L17 Membrane Transport

一、Transport Across Membranes

Molecules transport across membrane. the methods can include the actions of small molecules that act as ion carriers, larger proteins that are highly specific transporters, and proteins that promote the formation of membrane vesicles.

Thermodynamics of Transport

The thermodynamics can be shown in the $\Delta G$ form.

Suppose transporting one mole of a substance from a location in which its concentration is $C_{1}$ to a different location where its concentration is $C_{2}$:

$$

\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ ‘} + RT \ln{Q} = -RT \ln{K_{eq}} + RT \ln{\frac{[C_{2}]}{[C_{1}]}}

$$

For a process that only involves transport of some substance across a membrane, the term $\Delta G^{\circ ‘} = 0$

The $\Delta G^{\circ ‘}$ describes the equilibrium state for a process, and for the case of transport across a membrane, the equilibrium state is reached when the concentrations of the substance are the same on both sides of the membrane

此时:

$$

K_{eq} = [C_{2}]/[C_{1}] = 1 \

\because \text{At equilibrium: }\Delta G = 0 \

\therefore \Delta G^{\circ ‘} = -RT \ln{K_{eq}} = 0

$$

For a transport process that is not at equilibrium $[C_{2}] \ne [C_{1}]$, thus $RT \ln{Q} \ne 0$, and $\Delta G$ for the process is given by:

$$

\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ ‘} + RT \ln{Q} = 0 + RT \ln{\frac{[C_{2}]}{[C_{1}]}} = RT \ln{\frac{[C_{2}]}{[C_{1}]}} \text{ (Equation 10.1 (b))}

$$

According to this equation, if is $[C_{2}]$ less than $[C_{1}]$, $\Delta G$ is negative, and the process is thermodynamically favorable.

As more and more substance is transferred (between the two locations), $[C_{1}]$ decreases and $[C_{2}]$ increases, until $[C_{2}] = [C_{1}]$

At this point $\Delta G = 0$ and the system is at equilibrium.

There are three circumstances under which this equilibrium state can be circumvented (设法克服或避免(某事物);回避), and each is important in the behavior of real membranes:

1. Chemically Modified

A substance may be preferentially bound by macromolecules confined to one side of the membrane or it may be chemically modified once it crosses.

We may find that compound A is more concentrated inside a cell (in terms of total moles of A per unit volume) than outside. But much of A may be bound to some cellular macromolecules or may have been modified; that portion does not really count in Equation 10.1

which simply states that the concentrations of free A on the two sides must be equal at equilibrium.

An appropriate example is oxygen in erythrocytes. If we were to measure the total oxygen concentration in an erythrocyte, we would find it higher than the concentration of in the surrounding blood plasma. But the total concentration inside the cell includes oxygen bound to hemoglobin. The free oxygen concentration in the fluids inside and outside an erythrocyte is the same at equilibrium.

2. Membrane Electrical Potential

A membrane electrical potential may be maintained across a membrane that influences the distribution of ions.

This tendency can be expressed quantitatively in the following way. For an ion of charge Z, the free energy change for transport across a cell or organelle membrane now involves two contributions:

- the normal concentration term, as given in Equation 10.1b

- a second term describing the energy change (or work involved) in moving a mole of ions across the potential difference.

We consider a process in which one mole of ions is transported from outside to inside.

$$

\Delta G = RT \ln{\frac{[C_{in}]}{[C_{out}]}} + ZF \Delta \psi \text{ (Equation 10.2)}

$$

Here $F$ is the Faraday constant ($96.5 kJ \ mol^{-1} V^{-1}$); $\Delta \psi$ is the membrane potential in volts. We define $\Delta \psi$ in terms of the initial and final locations of the transported ion $\Delta \psi = \psi_{final} - \psi_{initial}$, in this case, $\Delta \psi = \psi_{in} - \psi_{out}$.

In this example, $\Delta \psi$ will be negative if the inside of the membrane is negatively charged compared to the outside. Under these conditions, if Z is positive, the $ZF\Delta \psi$ term in Equation 10.2 is negative and makes more exergonic (favorable).

equilibrium state $(\Delta G = 0)$ will not correspond to the same concentration of ions on the two sides of the membrane. However, energy must be expended continually to keep up the potential difference; otherwise migration of ions would neutralize it.

Conversely, Equation 10.2 may be interpreted to mean that if a difference in ionic concentration is maintained, an electrical potential will be produced across the membranes

3. Active Transport (Coupled Favorable Reaction)

If some thermodynamically favored process is coupled to the transport, then the $\Delta G^{\circ ‘}$ and RT ln Q for this favorable process must be included in the free energy equation

$$

\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ ‘} + RT \ln{\frac{Q[C_{in}]}{[C_{out}]}}

$$

Where $Q$ includes activities for the species in the favorable reaction that is coupled to the transport of C

If the substance C being transported is an ion we must also include the $ZF\Delta \psi$ term

$$

\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ ‘} + RT \ln{\frac{Q[C_{in}]}{[C_{out}]}} + ZF\Delta \psi

$$

This equation is a generalization of Equation 10.2, now allowing a variety of processes—not just those that maintain an electrical potential difference—to participate in the transport. In the case where hydrolysis of one mol of ATP results in transport of n mol of an ion C, we must modify Equation 10.3b to include the proper stoichiometry:

$$

\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ ‘} + RT \ln{\frac{Q[C_{in}]^{n}}{[C_{out}]^{n}}} + nZF\Delta \psi

$$

Where $n = $ mol of C transported per mol of ATP. We will show examples of such calculations in the discussion that follows.

Nonmediated Transport

For a substance that can pass through a membrane, the normal state of equilibrium is achieved when the concentrations of the substance are equal on both sides of the membrane.

Equalization of the concentrations of some substance across a membrane can be circumvented by:

binding of the substance to macromolecules

maintaining a membrane potential (if the substance is ionic)

coupling transport to an exergonic process

The rate of nonmediated transport (Molecular Diffusion), as measured by membrane permeability, is proportional to the diffusion and partition coefficients and inversely proportional to membrane thickness.

The net rate of transport:

$$

J = -\frac{KD_{l}(C_{2} - C_{1})}{l}

$$

$J$ is in moles per square centimeter per second, which is proportional to the concentration difference $(C_{2} - C_{1})$

