleus has been destroyed, animals no longer show signs of fear when confronted with stimuli that have been paired with aversive events.

They also act more tamely when handled by humans, their blood levels of stress hormones are lower, and they are less likely to develop ulcers or other forms of stress-induced illnesses.

Normal monkeys show signs of fear when they see a snake, but those with amygdala lesions do not.

In contrast, when the central amygdala is stimulated by means of electricity or by an injection of an excitatory amino acid, the animal shows physiological and behavioral signs of fear and agitation, and long-term stimulation of the central nucleus produces stress-induced illnesses such as gastric ulcers.

These observations suggest that the autonomic and endocrine responses controlled by the central nucleus are among those responsible for the harmful effects of long-term stress.

A few stimuli automatically activate the central nucleus of the amygdala and produce fear reactions—for example, loud unexpected noises, the approach of large animals, heights, or (for some species) specific sounds or odors.

Even more important, however, is the ability to learn that a particular stimulus or situation is dangerous or threatening. Once the learning has taken place, that stimulus or situation will evoke fear; heart rate and blood pressure will increase, the muscles will become more tense, the adrenal glands will secrete epinephrine, and the animal will proceed cautiously, alert and ready to respond.

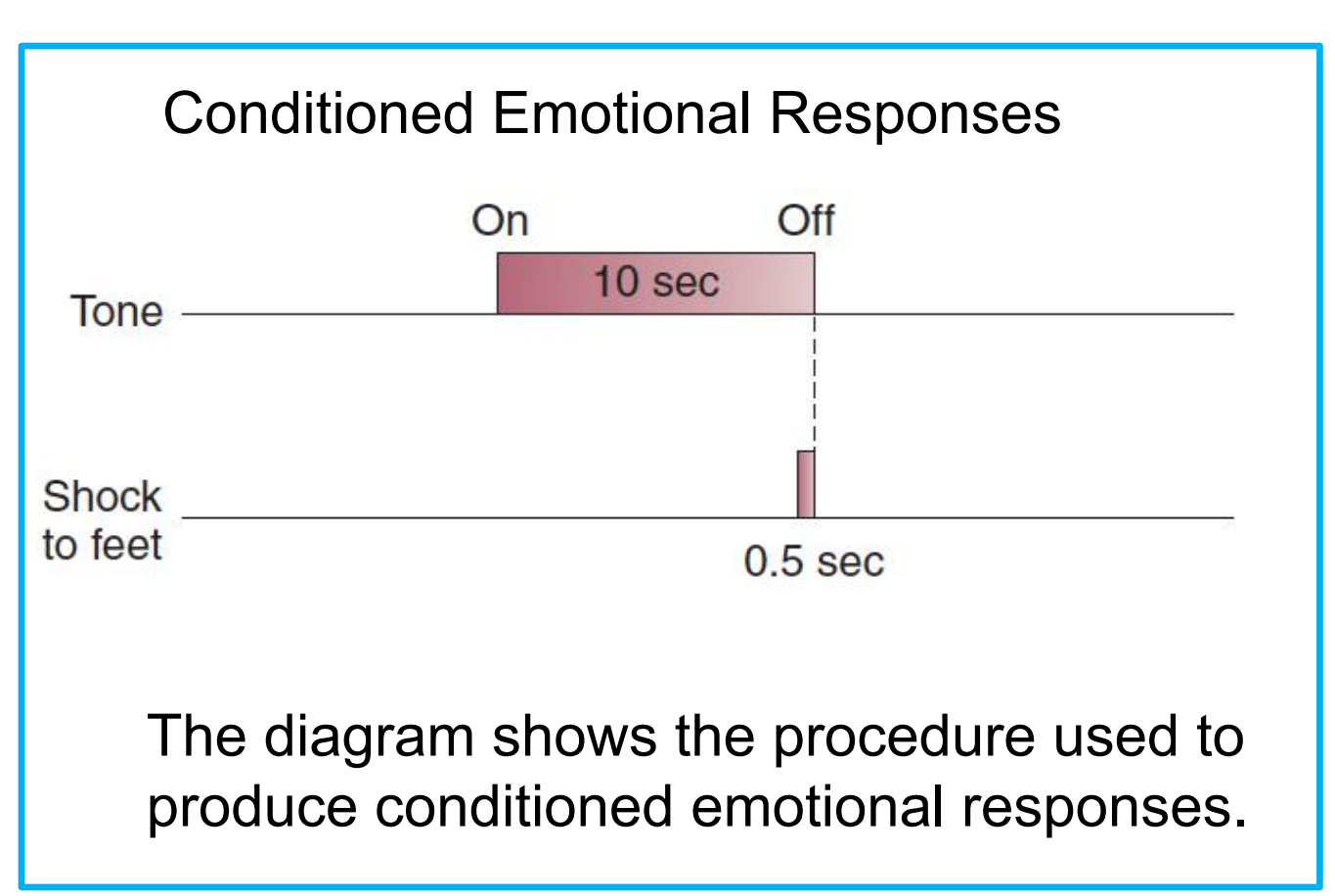

1. Conditioned Emotional Response

Classically conditioned response that occurs when neutral stimulus is followed by an aversive stimulus.

Usually includes autonomic, behavioral, and endocrine components such as changes in heart rate, freezing, and secretion of stress-related hormones.

The role of the amygdala in the development of classically conditioned emotional responses.

These conditioned emotional responses can be produced in rats by presenting an auditory stimulus such as a tone, followed by a brief electrical shock delivered to the feet through the floor on which the animals are standing.

By itself the shock produces an unconditional emotional response: The animal jumps into the air, its heart rate and blood pressure increase, its breathing becomes more rapid, and its adrenal glands secrete catecholamines and steroid stress hormones. After several pairings of the tone and the shock, classical conditioning is normally established.

The tone becomes a conditional stimulus (CS) that elicits freezing: a conditional response (CR).

2. Brain area responsible for conditioned emotional response

Research indicates that the physical changes responsible for the establishment of a conditioned emotional response take place in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala (Paré, Quirk, and LeDoux, 2004).

Extinguish of conditioned emotional response

The neural mechanisms responsible for classically conditioned emotional responses evolved because they play a role in an animal’s survival by increasing the likelihood that they can avoid dangerous situations, such as places where they encountered aversive events.

