L18 Cell Division- Mitosis

一、Overview of the cell division

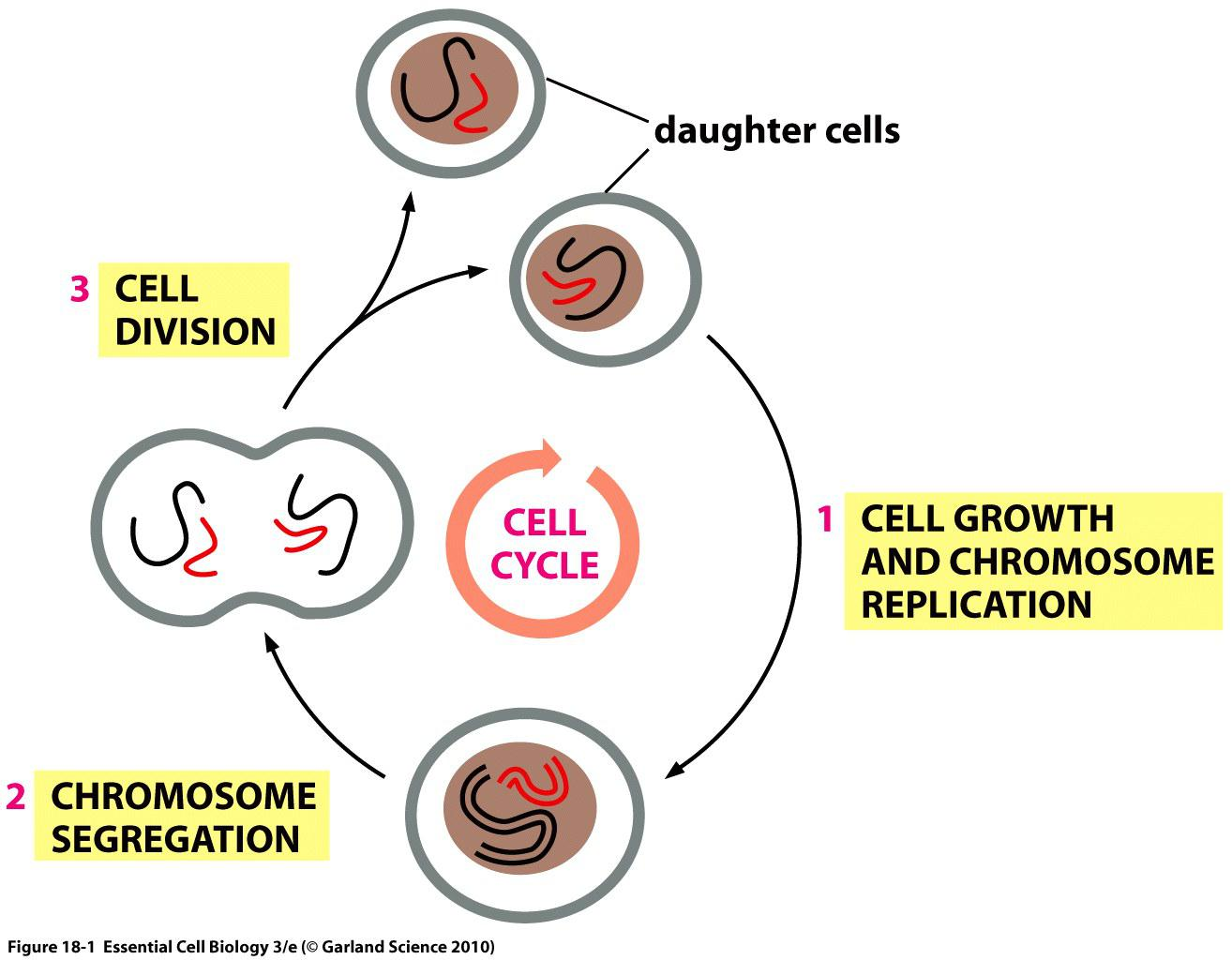

Cells reproduce by duplicating their contents and dividing in two.

This cycle of duplication and division, known as the cell cycle, is the essential mechanism by which all living things reproduce.

The details of the cell cycle vary from organism to organism and at different times in an organism’s life.

cell-cycle control system, a complex network of regulatory proteins that triggers the different events of the cycle.

When does a cell decide to divide? (Lecture 19)

How does the cell cycle progress?

- What is the driving force of cell cycle progression?

- DNA duplication and chromosome segregation?

How is cell cycle controlled to ensure faithful DNA duplication and chromosome segregation? (Lecture 19)

- Doubling time

Yeast cell: 1.5-3 hrs

Fertilized xenopus oocytes: 30 min

Mammalian intestine epithelial cells: 12 hrs

Mammalian fibroblasts: 20 hrs

Tobacco BY2 suspension cultured cell: 22 hrs

The major events in cell cycle

There are several basic steps in cell division:

- Cell growth

- Cells often but not always attain certain size to begin division.

- Accumulate enough material to support 2 cells.

- Duplication of chromosomes

- Cells need full and accurate complement of DNA.

- Repair damage and copy DNA.

- Chromosome segregation

- Ensure that both daughter cells receive full set of chromosomes.

- Cytokinesis

- Separating 2 cells.

- Pinching and closing plasma membrane.

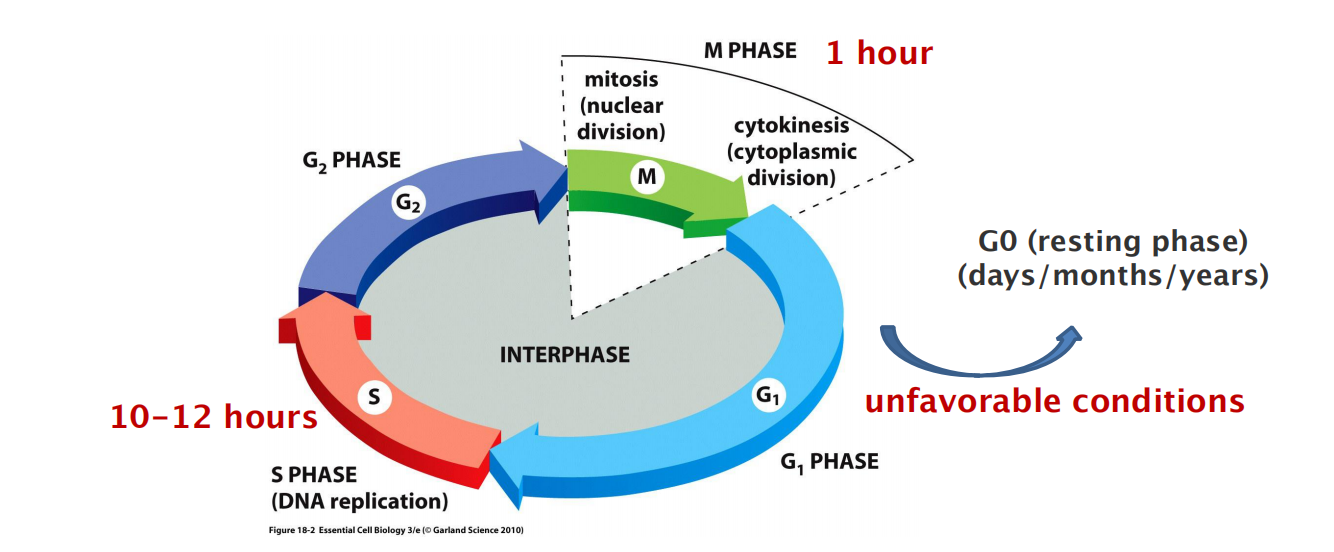

Chromosome duplication occurs during S phase (S for DNA synthesis), which requires 10–12 hours and occupies about half of the cell-cycle time in a typical mammalian cell.

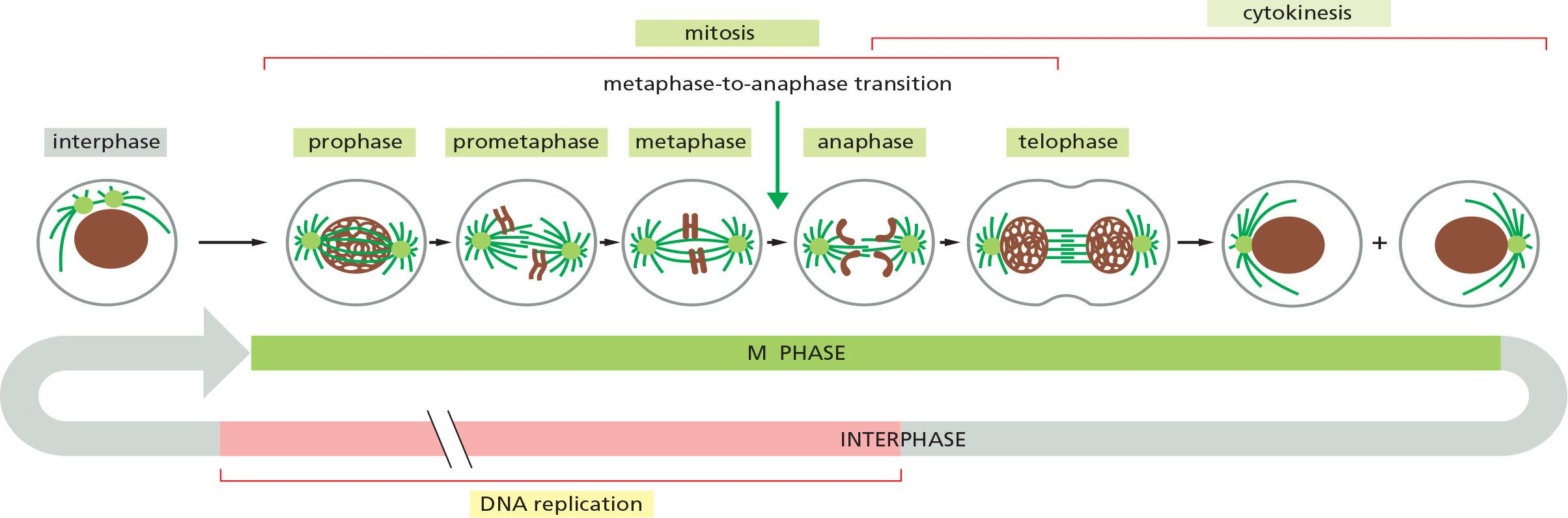

After S phase, chromosome segregation and cell division occur in M phase (M for mitosis), which requires much less time (less than an hour in a mammalian cell). M phase comprises two major events: nuclear division, or mitosis, during which the copied chromosomes are distributed into a pair of daughter nuclei; and cytoplasmic division, or cytokinesis, when the cell itself divides in two

At the end of S phase, the DNA molecules in each pair of duplicated chromosomes are intertwined and held tightly together by specialized protein linkages.

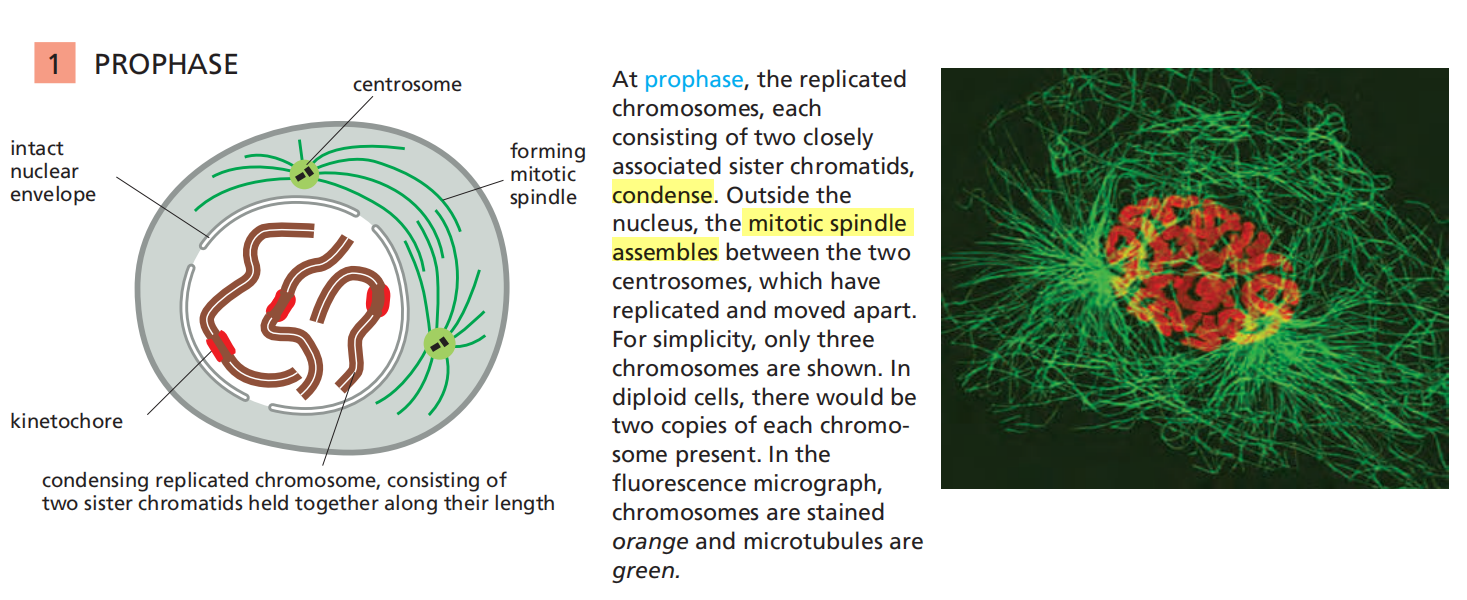

Early in mitosis at a stage called prophase, the two DNA molecules are gradually disentangled and condensed into pairs of rigid, compact rods called sister chromatids, which remain linked by sister-chromatid cohesion

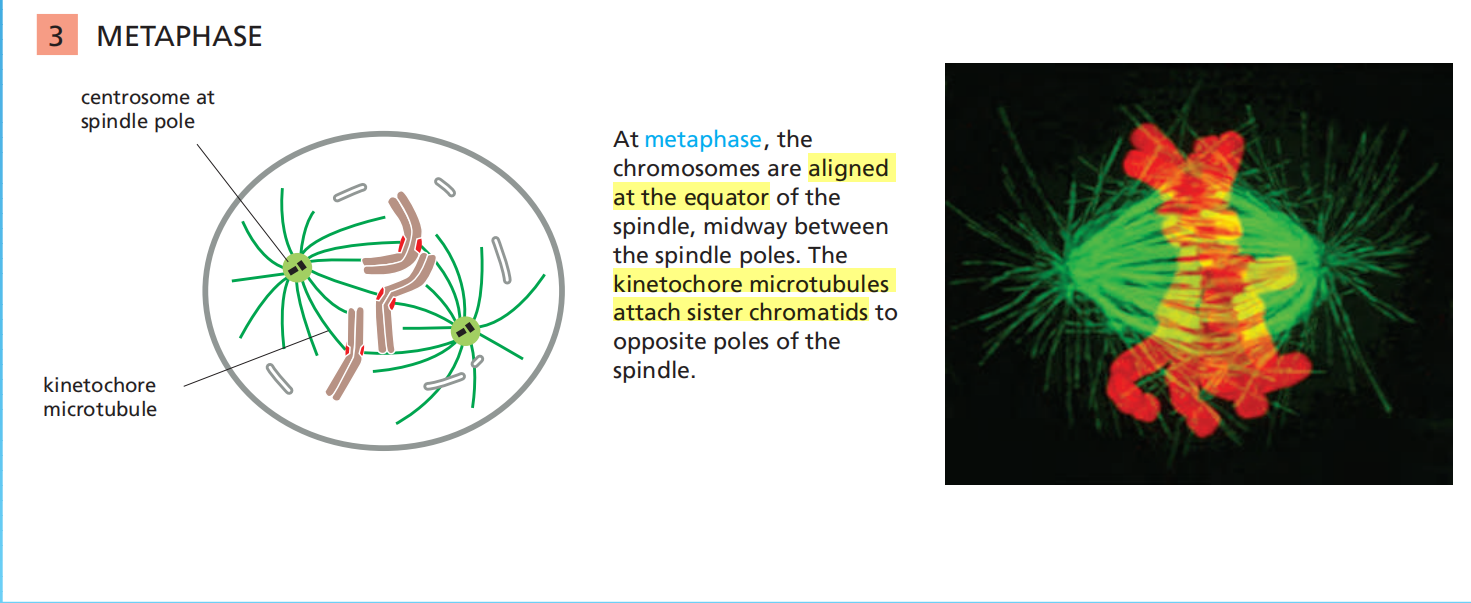

When the nuclear envelope disassembles later in mitosis, the sister-chromatid pairs become attached to the mitotic spindle, a giant bipolar array of microtubules (discussed in Chapter 16). Sister chromatids are attached to opposite poles of the spindle and, eventually, align at the spindle equator in a stage called metaphase.

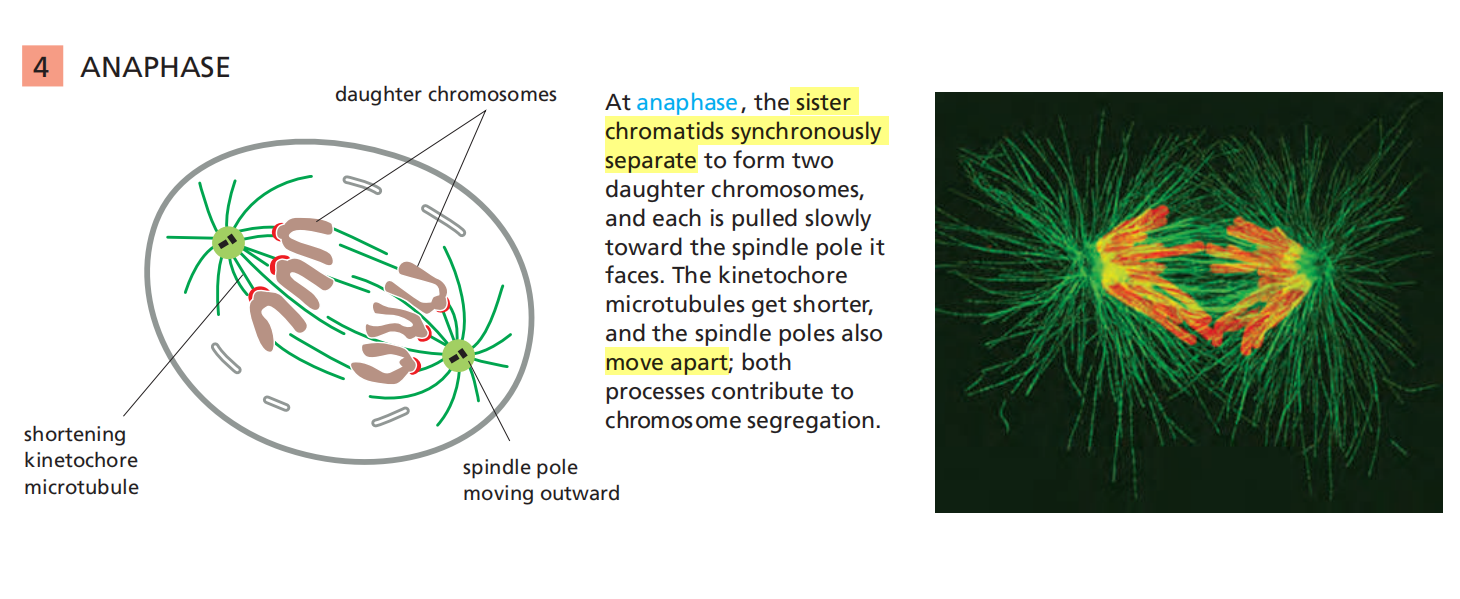

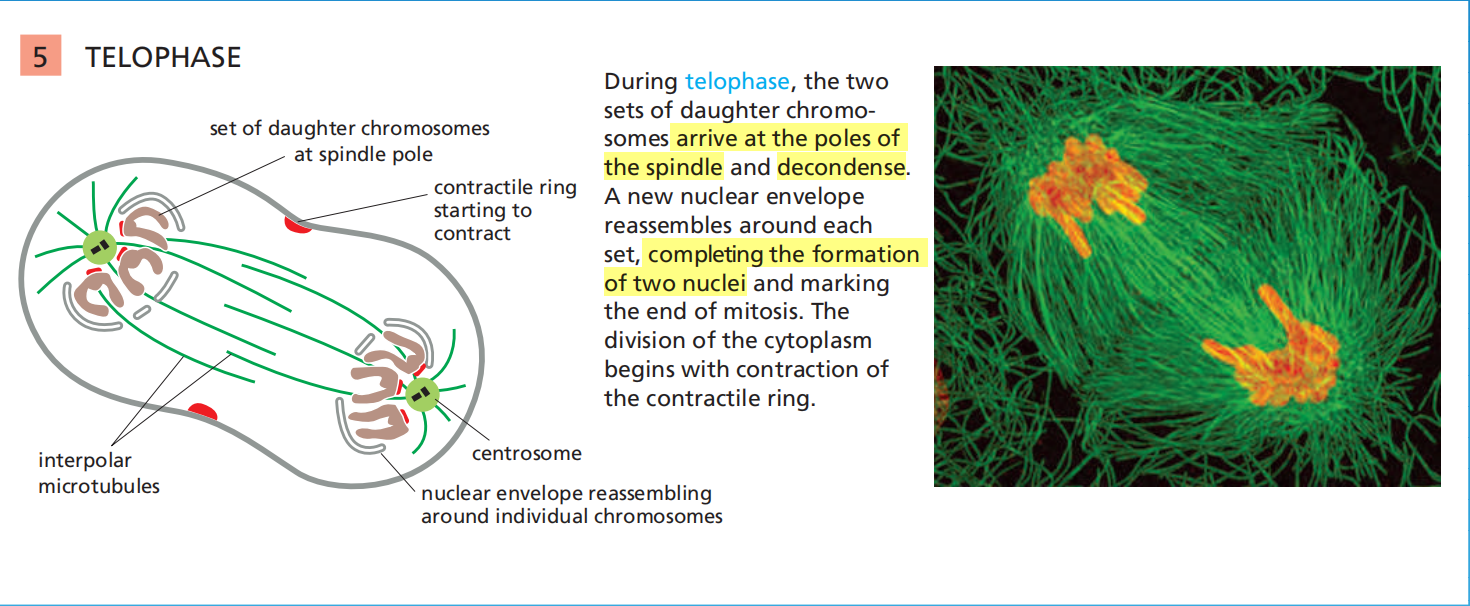

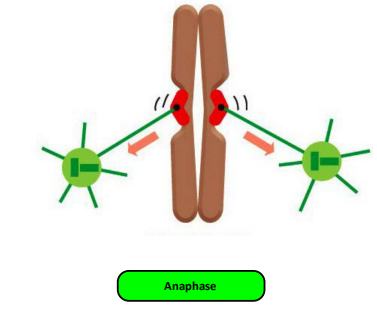

The destruction of sister-chromatid cohesion at the start of anaphase separates the sister chromatids, which are pulled to opposite poles of the spindle. The spindle is then disassembled, and the segregated chromosomes are packaged into separate nuclei at telophase

- Cytokinesis then cleaves the cell in two, so that each daughter cell inherits one of the two nuclei

The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle Usually Consists of Four Phases

Partly to allow time for growth, most cell cycles have gap phases—a G

1phase between M phase and S phase and a G2phase between S phase and mitosis.

- G1, S, G2, and M.

- G1, S, and G2 together are called interphase

Cell growth occurs throughout the cell cycle, except during mitosis.

The two gap phases are more than simple time delays to allow cell growth. They also provide time for the cell to monitor the internal and external environment to ensure that conditions are suitable and preparations are complete before the cell commits itself to the major upheavals of S phase and mitosis

The G1 phase is especially important in this respect. Its length can vary greatly depending on external conditions and extracellular signals from other cells.

- If extracellular conditions are unfavorable, for example, cells delay progress through G1 and may even enter a specialized resting state known as G

0(G zero), in which they can remain for days, weeks, or even years before resuming proliferation. Indeed, many cells remain permanently in G0until they or the organism dies.If extracellular conditions are favorable and signals to grow and divide are present, cells in early G

1or G0progress through a commitment point near the end of G1known as Start (in yeasts) or the restriction point (in mammalian cells)

Cell-Cycle Control Is Similar in All Eukaryotes

Some features of the cell cycle, including the time required to complete certain events, vary greatly from one cell type to another, even in the same organism

- All eukaryotes appear to use similar machinery and control mechanisms to drive and regulate cell-cycle events

Definitions

- M phase: nuclear division (mitosis) and cell division

- Interphase: time between M phases

- G1/2 phases: gap phases (checking internal state and external environment)

- S phase: synthesis

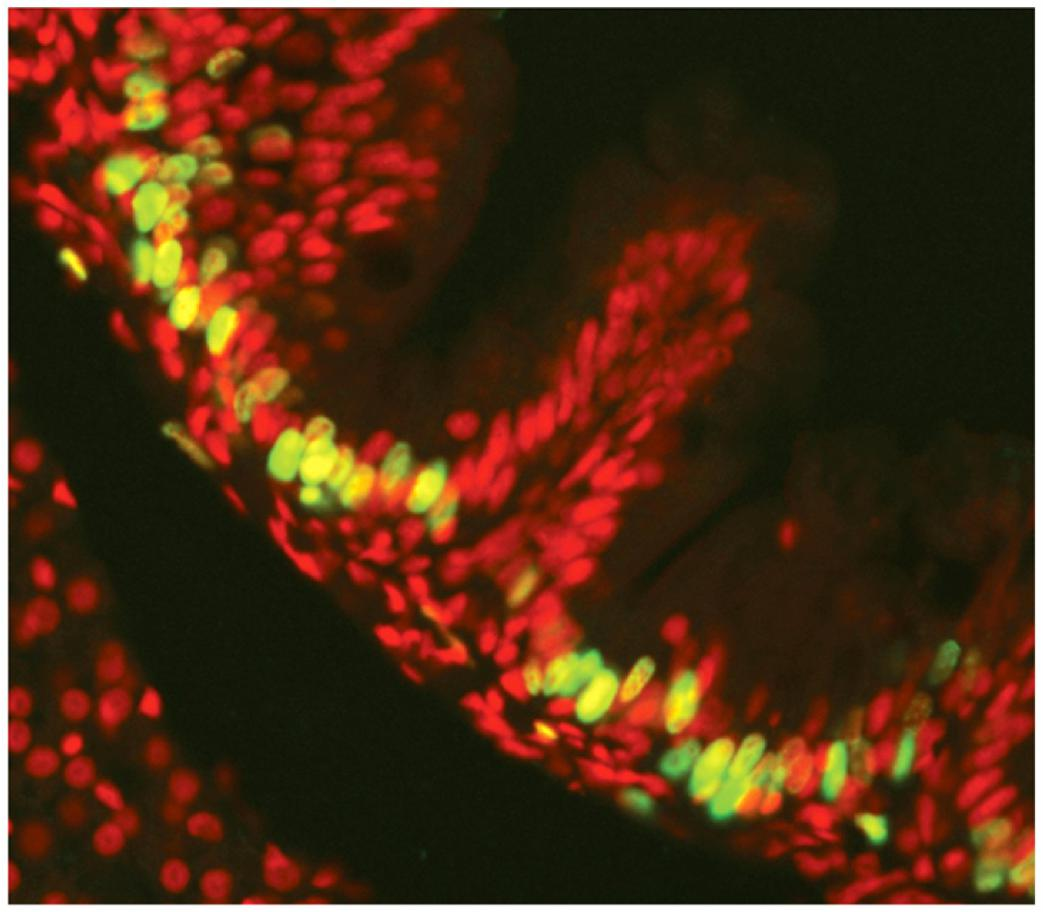

1. Identification and quantification of cells in S-phase: BrdU or EdU incorporation

- BrdU-labeled epithelial cells of the zebrafish gut. The fish was exposed to BrdU, after which the tissue was fixed and prepared for labeling with fluorescent anti-BrdU antibodies (green). All the cells are stained with a red fluorescent dye.

