L7 Small molecule transport across the membrane

一、Principles of membrane transport

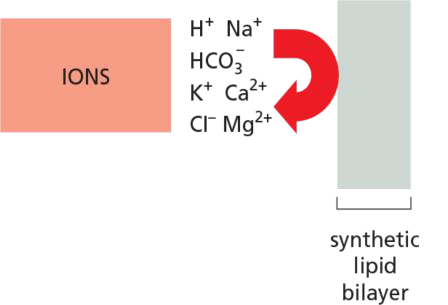

Protein-free lipid are impermeable to ions.

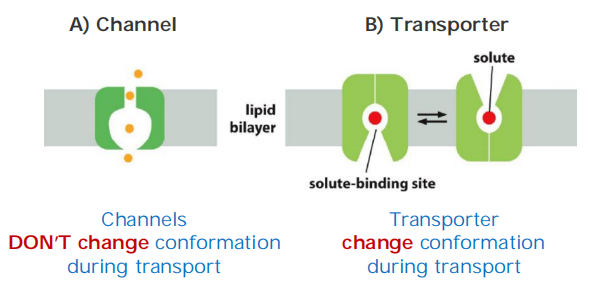

Two main classes of membrane transport proteins: channels and transporters.

Active transport is mediated by transporters couple to an energy source

Diffusion

Diffusion is NOT transport (in strict sense)!

Movement only “down the concentration gradient” (It is not possible to concentrate molecules!!!)

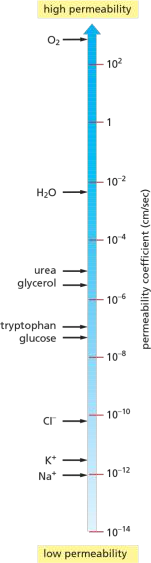

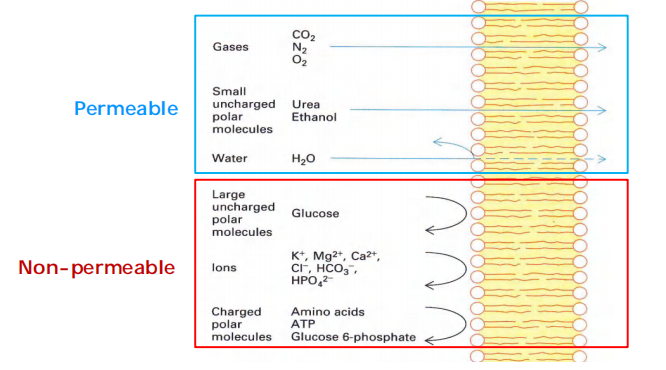

Easy: small non-polar (gases) and uncharged polar, e.g. O2, CO2, N2, urea, EtOH(乙醇)

Impossible: uncharged polar molecules BIGGER than methanol/EtOH; ALL ions

Diffusion is passive (Does NOT consume energy) and not facilitated by other membrane proteins

Relatively slow process

Diffusion rate depends on: concentration, hydrophobicity & size

1. Rates of diffusion

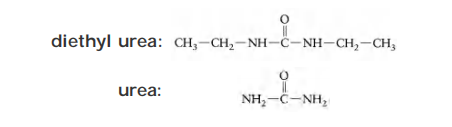

Question: Which can diffuse across the membrane bilayer more rapidly, diethyl urea or urea?

Partition coefficient (K): the ratio of concentration of a substance between oil and water

- diethyl urea: K=0.01

- urea: K =0.0002

The higher a substance’s partition coefficient, the more lipid-soluble it is.

- Diethylurea, which is 50 times (0.01 ÷ 0.0002) more hydrophobic than urea.

- Which of the two substances is more dangerous to handle in the laboratory?

The rate of diffusion, however, varies enormously, depending partly on the size of the molecule but mostly on its relative hydrophobicity (solubility in oil).

In general, the smaller the molecule and the more hydrophobic, or nonpolar, it is, the more easily it will diffuse across a lipid bilayer.

- Small nonpolar molecules, such as O2 and CO2, readily dissolve in lipid bilayers and therefore diffuse rapidly across them. Small uncharged polar molecules, such as water or urea, also diffuse across a bilayer, albeit much more slowly.

By contrast, lipid bilayers are essentially impermeable to charged molecules (ions), no matter how small: the charge and high degree of hydration of such molecules prevents them from entering the hydrocarbon phase of the bilayer

- ions, sugars, amino acids, nucleotides, water, and many cell metabolites that cross synthetic lipid bilayers only very slowly. Special membrane transport proteins transfer such solutes across cell membranes.

Selectively Permeability and Permeability Coefficient

Permeability differs greatly for different substances!

The Permeability coefficient(渗透系数):

ions are blocked because of the charge

2. Factors Influence Diffusion

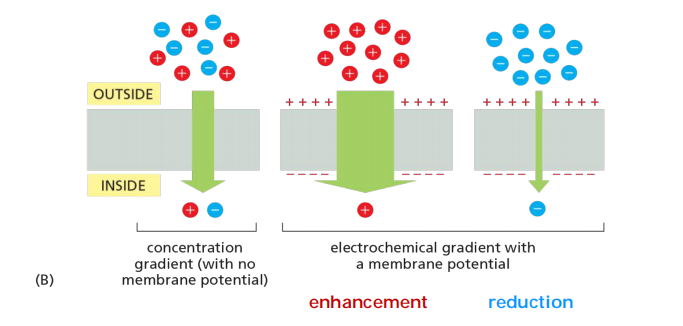

electrochemical gradient

Chemical + charging gradients = electrochemical gradient

- If the concentration (Chemical) gradient is opposite the electro-gradient, then the rate of diffusion is reduced

3. Molecules That Cannot Diffuse Across Lipid Bilayer

Ions

Ions CANNOT pass the lipid bilayer!

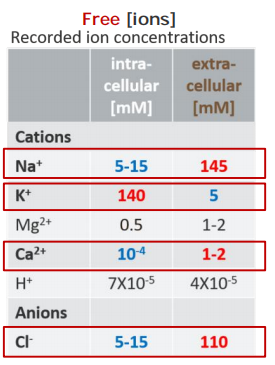

There is a total of about 20 mM Mg2+ and 1-2 mM Ca2+ in cells, but both are mostly bound to proteins and other substances and, for Ca2+, stored within various organelles.

- Free [Ion] $\neq$ Total [Ion]

Inside the cells, higher [K+]free, but lower [Na+]free, [Cl-]free, and [Ca2+]freecompared to those outside of a cell!

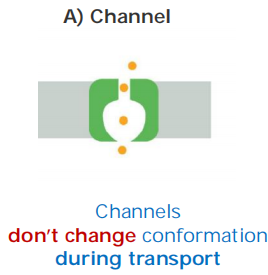

proteins facilitate transport: channels and transporters

- Channels are water-filled pores!

- Channels discriminate on the basis of charge and size: “trapdoors” (活盖,指可以控制开关)

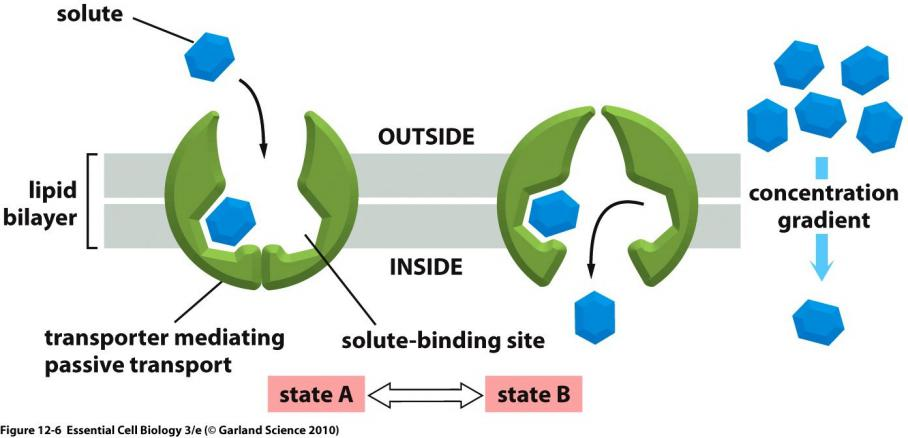

- Transporters alternate between conformations 通过改变构象实现运输

- Transporters discriminate by binding: “keyholes”(锁眼)

Transporters (also called carriers, or permeases) bind the specific solute to be transported and undergo a series of conformational changes that alternately expose solute-binding sites on one side of the membrane and then on the other to transfer the solute across it.

Channels, by contrast, interact with the solute to be transported much more weakly. They form continuous pores that extend across the lipid bilayer. When open, these pores allow specific solutes (such as inorganic ions of appropriate size and charge and in some cases small molecules, including water, glycerol, and ammonia) to pass through them and thereby cross the membrane.

- Not surprisingly, transport through channels occurs at a much faster rate than transport mediated by transporters. Although water can slowly diffuse across synthetic lipid bilayers, cells use dedicated channel proteins (called water channels, or aquaporins) that greatly increase the permeability of their membranes to water, as we discuss later.

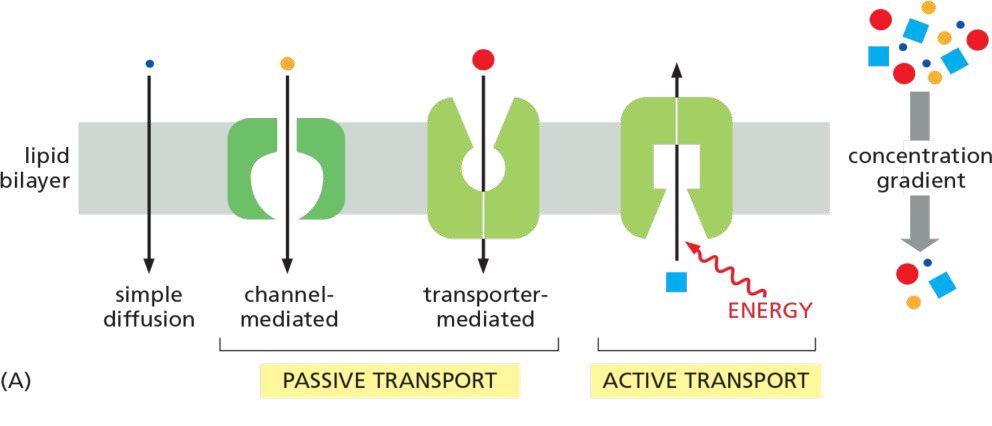

Active vs. Passive transport

Active: energy spent, against concentration gradient—pumps

Passive (facilitated diffusion): energy does not spent, along the concentration gradient

channel 只能是被动运输,transporters可以进行主动运输

All channels and many transporters allow solutes to cross the membrane only passively (“downhill”), a process called passive transport

concentration gradient—drives passive transport and determines its direction

both its concentration gradient and the electrical potential difference across the membrane, the membrane potential

The concentration gradient and the electrical gradient combine to form a net driving force, the electrochemical gradient

In terms of energy consumption,

Passive transport (channels and transporters):

- solutes cross the membrane “down” the electrochemical gradient

Active transport (transporters only)

- solutes cross the membrane against the electrochemical gradient

- needs always some sort of energy

Active transport is mediated by transporters whose pumping activity is directional because it is tightly coupled to a source of metabolic energy, such as an ion gradient or ATP hydrolysis,

Both active and passive ion transport is influenced by the ion’s concentration gradient and the membrane potential—that is, its electrochemical gradient.