If the conditional stimulus (CS: tone) is presented repeatedly by itself, the previously established conditional response (CR: emotional response) eventually disappears—it becomes extinguished.

After all, the value of a conditioned emotional response is that it prepares an animal to confront (or better yet, avoid) an aversive stimulus. If the CS occurs repeatedly but the aversive stimulus does not follow, then it is better for the emotional response—which itself is disruptive and unpleasant—to disappear. And that is exactly what happens.

Brain area responsible for extinction of conditioned emotional response

Behavioral studies have shown that extinction is not the same as forgetting. Instead, the animal learns that the CS is no longer followed by an aversive stimulus, and as a result of this learning, the expression of the CR is inhibited; the memory for the association between the CS and the aversive stimulus is not erased. This inhibition is supplied by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) .

- Lesions of the vmPFC impair extinction

- Stimulation of this region inhibits conditioned emotional responses

- Extinction training activates neurons there.

3. Research with Humans

Evidence indicates that the amygdala is involved in emotional responses in humans.

One of the earliest studies observed the reactions of people who were being evaluated for surgical removal of parts of the brain to treat severe seizure disorders. These studies found that stimulation of parts of the brain (for example, the hypothalamus) produced autonomic responses that are often associated with fear and anxiety but that only when the amygdala was stimulated did people also report that they actually felt afraid (White, 1940; Halgren et al., 1978; Gloor et al., 1982).

- Many studies have shown that lesions of the amygdala decrease people’s emotional responses. For example, Bechara et al. (1995) and LaBar et al. (1995) found that people with lesions of the amygdala showed impaired acquisition of a conditioned emotional response, just as rats do.

Most human fears are probably acquired socially, not through firsthand experience with painful stimuli (Olsson, Nearing, and Phelps, 2007).

For example, a child does not have to be attacked by a dog to develop a fear of dogs: He or she can develop this fear by watching another person being attacked or (more often) by seeing another person display signs of fear when encountering a dog.

People can also acquire a conditioned fear response through instruction.

For example, suppose that someone is told (and believes) that if a warning light in a control panel goes on, he or she should leave the room immediately, because the light is connected to a sensor that detects toxic fumes. If the light does go on, the person will leave the room, and is also likely to experience a fear response while doing so.

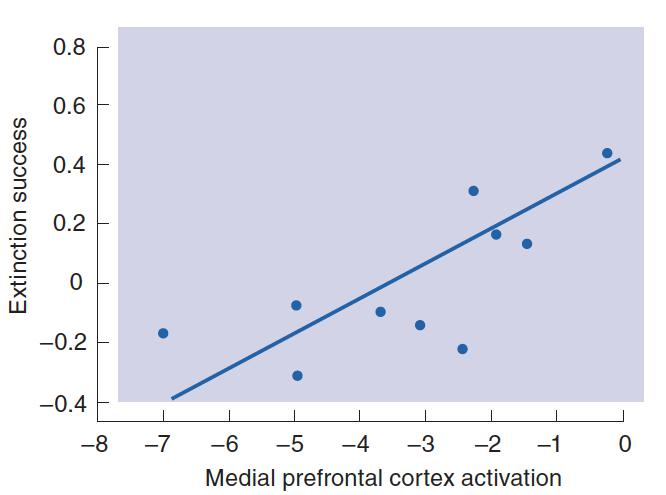

We saw that studies with laboratory animals indicate that the vmPFC plays a critical role in extinction of a conditioned emotional response. The same is true for humans.

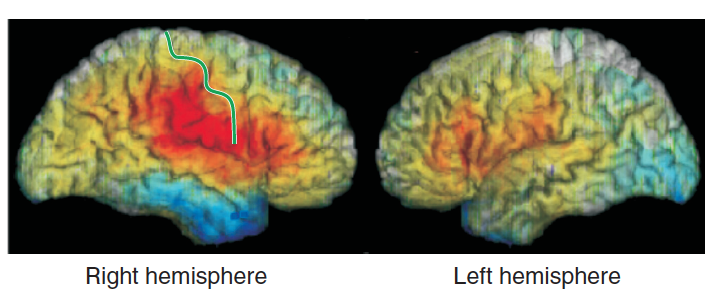

Phelps et al. (2004) directly established a conditioned emotional response in human subjects by pairing the appearance of a visual stimulus with electric shocks to the wrist and then extinguished the response by presenting the squares alone, without any shocks. As the following figure showed, increased activity of the medial prefrontal cortex correlated with extinction of the conditioned response.

- This graph shows that activation of the medial prefrontal cortex is related to the extinction of a conditioned emotional response.

As we saw earlier, Patient I. R., a woman who had sustained damage to the auditory association cortex, was unable to perceive or produce melodic or rhythmic aspects of music (Peretz et al., 2001). She could not even tell the difference between consonant (pleasant) and dissonant (unpleasant) music. However, she was still able to recognize the mood conveyed by music.

Gosselin et al. (2005) found that patients with damage to the amygdala showed the opposite symptoms: They had no trouble with musical perception but were unable to recognize scary music. They could still recognize happy and sad music. Thus, amygdala lesions impair recognition of a musical style that is normally associated with fear.

Anger, Aggression, and Impulse Control

Almost all species of animals engage in aggressive behaviors, which involve threatening gestures or actual attack directed toward another animal.

Aggressive behaviors are species-typical; that is, the patterns of movements (for example, posturing, biting, striking, and hissing) are organized by neural circuits whose development is largely programmed by an animal’s genes.

Many aggressive behaviors are related to reproduction. For example, aggressive behaviors that gain access to mates, defend territory needed to attract mates or to provide a site for building a nest, or defend offspring against intruders can all be regarded as reproductive behaviors.

Other aggressive behaviors are related to self-defense, such as that of an animal threatened by a predator or an intruder of the same species.

1. Neural Control of Aggressive Behavior

The neural control of aggressive behavior is hierarchical(分层的).

The particular muscular movements an animal makes in attacking or defending itself are programmed by neural circuits in the brain stem.

Whether an animal attacks depends on many factors, including the nature of the eliciting stimuli in the environment and the animal’s previous experience. The activity of the brain stem circuits appears to be controlled by the hypothalamus and the amygdala, which also influence many other species-typical behaviors.