$l$ is the thickness of the membrane, $D_{l}$ is the diffusion coefficient

$K$ is the partition coefficient for the diffusing material between membrane lipid and water

net transport will stop when $C_{2} = C_{1}$

We usually do not know $K$ either $D_{l}$ or the exact thickness of the membranes involved, so we often describe the rate of passive transport in terms of a permeability coefficient, P, which can be measured by direct experiment:

$$

J = -P(C_{2} - C_{1})

$$

$$

P = \frac{KD_{l}}{l}

$$

with units of cm/s

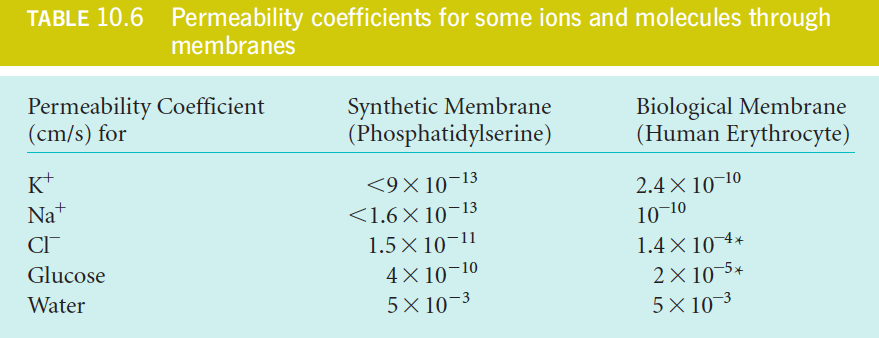

The low P values of the ions are as expected because ions have low values of K

Facilitated Transport

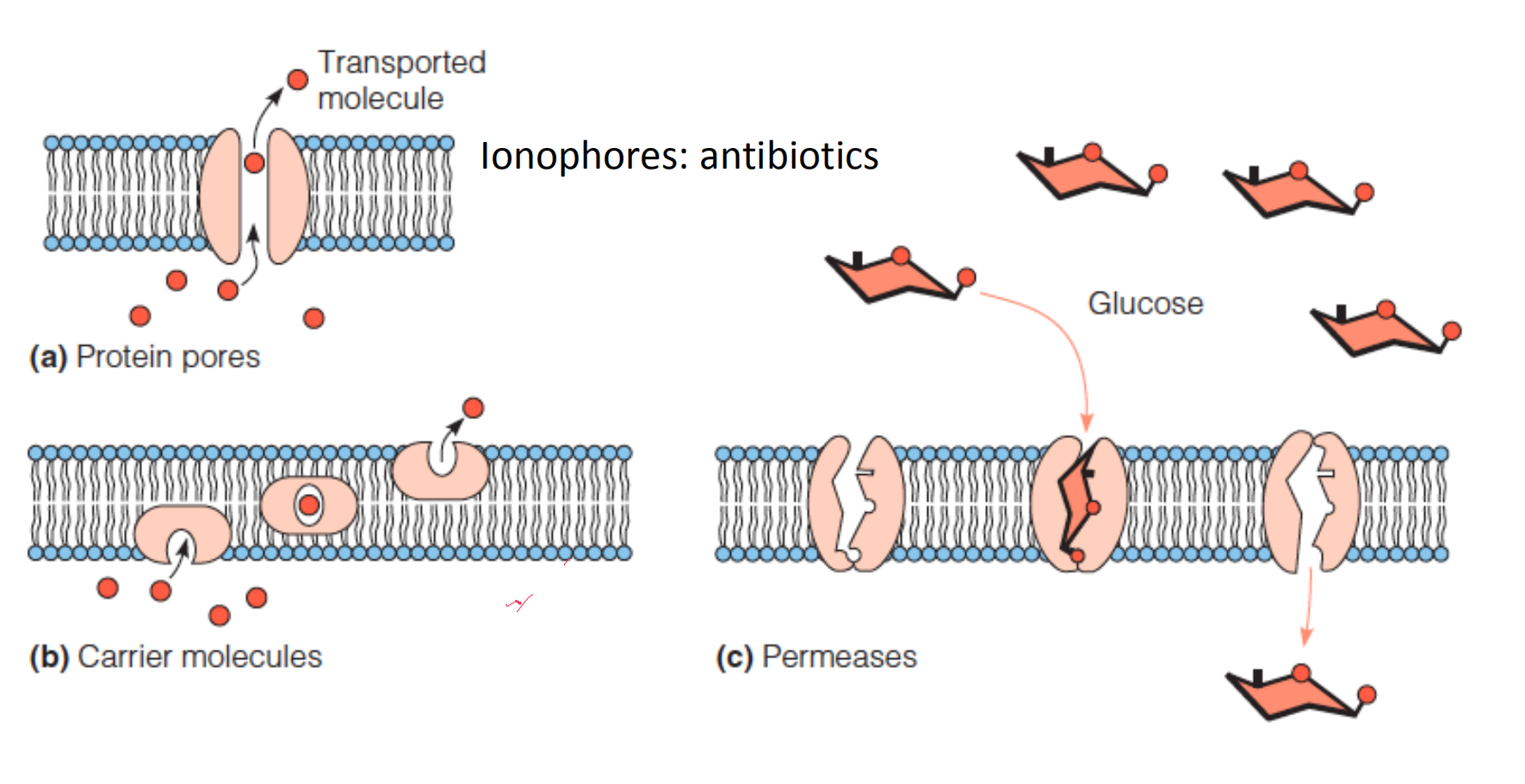

Facilitated transport, via (1)pores, (2)permeases (渗透酶), or (3)carriers, can increase the rate of diffusion across a membrane by many orders of magnitude.

Facilitated transport does not change the thermodynamics

1. Carriers

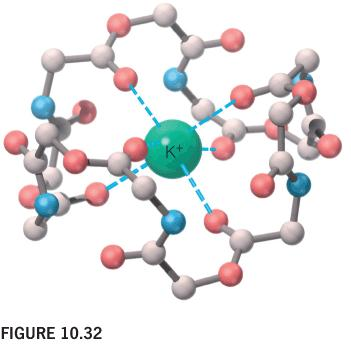

Valinomycin(缬氨霉素) is an antibiotic that acts as an ion carrier.

The outside of this roughly spherical cyclic polypeptide is hydrophobic.

The central cavity surrounded by oxygens complexes a K+ ion.

The surface is covered with CH3 groups (not shown)

2. Pore

hemolysin

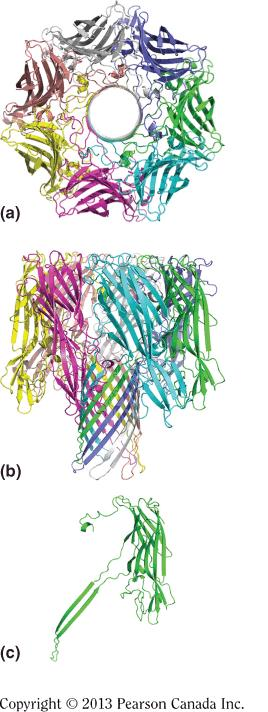

The channel-forming hemolysin(溶血素) from S. aureus:

Ribbon drawings of the a-hemolysin heptamer*,* viewed

looking down the sevenfold axis

perpendicular to the sevenfold axis

one protomer extracted from the heptamer structure

The heptamer is 10 nm in diameter and 10 nm in length, as measured along the sevenfold axis.

The β-barrel stem, which penetrates the membrane, is about 6 nm long.

Specially, the thickness of lipid bilayer is also 6nm.