二、Transporters

Definition

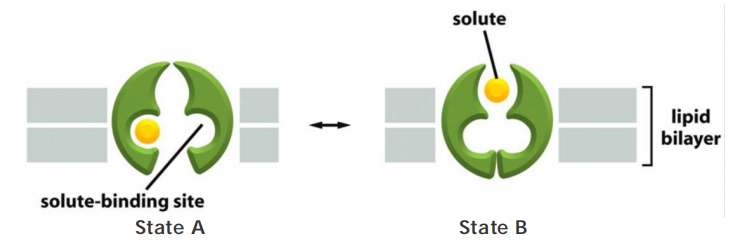

Transporters: great helpers undergoing conformational changes

Features

- Undergo conformational changes

- Bind molecules more tightly

- Transport molecules at a rate of “only” 100-10,000 molecules per second (much lower transport rate than channels)

From Structure to Function

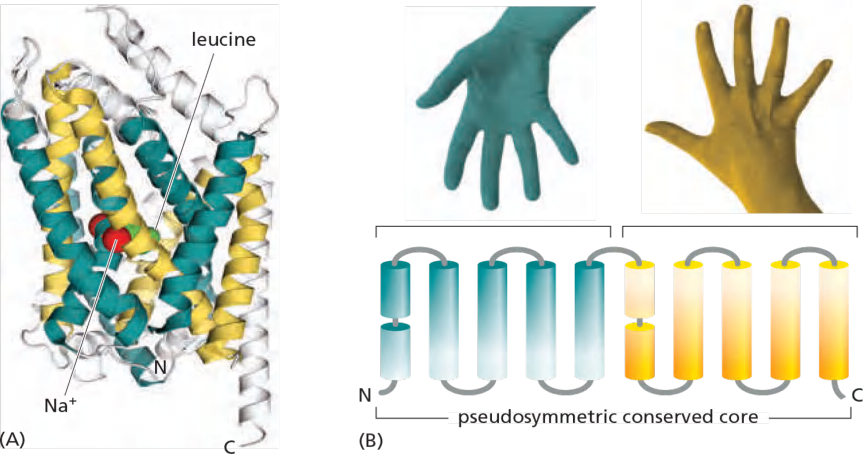

Transporters are typically built from bundles of 10 or more α helices that span the membrane

Because only transporters with both types of binding sites appropriately filled change their conformation, tight coupling between ion and solute transport is assured.

1. Features

Like enzymes, transporters can work in the reverse direction if ion and solute gradients are appropriately adjusted experimentally. This chemical symmetry is mirrored in their physical structure

- Transporters are built from 10 or more $\alpha $-helices.

- The solute binding sites are located midway through the membrane.

- Transporters can work in the reverse direction

- Transporters are built from inverted repeats (structural pseudosymmetry).

Transporters are therefore said to be pseudosymmetric, and the passageways that open and close on either side of the membrane have closely similar geometries

LeuT (a bacterial leucine/Na+ symporter) related to humpan neurotransmitter transporters (e.g. serotonin transporter)

- Both core helix bundles are packed in a similar arrangement

- The second bundle is inverted with respect to the first.

- Structural pseudosymmetry reflects the functional symmetry.

Neurotransmitters (released by nerve cells to signal at synapses—as we discuss later) are taken up again by Na+ symporters after their release.

Categories

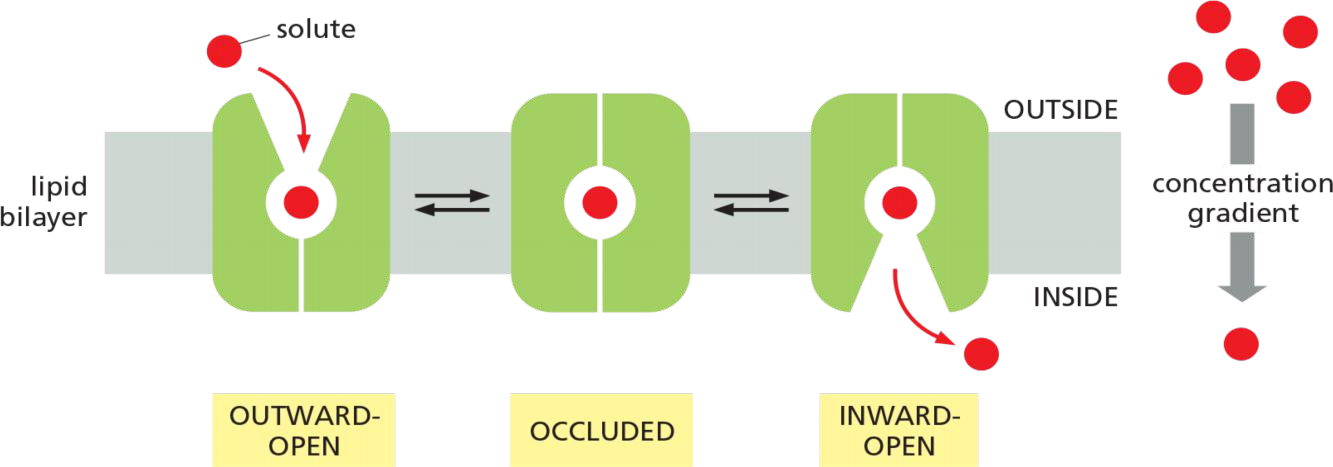

Each type of transporter has one or more specific binding sites for its solute (substrate). It transfers the solute across the lipid bilayer by undergoing reversible conformational changes that alternately expose the solute-binding site first on one side of the membrane and then on the other—but never on both sides at the same time

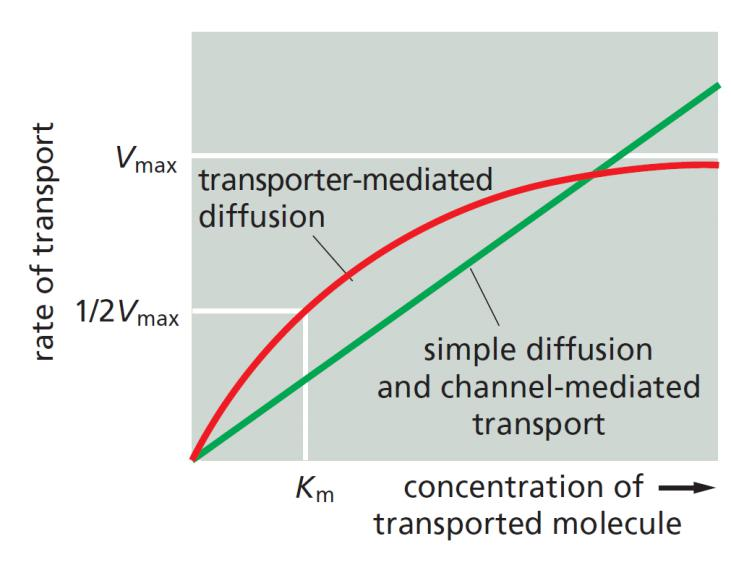

$V_{max}$ measures the rate at which the carrier can flip between its conformational states. In addition, each transporter has a characteristic affinity for its solute, reflected in the Km of the reaction

1. Passive

Conformational changes in transporters mediates the passive movement

Binding and transporting-mediated diffusion resembles enzyme kinetics

Diffusion is proportional to the solute concentration.

Transporter-mediated diffusion resembles enzyme-substrate reaction.

Each type of transporter has one or more specific binding sites for its solute

- the solute-binding sites are saturable, that means the passive transporter also has its own $V_{max}$

- the rate of transport is maximal when the bind-sites are saturated (Vmax)

Each transporter has a characteristic affinity for its solute, reflected in the Km of the binding reaction, which is equal to the concentration of solute when the transport rate is half Vmax.

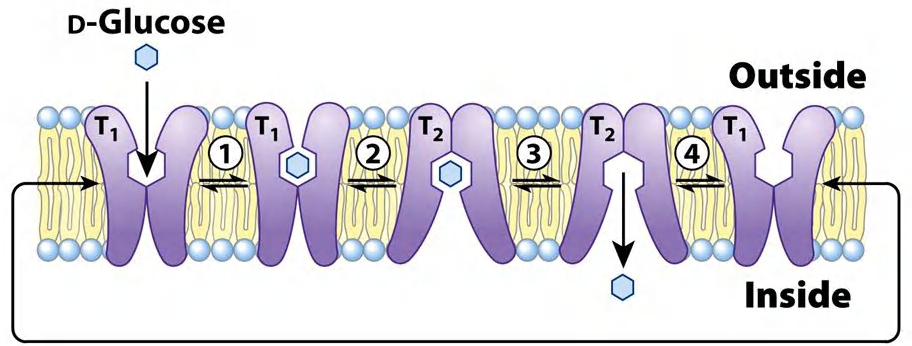

2. Uniporter

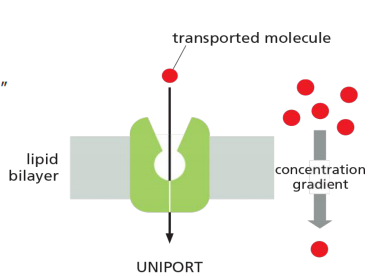

Uniport: transport a single type of molecule “down” its gradient.

Example: GLUT1

E. g. glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1).

- Glucose transporter 1: binds glucose and transfer it along the concentration gradient

- But only D-glucose

- Fueled by a Na+ gradient

- Chemical + charging gradients = electrochemical gradient

GLUT1 transports glucose from the extracellular space into the cytosol (e.g. transports glucose across the blood-brain barrier).

Transport requires conformational change:

- binding pocket is exposed outside and glucose binds

- binding triggers conformational change (transport)

- release triggers conformational change, too

- expose the binding pocket on the outside again

- phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate prevents transport backwards

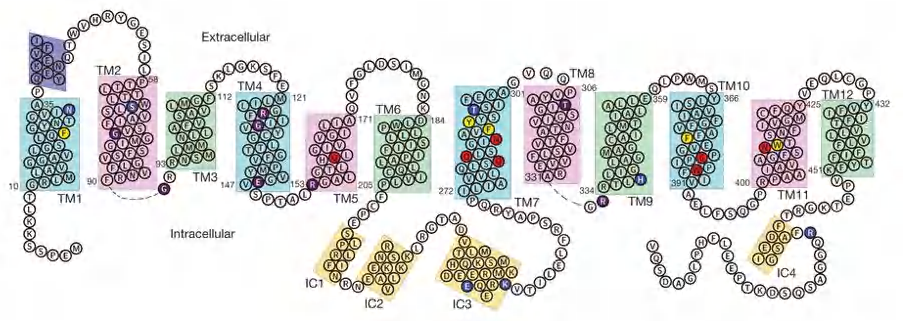

(1) Glucose transporter GLUT1

The human genome encodes 14 homologs, differential tissue expression

Abundant in erythrocytes(红细胞)

Is more specific for D-glucose (Km 1.5 mM) than for D-mannose (Km 20 mM) or for D-galactose (Km 30 mM)

Immediately after import, glucose is phosphorylated to Glu-6-P, Why?

- Maintaining gradient for further rapid glucose import

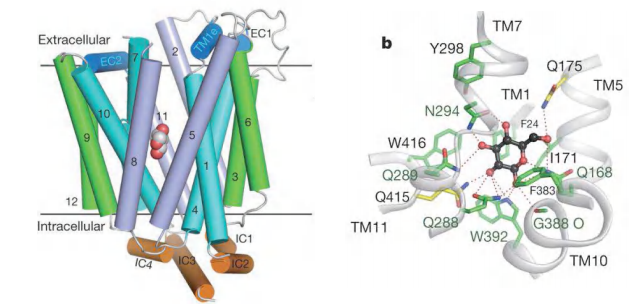

(2) From Structure to Function

Features

- 12 transmembrane segments and a unique intracellular four-helix domain.

