L5 Audition and Language

Learning Objectives

Part1:

- Describe the parts of the ear and the auditory pathway

- Describe the detection of pitch, timbre, and the location of the source of a sound.

- Describe the structures and functions of the vestibular system.

Part2:

- Describe Broca’s aphasia (失语症) and the three major speech deficits that result from damage to Broca’s area: agrammatism, anomia, and articulation difficulties

- Describe the symptoms of Wernicke’s aphasia, pure word deafness, and transcortical sensory aphasia and explain how they are related

- Discuss the brain mechanisms that underlie our ability to understand the meanings of words and to express our own thoughts and perceptions in words.

- Describe the symptoms of conduction aphasia and anomic aphasia and the brain damage that produces them.

- Discuss research on aphasia in deaf people.

- Discuss research on the brain mechanisms of prosody(韵律)—the use of rhythm and emphasis in speech—and stuttering.

- Describe pure alexia(失读症) and explain why this disorder is caused by damage to two specific parts of the brain.

- Describe whole-word and phonetic reading and discuss three acquired dyslexias(诵读困难): surface dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, and direct dyslexia.

- Explain the relationship between speaking and writing and describe the symptoms of phonological dysgraphia (书写困难), orthographic dysgraphia, and semantic (direct) dysgraphia.

- Describe research on the neurological basis of developmental dyslexias.

一、Audition

The Stimulus

We hear sounds, which are produced by objects that vibrate and set molecules of air into motion

When an object vibrates, its movements cause molecules of air surrounding it alternately to condense and rarefy (pull apart), producing waves that travel away from the object at approximately 761 miles per hour (340 meter per sec).

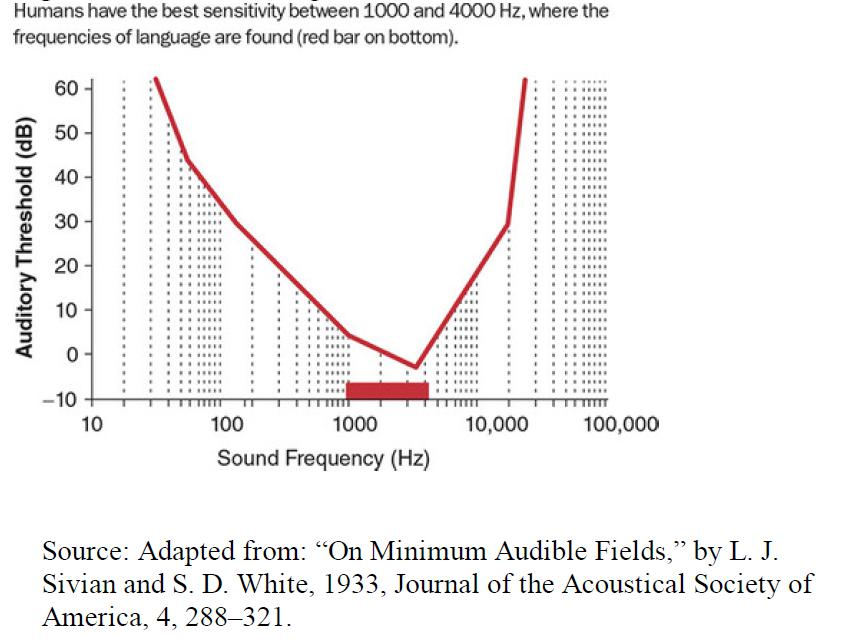

If the vibration ranges between approximately 30 and 20,000 times per second, these waves will stimulate receptor cells in our ears and will be perceived as sounds

- Changes in air pressure from sound waves move the eardrum in and out. Air molecules are closer together in regions of higher pressure and farther apart in regions of lower pressure.

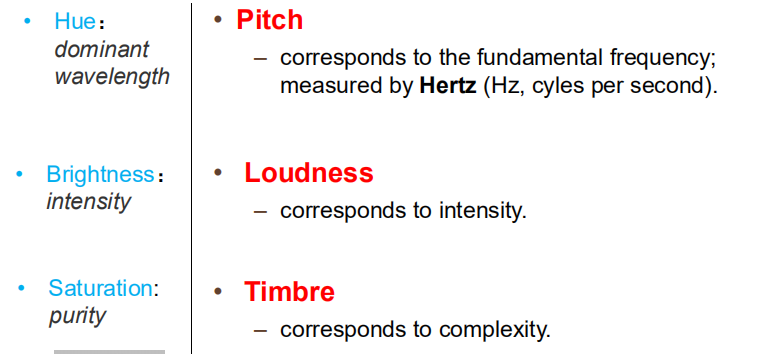

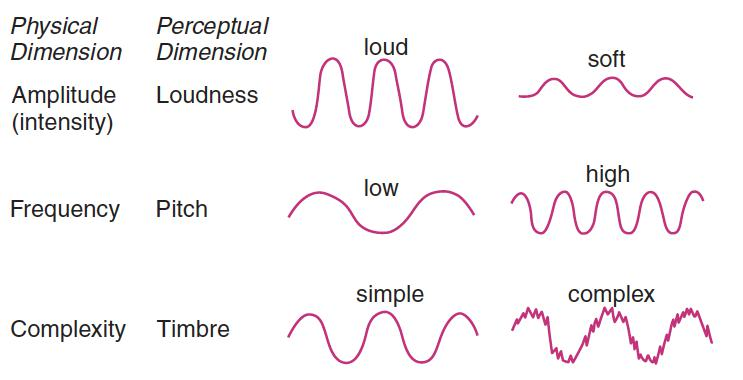

Three perceptual dimensions of color and sound:

- Pitch: corresponds to the fundamental frequency; measured by Hertz (Hz, cyles per second).

- **Loudness: **corresponds to intensity

- Timbre (音色): corresponds to complexity

Physical and Perceptual Dimensions of Sound Waves:

Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 380 and 760 nm is visible to humans.

Vibration ranges between approximately 30 and 20,000 Hz is auditable to humans

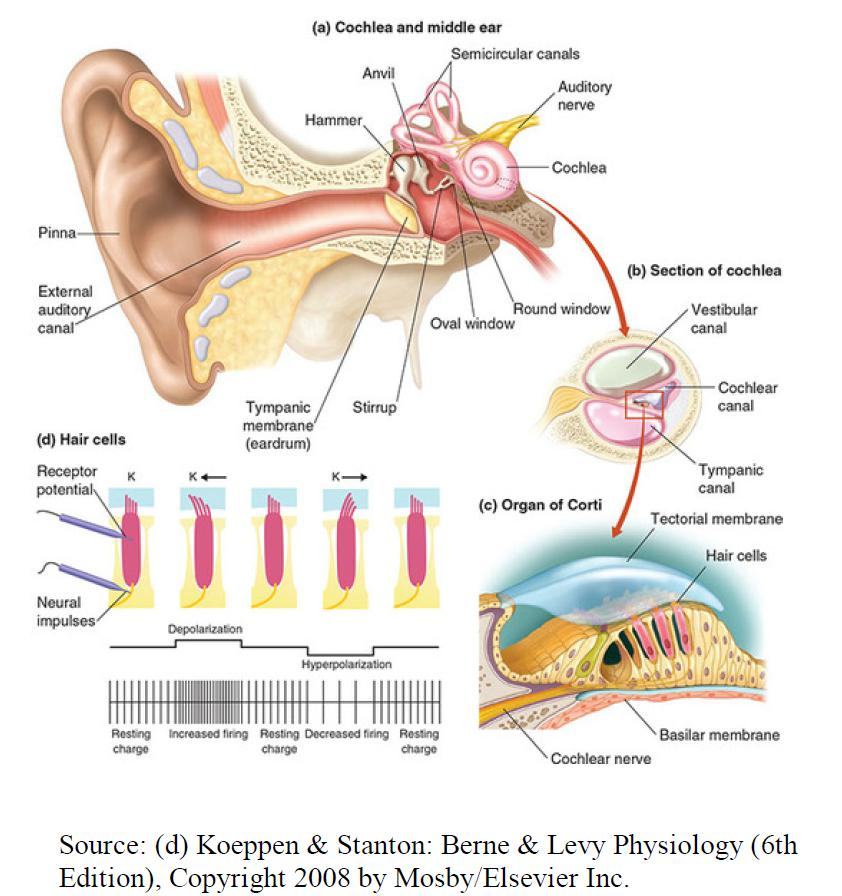

Anatomy of the Ear

1. The Auditory Apparatus

Overview

- Tympanic membrane (鼓膜): The eardrum

- Ossicle (听小骨): One of the three bones of the middle ear.

- Malleus (锤骨): The “hammer”; the first of the three ossicles.

- Incus (砧骨): The “anvil”; the second of the three ossicles

- Stapes (镫骨): The “stirrup”; the last of the three ossicles

- Cochlea (耳蜗): The snail-shaped structure of the inner ear that contains the auditory transducing mechanisms

- Oval window (卵圆窗): An opening in the bone surrounding the cochlea that reveals a membrane, against which the baseplate of the stapes presses, transmitting sound vibrations into the fluid within the cochlea.

- Round window (圆形窗): An opening in the bone surrounding the cochlea of the inner ear that permits vibrations to be transmitted, via the oval window, into the fluid in the cochlea

The Cochlea

The name cochlea comes from the Greek word kokhlos, or “land snail”.

It is indeed snail-shaped, consisting of two and three-quarters turns of a gradually tapering cylinder, 35 mm (1.37 in.) long.

The cochlea is divided longitudinally into three sections, the scala vestibuli (“vestibular stairway”), the scala media (“middle stairway”), and the scala tympani (“tympanic stairway”)

- Organ of Corti (柯替氏器): The sensory organ on the basilar membrane that contains the auditory hair cells.

- Hair cell (听毛细胞): The receptive cell of the auditory apparatus

- Deiters’s cell: A supporting cell found in the organ of Corti; sustains the auditory hair cells.

- Basilar membrane (耳蜗基底膜): A membrane in the cochlea of the inner ear; contains the organ of Corti

- Tectorial membrane (耳蜗覆膜, 柯替氏膜): A membrane located above the basilar membrane; serves as a shelf against which the cilia of the auditory hair cells move.

- Cochlear nerve (耳蜗神经): The branch of the auditory nerve that transmits auditory information from the cochlea to the brain.

2. Responses to Sound Waves

When the stapes pushes against the membrane behind the oval window, the membrane behind the round window bulges outward. Different high-frequency and medium-frequency sound vibrations cause flexing of different portions of the basilar membrane. In contrast, low frequency sound vibrations cause the tip of the basilar membrane to flex in synchrony with the vibrations.

Auditory Hair Cells and the Transduction of Auditory Information

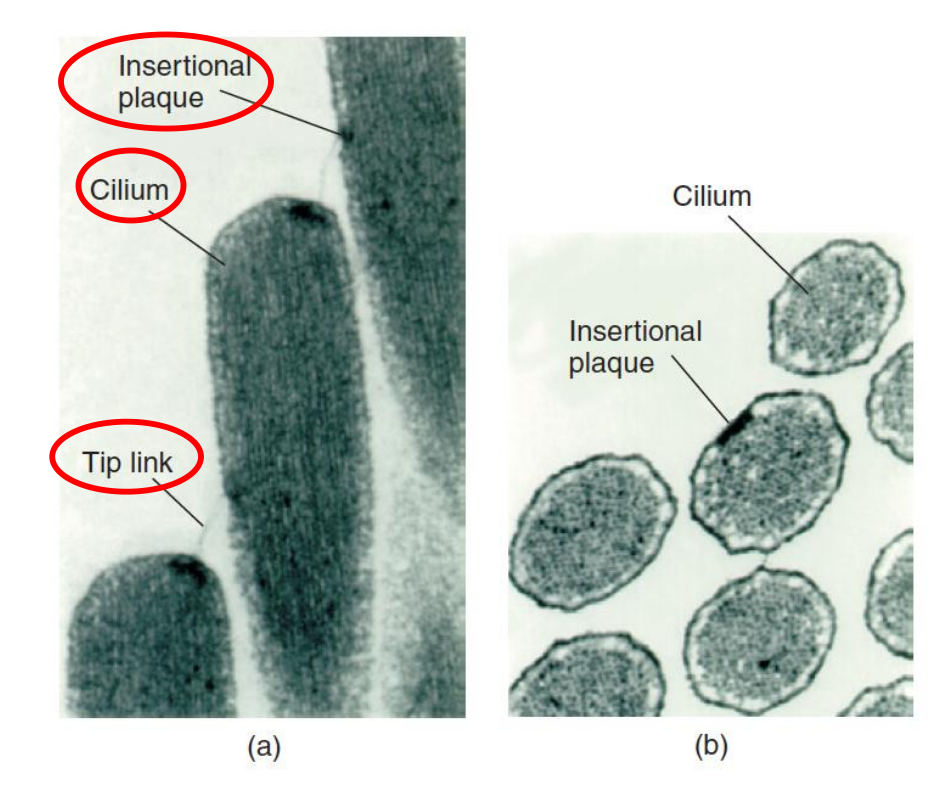

Transduction Apparatus in Hair Cells:

- Cilium (纤毛) (plural: cilia): A hair-like appendage of a cell involved in movement or in transducing sensory information; found on the receptors in the auditory and vestibular system

- Tip link (顶连): An elastic filament that attaches the tip of one cilium to the side of the adjacent cilium

- Insertional plaque (附着斑): The point of attachment of a tip link to a cilium.

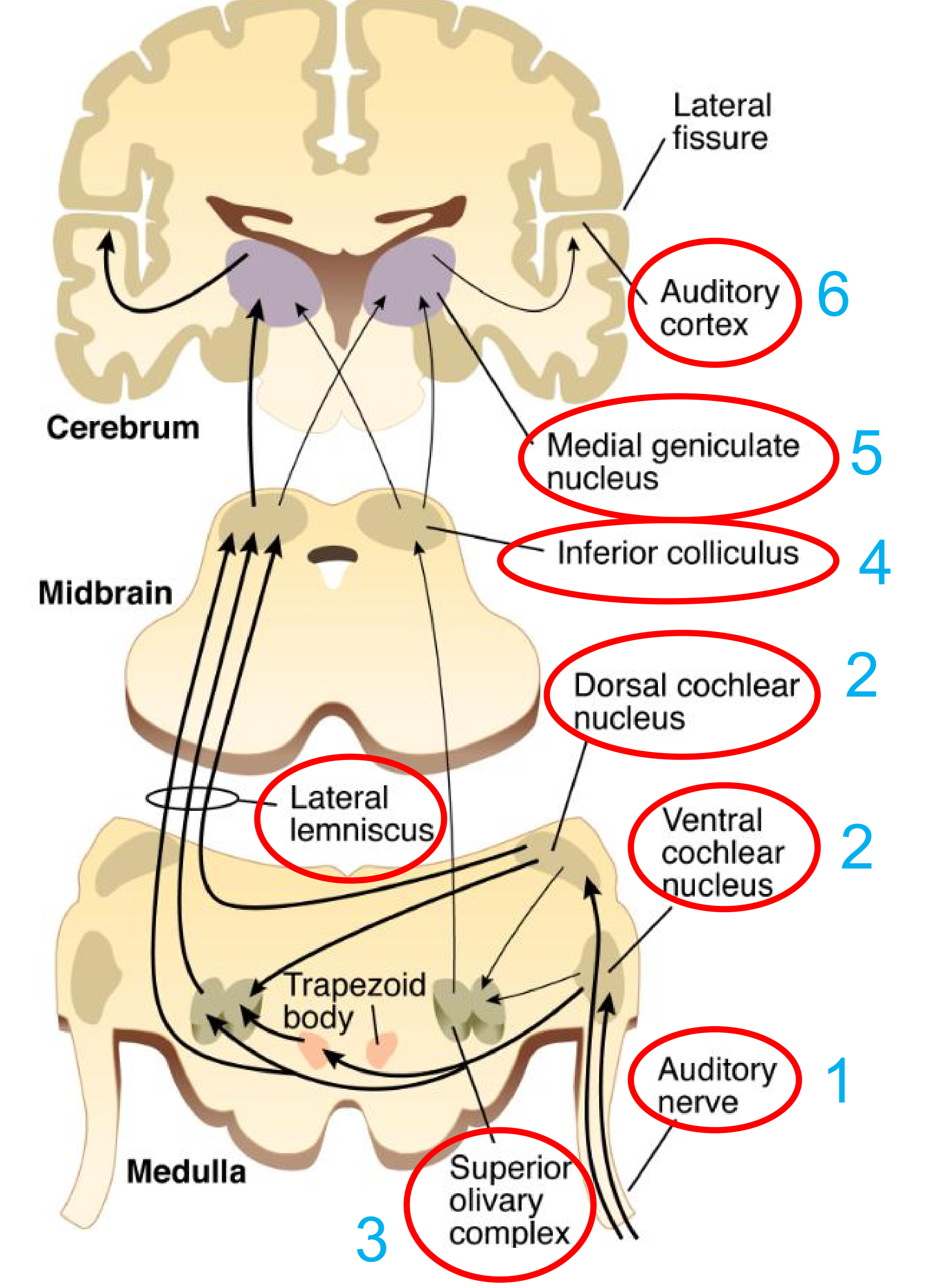

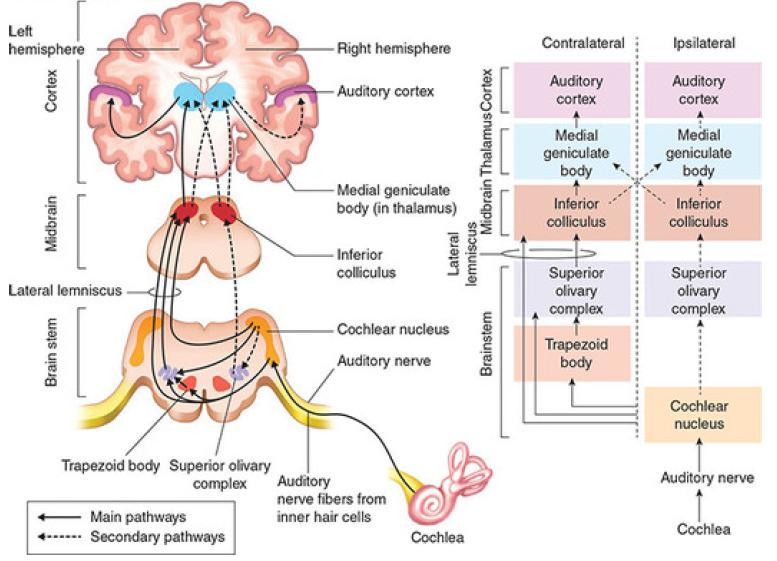

The Auditory Pathway

1. The Transport order (Pathway)

- Cochlear nerve (耳蜗神经): The branch of the auditory nerve that transmits auditory information from the cochlea to the brain

In The Central Auditory System

- Cochlear nucleus (耳蜗核): One of a group of nuclei in the medulla that receive auditory information from the cochlea.