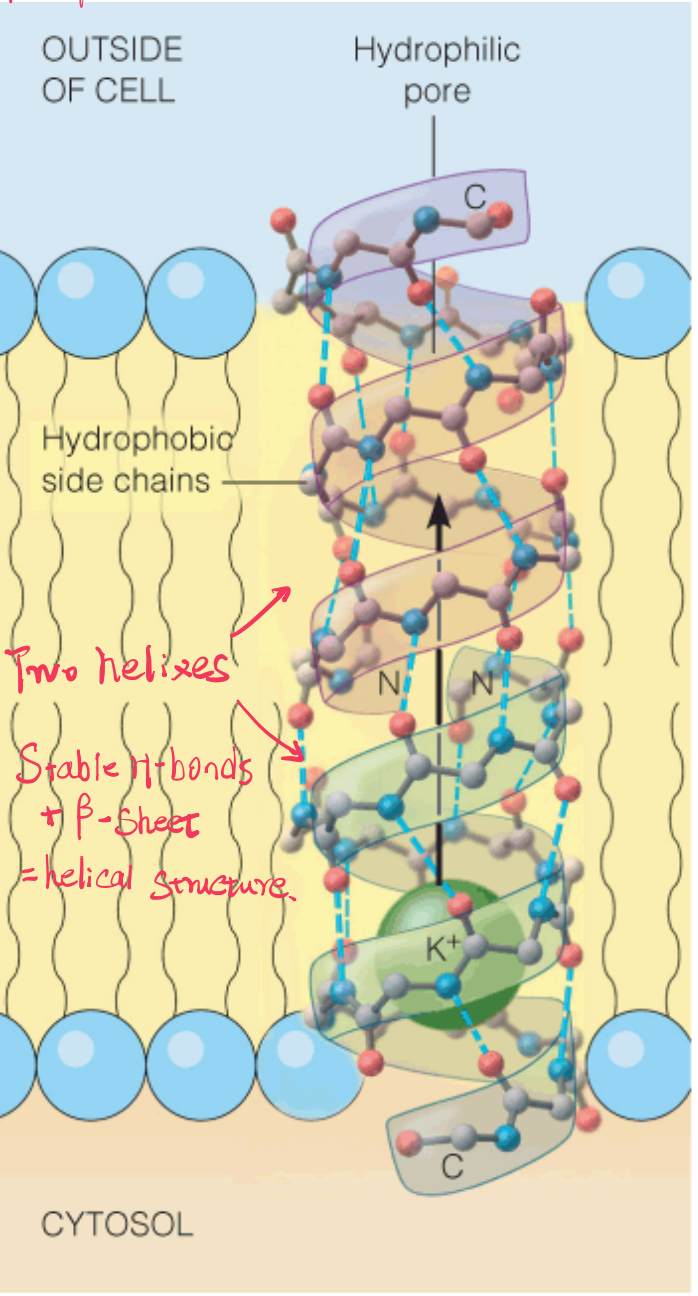

Gramicidin A

Gramicidin A(土霉素A) is an antibiotic that acts as an ion pore.

Two molecules of gramicidin A form a pore through the membrane by adopting a helical conformation, with their hydrophobic side chains in contact with the lipid.

In the hydrophobic environment, the H-bond is strong. Therefore the peptide tends to form a helix.

Note the N-termini are inside and the C-termini are outside the bilayer core.

The inside of the helix forms the hydrophilic pore.

The hydrogen bonding in this open helical structure resembles that in β-sheet polypeptides. This is possible because of the alternating D and L residues

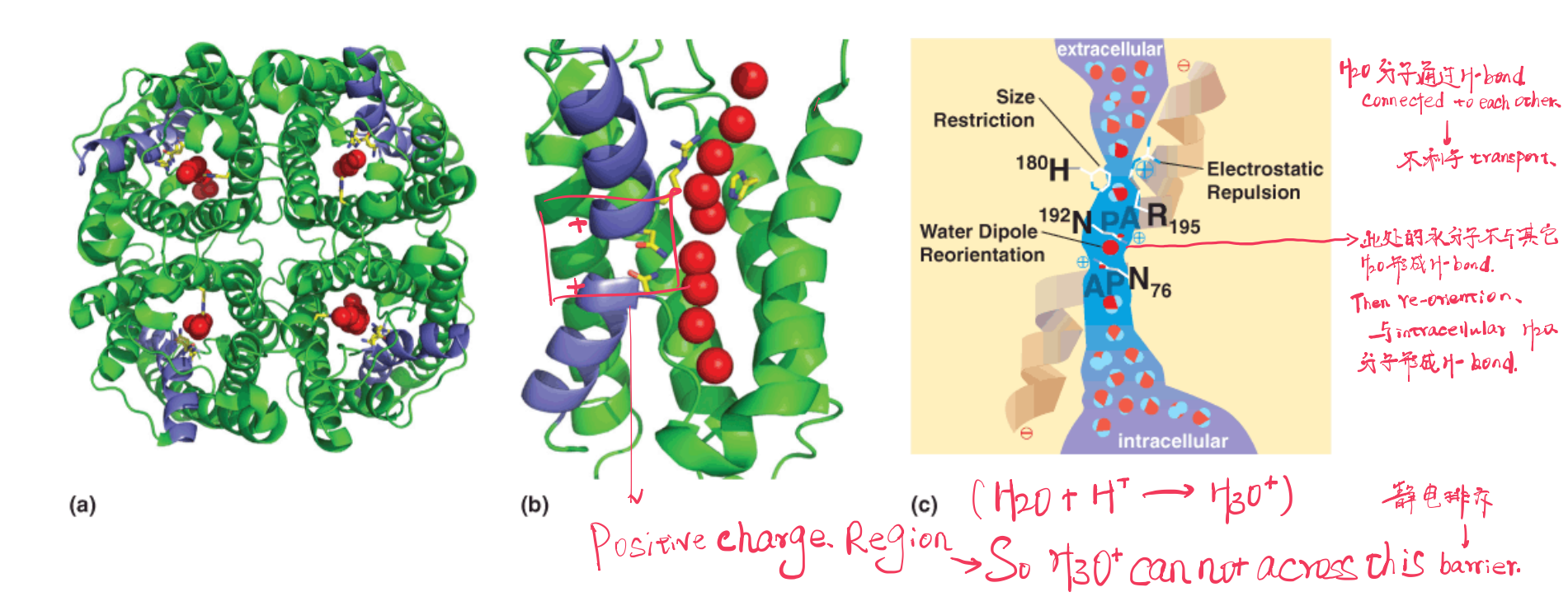

aquaporins (Water Channel)

Many types of eukaryotic cells must move large amounts of water rapidly across their membranes as part of their physiological function.

Erythrocytes (which experience a wide range of solution osmolarity as they transit through lungs, capillaries, and kidneys)

Secretory cells in salivary glands

Epithelial cells in the kidney

Although water can cross membranes, it does so relatively slowly; thus, the inherent permeability of membranes toward water is not sufficient to support the rapid transport observed in many cell types.

Such rapid transport is achieved by water-specific channels called aquaporins (水通道蛋白).

The aquaporins function as tetramers of identical monomers.

Each monomer contains six membrane-spanning helices and two shorter helices that contain a conserved N-terminal Asn-Pro-Ala (NPA) motif.

Crystal structures of the aquaporins reveal that selectivity for water is achieved by three means.

- First, the channel is quite narrow (~0.28 nm) and excludes anything larger than a water molecule (including hydrated ions).

- Second, $H_{3}O^{+}$ is excluded by electrostatic repulsion. A conserved Arg places a (+) charge at this constriction, effectively repelling any cations. In addition, the two shorter helices are oriented with their N-termini pointing into the narrowest part of the channel; thus, the positive ends of the helical macrodipoles provide additional repulsion to Third, water molecules can only pass through the channel in single file.

As they do so, main chain carbonyl groups as well as the conserved Asn72 and Asn192 side chains in the conserved NPA motifs form H-bonds with the individual water molecules, thereby reorienting the water molecules and disrupting H-bonding between the water molecules in the channel.