- Captured in an outward-facing, partly occluded conformation.

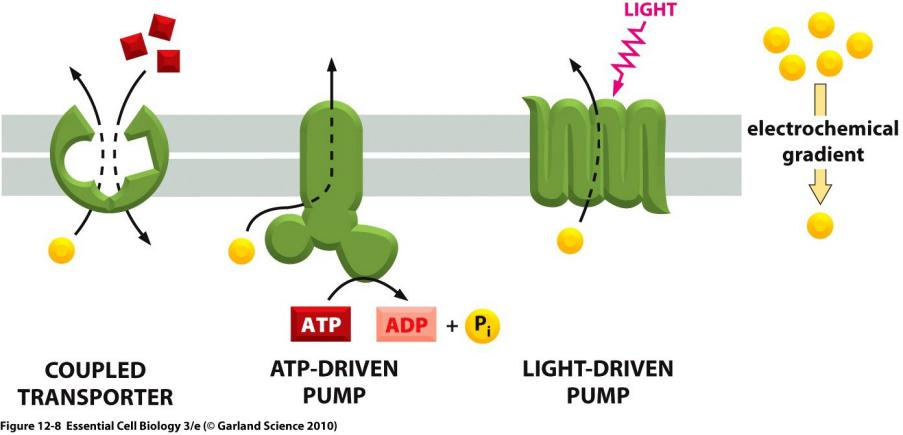

3. Active

When transport against an electrochemical gradient

- Active transport always requires some sort of energy.

Cells carry out such active transport in three main ways

- Coupled transporters harness the energy stored in concentration gradients to couple the uphill transport of one solute across the membrane to the downhill transport of another.

- Active Transport Can Be Driven by Ion-Concentration Gradients

- Some transporters simply passively mediate the movement of a single solute from one side of the membrane to the other at a rate determined by their $V_{max}$ and $K_m$; they are called uniporters.

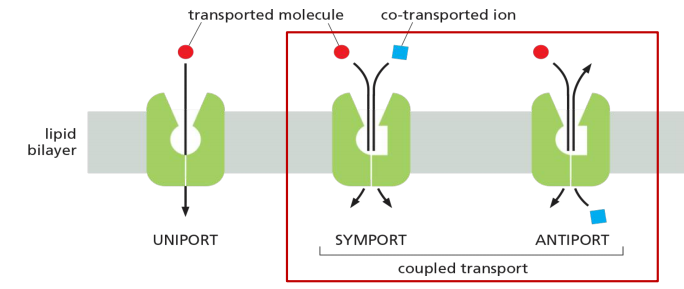

- Others function as coupled transporters, in which the transfer of one solute strictly depends on the transport of a second. Coupled transport involves either the simultaneous transfer of a second solute in the same direction, performed by symporters (also called co-transporters), or the transfer of a second solute in the opposite direction, performed by antiporters (also called exchangers)

- ATP-driven pumps couple uphill transport to the hydrolysis of ATP.

- Light- or redox-driven pumps, which are known in bacteria, archaea, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, couple uphill transport to an input of energy from light, as with bacteriorhodopsin (discussed in Chapter 10), or from a redox reaction, as with cytochrome c oxidase

Coupled transporters

Two main types: symporter and antiporter

- Uniport: transport a single type of molecule “down” its gradient. E.g. glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1).

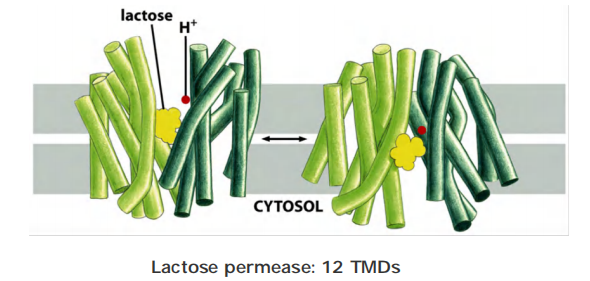

- Symport: couple the movement of one type of molecule against its gradient in the same direction. E.g. lactose permease.

- Antiport: couple the movement of one type of molecule against its gradient in the opposite direction. E.g. Na+/H+ exchanger

(1) Symporter

Each Na+-driven symporter is specific for importing a small group of related sugars or amino acids into the cell

Features

- Energy for the transport is stored in electrochemical gradients.

- Symporter couple the Na+ or H+ gradient with the transport of other molecules (sugars).

- Transport can only occur if “both” molecules are present.

- Eukaryotic cells mainly use Na+ as a primary co-transporting ion

- Bacteria and yeast or subcellular organelles in animal cells mainly use H+ as a primary co-transporting ion

Examples

- sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1 (SGLT1) - Use Na+ gradient

- lactose permease - Use H+ gradient

Glucose–Na+ Symporter (SGLT1)

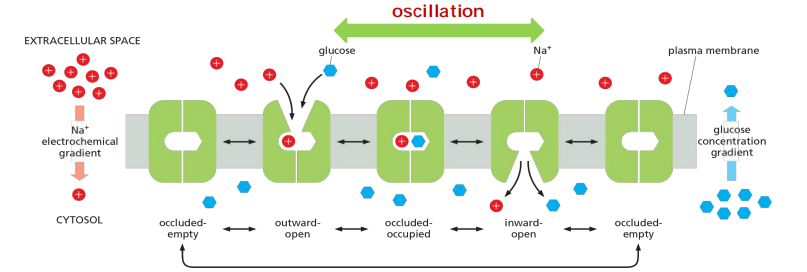

SGLT1 is a symporter: Glucose transport is driven by a [Na+] gradient.

It uses electrochemical gradient of Na+ to transport glucose into cell.

- Binding of Na+ and glucose is cooperative.

- The transition to the occluded state occurs only when both Na+ and glucose are bound

- The overall result is the net transport of both Na+ and glucose into the cell.

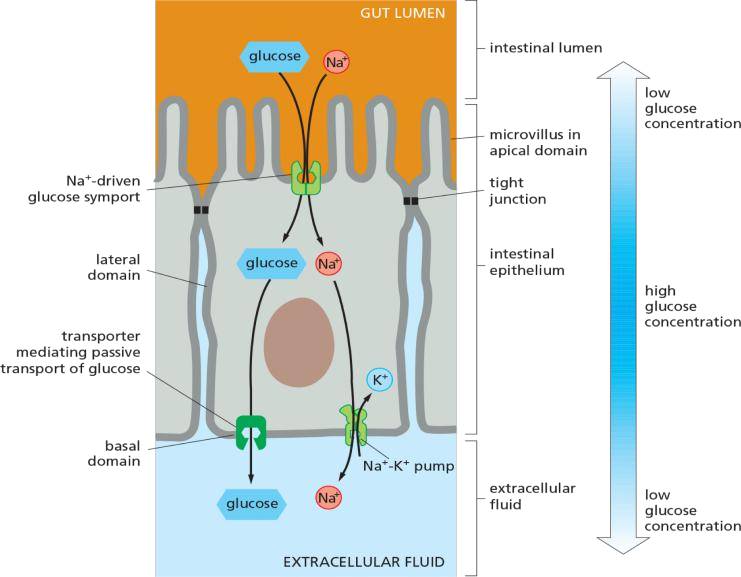

Transcellular transport of glucose occurs via distinct glucose transporters

SGLT1 mediated transport from gut(肠子)to intestinal epithelium cell (肠上皮细胞)

Transcellular transport of glucose: glucose is transferred through a cell.

Principle: “functionally distinct” transporters are differentially distributed in the plasma membrane

An Asymmetric Distribution of Transporters in Epithelial Cells Underlies the Transcellular Transport of Solutes

In epithelial cells, such as those that absorb nutrients from the gut, transporters are distributed nonuniformly in the plasma membrane and thereby contribute to the transcellular transport of absorbed solutes

Na+-linked symporters located in the apical (absorptive) domain of the plasma membrane actively transport nutrients into the cell, building up substantial concentration gradients for these solutes across the plasma membrane. Uniporters in the basal and lateral (basolateral) domains allow the nutrients to leave the cell passively down these concentration gradients.

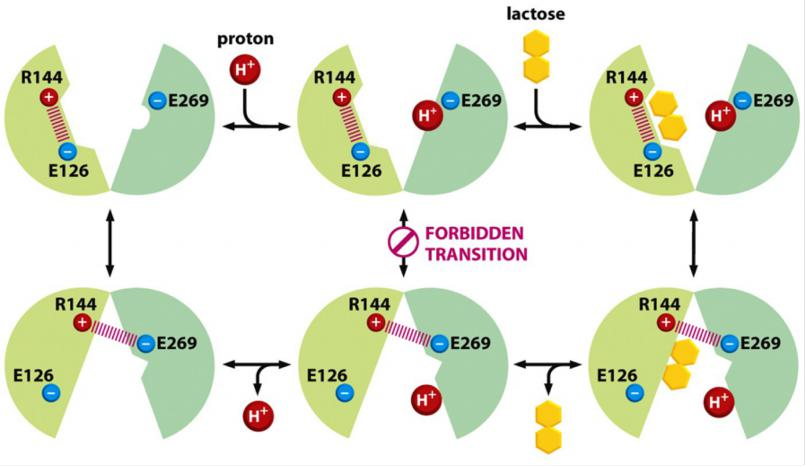

Lactose permease in E. coli

Lactose transport in E. coli is driven by H+ symport.

Lactose permease transport- at the molecular level

Arginine (R) 144 forms bond with glutamic acid (E) 126, leaving glutamic acid (E)269 free to accept a proton (H+) and together with lactose binding a conformational exchange occurs that triggers transport.

After the change, R144 forms now a bond with E269 which destroys the binding site for lactose, triggering release, and after the proton is also released, the molecule flips back to the starting position, exposing the bind-in sites (R144 forms the bond with E126)…..

(2) Antiporter

Antiporter is a way for cells to regulate cellular pH

pH of cells and intracellular compartments is strictly controlled, but pH greatly differs between compartments:

- Cellular (cytosol) pH : ~7.2

- Lysosomal pH: ~5.0

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) PH: ~7.2

Two options to alkalize (up) regulate cytosolic pH:

- Option 1: Export of H+ out of the cell

- Option 2: Neutralization of H+ in the cytosol by HCO3- import

$$

HCO3^- + H^+ → H_2O + CO_2

$$

Most cells have one or more types of Na+-driven antiporters in their plasma membrane that help to maintain the cytosolic pH at about 7.2

Option 1: Export of H+ out of the cell

One of the antiporters that uses the first mechanism is a Na+–H+ exchanger, which couples an influx of Na+ to an efflux of H+

Na+-H+ exchanger: coupled influx of Na+ to the efflux of H+

- The driving force for this antiport is [Na+] gradient across the PM.

- Regulation: activity of the Na+-H+ exchanger is increased upon lower pH in cytosol

Option 2: Neutralization of H+ in the cytosol by HCO3- import (HCO3- + H+ → H2O + CO2)

Another, which uses a combination of the two mechanisms, is a Na+-driven Cl––HCO3– exchanger that couples an influx of Na+ and HCO3– to an efflux of Cl– and H+ (so that NaHCO3 comes in and HCl goes out).