Labeling of the DNA

- Incubation of cells with thymidine (T) analogs like BrdU or EdU to incorporate the substance in the DNA during DNA synthesis (→DNA labeling)

Detection of the incorporated BrdU/EdU

- BrdU: Immunofluorescence (fluorescent anti-BrdU antibodies)

- EdU: Crosslink to fluorescent azide

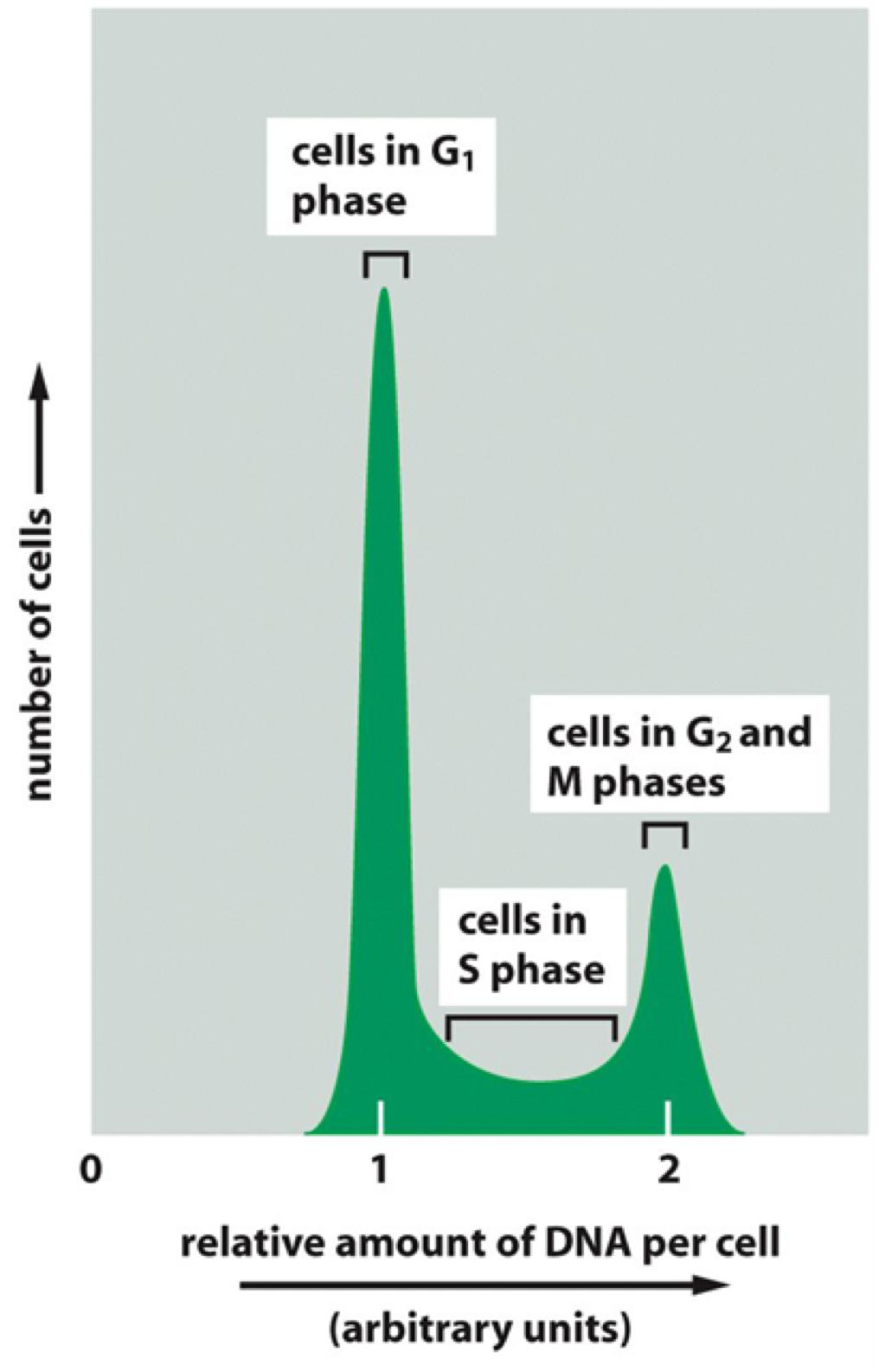

3. Cell cycle-distribution analysis

Flow Cytometry

Cell cycle-distribution analysis using flow cytometry to detect cell cycle phases within a cell population

Labeling of the DNA in the cells: Incubation of cells with fluorescent DNA-binding dyes (Propidium Iodide (PI) (Ex = 535 nm Em = 617 nm, Red fluorescence)

Detection of the labeled DNA by flow cytometry using an “Cell Analyzer”

Amount of DNA corresponds to specific stages in the cell cycle

Light Microscopy

Labeling of the DNA in the cells: Incubation of cells with fluorescent DAPI/Hochest (Ex = UV Em = 461 nm, Blue fluorescence) (fixed or live cell)

Calculation of mitotic index (MI): ratio of mitotic cell numbers to total cell numbers

Morphological changes, durations of each mitotic stage

二、Cell-Cycle Control System

Model organisms to study cell cycle

- Xenopus (frog) oocytes/embryos (biochemistry)

- biochemical dissection of cell-cycle control mechanisms

- Yeasts (genetics)

- simple eukaryotes to identify genes and proteins involved in the cell cycle fission yeast (Shizosaccharomyces pombe) budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

- Drosophila (fly) (genetics)

- genetic analysis of mechanisms underlying control and coordination of cell growth and division

- Mammalian cells (human diseases)

- molecular and microscopic exploration of the complex processes by which our own cells divide

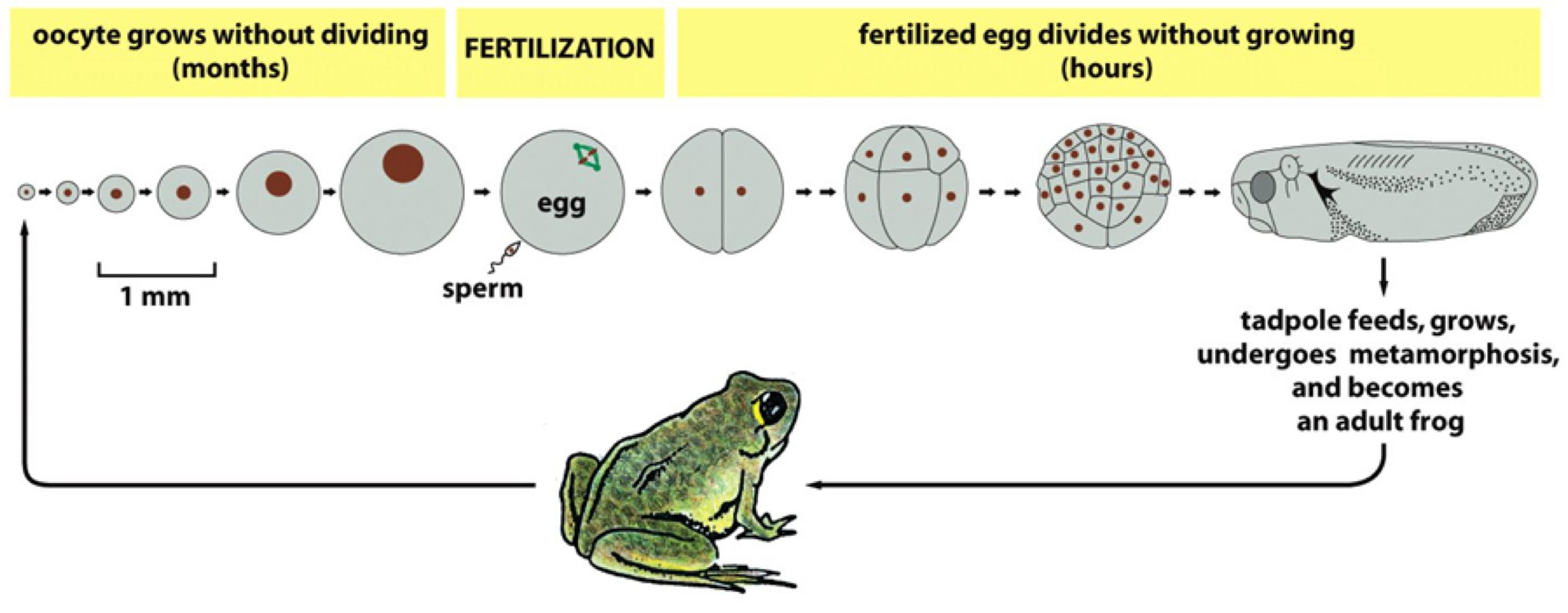

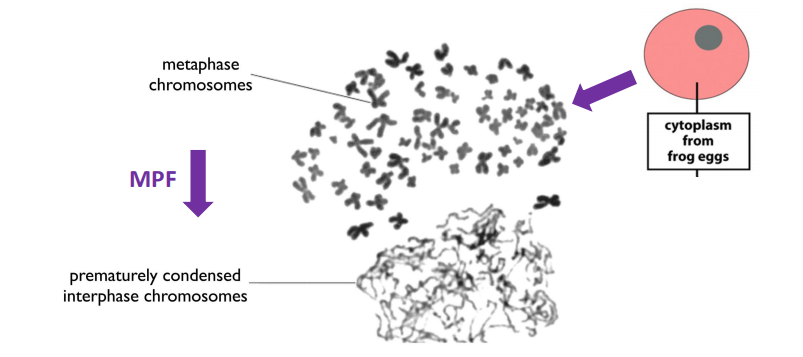

1. Model systems to study the cell cycle: Xenopus oocytes

Fertilized eggs are exceptionally large and divide rapidly (S and M phases, with very short or no G1 or G2 phases)

No new gene transcription in the fertilized egg:

- all of the required mRNAs and proteins are already packed into the very large egg

No cell growth in these early embryonic division cycles (cleavage divisions)

- all cells divide synchronously, growing smaller and smaller with each division

- → Xenopus oocytes have rich source of cell division proteins

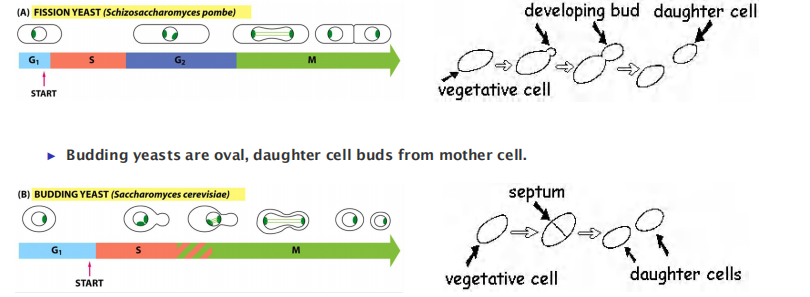

2. Model organisms to study the cell cycle: Yeast

- Fission yeasts are rod, septum divides into two daughter cells.

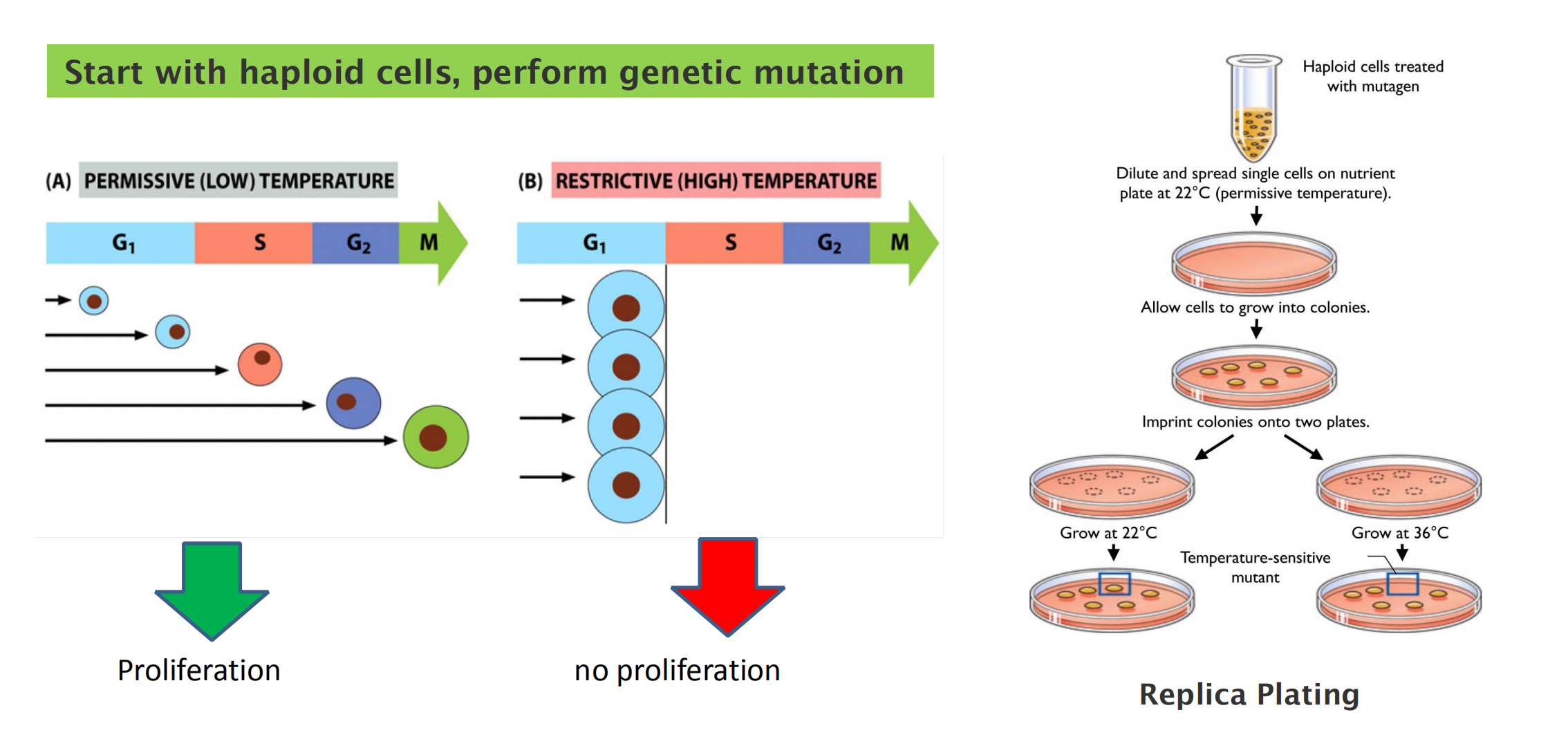

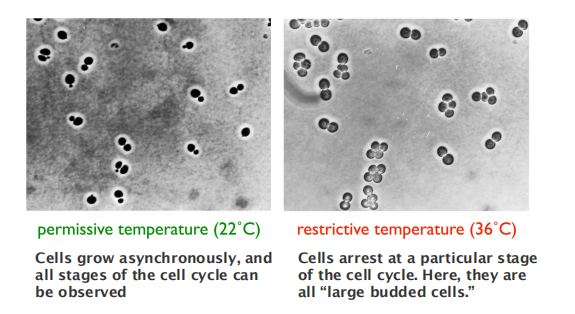

Conditional mutation in yeast cells for cell cycle studies:

Temperature-sensitive mutations in cell cycle control genes cause all cells to arrest at a specific stage.

Cell Cycle Related Regulatory Molecules

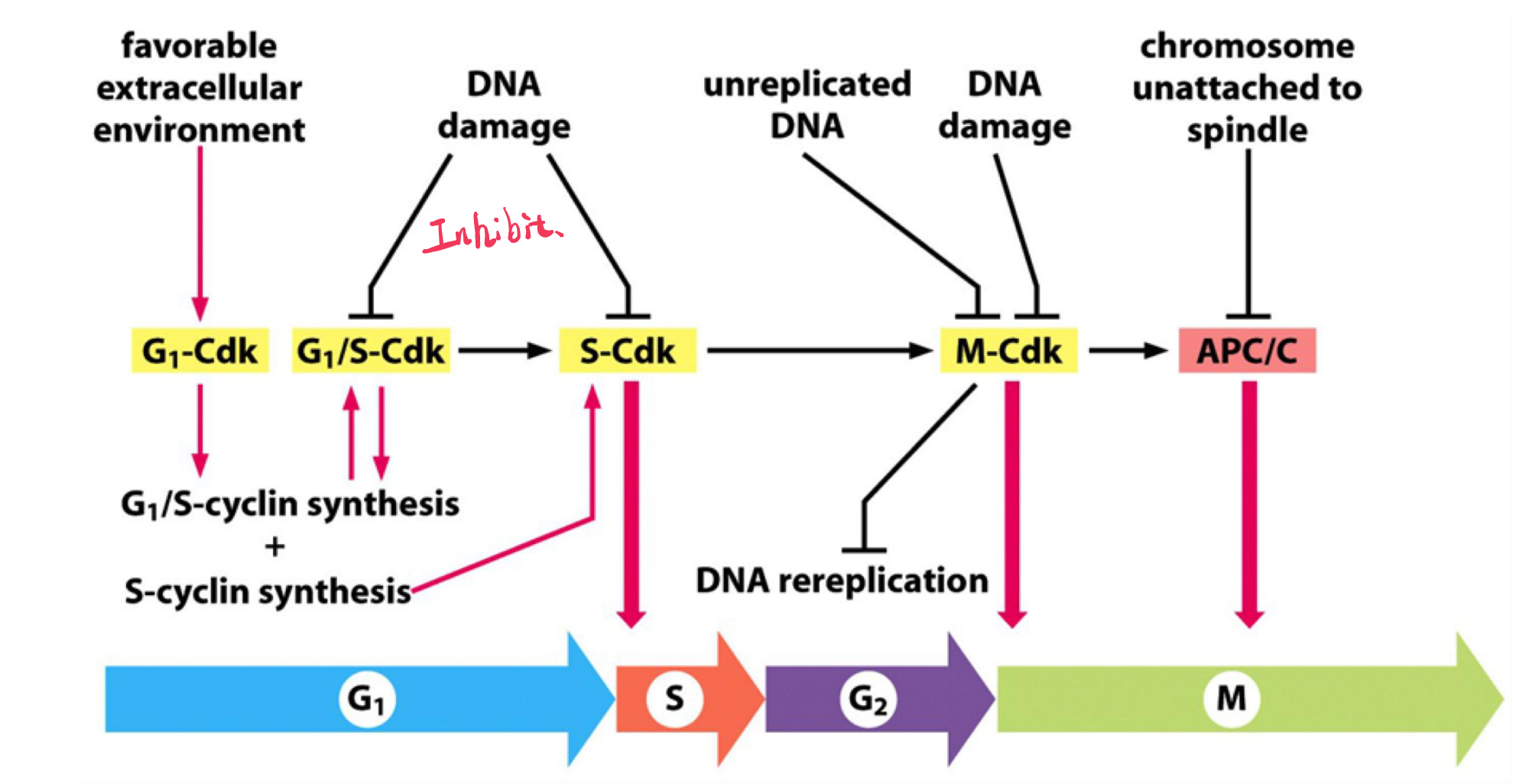

The Cell-Cycle Control System Triggers the Major Events of the Cell Cycle

- The cell-cycle control system operates much like a timer that triggers the events of the cell cycle in a set sequence

- In most cells, however, the control system does respond to information received back from the processes it controls

The cell-cycle control system is based on a connected series of biochemical switches, each of which initiates a specific cell-cycle event.

- First, the switches are generally binary (on/off) and launch events in a complete, irreversible fashion. It would clearly be disastrous

- Second, the cell-cycle control system is remarkably robust and reliable, partly because backup mechanisms and other features allow the system to operate effectively under a variety of conditions and even if some components fail

- Finally, the control system is highly adaptable and can be modified to suit specific cell types or to respond to specific intracellular or extracellular signals.

Cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases (Cdks) drive cell cycle events

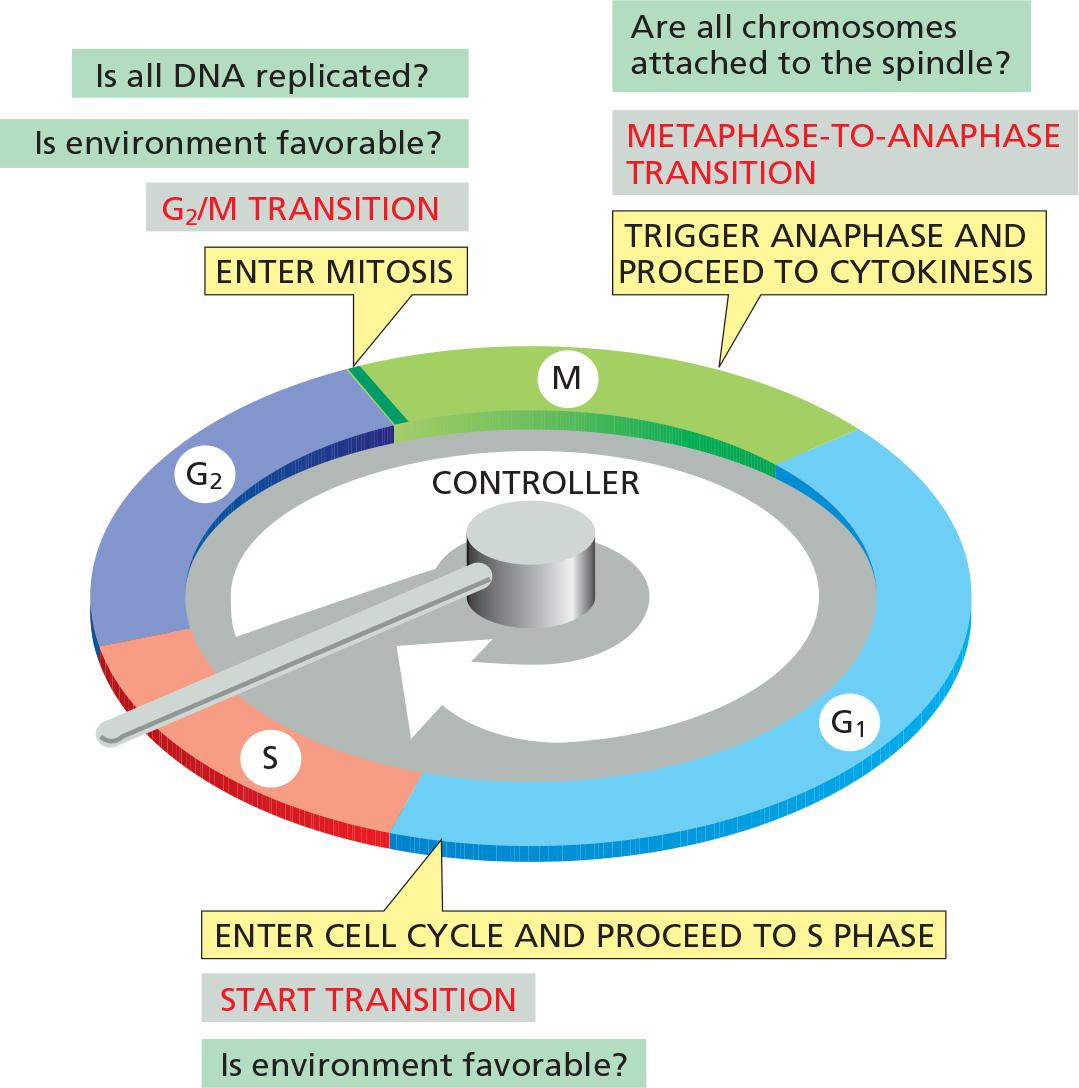

In most eukaryotic cells, the cell-cycle control system governs cell-cycle progression at three major regulatory transitions

- The first is Start (or the restriction point) in late G1, where the cell commits to cell-cycle entry and chromosome duplication

- The second is the G2/M transition, where the control system triggers the early mitotic events that lead to chromosome alignment on the mitotic spindle in metaphase.

- The third is the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, where the control system stimulates sister-chromatid separation, leading to the completion of mitosis and cytokinesis.

The control system blocks progression through each of these transitions if it detects problems inside or outside the cell. If the control system senses problems in the completion of DNA replication, for example, it will hold the cell at the G2/M transition until those problems are solved. Similarly, if extracellular conditions are not appropriate for cell proliferation, the control system blocks progression through Start, thereby preventing cell division until conditions become favorable

- The three check points

- The driving force of cell cycle progression is evolutionarily conserved.

1. Cdks

The Cell-Cycle Control System Depends on Cyclically Activated Cyclin-Dependent Protein Kinases (Cdks)

- Central components of the cell-cycle control system are members of a family of protein kinases known as cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks)

An increase in Cdk activity at the G2/M transition, for example, increases the phosphorylation of proteins that control chromosome condensation, nuclear-envelope breakdown, spindle assembly, and other events that occur in early mitosis.

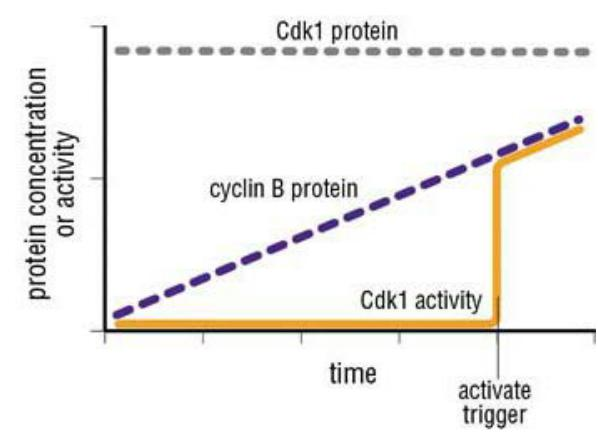

Cyclical changes in Cdk activity are controlled by a complex array of enzymes and other proteins. The most important of these Cdk regulators are proteins known as cyclins

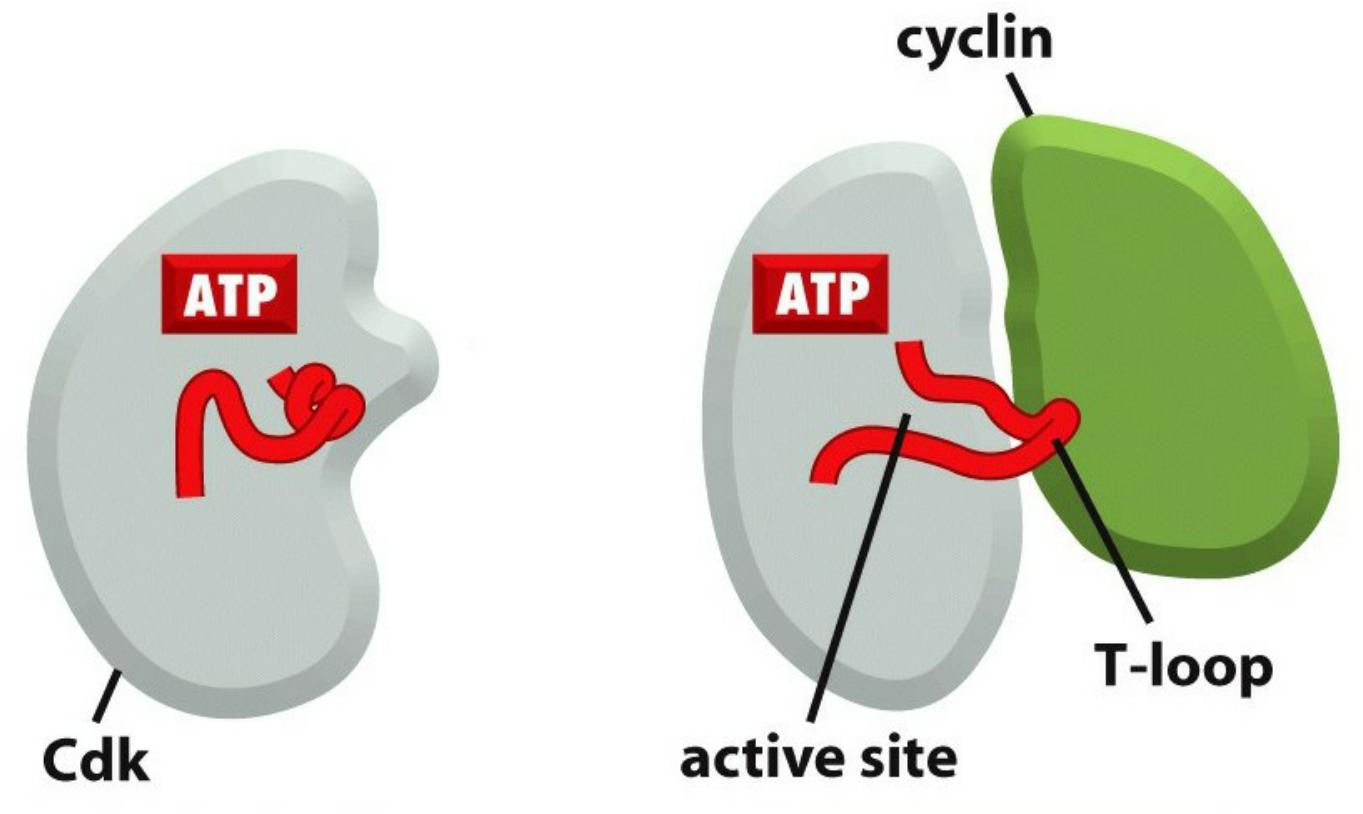

- Cdks, as their name implies, are dependent on cyclins for their activity: unless they are bound tightly to a cyclin, they have no protein kinase activity (Figure 17–10).

Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks): Ser/Thr kinases

- Protein kinases, phosphorylate a subset of substrates to control cell cycle progression at specific checkpoints.

