L7 Reproductive Behavior

Reproductive behaviors constitute the most important category of social behaviors, because without them, most species would not survive

Reproductive behaviors include:

- courting 讨好

- mating

- parental behavior 亲代行为

- most forms of aggressive behaviors 大多数攻击性行为的形式

Reproductive behaviors are the most striking categories of sexually dimorphic behaviors, that is, behaviors that differ in males and females (di + morphous, “two forms”).

sexually dimorphic behavior 性二态行为

- A behavior that has different forms or that occurs with different probabilities or under different circumstances in males and females.

一、Sextual behavior

Sex as a Form of Motivation

Sex is a motivated behavior like hunger.

But theorists have had difficulty categorizing sex with other physiological drives because it does not fit the pattern of a homeostatic tissue need. If you fail to eat or if you cannot maintain body temperature within reasonable limits, you will die. But no harm will come from forgoing sex;

- sex ensures the survival of the species but not of the individual

There are, however, several similarities with other drives like hunger and thirst. They include arousal and satiation, the involvement of hormones, and control by specific areas in the brain.

How is sex like and unlike other drives?

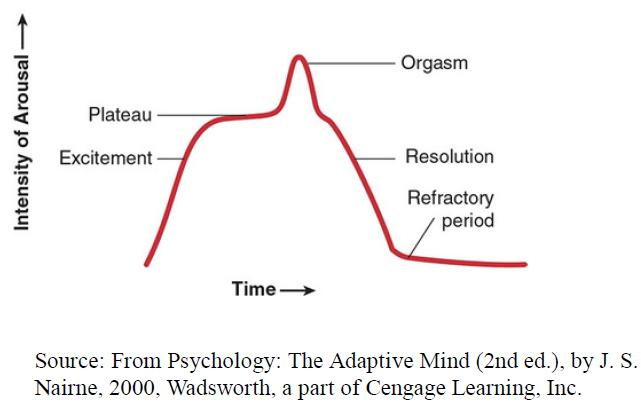

- The excitement phase is a period of arousal and preparation for intercourse.

- During the plateau phase, the increase in sexual arousal levels off.

- Orgasm is similar to the pleasure one feels after eating or when warmed after a deep chill, but it is unique in its intensity.

- The resolution that follows is reminiscent of the period of quiet following return to homeostasis with other drives.

- After orgasm, males have a refractory phase, during which they are unable to become aroused or have another orgasm for minutes, hours, or even days, depending on the individual and the circumstances

When comparing the sex drive with other kinds of motivation, the male refractory period has an interesting parallel with sensory-specific satiety, e.g. the Coolidge effect.

According to a popular but probably questionable story, President Coolidge and his wife were touring a farm when Mrs. Coolidge asked the farmer whether the flurry of sexual activity among the chickens was the work of one rooster. The farmer answered yes, that the rooster copulated dozens of times each day, and Mrs. Coolidge said, “You might point that out to Mr. Coolidge.” President Coolidge, so the story goes, then asked the farmer, “Is it a different hen each time?” The answer again was yes. “Tell that to Mrs. Coolidge,” the president replied.

Whether the story is true or not, the Coolidge effect—The restorative effect of introducing a new female sex partner to a male that has apparently become “exhausted” by sexual activity.

As important as sex is to humans, it is ironic that so much of what we know about the topic comes from the study of other species.

- One reason is that research into human sexual behavior was for a long time considered off-limits, and funding was hard to come by.

- Another reason is that sexual behavior is more “accessible” in nonhuman animals; rats have sex as often as 20 times a day and are not at all embarrassed to perform in front of the experimenter.

- In addition, we can manipulate their sexual behavior in ways that would be considered unethical with humans.

Hormonal control in particular is more often studied in animals because hormones have a clearer role in animal sexual behavior.

Hormonal Control of Sexual Behavior

Method: castration

- Castration: removal of the gonads (testes or ovaries), is one technique used to study hormonal effects because it removes the major source of sex hormones; castration results in a loss of sexual motivation in nonhuman mammals of both sexes. Sexual behavior may not disappear completely, because the adrenal glands continue to produce both male and female hormones, though at a lesser rate than the gonads. The time course of the decline is also variable, ranging from a few weeks to five months in male rats (J. M. Davidson, 1966)

- Androgens(雄激素): are referred to as male sex hormones responsible for a number of male characteristics and functions.

- There are two main types of androgens namely, adrenal androgens(肾上腺雄激素) and testicular androgens(睾丸雄激素)

- Androgen activity is also present in females but in a very low scale. Androgens in females are involved in premature uterine contractions and help to create a balance of hormones.

- Testosterone(睾酮): the main androgen, which is the testicular androgen and is produced by the testes.

- Estrogen(Oestrogen): are the main hormone that involves in imparting sexual characteristics to females. Estrogen is mainly secreted by the ovaries(卵巢). Similar to androgens, estrogen is also present in males but in very fewer quantities.

1. What are the Similarities Between Androgen and Estrogen?

- Both Androgen and Estrogen hormones are steroid hormones(类固醇激素).

- Both Androgen and Estrogen hormones are present in males and females.

- Deficiency in both Androgen and Estrogen hormones can lead to altered sexual characteristics and functions in males and females.

- Both Androgen and Estrogen hormones are involved in the reproduction process and in the development of secondary sexual characteristics.

- Both Androgen and Estrogen hormones signal transduction pathways involve binding to the hormone response element of the DNA via the formation of the hormone – receptor complex.

2. What is the Difference Between Androgen and Estrogen?

| Androgen | Estrogen | |

|---|---|---|

| Androgen is the sex hormone that Is found In high amounts in males that are responsible for male charactenistics and reproduction | Estrogen is the sex hormone that is found in high levels in females which is responsible for the female characteristics and reproduction | |

| Types | There are two major types of androgens namely, adrenal androgens(肾上腺雄激素) and testicular androgens(睾丸雄激素) | There are three main types of estrogen namely estradiol(雌二醇)estrone(雌酮), estriol(雌三醇). |

| Function | Androgen imparts male sexual characteristics and aids in the reproduction process | Estrogen imparts female sexual characteristics and aids in the reproduction process, pregnancy, delivery of the baby and the process of menstruation and menopause |

3. The Role of Testosterone

The effects of castration indicate that testosterone is necessary for male sexual behavior, but the amount of testosterone required appears to be minimal; men with very low testosterone levels can be as sexually active as other men (Raboch & Stárka, 1973)

Frequency of sexual activity does vary with testosterone levels within an individual, but the testosterone increases appear to be the result of sexual activity rather than the cause.

For example, testosterone levels are high in males at the end of a period in which intercourse occurred, not necessarily before

4. The Role of Estrogen

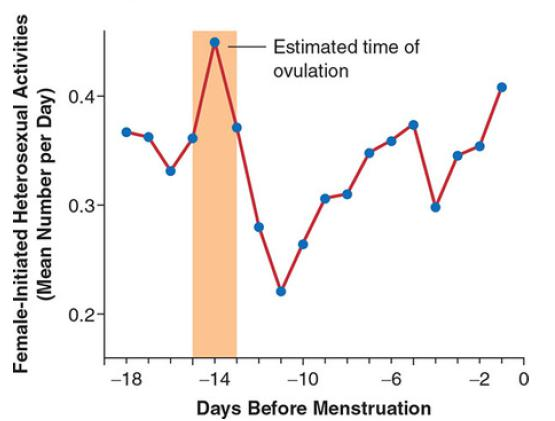

estrus, a period when the female is ovulating, sex hormone levels are high, and the animal is said to be in heat.