This is a critical feature of the transport mechanism because it prevents protons from traversing the membrane via an H-bonding network of water molecules

many membranes must maintain ion gradients to carry out critical processes (e.g., bacterial flagellar motion, ATP synthesis, firing of neurons, etc.). The aquaporins elegantly solve the problem of maintaining the osmotic balance in a cell while not destroying critical ion gradients.

H

2O分子会与H+离子结合形成H3O+以水通道蛋白为例,整个大分子由多个helix组成,两条helix的N-terminal组合形成Positive Charge Region,这个区域具有筛选分子的作用。

在水通道的两端都存在大量的水分子,它们互相形成氢键,而相互间氢键的形成并不利于水分子的运输。在Positive Charge Region中的水分子不会与其他水分子形成氢键,同时由于正电性对H

3O+具有的排斥作用,使得当前的水分子可以re-orientation,接着与水通道蛋白另外一侧的大量水分子形成氢键,从而实现“通道”的运输作用。

3. Permeases

Membrane-spanning proteins that recognize specific molecules for transport are called permeases or transporters.

One example is The glucose transporter in erythrocytes (GLUT1, or band 4.5 protein) is thought to operate in this way

namely, the permease shifts between two conformations: one open only to the “out-side,” and the other open only to the “inside.” Thus, the permease never forms a pore that allows unrestricted flow of the transported substrate

When transport of the two molecules, or ions, is in the same direction, the transporter is referred to as a symport; when the substrates move in opposite directions, the transporter is called an antiport.

This cotransport strategy allows the thermodynamically unfavorable transport of some substrate against its concentration gradient, when coupled to the favorable transport of the cosubstrate.

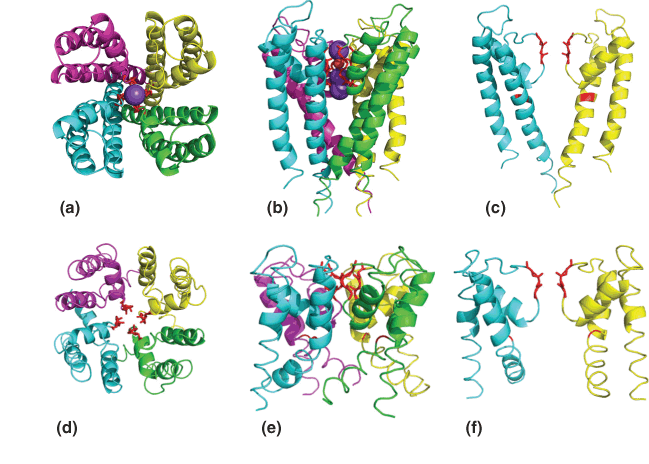

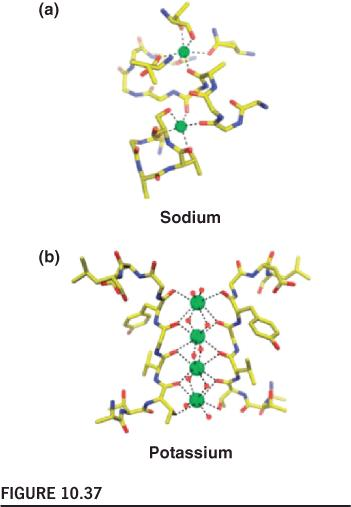

4. Ion Selectivity And Gating

Ion selectivity is achieved by optimal geometry of chelating groups (螯合基团) in ion channels

The structure of the potassium channel pore:

每一个单体都组成”Filter”的一部分

It is critical that the activity of any ion channel is regulated to maintain proper cell function; thus, there should be “open” (i.e., ion-conducting) and “closed” conformations for the channel. The switching between conductive and nonconductive conformations is called gating.

Selective Binding

Selective binding of Na+ and K+ in ion channels:

Two binding sites make up the selectivity filter in the transmembrane region of LeuT.

Four are bound in the filter of the KcsA channel

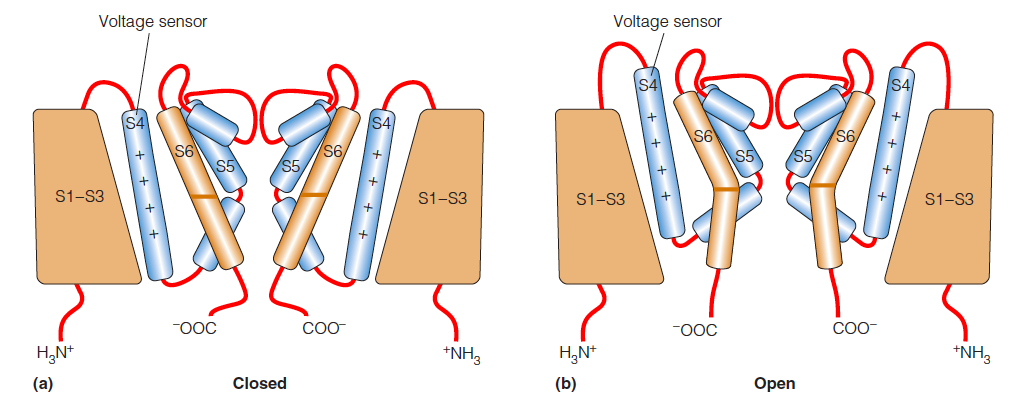

voltage-gating

A model for voltage-gating in the channel:

The channel portion of the voltage-gated channel is structurally homologous to the KcsA channel.

The Arg- and Lys-rich S4 helices are highlighted in blue.

The depth of these helices in the bilayer changes as a function of the membrane potential.

The position of the S4 helix in the channel is thought to change as a function of the membrane potential ($\Delta \psi$)

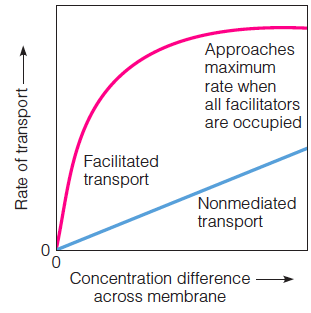

Distinguishing Facilitated from Nonmediated Transport

The rate of facilitated diffusion approaches a maximum value when all available transporters are saturated with substrate, whereas nonmediated diffusion shows a linear increase in rate as substrate concentration increases.

a simple test is that facilitated transport systems are saturable. Any membrane has a limited number of tranporters.

Each carrier or permease can handle only one molecule or ion at a time; each pore can accommodate only one or a few ions or molecules at any moment

The rate of nonmediated transport, on the other hand, increases linearly with the concentration difference, as predicted by Equation 10.4 or 10.5, because there are no sites to saturate.

There is also an easy way to distinguish between pore-facilitated and carrier-facilitated diffusion. The latter should be extremely sensitive to membrane fluidity because the carrier must actually move in the membrane. If the temperature of a membrane is lowered below its fluid–gel transition temperature, transport by a carrier like valinomycin virtually ceases. Transport by a pore structure like gramicidin A, on the other hand, is affected little by temperature changes.

Active Transport

In active transport, substances are moved across a membrane against a concentration gradient.

Direct or indirect coupling of transport to ATP hydrolysis provides the required free energy.