- Level of Cdks is constant throughout the cell cycle

- Cdk1: Cdc28 in budding yeast, cdc2 in fission yeast, Cdk1 in vertebrate

- Cdk2, Cdk4, Cdk6

2. Cyclins

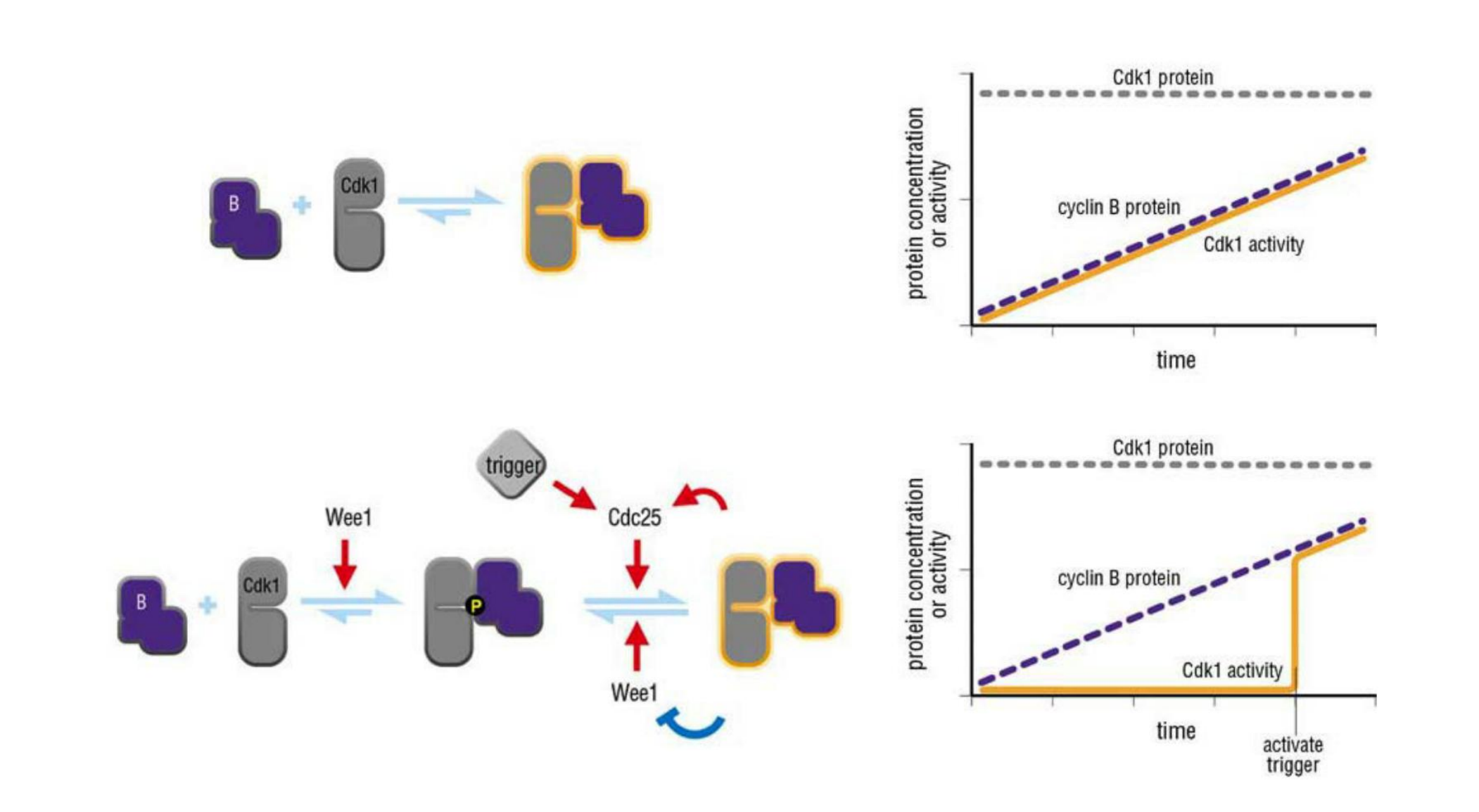

The levels of the Cdk proteins, by contrast, are constant. Cyclical changes in cyclin protein levels result in the cyclic assembly and activation of cyclin–Cdk complexes at specific stages of the cell cycle.

- Cyclin named so because they undergo a cycle of synthesis & degradation during each cell cycle

- Cyclin protein synthesis and degradation drive the cell cycle

Cyclin-Cdk Complex

Cyclin-Cdk complex:

- When cyclin forms a complex with Cdk, the protein kinase is activated to trigger specific cell-cycle events.

- Without cyclin, Cdk is inactive.

- Cyclin decides cdk substrates specificity and activates Cdk.

- Different cyclins oscillate in cell cycle and bind to or control the activity of different Cdks.

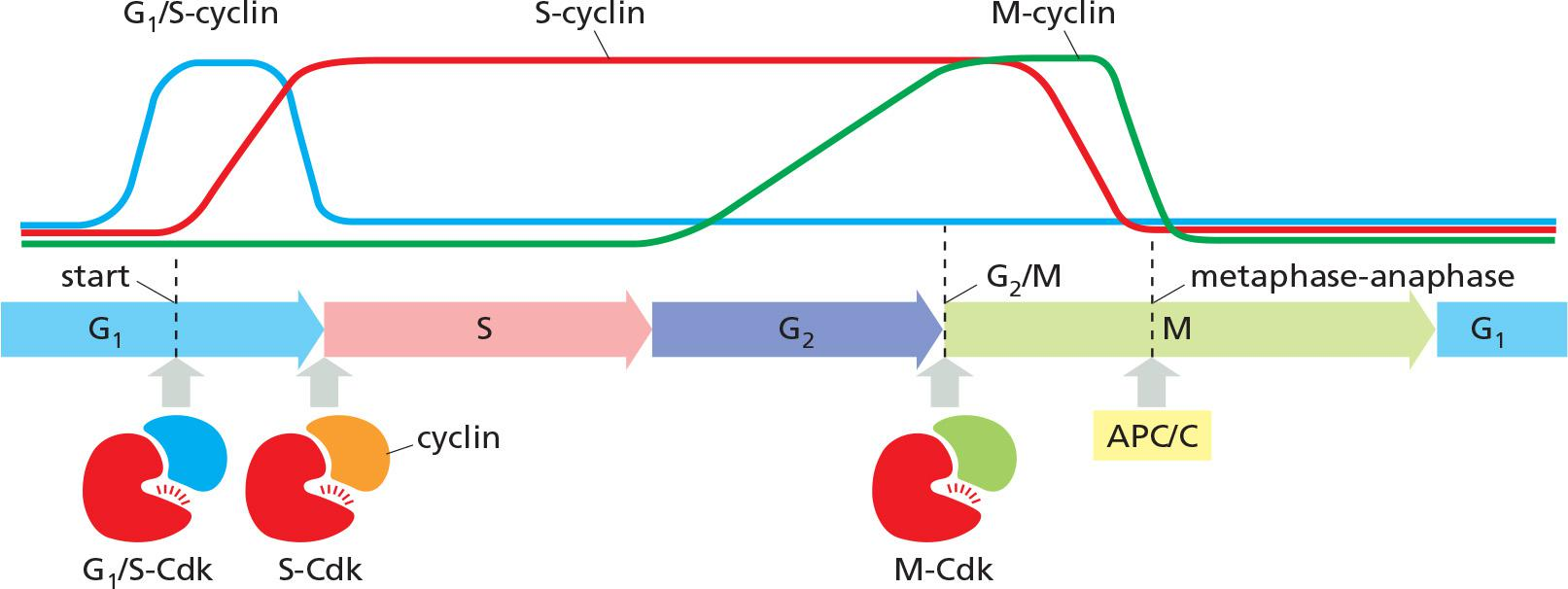

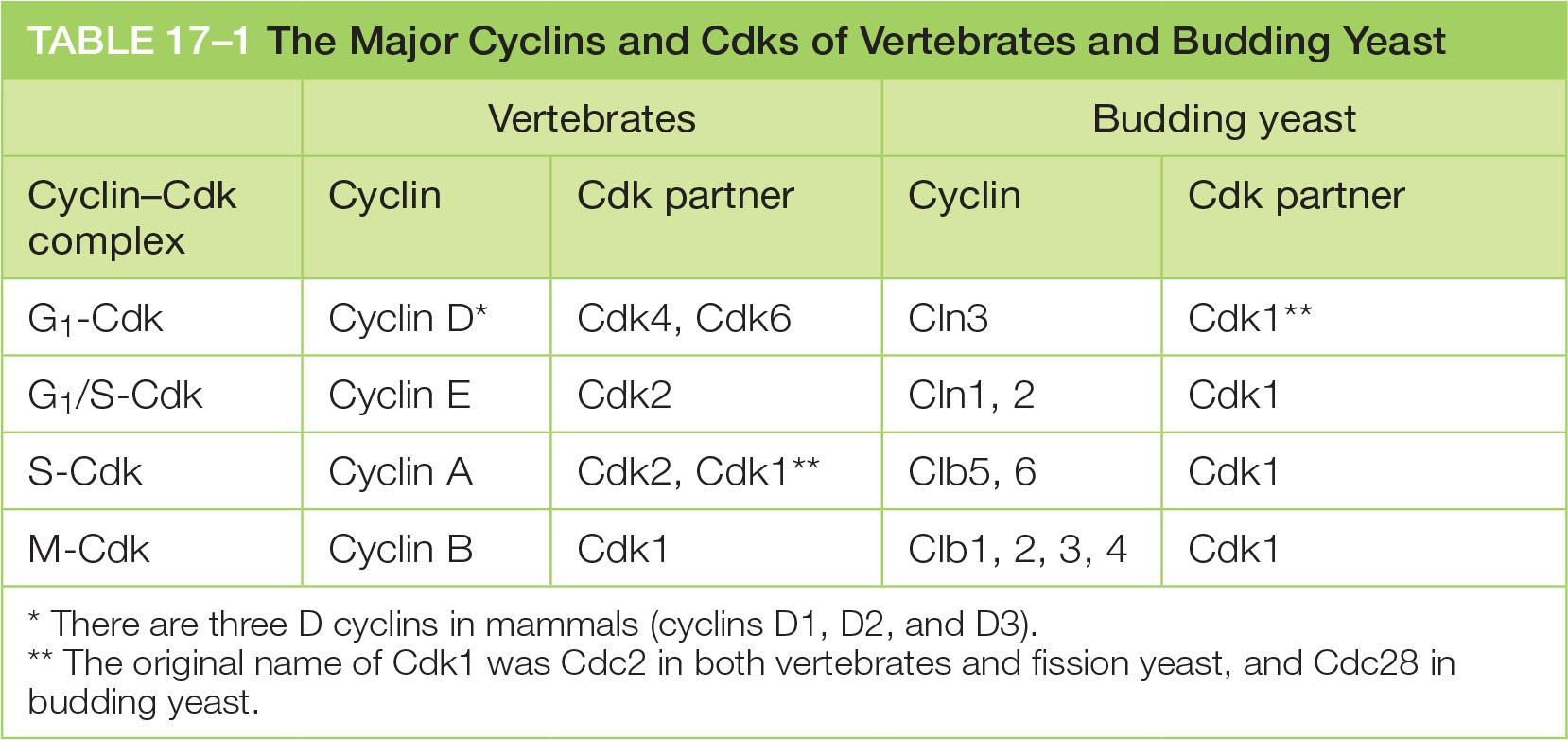

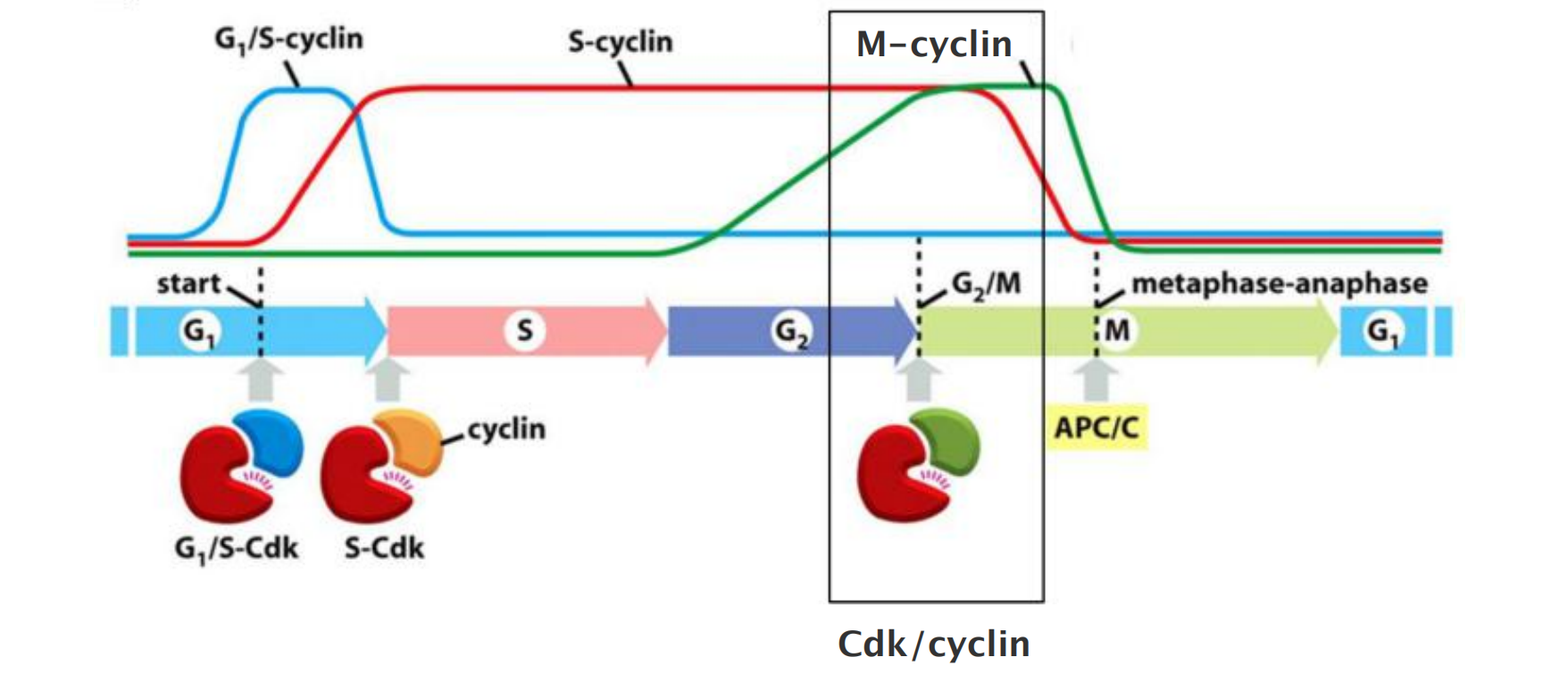

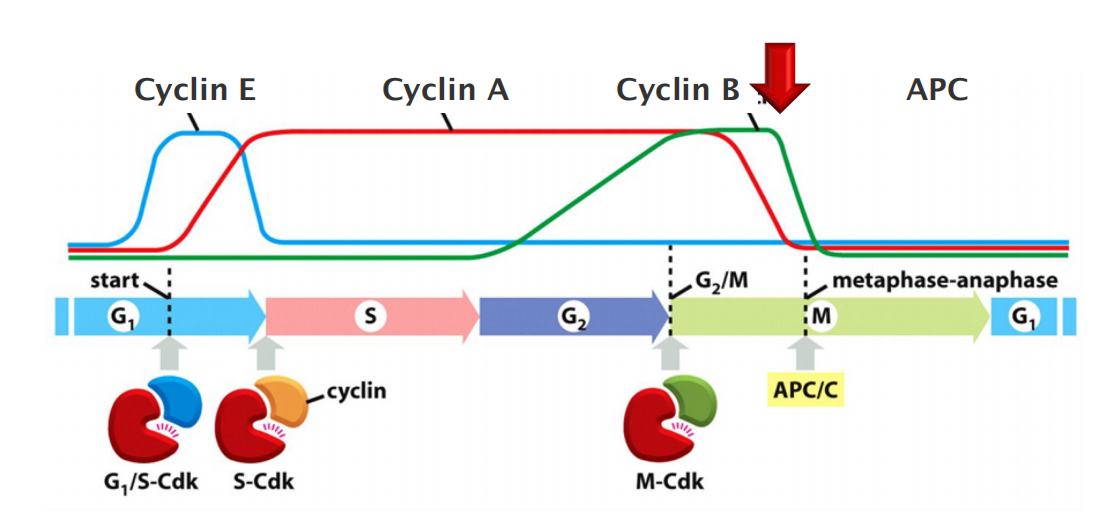

There are four classes of cyclins, each defined by the stage of the cell cycle atwhich they bind Cdks and function. All eukaryotic cells require three of these classes

- G1/S-cyclins activate Cdks in late G1 and thereby help trigger progression through Start, resulting in a commitment to cell-cycle entry. Their levels fall in S phase.

- S-cyclins bind Cdks soon after progression through Start and help stimulate chromosome duplication. S-cyclin levels remain elevated until mitosis, and these cyclins also contribute to the control of some early mitotic events.

- M-cyclins activate Cdks that stimulate entry into mitosis at the G2/M transition. M-cyclin levels fall in mid-mitosis

In most cells, a fourth class of cyclins, the G1-cyclins, helps govern the activities of the G1/S-cyclins, which control progression through Start in late G1.

- In yeast cells, a single Cdk protein binds all classes of cyclins and triggers different cell-cycle events by changing cyclin partners at different stages of the cycle.

- In vertebrate cells, by contrast, there are four Cdks. Two interact with G1-cyclins, one with G1/Sand S-cyclins, and one with S- and M-cyclins

the cyclin protein does not simply activate its Cdk partner but also directs it to specific target proteins. As a result, each cyclin–Cdk complex phosphorylates a different set of substrate proteins.

- The same cyclin–Cdk complex can also induce different effects at different times in the cycle, probably because the accessibility of some Cdk substrates changes during the cell cycle.

Waves of cyclin expression and degradation

Waves of cyclin expression and degradation mediate ordered progression of cell cycle

- G1/S-cyclins activate Cdks in late G1 trigger progression through the Start transition.

- →Commitment to cell-cycle entry.

- S-cyclins activate Cdks soon after Start and trigger DNA replication and early mitotic events.

- M-cyclins activate Cdks to trigger entry into mitosis at the G2/M transition.

- M-cyclin degradation by APC/C (ubiquitin ligase), initiates the metaphase-to-anaphase transition.

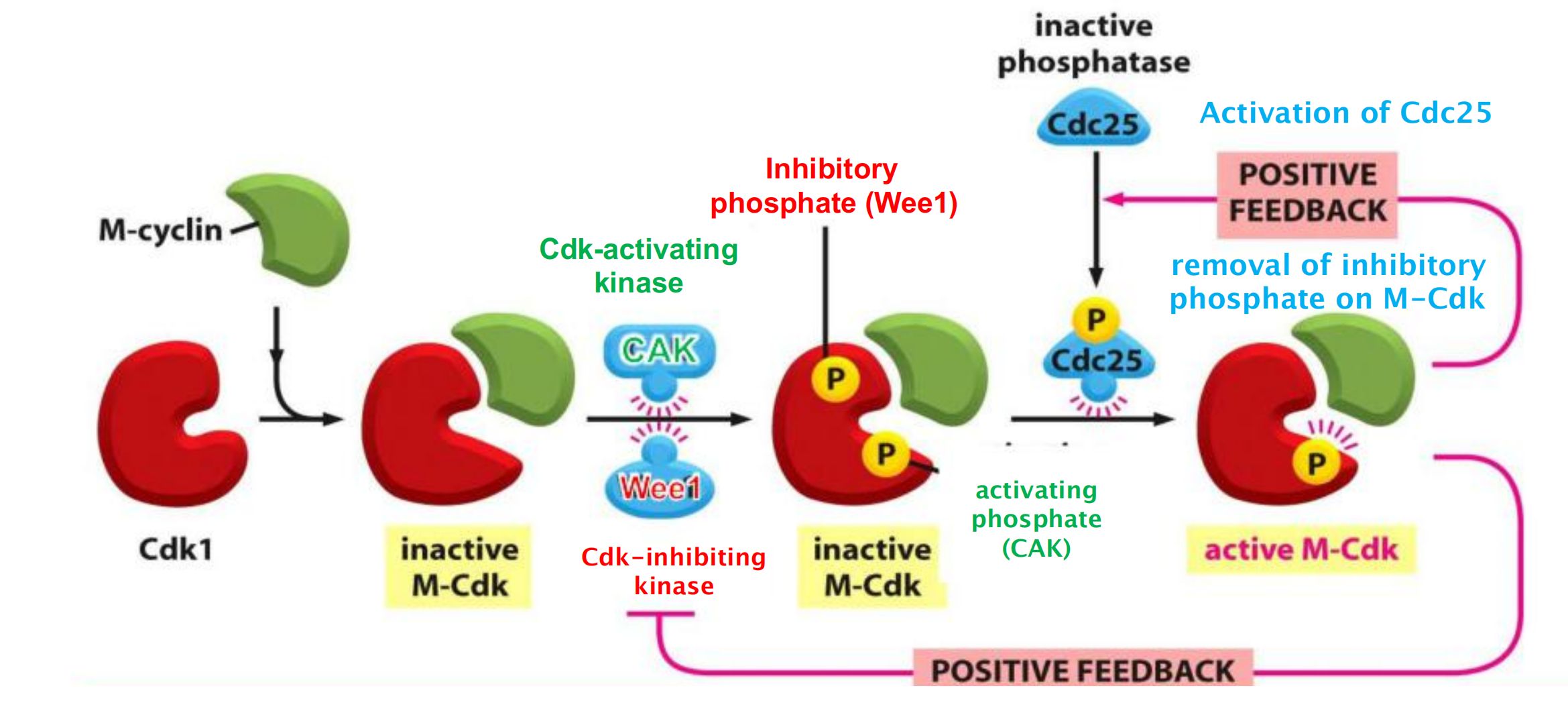

Cdk Activation

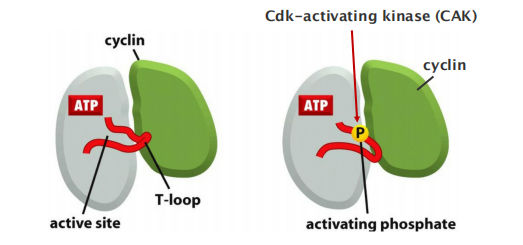

Association with cyclin opens ATP-binding pocket of CDKs.

CDK-activating kinases phosphorylate CDKs to open substrate binding site.

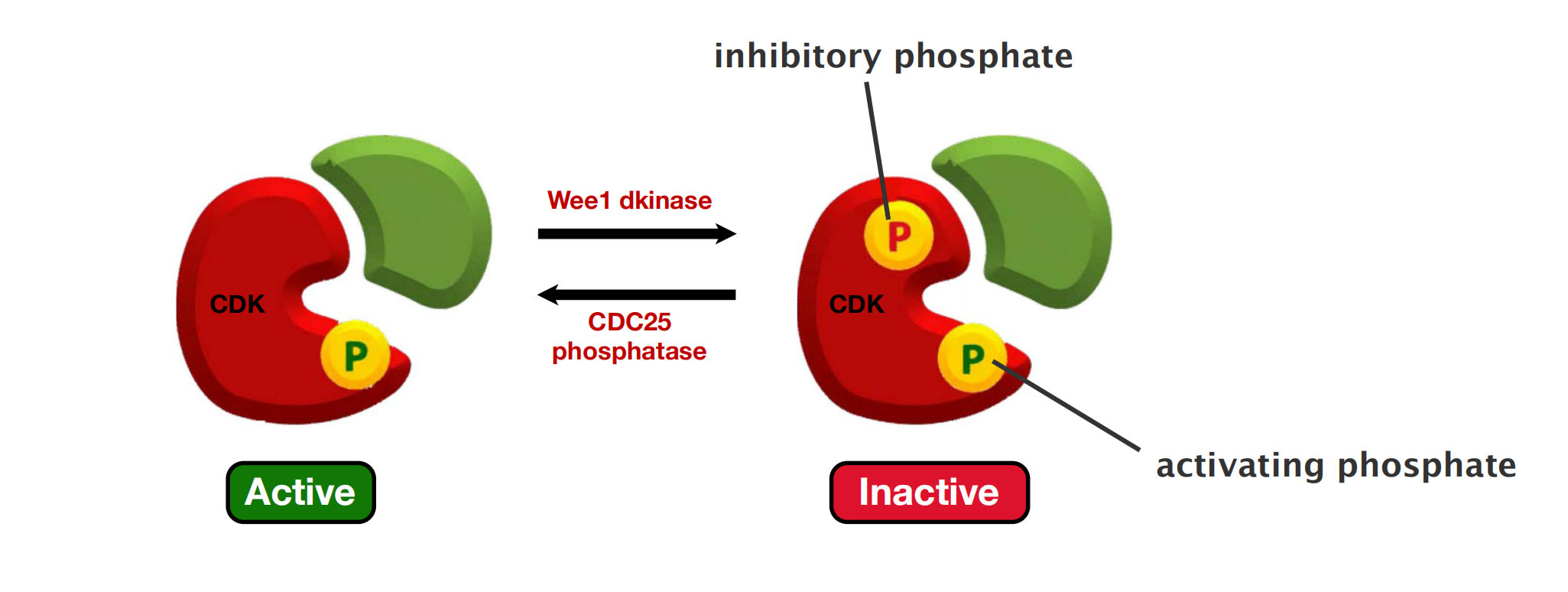

Inhibitory phosphate inactivates cyclin-CDK complexes site

- This regulatory mechanism is particularly important in the control of M-Cdk activity at the onset of mitosis

Studies of the three-dimensional structures of Cdk and cyclin proteins have revealed that, in the absence of cyclin, the active site in the Cdk protein is partly obscured by a protein loop, like a stone blocking the entrance to a cave

- Cyclin binding causes the loop to move away from the active site, resulting in partial activation of the Cdk enzyme (Figure 17–12B)

Full activation of the cyclin–Cdk complex then occurs when a separate kinase, the Cdk-activating kinase (CAK), phosphorylates an amino acid near the entrance of the Cdk active site.

- This causes a small conformational change that further increases the activity of the Cdk, allowing the kinase to phosphorylate its target proteins effectively and thereby induce specific cell-cycle events (Figure 17–12C).

Positive feedback loops increase the amount of active cyclin-CDK

The Switch-like activation of CDKs ensures rapid and irreversible initiation of cell cycle events.

3. Mitosis Promoting Factor (MPF)

- Biochemical experiments had previously identified “Mitosis Promoting Factor” = MPF

Major cyclins and Cdks of vertebrates and budding yeast

- A fourth class of cyclin, cyclin G1, helps to govern the activities of the G1/S cyclins.

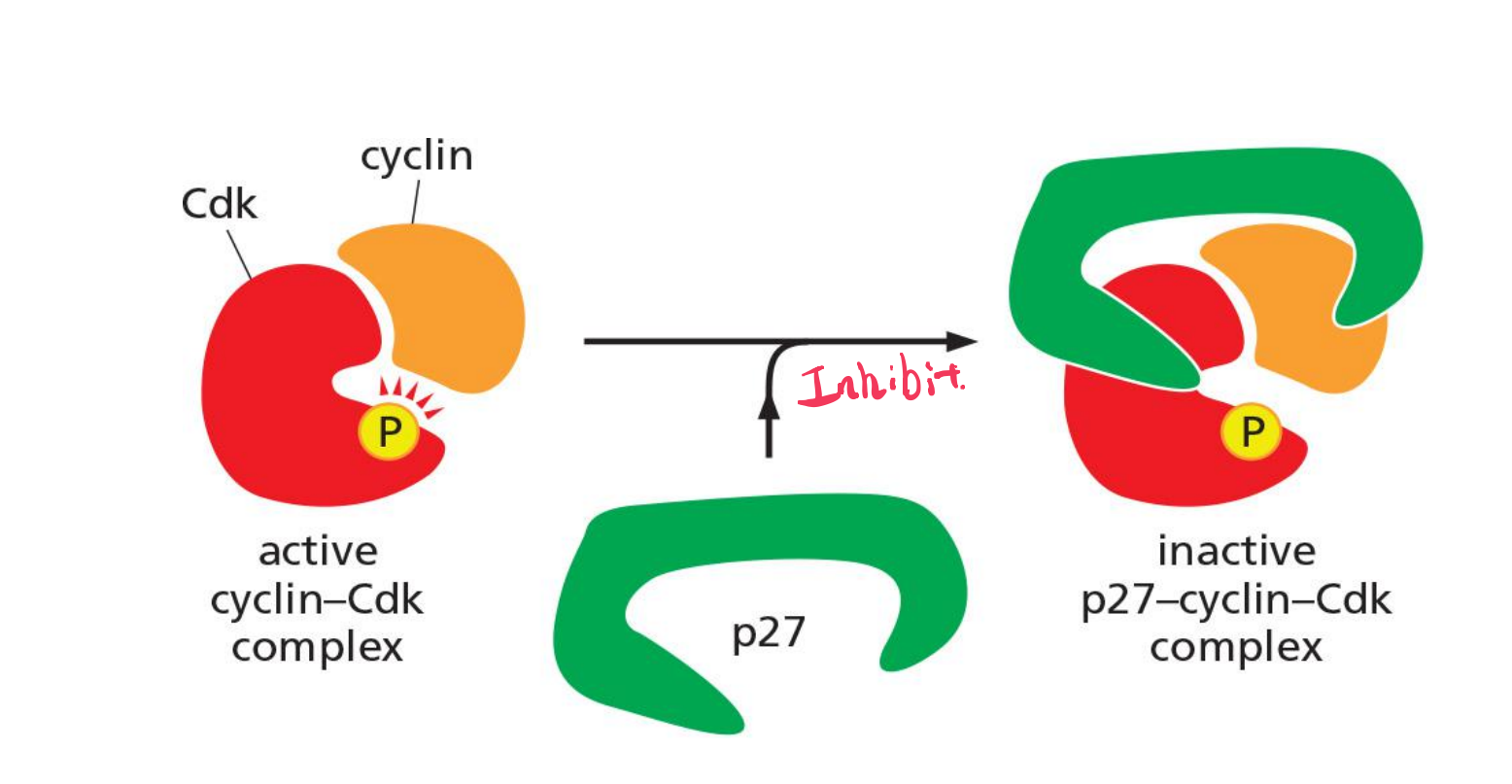

4. CKI

Cdk Activity Can Be Suppressed By Inhibitory Phosphorylation and Cdk Inhibitor Proteins (CKIs)

- The rise and fall of cyclin levels is the primary determinant of Cdk activity during the cell cycle. Several additional mechanisms, however, help control Cdk activity at specific stages of the cycle.

Phosphorylation at a pair of amino acids in the roof of the kinase active site inhibits the activity of a cyclin–Cdk complex. Phosphorylation of these sites by a protein kinase known as Wee1 inhibits Cdk activity, while dephosphorylation of these sites by a phosphatase known as Cdc25 increases Cdk activity

Binding of Cdk inhibitor proteins (CKIs) inactivates cyclin–Cdk complexes.

The three-dimensional structure of a cyclin–Cdk–CKI complex reveals that CKI binding stimulates a large rearrangement in the structure of the Cdk active site, rendering it inactive (Figure 17–14). Cells use CKIs primarily to help govern the activities of G1/Sand S-Cdks early in the cell cycle.