The Na+-driven Cl––HCO3– exchanger is twice as effective as the Na+–H+ exchanger: it pumps out one H+ and neutralizes another for each Na+ that enters the cell. If HCO3– is available, as is usually the case, this antiporter is the most important transporter regulating the cytosolic pH. The pH inside the cell regulates both exchangers; when the pH in the cytosol falls, both exchangers increase their activity.

Na+-driven Cl^-^-HCO3^-^ exchanger:

- coupled influx of Na+ and HCO3- to efflux of Cl- and H+

- usually, NaHCO3 goes in and HCl goes out

- twice as effective as the Na+-H+ exchanger because for each imported Na+, one H+ is neutralized in the reaction and a second H+ is exported.

- Regulation: activity of the Na+-driven Cl–HCO3- exchanger is increased upon lower PH in cytosol.

Na+-independent Cl^-^-HCO3^-^ exchanger acidify (pH goes down)

A Na+-independent Cl––HCO3– exchanger adjusts the cytosolic pH in the reverse direction.

The exchanger’s activity increases as the cytosol becomes too alkaline. The movement of HCO3– in this case is normally out of the cell, down its electrochemical gradient

A Na+-independent Cl––HCO3– exchanger in the membrane of red blood cells (called band 3 protein—see Figure 10–38) facilitates the quick discharge of CO2 (as HCO3–) as the cells pass through capillaries in the lung.

ATP-driven H+ pumps are used to control the pH of many intracellular compartments.

- coupled export of HCO3- to influx of HCl

- Regulation: activity of the Na+-independent Cl–HCO3- exchanger is increased upon higher PH in cytosol.

Such ion-driven coupled transporters as just described are said to mediate secondary active transport. In contrast,

ATP-driven pumps are said to mediate primary active transport because in these the free energy of ATP hydrolysis is used to directly drive the transport of a solute against its concentration gradient.

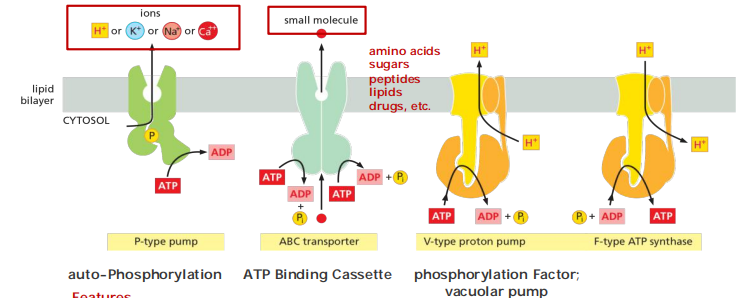

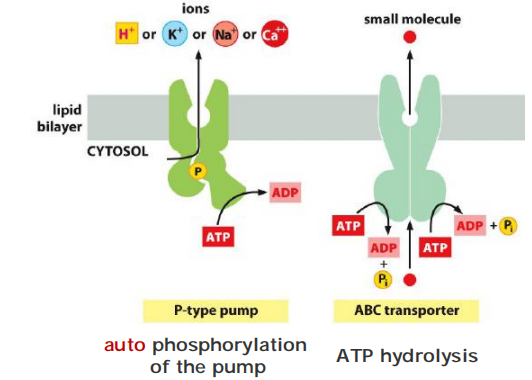

ATP-pumps: molecular machines

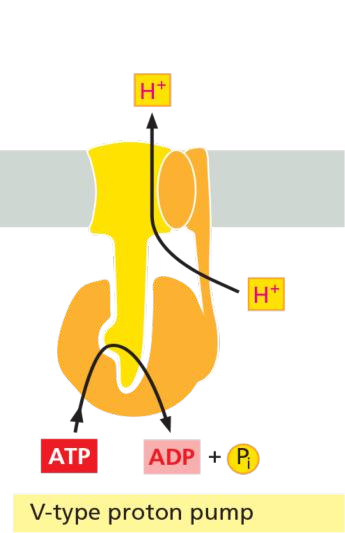

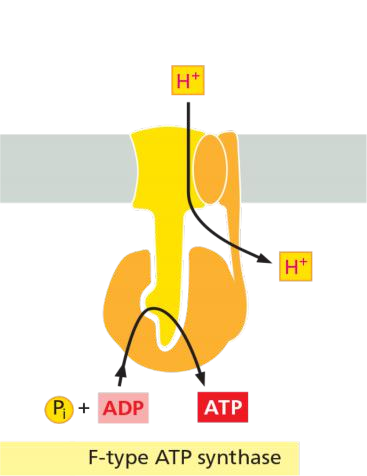

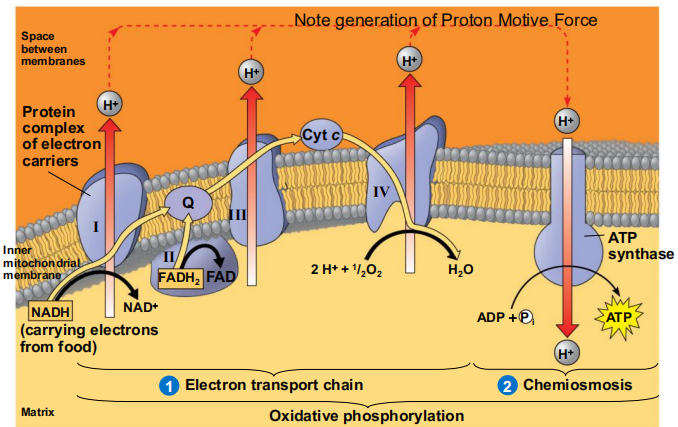

Four types of pumps: P-type, V-type, ABC transporter, and F-type.

ATP-driven pumps are often called transport ATPases because they hydrolyze ATP to ADP and phosphate and use the energy released to pump ions or other solutes across a membrane

- P-type pumps are structurally and functionally related multipass transmembrane proteins. They are called “P-type” because they phosphorylate themselves during the pumping cycle. This class includes many of the ion pumps that are responsible for setting up and maintaining gradients of Na+, K+, H+, and Ca2+ across cell membranes.

- ABC transporters (ATP-Binding Cassette transporters) differ structurally from P-type ATPases and primarily pump small molecules across cell membranes.

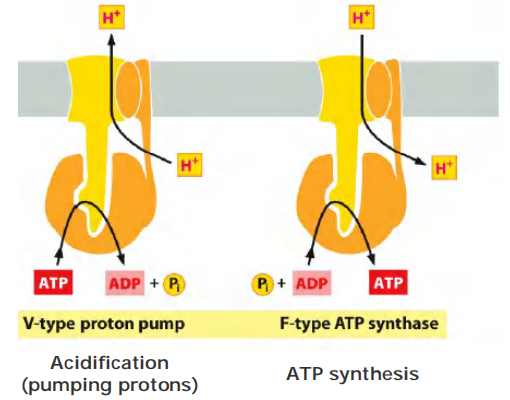

- V-type pumps are turbine-like protein machines, constructed from multiple different subunits. The V-type proton pump transfers H+ into organelles such as lysosomes, synaptic vesicles, and plant or yeast vacuoles (V = vacuolar), to acidify the interior of these organelles

Structurally related to the V-type pumps is a distinct family of F-type ATPases, more commonly called ATP synthases

- instead of using ATP hydrolysis to drive H+ transport, they use the H+ gradient across the membrane to drive the synthesis of ATP from ADP and phosphate

Features

- ATP-pumps are active transporters, using ATP as energy source

- ATP-pumps have ATPase activity (ATP hydrolysis)

- some ATP-pumps have also ATP synthesis activity (ATP synthases)

- Couple ATP hydrolysis with transport

- ATP-binding sites ( > = 1) is on the cytosolic portion of these pump.

- ATP is not transported!

(1) Examples of ATP-pumps

Four types of pumps: P-type, F-type, V-type and ABC transporter

- P-type pumps: Ca2+ pump; Na+-K+ pump

- F-type pumps: ATP-synthase/ATPase

- V-type pumps: VHA ATPase

- ABC transporters: Multidrug resistance protein (MDR)

(2) The P-type ATP-pumps

Features:

- Structurally and functionally related multi-transmembrane proteins

- They phosphorylate themselves during the pumping cycle.

- Many P-type pumps are responsible for generating and maintaining gradients of Na+, K+, H+ and Ca2+ across cell membranes:

- H+ pump in plants and fungi

- Na+/K+ pump in higher organism, such in the plasma membrane

- H+/K+ pump in stomach

- Ca2+ pump

- (ER membrane in all eukaryotic cells, ER内部的Ca+浓度远高于基质内浓度,当需要的时候,通过releasing channel释放到基质)

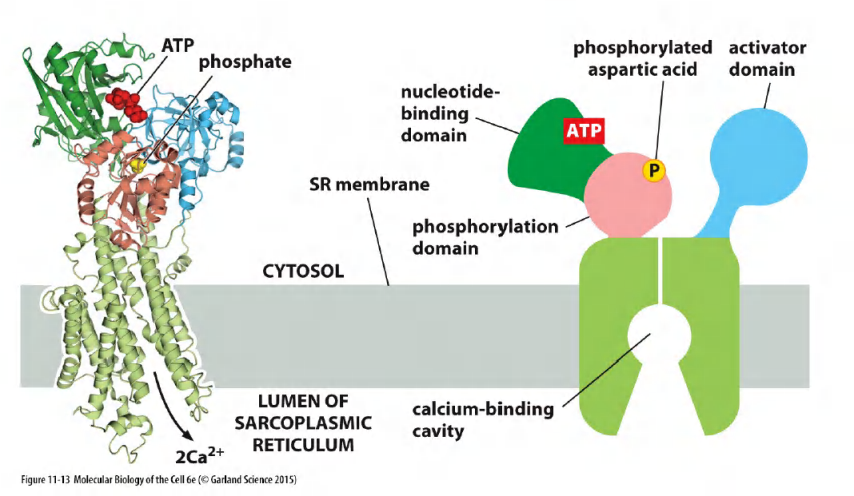

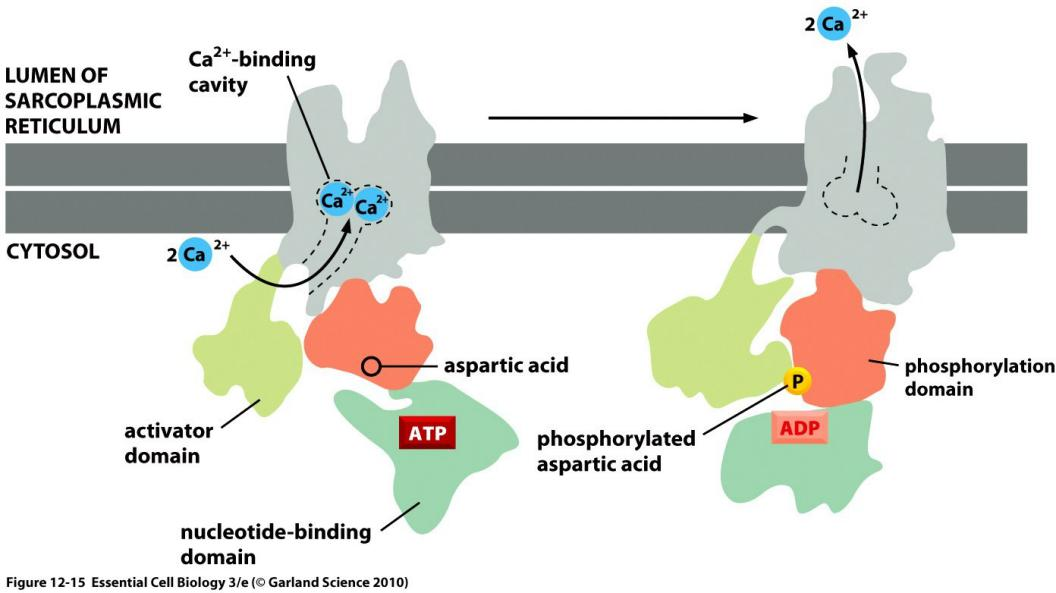

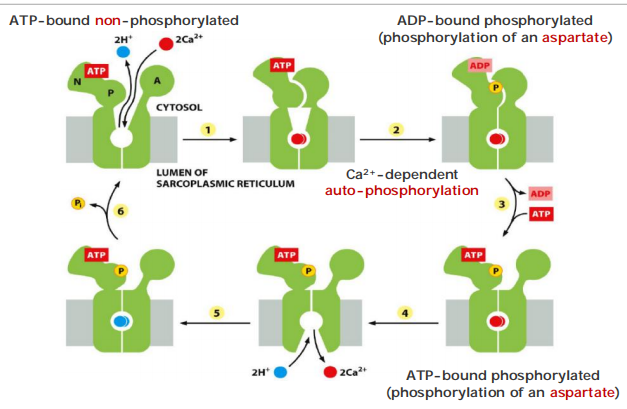

Calcium pumps / Ca2+ ATPase

Ca2+ transporters that actively pump Ca2+ out of the cell help maintain the gradient. One of these is a P-type Ca2+ ATPase; the other is an antiporter (called a Na+–Ca2+ exchanger) that is driven by the Na+ electrochemical gradient (discussed in Chapter 15).