- Superior olivary complex (橄榄复合体;上橄榄核复合体): A group of nuclei in the medulla; involved with auditory functions, including localization of the source of sounds.

- Lateral lemniscus (外侧丘系;外侧蹄系): A band of fibers running rostrally through the medulla and pons; carries fibers of the auditory system.

- Inferior colliculus (下丘;下丘中脑顶盖尾部隆起;下丘核)

- Medial geniculate nucleus (内侧膝状体核;内侧膝状核;丘脑的内膝核)

- Auditory cortex (听觉皮质)

- Auditory information from the cochlea ascends through many brain areas before arriving at the auditory cortex. Most auditory information crosses to the opposite(contralateral) hemisphere between the cochlear nucleus and trapezoid body, but some stays on the same side (ipsilateral) as the cochlea

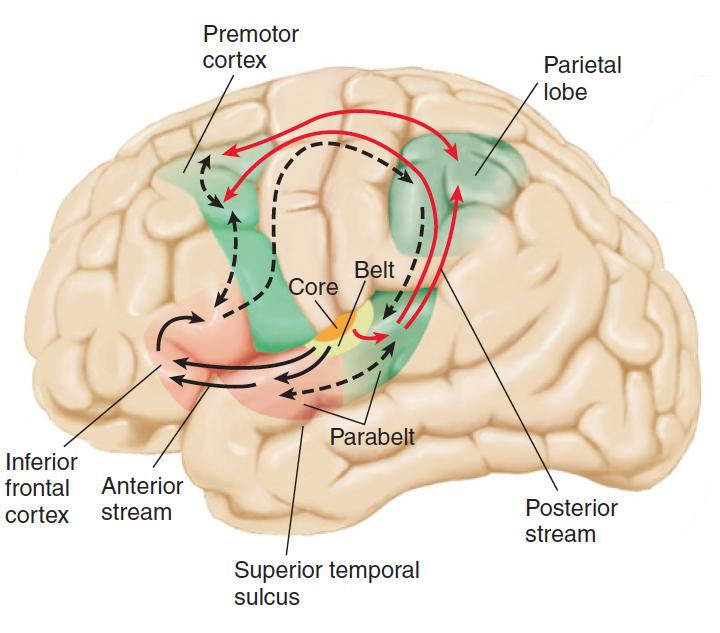

2. The Auditory Cortex

- Tonotopic representation: A topographically organized mapping of different frequencies of sound that are represented in a particular region of the brain.

- Core region: The primary auditory cortex, located on a gyrus on the dorsal surface of the temporal lobe.

- Belt region: The first level of auditory association cortex; surrounds the primary auditory cortex.

- Parabelt region: The second level of auditory association cortex; surrounds the belt region

Auditory information from the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus is received by the primary auditory cortex (core region). Information analyzed by the core region is transmitted to the belt region, and from there to the anterior and posterior parabelt region.

- The anterior parabelt region serves as the beginningof the anterior stream, which is involved with the analysis of complex sounds.

- The posterior parabelt region serves as the beginning of the posterior stream, which is involved with the analysis of sound localization.

Perception of Pitch

As we have seen, the perceptual dimension of pitch corresponds to the physical dimension of frequency

The cochlea detects frequency by two means:

- moderate to high frequencies by place coding

- low frequencies by rate coding.

Place code:

- The system by which information about different frequencies is coded by different locations on the basilar membrane.

Rate code:

- System by which information about different frequencies of sound waves is coded by rate of firing of neurons in auditory system

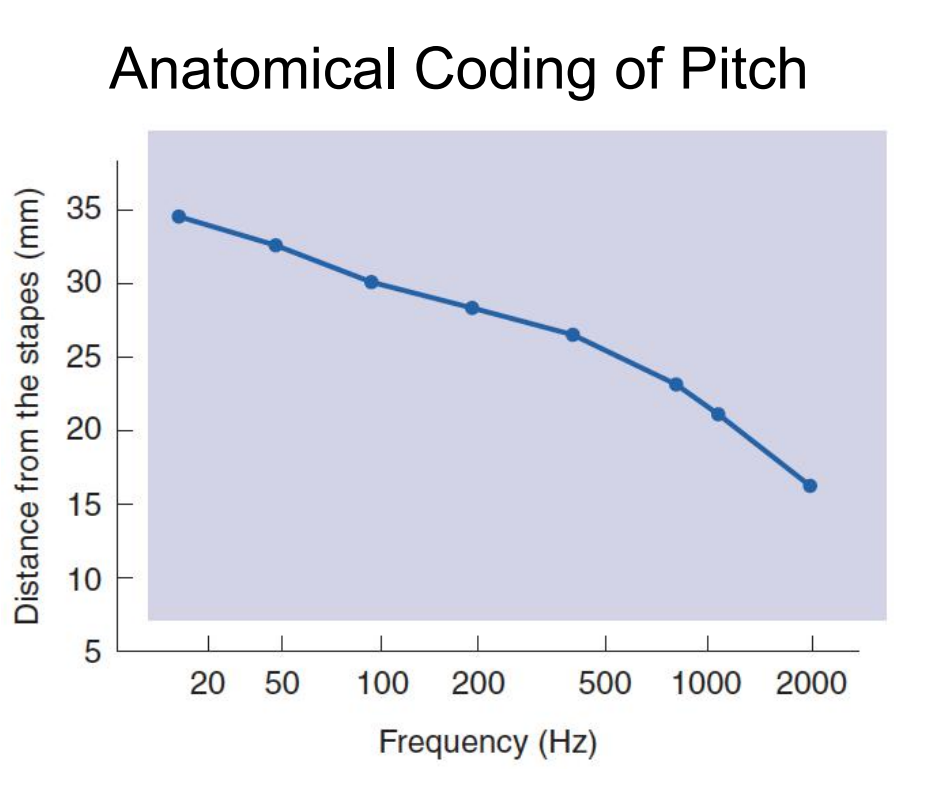

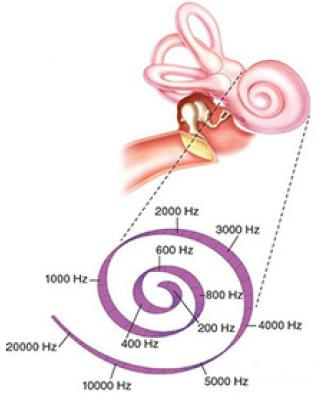

1. Place Coding

Because of the mechanical construction of the cochlea and basilar membrane, acoustic stimuli of different frequencies cause different parts of the basilar membrane to flex back and forth

Note that higher frequencies produce more displacement at the basal end of the membrane (the end closest to the stapes).

This figure illustrates the amount of deformation along the length of the basilar membrane produced by stimulation with tones of various frequencies.

Stimuli of different frequencies maximally deform different regions of the basilar membrane.

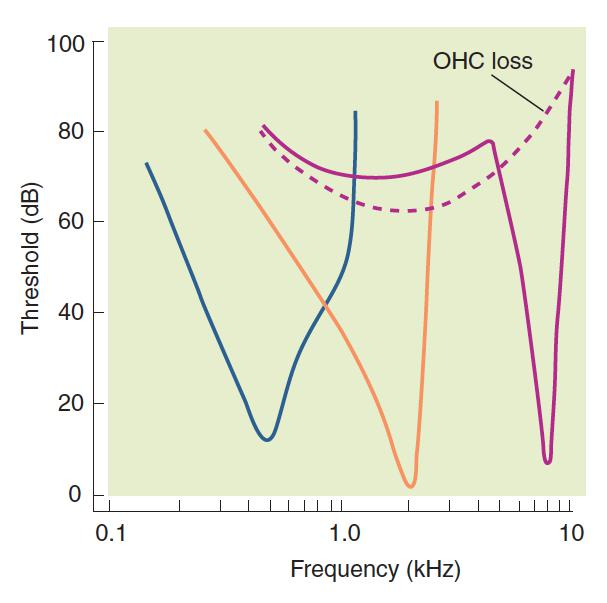

- This figure - illustrates the importance of outer hair cells to sensitivity and frequency selectivity of inner hair cells (Fettiplace and Hackney 2006).

- Three V-shaped tuning curves indicate sensitivity of individual inner hair cells, as shown by the response of individual afferent auditory nerve axons to pure tones.

- Low points of three solid curves indicate that hair cells will respond to faint sound only if it is of a specific frequency—for these cells, either 0.5 kHz (blue curve), 2.0 kHz (orange curve), or 8.0 kHz (purple curve).

- If sound is louder, cells will respond to frequencies above and below their preferred frequencies

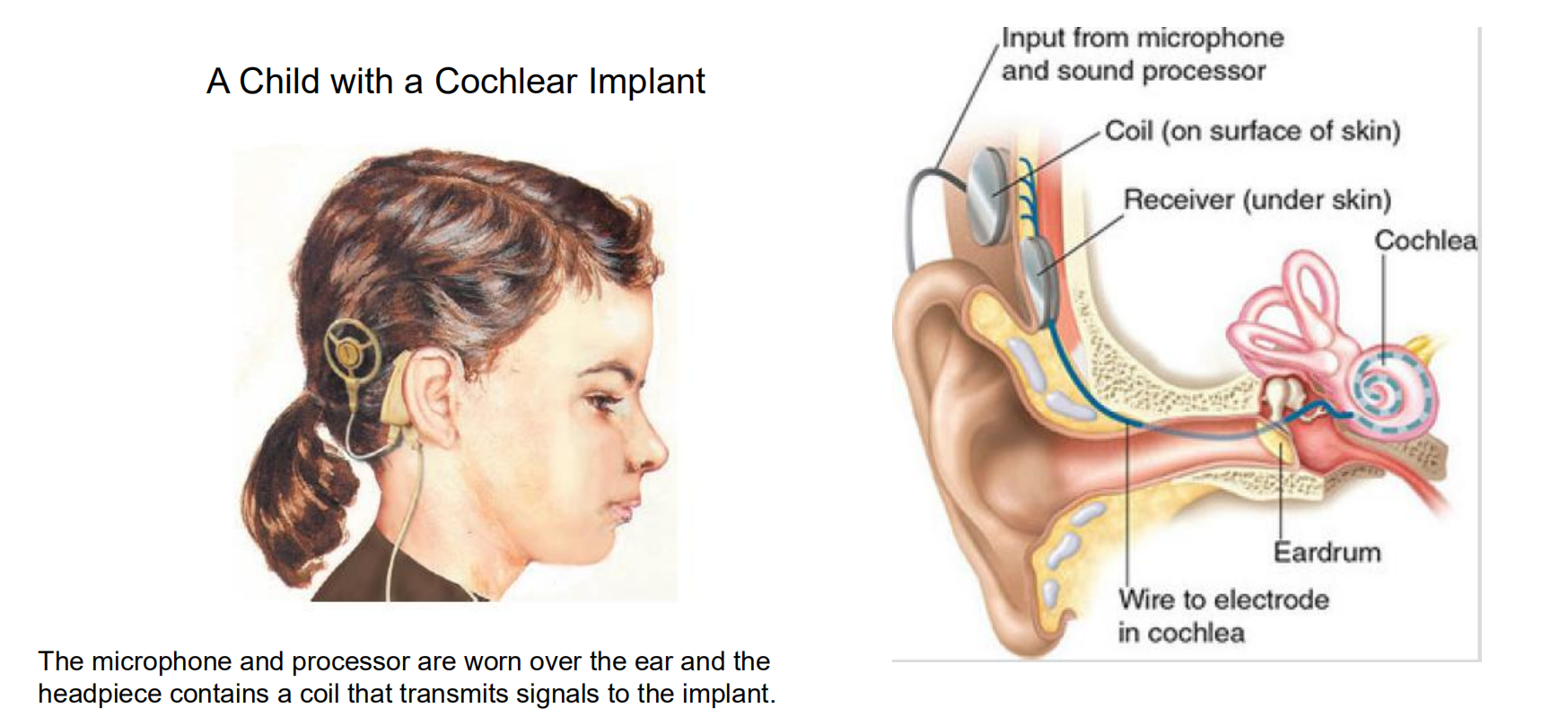

- Good evidence for place coding of pitch in the human cochlea comes from the effectiveness of cochlear implants. Cochlear implants are devices that are used to restore hearing in people with deafness caused by damage to the hair cells. The external part of a cochlear implant consists of a microphone and a miniaturized electronic signal processor.

- The internal part contains a very thin, flexible array of electrodes, which the surgeon carefully inserts into the cochlea in such a way that it follows the snaillike curl and ends up resting along the entire length of the basilar membrane. Each electrode in the array stimulates a different part of the basilar membrane. Information from the signal processor is passed to the electrodes by means of flat coils of wire, implanted under the skin

- The primary purpose of a cochlear implant is to restore a person’s ability to understand speech. Because most of the important acoustical information in speech is contained in frequencies that are too high to be accurately represented by a rate code, the multichannel electrode was developed in an attempt to duplicate the place coding of pitch on the basilar membrane (Copeland and Pillsbury, 2004). When different regions of the basilar membrane are stimulated, the person perceives sounds with different pitches.

- The signal processor in the external device analyzes the sounds detected by the microphone and sends separate signals to the appropriate portions of the basilar membrane. This device can work well; most people with cochlear implants can understand speech well enough to use a telephone (Shannon, 2007)

Tonotopic map 音高地图

- 频率的反应而排列;频率排列的特性;音高地图

- The part of the auditory cortex at the left end of this view receives neurons from the apex of the cochlea, and the other end responds to signals from the base. The auditory cortex thus forms a “map” of the basilar membrane so that each successive area responds to progressively higher frequencies.

- The lowest point of each curve indicates that neuron’s primary frequency and the lowest amplitude of sound that will activate the neuron. Other frequencies within the curve will also activate that neuron, but activation decreases with distance from the primary frequency.

2. Rate coding

We have seen that the frequency of a sound can be detected by place coding. However, the lowest frequencies do not appear to be accounted for in this manner. Lower frequencies are detected by neurons that fire in synchrony to the movements of the apical end of the basilar membrane. Thus, lower frequencies are detected by means of rate coding

The most convincing evidence of rate coding of pitch also comes from studies of people with cochlear implants. Pijl and Schwarz (1995a, 1995b) found that stimulation of a single electrode with pulses of electricity produced sensations of pitch that were proportional to the frequency of the stimulation

- In fact, the subjects could even recognize familiar tunes produced by modulating the pulse frequency. (The subjects had become deaf later in life, after they had already learned to recognize the tunes.) As we would expect, the subjects’ perceptions were best when the tip of the basilar membrane was stimulated, and only low frequencies could be distinguished by this method

Perception of Timbre

Although laboratory investigations of the auditory system often employ pure sine waves as stimuli, these waves are seldom encountered outside the laboratory

- Instead, we hear sounds with a rich mixture of frequencies—sounds of complex timbre. For example, consider the sound of a clarinet playing a particular note

- If we hear it, we can easily say that it is a clarinet and not a flute or a violin.

- The reason we can do so is that these three instruments produce sounds of different timbre, which our auditory system can distinguish.

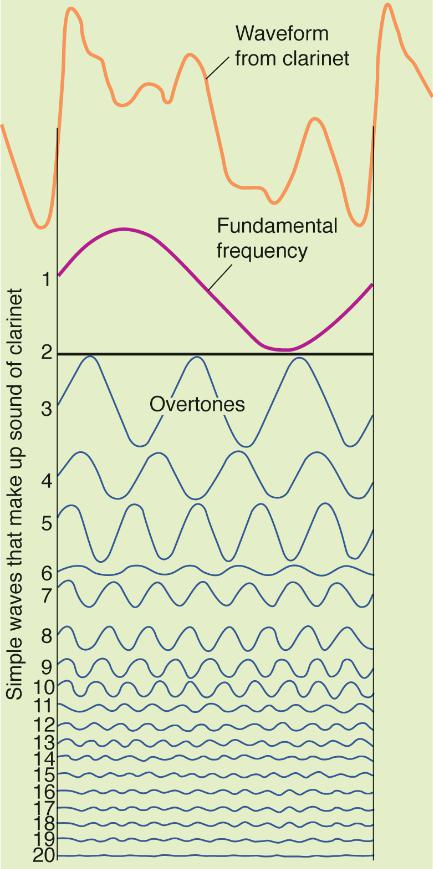

Sound Wave from a Clarinet(单簧管):

- Fundamental frequency(基频): The lowest, and usually most intense, frequency of a complex sound; most often perceived as the sound’s basic pitch.

- Overtone(泛音): The frequency of complex tones that occurs at multiples of the fundamental frequency

- This figure shows the waveform from a clarinet playing a steady note (top). The shape of the waveform repeats itself regularly at the fundamental frequency , which corresponds to the perceived pitch of the note

- A Fourier analysis of the waveform shows that it actually consists of a series of sine waves that includes the fundamental frequency and many overtones , multiples of the fundamental frequency. Different instruments produce overtones with different intensities.

- Electronic synthesizers simulate the sounds of real instruments by producing a series of overtones of the proper intensities, mixing them, and passing them through a loudspeaker.

When the basilar membrane is stimulated by the sound of a clarinet, different portions respond to each of the overtones. This response produces a unique anatomically coded pattern of activity in the cochlear nerve, which is subsequently identified by circuits in the auditory association cortex.

Perception of Spatial Location

We can hear continuous sounds as well as clicks, and we can also perceive the location of their source

- The most obvious way to locate a sound is to turn your head until the sound is loudest. This is not very effective, because the sound may be gone before the direction is located

Three additional cues permit us to locate sounds quickly and accurately, including those that are too brief to allow turning the head.

All three of these cues are binaural, meaning that they involve the use of two ears; the brain determines the location based on acoustic differences between the two ears.

These cues are useless when a sound source is in the median plane (equidistant from the person’s ears), but if the sound is shifted to one side, the stimulus will differ between the ears.

Animals with ears that are very close together (such as mice) are at a disadvantage in locating sounds because the differences are so small

Grasshoppers and crickets have evolved a compensation for their small head size: Their auditory organs are on their legs, as far apart as possible.

