L12 Nervous System Organization and Biological Clocks

一、The organization and evolution of the nervous systems

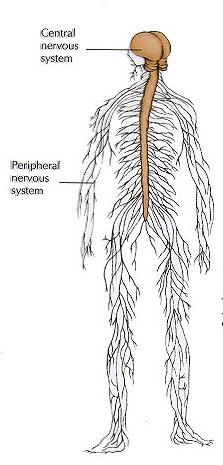

Central nervous system (CNS)

- Interneurons – confined to the CNS

- Sensory neurons – convey info to the CNS

- Motor neurons – convey info out of the CNS

Peripheral Nervous system (PNS)

- Nerve consists of the axons of multiple of neurons bundled together

- Two primary divisions of the vertebrate PNS:

- The somatic nervous system – controls the skeletal muscles to produce voluntary movements

- The autonomic nervous system – controls internal effectors (autonomic efforts) such as glands, cardiac muscles and smooth muscles.

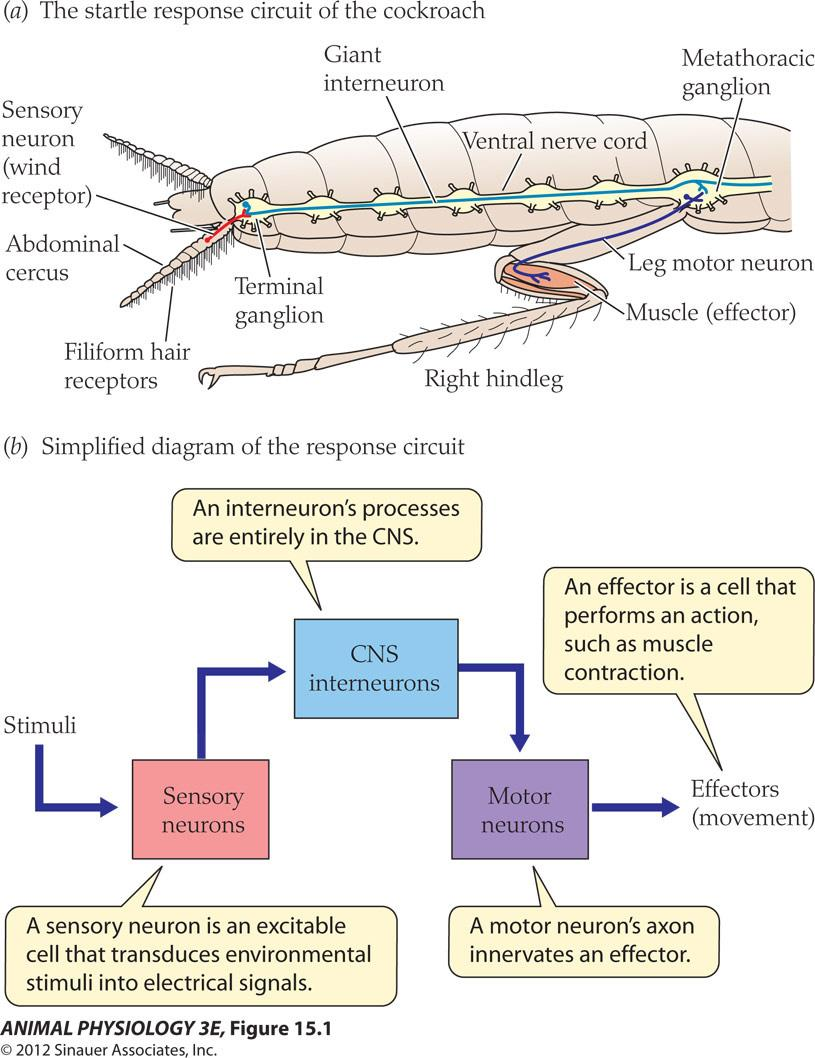

Nervous systems consist of neurons organized into functional circuits

Neurons are organized in circuits in such a way that they can elicit a coordinated, adaptive response of effectors.

Sensory receptor cells (which, like neurons, are excitable cells) transform environmental stimuli into electrical signals.