Role of Serotonin

An overwhelming amount of evidence suggests that the activity of serotonergic synapses inhibits aggression.

In contrast, destruction of serotonergic axons in the forebrain facilitates aggressive attack, presumably by removing an inhibitory effect (Vergnes et al., 1988).

- Study of free-ranging colonies of rhesus monkeys has provided important information about the role of serotonin in risk-taking behavior and aggression.

A group of researchers has studied the relationship between serotonergic activity and aggressiveness in a free-ranging colony of rhesus monkeys (reviewed by Howell et al., 2007).

The researchers assessed serotonergic activity by capturing the monkeys, removing a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, and analyzing it for 5-HIAA, a metabolite of serotonin (5-HT). When 5-HT is released, most of the neurotransmitter is taken back into the terminal buttons by means of reuptake, but some escapes and is broken down to 5-HIAA, which finds its way into the cerebrospinal fluid. Thus, high levels of 5-HIAA in the CSF indicate an elevated level of serotonergic activity. 0

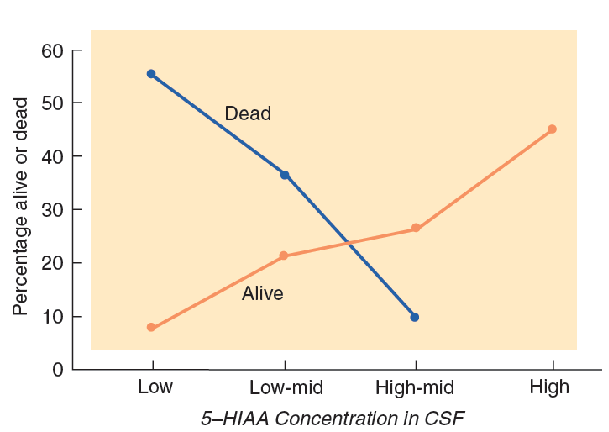

- The graph shows the percentage of young male monkeys alive or dead as a function of 5-HIAA level in the CSF, measured four years previously.

The investigators found that young male monkeys with the lowest levels of 5-HIAA showed a pattern of risk-taking behavior, including high levels of aggression directed toward animals that were older and much larger than themselves. They were much more likely to take dangerous unprovoked long leaps from tree to tree at a height of more than 7 meters. They were also more likely to pick fights that they could not possibly win. Of the preadolescent male monkeys that the investigators followed for four years, a large percentage of those with the lowest 5-HIAA levels died, while all of the monkeys with the highest levels survived. Most of the monkeys that died were killed by other monkeys. In fact, the first monkey to be killed had the lowest level of 5-HIAA and was seen attacking two mature males the night before his death.

- Clearly, serotonin does not simply inhibit aggression; rather, it exerts a controlling influence on risky behavior, which includes aggression.

Human violence and aggression are serious social problems.

- Early experiences can certainly foster development of aggressive behavior, but studies demonstrate that heredity plays a significant role.

- Several studies found that serotonergic neurons play an inhibitory role in human aggression.

For example, a depressed rate of serotonin release (indicated by low levels of 5-HIAA in the CSF) is associated with aggression and other forms of antisocial behavior, including assault, arson, murder, and child beating.

If low levels of serotonin release contribute to aggression, perhaps drugs that act as serotonin agonists might help to reduce antisocial behavior. In fact, a study by Coccaro and Kavoussi (1997) found that fluoxetine (Prozac), a serotonin agonist, decreased irritability and aggressiveness, as measured by a psychological test.

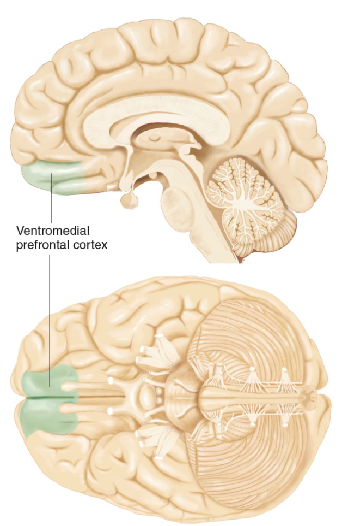

Role of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex

Many investigators believe that impulsive violence is a consequence of faulty emotional regulation.

For most of us, frustrations may elicit an urge to respond emotionally, but we usually manage to calm ourselves and suppress these urges. As we shall see, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex plays an important role in regulating our responses to such situations.

The analysis of social situations involves much more than sensory analysis; it involves experiences and memories, inferences and judgments. In fact, the skills involved include some of the most complex ones we possess. These skills are not localized in any one part of the cerebral cortex, although research does suggest that the right hemisphere is more important than the left. Nonetheless, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex—which includes the medial orbitofrontal cortex and the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex—plays a special role.

The Location of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex

As we saw earlier in the discussion of the process of extinction, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) plays a role in inhibiting emotional responses. The vmPFC is located just where its name suggests, at the bottom front of the cerebral hemispheres.

- The vmPFC receives direct inputs from the dorsomedial thalamus, temporal cortex, ventral tegmental area, olfactory system, and amygdala.

- Its outputs go to several brain regions, including the cingulate cortex, hippocampal formation, temporal cortex, lateral hypothalamus, and amygdala.

Finally, it communicates with other regions of the prefrontal cortex. Thus, its inputs provide it with information about what is happening in the environment and what plans are being made by the rest of the frontal lobes, and its outputs permit it to affect a variety of behaviors and physiological responses, including emotional responses organized by the amygdala.