Inhibition of a cyclin-Cdk complex by CKI

Cdk inhibitor proteins (CKIs, e.g. p27) inactivates cyclin–Cdk complexes.

Cells use CKIs primarily to help govern the activities of G1 /S- and S-Cdks early in the cell cycle.

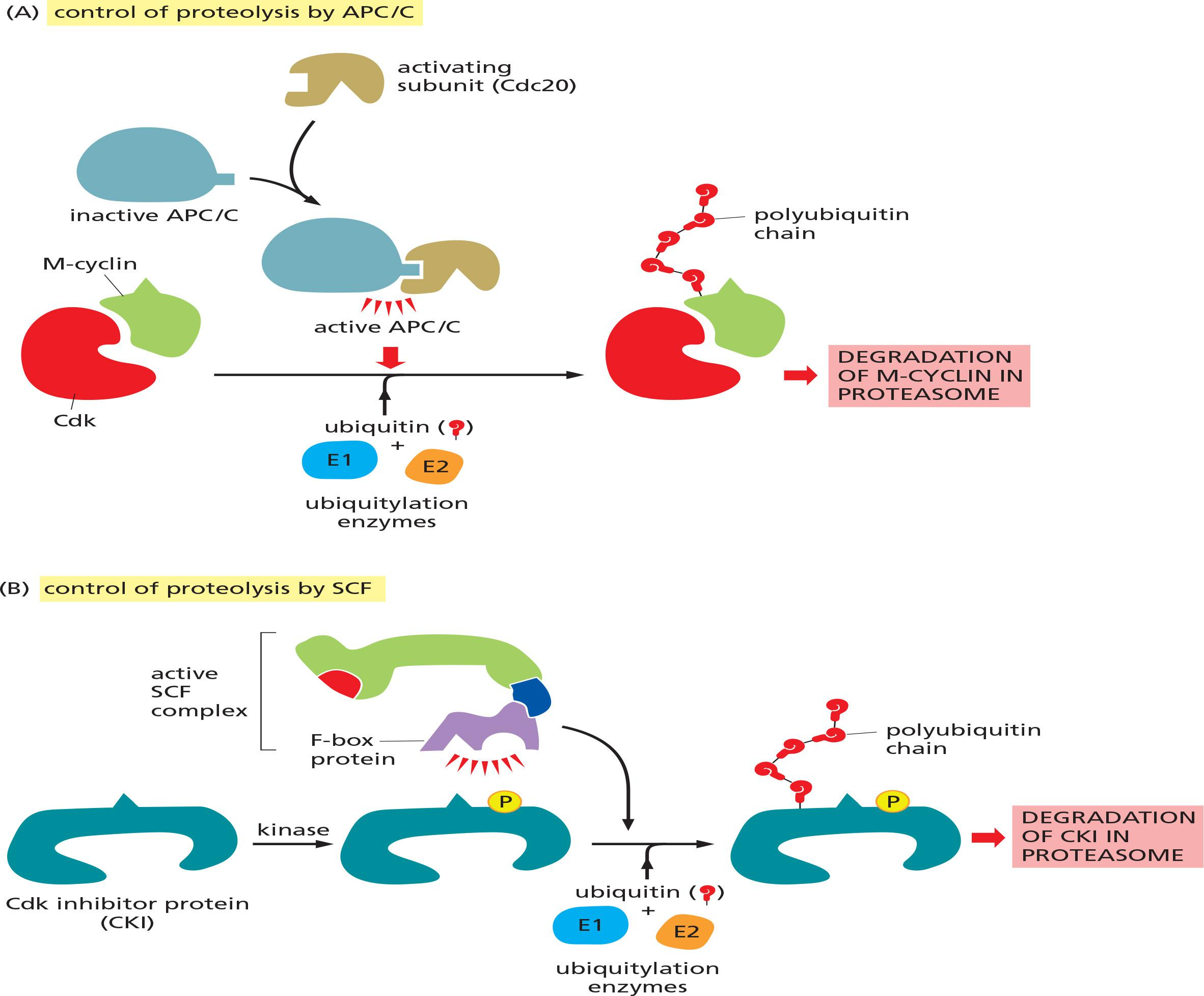

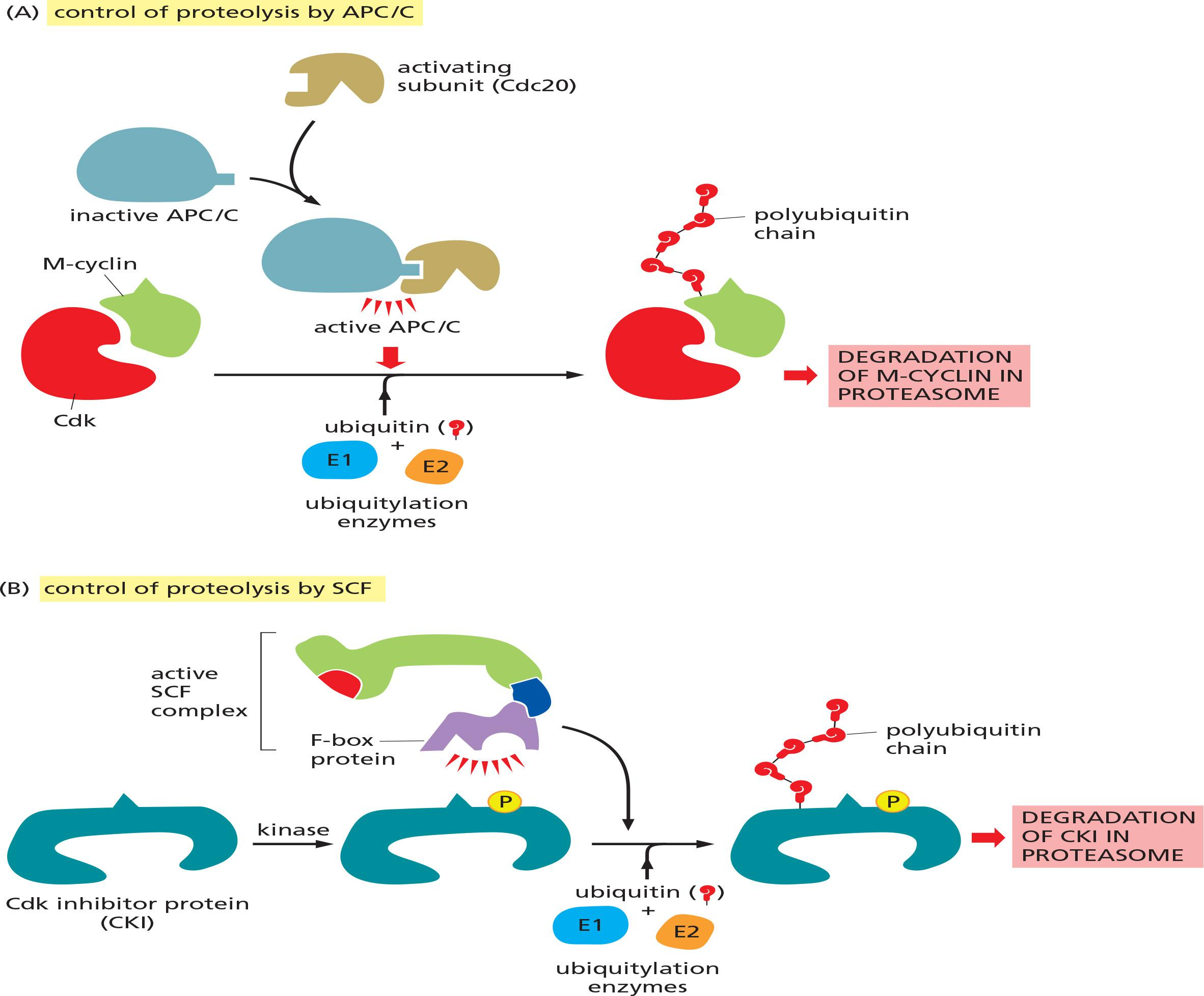

5. APC/C

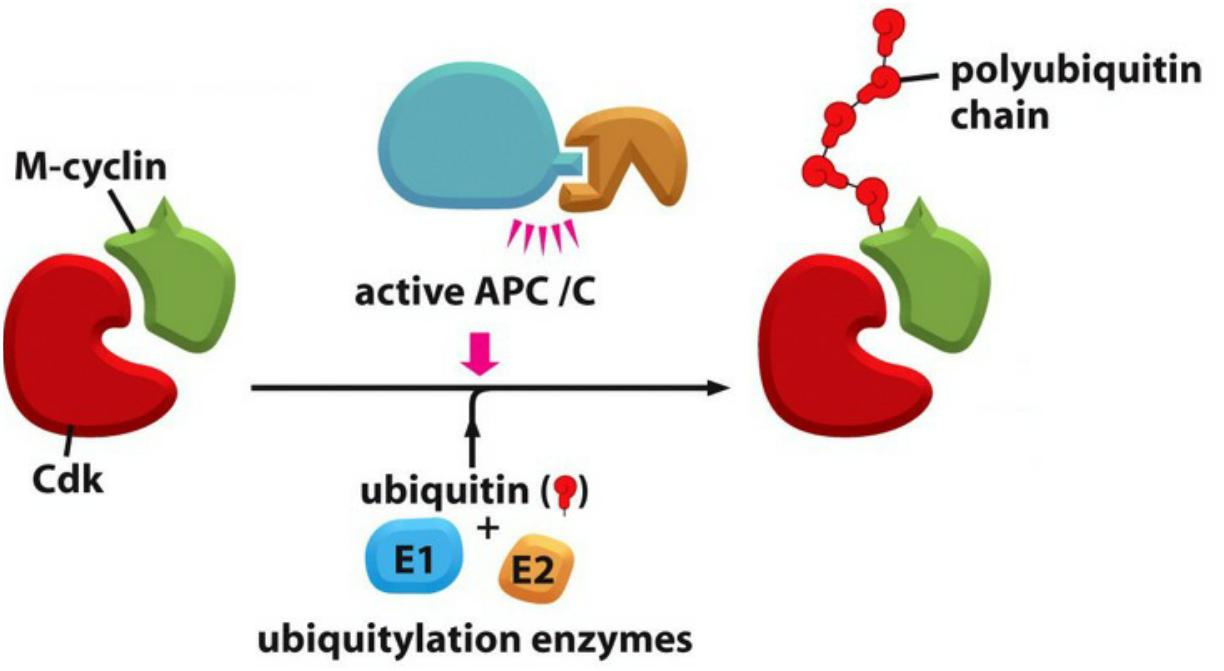

Regulated Proteolysis Triggers the Metaphase-to-Anaphase Transition

- progression through the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is triggered not by protein phosphorylation but by protein destruction, leading to the final stages of cell division.

The key regulator of the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is the anaphase-promoting complex, or cyclosome (APC/C), a member of the ubiquitin ligase family of enzymes

- They polyubiquitylate specific target proteins, resulting in their destruction in proteasomes.

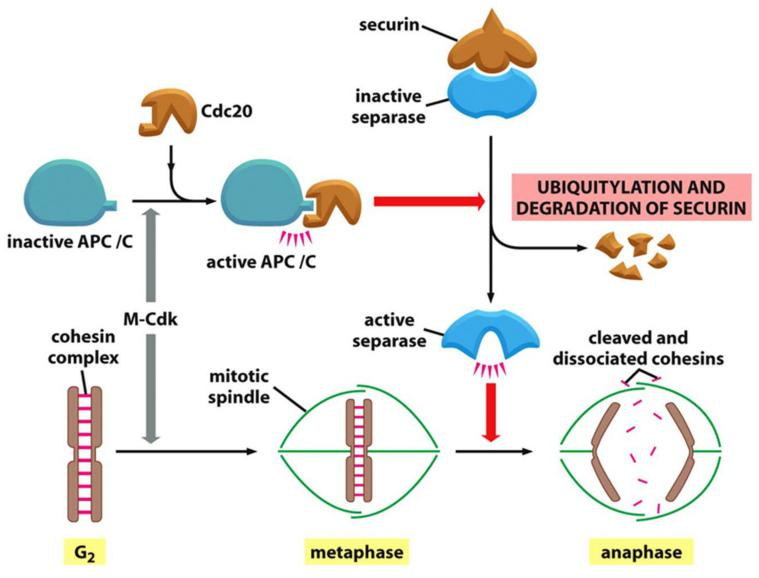

The APC/C catalyzes the ubiquitylation and destruction of two major types of proteins. The first is securin, which protects the protein linkages that hold sister-chromatid pairs together in early mitosis.

- Destruction of securin in metaphase activates a protease that separates the sisters and unleashes anaphase, as described later

The S- and M-cyclins are the second major targets of the APC/C.

- Destroying these cyclins inactivates most Cdks in the cell

As a result, the many proteins phosphorylated by Cdks from S phase to early mitosis are dephosphorylated by various phosphatases in the anaphase cell. This dephosphorylation of Cdk targets is required for the completion of M phase, including the final steps in mitosis and then cytokinesis.

Following its activation in mid-mitosis, the APC/C remains active in G1 to provide a stable period of Cdk inactivity. When G1/S-Cdk is activated in late G1, the APC/C is turned off, thereby allowing cyclin accumulation in the next cell cycle.

(The proteolytic control during the cell cycle: APC/C)

APC/C activity changes during the cell cycle, primarily as a result of changes in its association with an activating subunit—either Cdc20 in mid-mitosis or Cdh1 from late mitosis through early G1.

- These subunits help the APC/C recognize its target proteins

Ubiquitinated proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome (in the cytosol) (Lecture 12)

Major substrates of APC/C

- securin, which protects the protein linkages that hold sister-chromatid pairs together in early mitosis.

- The S- and M-cyclins

6. SCF

The cell-cycle control system also uses another ubiquitin ligase called SCF (see Figure 3–71).

It has many functions in the cell, but its major role in the cell cycle is to ubiquitylate certain CKI proteins in late G1, thereby helping to control the activation of S-Cdks and DNA replication. SCF is also responsible for the destruction of G1/S-cyclins in early S phase.

Compared to APC/C, SCF activity is constant during the cell cycle. Ubiquitylation by SCF is controlled instead by changes in the phosphorylation state of its target proteins, as F-box subunits recognize only specifically phosphorylated proteins

(The proteolytic control during the cell cycle: SCF)

Degradation of Cdk inhibitor proteins (CKIs) results the activation of cyclin-Cdk complexes

SCF is a multi-protein E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which marks CKIs for proteasomal degradation late G1, hereby helping to control the activation of S-Cdks and DNA replication.

SCF is also responsible for the destruction of G1/S-cyclins in early S phase

Summary: cell cycle control system

1. Cell-Cycle Control Also Depends on Transcriptional Regulation

Cell-cycle control depends exclusively on post-transcriptional mechanisms that involve the regulation of Cdks and ubiquitin ligases and their target proteins.

In the more complex cell cycles of most cell types, however, transcriptional control provides an important additional level of regulation. Changes in cyclin gene transcription, for example, help control cyclin levels in most cells.

2. The Cell-Cycle Control System Functions as a Network of Biochemical Switches

The Cell-Cycle Control System Functions as a Network of Biochemical Switches

When conditions for cell proliferation are right, various external and internal signals stimulate the activation of G1-Cdk, which in turn stimulates the expression of genes encoding G1/S- and S-cyclins

The resulting activation of G1/S-Cdk then drives progression through the Start transition. By mechanisms we discuss later, G1/S-Cdks unleash a wave of S-Cdk activity, which initiates chromosome duplication in S phase and also contributes to some early events of mitosis.

M-Cdk activation then triggers progression through the G2/M transition and the events of early mitosis, leading to the alignment of sister-chromatid pairs at the equator of the mitotic spindle.

Finally, the APC/C, together with its activator Cdc20, triggers the destruction of securin and cyclins, thereby unleashing sister-chromatid separation and segregation and the completion of mitosis. When mitosis is complete, multiple mechanisms collaborate to suppress Cdk activity, resulting in a stable G1 period.

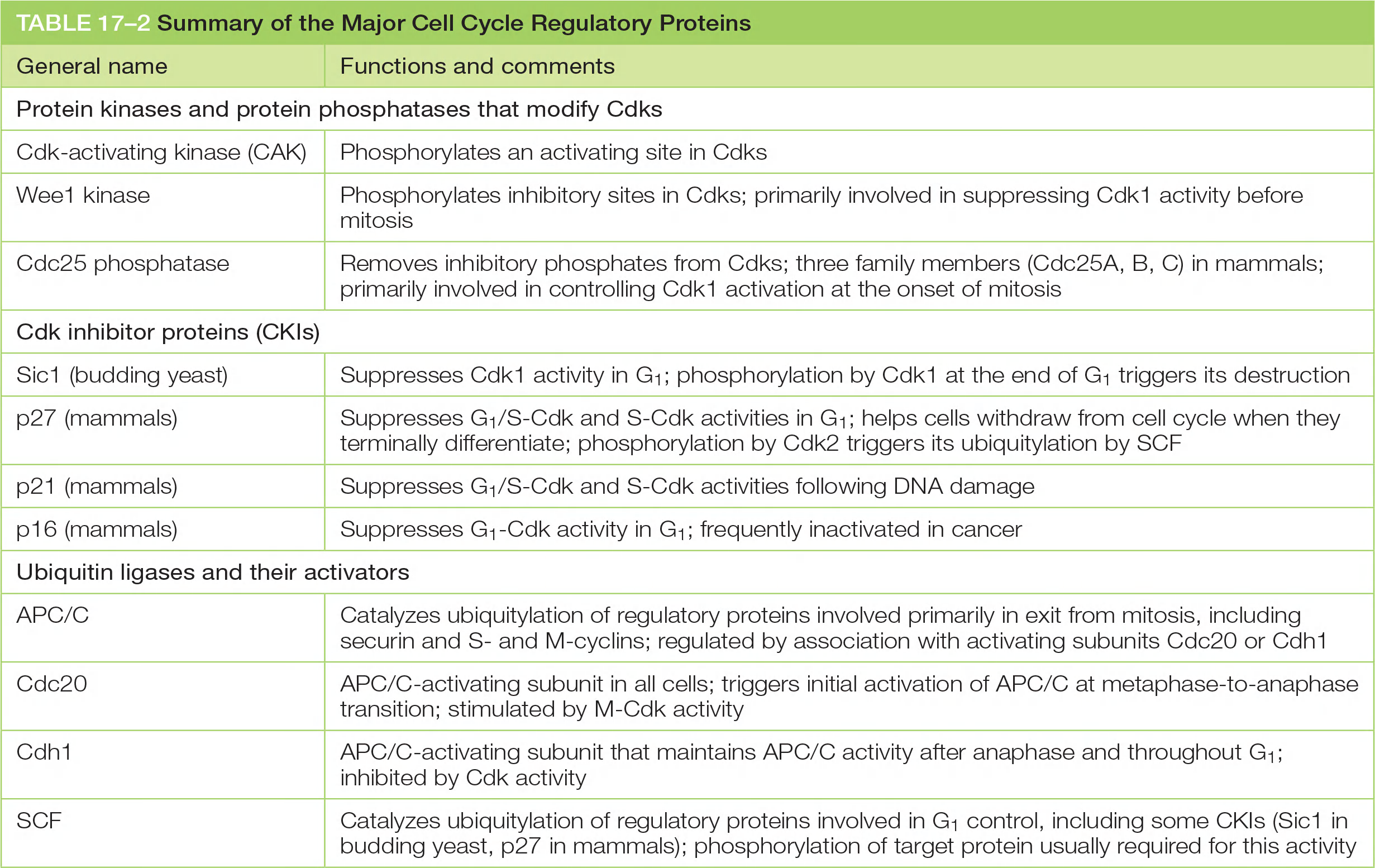

Major cell cycle regulatory proteins

| General name | Functions and comments |

|---|---|

| Protein kinases and protein phosphatases that modify Cdks | |

| Cdk-activating kinase (CAK) | Phosphorylates an activating site in Cdks |

| Wee1 kinase | Phosphorylates inhibitory sites in Cdks; primarily involved in suppressing Cdk1 activity before mitosis |

| Cdc25 phosphatase | Removes inhibitory phosphates from Cdks; three family members (Cdc25A, B, C) in mammals; primarily involved in controlling Cdk1 activation at the onset of mitosis |

| Cdk inhibitor proteins (CKIs) | |

| Sic1 (budding yeast) | Suppresses Cdk1 activity in G1; phosphorylation by Cdk1 at the end of G1 triggers its destruction |

| p27 (mammals) | Suppresses G1/S-Cdk and S-Cdk activities in G1; helps cells withdraw from cell cycle when they terminally differentiate; phosphorylation by Cdk2 triggers its ubiquitylation by SCF |

| p21 (mammals) | Suppresses G1/S-Cdk and S-Cdk activities following DNA damage |

| p16 (mammals) | Suppresses G1-Cdk activity in G1; frequently inactivated in cancer |

| Ubiquitin ligases and their activators | |

| APC/C | Catalyzes ubiquitylation of regulatory proteins involved primarily in exit from mitosis, including securin and Sand M-cyclins; regulated by association with activating subunits Cdc20 or Cdh1 |

| Cdc20 | APC/C-activating subunit in all cells; triggers initial activation of APC/C at metaphase-to-anaphase transition; stimulated by M-Cdk activity |

| Cdh1 | APC/C-activating subunit that maintains APC/C activity after anaphase and throughout G1; inhibited by Cdk activity |

| SCF | Catalyzes ubiquitylation of regulatory proteins involved in G1 control, including some CKIs (Sic1 in budding yeast, p27 in mammals); phosphorylation of target protein usually required for this activity |

三、The Cell Cycle States

S-phase

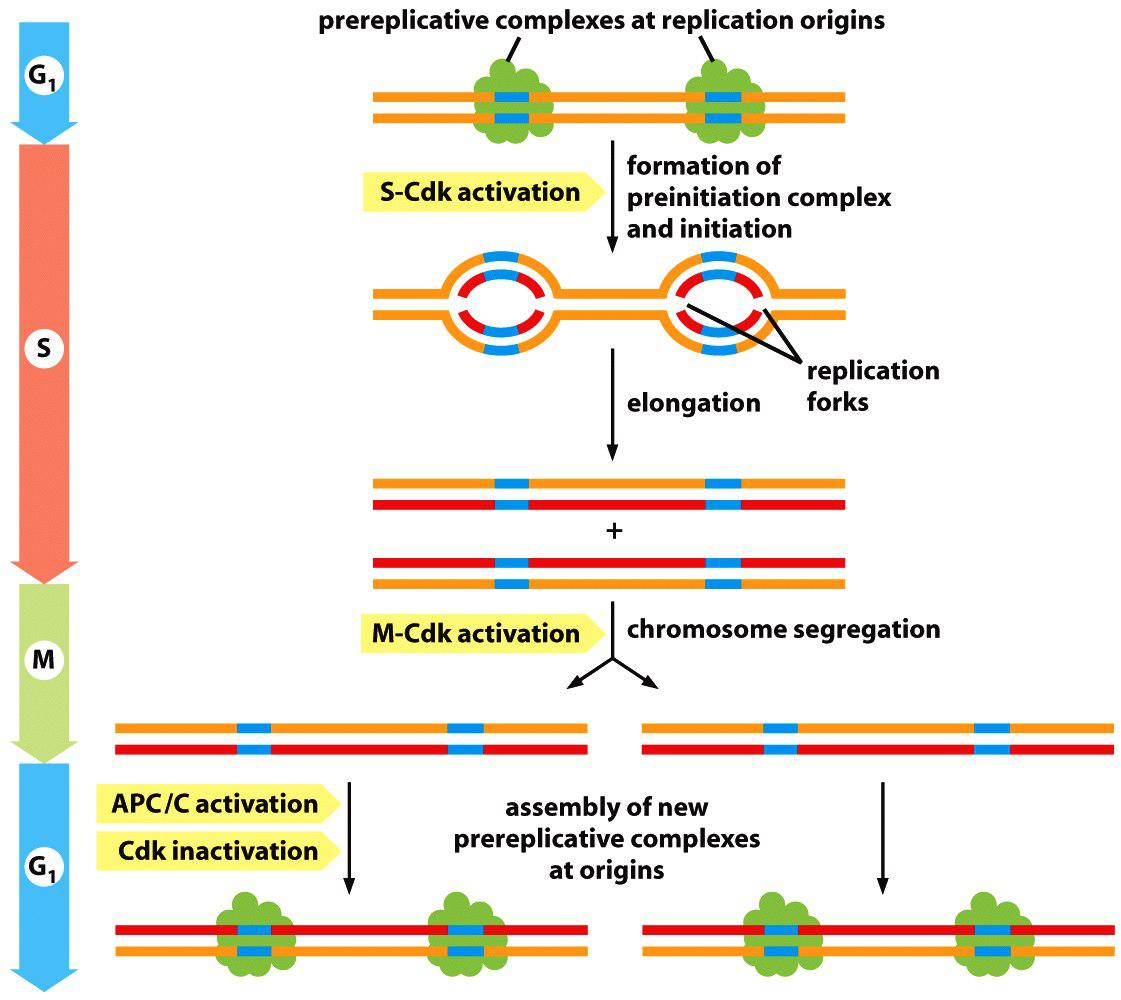

S-Cdk Initiates DNA Replication Once Per Cycle

DNA replication begins at origins of replication, which are scattered at numerous locations in every chromosome.

- During S phase, DNA replication is initiated at these origins when a DNA helicase unwinds the double helix and DNA replication enzymes are loaded onto the two single-stranded templates. This leads to the elongation phase of replication, when the replication machinery moves outward from the origin at two replication forks

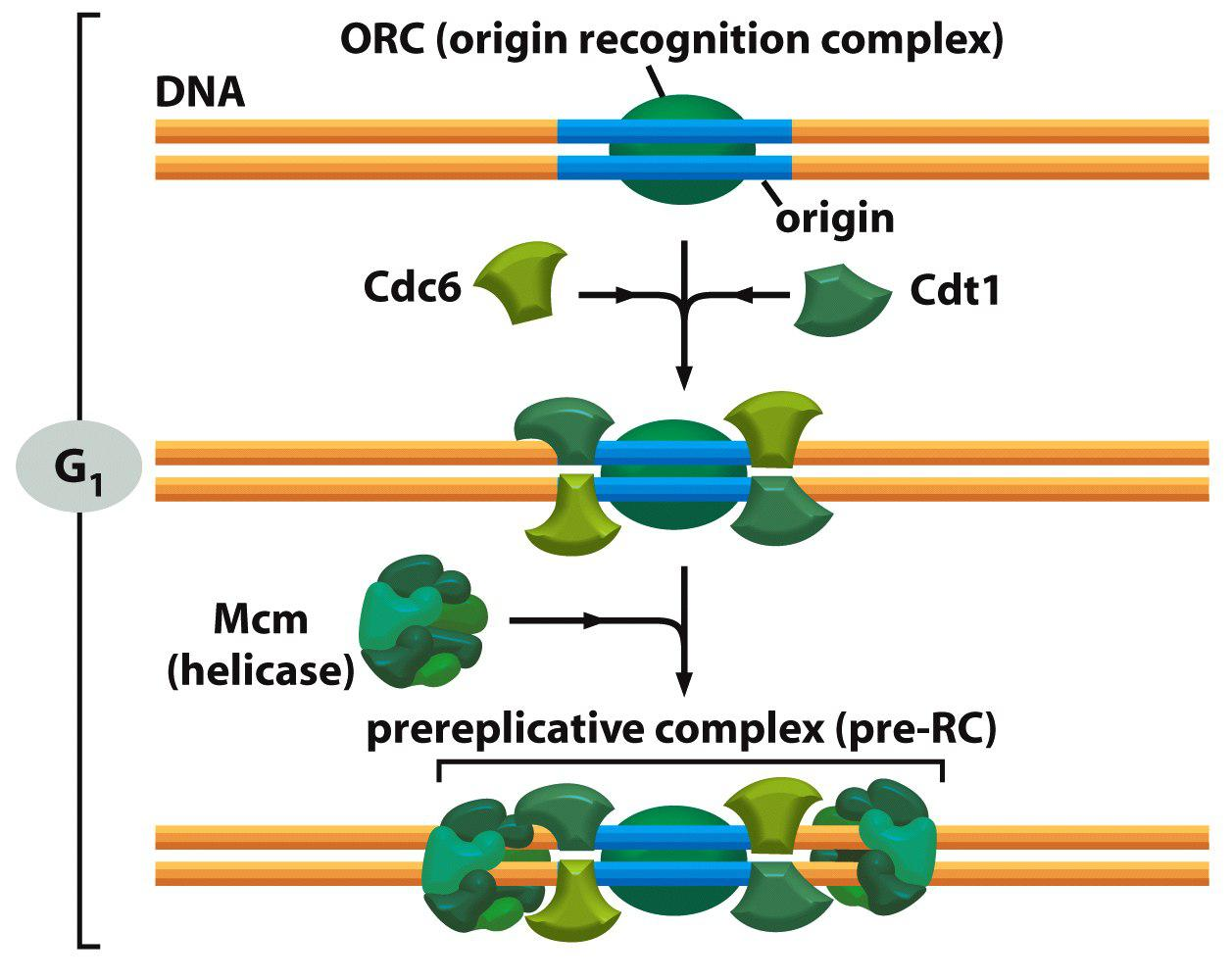

The first step occurs in late mitosis and early G1, when a pair of inactive DNA helicases is loaded onto the replication origin, forming a large complex called the prereplicative complex or preRC.

- This step is sometimes called licensing of replication origins because initiation of DNA synthesis is permitted only at origins containing a preRC.

- The second step occurs in S phase, when the DNA helicases are activated, resulting in DNA unwinding and the initiation of DNA synthesis

- Once a replication origin has been fired in this way, the two helicases move out from the origin with the replication forks, and that origin cannot be reused until a new preRC is assembled there at the end of mitosis. As a result, origins can be activated only once per cell cycle.