- Activity initiated by women peaks around the middle of the menstrual cycle, which is when ovulation occurs

Brain Structures and Neurotransmitters

Sexual activity, like other drives and behaviors, involves a network of brain structures. This almost seems inevitable, because sexual activity involves reaction to a variety of stimuli, activation of several physiological systems, postural and movement responses, a reward experience, and so on

We do not understand yet how the sexual network operates as a whole, but we do know something about the functioning of several of its components.

In this section, you will see some familiar terms, the names of hypothalamic structures. This illustrates an important principle of brain functioning, that a particular brain area, even a very small one, often has multiple functions

Two areas are important in sexual behavior in both sexes, the medial preoptic area(内侧视前区) of the hypothalamus and the medial amygdala(内侧杏仁核)

- The medial preoptic area (MPOA) is one of the more significant brain structures involved in male and female sexual behavior.

- Stimulation of the MPOA increases copulation in rats of both sexes, and the MPOA is active when they copulate spontaneously.

- The MPOA appears to be more responsible for performance than for sexual motivation; when it was destroyed in male monkeys, they no longer tried to copulate, but instead they still have sexual motivation.

- The medial amygdala also contributes to sexual behavior in rats of both sexes. The amygdala is involved not only in sexual behavior but also in aggression and emotions. The medial amygdala is active while rats copulate, and stimulation causes the release of dopamine in the MPOA .

- The medial amygdala’s role apparently is to respond to sexually exciting stimuli, such as the presence of a potential sex partner.

Recall: Neural Control of Slow-Wave Sleep

But what controls the activity of the arousal neurons? What causes this activity to fall, thus putting us to sleep? The preoptic area , a region of the anterior hypothalamus, is the brain region most involved in the initiation of sleep. The preoptic area contains neurons whose axons form inhibitory synaptic connections with the brain’s arousal neurons. When our preoptic neurons (let’s call them sleep neurons) become active, they suppress the activity of our arousal neurons, and we fall asleep (Saper, Scammell, and Lu, 2005).

Ventrolateral preoptic area (vlPOA)

- Group of GABAergic neurons in the preoptic area whose activity suppresses alertness and behavioral arousal and promotes sleeps

There are other areas that are involved in sexual behavior but only in the behaviors of a single sex.

Two other hypothalamic structures are also important. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN,室旁核) is important for male sexual performance and, particularly, for penile erections.

The ventromedial hypothalamus is active in females during copulation, and its destruction reduces the female’s responsiveness to a male’s advances.(降低了求爱反应)

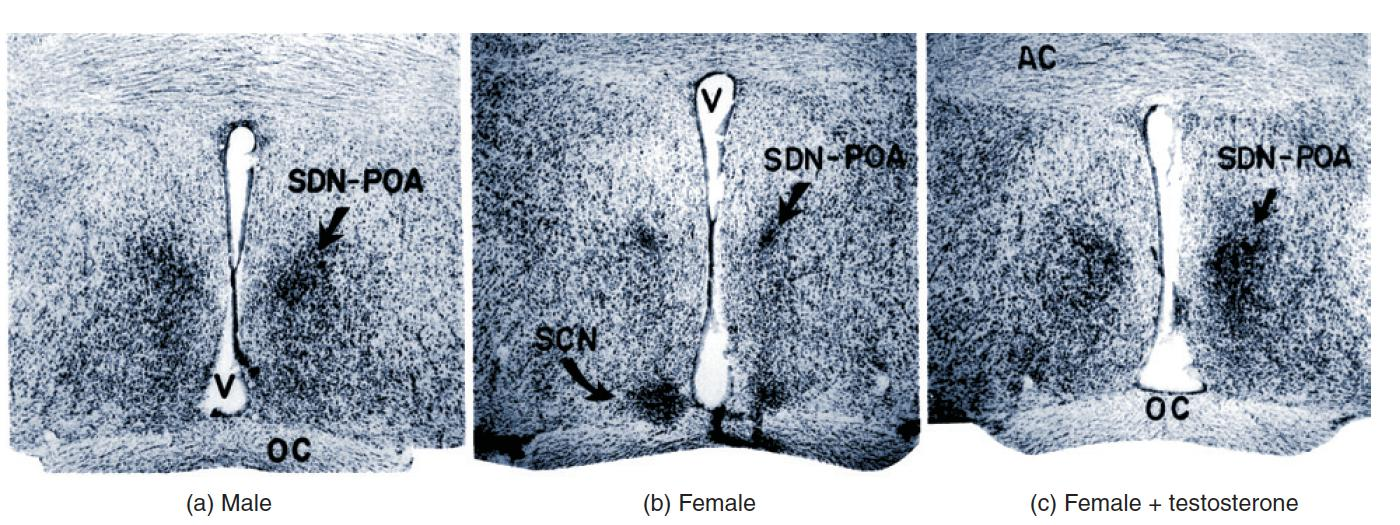

1. Preoptic Area of the Rat Brain

- These photomicrographs of sections through the preoptic area of a rat brain show (a) normal male, (b) normal female, and (c) androgenized female, given an injection of testosterone shortly after birth.

- SDNPOA = sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area;

- OC = optic chiasm;

- V = third ventricle; 第三脑室

- SCN = suprachiasmatic nucleus; 视交叉上核

- AC = anterior commissures 前连合

For obvious reasons, we know much less about the brain structures involved in human sexual behavior. Functional MRI (fMRI) recording during masturbation has confirmed the involvement of the medial amygdala and PVN in human sexual activity.

- PVN neurons are known to secrete the hormone/neuromodulator oxytocin(催产素), which contributes to male and female orgasm and the intensity of its pleasure. (性高潮以及快感强度)

Sexual behavior involves several neurotransmitters, but dopamine has received the most attention.

Dopamine level increases in the nucleus accumbens during sexual activity, and stimulation of the medial amygdala releases dopamine in the MPOA. (在性活动中,伏隔核中多巴胺水平增加,刺激内侧杏仁核释放MPOA中的多巴胺)

Dopamine activity in the MPOA contributes to sexual motivation in males and females of several species. In males, dopamine is critical for sexual performance.

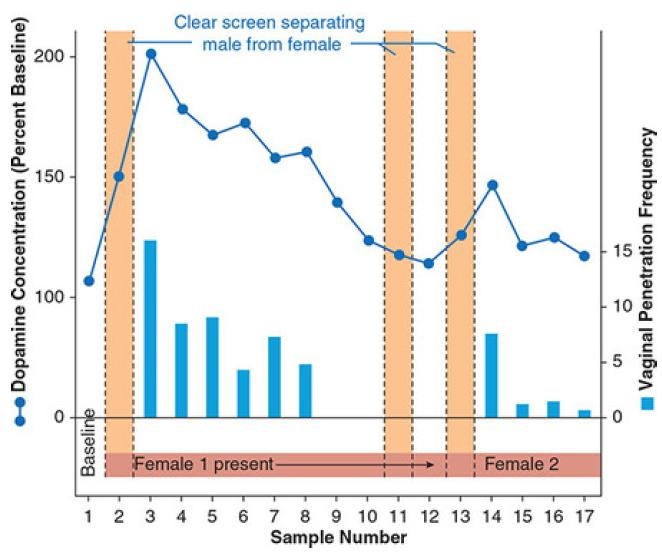

It increased in the male rat’s nucleus accumbens in the presence of a female, dropped back to baseline as interest waned, and then increased again with a new female. The changes occurred even when the male and female were separated by a clear panel, so the dopamine level reflects the male’s interest rather than the effects of sexual behaviors.