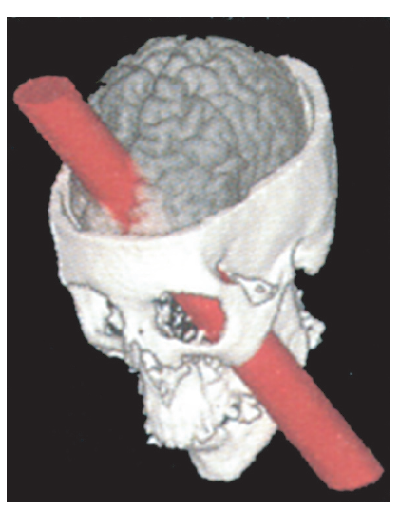

The first—and most famous—case comes from the mid-1800s. Phineas Gage, the foreman of a railway construction crew, was using a steel rod to ram a charge of blasting powder into a hole drilled in solid rock. Suddenly, the charge exploded and sent the rod into his cheek, through his brain, and out the top of his head. He survived, but he was a different man. Before his injury he was serious, industrious, and energetic. Afterward, he became childish, irresponsible, and thoughtless of others. He was unable to make or carry out plans, and his actions appeared to be capricious and whimsical. His accident had largely destroyed the orbitofrontal cortex (Damasio et al., 1994).

- In the accident the steel rod entered his left cheek and exited through the top of his head

Damage to the vmPFC causes serious and often debilitating impairments of behavioral control and decision-making. These impairments appear to be a consequence of emotional dysregulation.

Anderson et al. (2006) obtained ratings of emotional behaviors of patients with damage to the vmPFC—such as frustration tolerance, emotional instability, anxiety, and irritability—from the patients’ relatives.

They also obtained ratings of the patients’ real-world competencies, such as judgment, planning, social inappropriateness, and financial and occupational status, from both relatives and clinicians. They found a significant correlation between emotional dysfunction and impairments in real-world competencies. There was no relation between these impairments and the patients’ cognitive abilities, which strongly suggests that emotional problems, and not problems in cognition, lie at the base of the real-world difficulties exhibited by people with vmPFC damage.

Evidence suggests that emotional reactions guide moral judgments as well as decisions involving personal risks and rewards and that the prefrontal cortex plays a role in these judgments as well.

Consider the following moral dilemma (Thomson, 1986): You see a runaway trolley with five people aboard hurtling down a track leading to a cliff. Without your intervention these people will soon die. However, you are standing near a switch that will shunt the trolley off to another track, where the vehicle will stop safely. But a worker is standing on that track, and he will be killed if you throw the switch to save the five helpless passengers. Should you stand by and watch the trolley go off the cliff, or should you save them—and kill the man on the track?

Whether we kill someone by sending a trolley his way or by pushing him off a bridge into the path of an oncoming trolley, he dies when the trolley strikes him. But somehow, imagining yourself pushing a person’s body and causing his death seems more emotionally wrenching than throwing a switch that changes the course of a runaway trolley.

Thus, moral judgments appear to be guided by emotional reactions and are not simply the products of rational, logical decision-making processes.

Considering whether to throw a switch to cause one death but save five other lives evokes a much smaller emotional reaction than considering whether to shove someone on the tracks to accomplish the same goal. Indeed, considering the second dilemma, and not the first, strongly activates the vmPFC.

Therefore, we might expect people with vmPFC damage to be more willing to push the man onto the track in the second dilemma.

In fact, that is exactly what they do: They demonstrate utilitarian moral judgment: Killing one person is better than letting five people get killed.

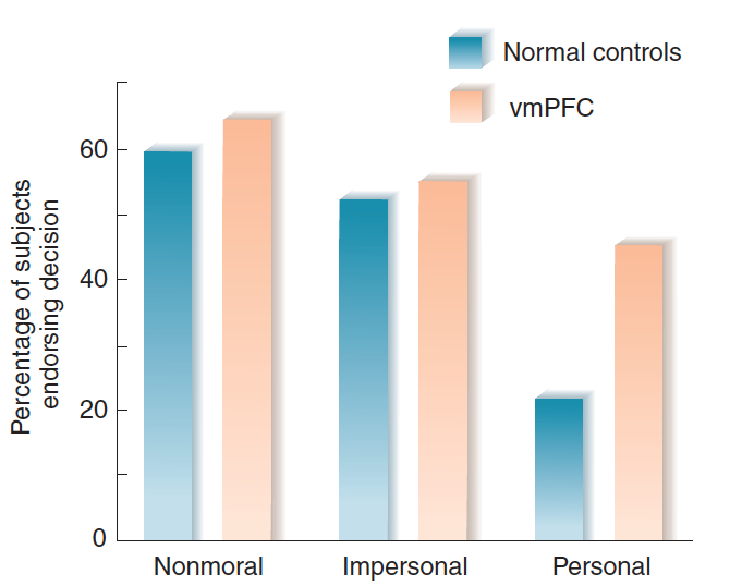

Koenigs et al. (2007) presented nonmoral, impersonal moral, and personal moral scenarios to patients with vmPFC lesions, patients with brain damage not including this region, and normal controls. For example, the switch-throwing scenario we just considered is an impersonal moral dilemma, and the person-pushing dilemma is a personal moral dilemma.

Moral Decisions and the vmPFC

The graph shows the percentage of people with lesions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and normal controls who endorse decisions of nonmoral, impersonal moral, and personal moral scenarios like the ones listed in last table

2. Research with Humans

Many investigators believe that impulsive violence is a consequence of faulty emotional regulation.

The amygdala plays an important role in provoking anger and violent emotional reactions, and the prefrontal cortex plays an important role in suppressing such behavior by making us see its negative consequences.

As we saw earlier, antisocial behavior may be associated with decreased volume of the prefrontal cortex; thus, activation of the prefrontal cortex may reflect its role in inhibiting aggressive behavior.

Raine et al. (1998) found evidence of decreased prefrontal activity and increased subcortical activity (including the amygdala) in the brains of convicted murderers. These changes were primarily seen in impulsive, emotional murderers.

The prefrontal activity of cold-blooded, calculating, predatory murderers—whose crimes were not accompanied by anger and rage—was closer to normal.

Presumably, increased activation of the amygdala reflected an increased tendency for display of negative emotions, and the decreased activation of the prefrontal cortex reflected a decreased ability to inhibit the activity of the amygdala and thus control the people’s emotions. Raine et al. (2002) found that people with antisocial personality disorder showed an 11 percent reduction in volume of the gray matter of the prefrontal cortex.

Earlier in this chapter we saw that decreased activity of serotonergic neurons is associated with aggression, violence, and risk taking.

As we saw in this subsection, decreased activity of the prefrontal cortex is also associated with antisocial behavior.

These two facts appear to be linked. The prefrontal cortex receives a major projection of serotonergic axons.