When an action potential depolarizes the muscle cell plasma membrane, Ca2+ is released into the cytosol from the SR through Ca2+-release channels, stimulating the muscle to contract (discussed in Chapters 15 and 16)

Ca2+ is an important messenger in signal transduction.

The goal is to keep calcium concentration low

They all have similar structures, containing 10 transmembrane α helices connected to three cytosolic domains (Figure 11–13)

Features

- Locate in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in all eukaryotic cells

- Represents up to 90% of the membrane protein in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR, ER) of skeletal muscle cells

- Possesses 10 transmembrane $\alpha $-helices (for pumping)

“pumping” is due to conformational changes and movement of $\alpha$-helices

What is the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+? What about extracellular levels?

The goal is to keep calcium concentration low.

The pumping cycle of the Ca2+ pump: ATP-driven antiport of Ca2+/H+

Transient “self-phosphorylation” is characteristic for all P-type pumps!

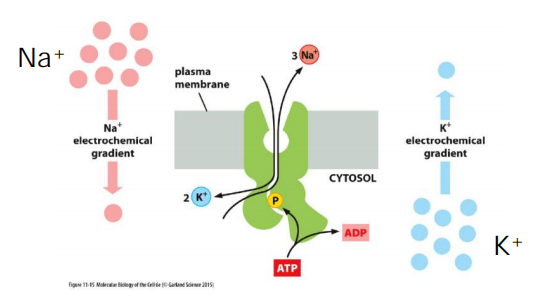

The Na+-K+ pump (Na+-K+ ATPase) on the Plasma Membrane

In the plasma membrane of animal cells, Na+ is the usual co-transported ion because its electrochemical gradient provides a large driving force for the active transport of a second molecule.

The Na+ that enters the cell during coupled transport is subsequently pumped out by an ATP-driven Na+-K+ pump in the plasma membrane

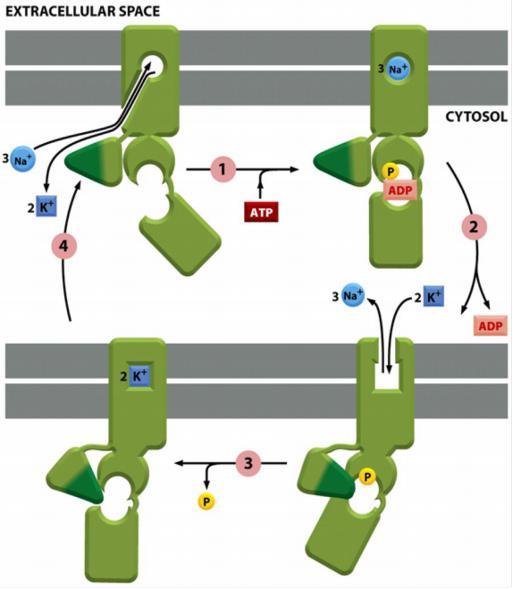

A Na+-K+ pump, or Na+K+ ATPase, found in the plasma membrane of virtually all animal cells maintains these concentration differences. Like the Ca2+ pump, the Na+-K+ pump belongs to the family of P-type ATPases and operates as an ATP-driven antiporter

Since the Na+-K+ pump drives three positively charged ions out of the cell for every two it pumps in, it is electrogenic: it drives a net electric current across the membrane, tending to create an electrical potential, with the cell’s inside being negative relative to the outside

The Na+-K+ ATPase is a major regulator of osmolarity(同渗容摩) and it is an electrogenic pump: export of 3 Na+ vs import of 2 K+.

Generation of an electrical current across the membrane and builds electric potential: negative inside, positive outside.

The pumping cycle of the Na+-K+ pump

Steps:

In the cytosolic surface the non-phosphorylated transporter has high affinity for Na+ ions but only low affinity for K+ ions

ATP binding and hydrolysis causes conformational change and the release of 3 Na+ ions outside.

The phosphorylated transporter has now high affinity for K+ ions but only low affinity for Na+ ions in the exoplasmic surface.

K+ dependent dephosphorylation causes conformational change and release of K+ inside.

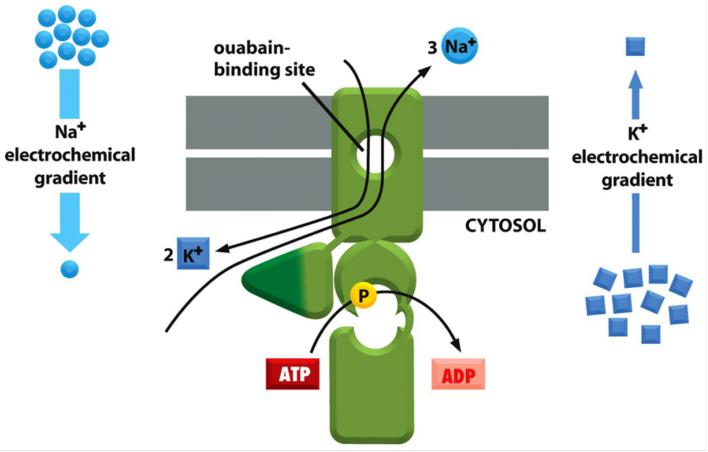

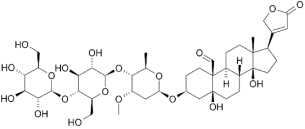

Drugs targeting the Na+-K+ ATPase: the cardio glycosides ouabain(心脏苷哇巴因) and digoxin (地高辛;异羟基洋地黄毒苷原)

Ouabain(乌本(箭毒)苷) (from Strophanthus gratus) :

- specific inhibitor of the Na+-K+ ATPase from plants.

- used as arrow poison for hunting/warfare

- at low concentration: drug against hypotension

Digoxin(地高辛;异羟基洋地黄毒苷原) (from Digitalis lanata):

Binding to the exoplasmic domain, both are specific inhibitors of ATPase activity.

(3) The V-type ATPases (vacuolar) V-ATPases

Features

- Transport only protons, but generally do NOT synthesize ATP for the purpose of acidification rather than energy production.

- Present in all acidic compartments: lysosomes, endosomes and vacuoles in mammals, plants and yeasts.

- Pump protons in the organelle to achieve/maintain low pH levels.

- Structurally similar to F-type transporters.

- They are NOT controlled by auto-phosphorylation

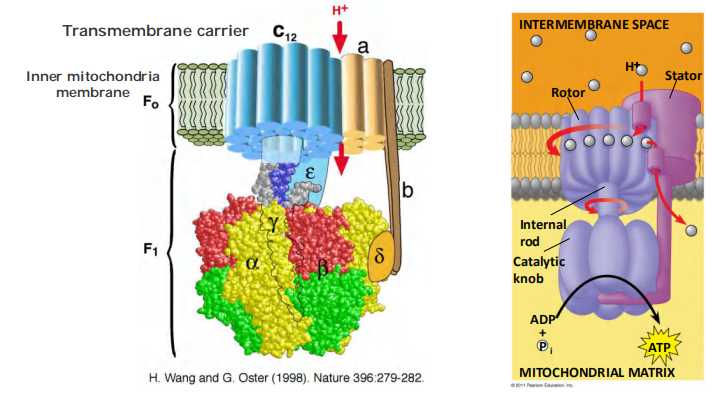

(4) The F-type ATP-pumps: ATP synthases

Features

- Turbine-like(涡轮状) proteins, consist of multiple different subunits.

- Found in the plasma membrane of bacteria, the inner membrane of mitochondria, and in the thylakoid membrane of chloroplast.

- Called ATP synthase because they can catalyze both, synthesis and hydrolysis of ATP.

- They use a H+ gradient across the membrane to drive the synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi.

- They are NOT controlled by auto-phosphorylation.

Reverse-Running H+ Pump

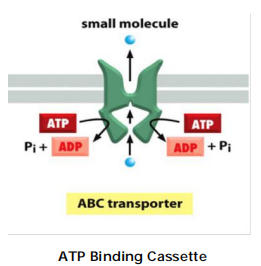

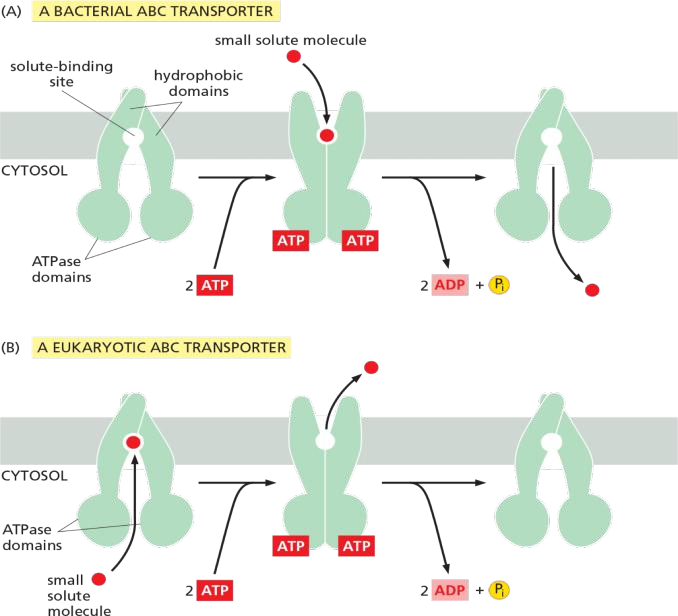

(5) The ABC transporters

so named because each member contains two highly conserved ATPase domains, or ATP-Binding “Cassettes,” on the cytosolic side of the membrane.