S phase: DNA replication once and only once

Most important questions:

- How to ensure that DNA is replicated only once?

- How to get the timing right?

Answer:

- Chromosome duplication is a “two-step” procedure:

- 1st : initiation/priming of the DNA

- 2nd : start of the replication

Both processes are temporally separated and tightly controlled by Cdks and APC/C:

- Initiation in late M-phase but start in the S-phase

1. Cyclin CDK complexes trigger major events in DNA replication

ORC: Origin recognition complex (ORC) binds to replication origin

ORC recruits Cdc6 and Cdt1 to form pre-replicative complex (pre-RC).

In late mitosis and early G1, the proteins Cdc6 and Cdt1 collaborate with the ORC to load the inactive DNA helicases around the DNA next to the origin. The resulting large complex is the preRC, and the origin is now licensed for replication.

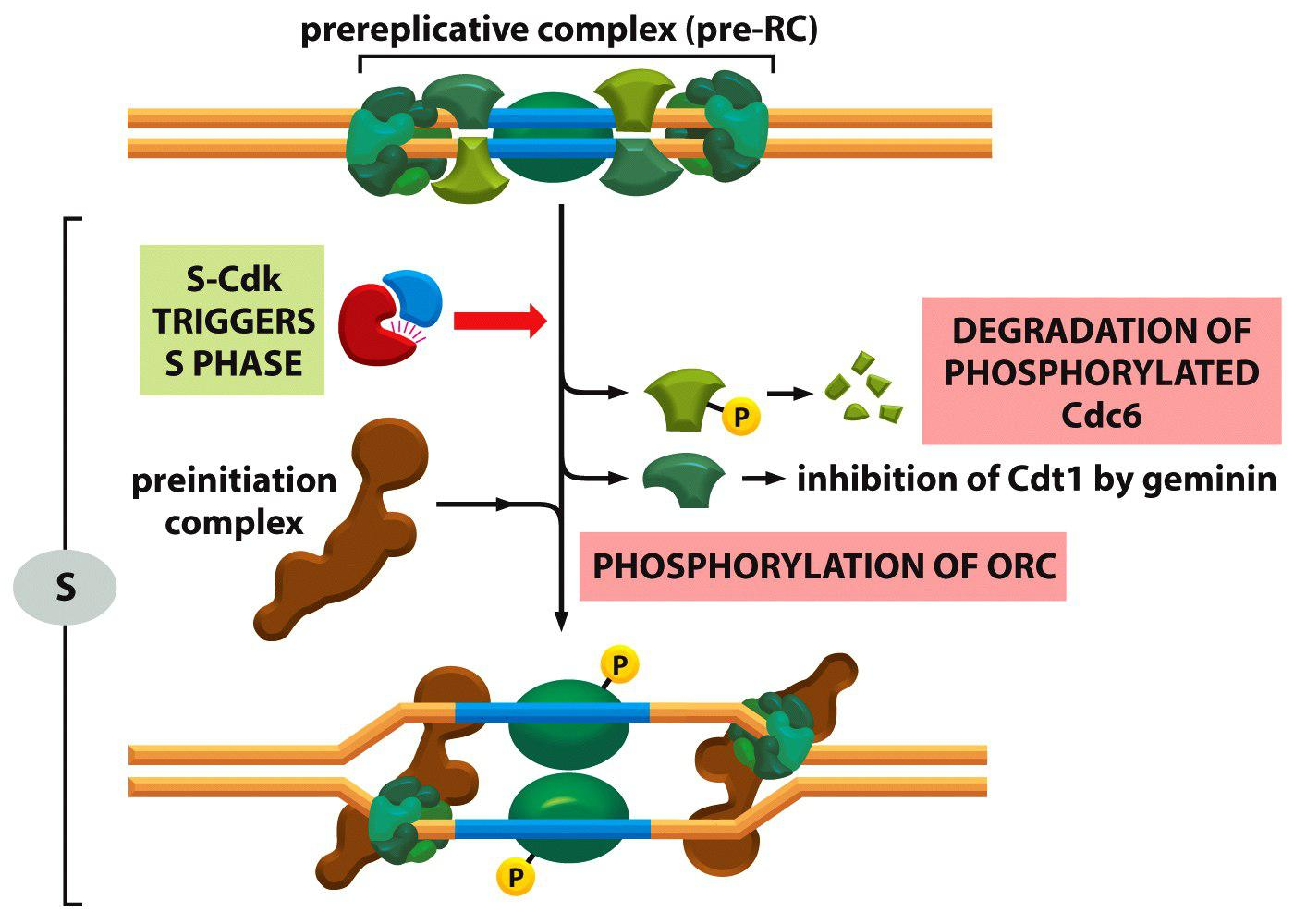

At the onset of S phase, S-Cdk triggers origin activation by phosphorylating specific initiator proteins, which then nucleate the assembly of a large protein complex that activates the DNA helicase and recruits the DNA synthesis machinery

Another protein kinase called DDK is also activated in S phase and helps drive origin activation by phosphorylating specific subunits of the DNA helicase.

Cdc6 and Cdt1 recruit a helicase (MCM2-7) that will unwind the DNA to allow it to be replicated.

Active cyclin S-Cdk phosphorylates several proteins that lead to assembly of a replication complex that starts DNA replication.

- Cyclin S-Cdk also phosphorylates the ORC to inactive it and Cdc6 which triggers its degradation and disassembles the pre-RC.

At the same time as S-Cdk initiates DNA replication, several mechanisms prevent assembly of new preRCs. S-Cdk phosphorylates and thereby inhibits the ORC and Cdc6 proteins. Inactivation of the APC/C in late G1 also helps turn off preRC assembly

1st initiation: formation of the pre-RC: liscening

pre-RC formation is promoted by APC/C but inhibited by Cdks activity

Late M/early G1: low Cdk activity but high APC/C activity: → pre-RC is formed.

In late mitosis and early G1, the APC/C triggers the destruction of a Cdt1 inhibitor called geminin, thereby allowing Cdt1 to be active. When the APC/C is turned off in late G1, geminin accumulates and inhibits the Cdt1 that is not associated with DNA.

In these various ways, preRC formation is prevented from S phase to mitosis, thereby ensuring that each origin is fired only once per cell cycle.

- Firstly, cdc6 and cdt1 associate with ORC

- (Cdt1 inhibitor geminin is degraded by APC/C in mitosis and G1 phase)

- Secondly, MCM ring loaded onto DNA

- Thirdly, pre-RC is formed: MCM/cdc6/cdt1/ORC

2nd: formation of the pre-initiation complex

Firstly: S-Cdk triggers phosphorylation and degradation of Cdc6

Secondly: If S-Cdk is high while APC/C is low in activity, geminin is stabilized)

Thirdly: S-Cdk phosphorylates ORC and loads pre-initiation complex onto ORC to initiate DNA replication.

Conclusion: The in M/G1 assembled pre-replicative complex (pre-RC) is destroyed in S-phase and cannot be reassembled before reaching again M/G1.

Chromosome Duplication Requires Duplication of Chromatin Structure

The production of chromatin proteins increases during S phase to provide the raw materials needed to package the newly synthesized DNA.

Most importantly, S-Cdks stimulate a large increase in the synthesis of the four histone subunits that form the histone octamers at the core of each nucleosome.

These subunits are assembled into nucleosomes on the DNA by nucleosome assembly factors, which typically associate with the replication fork and distribute nucleosomes on both strands of the DNA as they emerge from the DNA synthesis machinery.

Chromatin packaging helps to control gene expression.

In some parts of the chromosome, the chromatin is highly condensed and is called heterochromatin, whereas in other regions it has a more open structure and is called euchromatin (常染色质)

These differences in chromatin structure depend on a variety of mechanisms, including modification of histone tails and the presence of non-histone proteins

- During DNA synthesis, histone-modifying enzymes and various non-histone proteins are probably deposited onto the two new DNA strands as they emerge from the replication fork, and these proteins are thought to reproduce the local chromatin structure of the parent chromosome

Summary

Summary: APC/C-dependent temporal separation of DNA priming for replication in G1 and the start of the replication in S-phase

Summary:

- Pre-replication complex (pre-RC) “prime and licensing” is formed by APC/C in late M and early G1 when APC/C activity is high (→remember its function in the cell cycle control).

- Pre-initiation complex (DNA unwinding, replication) is activated by S-Cdk in S-phase when APC/C activity is low, pre-RC is dismantled and cannot assemble again.

- Levels of S-Cdks and M-Cdks remain high until after late mitosis, when APC/C regains its activity and targets the cyclins for degradation, and starts the next round of pre-RC formation.

2. Cohesins Tether Sister Chromatids

Cohesins tether sister chromatids to prevent premature separation

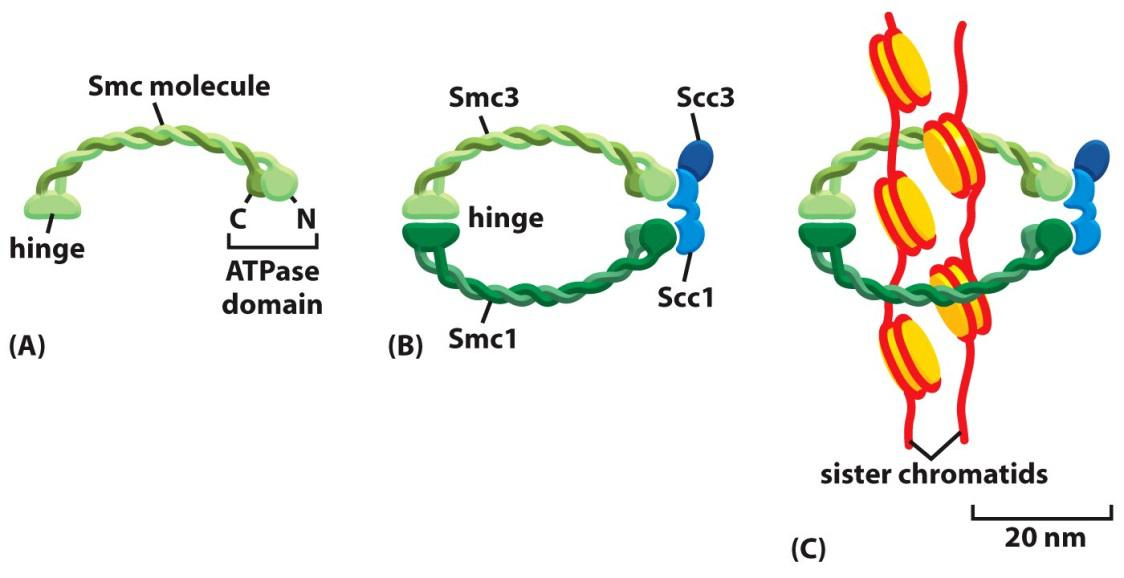

Sister-chromatid cohesion depends on a large protein complex called cohesin, which is deposited at many locations along the length of each sister chromatid as the DNA is replicated in S phase

- Two of the subunits of cohesin are members of a large family of proteins called SMC proteins (for Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes).

Cohesin forms giant ringlike structures, and it has been proposed that these surround the two sister chromatids

- Cohesins:

- 2 homodimers Smc3 (structural maintenance of chromosomes)

- 2 homodimers Smc1

Cohesins are deposited at many locations along the length of each sister chro

matids

Prevent drifting apart for sister chromatids after DNA replication.

DNA catenation is intertwining of sister DNA molecules which can be resolved by DNA topoisomerase II

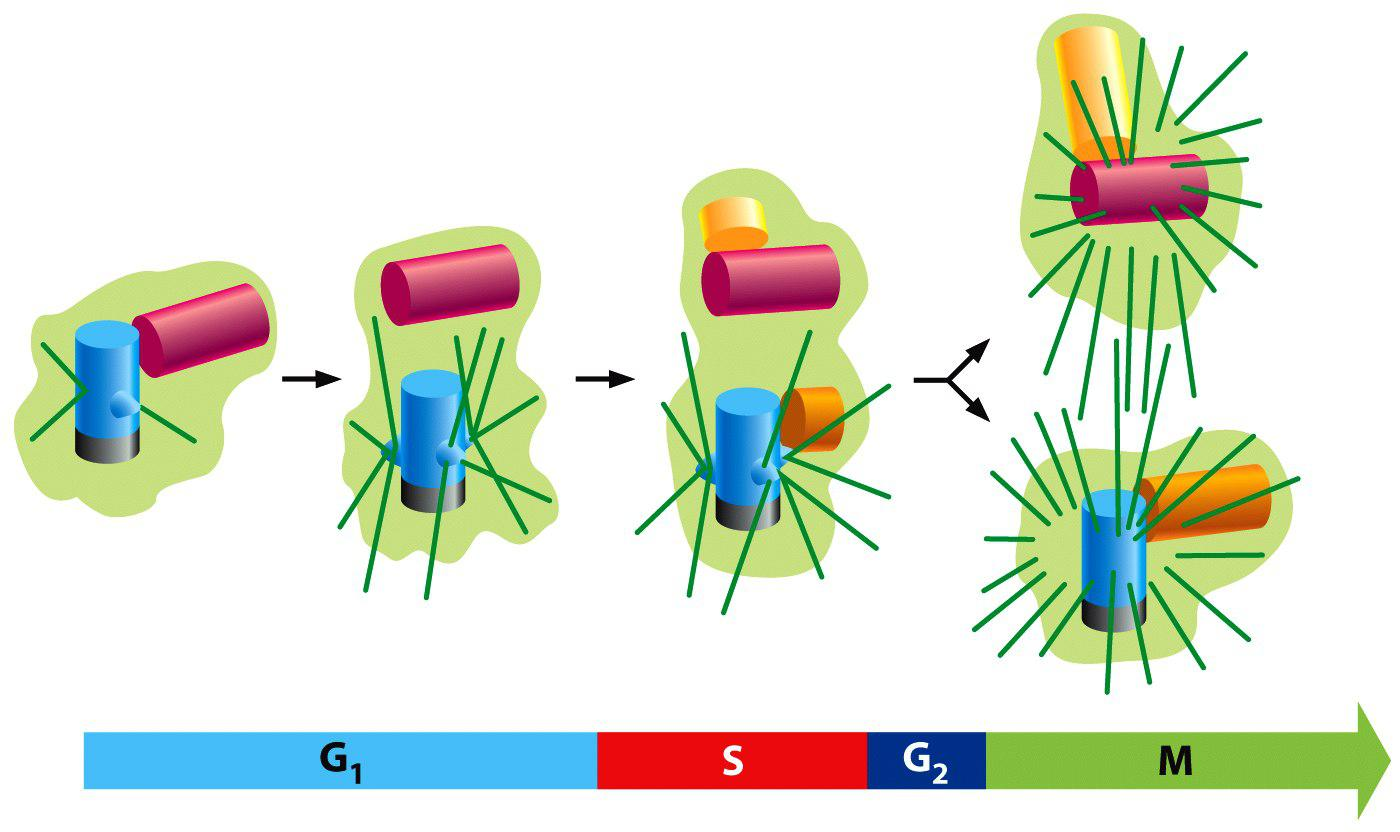

3. Centriole Replication

centriole replication also happens during S phase

In G1, the two centrioles of centrosome separate by a few micrometers.

During S phase, a daughter centriole begins to grow near the base of each mother centriole and at a right angle to it.

The elongation of the daughter centriole is usually completed in G2.

The two centriole pairs remain close together in a single centrosomal complex till M-phase and then nucleates its own array of microtubules

Mitosis

Mitosis: assembly the spindle and chromosome segregation

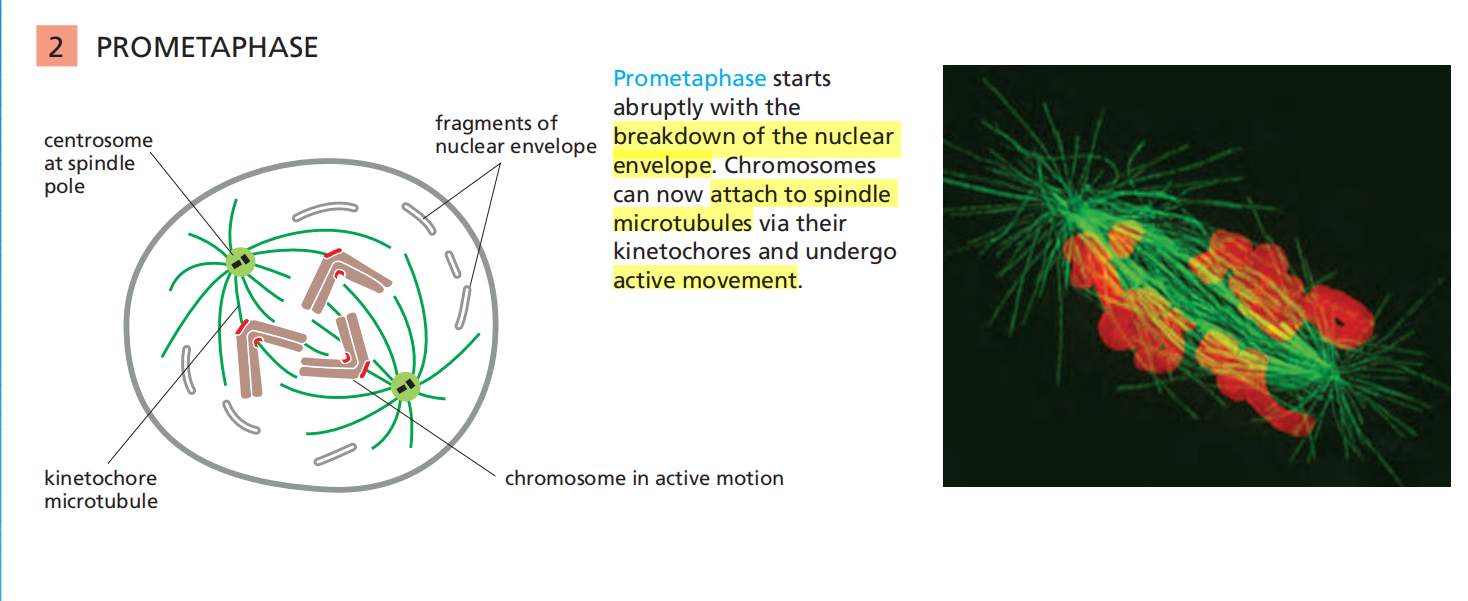

Mitosis is traditionally divided into five stages—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—defined primarily on the basis of chromosome behavior as seen in a microscope.

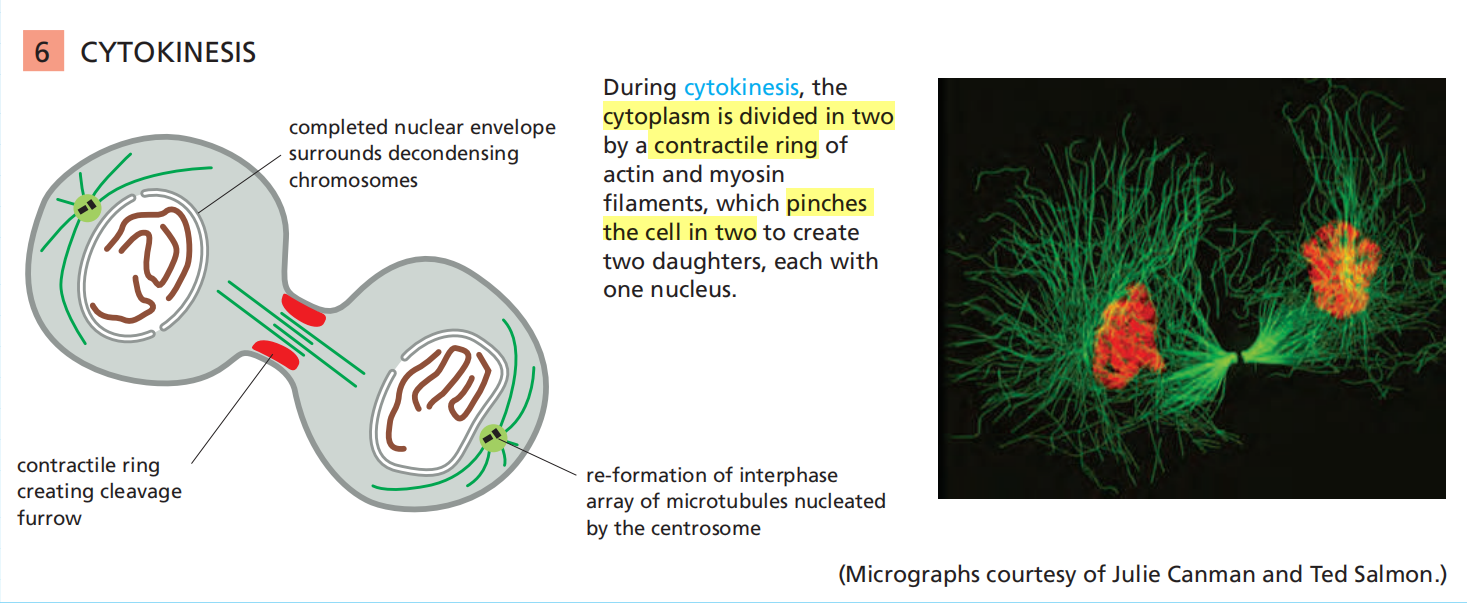

As mitosis is completed, the second major event of M phase—cytokinesis—divides the cell into two halves, each with an identical nucleus.

From a regulatory point of view, mitosis can be divided into two major parts, each governed by distinct components of the cell-cycle control system

- First, an abrupt increase in M-Cdk activity at the G2/M transition triggers the events of early mitosis (prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase). During this period, M-Cdk and several other mitotic protein kinases phosphorylate a variety of proteins, leading to the assembly of the mitotic spindle and its attachment to the sister-chromatid pairs

- The second major part of mitosis begins at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, when the APC/C triggers the destruction of securin, liberating a protease that cleaves cohesin and thereby initiates separation of the sister chromatids.

- The APC/C also promotes the destruction of cyclins, which leads to Cdk inactivation and the dephosphorylation of Cdk targets, which is required for all events of late M phase, including the completion of anaphase, the disassembly of the mitotic spindle, and the division of the cell by cytokinesis

1. Entry into Mitosis

Early events in Mitosis: M-Cdk drives entry into mitosis

M-Cdk (complex of Cdk1 and M-cyclin) and its effectors:

- Induce assembly of mitotic spindle and its attachment to the sister chromatids pairs

- Trigger chromosome condensation

- Breakdown of nuclear envelope

- Rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and the Golgi

How? Not fully understood; not all substrates for M-Cdk have been identified yet

2. Activation of M-Cdk Complex - Mitosis Onset

M-Cdk Drives Entry Into Mitosis

- At a minimum, M-Cdk must induce the assembly of the mitotic spindle and ensure that each sister chromatid in a pair is attached to the opposite pole of the spindle.

- It also triggers chromosome condensation, the large-scale reorganization of the intertwined sister chromatids into compact, rodlike structures. In animal cells, M-Cdk also promotes the breakdown of the nuclear envelope and rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton and the Golgi apparatus.

M-Cdk does not act alone to phosphorylate key proteins involved in early mitosis

- Two additional families of protein kinases, the Polo-like kinases and the Aurora kinases, also make important contributions to the control of early mitotic events.

- The Polo-like kinase Plk, for example, is required for the normal assembly of a bipolar mitotic spindle, in part because it phosphorylates proteins involved in separation of the spindle poles early in mitosis.

The Aurora kinase Aurora-A also helps control proteins that govern the assembly and stability of the spindle, whereas Aurora-B controls attachment of sister chromatids to the spindle,

Dephosphorylation Activates M-Cdk at the Onset of Mitosis

- M-Cdk activation begins with the accumulation of M-cyclin (cyclin B in vertebrate cells)

In embryonic cell cycles, the synthesis of M-cyclin is constant throughout the cell cycle, and M-cyclin accumulation results from the high stability of the protein in interphase

M-cyclin synthesis increases during G

2and M, owing primarily to an increase in M-cyclin gene transcription.

- The increase in M-cyclin protein leads to a corresponding accumulation of M-Cdk

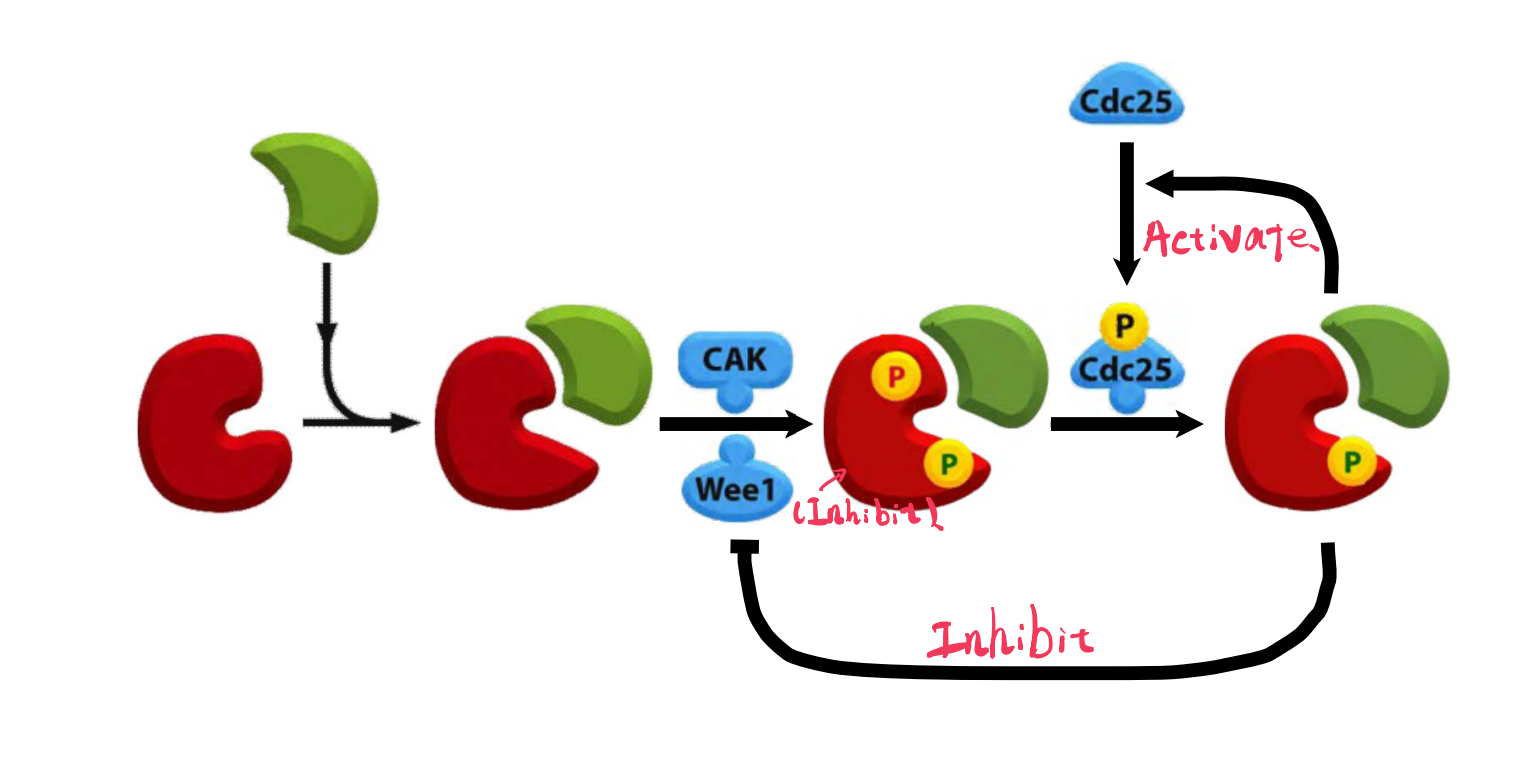

Although the Cdk in these complexes is phosphorylated at an activating site by the Cdk-activating kinase (CAK), as discussed earlier, the protein kinase Wee1 holds it in an inactive state by inhibitory phosphorylation at two neighboring sites

- Thus, by the time the cell reaches the end of G

2, it contains an abundant stockpile of M-Cdk that is primed and ready to act but is suppressed by phosphates that block the active site of the kinaseWhat, then, triggers the activation of the M-Cdk stockpile? Cdc25 can also be activated, at least in part, by its target, M-Cdk. M-Cdk may also inhibit the inhibitory kinase Wee1.

- The crucial event is the activation of the protein phosphatase Cdc25, which removes the inhibitory phosphates that restrain M-Cdk

- At the same time, the inhibitory activity of the kinase Wee1 is suppressed, further ensuring that M-Cdk activity increases.

The ability of M-Cdk to activate its own activator (Cdc25) and inhibit its own inhibitor (Wee1) suggests that M-Cdk activation in mitosis involves positive feedback loops

Assembly of the complex from Cdk1 and M-cyclin (inactive!)

Phosphorylation of inhibitory & activating sites by Wee1 & CAK (complex remains inactive!)

Activation of the phosphatase Cdc25

- Active Cdc25 activates M-Cdk by removing the inhibitory phosphate (positive feedback)

- Simultaneous inhibition of the Cdk-inhibitory kinase Wee1 (positive feedback)

3. The Stages of M-Phase

Prophase

Prometaphase

Metaphase

Anaphase

Telophase

Cytokinesis

4. Some Details of these M-Phase States

Sister Chromatin Condensation

The mitotic chromosome:

- Two sister chromatids joined along their length.