- Research indicates that serotonergic input to the prefrontal cortex activates this region.

A functional imaging study by New et al. (2004) measured regional brain activity of people with histories of impulsive aggression before and after twelve weeks of treatment with a specific serotonin reuptake inhibitor. They found that the drug increased the activity of the prefrontal cortex and reduced aggressiveness.

Crockett et al. (2010) found that a single high dose of a 5-HT agonist decreased the likelihood of subjects making a decision to cause harm in scenarios that presented moral dilemmas. In other words, the increased serotonergic activity made them less likely to make utilitarian decisions. It seems likely, therefore, that an abnormally low level of serotonin release can result in decreased activity of the prefrontal cortex and increased likelihood of utilitarian judgments or, in the extreme, antisocial behavior.

二、Communication of Emotions

The previous section described emotions as organized responses (behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal) that prepare an animal to deal with existing situations in the environment, such as events that pose a threat to the organism. For our earliest premammalian ancestors, that is undoubtedly all there was to emotions.

But over time other responses, with new functions, evolved.

Many species of animals (including our own) communicate their emotions to others by means of postural changes, facial expressions, and nonverbal sounds (such as sighs, moans, and growls).

These expressions serve useful social functions; they tell other individuals how we feel and—more to the point—what we are likely to do.

- For example, they warn a rival that we are angry or tell friends that we are sad and would like some comfort and reassurance. They can also indicate that a danger might be present or that something interesting seems to be happening.

This section examines such expression and communication of emotions.

Facial Expression of Emotions: Innate Responses

Research by Ekman and his colleagues (Ekman and Friesen, 1971; Ekman, 1980) tends to confirm Darwin’s hypothesis that facial expression of emotion uses an innate, species-typical repertoire of movements of facial muscles (Darwin, 1872/1965).

For example, Ekman and Friesen (1971) studied the ability of members of an isolated tribe in New Guinea to recognize facial expressions of emotion produced by Westerners. They had no trouble doing so and themselves produced facial expressions that Westerners readily recognized.

- The tribesman made faces when told stories: (a) “Your friend has come and you are happy.” (b) “Your child had died.” (c) “You are angry and about to fight.” (d) “You see a dead pig that has been lying there a long time.”

Other researchers have compared the facial expressions of blind and normally sighted people. They reasoned that if the facial expressions of the two groups are similar, then the expressions are natural for our species and do not require learning by imitation.

In fact, the facial expressions of young blind and sighted children are very similar (Woodworth and Schlosberg, 1954; Izard, 1971).

In addition, a study of the emotional expressions of people competing in (and winning or losing) athletic events in the 2004 Paralympic Games found no differences between the expressions of congenitally blind, noncongenitally blind, and sighted athletes (Matsumoto and Willingham, 2009).

Thus, both the cross-cultural studies and the investigations of blind people confirm the naturalness of these facial expressions of emotion.

Neural Basis of the Communication of Emotions: Recognition

Effective communication is a two-way process. That is, the ability to display one’s emotional state by changes in expression is useful only if other people are able to recognize them.

In fact, Kraut and Johnston (1979) unobtrusively observed people in circumstances that would be likely to make them happy. They found that happy situations (such as making a strike while bowling, seeing the home team score, or experiencing a beautiful day) produced only small signs of happiness when the people were alone. However, when the people were interacting socially with other people, they were much more likely to smile. For example, bowlers who made a strike usually did not smile when the ball hit the pins, but when they turned around to face their companions, they often smiled. Jones et al. (1991) found that even 10-month-old children showed this tendency.

1. Laterality of Emotional Recognition

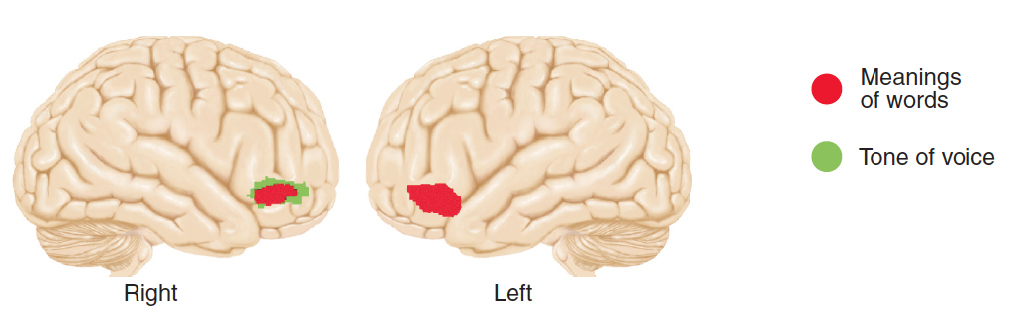

We recognize other people’s feelings by means of vision and audition—seeing their facial expressions and hearing their tone of voice and choice of words.

Many studies have found that the right hemisphere plays a more important role than the left hemisphere in comprehension of emotion.

For example, George et al. (1996) measured subjects’ regional cerebral blood flow while the subjects listened to some sentences and identified their emotional content. In one condition the subjects listened to the meaning of the words and said whether they described a situation in which someone would be happy, sad, angry, or neutral. In another condition they judged the emotional state from the tone of the voice. The intvestigators found that comprehension of emotion from word meaning increased the activity of the prefrontal cortex bilaterally, the left more than the right. Comprehension of emotion from tone of voice increased the activity of only the right prefrontal cortex.

Perception of emotions:

- The PET scans indicate brain regions activated by listening to emotions expressed by tone of voice (green) or by meanings of words (red).

Heilman, Watson, and Bowers (1983) recorded a particularly interesting case of a man with a disorder called pure word deafness, caused by damage to the left temporal cortex. The man could not comprehend the meaning of speech but had no difficulty identifying the emotion being expressed by its intonation. This case, like the functional imaging study by George et al. (1996), indicates that comprehension of words and recognition of tone of voice are independent functions

2. Role of the Amygdala

As we saw in the previous section, the amygdala plays a special role in emotional responses. It plays a role in emotional recognition as well.

For example, several studies have found that lesions of the amygdala (the result of degenerative diseases or surgery for severe seizure disorders) impair people’s ability to recognize facial expressions of emotion, especially expressions of fear.