2. Dopamine Levels in the Nucleus Accumbens During the Coolidge Effect.

- Activity was recorded until the male lost interest in Female 1; then Female 2 was presented. During the periods represented by the orange bar, the female was separated from the male by a clear screen. The line graph shows dopamine levels

Ejaculation is also accompanied by serotonin increases in the lateral hypothalamus(下视丘外核), which apparently contributes further to the refractory period.

Injecting a drug that inhibits serotonin reuptake into the lateral hypothalamus increases the length of time before male rats will attempt to copulate again and their ability to ejaculate when they do return to sexual activity

- Humans take serotonin reuptake blockers to treat anxiety and depression, and they often complain that the drugs interfere with their ability to have orgasms

Gender-Related Aggressive and Bonding Behaviors

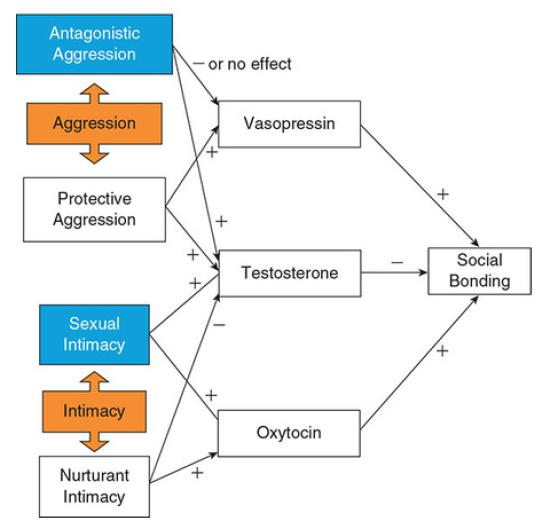

An interesting model for the regulation of gender-related aggressive and bonding behaviors has been proposed in the steroid/peptide theory of social bonds (van Anders, Goldey, & Kuo, 2011).

According to this theory, the balance among testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin determine behaviors such as aggression and intimacy.

- As you probably guessed, a high testosterone level in either sex increases aggression, but it also impairs the formation of close social bonds

Oxytocin (involved in muscle contractions of sexual tissue and in social bonding) and vasopressin (a potent neuromodulator of brain activity) modulate the form of intimacy and aggression.

- Antagonistic aggression(对抗性攻击) (which includes social dominance, partner acquisition, and defense of partners and territory) is seen in those with low levels of vasopressin

- Protective aggression(保护性攻击) (such as defending children or partners) is seen in those with high levels of vasopressin.

Intimacy increases oxytocin, but its interaction with testosterone levels determines whether that intimacy is sexual (if testosterone is high) or nurturing (if testosterone is low)

Therefore, testosterone levels determine the relative amount of competitive versus nurturing behaviors an individual expresses, whereas oxytocin determines the relative amount of social bonding versus social isolation

1. The Steroid/Peptide Theory of Social Bonds

Source: From “The Steroid/Peptide Theory of Social Bonds: Integrating testosterone and peptide responses for classifying social behavioral contexts,” by S. M. van Anders, K. L. Goldey, & P. X. Kuo. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(9)

In the theory, three important hormones interact to detemine not only the stength of bonds with others but also the characterists of those relationship.

First, testosterone levels increase aggression and decrease social bonding, while vasopressin levels modify the form of aggresson.

Low levels of vasopression cause attack-type behavior (antagonistic), while high levels of vassopression increase protective behaviors that result in stronger social bonds with others

Oxytocin regulates the level of intimacy(亲密程度) and interacts with testosterone as well.

- Low testosterone with high oxytocin is correlated with more helpful, supporting intimacy and stronnger social bonds, where high levels of both hormones lead to more sexualized relationships with others.

- Therefore, the strongest social bonds result from high levels of oxytocin and vasopressin and low levels of testosterone.

More about oxytocin: Of Love, Bonding, and Empathy

Sexual activity releases the neuropeptides oxytocin and vasopressin, which are likewise required for bonding to take place. Either can facilitate bonding in males or females, but oxytocin is more effective with females and vasopressin with males.

So does any of this apply to humans, who are also monogamous (more or less)? The most apparent parallel involves oxytocin.

Oxytocin not only facilitates bonding but also causes smooth muscle contractions, such as those involved in orgasm and in milk ejection during breastfeeding.

Oxytocin also contributes to social recognition, which is necessary for developing mate preferences.

Male mice without the oxytocin gene fail to recognize females from one encounter to the next, and human males are better at recognizing previously seen photos of women after receiving oxytocin.

Men given oxytocin also had more activity in the nucleus accumbens while viewing photos of their partners, and they increased their ratings of their partners’ attractiveness, but not of other women they knew.

Oxytocin’s bonding effects are not limited to mates and sex partners. Mother-infant bonding is correlated with oxytocin levels during pregnancy and following birth, and a gene for the oxytocin receptor is related to parenting sensitivity.

Oxytocin also apparently explains empathetic behavior in prairie voles. Though we can’t speculate about what the rodents are “feeling,” they respond to a cagemate’s earlier, unobserved stress with increased grooming, and they match the cagemate’s fear response, anxiety-related behaviors, and corticosterone increase. Consoling behavior did not occur if the animals received an infusion of an oxytocin receptor antagonist into the lateral ventricles.

- Prairie voles are a rare exception among mammals; they mate for life (to form pairs and stay together throughout life), and if they lose a mate they rarely take another partner.

- The bonding process begins with the release of dopamine in reward areas during mating. If dopamine activity is blocked by a receptor antagonist, partner preference fails to develop.

Odors, Pheromones, and Sexual Attraction

Sexual behavior results from the interplay of internal conditions, particularly hormone levels, with external stimuli. Sexual stimuli can be anything from brightly colored plumage or an attractive body shape to particular odors. Here we will examine the role of odors and pheromones in sexual attraction.

Hormones transmit messages from one part of the body (the secreting gland) to another (the target tissue). Another class of chemicals, called pheromones , carries messages from one animal to another. Some of these chemicals, like hormones, affect reproductive behavior. Karlson and Luscher (1959) coined the term, from the Greek pherein, “to carry,” and horman, “to excite.” Pheromones are released by one animal and directly affect the physiology or behavior of another. In mammalian species most pheromones are detected by means of olfaction.

Pheromone

- A chemical released by one animal that affects the behavior or physiology of another animal; usually smelled or tasted.

Pheromones can affect reproductive physiology or behavior. First, let us consider the effects on reproductive physiology.

- When groups of female mice are housed together, their estrous cycles slow down and eventually stop(发情期减慢并最终停止). This phenomenon is known as the Lee-Boot effect (van der Lee and Boot, 1955).

- If groups of females are exposed to the odor of a male (or of his urine), they begin cycling again, and their cycles tend to be synchronized(开始发情周期且周期趋于同步). This phenomenon is known as the Whitten effect (Whitten, 1959).

- The Vandenbergh effect (Vandenbergh, Whitsett, and Lombardi, 1975) is the acceleration of the onset of puberty in a female rodent caused by the odor of a male(雌性因雄性啮齿动物的气味而提前青春期的到来)

- Both the Whitten effect and the Vandenbergh effect are caused by a group of compounds that are sent only in the urine of intact adult males (Ma, Miao, and Novotny, 1999; Novotny et al., 1999); the urine of a juvenile or castrated male has no effect. Thus, the production of the pheromone requires the presence of testosterone

Lee-Boot effect

- The slowing and eventual cessation of estrous cycles in groups of female animals that are housed together; caused by a pheromone in the animals’ urine; first observed in mice.

Whitten effect

- The synchronization of the menstrual or estrous cycles of a group of females, which occurs only in the presence of a pheromone in a male’s urine.

Vandenbergh effect

- The earlier onset of puberty seen in female animals that are housed with males; caused by a pheromone in the male’s urine; first observed in mice.