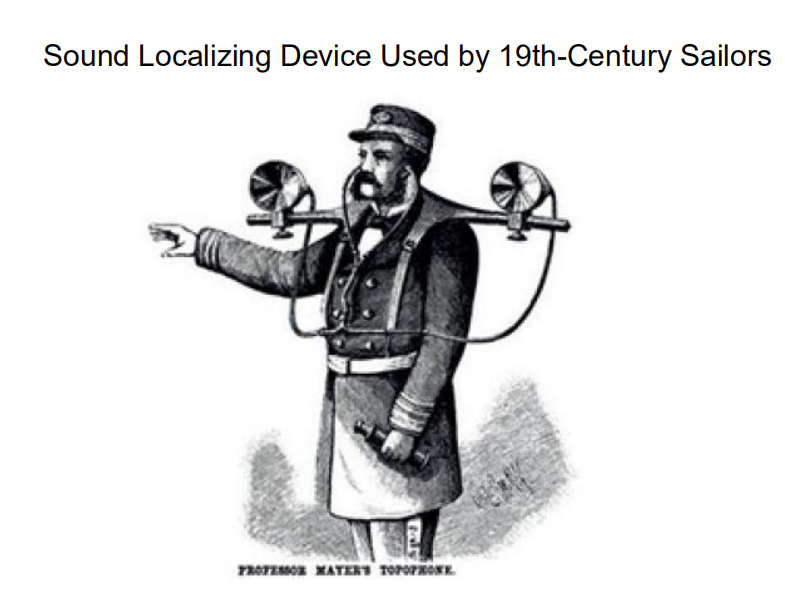

- Nineteenth-century sailors used a novel application of this strategy when they needed to locate a distant sound source: They listened through tubes attached to funnels at the ends of a long rod called a topophone

- By listening through devices on a long rod (calldeda topophone), sailors effectively increased the distance between their ears and enchanced the binaural cues

The three additional cues are:

- Binaural differences of intensity, timing, and phase.

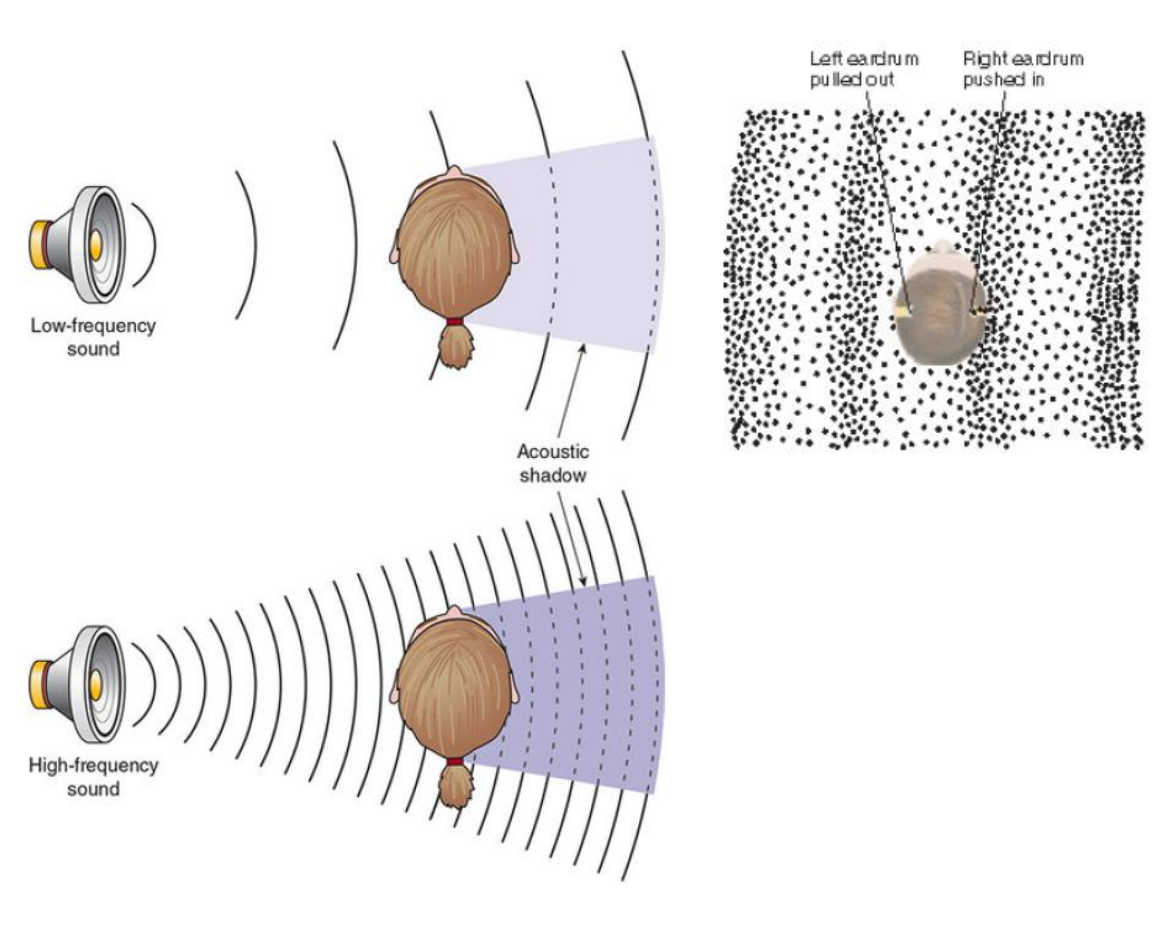

1. Differential Intensity and Timing as Cues for Sound Localization.

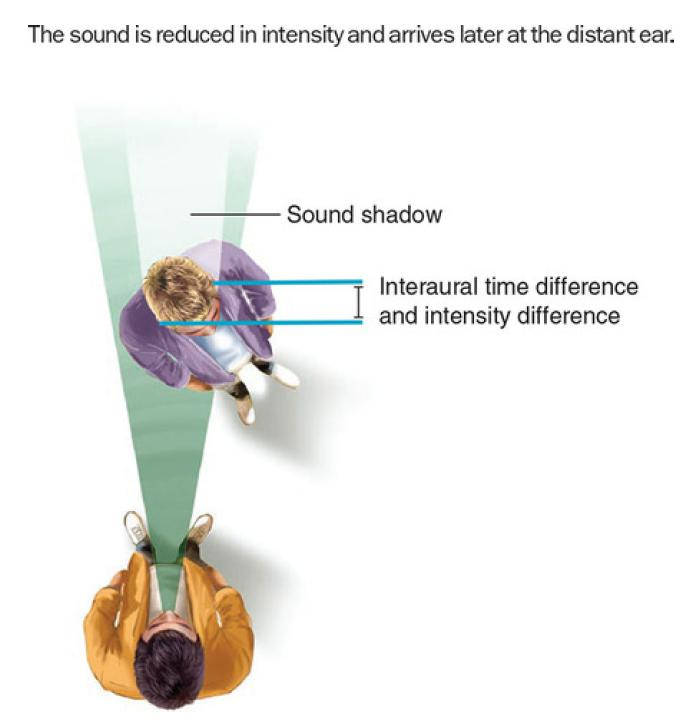

- When a sound source is on one side, the head blocks some of the sound energy. The sound shadow this creates produces an interaural intensity (or level) difference (IID or ILD,耳间强度差异,水平差异), so that the near ear receives a more intense sound the more it is to that side.

- Some of the neurons of the lateral superior olivary nucleus (LSO, located in the brain stem) respond to differences in IID at the two ears using a simple subtraction mechanism (far ear being excitatory, near ear being inhibitory).

- Because low frequency sounds tend to pass through solid objects (like the head), this cue works best when the sound is above 2000 Hz.

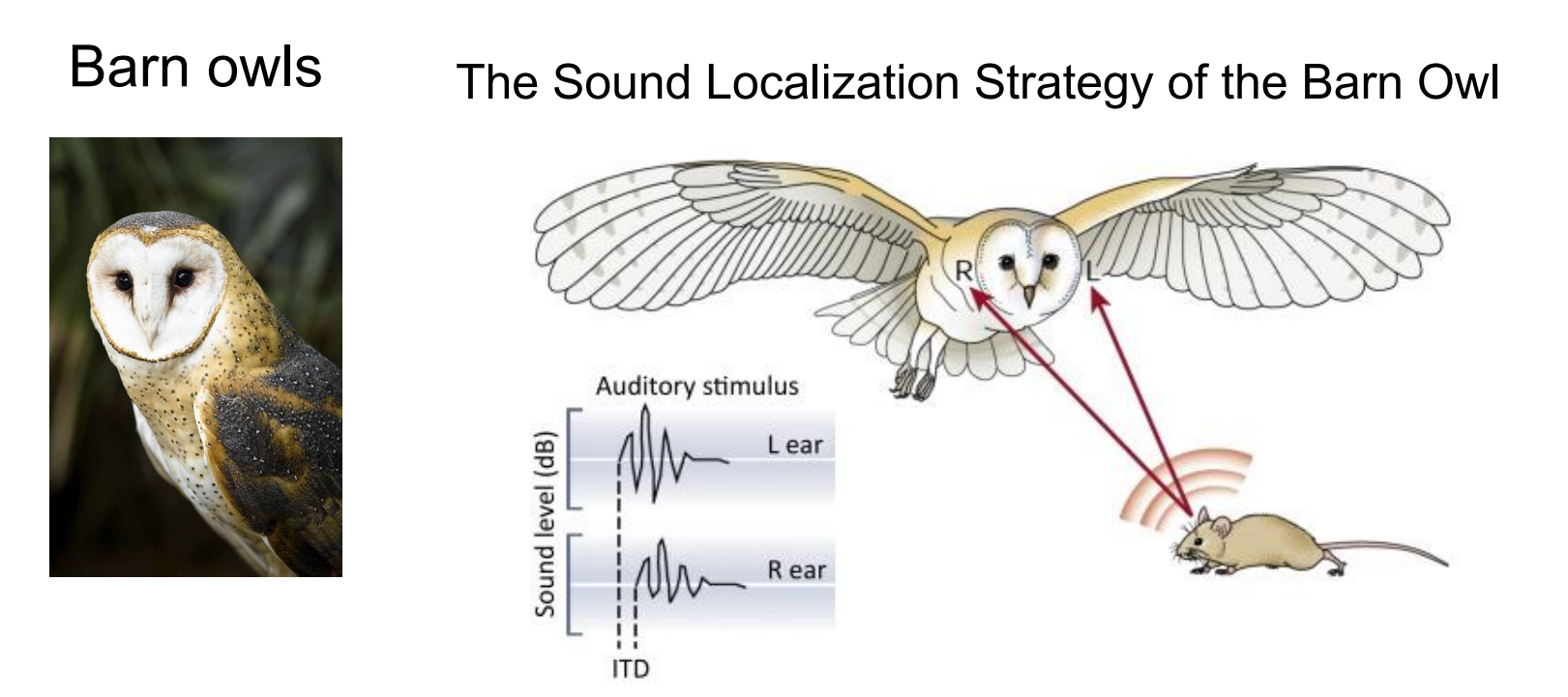

- The second binaural cue for locating sounds is interaural timing difference (ITD) at the two ears. A sound that is directly to a person’s left or right takes about 0.5 milliseconds to travel the additional distance to the second ear; humans can detect an ITD difference as small as 10 microseconds, which means we can locate sound sources that move by as little as a degree horizontally

- This computation is done in the medial superior olivary nucleus (MSO). Although components of our auditory system can respond to smaller angles of separation, we cannot distinguish such small intervals consciously; this kind of precision involves automatic processing by specialized circuits.

2. Phase Difference as a Cue for Sound Localization

- At low frequencies, a sound arriving from one side of the body will be at a different phase of the wave at each ear, referred to as an interaural phase difference (IPD) . As a result, at a given moment one eardrum will be pushed in more or less than the other or, one will be pushed in while the other is being pulled out.

- Some of the neurons in the superior olivary nucleus respond only when the inputs from the two ears have different IPD values.

- Above about 1500 Hz, a sound will have begun a new wave by the time it reaches the second ear, introducing something called phase ambiguity, which makes localizing sounds more difficult.

- Barn owls can accurately localize prey based on interaural disparities even in total darkness. If, for instance, the sound origin is slightly to the left from the vertical and below the horizontal midline, it will arrive at the left ear slightly earlier (interaural time difference, ITD) and with a somewhat larger amplitude (interaural level difference, ILD). (B,C) Barn owls belong to the group of asymmetrical owls. The asymmetry of their skull does not significantly affect ITDs

- Determining the direction/location of a sound, must be integrated with information from the visual environment and information about the position of the body in space. The combining all this information is the function of association areas in the parietal lobes

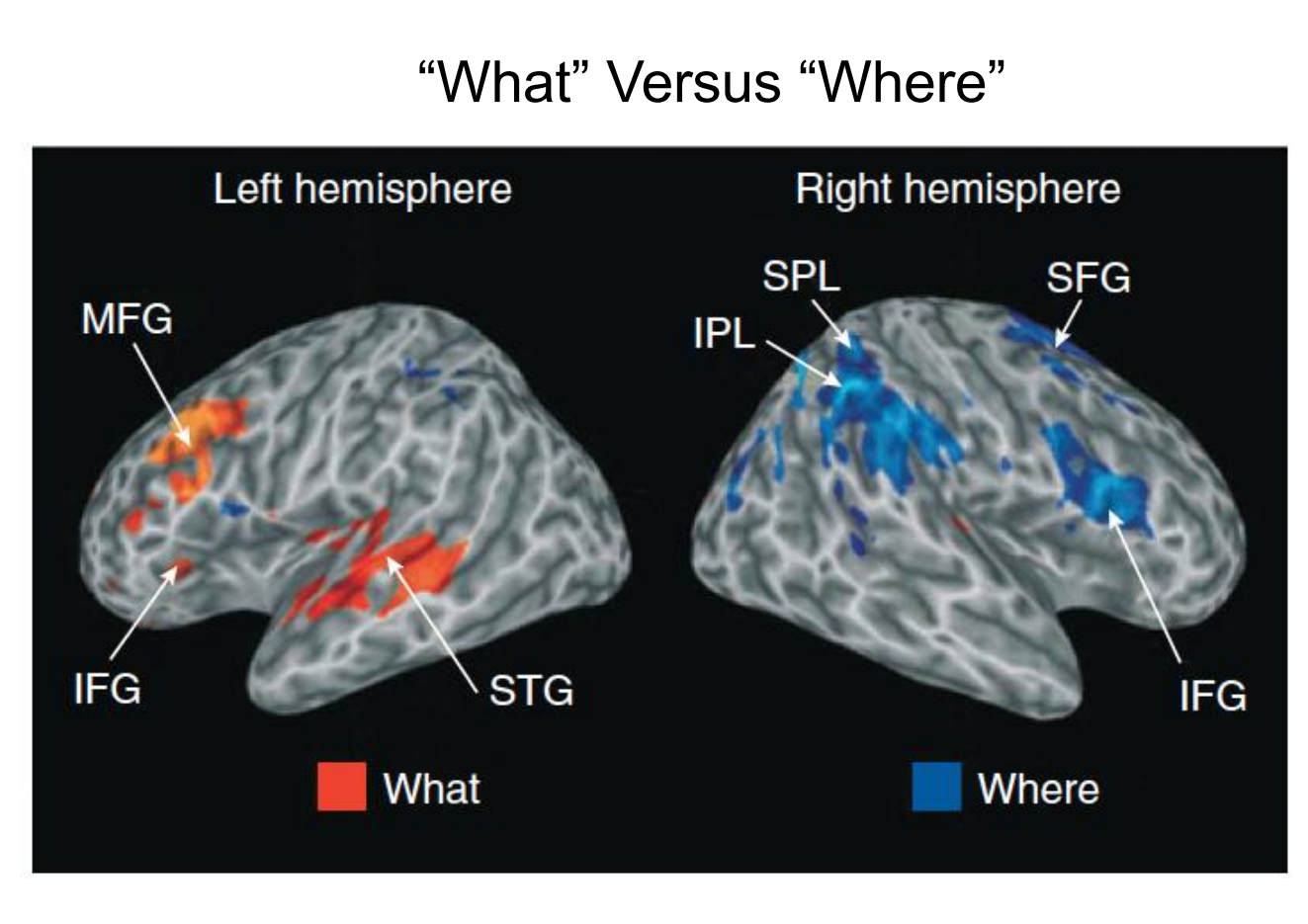

- Identifying sounds occurs in the “what” stream.

- locating sounds in space occurs in the dorsal “where” stream.

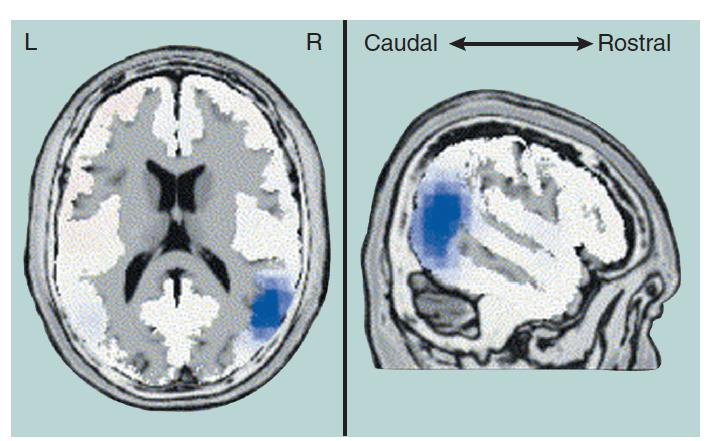

- This figure shows regional brain activity in response to judgments of category (red) and location (blue) of sounds.

- IFG = inferior frontal gyrus,

- IPL = inferior parietal lobule,

- MFG = middle frontal gyrus,

- SFG = superior frontal gyrus,

- SPL = superior parietal lobule.