In addition, functional imaging studies have found large increases in the activity of the amygdala when people view photographs of faces expressing fear but only small increases (or even decreases) when they look at photographs of happy faces. However, amygdala lesions do not appear to affect people’s ability to recognize emotions in tone of voice.

Krolak-Salmon et al. (2004) recorded electrical potentials from the amygdala and visual association cortex through electrodes that had been implanted in people who were being evaluated for neurosurgery to alleviate a seizure disorder. They presented the people with photographs of faces showing neutral expressions or expressions of fear, happiness, or disgust.

The found that fearful faces produced the largest response and that the amygdala showed activity before the visual cortex did. The rapid response suggests that visual information that the amygdala receives directly from the subcortical visual system (which conducts information very rapidly) permits it to recognize facial expressions of fear.

Neural Basis of the Communication of Emotions: Expression

1. The Mirror Neuron System

Adolphs et al. (2000) discovered a possible link between somatosensation and emotional recognition. They found that the most severe damage to this ability was caused by damage to the somatosensory cortex of the right hemisphere.

Brain Damage and Recognition of Facial Expressions of Emotion:

This computer-generated image shows performance of subjects with localized brain damage on recognition of facial expressions of emotion. The colored areas outline the site of the lesions. Lesions that resulted in good performance are shown in shades of blue; those that resulted in poor performance are shown in red and yellow

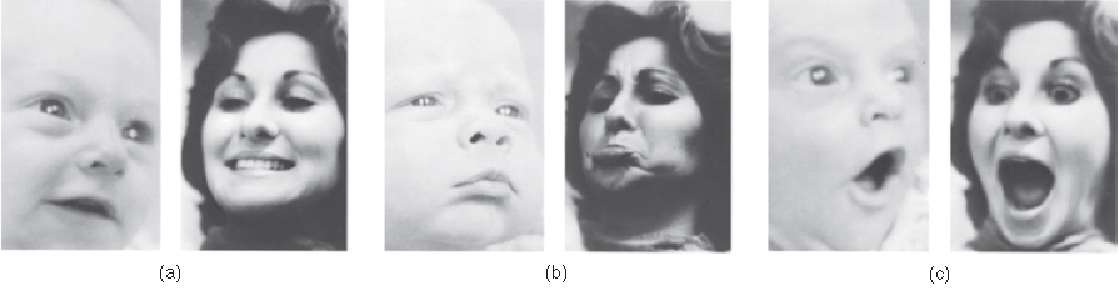

When we see a facial expression of an emotion, we unconsciously imagine ourselves making that expression. Often, we do more than imagine making the expressions—we actually imitate what we see.

Imitation in an Infant:

- The photographs show happy, sad, and surprised faces posed by an adult and the responses made by the infant.

Adolphs et al. suggest that the somatosensory representation of what it feels like to make the perceived expression provides cues we use to recognize the emotion being expressed in the face we are viewing.

In support of this hypothesis, Adolphs and his colleagues report that the ability of patients with right hemisphere lesions to recognize facial expressions of emotions is correlated with their ability to perceive somatosensory stimuli. That is, patients with somatosensory impairments (caused by right-hemisphere lesions) also had impairments in recognition of emotions.

Hussey and Safford (2009) supports this hypothesis (the so-called simulationist hypothesis). For example, neuroimaging studies have shown that brain regions that are activated when particular emotional expressions are observed are also activated when these expressions are imitated.

In addition, a study by Pitcher et al. (2008) used transcranial magnetic stimulation to disrupt the normal activity of brain regions involved in visual perception of faces or perception of somatosensory feedback from one’s own face. They found that disruption of either region impaired people’s ability to recognize facial expressions of emotion.

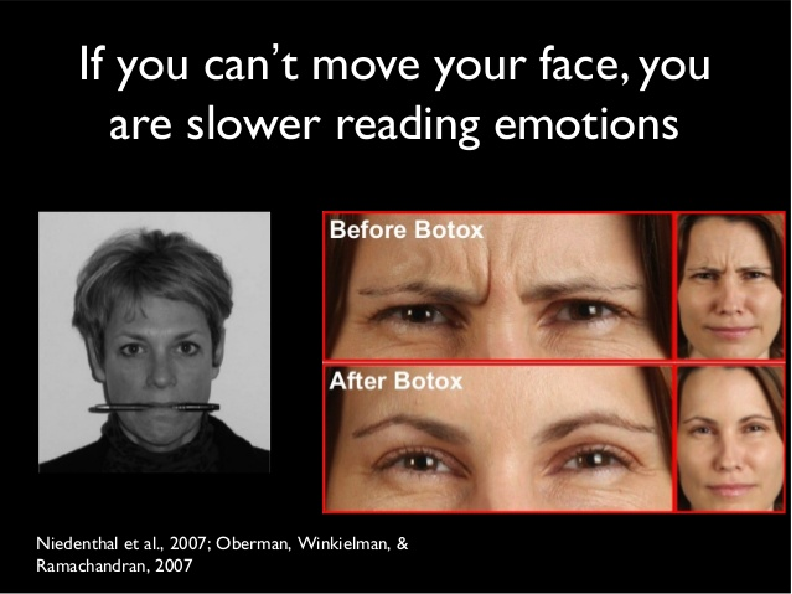

Finally, a study by Oberman et al. (2007) had people hold a pen between their teeth, which interfered with smiling. When they did so, they had difficulty recognizing facial expressions of happiness, but not expressions of disgust, fear, and sadness, which involve the upper part of the face more than smiling does.

A neurological disorder known as Moebius syndrome provides further support for this hypothesis. Moebius syndrome is caused by defective development of nerves involved in the movement of facial muscles. Because of this paralysis, people affected with this syndrome cannot make facial expressions of emotion. In addition, they have difficulty recognizing the emotional expressions of other people (Cole, 2001). Perhaps their inability to produce facial expressions of emotions makes it impossible for them to imitate the expressions of other people, and the lack of internal feedback from the motor system to the somatosensory cortex may make the task of recognition more difficult.