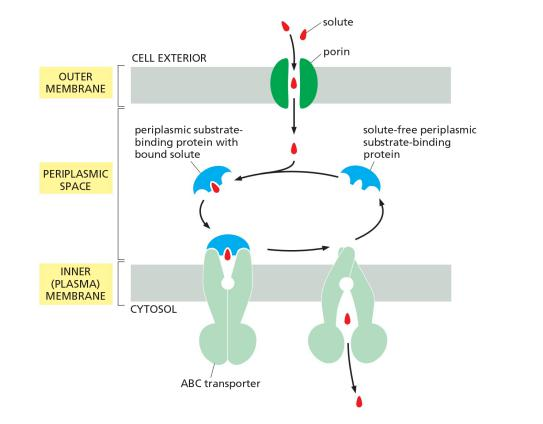

Although each transporter is thought to be specific for a particular molecule or class of molecules, the variety of substrates transported by this superfamily is great and includes inorganic ions, amino acids, mono- and polysaccharides, peptides, lipids, drugs, and, in some cases, even proteins that can be larger than the transporter itself.

Features

Pump small molecules across cell membranes.

In addition, bacteria use ABC transporters to import certain small molecules.

Contain two transmembrane domains and two cytosolic ATP binding domains (ATP-Binding Cassettes)

ATP binding leads to dimerization of ATP–cassettes.

ATP hydrolysis leads to the dimer dissociation.

Conformational changes leads to transport of small molecules.

ABC transporters are important: In E. coli, 5% of all bacteria genes encode for ABC transporter.

ABC transporters are clinically important drug targets

The transport cycle of a typical ABC transporter

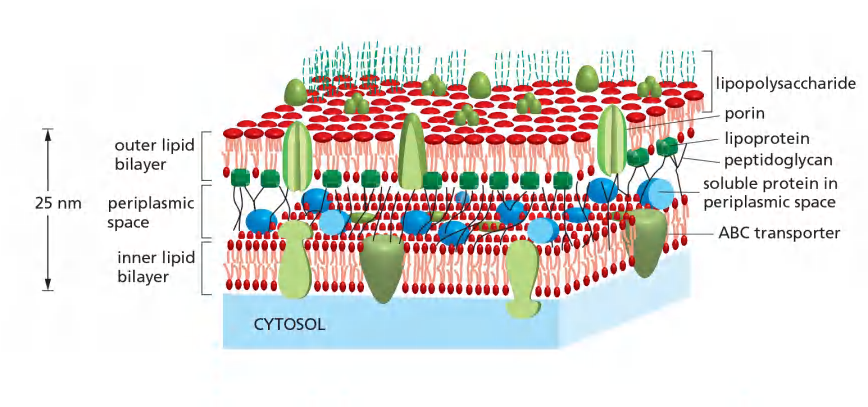

The function of ABC transporter in prokaryotes , e.g. E. coli

Gram (-) bacteria : inward transport / uptake

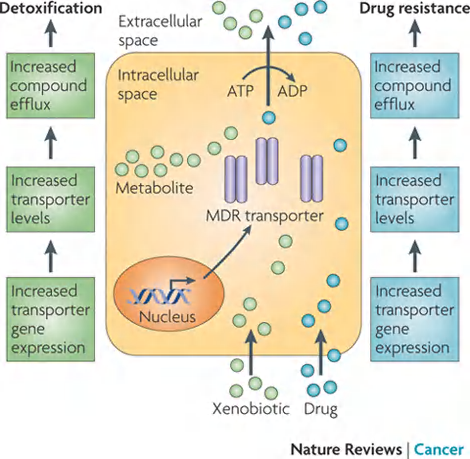

Eukaryotic ABC transporter: multidrug resistance (MDR)

the multidrug resistance (MDR) protein, also called P-glycoprotein

These cells pump drugs out of the cell very efficiently and are therefore relatively resistant to the drugs’toxic effects

Example 1: The multidrug resistance (MDR) protein overexpressed in many drug resistant cancer cells.

MDR:

- The first eukaryotic ABC transporters identified.

- The ability to pump hydrophobic drugs out of the cytosol, and therefore relatively resistant to the drugs.

- Elevated MDR levels in human cancer cells make the cells resistant to a variety of cytotoxic drugs used in cancer chemotherapy.

- Selection for cancer cells with resistance to one drug can thereby lead to resistance to a wide variety of anticancer drugs.

- Use 2 ATP at one time.

The resistant P. falciparum have amplified a gene encoding an ABC transporter that pumps out the chloroquine.

In most vertebrate cells, an ABC transporter in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (named transporter associated with antigen processing, or TAP transporter) actively pumps a wide variety of peptides from the cytosol into the ER lumen

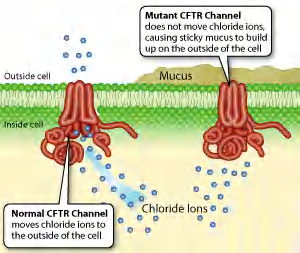

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR).

another member of the ABC transporter family is the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein (CFTR), which was discovered through studies of the common genetic disease cystic fibrosis.

In contrast to other ABC transporters, ATP binding and hydrolysis in the CFTR protein do not drive the transport process. Instead, they control the opening and closing of a continuous channel

Thus, some ABC proteins can function as transporters and others as gated channels.

CFTR:

- CFTR is an ABC transporter that regulates ion concentrations in the extracellular fluid especially in the lungs.

- CFTR regulates open and close of a continuous Cl- channel and mutation in CFTR leads to cystic fibrosis (囊胞性纤维症).

- ATP binding and hydrolysis does NOT drive the transport. They control open/close of a continuous channel, resulting in passive conduct for Cl– to move down its electrochemical gradient.

- Thus, some ABC proteins can function as transporters and others as gated channels!!!

Example 3: Chloroquine (氯喹(疟疾的特效药的一种)) resistance in malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum (疟原虫)

The protozoa has enhanced level of chloroquine ABC transporters and therefore has resistance to chloroquine.

The resistant have amplified the gene encoding an P. falciparum ABC transporter that pumps out the chloroquine.

(6) Comparisons

P-type pumps vs. ABC transporters

Self-phosphorylation

V-type pumps vs F-type pumps

Different purpose: acidification vs ATP synthesis

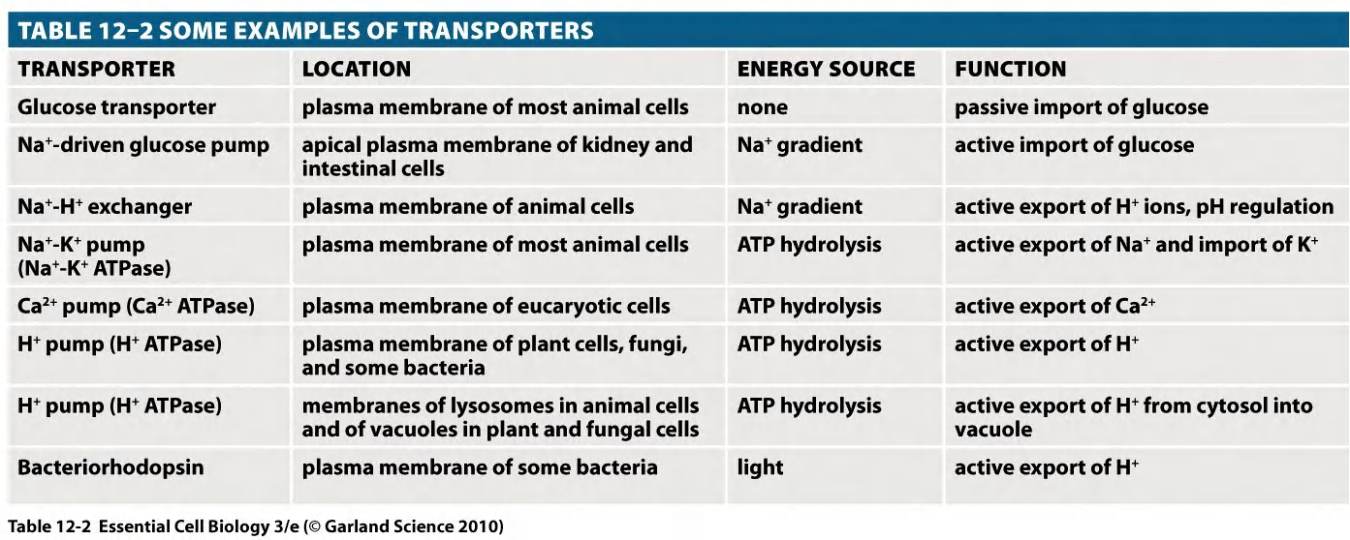

(7) Some examples of transporters

(8) Summary: Transporters

Features: Each transporter has individual biochemical properties:

- one or more specific binding sites for its solute

- a characteristic V

max - a characteristic affinity, K

m - Binding and transport is reversible.

- Binding can be competitively or non-competitively inhibited.

- Transport is selective for only one single or a group of closely related molecules.

- Transport rate is much higher than simple diffusion.

- Hydrophobicity and size of solutes does not matter.

三、Channels

Overview

Features:

- Channel proteins form hydrophilic pores across membranes

- Facilitate molecule movement only “down” the gradient

- Molecule selectivity

- Low binding affinity

- high transport capacity: 10^7^ to 10^8^ ions per second (highly efficient)

- Channels are not coupled to an energy source - always passive transport!

- Gap junctions (connection between two neighboring cells) are found in virtually all animals

- Ion channels are ion-selective and fluctuate between “open” and “closed” states (e.g. K+ channel)

- water channels (aquaporins)

Ion Channels

For transport efficiency, ion channels have an advantage over transporters,

As discussed earlier, however, channels cannot be coupled to an energy source to perform active transport, so the transport they mediate is always passive (downhill).

Thus, the function of ion channels is to allow specific inorganic ions—primarily Na+, K+, Ca2+, or Cl–—to diffuse rapidly down their electrochemical gradients across the lipid bilayer

1. overview

Features

- Highly selective, >100 types have been described thus far

- Transport ions down the gradient.

- Tight control in its open and close forms (Fluctuation!).