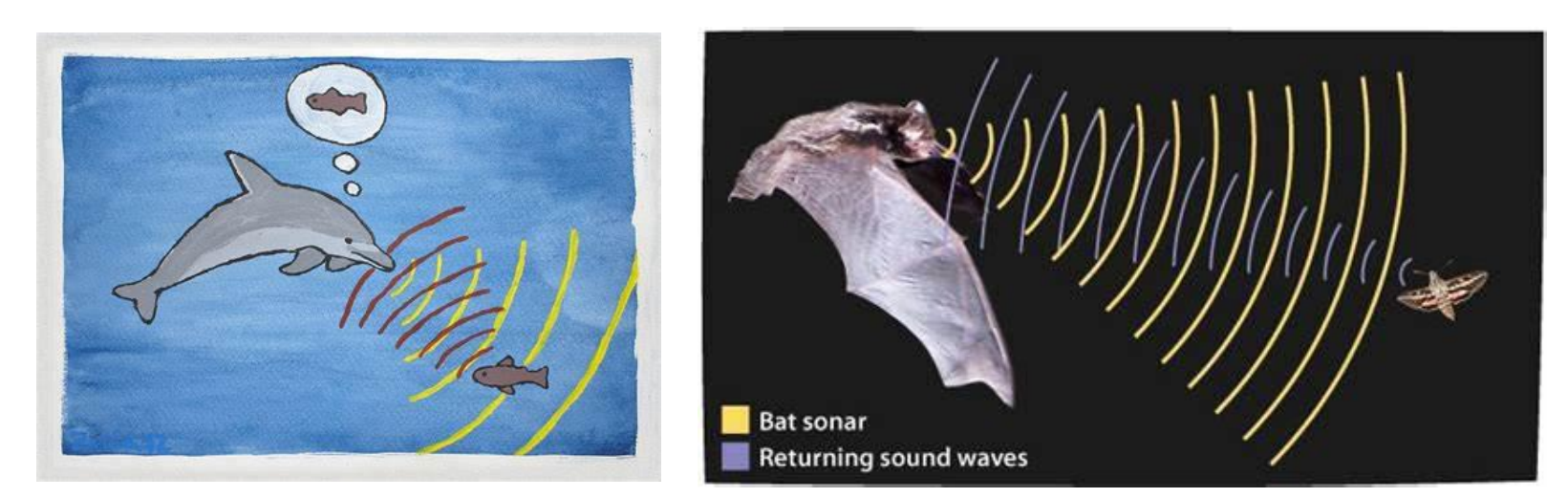

- The ultimate in sound localization is echolocation, a sort of sonar that bats, dolphins, whales, and even some cave-dwelling birds use to avoid obstacles and to detect prey and predators. Bats are so proficient that they can use the echoes of their ultrasonic chirps to catch insects while avoiding obstacles in total darkness (see Ulanovsky & Moss, 2008).

- We are currently using knowledge gained from echolocating mammals not only to demonstrate people who can echolocate but also to design new devices that use sound to help people see, which is the subject of the accompanying Application.

Perception of Complex Sounds - Identify a Sound

Beyond distinguishing one sound from another, it is important to be able to identify a sound. Here it is useful to think in terms of an auditory object —a sound we identify as distinct from other sounds.

Identifying an auditory object involves distinguishing characteristics such as pitch, rhythm(节奏), and tempo(节拍). Understand that identifying an auditory object does not imply that we recognize what the sound is; memory helps provide that function, enabling us to recognize an oncoming train or the voice of a friend.

Dolphins can even recognize the signature whistle of former tank mates from as far back as 20 years, the typical dolphin lifespan in the wild (Bruck, 2013). Recognizing environmental sounds primarily requires posterior temporal areas and, to a lesser extent, the frontal cortex (J. W. Lewis et al., 2004), while recognizing individuals’ voices involves the secondary auditory cortex in the superior temporal area (Kriegstein & Giraud, 2004; Petkov et al., 2008). More generally, these sound objects activate the “what” pathway. These areas are also important in producing and understanding language.

1. The Dorsal “Where” and Ventral “What” Streams of Auditory Processing

The red areas (dorsal stream, where stream) where active when subjects determined the locations of sounds.

Green area (ventral stream, what stream) were activated when they identified sounds. Localization and identification followed dorsal “where” and ventral “what” streams, respectively, with both terminating in frontal areas. (fMRI data were superimposed over a smoothed brain)

Hearing has three primary functions:

- to detect sounds

- to determine the location of their sources

- to recognize the identity of these sources—and thus their meaning and relevance to us

2. Perception of Environmental Sounds and Their Location

The superior auditory abilities of blind people has long been recognized: Loss of vision appears to increase the sensitivity of the auditory system

A functional imaging study by Klinge et al. (2010) found that input to the auditory cortex was identical in blind and sighted people, but that neural connections between the auditory cortex and the visual cortex were stronger in blind people.

In addition, the visual cortex showed enhanced responsiveness to auditory stimuli

These findings suggest that the analysis of auditory stimuli can be extended to the visual cortex in blind people.

3. Perception of Music

Different regions of the brain are involved in different aspects of musical perception (Peretz and Zatorre, 2005).

For example, the inferior frontal cortex appears to be involved in recognition of harmony, the right auditory cortex appears to be involved in perception of the underlying beat in music.

Evidence suggests that neural circuits used to process music are already present in newborn infants

A functional imaging study by Perani et al. (2010) found that 1to 3-day-old infants showed changes in brain activity (primarily in the right hemisphere) when music they were hearing changed key.

- Brain activity also altered when babies heard dissonant music, which adults find unpleasant

In humans, the most elaborate processing of auditory information occurs in language

McGurk Effect

McGurk effect is a cross-modal effect and illusion that results from conflicting information coming from different senses, namely sight and hearing. The effect was discovered by Harry McGurk and John MacDonald, and was published in Nature in 1976

It shows the interaction between hearing and vision in the process of speech perception. Sometimes, human hearing is too much affected by vision, resulting in the phenomenon of mishearing. When one sound seen by the vision does not match another sound heard by the ear, people will mysteriously detect the third sound

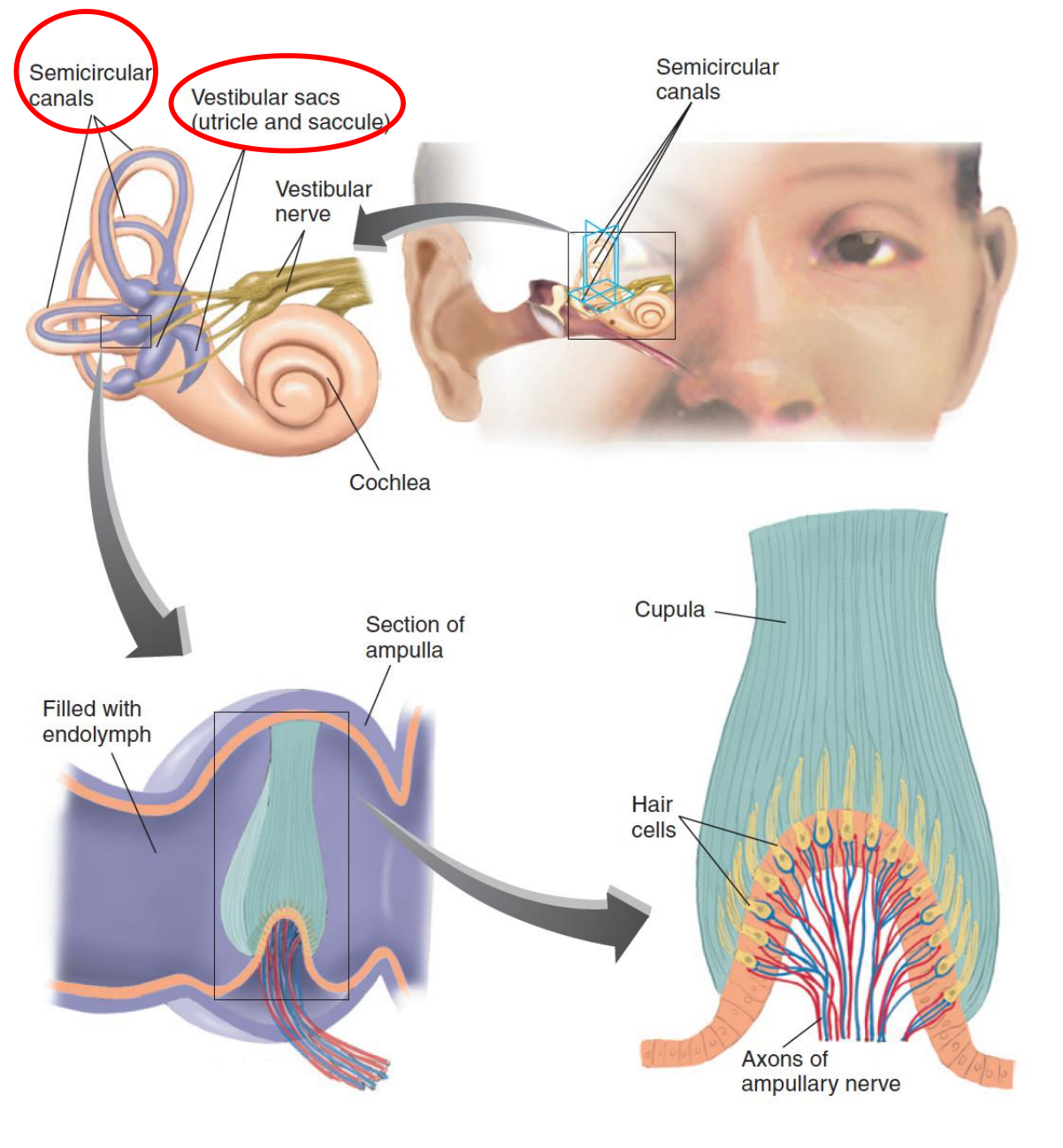

二、Vestibular System

The functions of the vestibular system include balance, maintenance of the head in an upright position, and adjustment of eye movement to compensate for head movements.

Vestibular stimulation does not produce any readily definable sensation; certain low-frequency stimulation of the vestibular sacs can produce nausea, and stimulation of the semicircular canals can produce dizziness and rhythmic eye movements (nystagmus).

Anatomy of the Vestibular Apparatus

- Vestibular sac (前庭囊): One of a set of two receptor organs in each inner ear that detect changes in the tilt of the head.

- Semicircular canal ((耳的)半规管): One of the three ring-like structures of the vestibular apparatus that detect changes in head rotation

- Utricle (椭圆囊;前列腺囊): One of the vestibular sacs.

- Saccule (小囊;耳迷路的球囊): One of the vestibular sacs.

- Ampulla (壶腹): An enlargement in a semicircular canal; contains the cupula and the crista.

- Cupula (顶;壳斗;杯状托): A gelatinous mass found in the ampulla of the semicircular canals; moves in response to the flow of the fluid in the canals

The Receptive Tissue of the Vestibular Sacs: The Utricle and the Saccule

The Vestibular Pathway

The vestibular and cochlear nerves constitute the two branches of the eighth cranial nerve (auditory nerve).

The bipolar cell bodies that give rise to the afferent axons of the vestibular nerve (a branch of the eighth cranial nerve) are located in the vestibular ganglion, which appears as a nodule on the vestibular nerve

1. Vestibular ganglion

A nodule on the vestibular nerve that contains the cell bodies of the bipolar neurons that convey vestibular information to the brain

三、Speech Production and Comprehension

Our knowledge of the physiology of language has been obtained primarily by observing the effects of brain lesions on people’s verbal behavior.

Aphasia: Difficulty in producing or comprehending speech not produced by deafness or a simple motor deficit; caused by brain damage.

Speech Production

Being able to talk—that is, to produce meaningful speech—requires several abilities.

First, the person must have something to talk about. We can talk about something that is currently happening or something that happened in the past. In the first case we are talking about our perceptions: things we are seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, and so on. In the second case we are talking about our memories of what happened in the past. Both perceptions of current events and memories of events that occurred in the past involve brain mechanisms in the posterior part of the cerebral hemispheres (the occipital, temporal, and parietal lobes). Thus, this region is largely responsible for our having something to say.

Given that a person has something to say, actually saying it requires some additional brain functions. As we shall see in this section, the conversion of perceptions, memories, and thoughts into speech makes use of neural mechanisms located in the frontal lobes.

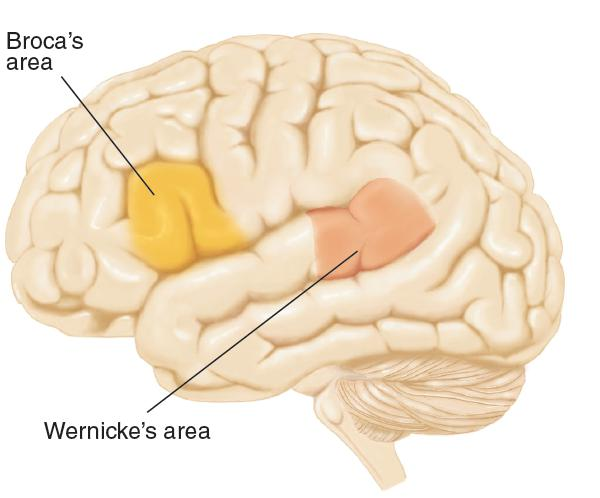

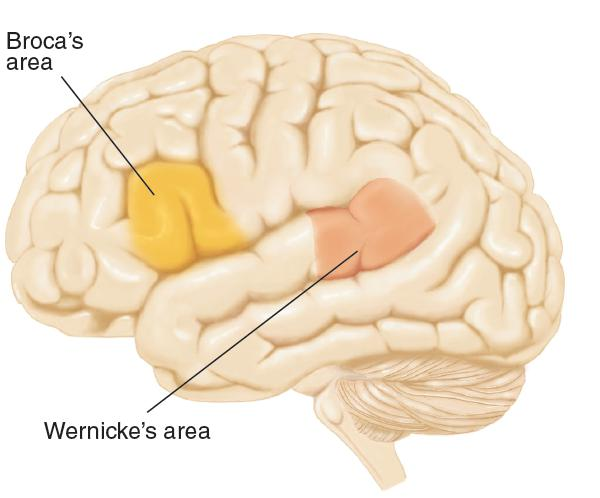

1. Lateralization

Verbal behavior is a lateralized function; most language disturbances occur after damage to the left side of the brain.

- The left hemisphere of approximately 90% of the total population is dominant for speech.

Although the circuits that are primarily involved in speech comprehension and production are located in one hemisphere (almost always, the left hemisphere), it would be a mistake to conclude that the other hemisphere plays no role in speech.

When we hear and understand words, and when we talk about or think about our own perceptions or memories, we are using neural circuits besides those directly involved in speech.

Thus, these circuits also play a role in verbal behavior. For example, damage to the right hemisphere makes it difficult for a person to read maps, perceive spatial relations, and recognize complex geometrical forms.

People with such damage also have trouble talking about things like maps and complex geometrical forms or understanding what other people have to say about them.

The right hemisphere also appears to be involved in organizing a narrative—selecting and assembling the elements of what we want to say. The right hemisphere is involved in the expression and recognition of emotion in the tone of voice. And it is also involved in control of prosody—the normal rhythm and stress found in speech.

- Therefore, both hemispheres of the brain have a contribution to make to our language abilities.

2. Speech Areas

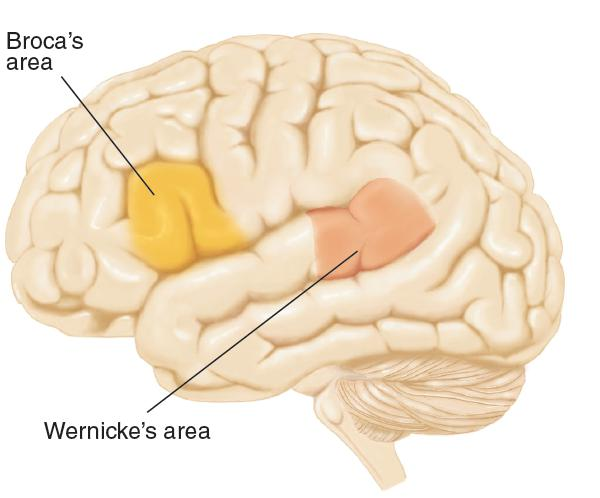

- This shows the location of the primary speech areas of the brain

Broca’s area: A region of frontal cortex, located just rostral to the base of the left primary motor cortex, that is necessary for normal speech production.

- Broca (1861) suggested that this form of aphasia is produced by a lesion of the frontal association cortex, just anterior to the face region of the primary motor cortex

- Subsequent research proved him to be essentially correct, and we now call the region Broca’s area.

What do the neural circuits in and around Broca’s area do? Wernicke

- (1874) suggested that Broca’s area contains motor memories—in particular, memories of the sequences of muscular movements that are needed to articulate words. Talking involves rapid movements of the tongue, lips, and jaw, and these movements must be coordinated with each other and with those of the vocal cords; thus, talking requires some very sophisticated motor control mechanisms.

- Obviously, circuits of neurons somewhere in our brain will, when properly activated, cause these sequences of movements to be executed. Because damage to the inferior caudal left frontal lobe (including Broca’s area) disrupts the ability to articulate words, this region is a likely candidate for the location of these “programs.” The fact that this region is directly connected to the part of the primary motor cortex that controls the muscles used for speech certainly supports this conclusion.

But the speech functions of the left frontal lobe include more than programming the movements used to speak.

Broca’s aphasia is much more than a deficit in pronouncing words.

In general, three major speech deficits are produced by lesions in and around Broca’s area: agrammatism, anomia, and articulation difficulties. Although most patients with Broca’s aphasia will have all of these deficits to some degree, their severity can vary considerably from person to person—presumably, because their brain lesions differ.

3. Speech Production and Comprehension: Brain Mechanisms

- Damage to a region of the inferior left frontal lobe (Broca’s area) disrupts the ability to speak; it causes Broca’s aphasia.

- This disorder is characterized by slow, laborious, and nonfluent speech.

- When trying to talk with patients who have Broca’s aphasia, most people find it hard to resist supplying words patients are obviously groping for.

- Although they often mispronounce words, the ones they manage to come out with are usually meaningful.

- The posterior part of the cerebral hemispheres has something to say, but the damage to the frontal lobe makes it difficult for the patients to express these thoughts.

4. Broka’s Aphasia

Broca’s aphasia: A form of aphasia characterized by agrammatism, anomia, and extreme difficulty in speech articulation.

- People with Broca’s aphasia find it easier to say some types of words than others. For example, they have great difficulty saying the little words with grammatical meaning, such as a, the, some, in, or about. These words are called function words , because they have important grammatical functions. The words that they do manage to say are almost entirely content words —words that convey meaning, including nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, such as apple, house, throw, or heavy.

Agrammatism

- One of the usual symptoms of Broca’s aphasia; a difficulty in comprehending or properly employing grammatical devices, such as verb endings and word order.

Anomia

- Difficulty in finding (remembering) appropriate word to describe an object, action, or attribute; one of the symptoms of aphasia.

Function word

- A preposition, article, or other word that conveys little of the meaning of a sentence but is important in specifying its grammatical structure.

Content word

- A noun, verb, adjective, or adverb that conveys meaning.

Sample

- The drawing of the kitchen story is part of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Test.

The patient will say:

- kid . . . kk . . . can . . . candy . . . cookie . . . candy . . . well I don’t know but it’s writ . . . easy does it . . . slam . . . early . . . fall . . . men . . . many no . . . girl. Dishes . . . soap . . . soap . . . water . . . water . . . falling pah that’s all . . . dish . . . that’s all.

Cookies . . . can . . . candy . . . cookies cookies . . . he . . . down . . . That’s all. Girl . . . slipping water . . . water . . . and it hurts . . . much to do . . . Her . . . clean up . . . Dishes . . . up there . . . I think that’s doing it.- Here is a sample of speech from a man with Broca’s aphasia, who is trying to describe a scene. As you will see, his words are meaningful, but what he says is certainly not grammatical. The dots indicate long pauses.