Bruce effect

- Termination of pregnancy caused by the odor of a pheromone in the urine of a male other than the one that impregnated the female; first identified in mice.

The Bruce effect (Bruce, 1960a, 1960b) is a particularly interesting phenomenon: When a recently impregnated female mouse encounters a normal male mouse other than the one with which she mated, the pregnancy is very likely to fail. This effect, too, is caused by a substance secreted in the urine of intact males—but not of males that have been castrated. Thus, a male mouse that encounters a pregnant female is able to prevent the birth of infants carrying another male’s genes and subsequently impregnate the female himself. This phenomenon is advantageous even from the female’s point of view. The fact that the new male has managed to take over the old male’s territory indicates that he is probably healthier and more vigorous, and therefore his genes will contribute to the formation of offspring that are more likely to survive

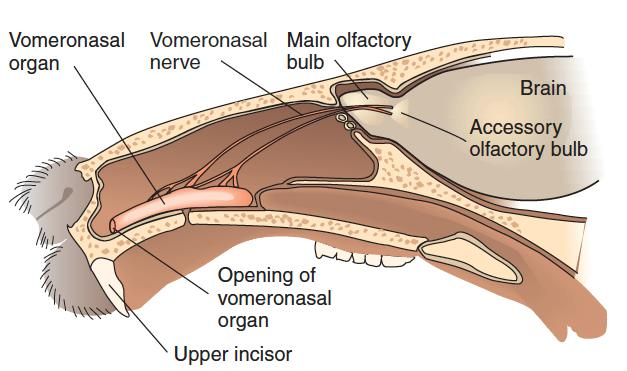

- The Rodent Accessory Olfactory System

Detection of odors is accomplished by the olfactory bulbs, which constitute the primary olfactory system. However, many of the effects that pheromones have on reproductive cycles are mediated by another sensory organ—the vomeronasal organ (VNO) —which consists of a small group of sensory receptors arranged around a pouch connected by a duct to the nasal passage.

The vomeronasal organ, which is present in all orders of mammals except for cetaceans (whales and dolphins), projects to the accessory olfactory bulb , located immediately behind the olfactory bulb.

- Removal of the accessory olfactory bulb disrupts the LeeBoot effect, the Whitten effect, the Vandenbergh effect, and the Bruce effect; thus, the vomeronasal system is essential for these phenomena.

Besides having effects on reproductive physiology, some pheromones directly affect behavior.

发情期异性吸引

Pheromones can be very powerful, as you know if your yard has ever been besieged by all the male cats in the neighborhood when your female cat was “in heat.”

The female gypsy moth can attract males from as far as two miles away (Hopson, 1979).

亲缘识别

Pheromones provide cues for kin recognition in animals, influence cycling of sexual receptivity in female mice, initiate aggression in both males and females, and trigger maternal behavior in adults and suckling in infants (Wysocki & Preti, 2004).

Some male pheromones that attract females are detected by the main olfactory system.

For example, Mak et al. (2007) found that the odor of soiled bedding taken from the cage of a male mouse activated neurons in the main olfactory system and hippocampus. The odor even stimulated neurogenesis (production of new neurons); Mak and her colleagues found new neurons in the olfactory bulb and hippocampus. Moreover, bedding from cages of dominant males stimulated neurogenesis more effectively than did bedding from subordinate males

Do pheromones play a role in human behavior?

- In spite of the eagerness with which the media and fragrance industry have embraced the topic, the best answer appears to be “maybe . . . maybe not.” We certainly don’t see pheromones controlling sexual behavior as powerfully as they do in animals; in fact, the best candidate for pheromone control of human behavior is the sucking and searching movements in infants in response to breast odors of a nursing woman (Wyatt, 2016; Wysocki & Preti, 2004)

二、The Biological Determination of Sex

Sex is the term for the biological characteristics that divide humans and other animals into the categories of male and female.

Gender refers to the behavioral characteristics associated with being male or female.

For our purposes, it will be useful to make two further distinctions: Gender role is the set of behaviors society considers appropriate for people of a given biological sex, whereas gender identity is the person’s subjective feeling of being male or female.

The term sex cannot be used to refer to all these concepts, because the characteristics are not always consistent with each other. Thus, classifying a person as male or female can sometimes be difficult.

You might think that the absolute criterion for identifying a person’s sex would be a matter of chromosomes, but you will soon see that it is not that simple.

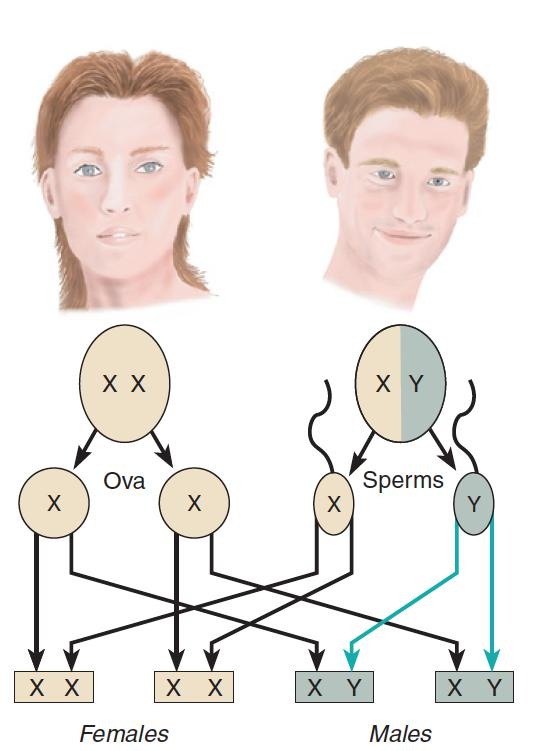

What makes a person male or female?

- The gender of the offspring depends on whether the sperm cell that fertilizes the ovum carries an X or a Y chromosome.

Men and women differ in many ways: Their bodies are different, parts of their brains are different, and their reproductive behaviors are different.

Are all these differences encoded on the tiny Y chromosome, the sole piece of genetic material that distinguishes males from females? The answer is no.

The X chromosome and the twenty-two nonsex chromosomes found in the cells of both males and females contain all the information needed to develop the bodies of either sex

Exposure to sex hormones, both before and after birth, is responsible for our sexual dimorphism(两性异形)

What the Y chromosome does control is the development of the glands that produce the male sex hormones.

In the absence of a Y chromosome (and SRY gene), the primitive gonads of the XX fetus develop into ovaries. The ovaries won’t begin producing estrogens until later, but in humans default sex is female, and the uterus, vagina, clitoris, and labia will all develop without benefit of hormones. You should understand that it is not entirely accurate to speak of hormones as being “male” or “female.” The testes and ovaries each secrete both androgens and estrogens, although in differing amounts; the adrenal glands of the kidney also secrete small amounts of both kinds of hormones.

The hormonal effects we have been discussing are called organizing effects.(组织效应)

- Organizing effects mostly occur prenatally and shortly after birth; they affect structure and are lifelong in nature. Organizing effects are not limited to the reproductive organs; they include sexspecific changes in the brains of males and females as well, at least in nonhuman mammals.

Activating effects(激活效应) can occur at any time in the individual’s life; they are reversible changes that can come and go as hormone levels change. Some of the changes that occur during puberty are examples of activating effects.

Gender-Related Behavioral and Cognitive Differences

In his popular book Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, John Gray (1992) said that men and women communicate, think, feel, perceive, respond, love, and need differently, as if they are from different planets and speaking different languages. How different are men and women? This question is not easily answered, but it is not for lack of research on the topic. The results of studies are often ambiguous and contradictory.