The Na+-K+ pump acts in all cells to maintain higher concentrations of K+ inside and Na+ outside.

| Ion | Outside | Inside |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 145 mM | 12mM |

| K+ | 4mM | 155mM |

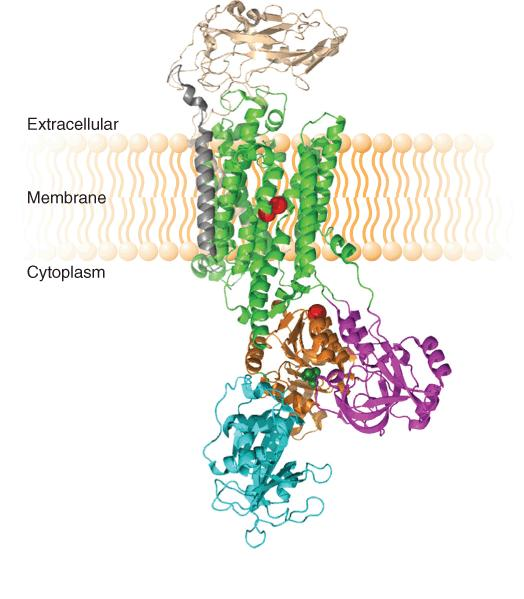

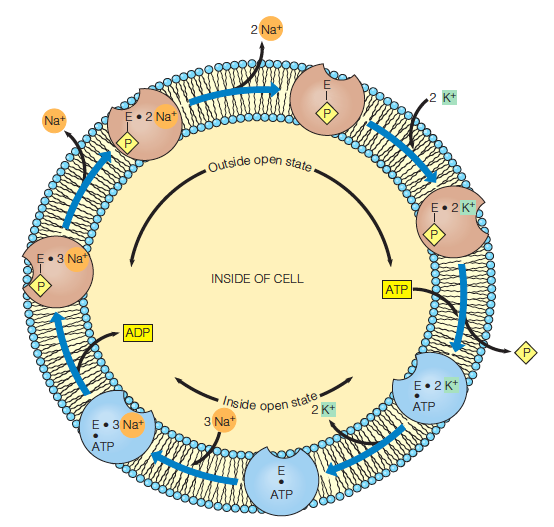

1. Na+-K+ Pump

The structure of the Na+-K+-ATPase with K+ bound:

A schematic diagram of the functional cycle of the Na+–K+ pump:

The subunit is believed to have two states:

one open only to the outside (brown

one open only to the inside (blue)

A dot between two symbols indicates noncovalent binding, a line indicates covalent attachment and (as in phosphorylation).

Cardiotonic steroids (e.g., digoxin) inhibit the Na+–K+ pump,eventually resulting in increased Ca2+ ion concentration in heart muscle, which, in turn, leads to stronger contractions of the heart muscle.

Two $K^{+}$ ions are pumped into the cell and three $Na^{+}$ ions are pumped out for every ATP hydrolyzed.

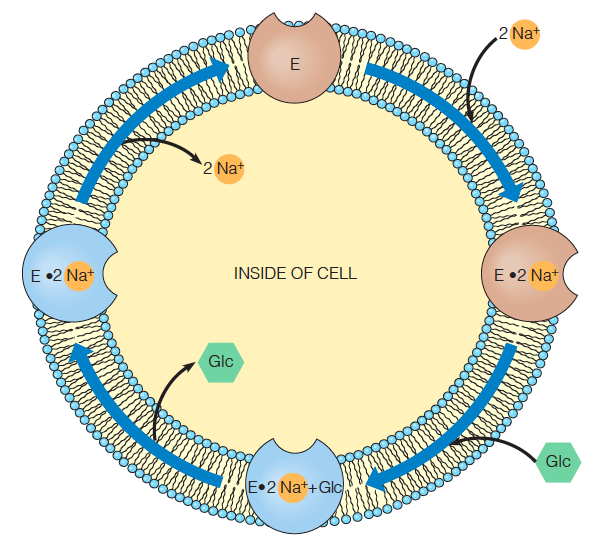

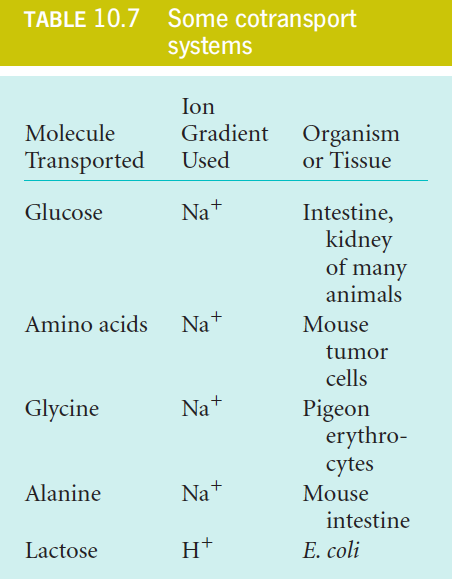

2. Cotransport Systems

In cotransport, the unfavorable movement of a substance through the membrane is coupled to the favorable transport of another substance.

The sodium–glucose cotransport channel is also presumed to have two possible states

one open only to the outside

one open only to the inside of the cell

Transition to the inside open state is stimulated by glucose binding to E$\cdot$Na+

Return to the outside-open state occurs upon Na+ release to the inside of the cell.

The sodium gradient from inside to outside provides the driving force for the unfavorable transport of glucose.

3. Transport By Modification

In transport by modification, a substance that has diffused through a membrane is modified so that it cannot return.

This method is used by many bacteria for the uptake of sugars.

The sugars are phosphorylated, either during their diffusion through the membrane or as soon as they emerge into the cytosol.

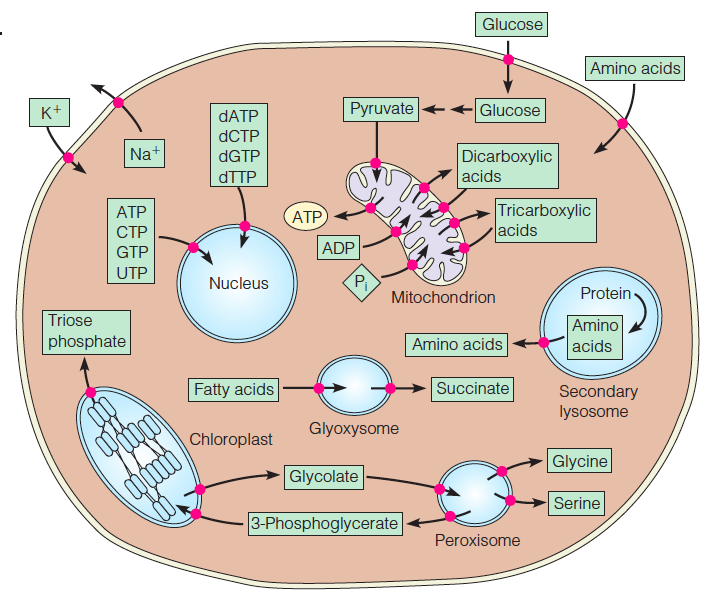

4. Specific transport processes

•This composite plant–animal cell illustrates some of the most important specific transport processes.

•All of the substances shown here, and many more, are transported in specific directions across cellular membranes.