Speech Comprehension

So far, we described Broca’s aphasia as a disorder in speech production.

In an ordinary conversation Broca’s aphasics seem to understand everything that is said to them. They appear to be irritated and annoyed by their inability to express their thoughts well, and they often make gestures to supplement their scanty speech.

- The striking disparity between their speech and their comprehension often leads people to assume that their comprehension is normal. But it is not.

People with Broca’s aphasia can comprehend speech much better than they can produce it.

In fact, some observers have said that their comprehension is unimpaired, but as we will see, this is not quite true.

Comprehension of speech obviously begins in the auditory system, which detects and analyzes sounds.

- But recognizing words is one thing; comprehending them—understanding their meaning—is another

- Recognizing a spoken word is a complex perceptual task that relies on memories of sequences of sounds.

- This task appears to be accomplished by neural circuits in the superior temporal gyrus of the left hemisphere, a region that has come to be known as Wernicke’s area.

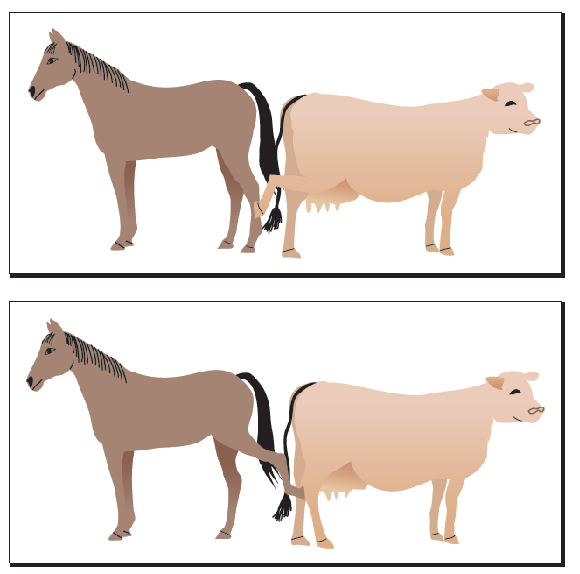

1. Assessment of Grammatical Ability

- This is an example of the stimuli used in the experiment by Schwartz, Saffran, and Marin (1980).

Schwartz, Saffran, and Marin (1980) showed Broca’s aphasics pairs of pictures in which agents and objects of the action were reversed: for example, a horse kicking a cow and a cow kicking a horse, a truck pulling a car and a car pulling a truck, and a dancer applauding a clown and a clown applauding a dancer. As they showed each pair of pictures, they read the subject a sentence, for example, The horse kicks the cow.

The subjects’ task was to point to the appropriate picture, indicating whether they understood the grammatical construction of the sentence. They performed very poorly.

2. Wernicke’s Aphasia

A region of auditory association cortex on the left temporal lobe of humans, which is important in the comprehension of words and the production of meaningful speech.

Wernicke’s Aphasia

- The primary characteristics of Wernicke’s aphasia are poor speech comprehension and production of meaningless speech.

- Unlike Broca’s aphasia, Wernicke’s aphasia is fluent and unlabored; the person does not strain to articulate words and does not appear to be searching for them.

- Because the superior temporal gyrus is a region of auditory association cortex and because a comprehension deficit is so prominent in Wernicke’s aphasia, this disorder has been characterized as a receptive aphasia.

Wernicke’s aphasia, like Broca’s aphasia, actually appears to consist of several deficits.

- The abilities that are disrupted include

- recognition of spoken words

- the ability to convert thoughts into words

Recognition: Pure Word Deafness

Recognizing a word is not the same as comprehending it. If you hear a foreign word several times, you will learn to recognize it; however, unless someone tells you what it means, you will not comprehend it. Recognition is a perceptual task; comprehension involves retrieval of additional information from memory.

- Damage to the left temporal lobe can produce a disorder of auditory word recognition, uncontaminated by other problems. This syndrome is called pure word deafness.

More significantly, their own speech is unimpaired. They can often understand what other people are saying by reading their lips. They can also read and write, and they sometimes ask people to communicate with them in writing. Clearly, pure word deafness is not an inability to comprehend the meaning of words; if it were, people with this disorder would not be able to read people’s lips or read words written on paper.

Functional imaging studies confirm that perception of speech sounds activates neurons in the auditory association cortex of the superior temporal gyrus (Scott et al., 2000).

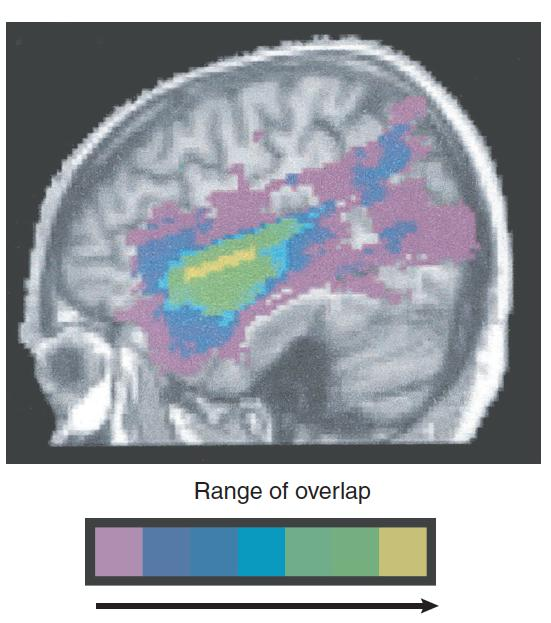

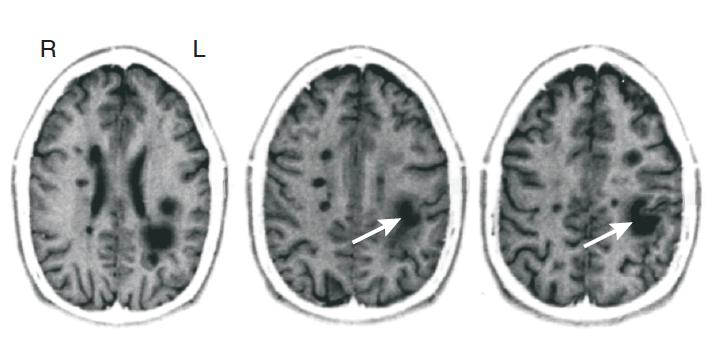

- Pure Word Deafness

- An MRI scan shows the damage to the superior temporal lobe of a patient with pure word deafness (arrow)

- The scan shows the overlap in the lesions of nine patients with deficits of speech comprehension. Note the similarity of the region of greatest overlap (yellow and green) with the damaged region shown on the left

Apparently, two types of brain injury can cause pure word deafness: disruption of auditory input to the superior temporal cortex or damage to the superior temporal cortex itself (Poeppel, 2001; Stefanatos, Gershkoff, and Madigan, 2005).

Either type of damage disturbs the analysis of the sounds of words and hence prevents people from recognizing other people’s speech

Mirror Neurons and Speech

Our brains contain circuits of mirror neurons—neurons activated either when we perform an action or see another person performing particular grasping, holding, or manipulating movements, or when we perform these movements ourselves (Gallese et al., 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 2001).

Feedback from these neurons may help us to understand the intent of the actions of others.

Although speech recognition is clearly an auditory event, research indicates that hearing words automatically engages brain mechanisms that control speech. In other words, these mechanisms appear to contain mirror neurons that are activated by the sounds of words.

For example, Fridriksson et al. (2008) found that when people watched (but did not hear) other people making speech movements, the temporal (auditory) and frontal (motor) cortical language areas were activated. These regions were not activated when the subjects watched people making nonspeech movements with their mouths.

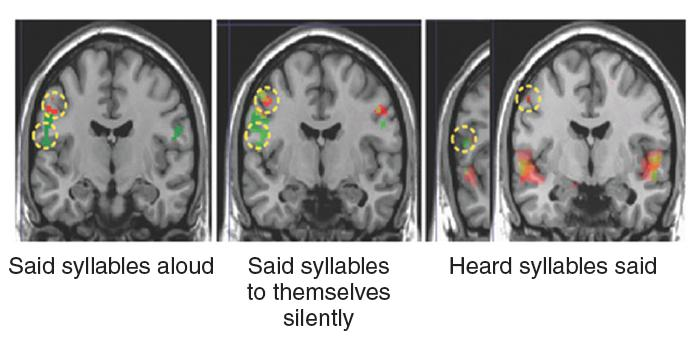

- As this figure shows, in all three conditions, regions of brain involved with lip movements (green) and tongue movements (red) were activated

- Speaking, watching other people speak, thinking about speaking, and listening to speech sounds all activate brain regions involved in language, which suggests that circuits of mirror neurons play role in speech comprehension

Brain activation in the primary motor cortex that occurred when people said syllables aloud, said syllables to themselves silently, or heard someone else saying syllables. The two regions marked with yellow circles are involved in the control of tongue movements (syllables that included the sound of t, shown in green) and lip movements (syllables that included the sound of p, shown in red).

Deficits

The abilities that are disrupted include

- recognition of spoken words (pure word deafness, Wernicke’s area)

- comprehension of the meaning of words (Transcortical Sensory Aphasia)

- the ability to convert thoughts into words (Transcortical Sensory Aphasia)

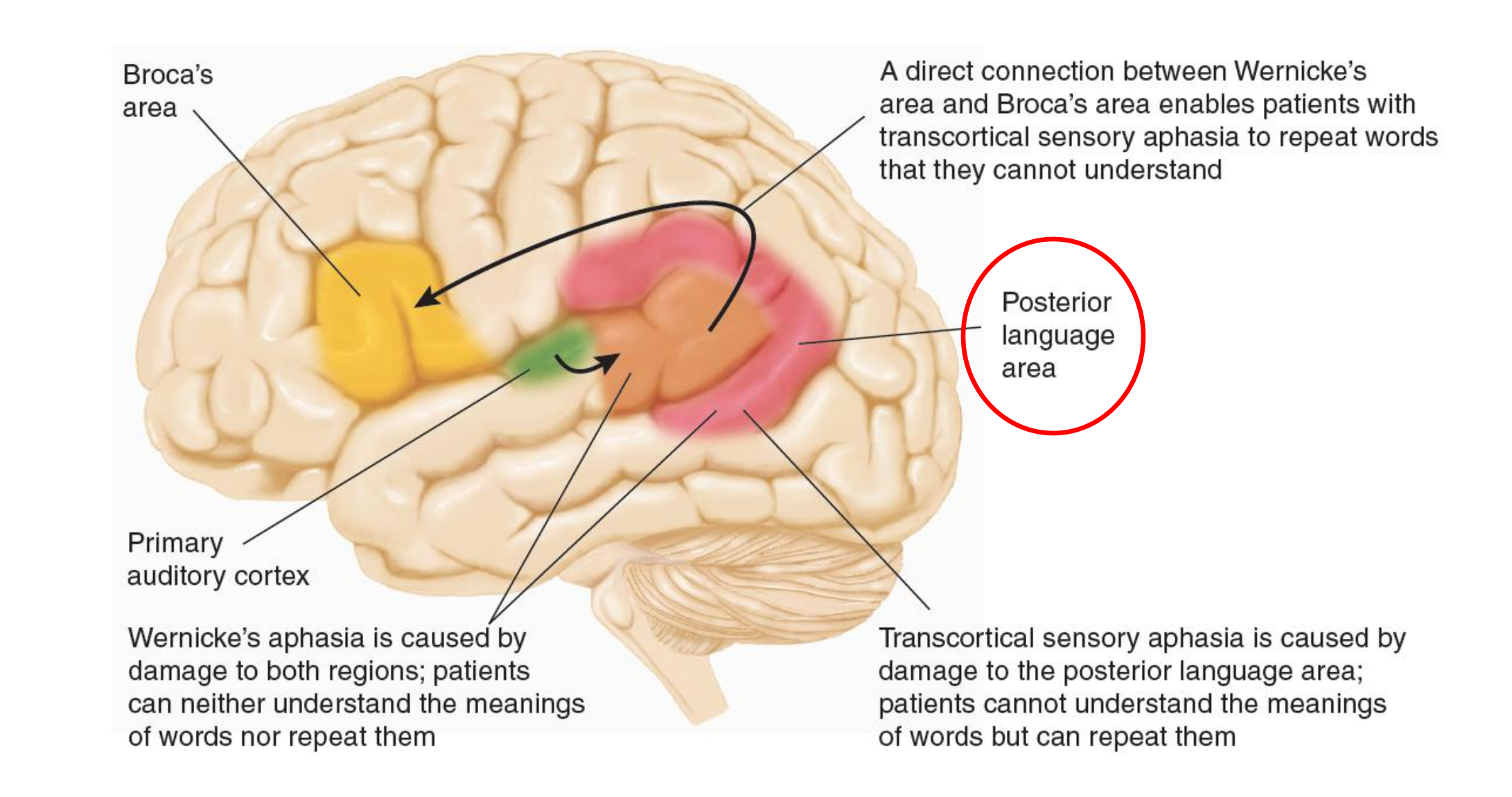

3. Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

- Failure to (Deficit 2) comprehend the meaning of words, and the (Deficit 3) inability to express thoughts in meaningful speech, appear to be produced by damage that extends beyond Wernicke’s area into the region that surrounds the posterior part of the lateral fissure, near the junction of the temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes.

- This region is referred to as the posterior language area.

- This schematic diagram shows the location and interconnections of the posterior language area and an explanation of its role in transcortical sensory aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia

- The symptoms of Wernicke’s aphasia consist of those of pure word deafness plus those of transcortical sensory aphasia

(1) Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

Wernicke’s area is involved in the analysis of speech sounds and in the recognition of words.

The posterior language area appears to serve as a place for interchanging information between the auditory representation of words and the meanings of these words, stored as memories in the rest of the sensory association cortex.

Damage to the posterior language area alone, which isolates Wernicke’s area, produces a disorder known as transcortical sensory aphasia.

- Damage to the posterior language area does not disrupt people’s ability to recognize words, but it does disrupt their ability to understand words or to produce meaningful speech of their own.

Transcortical sensory aphasia

- A speech disorder in which a person has difficulty comprehending speech and producing meaningful spontaneous speech but can repeat speech; caused by damage to posterior language area (the region of the brain posterior to Wernicke’s area).

The difference between transcortical sensory aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia is that patients with transcortical sensory aphasia can repeat what other people say to them; therefore, they can recognize words.

However, they cannot comprehend the meaning of what they hear and repeat; nor can they produce meaningful speech of their own.

(2) A Case of Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

Geschwind, Quadfasel, and Segarra (1968) described a particularly interesting case of transcortical sensory aphasia. A woman sustained extensive brain damage from carbon monoxide produced by a faulty water heater. She spent several years in the hospital before she died, without ever saying anything meaningful on her own. She did not follow verbal commands or otherwise give signs of understanding them. However, she often repeated what was said to her.

For example, if an examiner said “Please raise your right hand,” she would reply “Please raise your right hand.” The repetition was not parrotlike; she did not imitate accents different from her own, and if someone made a grammatical error while saying something to her, she sometimes repeated the sentence correctly, without the error. She could also recite poems if someone started them. For example, when an examiner said, “Roses are red, violets are blue,” she continued with “Sugar is sweet and so are you.” She could sing and would do so when someone started singing a song she knew. She even learned new songs from the radio while in the hospital. Remember, though, that she gave no signs of understanding anything she heard or said. This disorder, along with pure word deafness, clearly confirms the conclusion that recognizing spoken words and comprehending them are different processes and involve different brain mechanisms.

4. What is the meaning

Words refer to objects, actions, or relationships in the world. Thus, the meaning of a word is defined by particular memories associated with it.

- For example, knowing the meaning of the word tree means being able to imagine the physical characteristics of trees: what they look like, what the wind sounds like blowing through their leaves, what the bark feels like, and so on. It also means knowing facts about trees: about their roots, buds, flowers, nuts, and wood and the chlorophyll in their leaves.

- Action words such as throw involve memories of seeing someone throwing something, and also involve imagining what it feels like to throw something yourself. These memories are stored not in the primary speech areas but in other parts of the brain, especially regions of the association cortex.

Different categories of memories may be stored in particular regions of the brain, but they are somehow tied together, so hearing the word tree or throw activates all of them. the hippocampal formation is involved in this process of tying related memories together.)

The brain’s verbal mechanisms are involved in recognizing words and comprehending their meaning.

- The concept of a dictionary serves as a useful analogy. Dictionaries contain entries (the words) and definitions (the meanings of the words).

In the brain we have at least two types of entries: auditory and visual. That is, we can look up a word according to how it sounds or how it looks (in writing). Let us consider just one type of entry: the sound of a word. We hear a familiar word and understand its meaning. How do we do so?

- First, we must recognize the sequence of sounds that constitute the word—We find the auditory entry for the word in our “dictionary.” As we saw, this entry appears in Wernicke’s area.

- Next, the memories that constitute the meaning of the word must be activated. Presumably, Wernicke’s area is connected—through the posterior language area—with the neural circuits that contain these memories.

The “Dictionary” in the Brain

Wernicke’s area contains the auditory entries of words; the meanings are contained as memories in the sensory association areas.

(1) Evaluating Metaphors (隐喻)

- These images of neural activity in the right hemisphere were produced when the subjects evaluated the meaning of metaphors.

Functional imaging studies confirm these observations. Nichelli et al. (1995) found that judging the moral of Aesop’s fables (as opposed to judging more superficial aspects of the stories) activated regions of the right hemisphere

Sotillo et al. (2005) found that a task that required comprehension of metaphors such as “green lung of the city” (that is, a park) activated the right superior temporal cortex.