1. Demonstrated Male-Female Differences

Back in 1974, Eleanor Maccoby and Carol Jacklin reviewed more than 2,000 studies and concluded that the evidence firmly supported three differences in cognitive performance and one difference in social behavior:

- Girls have greater verbal ability than boys

- boys excel in visual-spatial ability,

- boys excel in mathematical ability

- boys are more aggressive than girls

Later research has supported these differences to some extent, but with qualifications.

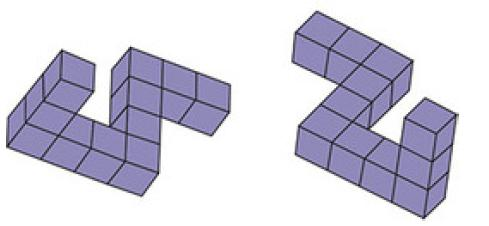

- First, there is considerable overlap between males and females in these characteristics. Second, the differences are rather specific. For example, females excel in verbal fluency and writing but not in reading comprehension or vocabulary (Eagly, 1995; Hedges & Nowell, 1995), and male spatial performance exceeds females’ most on tasks requiring mental rotation of a three dimensional object and less on other spatial tasks (Hyde, 1996).

- More significantly, the differences have narrowed during the ensuing four-plus decades, particularly for the cognitive abilities.

A Spatial Rotation Task

People are presented several pairs of drawings like these and alsked whether the first could be rotated so taht it looks like the second. Males are typically better at this kind of task than females.

- The Answer is No in this case!

How do we explain the differences in verbal and spatial abilities and in aggression?

Males who produce low amounts of testosterone during the developmental years are impaired later in spatial ability, and testosterone replacement in older men improves their spatial functioning.

xIndividuals born men who take estrogens because they identify as females (transgender women) increase their scores on verbal fluency tasks, but they lose spatial performance; transgender men taking testosterone lose verbal ability but improve in spatial performance

Men kill 30 times as often as women do, and testosterone is usually blamed for this difference. However, whether testosterone is the cause or the result of aggression is questioned because a variety of studies show, for example, that winning a sports competition increases testosterone and losing decreases it

Aggression in males is partly inheritable; genetic effects account for about half the variance in aggression, and aggression is moderately correlated in identical twins even when they are reared apart. The source of aggression is a complex subject

Differences in brain functioning are also cited as bases for gender differences. Jerre Levy (1969) hypothesized that women outperform men on verbal tests because they are able to use both hemispheres of the brain to solve verbal problems rather than mostly the left hemisphere. This idea has obviously been controversial; there has been some support from fMRI studies, but there have also been negative findings, and a meta-analysis of fMRI studies during language tasks found no lateralization differences between males and females (Sommer, Aleman, Bouma, & Kahn, 2004).

This doesn’t settle the issue, according to Harrington and Farias (2008), who claim that many fMRI studies are not as methodologically rigorous as they could be, and point out that gender differences should be expected only on some types of tasks. A more recent strategy has been to measure functional connectivity. Some support for Levy’s hypothesis comes from studies that found greater connectivity within hemispheres in males and greater connectivity between the hemispheres in females (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Tomasi & Volkow, 2012)

A meta-analysis of spatial performance did confirm gender differences, with males relying primarily on the right hemisphere and females showing no hemisphere preference (J. M. Vogel, Bowers, & Vogel, 2003).

Imaging studies indicate that men use parietal areas to perform spatial rotations, whereas women rely more on frontal areas (reviewed in Andreano & Cahill, 2009), and that men’s scores on the task are correlated with the amount of cortical surface in the parietal lobes (Koscik, O’Leary, Moser, Andreasen, & Nopoulos, 2009).

In an fMRI study, men performed a spatial memory task by activating the right hippocampus, whereas women relied on the left hippocampus and reported using a verbal strategy (Frings et al., 2006).

There are also several other indications that male and female brains work differently. Males and females have different patterns of brain activation during learning (Andreano & Cahill, 2009), pain (Naliboff et al., 2003), and stress (J. Wang et al., 2007).

Males are genetically more resistant to pain, and males and females respond differently to different pain medications (J. Bradbury, 2003).

Men are less affected by stress (Matud, 2004), and, males are more susceptible to autism, Tourette syndrome, and attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, whereas women are more likely to suffer from depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Research suggests that some of these differences may be due to male-female differences in expression of their genes

三、Biological Origins of Gender Identity Sexual Orientation

We use the acronym LGBT to describe the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. The first three letters (LGB) refer to sexual orientation. The ‘T’ refers to issues of gender identity

Gender identity is your own, internal, personal sense of being a man or a woman (or as someone outside of that gender binary)

Sexual orientation describes a person’s enduring physical, romantic, and/or emotional attraction to another person (for example: straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual).

Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, or bisexual

Biological Origins of Gender Identity

Individuals who believe they have been born into the wrong sex are referred to as transgender. They may dress and live as the other sex, take hormones to feminize or masculinize their bodies, or undergo surgery for sex reassignment.

It is estimated that 0.1%–0.5% of people in the United States and the United Kingdom have taken some steps to transition to the other sex (Gates, 2011).

Distress that people may feel due to the perception that their sex does not match their gender is called gender dysphoria(性别认同障碍).

Gender dysphoria is estimated to occur in 0.005%–0.014% of adult males and in 0.002%–0.003% of adult females (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Specific genes that have been identified are alleles of the CYP17 gene and the AR gene

- CYP17 is a candidate gene of FtM transsexualism, it increases testosterone levels in female-to-male transgender individuals (Bentz et al., 2008).

- AR reduces sensitivity to androgen in male-to-female transgender individuals (Hare et al., 2009).

- The researchers believe these genes lead to masculinization of the female brain and a failure to masculinize the male brain.

For decades, sex researchers have argued about what shapes an individual’s gender identity, with some believing it is formed in the first few years of life by a combination of rearing practices and genital appearance (Money & Ehrhardt, 1972) and others claiming that chromosomes and hormones are more important (M. Diamond, 1965).

Our earlier discussion of the effects of XY and XX chromosomes was the simple version of the sex-determination story; in reality, development sometimes takes an unexpected turn. As you will soon see, the results not only challenge our definition of what is male and what is female but also tell us a great deal about the influence of biology on gender

How could an individual’s genitals and brain develop at variance with each other?

They differentiate sexually at different times during gestation, the genitals during the first two months and the brain during the last half, presumably allowing them to fall under the influence of independent processes (Bao & Swaab, 2011).

Several studies suggest that the brains of transgender individuals have followed a different developmental path, finding that various brain structures are more like those of their identified sex than of their birth sex in size, shape, or patterning (reviewed in Saraswat et al., 2015)

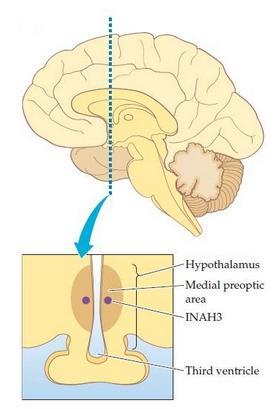

- The third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH3) is larger in men than in women and is thought to be the human counterpart of the sexually dimorphic nucleus. INAH3is believed to correspond to the sexually dimorphic nucleus in animals.