Central interneurons integrate signals from sensory receptors and other signals arising within the animal, generating an integrated pattern of impulses.

Motor commands are sent out from the CNS to effectors.

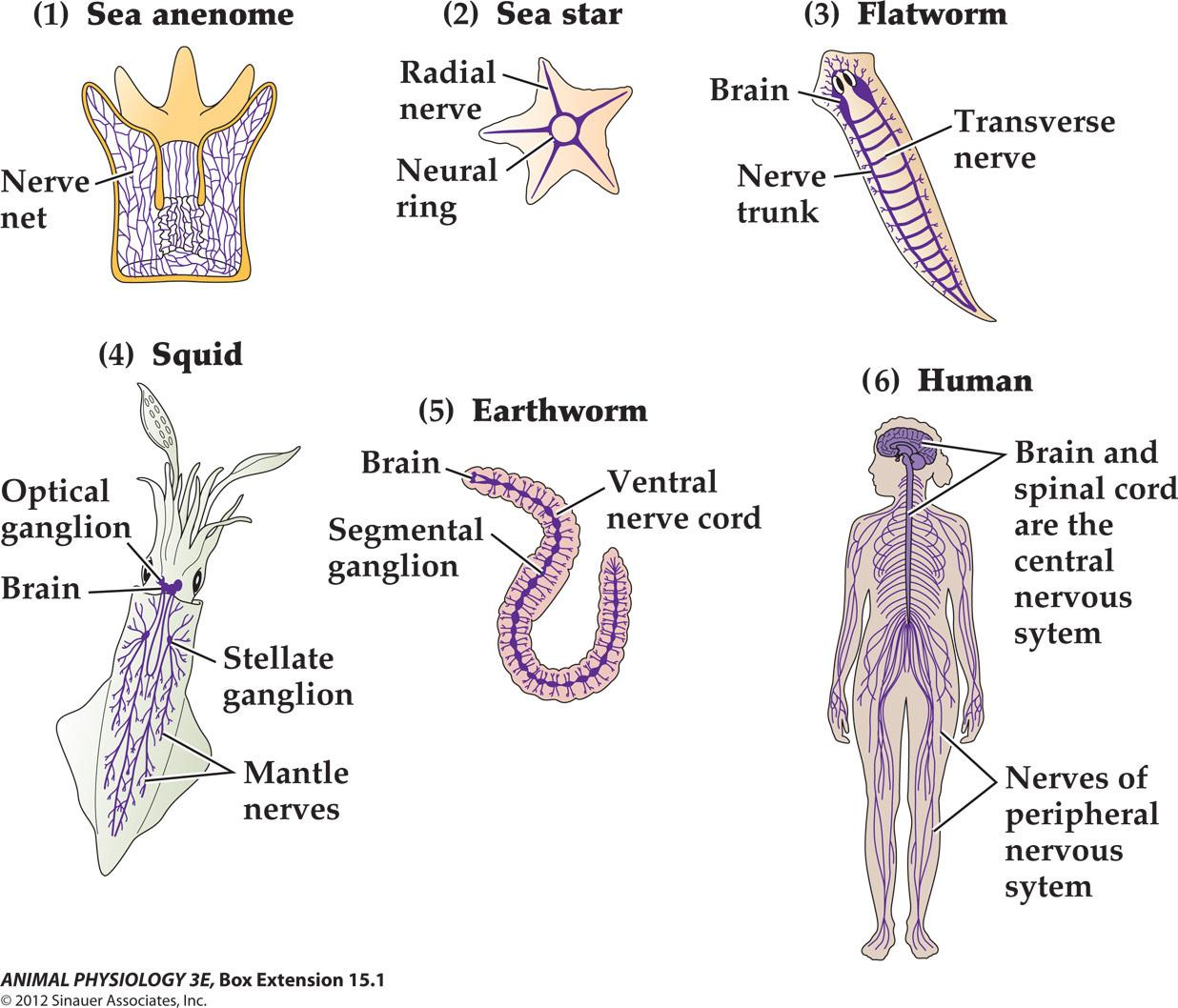

1. Many types of animals have evolved complex nervous systems

Two major trends characterize the evolution of the nervous systems :

Centralization(集中化) : collecting neurons into the central integrating area rather than randomly dispersed

Cephalization(头向集中): concentrating nervous structures and functions to the one end of the system.