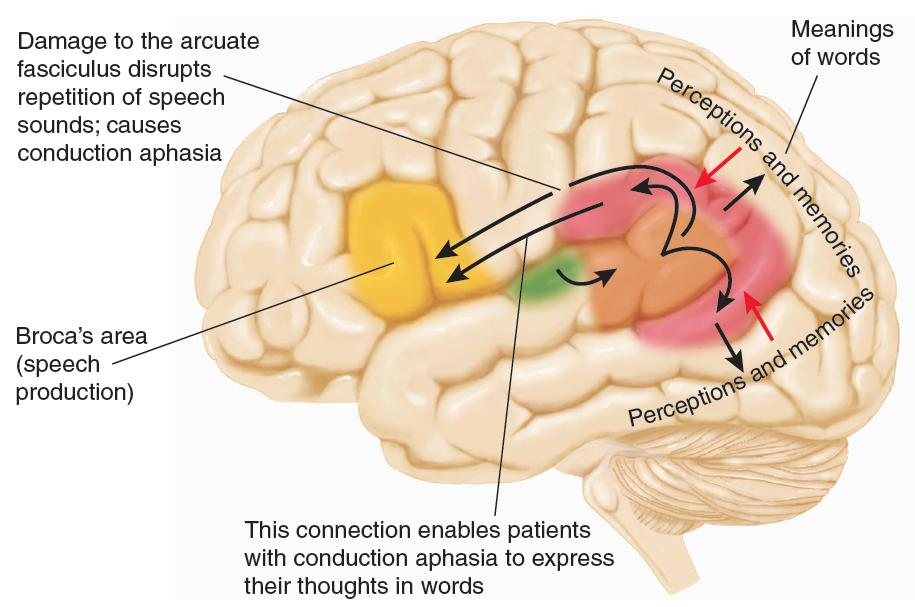

Repetition: Conduction Aphasia

Repetition: Conduction aphasia

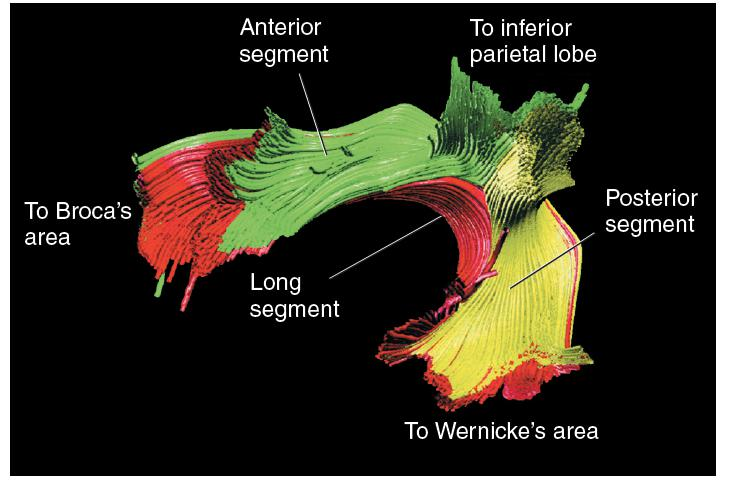

- People with transcortical sensory aphasia can repeat (speak) what they hear (recognize) which suggests that there is a direct connection between Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area—and there is: the arcuate fasciculus (“arch-shaped bundle”).

- Conduction aphasia : An aphasia characterized by inability to repeat words that are heard but the ability to speak normally and comprehend the speech of others.

Arcuate fasciculus

- A bundle of axons that connects Wernicke’s area with Broca’s area; damage causes conduction aphasia

- This bundle of axons is found in the human brain, but is absent or much smaller in the brains of nonhuman primates. The arcuate fasciculus appears to convey information about the sounds of words but not their meanings.

- MRI scans show the subcortical damage responsible for a case of conduction aphasia. This lesion damaged the arcuate fasciculus, a fiber bundle connecting Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area.

1. Components of the Arcuate Fasciculus

- A computer-generated reconstruction of the components of the arcuate fasciculus was obtained through diffusion tensor MRI.

A Hypothetical Explanation of Conduction Aphasia

- A lesion that damages the arcuate fasciculus disrupts transmission of auditory information, but not information related to meaning, to the frontal lobe

- Black arrows represent comprehension of words—the activation of memories that correspond to a word’s meaning. Red arrows represent translation of thoughts or perceptions into words.

Memory of Words: Anomic Aphasia

Anomia (命名不能), in one form or another, is a hallmark of aphasia. However, one category of aphasia consists of almost pure anomia, the other symptoms being inconsequential.

- Speech of patients with anomic aphasia is fluent and grammatical, and their comprehension is excellent, but they have difficulty finding the appropriate words. They often employ circumlocutions (literally, “speaking in a roundabout way”) to get around missing words.

Anomic aphasia is different from Wernicke’s aphasia

- People with anomic aphasia can understand what other people say, and what they say makes perfect sense, even if they often choose roundabout ways to say it.

Circumlocution

- A strategy by which people with anomia find alternative ways to say something when they are unable to think of the most appropriate word.

1. A Case of Anomic Aphasia

- We asked her to describe the kitchen picture. Her pauses, which are marked with three dots, indicate word-finding difficulties. In some cases, when she could not find a word, she supplied a definition instead (a form of circumlocution) or went off on a new track. I have added the words in brackets that I think she intended to use.

- Examiner: Tell us about that picture.

- Patient: It’s a woman who has two children, a son and a daughter, and her son is to get into the . . . cupboard in the kitchen to get out [take] some . . . cookies out of the [cookie jar] . . . that she possibly had made, and consequently he’s slipping [falling] . . . the wrong direction [backward] . . . on the . . . what he’s standing on [stool], heading to the . . . the cupboard [floor] and if he falls backwards he could have some problems [get hurt], because that [the stool] is off balance.

2. Anomia for Words

Several studies have found that anomia for verbs (more correctly called averbia) is caused by damage to the frontal cortex, in and around Broca’s area (Damasio and Tranel, 1993; Daniele et al., 1994; Bak et al., 2001).

- If you think about it, that makes sense. The frontal lobes are devoted to planning, organizing, and executing actions, so it should not surprise us that they are involved in the task of remembering the names of actions.

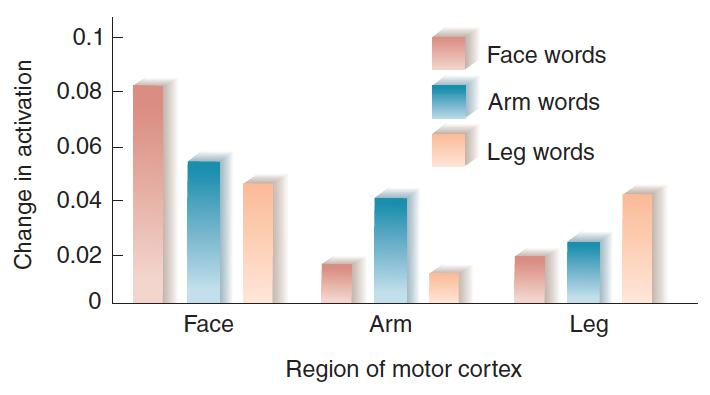

Hauk, Johnsrued, and Pulvermüller (2004) had subjects read verbs that related to movements of different parts of the body.

- For example, bite, slap, and kick involve movements of the face, arm, and leg, respectively.

- The investigators found that when the subjects read a verb, they saw activation in the regions of the motor cortex that controlled the relevant part of the body.

Verbs and Movements

- The figure shows the relative activation of regions of the motor cortex that control movements of the face, arm, and leg when people read verbs that describe movements of these regions, such as bite, slap, and kick

3. Aphasia in Deaf People

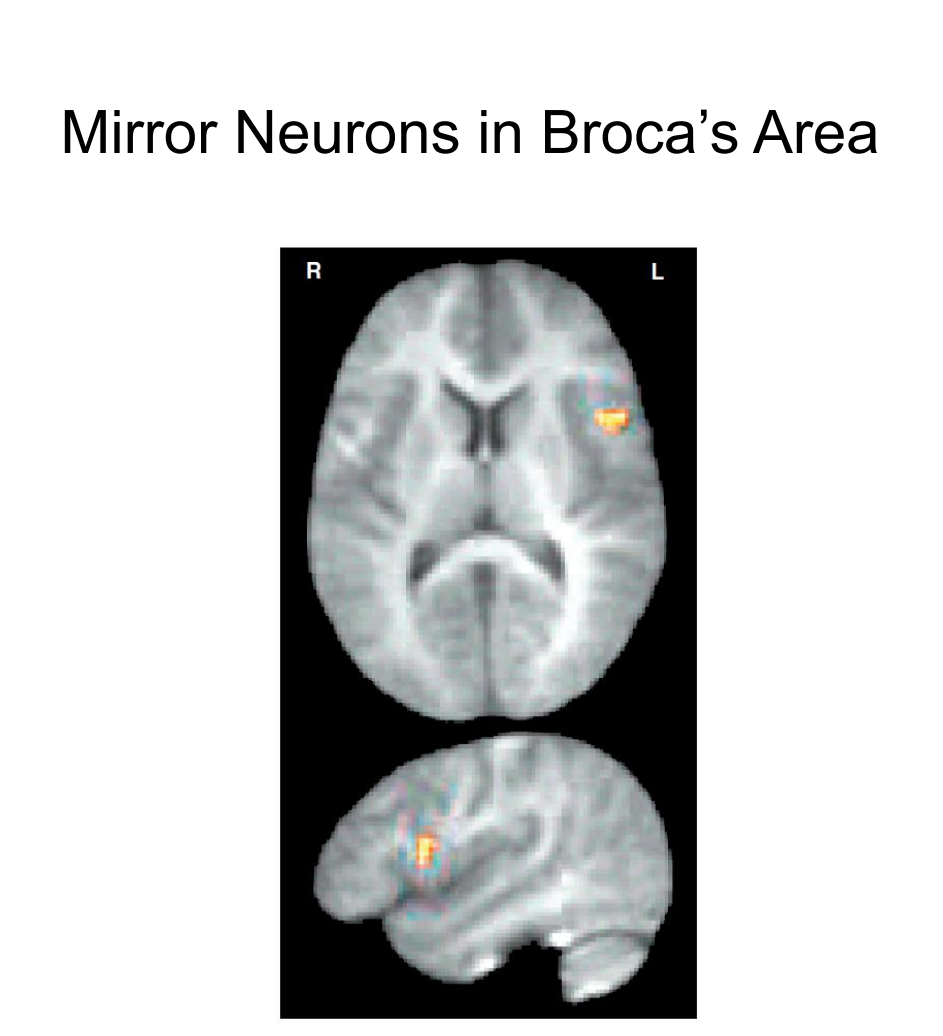

Mirror neurons become active when humans see or perform particular grasping, holding, or manipulating movements.

- Some of these neurons are found in Broca’s area. Presumably, these neurons play an important role in learning to mimic another people’s hand movements.

- Indeed, they might have been involved in the development of hand gestures used for communication in our ancestors, and they undoubtedly are used by deaf people when they communicate by sign language.

- A functional imaging study by Lacoboni et al. (1999) found that Broca’s area was activated when people observed and imitated finger movements.

- PET scans show a region of the inferior left frontal lobe that was activated when a person saw a finger movement or imitated it. Top: Horizontal section. Bottom: Lateral view of left hemisphere.

Several studies have found linkage between speech and hand movements, which supports the suggestion that the spoken language of present-day humans evolved from hand gestures.

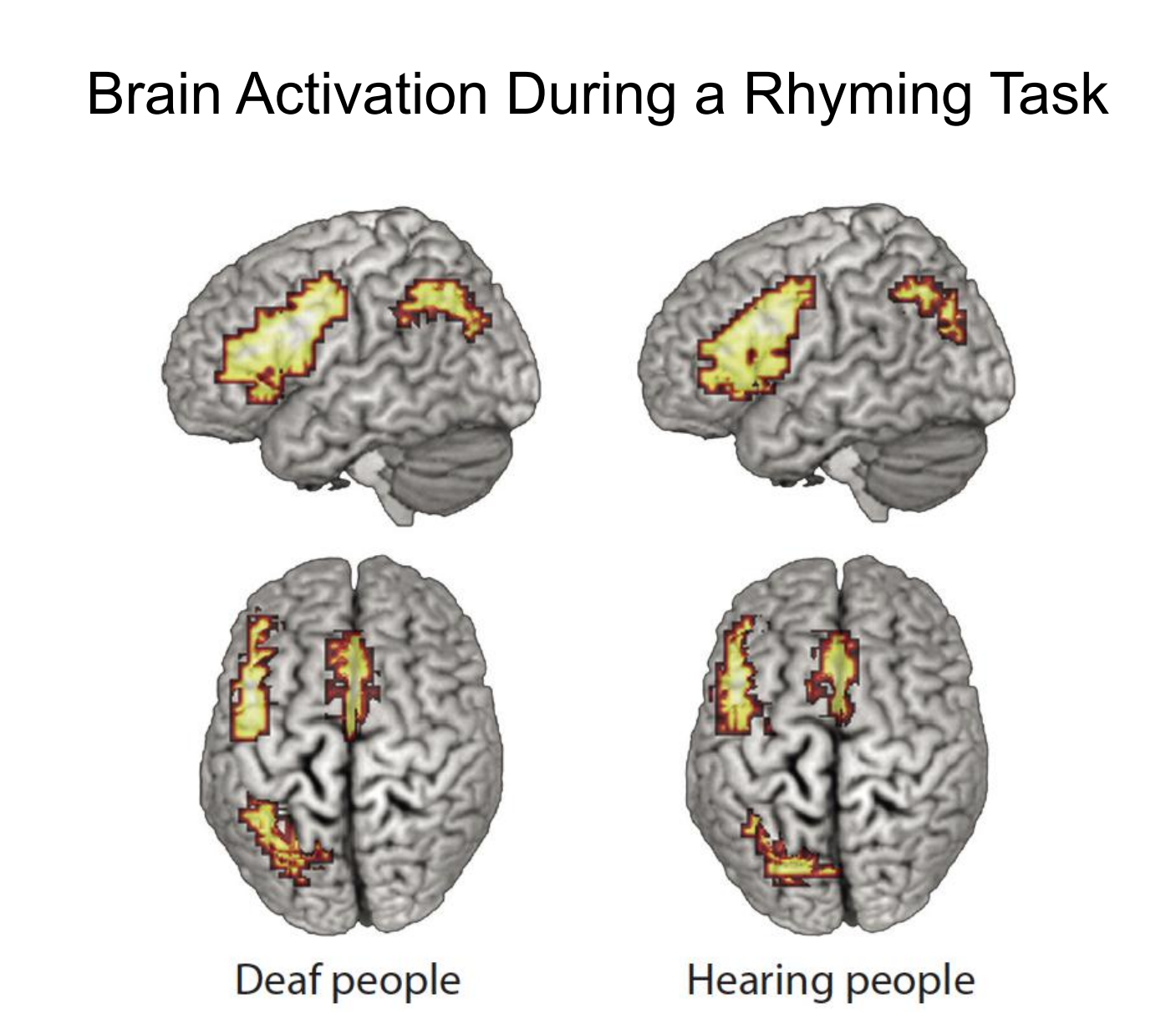

- As you might imagine, when a hearing person is asked to look at a pair of drawings and say whether the names of items show rhyme, functional imaging shows increased activation in the region of Broca’s area because the person “says” the two words subvocally.

- And if we ask deaf people who are able to talk to perform this task, the same region is activated (MacSweeney et al. 2008b).

- The same language-related regions of the brain are activated by deaf and hearing people when they decide whether two written words rhyme.

四、Prosody: Rhythm, Tone, and Emphasis in Speech

Our speech has a regular rhythm and cadence: we give some words stress (that is, we pronounce them louder), and we vary the pitch of our voice to indicate phrasing and to distinguish between assertions and questions.

- In addition, we can impart information about our emotional state through the rhythm, emphasis, and tone of our speech.

- These rhythmic, emphatic, and melodic aspects of speech are referred to as prosody(韵律).

Prosody

- The use of changes in intonation and emphasis to convey meaning in speech besides that specified by the particular words; an important means of communication of emotion.

Evidence from studies of normal people and patients with brain lesions suggests that prosody is a special function of right hemisphere.

This function is undoubtedly related to the more general role of this hemisphere in musical skills and expression and recognition of emotions: Production of prosody is rather like singing, and prosody often serves as vehicle for conveying emotion.

- Functional MRI scans were made while subjects listened to normal speech (blue and green regions) or the prosodic elements of speech (orange and yellow regions).

- Meaningful components of speech primarily activated the left hemisphere (blue and green regions), whereas the prosodic components primarily activated the right hemisphere (orange and yellow regions).

Recognition of People’s Voices

People learn at an early age to recognize the voices of particular individuals.

Even newborn infants can recognize the voices of their parents, which they apparently learned while they were still in their mother’s uterus (Ockleford et al., 1988).

Some people with localized brain damage have great difficulty recognizing voices—a disorder known as phonagnosia(语音失认症).

- [Comparing to prosopagnosia(面孔失认症)]

Most cases of phonagnosia are caused by brain damage.

- Recognition of a particular voice is independent of the recognition of words and their meanings.

- Some people have lost the ability to understand words but can still recognize voices, while others display the opposite deficits (Belin, Fecteau, and Bédard 2004).

- Functional imaging studies have implicated the right anterior superior temporal cortex in voice recognition.

- For example, von Kriegstein et al. (2003) found that this region was activated by a task that required subjects to recognize particular voices but not particular words.

1. Stuttering

- Stuttering is a speech disorder characterized by frequent pauses, prolongations of sounds, or repetitions of sounds, syllables, or words that disrupt the normal flow of speech.

- Stuttering, which appears to be influenced by genetic factors, affects approximately 1 percent of population and is three times more prevalent in men than in women (Brown et al. 2005; Fisher 2010).

Stuttering is not a result of abnormalities in the neural circuits that contain the motor programs for speech.

- For example, stuttering is reduced or eliminated when a person reads aloud with another speaker, sings, or reads in cadence with a rhythmic stimulus.

- Neumann et al. (2005) provide further evidence that the apparently abnormal auditory feedback in stutterers is reflected in decreased activation of their temporal cortex.