5. Bulk Transport

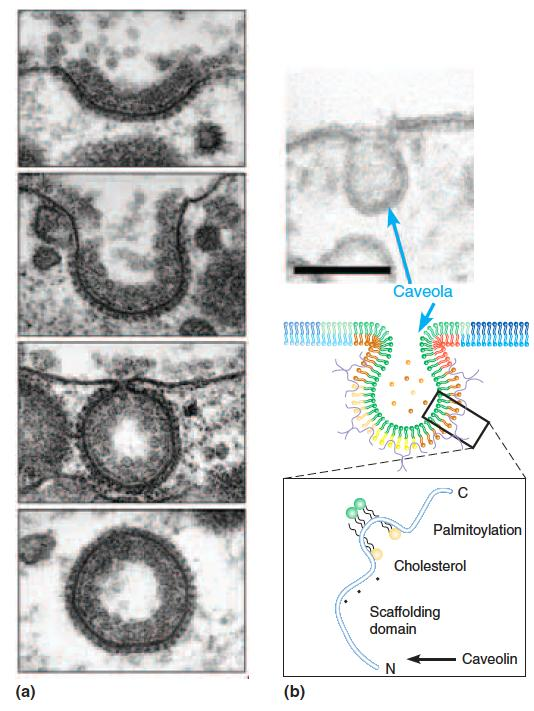

Caveolae and Coated Vesicles 小窝和包膜囊泡

Bulk transport across membranes involves the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles (网格蛋白包被的囊泡) and/or caveolae ((复)小窝,小凹).

Formation of a clathrin-coated vesicle initiates with formation of a coated pit (top two panels), which then buds (third panel from top) forming a free coated vesicle (bottom panel).

Caveola formation occurs at sites rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids due to insertion of caveolin into one leaflet of the membrane. Budding of the caveola yields a free vesicle

二、Excitable Membranes, Action Potentials, and Neurotransmission

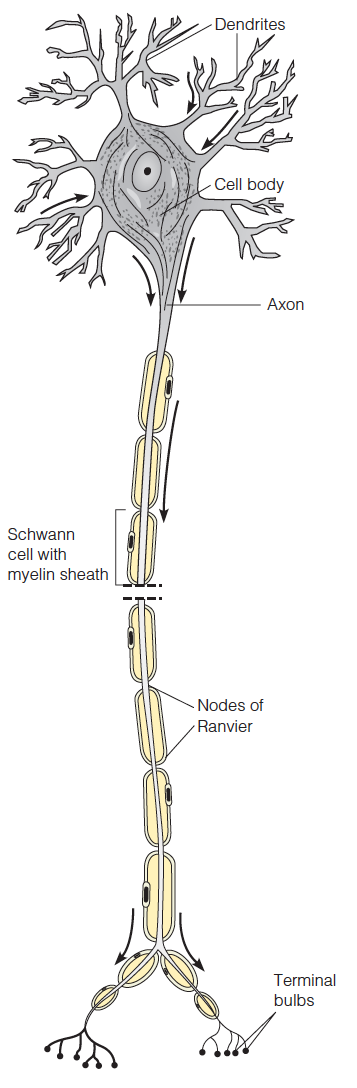

Neurons conduct electrical impulses by membrane potential changes in regions of the plasma membrane cell.

The cell body contains the nucleus and most of the cellular machinery.

The dendrites receive signals from the axons of other neurons

The axon transmits signals via the synaptic termini, which communicate to the dendrites of other neurons or to muscle cells.

Along the axon are Schwann cells, which envelop the axon in layers of an insulating myelin membrane. The Schwann cells are separated by nonmyelinated regions called the nodes of Ranvier

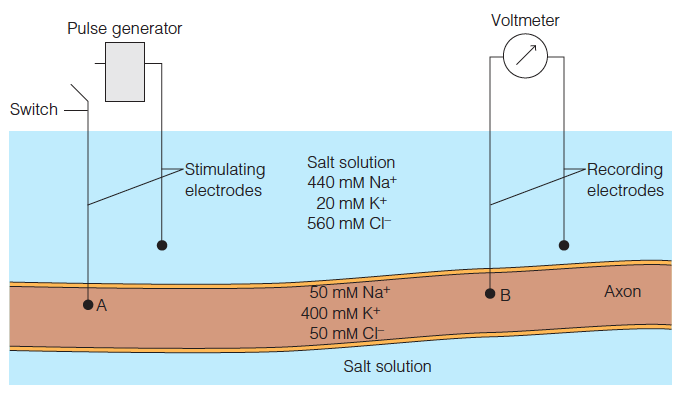

Use of squid giant axons for studies of neural transmission

Electrodes attached to a voltmeter record the potential across the axonal membrane.

At the resting axon ion concentrations shown here, the voltmeter would read about 60 mV.

If the axon is stimulated at point A by a depolarizing pulse, the traveling membrane potential will shortly pass point B, where it can be recorded.

The resting potential of a nerve fiber is determined by the permeabilities of the membrane to different ions, particularly K+ , which has a high permeability due to K+ leak channels.