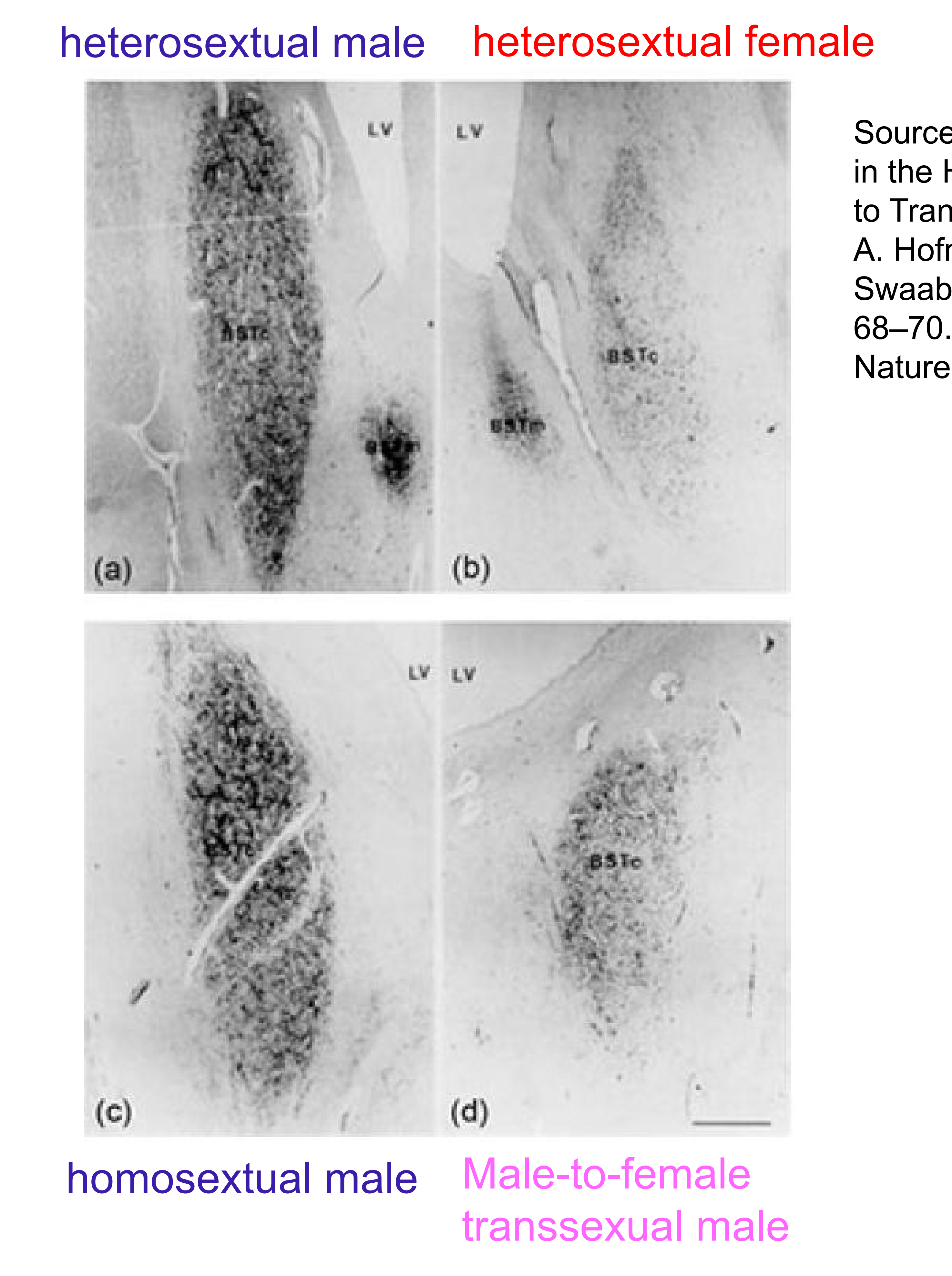

- INAH3 and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTc, which controls autonomic,neuroendocrine, and behavioral responses) are larger in males than in females, but they have been reported to be female sized in male-to-female transgender individuals (Garcia-Falgueras& Swaab, 2008; Kruijver et al., 2000; J. N. Zhou, Hofman, Gooren, & Swaab, 1995).

Representative images of the strained BSTc:

Female-typical brain responses have also been reported in male-to-female transgender individuals

- In a study with presumed pheromones, an androgen derivative found in male sweat (4, 16androstadien-3-one, or AND) activated the anterior hypothalamus, whereas an estrogen-like compound found in female urine (estratetraenol, or EST) did not (Berglund, Lindström, DhejneHelmy, & Savic, 2008).

- In a second study, when male-to-female transgender individuals viewed an erotic video, their pattern of brain responses resembled those of women rather than men (Gizewski et al., 2009). The studies are vulnerable to a variety of criticisms, however: Some, though not all, of the studies are potentially contaminated because the subjects were undergoing hormone treatment; studies have rarely been replicated, and results from attempts have been inconsistent; and “data-snooping” brain scans—measuring a large number of structures because the researcher doesn’t know what to look for— increases the probability of incorrectly identifying one of them as different, especially in the small samples that are typical of research on transgender individuals.

What is intersex?

Intersex is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male.The ones between male and female are often referred to as intersex conditions.

46 XY difference in sexual development (46 XY DSD), meaning that he had a typical number of chromosomes, including an X and a Y chromosome, but his sexual development was atypical for those chromosomes.

- e.g. Androgen insensitivity syndrome(雄激素不敏感综合征), a form of 46 XY DSD, is caused by a genetic absence of androgen receptors, which results in insensitivity to androgen

46 XX Difference in Sexual Development: A female fetus may be partially masculinized by excess androgen and by some hormone treatments during fetal development, resulting in 46 XX difference in sexual development

- e.g: congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH,先天性肾上腺增生症), which results from an enzyme defect that causes the individual’s adrenal glands to produce large amounts of androgen during fetal development and after birth until the problem is treated.

- CYP17A1 gene and account for approximately 1% of all cases of CAH

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientationis an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender (American Psychological Association, 2013). It is a complex trait that is shaped by multiple genes, biological, environmental, and sociocultural influences(Hamer, Rice, Risch, & Ebers, 1999).

1. Why is it difficult to measure sexual orientation rates?

It is difficult to estimate how many people are homosexual; the numbers vary from study to study and from one country to another, due to differences in definition and sampling methods, as well as reluctance to admit membership in a stigmatized group. In a review of nine studies, the average rate in the United States was 3.5%, with Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Norway ranging from 1.2% to 2.1% (Gates, 2011).

Interestingly, when Gallup asked Americans what percentage of the U.S. population they thought was gay or lesbian, the average answer was 23% (Newport, 2015). That response hasn’t changed significantly since 2002, in spite of increasing acceptance of homosexuality and access to greater information.

About 1% of people express no interest in sex at all

Research does not support the belief that gay men are necessarily feminine and lesbians are masculine; only about 44% of gays and 54% of lesbians fit those descriptions (Bell, Weinberg, & Hammersmith, 1981)

Even then, they usually identify with their biological sex, so gender role, gender identity, and sexual orientation are somewhat independent of each other and probably have different origins

2.The Social Influence Hypothesis

It has been argued that homosexuality arises from parental influences or is caused by early sexual experiences.

Bell and his colleagues (1981) expected to confirm these influences when they studied 979 gay and 477 heterosexual men. But they found no support for frequently hypothesized environmental influences, such as seduction by an older male or a dominant mother and a weak father.