- The constricted regions hint to the centromer

(1) Condensin

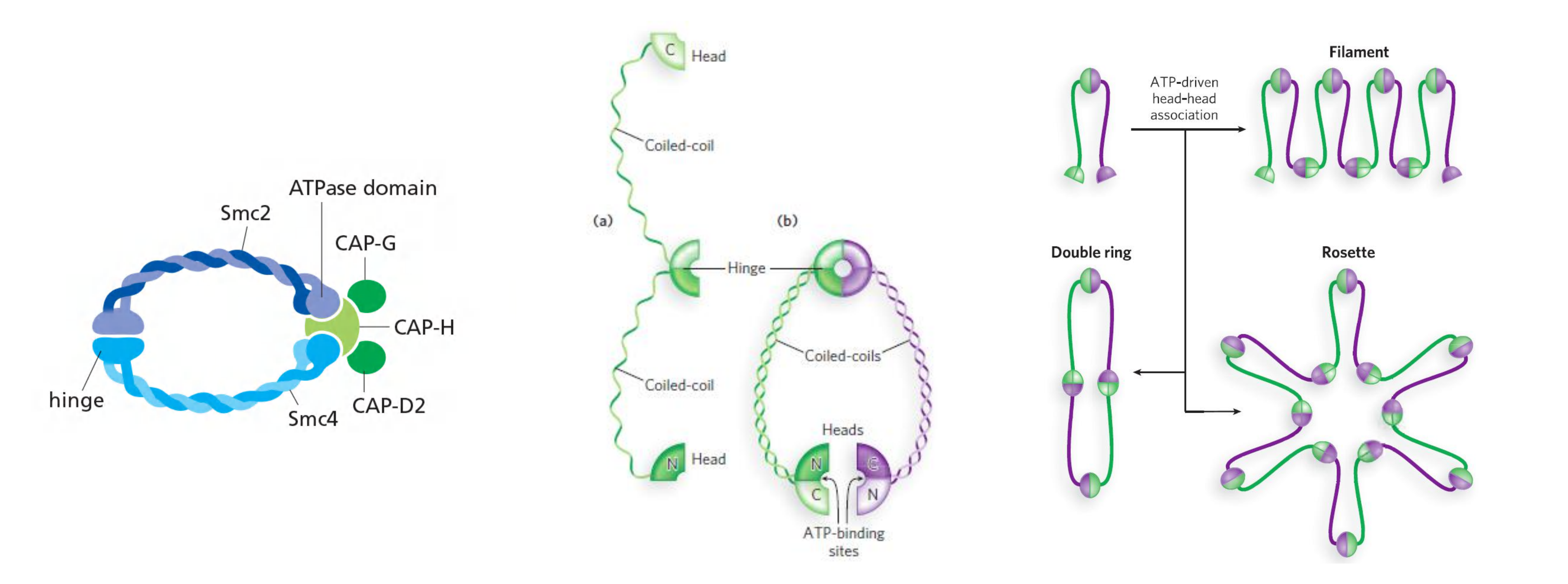

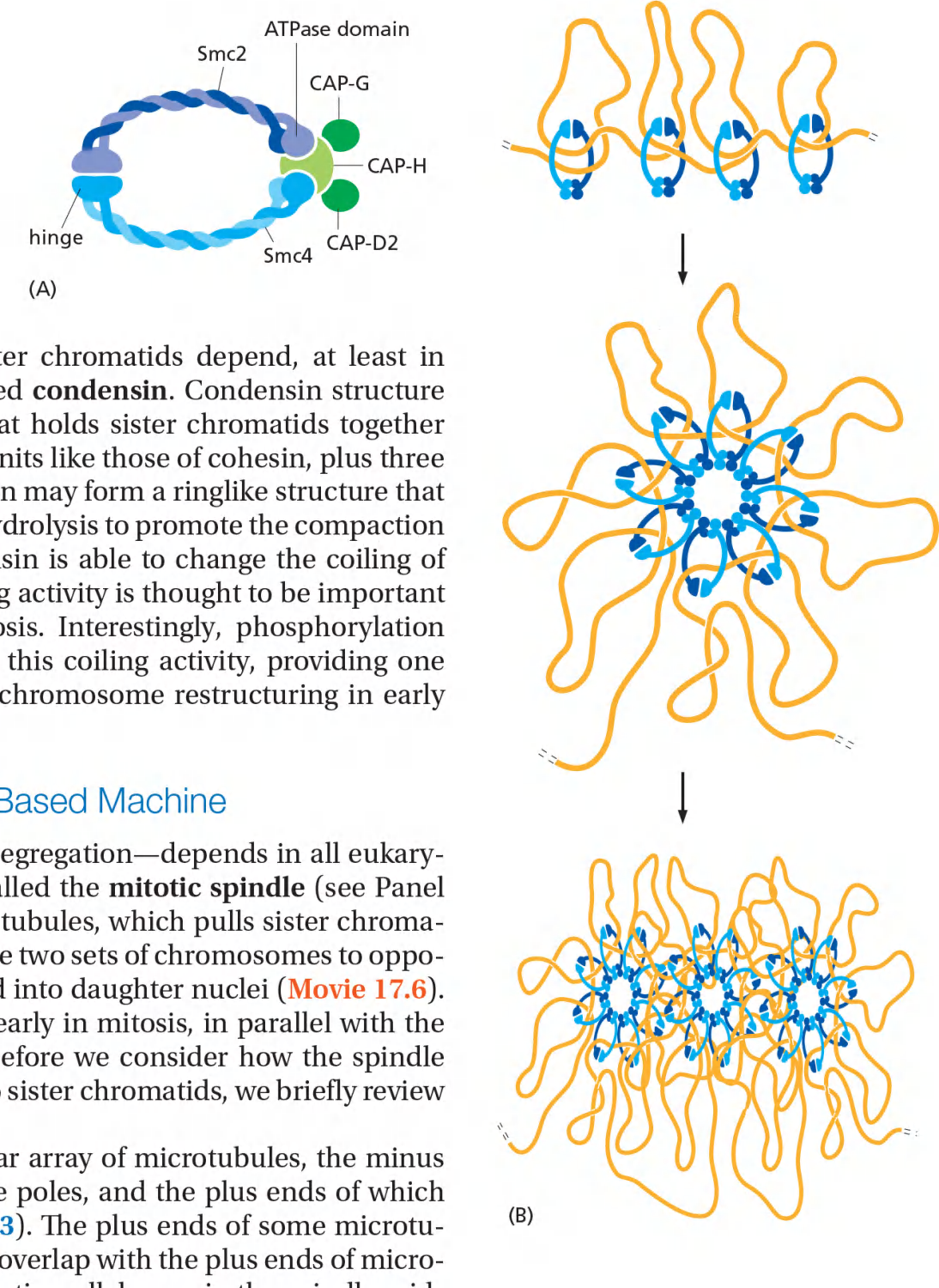

The condensation and resolution of sister chromatids depend, at least in part, on a five-subunit protein complex called condensin

Condensin may form a ringlike structure that somehow uses the energy provided by ATP hydrolysis to promote the compaction and resolution of sister chromatids.

Phosphorylation of condensin subunits by M-Cdk stimulates this coiling activity, providing one mechanism by which M-Cdk may promote chromosome restructuring in early mitosis.

Condensin Helps Configure Duplicated Chromosomes for Separation

These chromosomal changes involve two processes:

chromosome condensation, in which the chromatids are dramatically compacted; and sister-chromatid resolution, whereby the two sisters are resolved into distinct, separable units

(1. 染色体浓缩,其中染色单体显着压缩。 2. 姐妹染色单体解析,从而将两个姐妹分解为不同的可分离单元)

Resolution results from the decatenation of the sister DNAs, accompanied by the partial removal of cohesin molecules along the chromosome arms.

As a result, when the cell reaches metaphase, the sister chromatids appear in the microscope as compact, rodlike structures that are joined tightly at their centromeric regions and only loosely along their arms.

Condensin might form a ring-like structure and ATP hydrolysis to drive condensation

Condensins are phosphorylated and activated by M-Cdk

Possible roles of condensin in chromosome condensation:

- It is not clear how condensing restructures and compacts the chromosome DNA.

- It may form a ring structure that encircles loops of DNA within each sister chromatid….

Disassembly of the nuclear envelope

M-Cdk and other mitotic protein kinases phosphorylate components of the nuclear pore complex and laminin.

This promotes the disassembly of the nuclear envelope and of the nuclear lamina (the structural compound of the envelope).

The nuclear envelope disintegrates into vesicles and ER.

- Attachment of sister-chromatid pairs to the spindle requires disassembly of the nuclear envelope

The Completion of Spindle Assembly in Animal Cells Requires Nuclear-Envelope Breakdown

Nuclear-envelope breakdown is a complex, multistep process, which is thought to begin when M-Cdk phosphorylates several subunits of the nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope. This phosphorylation initiates the disassembly of nuclear pore complexes and their dissociation from the envelopes

M-Cdk also phosphorylates components of the nuclear lamina, the structural framework beneath the envelope.

- The phosphorylation of these lamina components and of several inner-nuclear-envelope proteins leads to disassembly of the nuclear lamina and the breakdown of the envelope membranes into small vesicles.

Chromosome Separation

Microtubule-based spindle mediates chromosome separation during mitosis

- Taxol (紫杉酚) prevents depolymerization of microtubules, inhibiting cell division

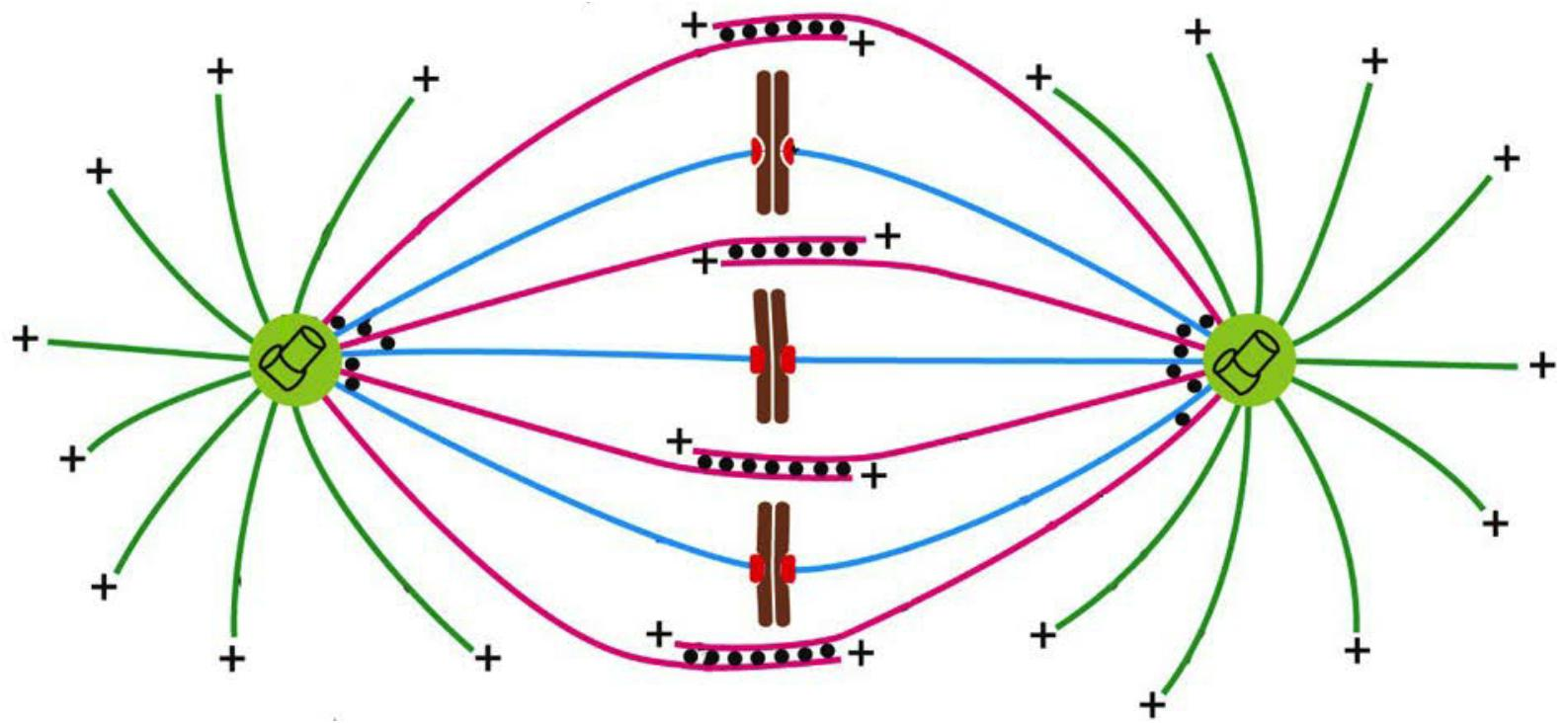

The Mitotic Spindle Is a Microtubule-Based Machine

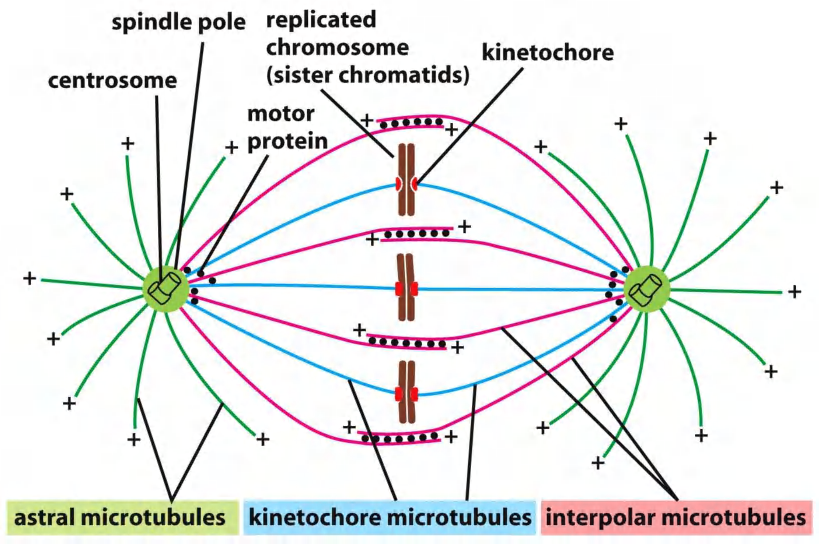

The central event of mitosis—chromosome segregation—depends in all eukaryotes on a complex and beautiful machine called the mitotic spindle

- The spindle is a bipolar array of microtubules, which pulls sister chromatids apart in anaphase, thereby segregating the two sets of chromosomes to opposite ends of the cell

The core of the mitotic spindle is a bipolar array of microtubules, the minus ends of which are focused at the two spindle poles, and the plus ends of which radiate outward from the poles

The plus ends of some microtubules—called the interpolar microtubules— overlap with the plus ends of microtubules from the other pole, resulting in an antiparallel array in the spindle mid-zone. The plus ends of other microtubules—the kinetochore microtubules—are attached to sister-chromatid pairs at large protein structures called kinetochores, which are located at the centromere of each sister chromatid.

Finally, many spindles also contain astral microtubules that radiate outward from the poles and contact the cell cortex, helping to position the spindle in the cell.

M-Cdk Initiates Spindle Assembly in Prophase

Spindle assembly begins in early mitosis, when the two centrosomes move apart along the nuclear envelope, pulled by dynein motor proteins that link astral microtubules to the cell cortex

(1) Microtubules

Three types of microtubules comprise the mitotic spindle

- astral microtubules

- kinetochore microtubules

- interpolar microtubules

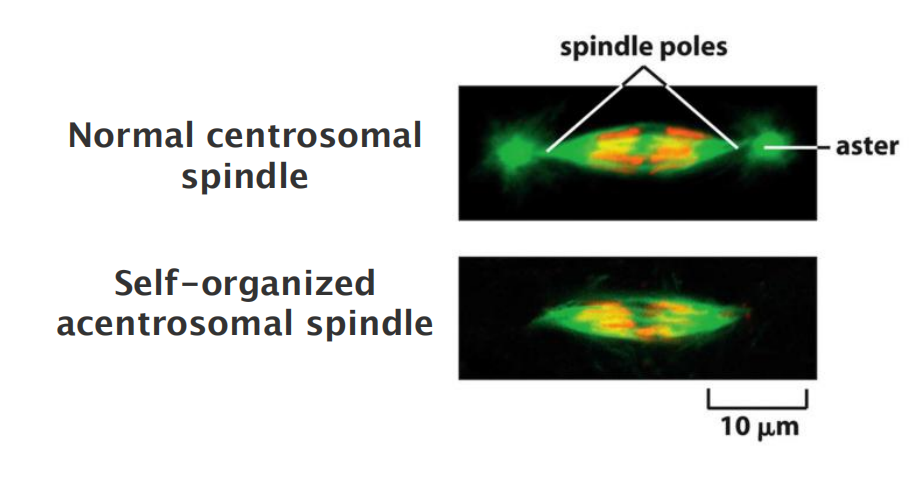

- Two different mechanisms ensure bipolarity of spindles:

- Centrosome-dependent spindle formation

- Acentrosomal “self-organizing” of the spindle formation

- → Chromosome and motor proteins dependent

- Acentrosomal “self-organizing” of the spindle formation

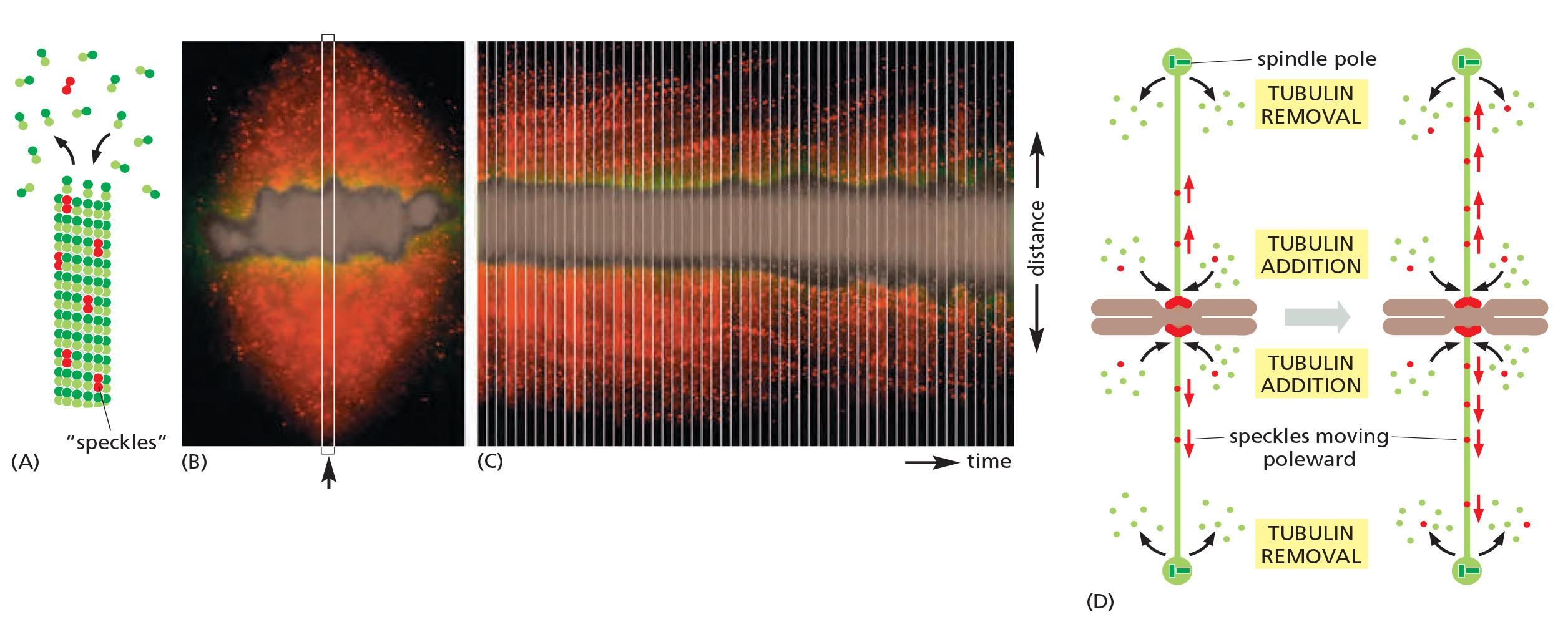

Microtubule instability in mitosis

Microtubule Instability Increases Greatly in Mitosis

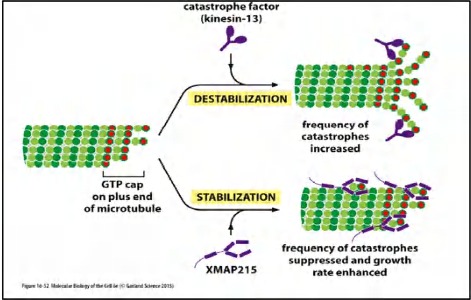

the microtubules of this interphase array are in a state of dynamic instability

individual microtubules are either growing or shrinking and stochastically switch between the two states. The switch from growth to shrinkage is called a catastrophe, and the switch from shrinkage to growth is called a rescue

The interphase array of few, long microtubules radiating from the single centrosome is converted to a larger number of shorter and more dynamic microtubules emanating (放射) from both centrosomes. During prophase, and particularly in prometaphase and metaphase (see Panel 17–1), the half-life of microtubules decreases dramatically.

Microtubule dynamics are controlled in the cell by a variety of regulatory proteins, including microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) that promote stability and catastrophe factors that destabilize microtubule plus ends

Many of these changes result from phosphorylation of specific proteins by M-Cdk and other mitotic protein kinases

Two mechanisms regulate microtubules dynamics:

- MAPs (Microtubule-associated proteins) stabilize arrays most of these factors are also regulated by phosphorylation (e.g., M-Cdk and other mitotic protein kinase)

- Catastrophe factors destabilize microtubule arrays

In mitosis, microtubule arrangement changes drastically and the microtubule instability increases greatly.

Microtubule array changes from “a few long” MTs in interphase into an array of “many short” MTs.

The balance between catastrophe factors and MAPs influences the length and the number of microtubules

Multiple Forces

The balance of opposing forces generated by different types of motor proteins determines the final length of the spindle.

- Dynein and kinesin-5 motors generally promote centrosome separation and increase spindle length.

- Kinesin-14 proteins do the opposite: they tend to pull the poles together

M-Cdk and other mitotic protein kinases are required for centrosome separation and maturation.

- M-Cdk and Aurora-A phosphorylate kinesin-5 motors and stimulate them to drive centrosome separation.

- Aurora-A and Plk also phosphorylate components of the centrosome and thereby promote its maturation.

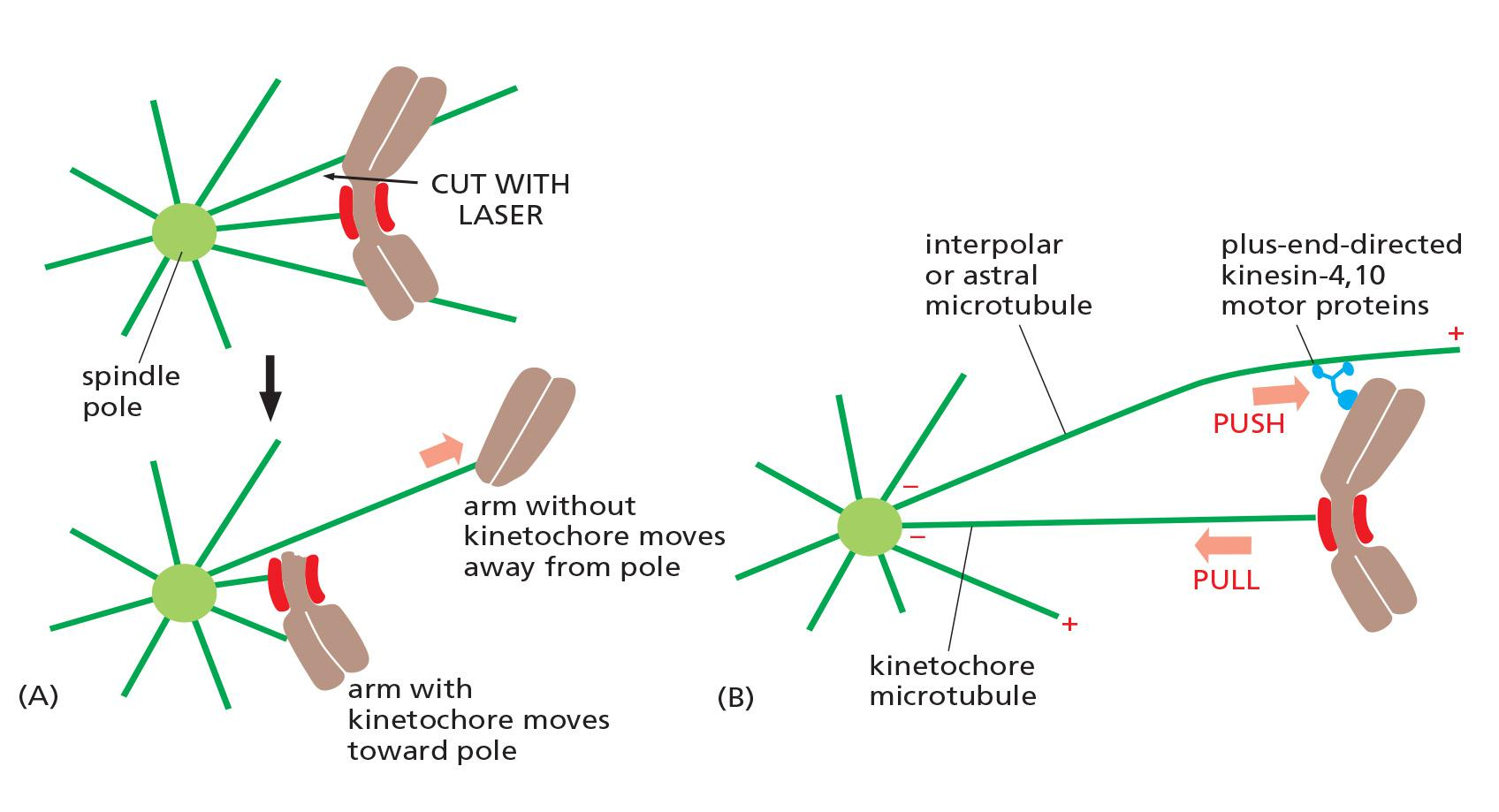

Multiple forces acts on chromosomes in the spindles

Three major spindle forces are particularly critical, although their strength and importance vary at different stages of mitosis.

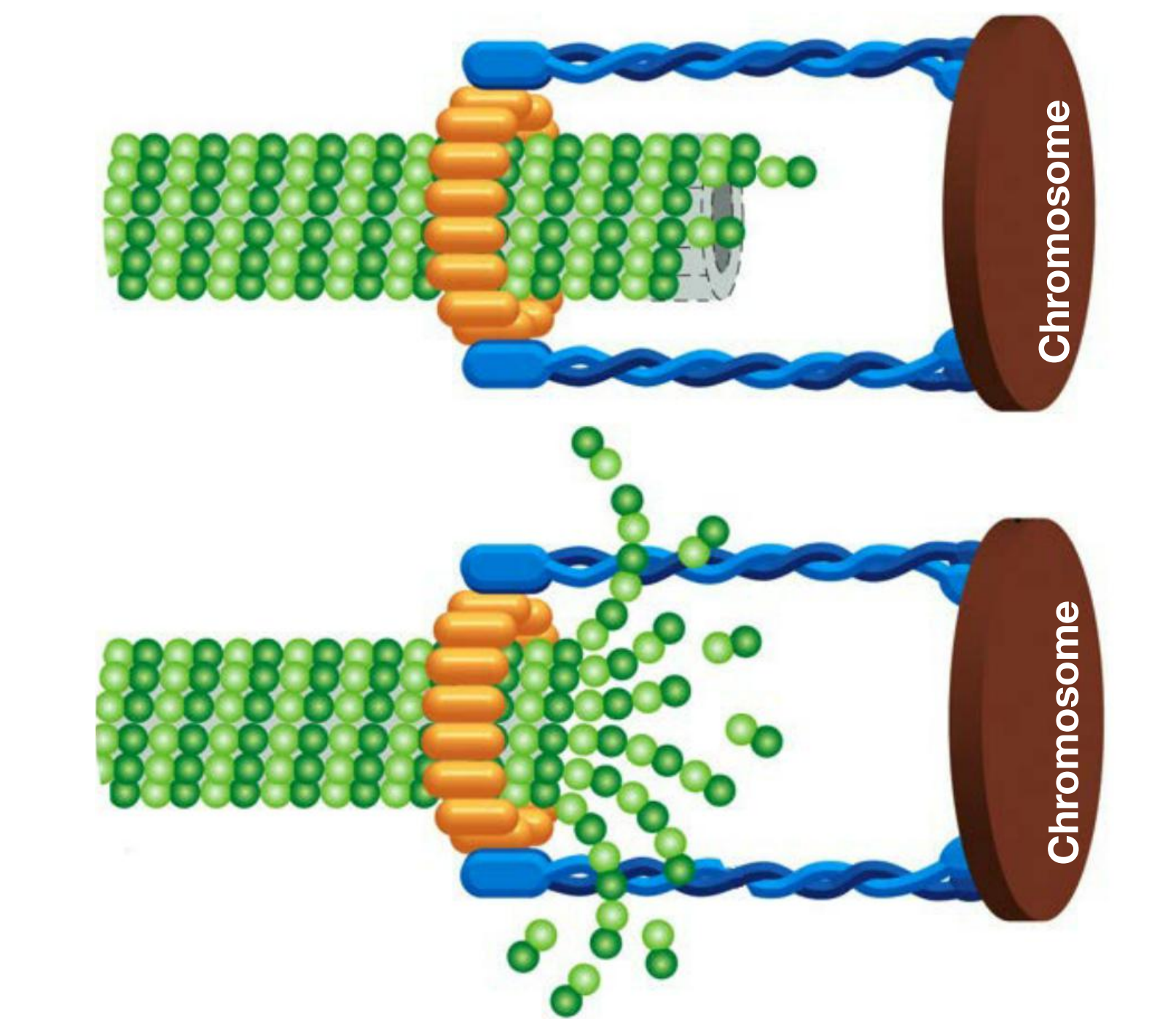

- The first major force pulls the kinetochore and its associated chromatid along the kinetochore microtubule toward the spindle pole. It is produced by proteins at the kinetochore itself

- this kinetochore-generated poleward force (极向力) does not require ATP or motor proteins.