Mirror neurons are activated when an animal performs a particular behavior or when it sees another animal performing that behavior. These neurons are involved in learning to imitate the actions of others. These neurons, which are located in the ventral premotor cortex of the frontal lobe, receive input from the superior temporal sulcus and the posterior parietal cortex. This circuit is activated when we see another person perform a goal-directed action, and feedback from this activity helps us to understand what the person is trying to accomplish.

Carr et al. (2003) suggest that the mirror neuron system, which is activated when we observe facial movements of other people, provides feedback that helps us to understand how other people feel. In other words, the mirror neuron system may be involved in our ability to empathize with the emotions of other people.

Facial expressions of emotion are automatic and involuntary. It is not easy to produce a realistic facial expression of emotion when we do not really feel that way.

An Artificial Smile :

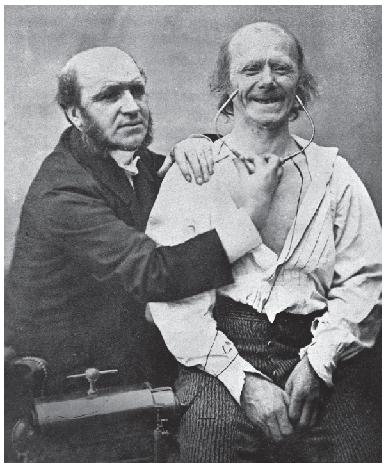

A nineteenth-century neurologist, Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne, found that genuinely happy smiles, as opposed to false smiles or social smiles people make when they greet someone else, involve contraction of a muscle near the eyes, the lateral part of the orbicularis oculi—now sometimes referred to as Duchenne’s muscle (Ekman, 1992; Ekman and Davidson, 1993).

The photograph shows Dr. Duchenne electrically stimulating muscles in the face of a volunteer, causing contraction of muscles around the mouth that become active during a smile. As Duchenne discovered, however, a true smile also involves muscles around the eyes.

As Duchenne put it, “The first [zygomatic major muscle] obeys the will but the second [orbicularis oculi] is only put in play by the sweet emotions of the soul; the . . . fake joy, the deceitful laugh, cannot provoke the contraction of this latter muscle”

The difficulty actors have in voluntarily producing a convincing facial expression of emotion is one of the reasons that led Constantin Stanislavsky to develop his system of method acting, in which actors attempt to imagine themselves in a situation that would lead to the desired emotion. Once the emotion is evoked, the facial expressions follow naturally (Stanislavsky, 1936).

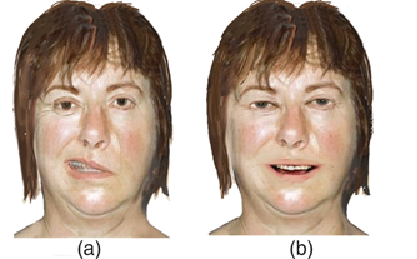

This observation is confirmed by two neurological disorders with complementary symptoms.

- The first, volitional facial paresis , is caused by damage to the face region of the primary motor cortex or to the fibers connecting this region with the motor nucleus of the facial nerve, which controls the muscles responsible for movement of the facial muscles. The patient cannot voluntarily move the facial muscles but will express a genuine emotion with those muscles. For example, this figure shows a woman trying to pull her lips apart and show her teeth. Because of the lesion in the face region of her right primary motor cortex, she could not move the left side of her face. However, when she laughed, both sides of her face moved normally.

**volitional facial paresis **:

(a) A woman with volitional facial paresis caused by a right hemisphere lesion tries to pull her lips apart and show her teeth. Only the right side of her face responds. (b) The same woman shows a genuine smile.

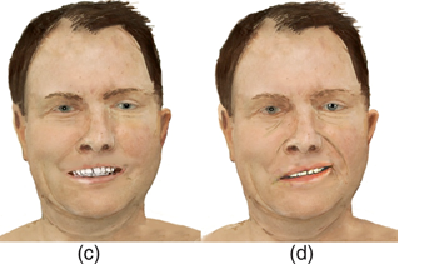

In contrast, emotional facial paresis is caused by damage to the insular region of the prefrontal cortex, to the white matter of the frontal lobe, or to parts of the thalamus. This system joins the system responsible for voluntary movements of the facial muscles in the medulla or caudal pons. People with this disorder can move their face muscles voluntarily but do not express emotions on the affected side of the face. The left figure shows a man pulling his lips apart to show his teeth, which he had no trouble doing. The right figure shows him smiling; as you can see, only the left side of his mouth is raised. He had a stroke that damaged the white matter of the left frontal lobe. These two syndromes clearly indicate that different brain mechanisms are responsible for voluntary movements of the facial muscles and automatic, involuntary expression of emotions involving the same muscles.

emotional facial paresis:

(c) A man with emotional facial paresis caused by a left-hemisphere lesion shows his teeth. (d) The same man is smiling. Only the left side of his face responds.

As we saw earlier, the right hemisphere plays a more significant role in recognizing emotions in the voice or facial expressions of other people—especially negative emotions. The same hemispheric specialization appears to be true for expressing emotions.

When people show emotions with their facial muscles, the left side of the face usually makes a more intense expression.

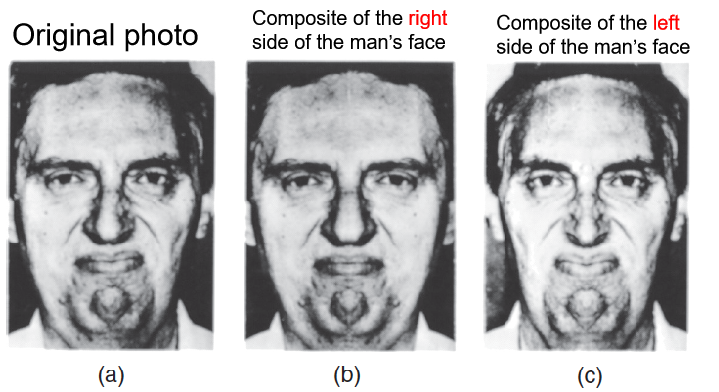

For example, Sackeim and Gur (1978) cut photographs of people who were expressing emotions into right and left halves, prepared mirror images of each of them, and pasted them together, producing so-called chimerical faces (from the mythical Chimera, a fire-breathing monster, part goat, part lion, and part serpent). They found that the left halves were more expressive than the right ones. Because motor control is contralateral, the results suggest that the right hemisphere is more expressive than the left.