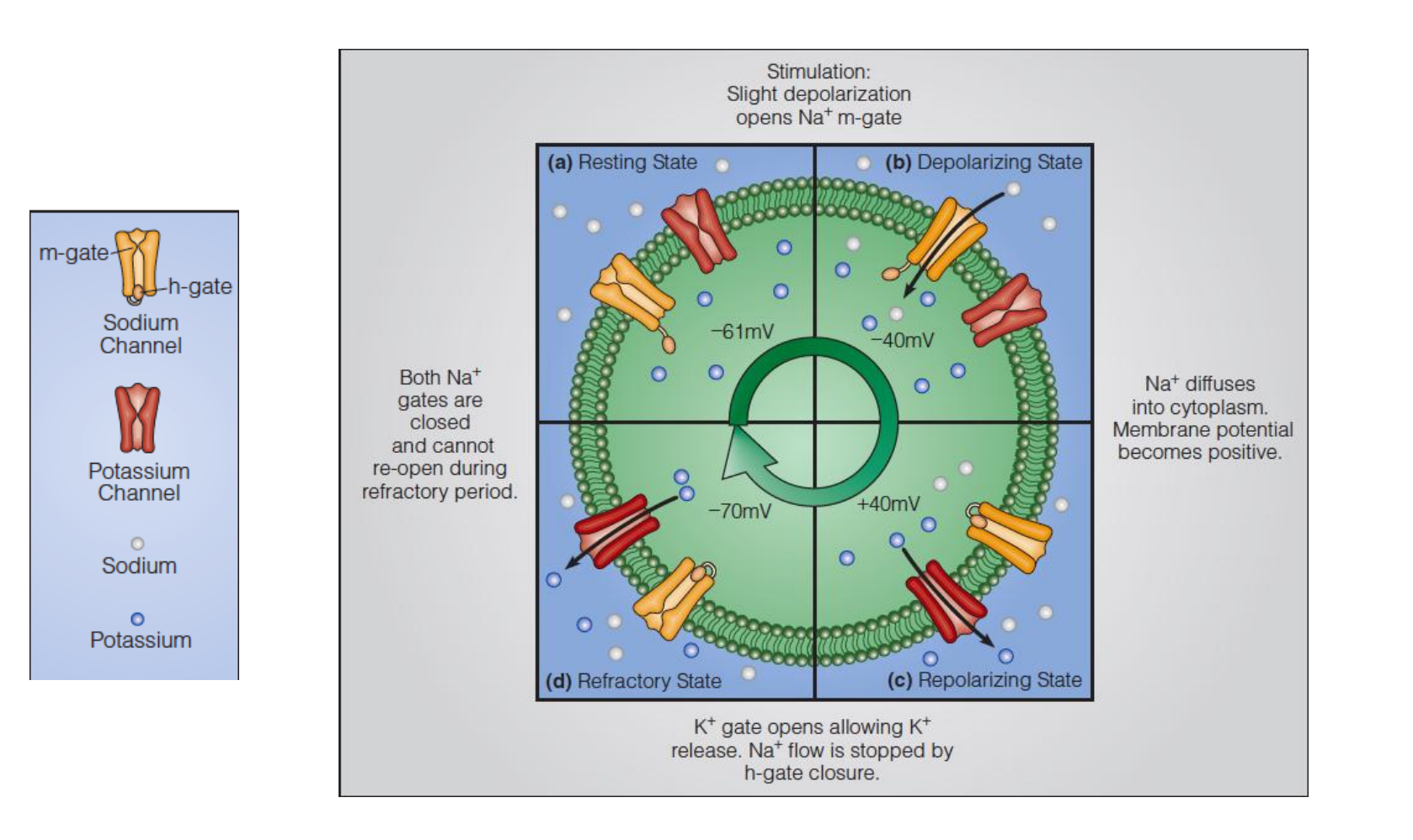

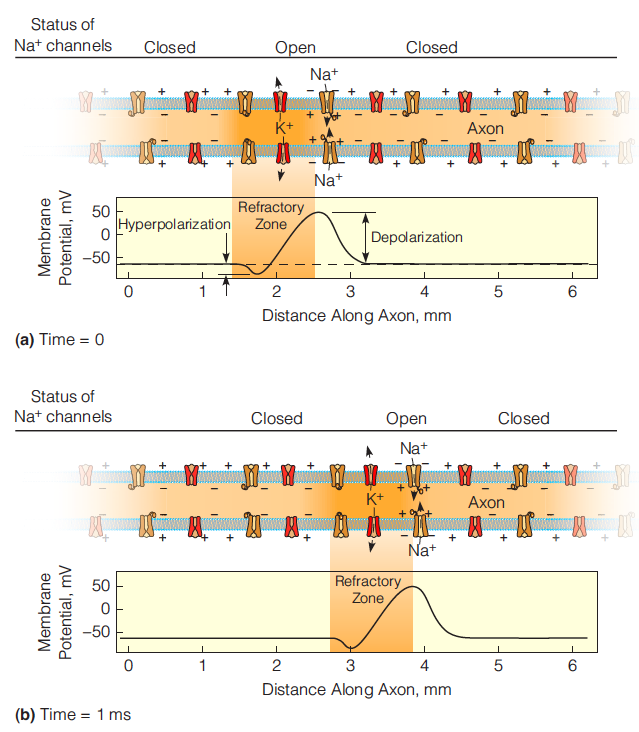

The action potential is generated and propagated because a small depolarization of the nerve cell membrane opens voltage gated channels, allowing ions to flow through.

The voltage-gated channel cycles during an action potential

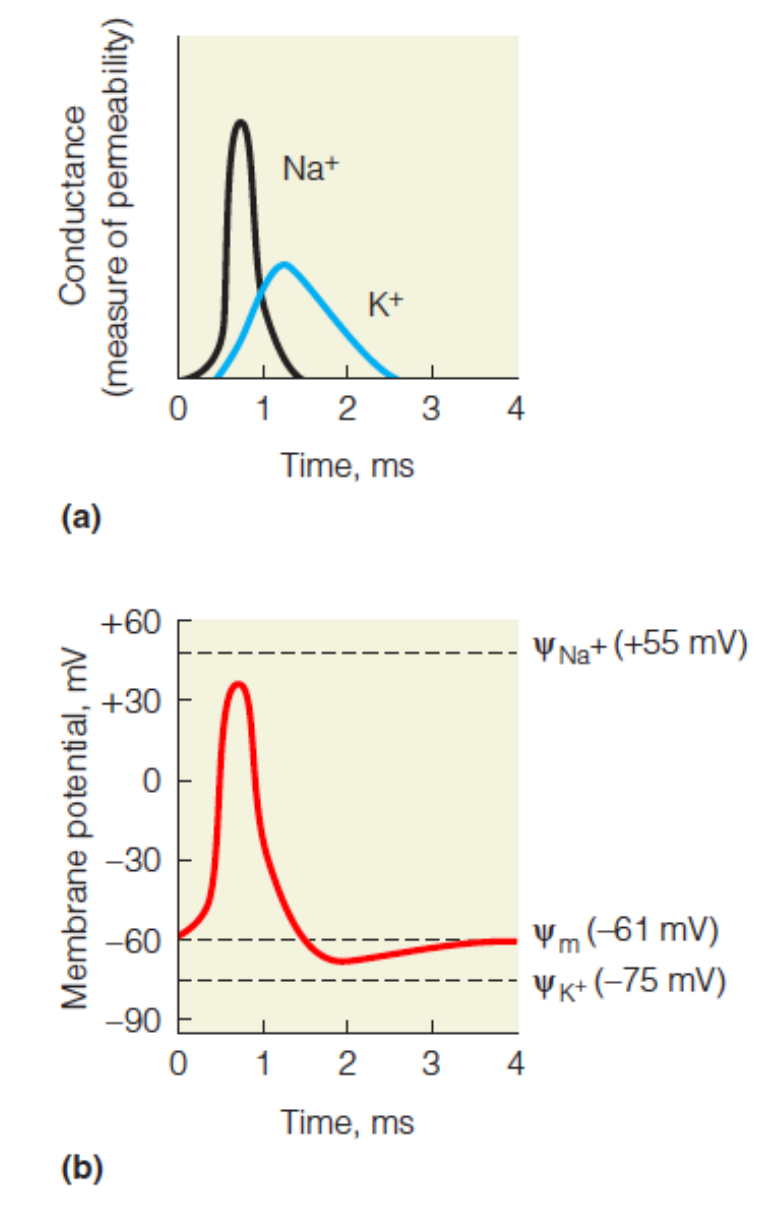

The action potential

Changes in membrane conductance at a point on an axon as a neural impulse passes.

The membrane first becomes permeable to sodium ions, allowing a large inward rush of Na+ . A decrease in the Na+ permeability results and is in turn followed by an outward flow of K+

Changes in membrane potential accompanying the permeability changes shown in Figure(a).

As Na+ rushes in, the potential increases and becomes positive. As K+influx increases, the potential decreases, undershooting the resting potential, before returning to the resting potential.

Transmission of the action potential

1. Toxins

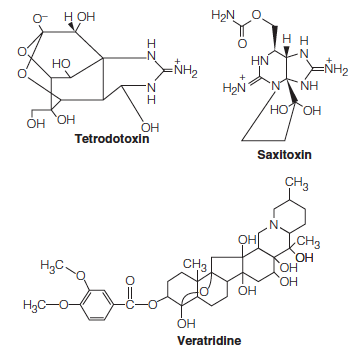

Neurotoxins 神经毒素can act by blocking gates in the axonal membrane in closed or open states.

Tetrodotoxin 河豚毒素is found in some organs of the puffer fish. TTX binds specifically to the Na+ channel, blocking all ion movement.

Saxitoxin 贝类毒素is contained in the marine dinoflagellates responsible for “red tide” also block Na+ channels.

Veratridine is found in the seeds of a plant of the lily family, Schoenocaulon officinale. This toxin also binds to the Na+ channels but blocks them in the “open” configuration.