- A second poleward force is provided in some cell types by microtubule flux, whereby the microtubules themselves are pulled toward the spindle poles and dismantled (拆开, 拆卸) at their minus ends

- flux also contributes to the poleward forces that move sister chromatids after they separate in anaphase.

- A third force acting on chromosomes is the polar ejection force (极射力), or polar wind.

- Plus-end directed kinesin-4 and 10 motors on chromosome arms interact with interpolar microtubules and transport the chromosomes away from the spindle poles

- This force is particularly important in prometaphase and metaphase, when it helps push chromosome arms out from the spindle.

the movements are seen to switch between two states—a poleward state, when the chromosomes are pulled toward the pole, and an away-from-the-pole, or neutral state, when the poleward forces are turned off and the polar ejection force pushes the chromosomes away

The switch between the two states may depend on the degree of tension in the kinetochore

- It has been proposed, for example, that, as chromosomes move toward a spindle pole, an increasing polar ejection force generates tension in the kinetochore nearest the pole, triggering a switch to the away-from-the-pole state and gradually resulting in the accumulation of chromosomes at the equator of the spindle.

- The force produced by proteins in kinetochore by an uncertain mechanism, which depends on microtubule depolymerization

- Microtubule flux; microtubules are pulled towards the spindle. Poles and dismantled at the minus end.

- Polar ejection force produced by plus-end kinesin (kinesin-4 and -10 motor). This is particularly important for aligning the chromosome at the metaphase plate.

Kinetochore complex captures microtubules and harnesses force of depolymerization:

Microtubule flux in the metaphase spindle:

forces may drive chromosome to the metaphase plate:

(2) Centrosomes

In most somatic animal cells, each spindle pole is focused at a protein organelle called the centrosome

- Each centrosome consists of a cloud of amorphous material(无定形材料) (called the pericentriolar matrix (中心粒基质)) that surrounds a pair of centrioles

The pericentriolar matrix nucleates a radial array of microtubules, with their fast-growing plus ends projecting outward and their minus ends associated with the centrosome.

The matrix contains a variety of proteins, including microtubule-dependent motor proteins, coiled-coil proteins that link the motors to the centrosome, structural proteins, and components of the cell-cycle control system. Most important, it contains γ-tubulin ring complexes

Centrosomes separate to set up spindle from opposite ends of cell

Centrosome Duplication Occurs Early in the Cell Cycle

Most animal cells contain a single centrosome that nucleates most of the cell’s cytoplasmic microtubules. The centrosome duplicates when the cell enters the cell cycle

- Centrosome duplication begins at about the same time as the cell enters S phase

- This centrosome pair remains together on one side of the nucleus until the cell enters mitosis.

Some cells—notably the cells of higher plants and the oocytes of many vertebrates—do not have centrosomes, and microtubule-dependent motor proteins and other proteins associate with microtubule minus ends to organize and focus the spindle poles

- 一些细胞(尤其是高等植物的细胞和许多脊椎动物的卵母细胞)没有中心体,微管依赖性运动蛋白和与微管负端相关的其他蛋白,从而组织并集中纺锤体极

Although the resulting acentrosomal spindle can segregate chromosomes normally, it lacks astral microtubules, which are responsible for positioning the spindle in animal cells; as a result, the spindle is often mispositioned in the cell.

M-Cdk promotes centrosome maturation: amount of γ-tubulin ring complex (γ-YuRC ) increases

- → more nucleating microtubules.

This first step in building the spindle is the separation of the centrosomes to opposite sides of the cell.

- M-Cdk (and other mitotic protein kinases e.g. Aurora-A kinase) promote centrosome separation.

(3) Kinesins and Dynein

Microtubule-Dependent Motor Proteins Govern Spindle Assembly and Function

The function of the mitotic spindle depends on numerous microtubule-dependent motor proteins

- these proteins belong to two families—the kinesin-related proteins, which usually move toward the plus end of microtubules, and dyneins, which move toward the minus end.

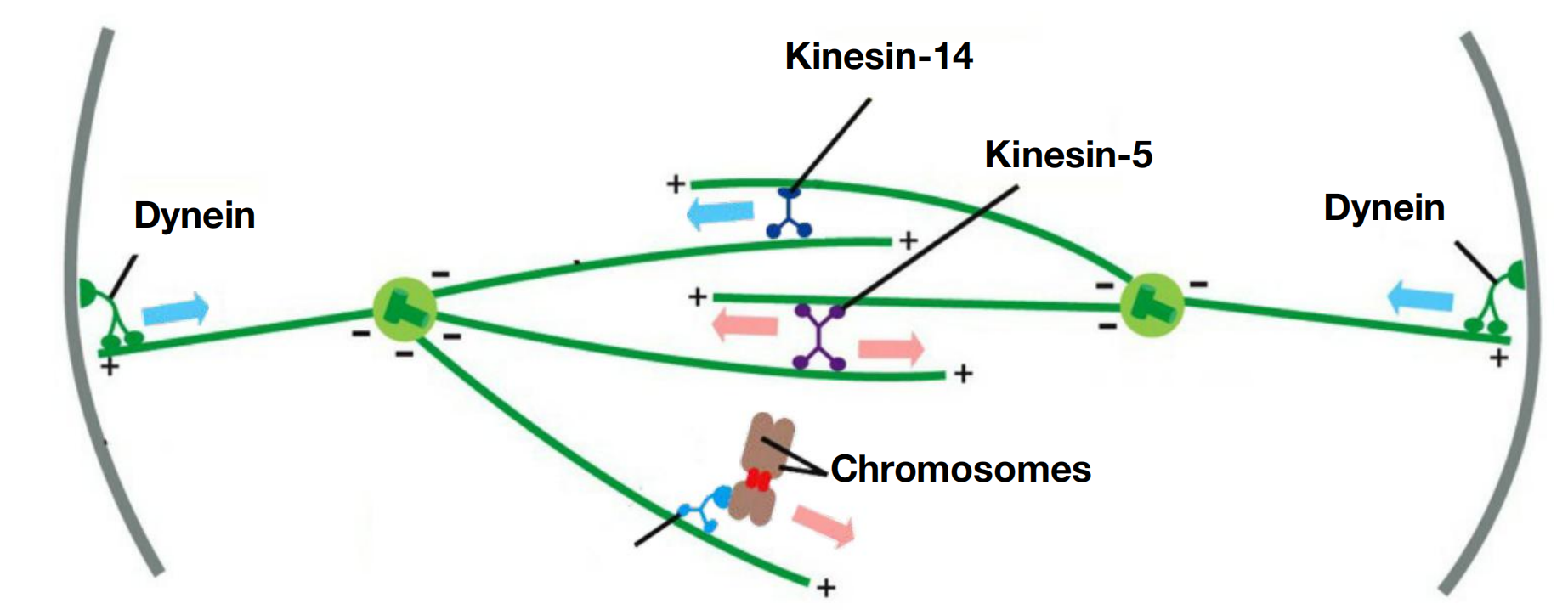

Four major types of motor proteins—kinesin-5, kinesin-14, kinesins-4/10, and dynein—are particularly important in spindle assembly and function

- Kinesin-5 proteins contain two motor domains that interact with the plus ends of antiparallel microtubules in the spindle midzone. Because the two motor domains move toward the plus ends of the microtubules, they slide the two antiparallel microtubules past each other toward the spindle poles, pushing the poles apart

- Kinesin-14 proteins, by contrast, are minus-end directed motors with a single motor domain and other domains that can interact with a neighboring microtubule. They can cross-link antiparallel interpolar microtubules at the spindle midzone and tend to pull the poles together

- Kinesin-4 and kinesin-10 proteins, also called chromokinesins, are plus-end directed motors that associate with chromosome arms and push the attached chromosome away from the pole (or the pole away from the chromosome)

- Dyneins are minus-end directed motors that, together with associated proteins, organize microtubules at various locations in the cell. They link the plus ends of astral microtubules to components of the actin cytoskeleton at the cell cortex,

- for example; by moving toward the minus end of the microtubules, the dynein motors pull the spindle poles toward the cell cortex and away from each other.

Kinesins and dynein help assemble and position the spindle

Molecular motor proteins, kinesins and dynein, push and pull the centrosomes to position them.

- kinesin-5: pushes centrosomes away from each other

- dynein: pulls centrosomes towards the PM (away from each other)

- kinesin-14 : pull centrosomes together

(4) bipolar spindle assembly

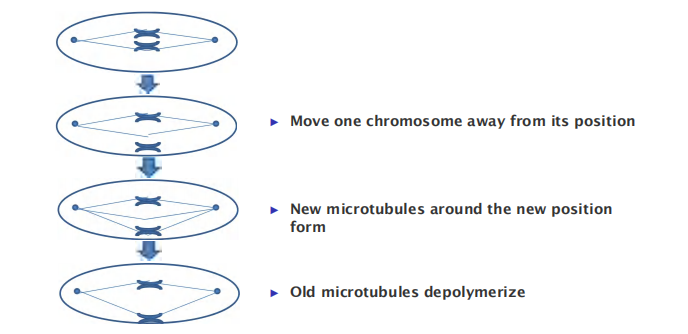

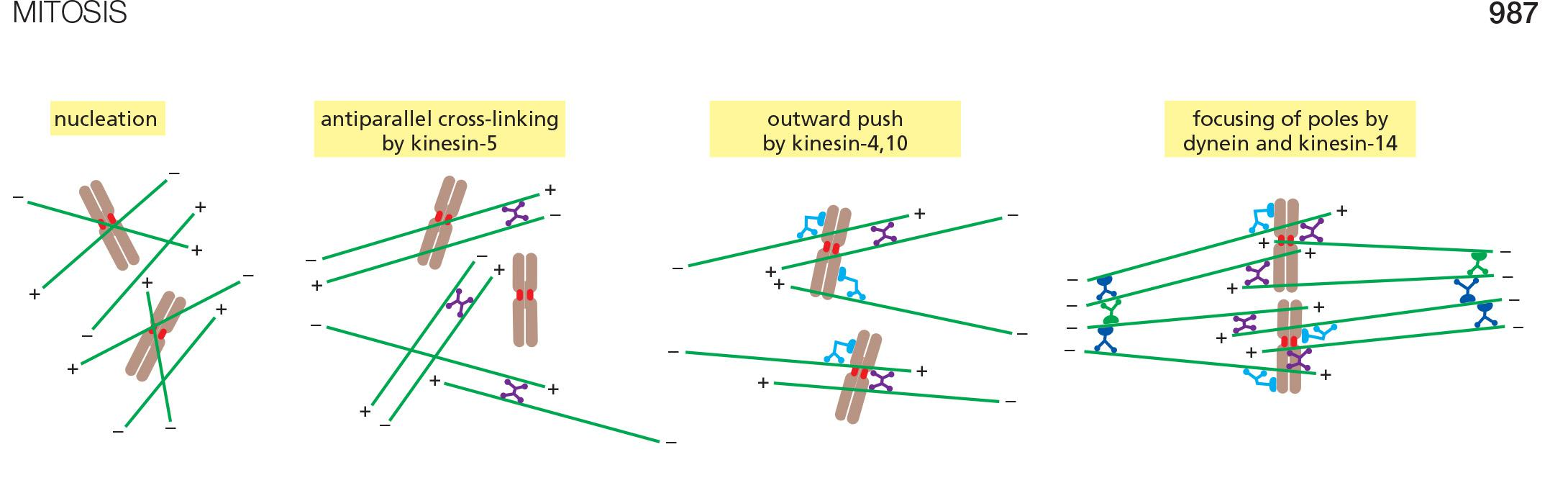

Mitotic Chromosomes Promote Bipolar Spindle Assembly

By creating a local environment that favors both microtubule nucleation and microtubule stabilization, they play an active part in spindle formation.

- Move one chromosome away from its position

- New microtubules around the new position form

- Old microtubules depolymerize

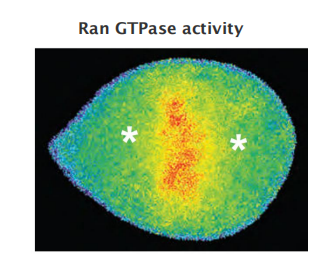

Ran

Mitotic chromosome-promoted bipolar spindle assembly via Ran GTPase

Chromosome-bound GEF activates Ran-GTP:

- Ran-GTP releases microtubule-stabilizing proteins

- Ran-GTP stimulates local nucleation and stabilizes microtubules around chromosomes

Acentrosomal spindle assembly

Kinesin-5 cross-links microtubules and pushes minus ends towards the spindle poles (in opposite directions)

Kinesins-4 and -10 push the minus ends away from the chromosomes

Dynein and Kinesin-14 cross-link and focus minus ends to form two spindle poles

The acentrosomal spindle assembly:

- Exists in higher plants

- Exists in many animal oocytes

- Certain insect embryos without fertilization (remember: centrosomes are provided by the sperm cell)

- However in animal cells, acentrosomal spindle is often mis-positioned and results in abnormalities in cytokinesis

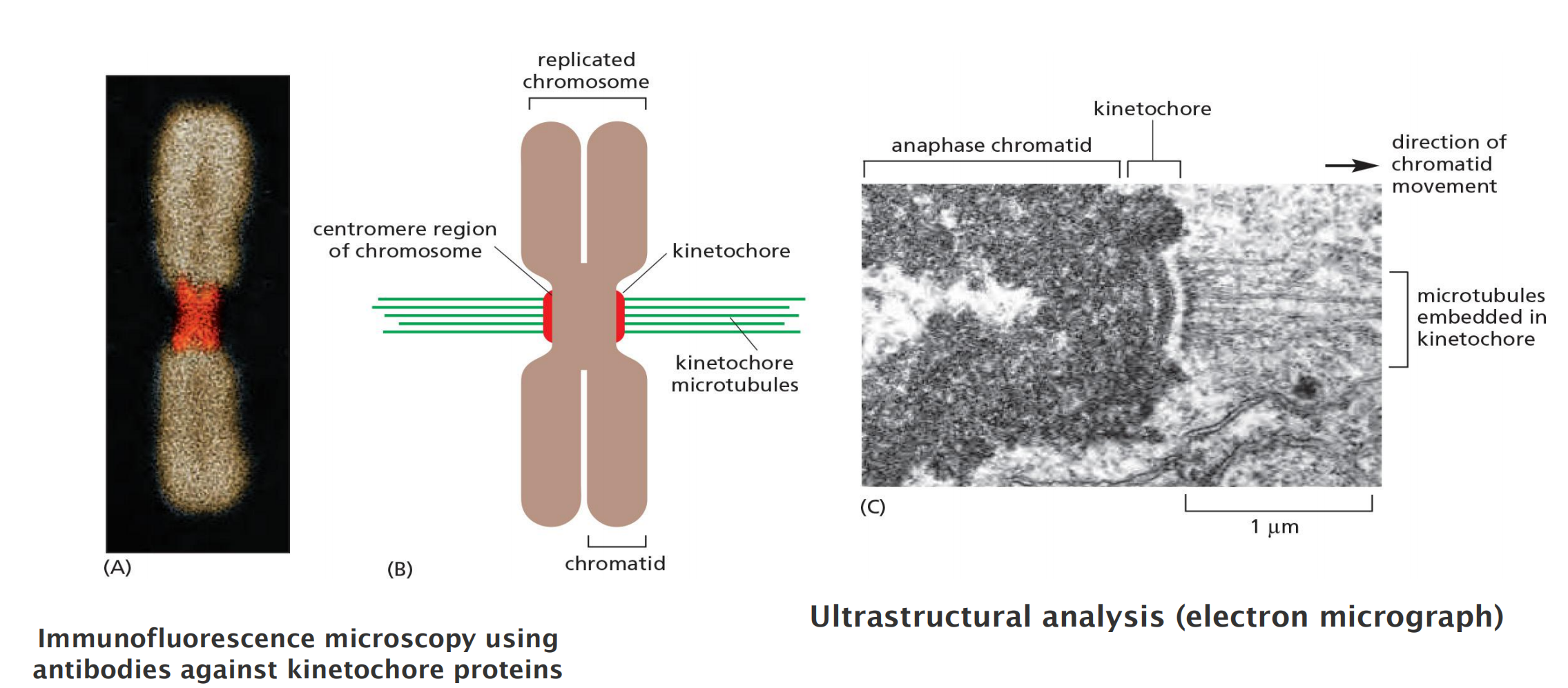

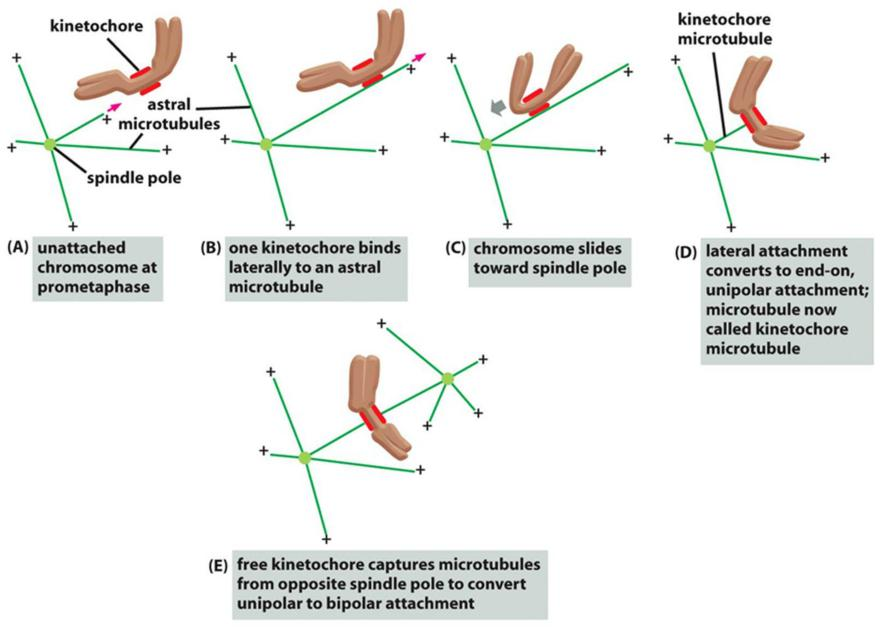

(5) Kinetochore

Kinetochores Attach Sister Chromatids to the Spindle

Spindle microtubules become attached to each chromatid at its kinetochore, a giant, multilayered protein structure that is built at the centromeric region of the chromatid

Regulation of plus-end polymerization and depolymerization at the kinetochore is critical for the control of chromosome movement on the spindle,

Careful microscopic analysis suggests that short microtubules in the vicinity of the chromosomes become embedded in the plus-end-binding sites of the kinetochore. Polymerization at these plus ends then results in growth of the microtubules away from the kinetochore. The minus ends of these kinetochore microtubules are eventually cross-linked to other minus ends and focused by motor proteins at the spindle pole

Kinetochore attach sister chromatids to the spindle

Kinetochore: a multilayer protein structure that is built on the heterochromatin in the centromere

The capture of centrosome microtubules by kinetochores (trial & error)

Three steps to success:

- Firstly, short microtubules close to chromosomes interact with kinetochores

- Secondly, growth of the embedded plus ends result in growth of the microtubules away from the kinetochore.

- Thirdly, motor proteins crosslinks and focus the minus ends in the spindle poles.

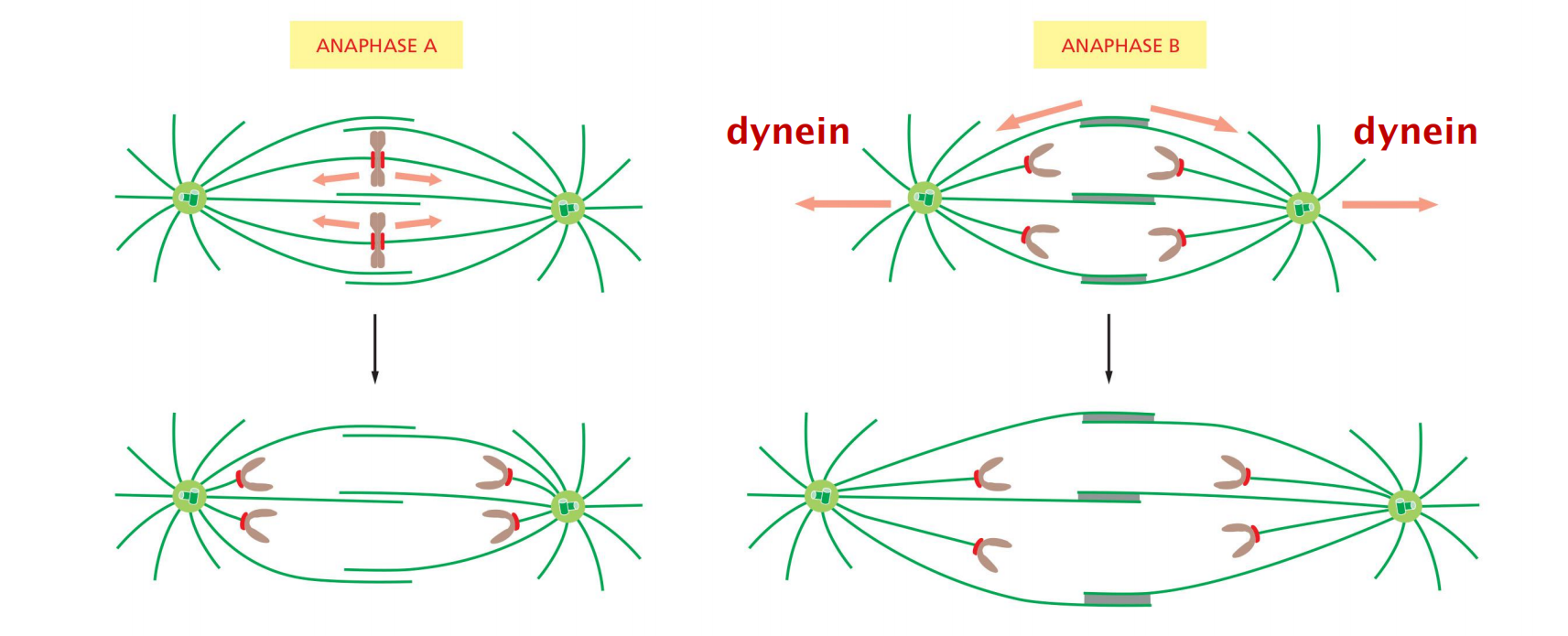

(6) Anaphase A and Anaphase B

Chromosomes Segregate in Anaphase A and B

The sudden loss of sister-chromatid cohesion at the onset of anaphase leads to sister-chromatid separation, which allows the forces of the mitotic spindle to pull the sisters to opposite poles of the cell—called chromosome segregation

The chromosomes move by two independent and overlapping processes

- The first, anaphase A, is the initial poleward movement of the chromosomes, which is accompanied by shortening of the kinetochore microtubules

- The second, anaphase B, is the separation of the spindle poles themselves, which begins after the sister chromatids have separated and the daughter chromosomes have moved some distance apart

Chromosome movement in anaphase A depends on a combination of the two major poleward forces described earlier. The first is the force generated by microtubule depolymerization at the kinetochore, which results in the loss of tubulin subunits at the plus end as the kinetochore moves toward the poles

The second is provided by microtubule flux, which is the poleward movement of the microtubules toward the spindle pole, where minus-end depolymerization occurs.

- The relative importance of these two forces during anaphase varies in different cell types: in embryonic cells, chromosome movement depends mainly on microtubule flux, for example, whereas movement in yeast and vertebrate somatic cells results primarily from forces generated at the kinetochore.

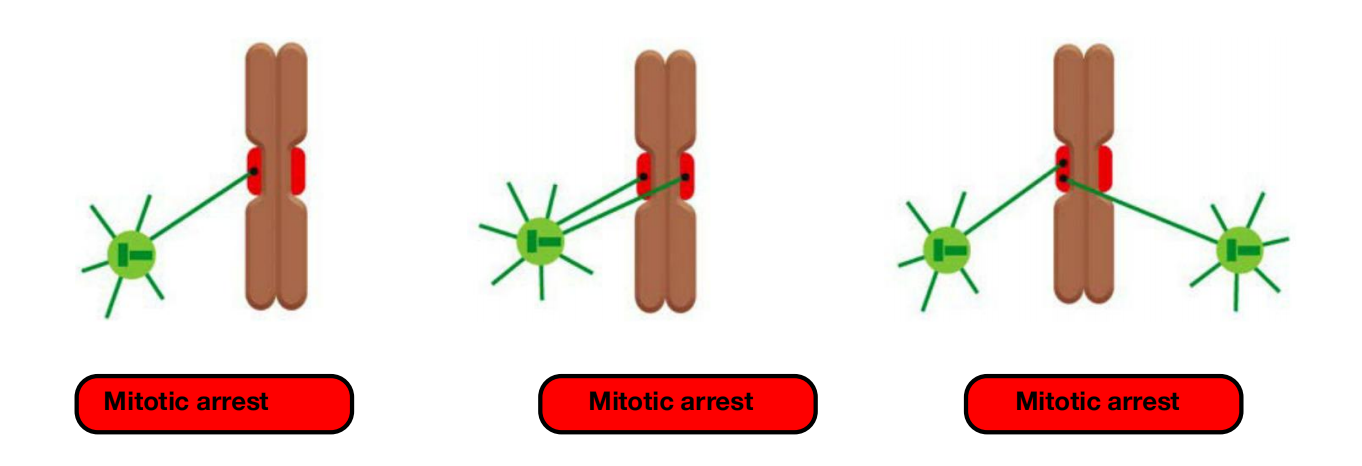

Unattached or incorrectly attached chromosomes results in mitotic arrest

(7) Eliminate Errors

- eliminate errors in kinetochore attachment in the sister chromatids

Incorrect attachments are corrected by a system of trial and error

- incorrect attachments are highly unstable and do not last, whereas correct attachments become locked in place.

When chromosomes are incorrectly attached—when both sister chromatids are attached to the same spindle pole, for example—tension is low and the kinetochore sends an inhibitory signal that loosens the grip of its microtubule attachment site, allowing detachment to occur.

- When bi-orientation occurs, the high tension at the kinetochore shuts off the inhibitory signal, strengthening microtubule attachment. In animal cells, tension not only increases the affinity of the attachment site but also leads to the attachment of additional microtubules to the kinetochore

- This results in the formation of a thick kinetochore fiber composed of multiple microtubules.

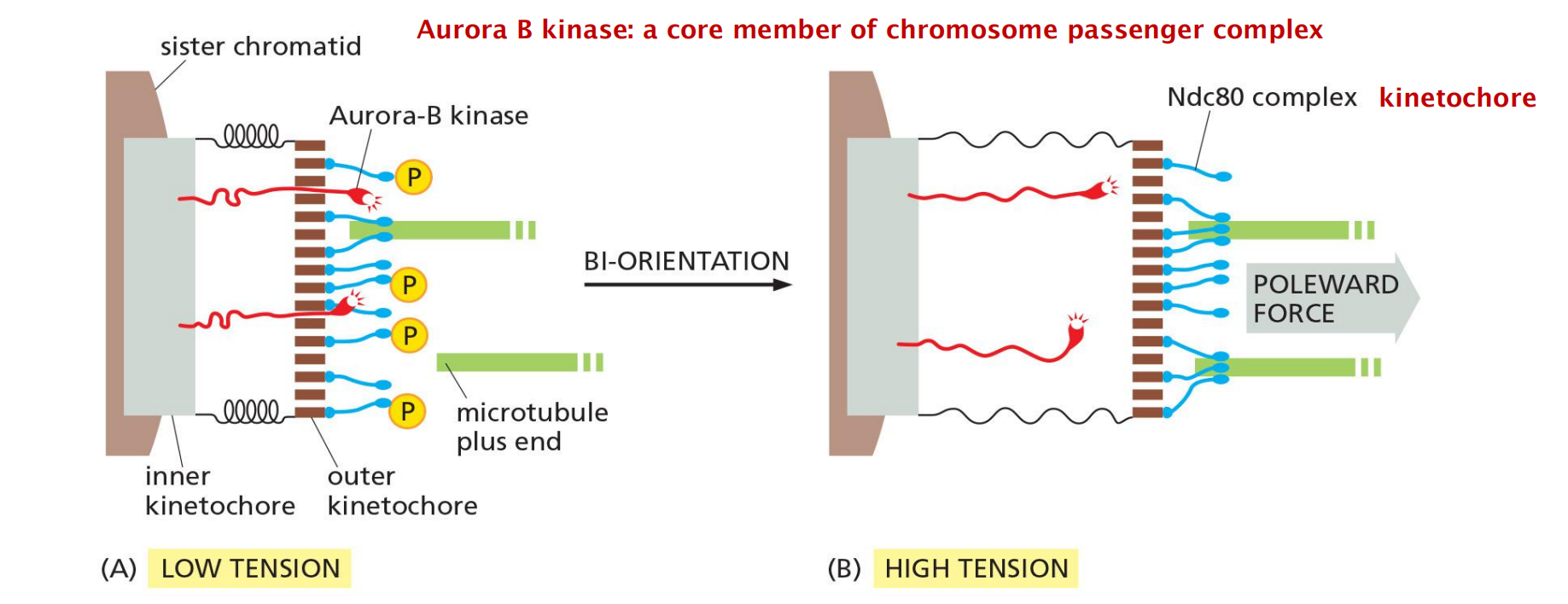

The tension-sensing mechanism depends on the protein kinase Aurora-B, which is associated with the kinetochore and is thought to generate the inhibitory signal that reduces the strength of microtubule attachment in the absence of tension.