3. Genetic and Epigenetic Influences

Twin and family studies provide the most documented evidence for a biological basis for sexual orientation. Homosexuality is seen two to seven times more often among the siblings of homosexuals than it is in the general population

(J. M. Bailey & Bell, 1993; J. M. Bailey & Benishay, 1993; Hamer, Hu, Magnuson, Hu, & Pattatucci, 1993)

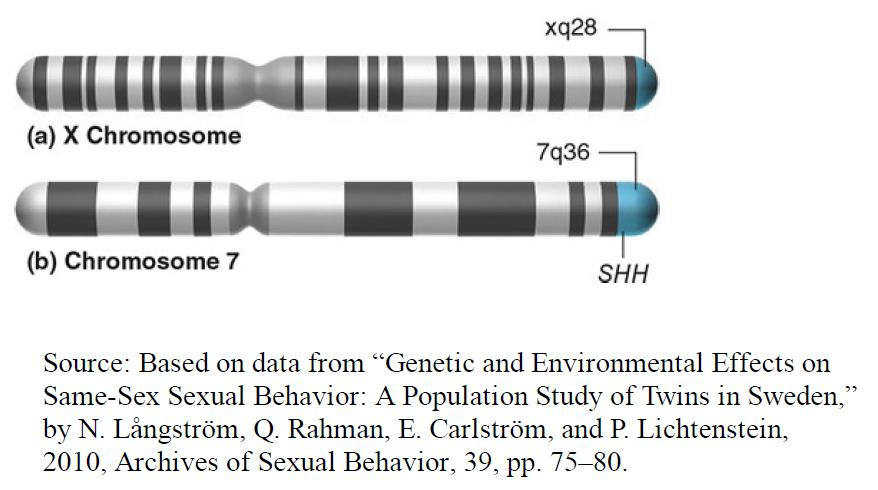

4. Possible Locations of Genes for Male Homosexuality

The search for specific genes has been frustrating, which is not uncommon when multiple genes are involved; because any number of combinations of the genes can produce the behavior, a particular gene can have a significant effect in one study and go undetected in the next.

The most successful research on male homosexuality has involved a stretch of DNA on the X chromosome. Dean Hamer and his associates (1993) focused their attention there because gay men have more gay relatives on the mother’s side of the family than on the father’s side, and the mother contributes only X chromosomes to her sons. They found that 64% of the pairs of gay brothers they studied shared identical genetic material at one end of the X chromosome, in the region designated as Xq28.

A whole genome study implicated a stretch of DNA on chromosome 7 in the 7q36 region (Mustanski et al.), and a later study of Chinese homosexual men implicated an allele of the SHH (Sonic Hedgehog) gene there (Wang et al., 2012). SHH contributes to the patterning of organ development, from growth of fingers to organization of the brain, but it is also involved in male-male sexual activity, at least in fruit flies. Female sexual orientation, by contrast, does not appear to be linked to 7q36 (S. Hu et al., 1995; Ngun & Vilain, 2014).

(a) The X chromosome, showing the Xq28 region (b) Chromosome 7 indicating region 7q36 and the relative location of the SHH gene

5. What is the evidence for a biological basis for homosexuality?

Evidence that homosexuality is influenced by genes presents a Darwinian contradiction; how could homosexuality survive when its genes are unlikely to be passed on by the homosexual individual?

Italian researchers have offered an intriguing proposal; the birth rate is higher in women on the mother’s side of the family of male homosexuals, so they conclude that genes responsible for homosexuality also increase the women’s birth rate—compensating for the homosexual’s lack of productivity (Camperio Ciani, Corna, & Capiluppi, 2004; Iemmola & Camperio Ciani, 2009).

A later analysis indicated that this effect is best explained by two genes, at least one of which is on the X chromosome; the researchers also suggested that the genes increase attraction to men, in both men and women (Camperio Ciani, Cermelli, & Zanzotto, 2008).

6. Hormonal influence of sextual orientation

Presumably, prenatal androgenization is responsible for this increased incidence of a masculinized sexual orientation. If the differences seen in sexual orientation are caused by effects of prenatal androgens on brain development, then we could reasonably conclude that exposure of the male brain to prenatal androgens plays a role in establishing a sexual orientation toward females, too. That is, sexual orientation in men is probably affected by masculinizing (and defeminizing) effects of androgens on the brain

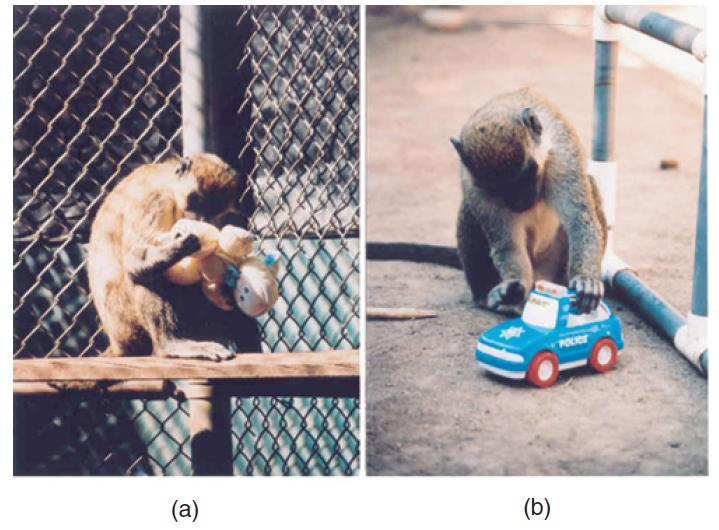

Sex-Typical Toy Choices

- Infant vervet monkeys show sex-typical toy choices: (a) A female playing with a doll. (b) A male playing with a toy car.

Children typically show sex differences in behaviors such as toy preferences (Alexander, 2003).

Boys generally prefer toys that can be used actively, especially those that move or can be propelled by the child. Girls generally prefer toys that provide the opportunity for nurturance. Of course, it is an undeniable fact that both caregivers and peers encourage “sex-typical” toy choices. However, evidence suggests that biology may play a role in the nature of these choices. For example, even at one day of age, baby boys prefer to watch a moving mobile and baby girls prefer to look at a female face (Connellan et al., 2000). Alexander and Hines (2002) found that young vervet monkeys showed the same sexually dimorphic preferences in choice of toys that children do: Males chose to play with a car and a ball, whereas females preferred to play with a doll and a pot

Pasterski et al. (2005) found that girls with CAH (congenital adrenal hyperplasia) were more likely to choose male toys than were their non-CAH sisters or female cousins. The girls’ parents reported that they made a special effort to encourage their CAH daughters to play with “girls’ toys” but that this encouragement appeared not to succeed. Thus, the girls’ tendencies to make male toy choices did not seem to be a result of parental pressure.

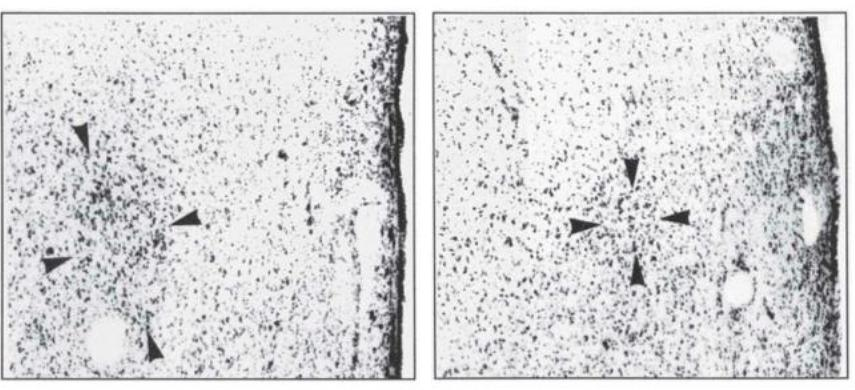

7. Which brain structures are different in homosexual males?

- INAH 3 in a heterosexual man (left) and a homosexual (right)

third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH3)

There is a landmark study on 1991 with the name ‘A difference in hypothalamic structure between heterosexual and homosexual men’ by the one of the all time greatest neuroanatomists Simon LeVay. The nucleus was half the size on homosexual men than on the heterosexual ones. On average gay men had a similar sized nucleus with women. This finding had a huge impact, it proved that there exists a gay brain and made LeVay very famous.