These toxins have proven to be useful in studies of axonal structure and conduction, for their tight binding makes them excellent affinity labels for the channel

三、Techniques for the Study of Membranes

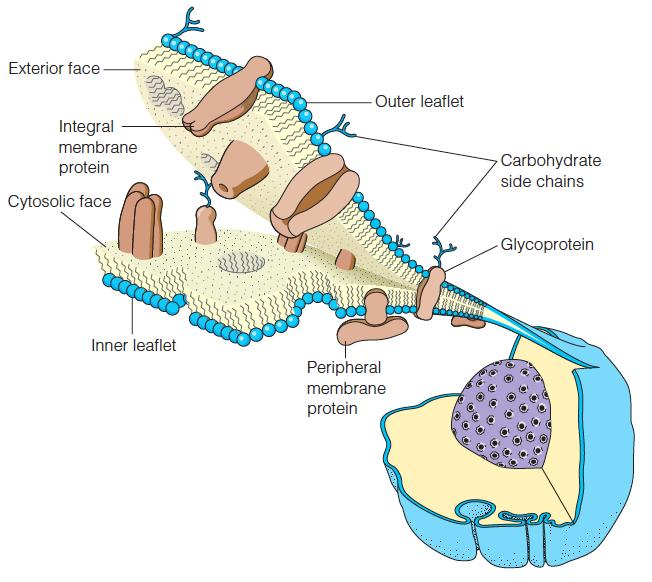

Examination of membrane structure as it exists within cells depends heavily on electron microscopy (EM).

An especially useful variant of this method is the freeze fracture technique.

If a membrane is frozen quickly and then broken by a sharp blow from a microtome knife, it frequently splits along the plane between the bilayer leaflets

Membranes from individual types of cells or purified organelles can usually be obtained by lysis of the cell or organelle, followed by differential centrifugation.

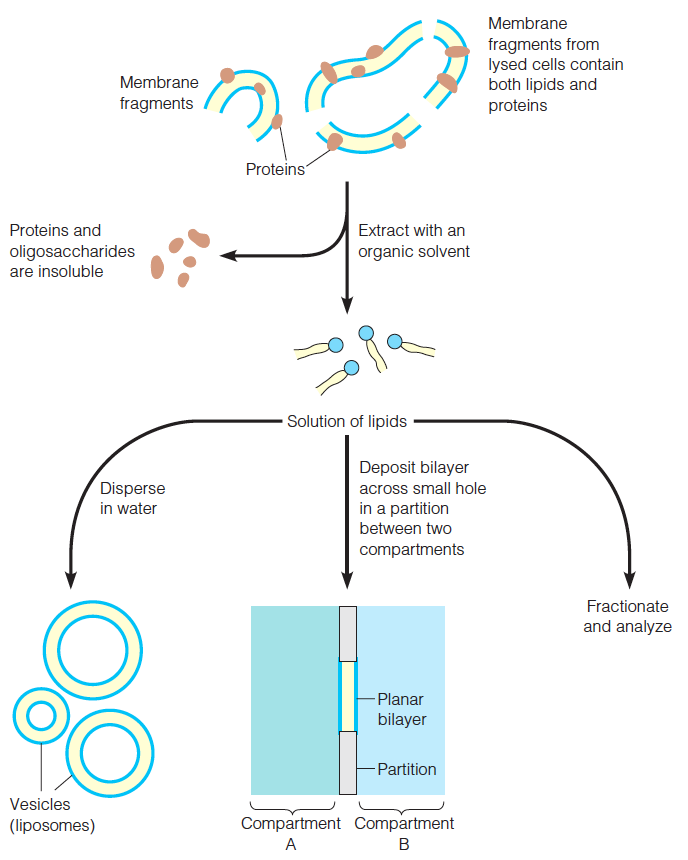

Preparation of vesicles and bilayers

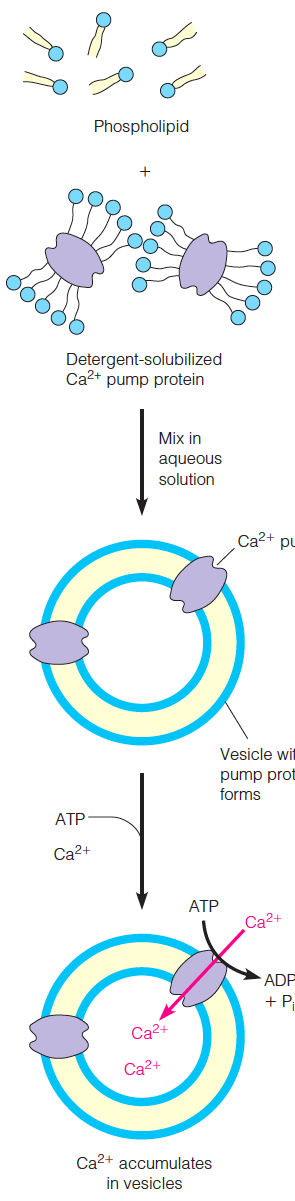

Reconstitution of the Ca2+ pump

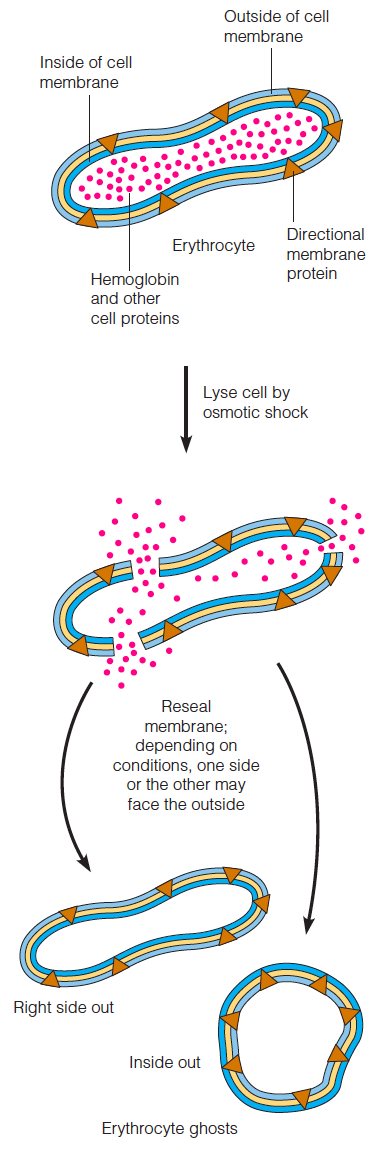

Preparation and resealing of erythrocyte ghosts

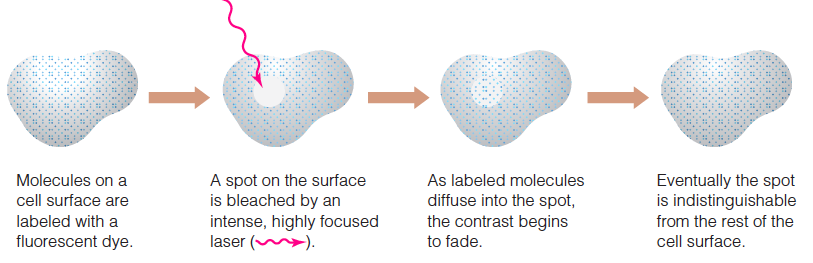

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)