- It phosphorylates several components of the microtubule attachment site, including the Ndc80 complex, decreasing the site’s affinity for a microtubule plus end.

- When bi-orientation occurs, the resulting tension somehow reduces phosphorylation by Aurora-B, thereby increasing the affinity of the attachment site

This tension sensing mechanism is the checkpoint for the successful metaphase to anaphase transition!!!

A tension sensing mechanisms through protein kinase Aurora B

Incorrect attachments are corrected by a system of trial and error that is based on a simple principle:

- incorrect attachments are highly unstable and do not last, whereas

- correct attachments become locked in place.

- Unattached chromosomes prevent activation of anaphase promoting complex

Triggers into Anaphase

(1) Chromosome Attachment

Chromosome attachment to microtubules from both centrosomes triggers anaphase

All these activities reach a balance that determines the final length of spindles.

- →mechano-sensing? (Aurora B kinase or undiscovered lands?)

(2) Activation of APC/C

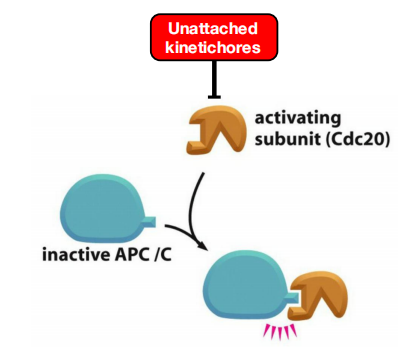

The APC/C Triggers Sister-Chromatid Separation and the Completion of Mitosis

Although M-Cdk activity sets the stage for this event, the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) discussed earlier throws the switch that initiates sister-chromatid separation by ubiquitylating several mitotic regulatory proteins and thereby triggering their destruction

During metaphase, cohesins holding the sister chromatids together resist the poleward forces that pull the sister chromatids apart. Anaphase begins with the sudden loss of sister-chromatid cohesion, which allows the sisters to separate and move to opposite poles of the spindle

- The APC/C initiates the process by targeting the inhibitory protein securin for destruction

Before anaphase, securin binds to and inhibits the activity of a protease called separase

- The destruction of securin at the end of metaphase releases separase, which is then free to cleave one of the subunits of cohesin.

In addition to securin, the APC/C also targets the S- and M-cyclins for destruction, leading to the loss of most Cdk activity in anaphase.

- Cdk inactivation allows phosphatases to dephosphorylate the many Cdk target substrates in the cell, as required for the completion of mitosis and cytokinesis.

what activates the APC/C?

APC/C activation requires binding to the protein Cdc20, At least two processes regulate Cdc20 and its association with the APC/C.

- First, Cdc20 synthesis increases as the cell approaches mitosis, owing to an increase in the transcription of its gene.

- Second, phosphorylation of the APC/C helps Cdc20 bind to the APC/C, thereby helping to create an active complex. Among the kinases that phosphorylate and thus activate the APC/C is M-Cdk.

Thus, M-Cdk not only triggers the early mitotic events leading up to metaphase, but it also sets the stage for progression into anaphase.

The ability of M-Cdk to promote Cdc20–APC/C activity creates a negative feedback loop: M-Cdk sets in motion a regulatory process that leads to cyclin destruction and thus its own inactivation.

Activation of APC/C triggers entry into anaphase and separation of chromosomes

Anaphase promoting complex is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets mitotic proteins for degradation

- APC/C is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that marks the S/M-cyclins for degradation by the 26S proteasome

APC/C degrades securing which triggers degradation of cohesins to allow chromosomes to separate

- APC/C activates the separase by poly-ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of securin (release of separase).

- Separase cleaves cohesins on sister chromatids.

- Degrade S-cyclin and M-cyclins.

Unattached Chromosomes Block Sister-Chromatid Separation: The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint

Drugs that destabilize microtubules, such as colchicine or vinblastine (discussed in Chapter 16), arrest cells in mitosis for hours or even days.

The checkpoint mechanism ensures that cells do not enter anaphase until all chromosomes are correctly bi-oriented on the mitotic spindle.

- The spindle assembly checkpoint depends on a sensor mechanism that monitors the strength of microtubule attachment at the kinetochore, possibly by sensing tension as described earlier

- Any kinetochore that is not properly attached to the spindle sends out a diffusible negative signal that blocks Cdc20–APC/C activation throughout the cell and thus blocks the metaphase-to-anaphase transition

The negative checkpoint signal depends on several proteins, including Mad2, which are recruited to unattached kinetochores

- Detailed structural analyses of Mad2 suggest that the unattached kinetochore acts like an enzyme that catalyzes a change in the conformation of Mad2, so that Mad2, together with other proteins, can bind and inhibit Cdc20–APC/C.

In mammalian somatic cells, the spindle assembly checkpoint determines the normal timing of anaphase

5. Telophase

Segregated Chromosomes Are Packaged in Daughter Nuclei at Telophase

In telophase, the final stage of mitosis, the two sets of chromosomes are packaged into a pair of daughter nuclei. The first major event of telophase is the disassembly of the mitotic spindle, followed by the re-formation of the nuclear envelope.

Nuclear pore complexes are incorporated into the envelope, the nuclear lamina re-forms, and the envelope once again becomes continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum.

We saw earlier that phosphorylation of various proteins by M-Cdk promotes spindle assembly, chromosome condensation, and nuclear-envelope breakdown in early mitosis.

- phosphorylation of various proteins by M-Cdk promotes spindle assembly, chromosome condensation, and nuclear-envelope breakdown in early mitosis. It is thus not surprising that the dephosphorylation of these same proteins is required for spindle disassembly and the re-formation of daughter nuclei in telophase

- In budding yeast, for example, the completion of mitosis depends on the activation of a phosphatase called Cdc14, which dephosphorylates a subset of Cdk substrates involved in anaphase and telophase.

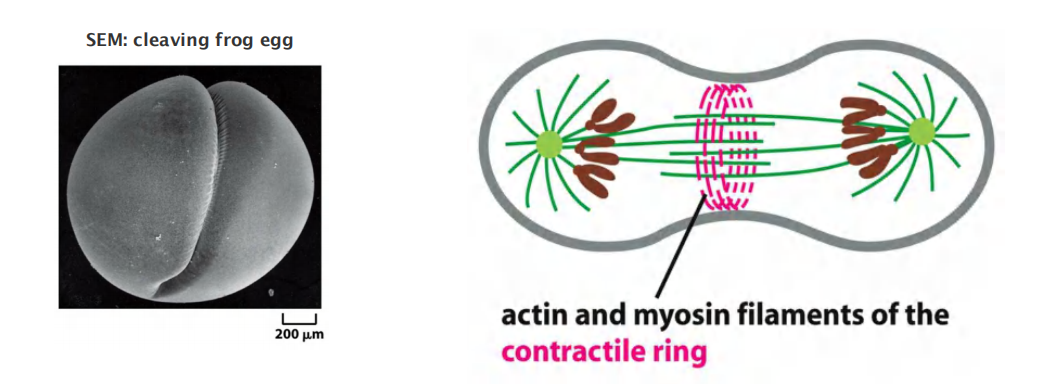

Cytokinesis

(Cytokinesis: producing two cells)

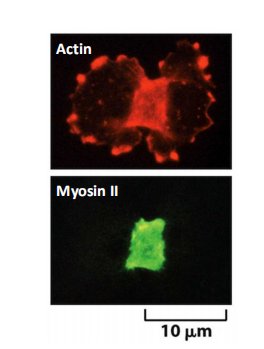

1. Actin-myosin filament rings Assemble

The first visible change of cytokinesis in an animal cell is the sudden appearance of a pucker, or cleavage furrow, on the cell surface

The furrow rapidly deepens and spreads around the cell until it completely divides the cell in two.

- The structure underlying this process is the contractile ring—a dynamic assembly composed of actin filaments, myosin II filaments, and many structural and regulatory proteins

Actin-myosin filament rings assemble at the midpoint of a dividing cell

Actin and Myosin II in the Contractile Ring Generate the Force for Cytokinesis

In interphase cells, actin and myosin II filaments form a cortical network underlying the plasma membrane. In some cells, they also form large cytoplasmic bundles called stress fibers

As cells enter mitosis, these arrays of actin and myosin disassemble; much of the actin reorganizes, and myosin II filaments are released.

As the sister chromatids separate in anaphase, actin and myosin II begin to accumulate in the rapidly assembling contractile ring

- Assembly of the contractile ring results in part from the local formation of new actin filaments, which depends on formin proteins that nucleate the assembly of parallel arrays of linear, unbranched actin filaments

After anaphase, the overlapping arrays of actin and myosin II filaments contract to generate the force that divides the cytoplasm in two

- unlike actin in muscle, the actin filaments in the ring are highly dynamic, and their arrangement changes continually during cytokinesis.

The contractile ring is finally dispensed with altogether when cleavage ends, as the plasma membrane of the cleavage furrow narrows to form the midbody.

- The midbody persists as a tether between the two daughter cells and contains the remains of the central spindle, a large protein structure derived from the antiparallel interpolar microtubules of the spindle midzone, packed tightly together within a dense matrix material

Force of myosin filaments constricts cell at midpoint

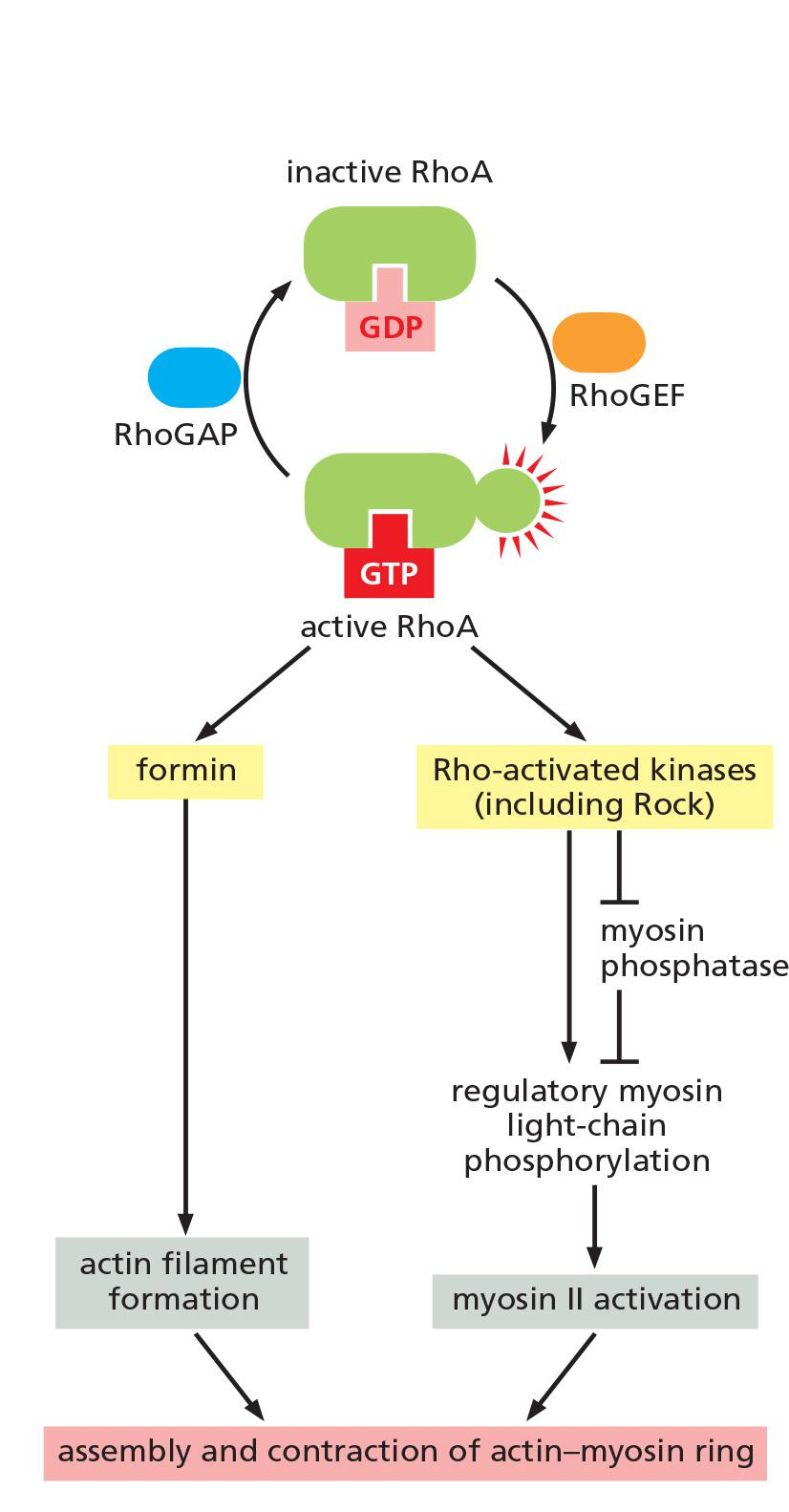

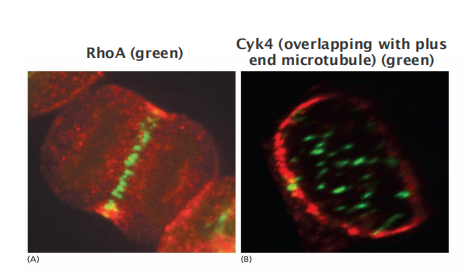

RhoA

Local Activation of RhoA Triggers Assembly and Contraction of the Contractile Ring

RhoA, a small GTPase of the Ras superfamily (see Table 15–5), controls the assembly and function of the contractile ring at the site of cleavage.

RhoA is activated at the cell cortex at the future division site, where it promotes actin filament formation, myosin II assembly, and ring contraction.

- It stimulates actin filament formation by activating formins, and it promotes myosin II assembly and contractions by activating multiple protein kinases, including the Rho-activated kinase Rock

RhoA is thought to be activated by a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Rho-GEF), which is found at the cell cortex at the future division site and stimulates the release of GDP and binding of GTP to RhoA

Small GTPase RhoA regulate formation of the contractile ring

Actin filament formation and myosin II assembly and ring contraction is promoted by the Ras GTPase RhoA

- RhoA is activated by a GEF at the cell cortex

- RhoA-GTP activates formin which assembles actin filaments

- RhoA-GTP activates Rho-activated kinase (Rock)

- Rock activates the regulatory myosin light chains (RMLCs), triggering contraction.

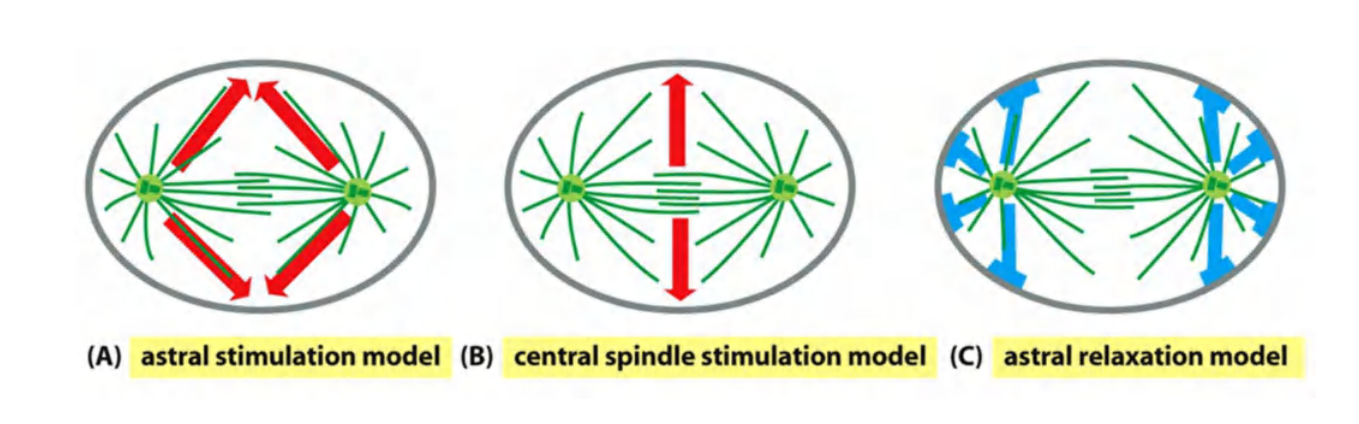

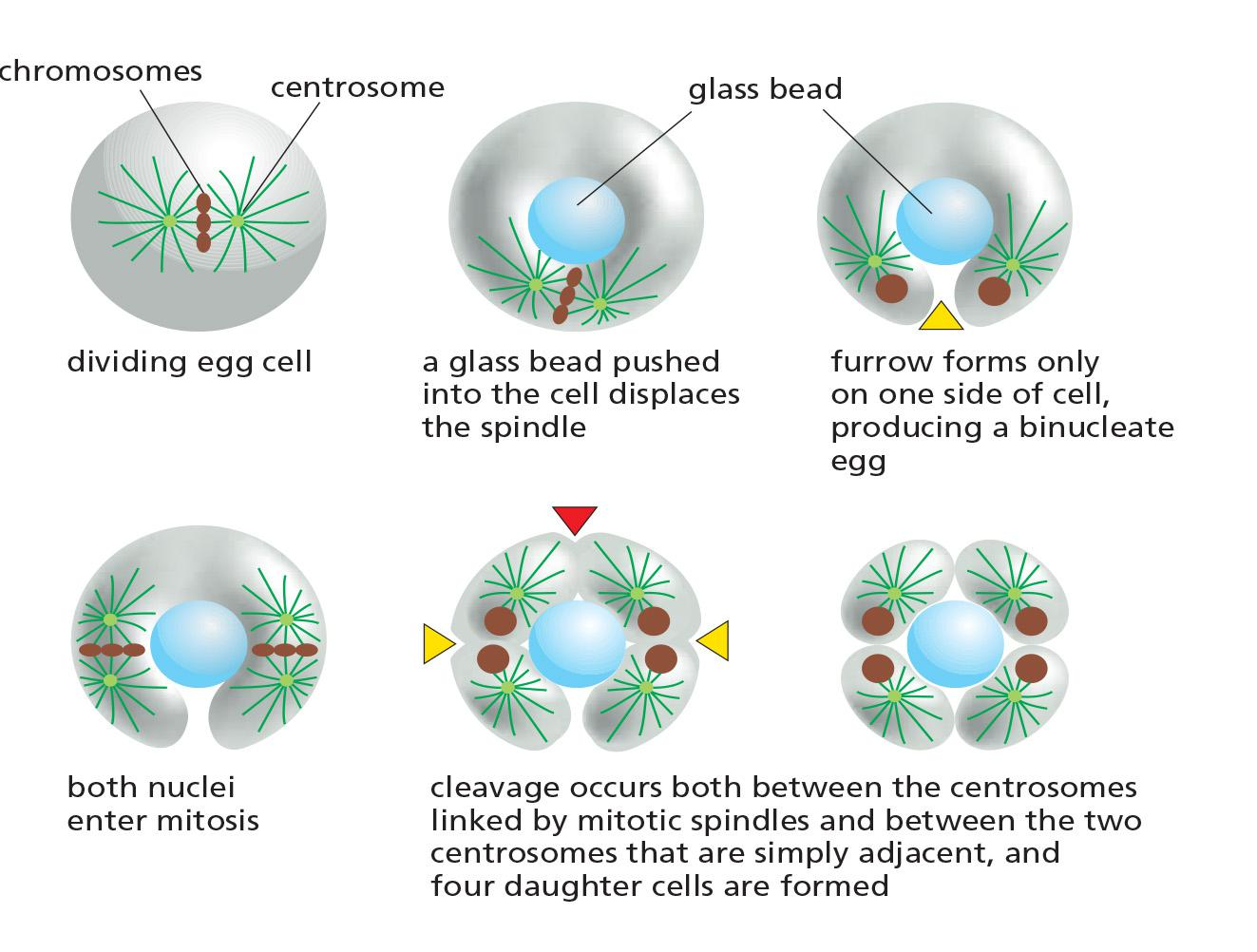

Spindles determine the position of the cleavage furrow

The Microtubules of the Mitotic Spindle Determine the Plane of Animal Cell Division

The correct timing and positioning of cytokinesis in animal cells are achieved by mechanisms that depend on the mitotic spindle.

Cytokinesis also occurs at the correct time because dephosphorylation of Cdk substrates, which depends on cyclin destruction in metaphase and anaphase, initiates cytokinesis.

supporting the idea that signals generated by the spindle induce local furrow formation.

How does the mitotic spindle specify the site of division? Three general mechanisms have been proposed:

- The first is termed the astral stimulation model, in which the astral microtubules carry furrow-inducing signals, which are somehow focused in a ring on the cell cortex, halfway between the spindle poles.

- A second possibility, called the central spindle stimulation model, is that the spindle midzone, or central spindle, generates a furrow-inducing signal that specifies the site of furrow formation at the cell cortex

- The overlapping interpolar microtubules of the central spindle associate with numerous signaling proteins, including proteins that may stimulate RhoA

- A third model proposes that, in some cell types, the astral microtubules promote the local relaxation of actin–myosin bundles at the cell cortex. According to this astral relaxation model, the cortical relaxation is minimal at the spindle equator, thus promoting cortical contraction at that site

Three models have been proposed, but no agreement yet…

In some cell types, the site of ring assembly is chosen before mitosis. In budding yeasts, for example, a ring of proteins called septins assembles in late G

1at the future division site.

- The septins are thought to form a scaffold onto which other components of the contractile ring, including myosin II, assembles

- In plant cells, an organized band of microtubules and actin filaments, called the preprophase band, assembles just before mitosis and marks the site where the cell wall will assemble and divide the cell in two

Localization of cytokinesis regulators at the central spindle

- Cyk4 and RhoA

Influence of aster microtubule on the cleavage plane

The Phragmoplast Guides Cytokinesis in Higher Plants

In most animal cells, the inward movement of the cleavage furrow depends on an increase in the surface area of the plasma membrane.

Membrane deposition is particularly important for cytokinesis in higher-plant cells

- These cells are enclosed by a semirigid cell wall

- Rather than a contractile ring dividing the cytoplasm from the outside in, the cytoplasm of the plant cell is partitioned from the inside out by the construction of a new cell wall, called the cell plate, between the two daughter nuclei

The assembly of the cell plate begins in late anaphase and is guided by a structure called the phragmoplast (成膜体), which contains microtubules derived from the mitotic spindles

Motor proteins transport small vesicles along these microtubules from the Golgi apparatus to the cell center.

- These vesicles, filled with polysaccharide and glycoproteins required for the synthesis of the new cell wall, fuse to form a disc-like, membrane-enclosed structure called the early cell plate

2. Stages of Cytokinesis

Four stages of cytokinesis

- initiation: contractile ring formation

- contraction: myosin II/actin contraction

- membrane insertion: plasma membrane addition

- completion

3. Organelle division / distribution

Membrane-Enclosed Organelles Must Be Distributed to Daughter Cells During Cytokinesis

Organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts are usually present in large enough numbers to be safely inherited if, on average, their numbers roughly double once each cycle.

The ER in interphase cells is continuous with the nuclear membrane and is organized by the microtubule cytoskeleton

In most cells, the ER remains largely intact and is cut in two during cytokinesis. The Golgi apparatus is reorganized and fragmented during mitosis. Golgi fragments associate with the spindle poles and are thereby distributed to opposite ends of the spindle

Organelle grow from pre-existing organelle and double in cell cycle.

Mitochondria

- Mitochondria and plastids (e.g. chloroplasts) double and divide in each cell cycle

ER

- ER remain intact, organized by microtubule, and “cut” into two halves in cytokinesis.

Golgi

- Golgi apparatus fragmented and reorganized.

- The Golgi apparatus is associated with the spindle poles

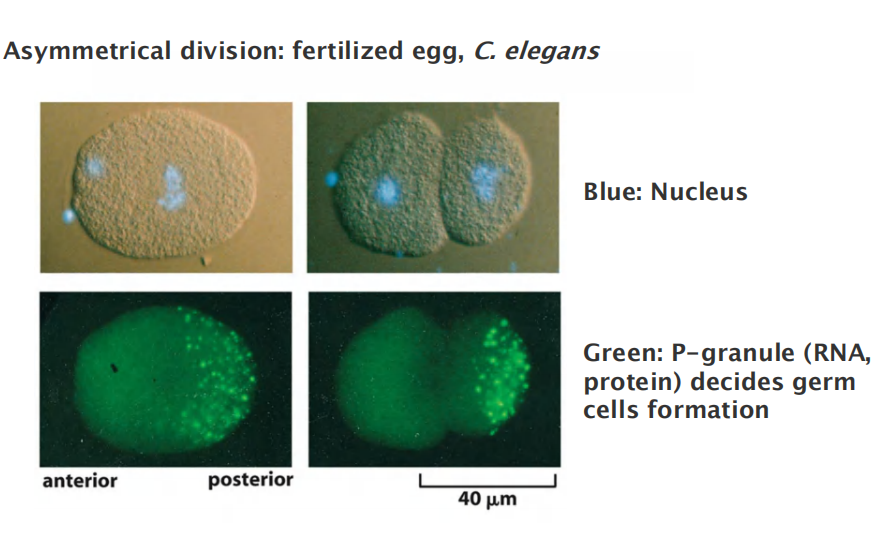

4. Symmetrical and asymmetrical division

Some Cells Reposition Their Spindle to Divide Asymmetrically

Astral microtubules and motor proteins that either push or pull on these microtubules contribute to the centering process.

It seems likely that changes in local regions of the cell cortex direct such spindle movements and that motor proteins localized there pull one of the spindle poles, via its astral microtubules, to the appropriate region.

Most divisions are symmetrical

During development, asymmetrical division is typically associated with different fate in cell development, the spindle positioning is important and nicely controlled

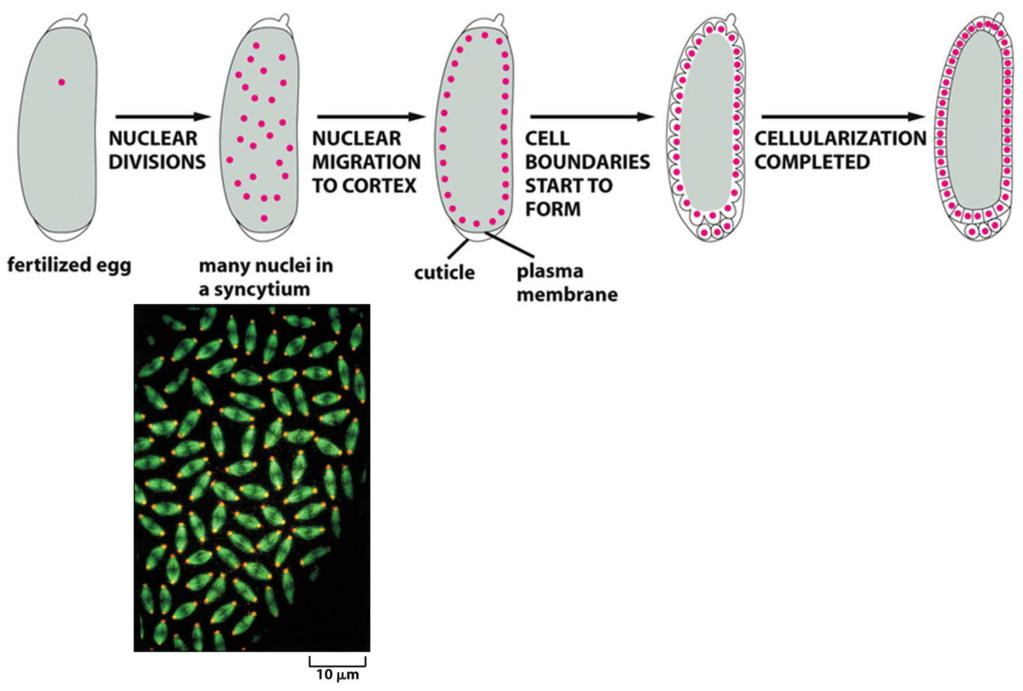

5. Mitosis without cytokinesis

A cell in which multiple nuclei share the same cytoplasm is called a syncytium (多核体;含胞体). This arrangement greatly speeds up early development,

After these rapid nuclear divisions, membranes are created around each nucleus in one round of coordinated cytokinesis called cellularization.

Happens in:

- Drosophila embryo

- Megakaryotcytes (blood platelets)

- Hepatocytes

- Heart muscle cell

Mitosis without cytokinesis: Drosophila embryo

Syncytium and cellularization for Drosophila embryo

6. The G1 Phase Is a Stable State of Cdk Inactivity

A key regulatory event in late M phase is the inactivation of Cdks, which is driven primarily by APC/C-dependent cyclin destruction. As described earlier, the inactivation of Cdks in late M phase has many functions: it triggers the events of late mitosis, promotes cytokinesis, and enables the synthesis of prereplicative complexes at DNA replication origins.

In most cells, this state of Cdk inactivity generates a G1 gap phase, during which the cell grows and monitors its environment before committing to a new cell cycle.

In early animal embryos, the inactivation of M-Cdk in late mitosis is due almost entirely to the action of Cdc20–APC/C, discussed earlier.

Cdh1–APC/C activation, CKI accumulation, and decreased cyclin gene expression act together to ensure that the early G1 phase is a time when essentially all Cdk activity is suppressed.