Of course this causes some questions. First of all how much was the variability of the sample. Fair amount. It wasn’t all that reliable but on the average it was about half the size. Also, where did LeVay get the brains from? He took them mostly from men that had died of HIV. Moreover, maybe the nucleus was smaller post-mortem because of its atrophy through the way of living. This is still not concluded but this study has been replicated so there is more elaboration on this.

四、Parental Behavior

- A mother mouse nurses her young pups.

In most mammalian species, reproductive behavior takes place after the offspring are born as well as at the time they are conceived. This section examines the role of hormones in the initiation and maintenance of maternal behavior and the role of the neural circuits that are responsible for their expression.

Most of the research has involved rodents; less is known about the neural and endocrine bases of maternal behavior in primates.

Hormonal Control of Maternal Behavior

As we saw earlier, most sexually dimorphic behaviors are controlled by the organizational and activational effects of sex hormones.

Maternal behavior is somewhat different in this respect.

First, there is no evidence that organizational effects of hormones play a role; as we will see, under the proper conditions even males will take care of infants. (Obviously, males cannot provide infants with milk.)

Second, although maternal behavior is affected by hormones, it is not controlled by them.

Most virgin female rats will begin to retrieve and care for young pups after having infants placed with them for several days (Wiesner and Sheard, 1933). And once the rats are sensitized, they will thereafter take care of pups as soon as they encounter them; sensitization lasts for a lifetime.

Although pregnant female rats will not immediately care for foster pups that are given to them during pregnancy, they will do so as soon as their own pups are born. The hormones that influence a female rodent’s responsiveness to her offspring are the ones that are present shortly before parturition.

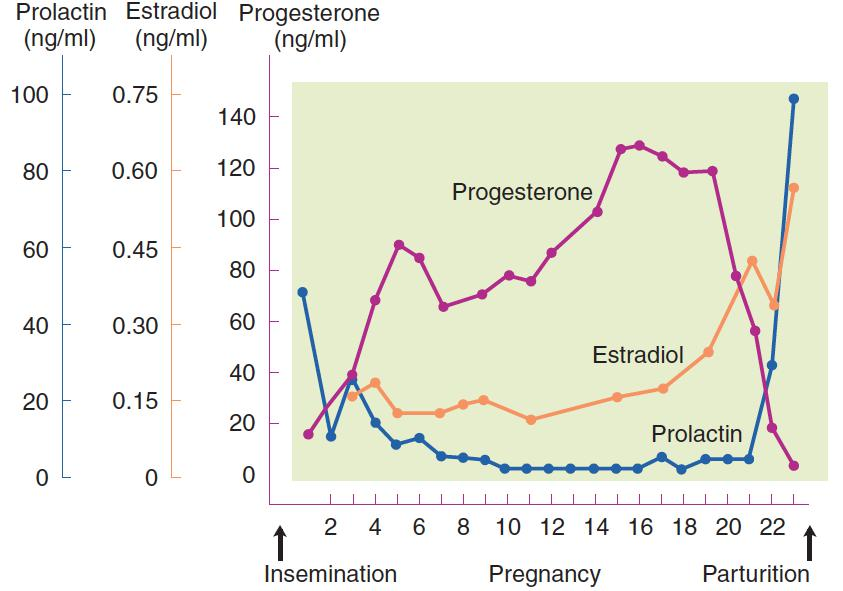

1. Hormones in Pregnant Rats

- The graph shows blood levels of progesterone, estradiol, and prolactin in pregnant rats

This figure shows the levels of the three hormones that have been implicated in maternal behavior: progesterone(黄体酮), estradiol(雌二醇 ), and prolactin(催乳素). Note that just before parturition the level of estradiol begins rising, then the level of progesterone falls dramatically, followed by a sharp increase in prolactin, the hormone produced by the anterior pituitary gland that is responsible for milk production

As we saw earlier, pair bonding involves vasopressin and oxytocin. In at least some species, oxytocin also appears to be involved in formation of a bond between mother and offspring

In rats, the administration of oxytocin facilitates the establishment of maternal behavior (Insel, 1997).

Van Leengoed, Kerker, and Swanson (1987) injected an oxytocin antagonist into the cerebral ventricles of rats as soon as they began giving birth. The experimenters removed the pups from the cage as soon as they were born. When the pups were given back to the mothers forty minutes later, their mothers ignored them. Control rats given a placebo began caring for their pups as soon as the pups were returned to them

Neural Control of Maternal Behavior

The medial preoptic area (MPA), the region of the forebrain that plays the most critical role in male sexual behavior, appears to play a similar role in maternal behavior

Numan (1974) found that lesions of the MPA disrupted both nest building and pup care. The mothers simply ignored their offspring. However, female sexual behavior was unaffected by these lesions

Del Cerro et al. (1995) found that the metabolic activity of the MPA, measured by 2-DG autoradiography, increased immediately after parturition. They also found that virgin females whose maternal behavior had been sensitized by exposure to pups, showed increased activity in the MPA. Thus, stimuli that facilitate pup care activate the MPA.

Numan and Numan (1997) found that neurons of the MPA that are activated by the performance of maternal behavior send their axons to the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Cutting the connections of the MPA with the brain stem abolishes maternal behavior (Numan and Smith, 1984).

An fMRI study with rats (yes, they really put their little heads in a special fMRI scanner) found that regions of the brain that are involved in reinforcement are activated when the mothers are presented with their pups (Ferris et al., 2005). The same regions are activated by artificial reinforcers such as cocaine. However, cocaine activates this region only in virgin females; lactating females actually showed a reduction when they received injections of the drug. To a lactating female, the presence of pups becomes extremely reinforcing, and the potency of other stimuli, which might distract her from providing maternal care, appears to become weaker. Perhaps, say the authors, oxytocin plays a role in this phenomenon

An fMRI study—this time with humans—found that when mothers looked at pictures of their infants, brain regions involved in reinforcement and those that contain receptors for oxytocin and vasopressin showed increased activity. Regions involved with negative emotions, such as the amygdala, showed decreased activity (Bartels and Zeki, 2004). We already know that mothers (and fathers too, for that matter) form intense bonds with their infants, so it should not come as a surprise that regions involved with reinforcement should be activated by the sight of their faces

Neural Control of Paternal Behavior

Newborn infants of most species of mammals are cared for by their mother, and it is, of course, their mother that feeds them. However, males of a few species of rodents share the task of infant care with the mothers, and the brains of these nurturing fathers show some interesting differences compared with those of nonpaternal fathers of other species

Kirkpatrick, Kim, and Insel (1994) found that when male prairie voles were exposed to a pup, neurons in the MPA were activated. In addition, lesions of the MPA produced severe deficits in paternal behavior of male rats and another species of monogamous voles (Rosenblatt, Hazelwood, and Poole, 1996; Sturgis and Bridges, 1997; Lee and Brown, 2007). Thus, the MPA appears to play a similar role in the parental behavior of both males and females.

Little is known about the brain mechanisms involved in human paternal behavior, but evidence suggests that both prolactin and oxytocin facilitate a father’s role in infant care.

Fleming et al. (2002) found that fathers with higher blood levels of prolactin reported stronger feelings of sympathy and activation when they heard the cries of infants. Gordon et al. (2010) found that higher levels of prolactin were associated with more exploratory toy-manipulating play behavior with their infants, and that higher levels of oxytocin were associated with synchronous, coordinated emotional behavior between father and infant