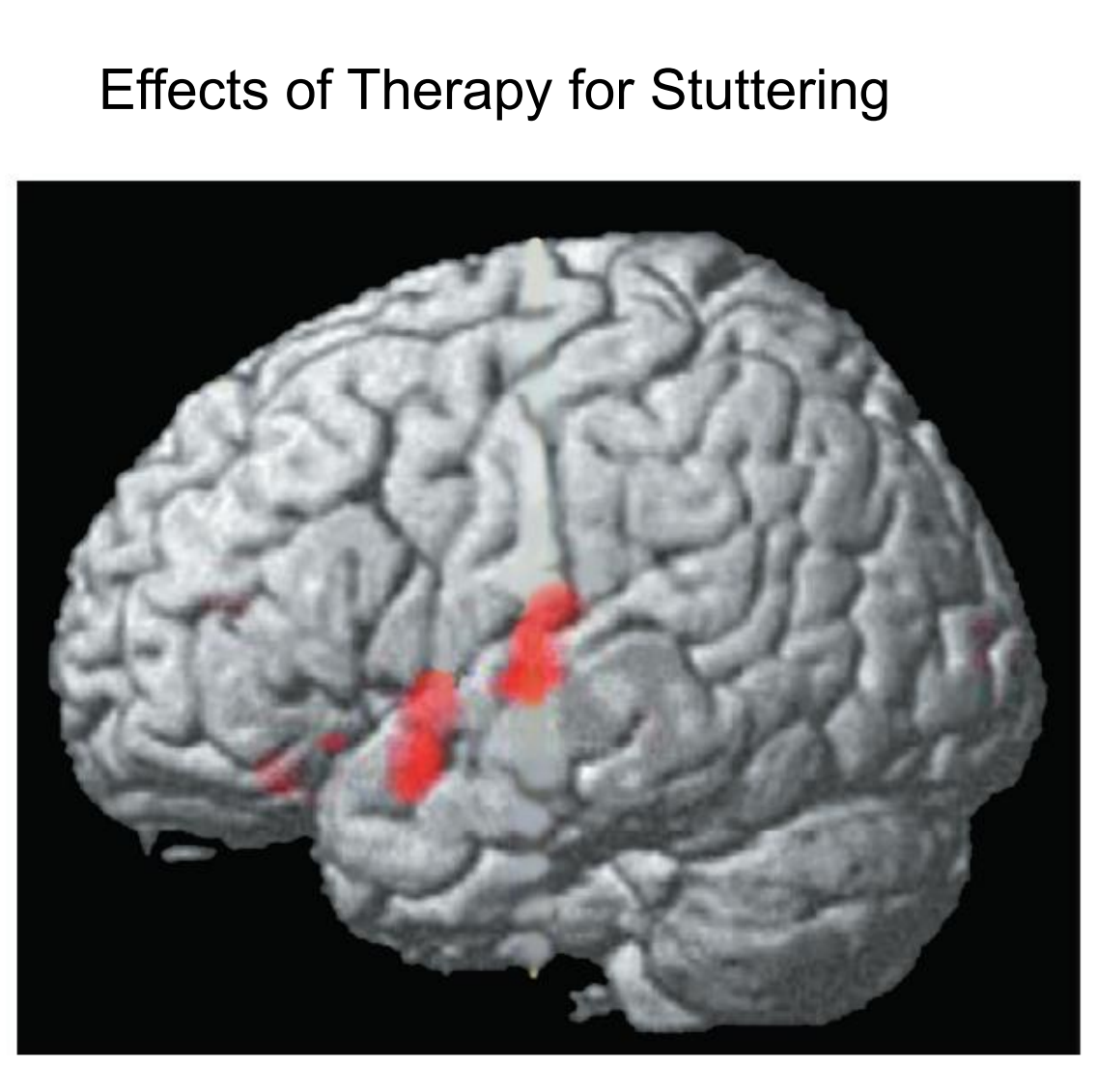

- A functional MRI scan shows regions of the superior temporal lobe that showed increased activity one year after a successful course of therapy for stuttering.

The authors used fMRI to measure the regional brain activation of stutterers reading sentences aloud during two sessions, one before and one after a successful twelve-week course of fluency shaping therapy.

This figure shows that after the therapy, the activation of the temporal lobe–a region that Brown et al. (2005) found to show decreased activation–was increased.

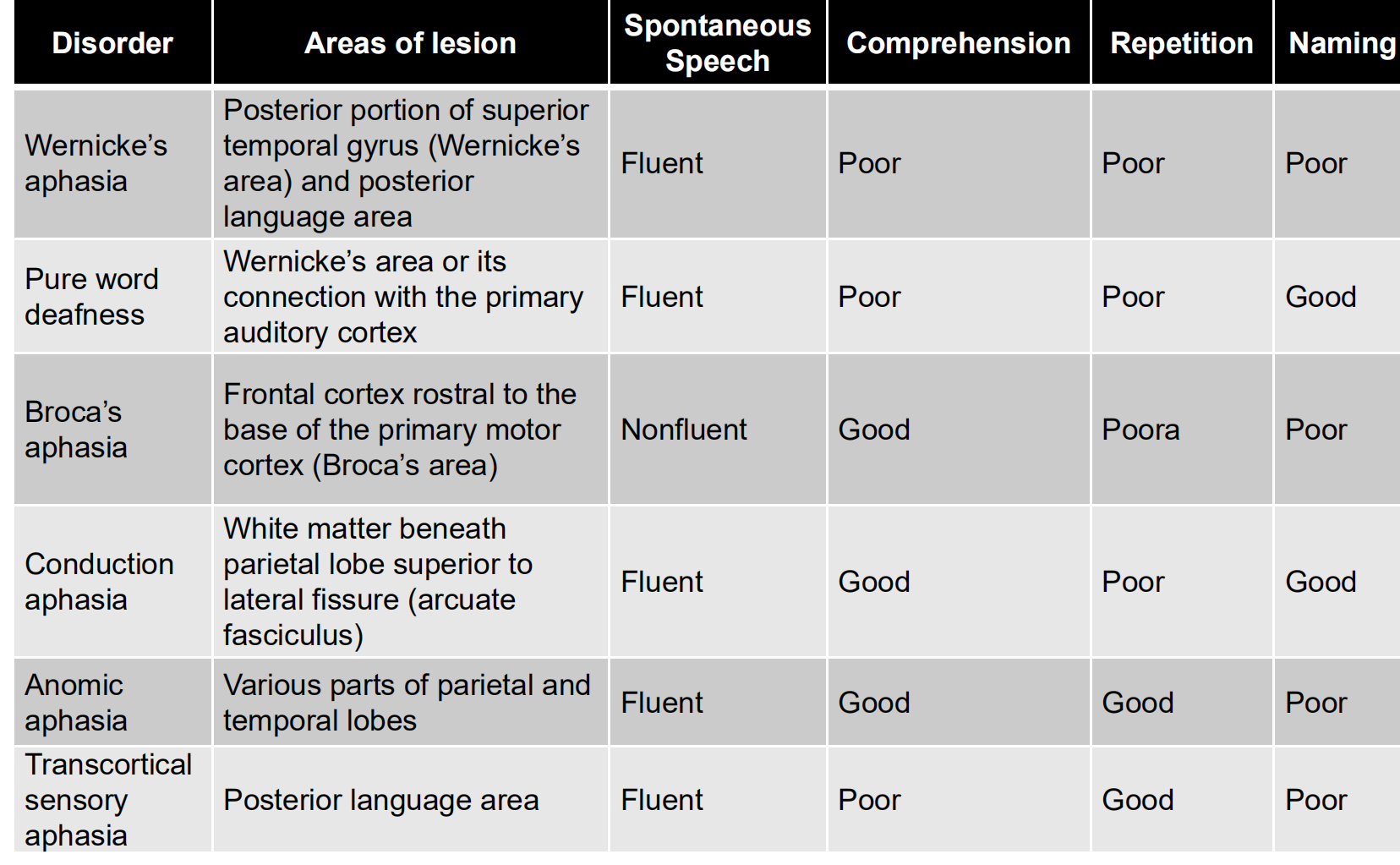

2. Aphasic Syndromes Produced by Brain Damage

| Disorder | Areas of lesion | Spontaneous Speech | Comprehension | Repetition | Naming |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wernicke’s aphasia | Posterior portion of superior temporal gyrus (Wernicke’s area) and posterior language area | Fluent | Poor | Poor | Poor |

| Pure word deafness | Wernicke’s area or its connection with the primary auditory cortex | Fluent | Poor | Poor | Good |

| Broca’s aphasia | Frontal cortex rostral to the base of the primary motor cortex (Broca’s area) | Nonfluent | Good | Poor | Poor |

| Conduction aphasia | White matter beneath parietal lobe superior to lateral fissure (arcuate fasciculus) | Fluent | Good | Poor | Good |

| Anomic aphasia | Various parts of parietal and temporal lobes | Fluent | Good | Good | Poor |

| Transcorticalsensory aphasia | Posterior language area | Fluent | Poor | Good | Poor |

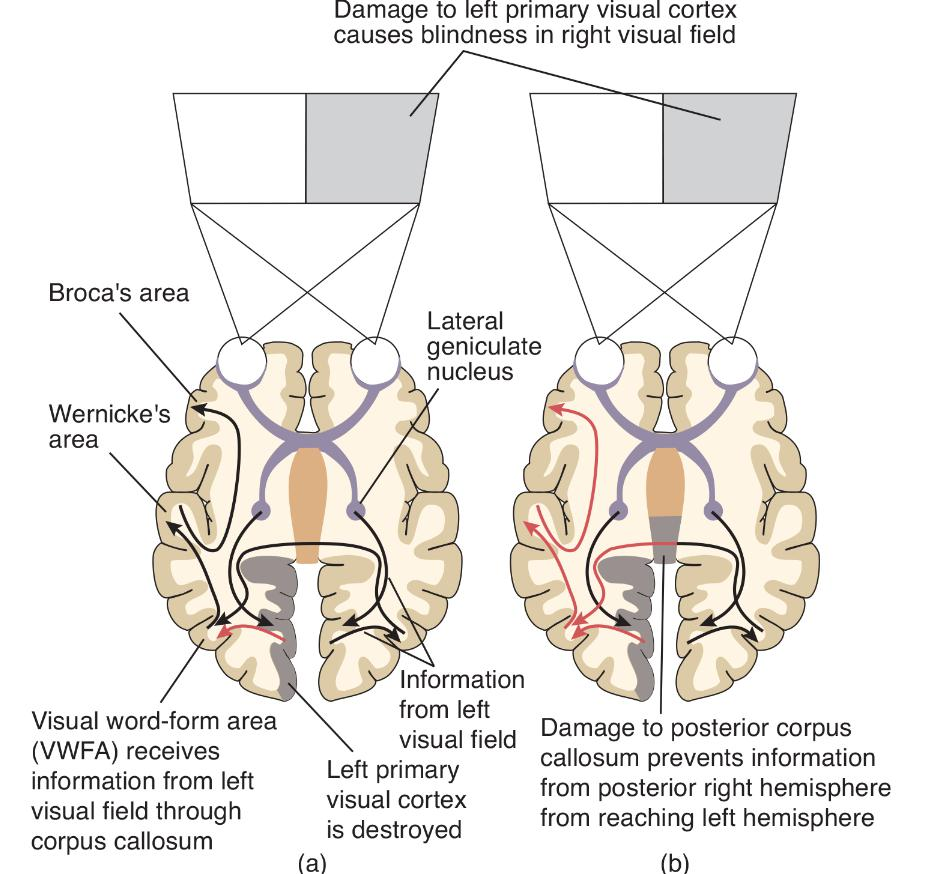

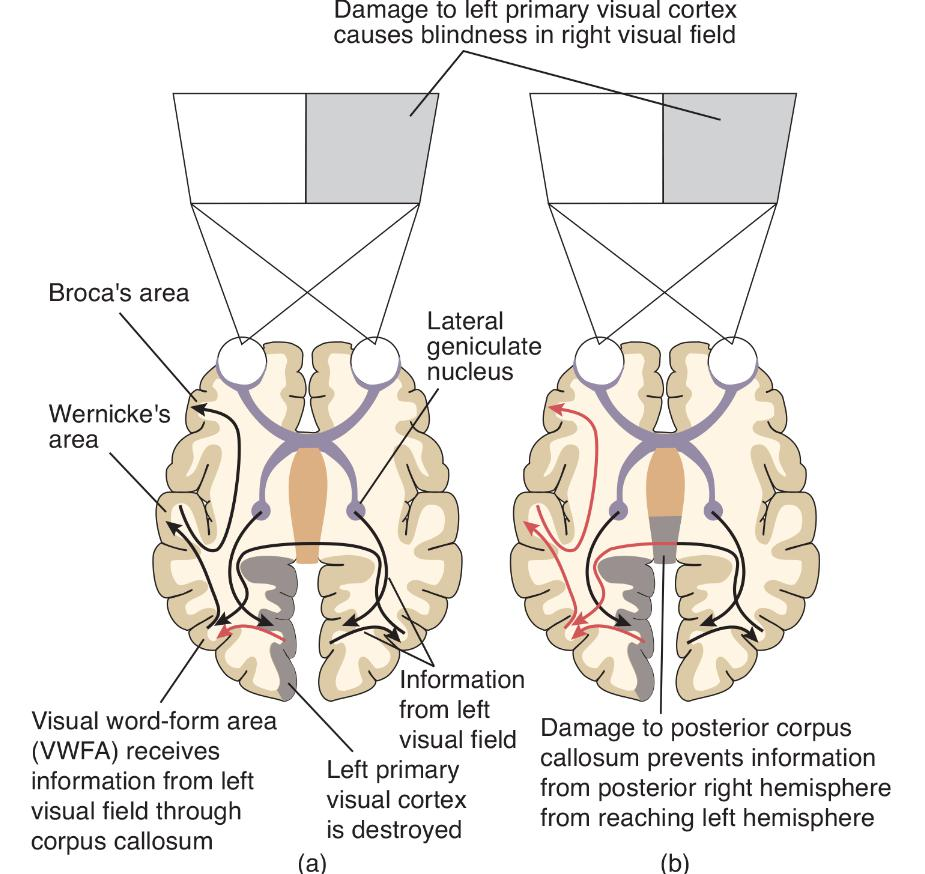

五、Disorders of Reading and Writing: Pure Alexia

Dejerine (1892) described a remarkable syndrome, which we now call pure alexia(纯失读), or sometimes pure word blindness or alexia without agraphia (失写).

His patient had a lesion in the visual cortex of the left occipital lobe and the posterior end of the corpus callosum.

The patient could still write, although he had lost the ability to read.

Pure alexia: Loss of the ability to read without loss of the ability to write; produced by brain damage.

- The disorder is caused by lesions that prevent visual information from reaching the visual association cortex of the left hemisphere.

- In this schematic diagram, red arrows indicate the flow of information that has been interrupted by brain damage.

- (a) The route followed by information as a person with damage to the left primary visual cortex reads aloud.

- (b) Additional damage to the posterior corpus callosum interrupts the flow of information and produces pure alexia.

Information from the left side of the visual field is transmitted to right striate cortex (primary visual cortex) and then to regions of right visual association cortex.

- From there, information crosses the posterior corpus callosum and is transmitted to a region of the left visual association cortex known as the visual word-form area (VWFA), where it is analyzed further.

- The information is then transmitted to speech mechanisms located in the left frontal lobe. Thus, the person can read the words aloud.

(b) The second diagram shows Dejerine’s patient. Notice how the additional lesion of the corpus callosum prevents visual information concerning written text from reaching the VWFA in the left hemisphere.

Because this brain region is essential for the ability to recognize words, the patient cannot read.

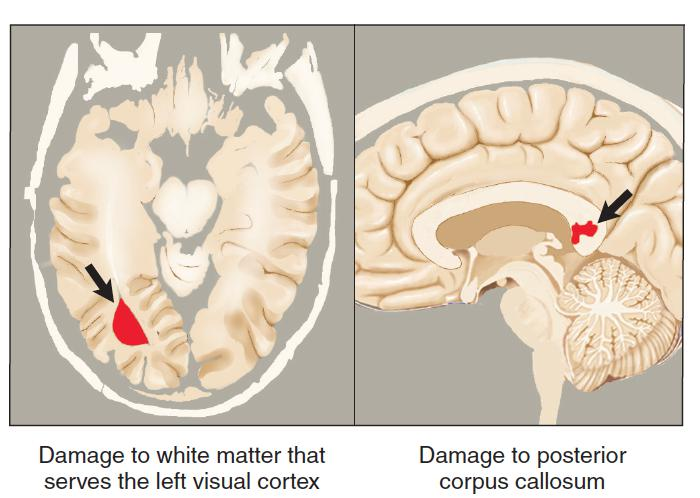

Pure Alexia in a Patient with Multiple Sclerosis

- Mao-Draayer and Panitch (2004) reported the case of a man with multiple sclerosis who displayed the symptoms of pure alexia after sustaining a lesion that damaged both the subcortical white matter of the left occipital lobe and the posterior corpus callosum.

- As you can see in this figure the lesions are in precisely the locations that Dejerine predicted would cause this syndrome, except that the white matter that serves the left primary visual cortex is damaged, not the cortex itself.

- The damage corresponds to that shown in Figure (b) .

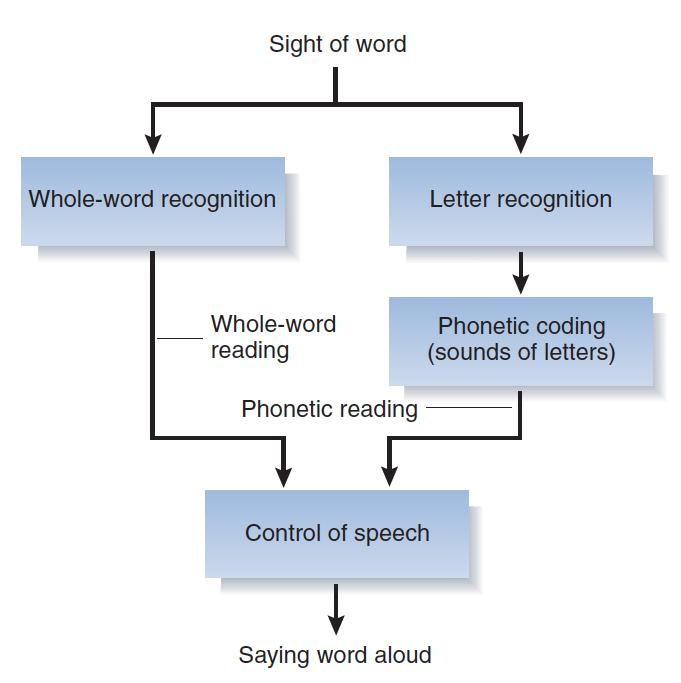

Toward an Understanding of Reading

Reading involves at least two different processes: direct recognition of the word as a whole and sounding it out letter by letter.

Whole-word reading

- Reading by recognizing a word as a whole; “sight reading.”

Phonetic reading

- Reading by decoding the phonetic significance of letter strings; “sound reading.”

Evidence for our ability to sound out words is easy to obtain. In fact, you can prove to yourself that phonetic reading exists by trying to read the following words:

- glab trisk chint

They are not really words, you don’t have trouble pronouncing them. Obviously, you did not recognize them, because you probably never saw them before. Therefore, you had to use what you know about the sounds that are represented by particular letters (or small groups of letters, such as ch) to figure out how to pronounce the words.

Model of the Reading Process

- This figure illustrates some elements of the reading processes.

- The diagram is an oversimplification of a very complex process, but it helps to organize some of the facts that investigators have obtained.

- If we see an unfamiliar word or a pronounceable nonword, we must try to read it phonetically.

In this simplified model, whole-word reading is used for most familiar words and phonetic reading is used for unfamiliar words and for nonwords such as glab, trisk, or chint.

The best evidence that proves that people can read words without sounding them out, using the whole-word method, comes from studies of patients with acquired dyslexias. Dyslexia means “faulty reading.”

Acquired dyslexias are those caused by damage to the brains of people who already know how to read. In contrast, developmental dyslexias refer to reading difficulties that become apparent when children are learning to read. Developmental dyslexias, which appear to involve anomalies in brain circuitry.