- Transport with a high efficiency: 100 million ions per second (that is 100,000 times faster than a channel)

- Are important for muscle and nerve cell function

- Control of opening/closing is termed “gating” → “gated” channels

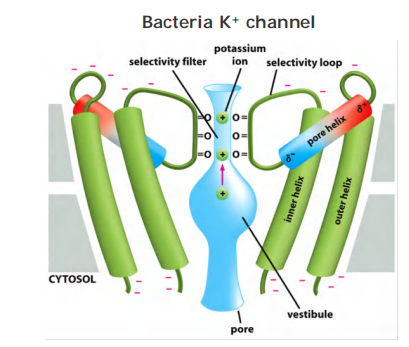

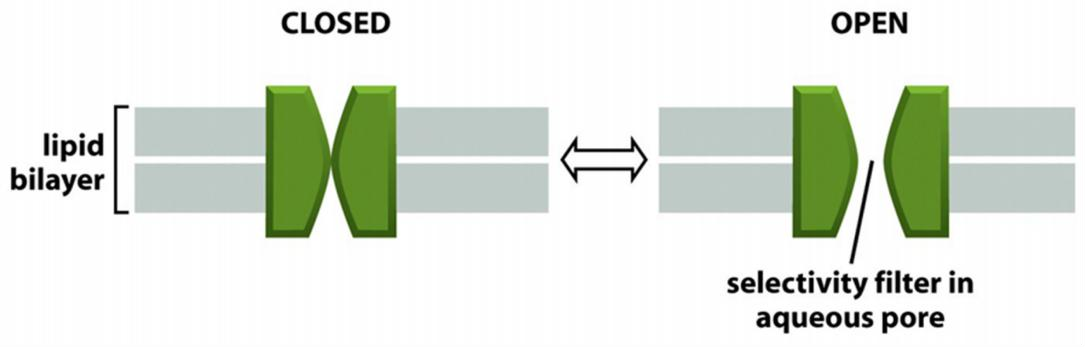

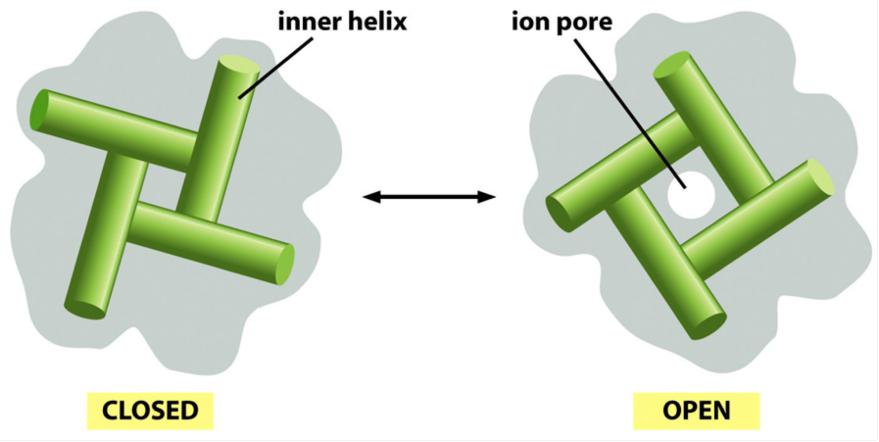

2. selectivity

Select ions on the basis of size and charge

Ion filers facilitate the selectivity of ions

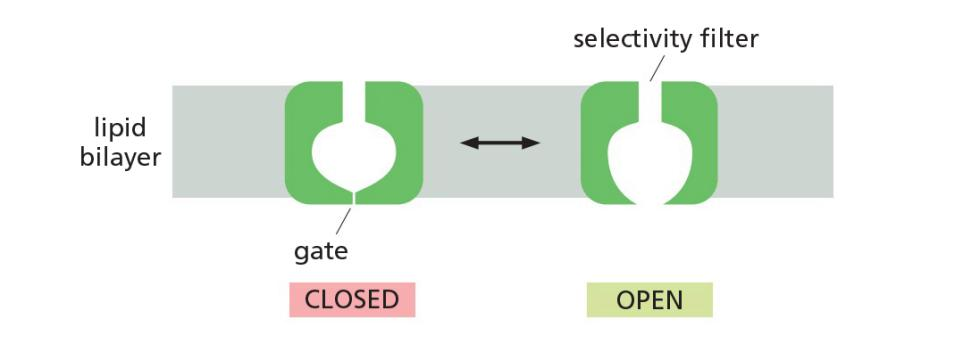

Differ from simple pores also because channels have two states, open and closed

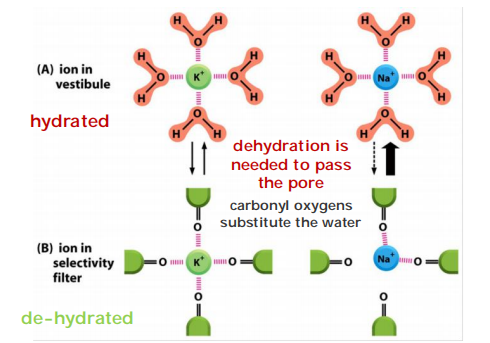

How ion channels can be highly selective?

ion selectivity, permitting some inorganic ions to pass, but not others.

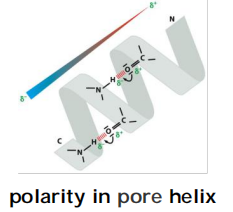

The permeating ions have to shed most or all of their associated water molecules to pass, often in single file, through the narrowest part of the channel, which is called the selectivity filter; this limits their rate of passage

Selectivity: Carbonyl oxygen lines the wall of the selectivity filter and form binding sites for dehydrated K+ ions

Only TWO out of the FOUR subunits with two TMD (Trans-membrane domain)s are shown.

They possess negatively charged amino acids at entrance. That attracts cations and repels anions (selective for cations)

The K+ channel conducts K+ 10,000 fold better than Na+; Na+ is smaller than K+, how can one be too small to sneak through the pore?

(1) Specificity for K+ is due to the selectivity filter

Sodium ion is too small to interact with all four oxygens (cannot maintain the balance)

3. Regulation

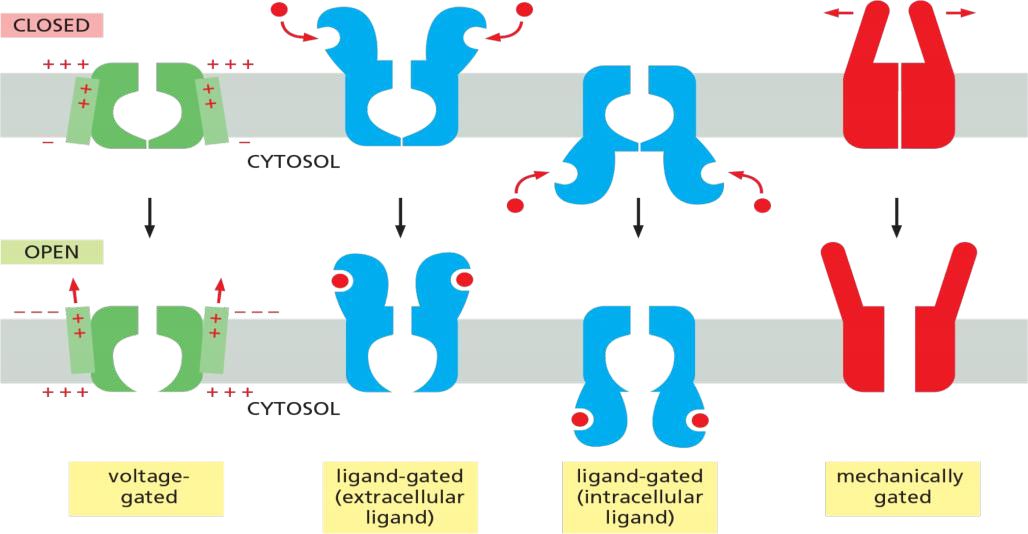

Channels can be regulated to “open” or to “close” (gating):

- Non-gated channels: “open” most of the time

- Gated channels: “open” and “close” in response to signals

“Gated” channels

In most cases, the gate opens in response to a specific stimulus

As shown in Figure 11–22, the main types of stimuli that are known to cause ion channels to open are a change in the voltage across the membrane (voltage-gated channels), a mechanical stress (mechanically gated channels), or the binding of a ligand (ligand-gated channels).

- The ligand can be either an extracellular mediator—specifically, a neurotransmitter (transmitter-gated channels)—or an intracellular mediator such as an ion (ion-gated channels) or a nucleotide (nucleotide-gated channels).

In addition, protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation regulates the activity of many ion channels

Model for gating of a bacterial K+ channel

Closing/opening occurs by tilting of the four inner helices.

An important subset of K+ channels opens even in an unstimulated or “resting” cell, and hence these are called K+ leak channels.

- they serve a common purpose: by making the plasma membrane much more permeable to K+ than to other ions, they have a crucial role in maintaining the membrane potential across all plasma membranes,

A membrane potential arises when there is a difference in the electrical charge on the two sides of a membrane

The net efflux of K+ halts when the membrane potential reaches a value at which this electrical driving force on K+ exactly balances the effect of its concentration gradient—that is, when the electrochemical gradient for K+ is zero

The equilibrium condition, in which there is no net flow of ions across the plasma membrane, defines the resting membrane potential for this idealized cell.

- Nernst equation, quantifies the equilibrium condition

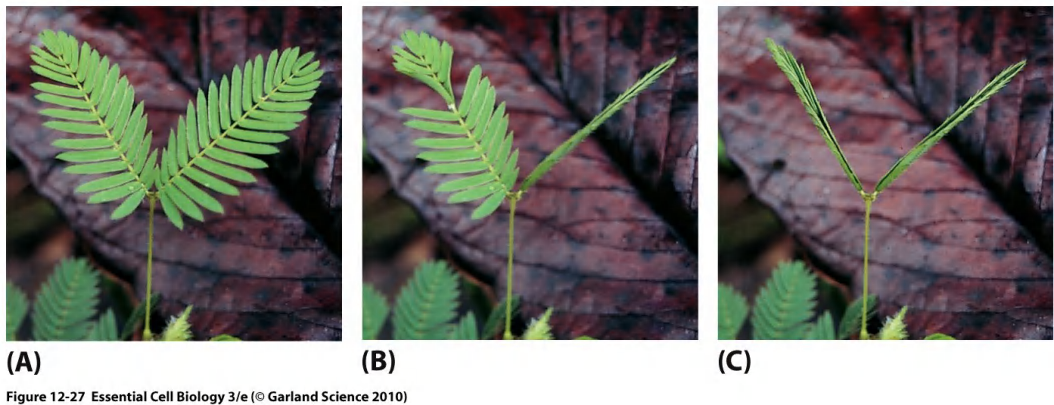

Stress gates

Stress gates react to mechanical changes

Present in inner ear of mammals (go back to the lateral line of fishes)

(1) Example: Mimosa plant

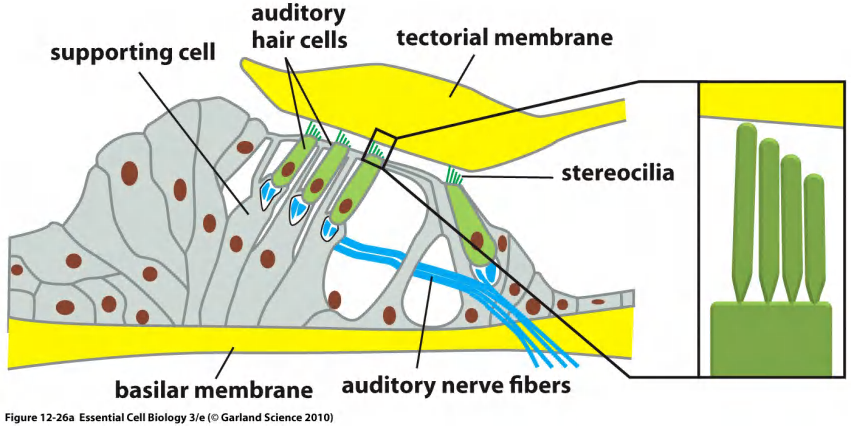

(2) Mechanically-gated channels in the hair cell of the ear

Organ of Corti, the auditory portion of the inner ear

Numerous proteins are known to be capable of responding to such mechanical forces, and a large subset of those proteins has been identified as possible mechanosensitive channels

If the pressure rises to dangerous levels, the cell opens mechanosensitive channels that allow small molecules to leak out.

The mechanosensitive channel of small conductance, called the MscS channel, opens at low and moderate pressures

- The mechanosensitive channel of large conductance, called the MscL channel, opens to over 3 nm in diameter when the pressure gets so high that the cell might burst

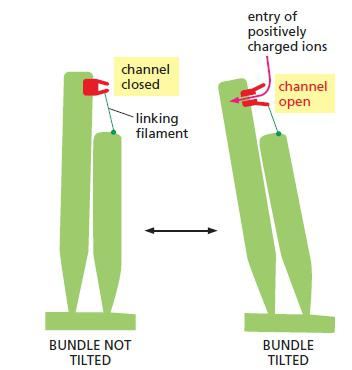

Tilting stretches the filaments, which pulls open mechanically-gated ion channels in the stereocilium plasma membrane, allowing entry of positively charged ions from the surrounding fluid.