We saw in earlier that amygdala plays a special role in emotional responses.

- Amygdala is involved in the recognition of other people’s facial expression of emotions.

Amygdala is not involved in the expression of facial emotions

Anderson and Phelps (2000) reported the case of S. P., a 54-year-old woman whose right amygdala was removed to treat a serious seizure disorder. Because of a preexisting lesion of the left amygdala, the surgery resulted in a bilateral amygdalectomy. After the surgery, S. P. lost the ability to recognize facial expressions of fear, but she had no difficulty recognizing individual faces, and she could easily identify male and female faces and accurately judge their ages. What is particularly interesting is that the amygdala lesions did not impair S. P.’s ability to produce her own facial expressions of fear. She had no difficulty accurately expressing fear, anger, happiness, sadness, disgust, and surprise. By the way, when she saw a photograph of herself showing fear, she could not tell what emotion her face had been expressing.

三、Feelings of Emotions

So far, we have examined two aspects of emotions:

- the organization of patterns of responses that deal with the situation that provokes the emotion;

- the communication of emotional states with other members of the species.

The final aspect of emotion to be examined in this chapter is the subjective component: feelings of emotion.

William James (1842–1910), an American psychologist, and Carl Lange (1834–1900), a Danish physiologist, independently suggested similar explanations for emotion, which most people refer to collectively as the James-Lange theory (James, 1884; Lange, 1887).

James-Lange’s theory of emotion that suggests that :

- Behaviors and physiological responses are directly elicited by situations;

- Feelings of emotions are produced by feedback from these behaviors and responses.

Own emotional feelings are based on what we find ourselves doing and on sensory feedback we receive from the activity of our muscles and internal organs.

- e.g. When we find ourselves trembling and feeling queasy, we experience fear.

- Where feelings of emotions are concerned, we are self-observers.

The James-Lange Theory

James says that our own emotional feelings are based on what we find ourselves doing and on the sensory feedback we receive from the activity of our muscles and internal organs.

- This schematic diagram indicates that an event in the environment triggers behavioral, autonomic, and endocrine responses. Feedback from these responses produces feelings of emotions.

1. Feeling first or response first?

James’s description of the process of emotion might strike you as being at odds with your own experience.

Many people think that they experience emotions directly, internally. They consider the outward manifestations of emotions to be secondary events.

But have you ever found yourself in an unpleasant confrontation with someone else and discovered that you were trembling, even though you did not think that you were so bothered by the encounter? Or did you ever find yourself blushing in response to some public remark that was made about you? Or did you ever find tears coming to your eyes while you watched a film that you did not think was affecting you? What would you conclude about your emotional states in situations like these? Would you ignore the evidence from your own physiological reactions?

Feedback from Simulated Emotions

A particular set of muscles—those of the face—helps us to communicate our emotional state to other people.

Several experiments suggest that feedback from the contraction of facial muscles can affect people’s moods and even alter the activity of the autonomic nervous system.

Ekman and his colleagues (Ekman, Levenson, and Friesen, 1983; Levenson, Ekman, and Friesen, 1990) asked subjects to move particular facial muscles to simulate the emotional expressions of fear, anger, surprise, disgust, sadness, and happiness. They did not tell the subjects what emotion they were trying to make them produce, but only what movements they should make.

For example, to simulate fear, they told the subjects, “Raise your brows. While holding them raised, pull your brows together. Now raise your upper eyelids and tighten the lower eyelids. Now stretch your lips horizontally.” (These movements produce a facial expression of fear.) While the subjects made the expressions, the investigators monitored several physiological responses controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

The simulated expressions did alter the activity of the autonomic nervous system. In fact, different facial expressions produced somewhat different patterns of activity. For example, anger increased the heart rate and skin temperature, fear increased the heart rate but decreased skin temperature, and happiness decreased the heart rate without affecting skin temperature.

Why should a particular pattern of movements of the facial muscles cause changes in mood or in the activity of the autonomic nervous system?

Perhaps the connection is a result of experience; in other words, perhaps the occurrence of particular facial movements along with changes in the autonomic nervous system leads to classical conditioning, so that feedback from the facial movements becomes capable of eliciting the autonomic response—and a change in perceived emotion.

Or perhaps the connection is innate. As we saw earlier, the adaptive value of emotional expressions is that they communicate feelings and intentions to others. The research presented earlier in this chapter on the role of mirror neurons and the somatosensory cortex suggests that one of the ways we recognize the feelings of others is through unconscious imitation.

A study by Lewis and Bowler (2009) found that interfering with muscular movement associated with a particular emotion decreased people’s ability to experience that emotion.

Injections of a very dilute solution of botulinum toxin (Botox) into facial muscles can reduce wrinkling of the skin caused by chronic contraction of facial muscles. Lewis and Bowler studied people who had been treated with injections of Botox into the corrugator muscle, whose contraction is responsible for a large part of the facial expression of frowning, which is associated with negative emotions. They found that these people showed significantly less negative mood, compared with people who had received other forms of cosmetic treatment. These results, like those described earlier in this subsection, suggest that feedback from a person’s facial expressions can affect his or her mood.

- Facial musculation not only express but regulates mood states.

Damasio et al. (2000)

A functional imaging study by Damasio et al. (2000) asked people to recall and try to re-experience past episodes from their lives that evoked feelings of sadness, happiness, anger, and fear. The investigators found that recalling these emotions activated the subjects’ somatosensory cortex and upper brain stem nuclei involved in control of internal organs and detection of sensations received from them. These responses are certainly compatible with James’s theory.

Summary

Emotions as Response Patterns

- Fear : Amygdala (central nucleus)

- Conditioned emotional response: Amygdala (lateral nucleus)

- Extinction of conditioned emotional response : ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)

- Anger, Aggression, and Impulse Control:

- impulsive violence is a consequence of faulty emotional regulation: Serotonin, vmPFC

Communication of Emotions

Facial Expression of Emotions: Innate Responses

Neural Basis of the Communication of Emotions: Recognition

Neural Basis of the Communication of Emotions: Expression

Feelings of Emotions

The James-Lange Theory

Feedback from Simulated Emotions