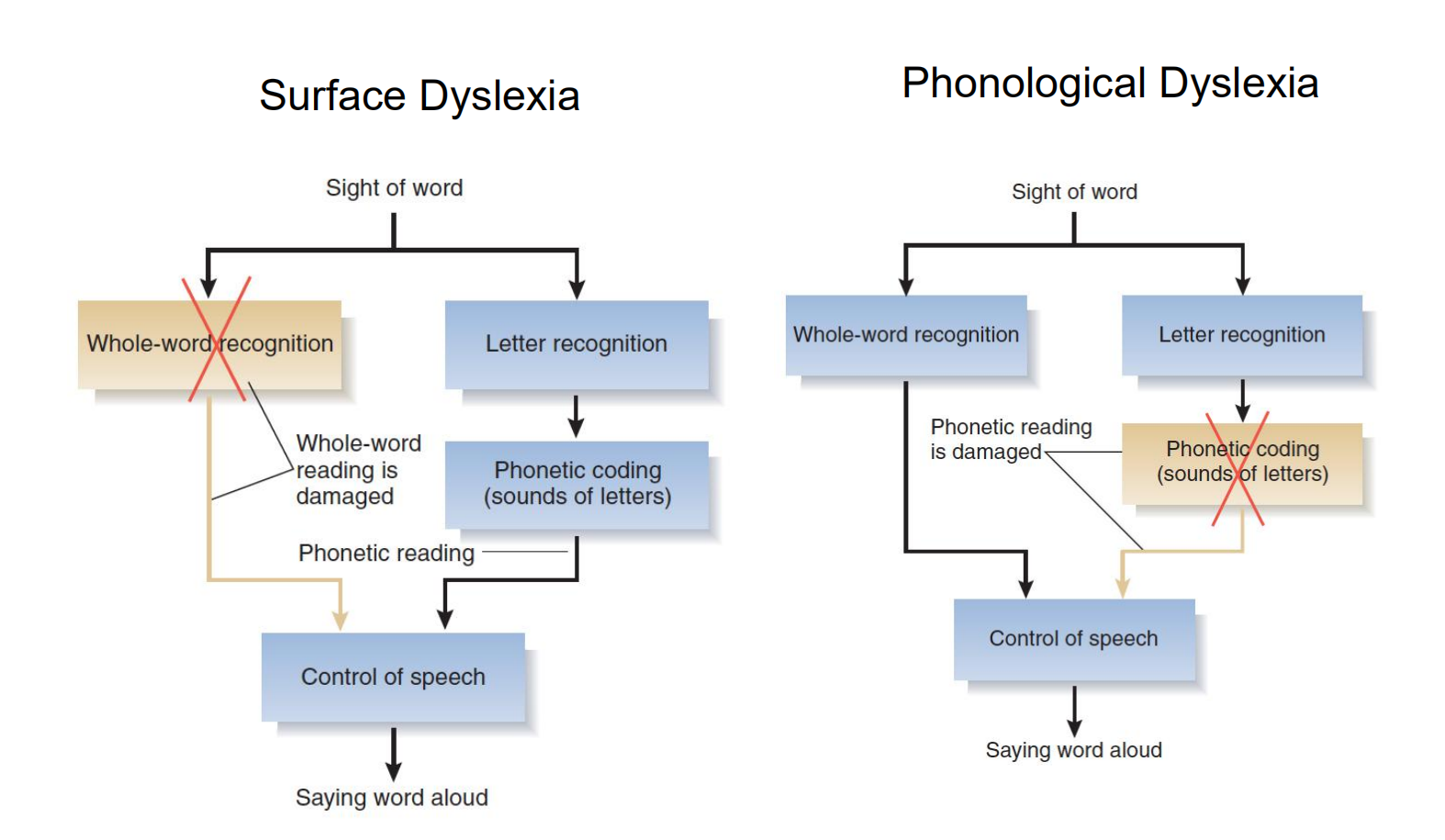

1. Types of Acquired Dyslexia

Investigators have reported several types of acquired dyslexias, and three of them are described in this section: surface dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, and direct dyslexia.

Surface dyslexia 表面性阅读困难

- A reading disorder in which a person can read words phonetically but has difficulty reading irregularly spelled words by the whole-word method.

- In this hypothetical example, whole-word reading is damaged; only phonetic reading remains.

Phonological dyslexia 音系性阅读障碍

- A reading disorder in which a person can read familiar words but has difficulty reading unfamiliar words or pronounceable nonwords.

- In this hypothetical example, phonetic reading is damaged; only whole-word reading remains.

Direct dyslexia 直接性阅读障碍

- A language disorder caused by brain damage in which the person can read words aloud without understanding them.

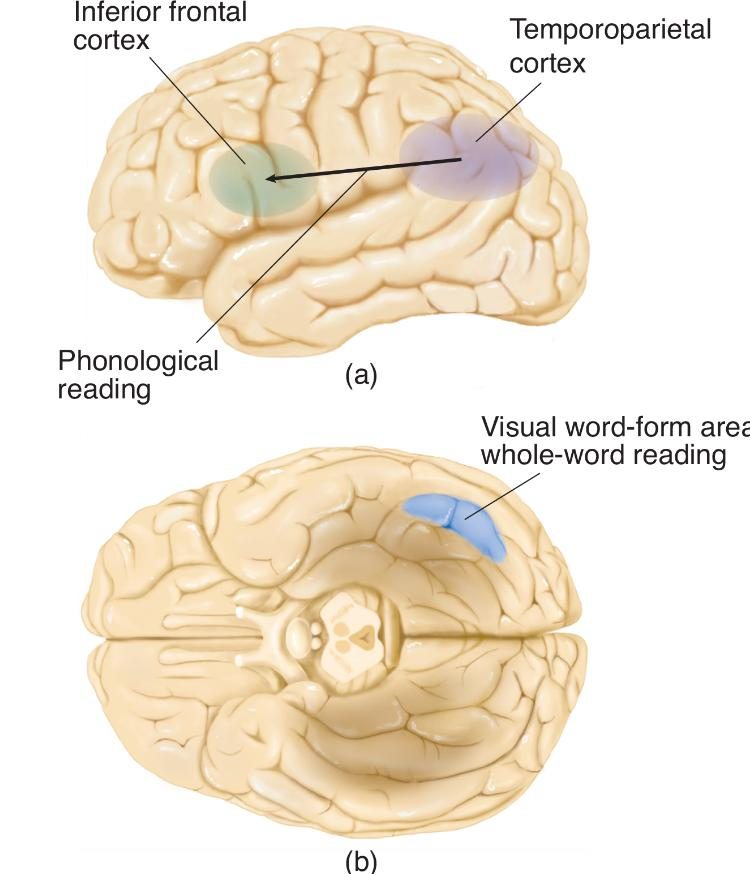

Evidence from lesion and functional imaging studies with readers of English, Chinese, and Japanese suggest that process of whole-word reading follows the ventral stream of the visual system to a region of the fusiform gyrus, located at the base of the temporal lobe.

- For example, functional imaging studies by Thuy et al. (2004) and Liu et al. (2008) found that reading of kanji words or Chinese characters (whole-word reading) activated the left fusiform gyrus.

- This region is known as visual word-form area (VWFA).

The Japanese language provides a particularly interesting distinction between phonetic and whole-word reading. The Japanese language makes use of two kinds of written symbols. Kanji symbols are pictographs, adopted from the Chinese language (although they are pronounced as Japanese words). Thus, they represent concepts by means of visual symbols but do not provide a guide to their pronunciation. Reading words expressed in kanji symbols is analogous, then, to whole-word reading. Kana symbols are phonetic representations of syllables; thus, they encode acoustical information. These symbols are used primarily to represent foreign words or Japanese words that the average reader would be unlikely to recognize if they were represented by their kanji symbols. Reading words expressed in kana symbols is obviously phonetic.

Studies of Japanese people with localized brain damage have shown that the reading of kana and kanji symbols involves different brain mechanisms (Iwata, 1984; Sakurai et al., 1994; Sakurai, Ichikawa, and Mannen, 2001). Difficulty reading kanji symbols is a form of surface dyslexia, whereas difficulty reading kana symbols is a form of phonological dyslexia. What regions are involved in these two kinds of reading?

2. Phonological and Whole-Word Reading

A schematic diagram showing the brain regions primarily involved in

- phonological reading

- whole-word reading

The fusiform face area of the right hemisphere has the ability to quickly recognize unique configurations of people’s eyes, noses, lips, and other features of their faces even when the differences between two people’s faces are very similar.

- For example, parents and close friends of identical twins can see at a glance which twin they are looking at.

Similarly, VWFA of left hemisphere can recognize word even if it closely resembles another one.

Subtle Differences in Written Words

- Unless you can read Arabic, Hindi, or Mandarin, you will probably have to examine these words carefully to find the small differences. However, as a reader of English, you will immediately recognize the words “car” and “ears.”

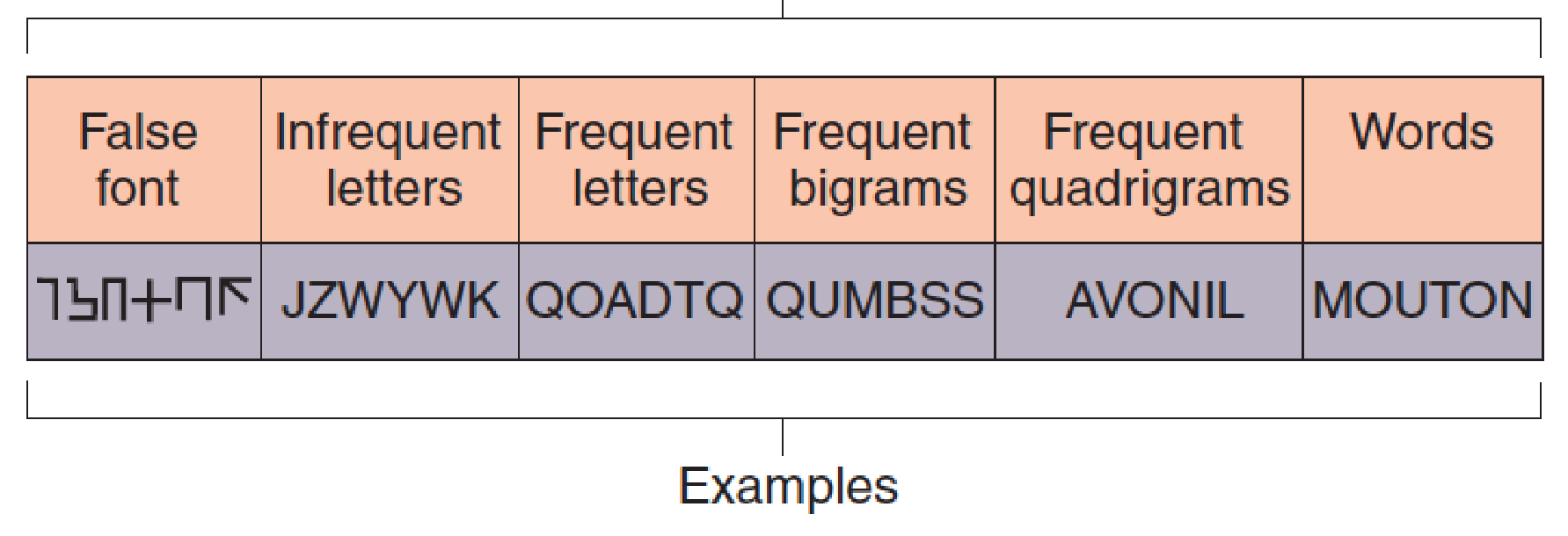

Vinckier and his colleagues had adult readers look at the following stimuli:

- strings of false fonts (nonsensical letter like symbols)

- strings of infrequent letters

- strings that contained infrequent bigrams

- strings that contained frequent bigrams

- strings that contained frequent quadrigrams

- real words

Stimuli Used in a Test of Word Recognition:

- These examples of stimuli were used in the experiment by Vinckier et al. (2007). Mouton is the French word for “sheep.” (The experiment took place in France.)

Effects of VWFA Lesion

- The scans show responses of brain regions to words, faces, houses, and tools before and after surgical removal of a small region of the VWFA. Note that the response to words (dark blue) is lost, but responses to faces, houses, and tools remains. The lesion is indicated by the green arrowheads.

Functional imaging showed that some brain regions were activated by all of the visual stimuli, including letter-like symbols, some were activated by letters but not symbols, and so on, up to regions that were activated by real words.

The most selective region included the left anterior fusiform cortex (the VWFA), which was activated only by actual words.

Many studies have found that damage to the VWFA produces surface dyslexia—that is, impairment of whole-word reading.

A study by Gaillard et al. (2006) combined fMRI and lesion evidence from a single subject that provides evidence that the left fusiform cortex does, indeed, contain this region.

Szwed et al. (2009) note that the most important cues to object recognition (which is the primary task of the visual system) are those that remain relatively constant even when we view objects from different angles.

The most reliable of these cues are ways that lines meet at vertices, forming junctions with particular shapes, such as L, T, and X.

Object and Word Recognition

- This figure shows a drawing and a word with the vertices missing. Can you figure out what they are?

- You will find them easier to recognize.

- I found it easier to recognize the drawing and word with the intact vertices (as I suspect you did)—and so did the subjects in the study by Szwed et al.

Recognizing a Spoken Word

Recognizing a spoken word is different from understanding it. For example, patients with transcortical sensory aphasia can repeat what is said to them even though they show no signs of understanding what they hear or say.

- The same is true for reading.

Direct dyslexia

- A language disorder caused by brain damage in which the person can read words aloud without understanding them.

Some children have great difficulty learning to read and never become fluent readers, even though they are otherwise intelligent.

Developmental dyslexia

Specific language learning disorders, called developmental dyslexias, tend to occur in families, a finding that suggests a genetic (and hence biological) component.

A reading difficulty in a person of normal intelligence and perceptual ability; of genetic origin or caused by prenatal or perinatal factors.

Writing depends on knowledge of words that are to be written, along with proper grammatical structure of sentences they are to form.

- Therefore, if a patient is unable to express himself or herself by speech, we should not be surprised to see a writing disturbance (dysgraphia)(书写困难) as well.

- In addition, most cases of dyslexia are accompanied by dysgraphia.

- Longcamp et al. (2005) found that simply looking at alphabetical characters activated the premotor cortex: on the left side in right-handed people and on the right side in left-handed people.

Writing and the Ventral Premotor Cortex

- Subjects viewing letters activated the ventral premotor cortex in the hemisphere used for writing: the left hemisphere in right-handed subjects (yellow) and the right hemisphere in left-handed subjects (red).

Phonological Dysgraphia (语音性书写困难)

- A writing disorder in which the person cannot sound out words and write them phonetically.

- Thus, they cannot write unfamiliar words or pronounceable nonwords, such as the ones presented in section on reading.

- They can, however, visually imagine familiar words and then write them.

Orthographic Dysgraphia (正字法书写困难)

- Orthographic dysgraphia is just the opposite of phonological dysgraphia: It is a disorder of visually based writing.

- A writing disorder in which the person can spell regularly spelled words but not irregularly spelled ones.

- People with orthographic dysgraphia can only sound words out; thus, they can spell regular words such as care or tree, and they can write pronounceable nonsense words.

- However, they have difficulty spelling irregular words such as half or busy (Beauvois and Dérouesné 1981); they may write haff or bizzy.

Direct Dysgraphia (Semantic agraphia ) (直接书写困难)(语义失写症)

- can write words that are dictated to them even though they cannot understand these words.

Reading and Writing Disorder Produced by Brain Damage

| Reading Disorder | Whole-word Reading | Phonetic Reading | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure alexia | Poor | Poor | Can write |

| Surface dyslexia | Poor | Good | No Data |

| Phonological dyslexia | Good | Poor | No Data |

| Direct dyslexia | Good | Good | Cannot comprehend Words |

| Writing Disorder | Whole-word Writing | Phonetic Writing | No Data |

| Phonological dysgraphia | Good | Poor | No Data |

| Orthographic dysgraphia | Poor | Good | No Data |

| Semantic agraphia (direct dysgraphia) | Good | Good | Cannot comprehend words |

Summary

Three perceptual dimensions of sound:

- Pitch

- Loudness

- Timbre

The anatomy of ear:

- Tympanic membrane $\rarr$

- Three ossicles (Malleus, Incus, Stapes) $\rarr$

- Oval window and Round windows $\rarr$

- Cochlea (Basilar membrane, Hair cells, Tectorial membrane)

The auditory pathway:

- Cochlear nerve (axons of hair cells) $\rarr$

- Cochlear nucleus $\rarr$

- Superior olivary complex $\rarr$

- Inferior colliculus $\rarr$

- Medial geniculate nucleus $\rarr$

- primary auditory cortex (Core region) $\rarr$

- Belt region $\rarr$

- Parabelt region

Perception of pitch:

- Place coding (high frequency); rate coding (low frequency )

Perception of timbre:

- Fundamental frequency, overtone

Perception of sound location:

- Binaural cues (intensity, timing, phase), echolocation

Dorsal where stream and ventral what stream

Vestibular system

- Semicircular canals, vestibular sacs, hair cells, vestibular nerve

Aphasia:

| Disorder | Areas of lesion | Spontaneous****Speech | Comprehension | Repetition | Naming |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broca’s aphasia | Frontal cortex rostral to the base of the primary motor cortex (Broca’s area) | Nonfluent | Good | Poor | Poor |

| Wernicke’s aphasia | Posterior portion of superior temporal gyrus (Wernicke’s area) and posterior language area | ||||

| Pure word deafness | Wernicke’s area or its connection with the primary auditory cortex | Fluent | Poor | Poor | Good |

| Transcorticalsensoryaphasia | Posterior language area | Fluent | Poor | Good | Poor |

| Conduction aphasia | White matter beneath parietal lobe superior to lateral fissure (arcuate fasciculus) | Fluent | Good | Poor | Good |

| Anomic aphasia | Various parts of parietal and temporal lobes | Fluent | Good | Good | Poor |

Alexia/ dyslexias and dysgraaphia

| Reading Disorder | Whole-word Reading | Phonetic****Reading | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure alexia | Poor | Poor | Can write |

| Surface dyslexia | Poor | Good | No Data |

| Phonological dyslexia | Good | Poor | No Data |

| Direct dyslexia | Good | Good | Cannot comprehend Words |

| Writing Disorder | Whole-word Writing | Phonetic Writing | Remarks |

| Phonological dysgraphia | Good | Poor | No Data |

| Orthographic dysgraphia | Poor | Good | No Data |

| Semantic agraphia (direct dysgraphia) | Good | Good | Cannot comprehend words |