The faintest sounds we can hear stretch the filaments about 0.04 nm, which is less than the diameter of a hydrogen ion

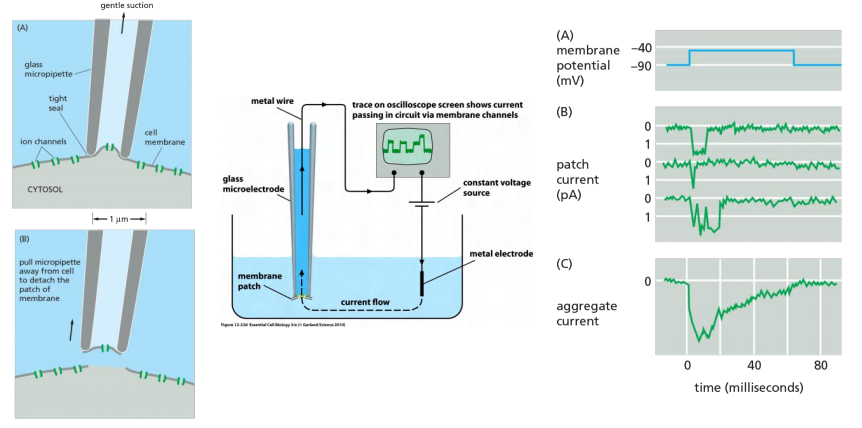

4. Studying ion channels: patch-clamp recording

- Remove a piece of membrane

- Change ion concentration and voltage round this piece

- Measure changes

Patch-clamp

5. Summary: Ion channels

Features:

- Highly selective, >100 types have been described thus far

- Transport ions down the gradient.

- Tight control in its open and close forms. Fluctuation!

- Transport with a high efficiency: 100 million ions per second(that is 100,000 times faster than a channel)

- Are important for muscle and nerve cell function

- Control of opening/closing is termed “gating” → “gated” channels

6. Summary: comparison

Summary: comparison of channels, coupled-transporters, and energy-driven transporter (pumps)

Channels:

- always passive transport

- facilitate molecule movement only “down” the gradient

- low binding affinity

- Efficient, transport capacity 10^7^ to 10^8^ ions per second

Transporters:

- facilitate molecule movement against/“down” the gradient

- bind molecules tightly

- undergo conformational changes

- transport capacity 10^2^ to 10^4^ ions per second

Energy-driven pumps (special types of transporter):

- facilitate molecule movement against the gradient

- requires energy (ATP or light)

- transport capacity 1 to 1000 ions per second

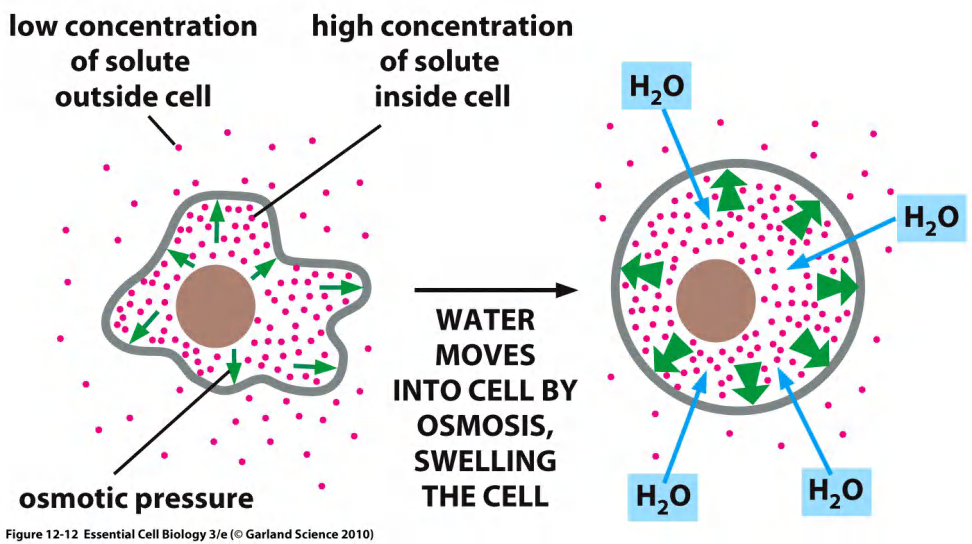

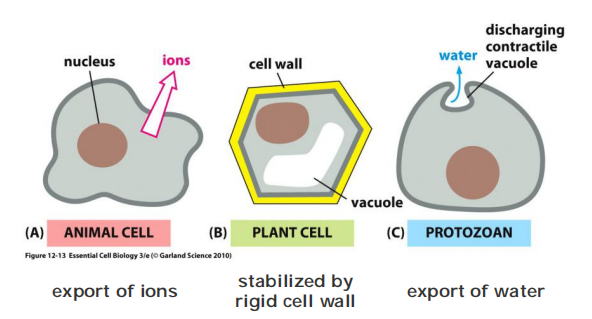

四、Osmotic balance

Transport across the membranes is important!

Cells must maintain appropriate solute concentration to avoid osmotic swelling.

Cells have different ways to prevent osmotic swelling

- export ions

- stabilized by rigid cell wall

- export of water

Definition of Osmotic balance

Osmosis is the default diffusion of ions in a water across semi-permeable membrane

Aquaporin channels facilitate the water movement

Cell walls and contractile vacuoles are used to maintain osmotic pressure, but in animals there is only a sodium-potassium pump (and some other pumps)

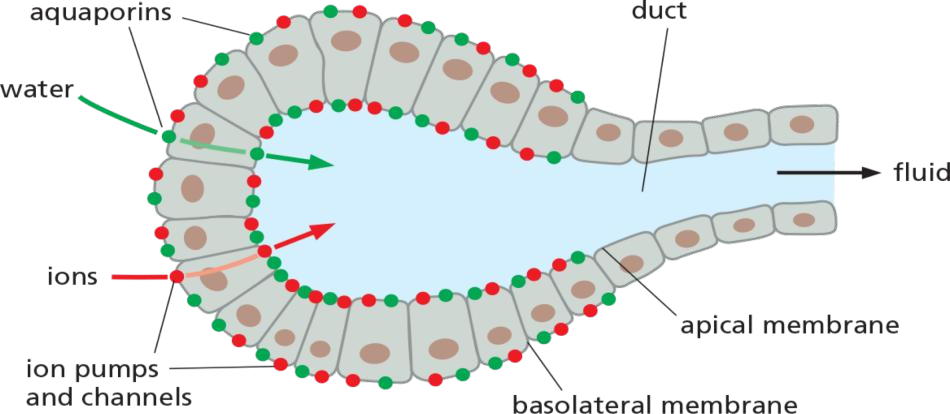

The role of aquaporins in fluid secretion

Abundant in cells that transport water quickly, e.g. kidney epithelial cells and exocrine((腺)外分泌的) glands.

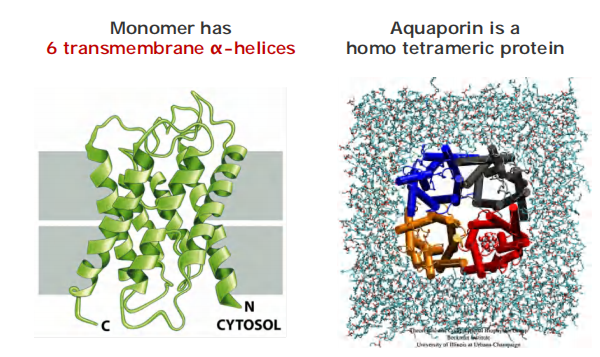

1. Aquaporins increase water permeability of cell membranes

Cells also contain a high concentration of solutes, including numerous negatively charged organic molecules that are confined inside the cell (the so-called fixed anions) and their accompanying cations that are required for charge balance

Because all biological membranes are moderately permeable to water

For most animal cells, however, osmosis has only a minor role in regulating cell volume. This is because most of the cytoplasm is in a gel-like state and resists large changes in its volume in response to changes in osmolarity.

water channels, or aquaporins, embedded in their plasma membrane to allow water to move more rapidly. Aquaporins are particularly abundant in animal cells that must transport water at high rates, such as the epithelial cells of the kidney or exocrine cells that must transport or secrete large volumes of fluids, respectively

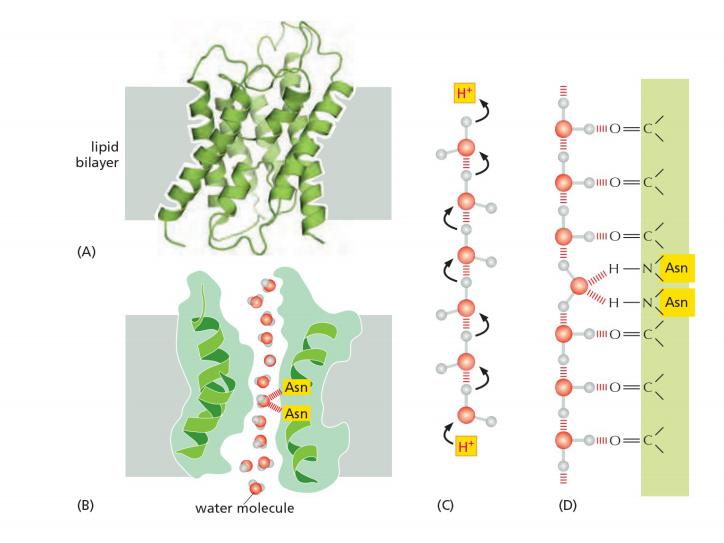

2. How does aquaporin transport water?

A view by cutting the monomer in two halves

The pore is lined with hydrophilic amino acids that provide transient hydrogen bonds to water molecules. These bonds help to line-up water molecules in a single row and orient them as they traverse the membrane.

Inside If water passes through the channel, how is it possible to prevent the flux of H+?

Hydrophobic amino acids line the other side of the pore. The pore is too narrow for any hydrated ion to enter, and the energy cost of dehydrating an ion would be enormous because the hydrophobic wall of the pore cannot interact with a dehydrated ion to compensate for the loss of water.

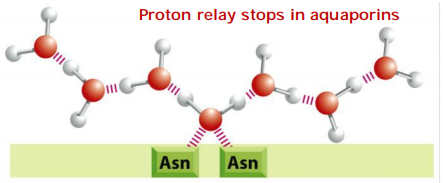

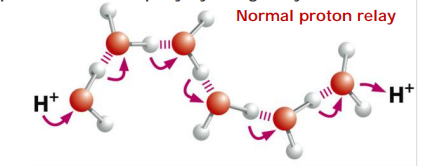

These channels are also impermeable to H+, which is mainly present in cells as H3O+. These hydronium ions diffuse through water extremely rapidly, using a molecular relay mechanism that requires the making and breaking of hydrogen bonds between adjacent water molecules

- This makes it impossible for the “making and breaking” sequence of hydrogen bonds (shown in Figure 11–20C) to get past the central asparagine-bonded water molecule. Because both valences of this central oxygen are unavailable for hydrogen-bonding,

3. How does aquaporin prevent H+ from passing?

In water protons diffuse rapidly by being relayed from one molecule to the next.

In the center of the pore, one water molecule is tethered by two Asparagines.

Tethering occupies both valences(化合价) on it’s oxygen, thus preventing the proton relay!