Neuronal elements in a nervous system: a neural circuit mediating the cockroach startle responses

- Nervous systems consist of neurons organized into functional Circuits

2. Nervous systems of different phyla

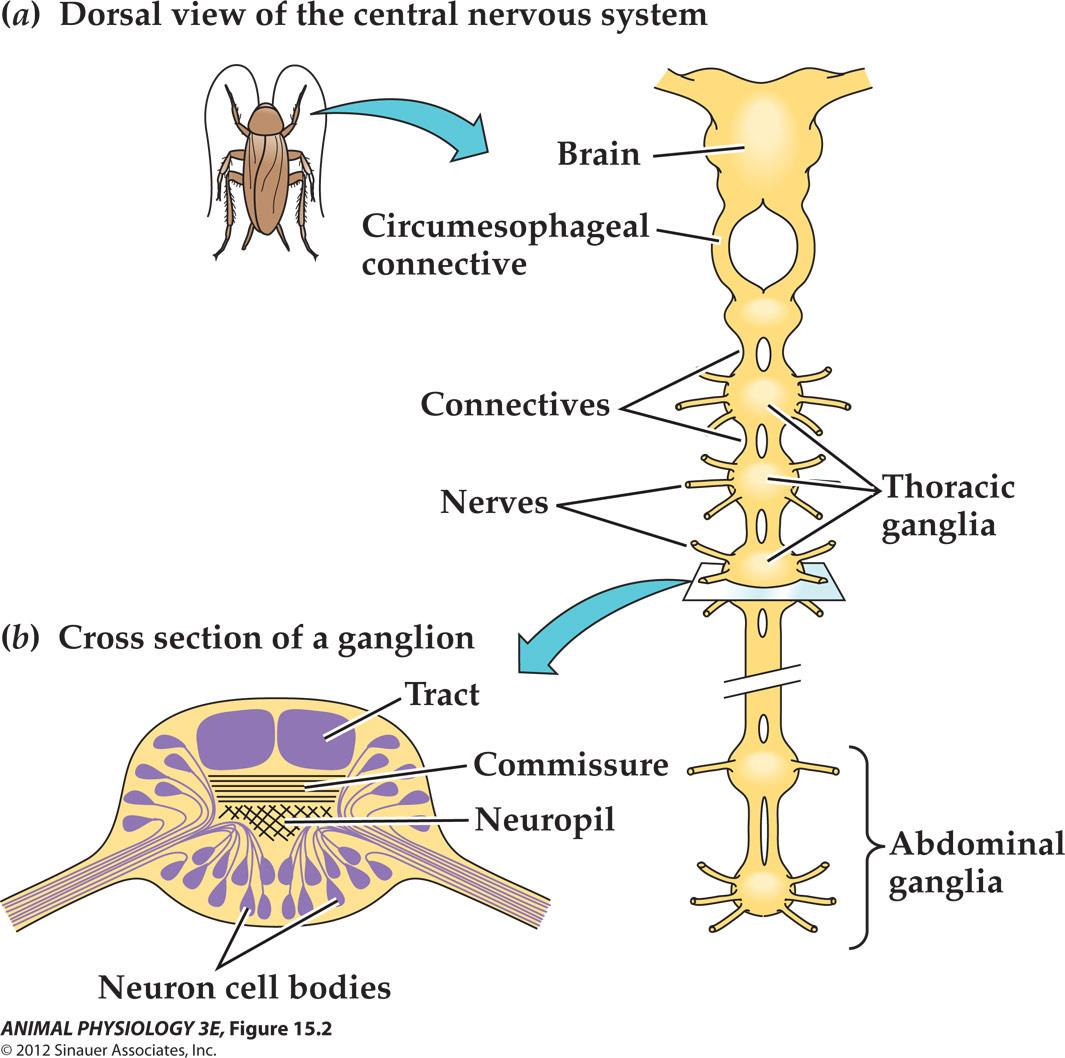

The organization of an arthropod central nervous system

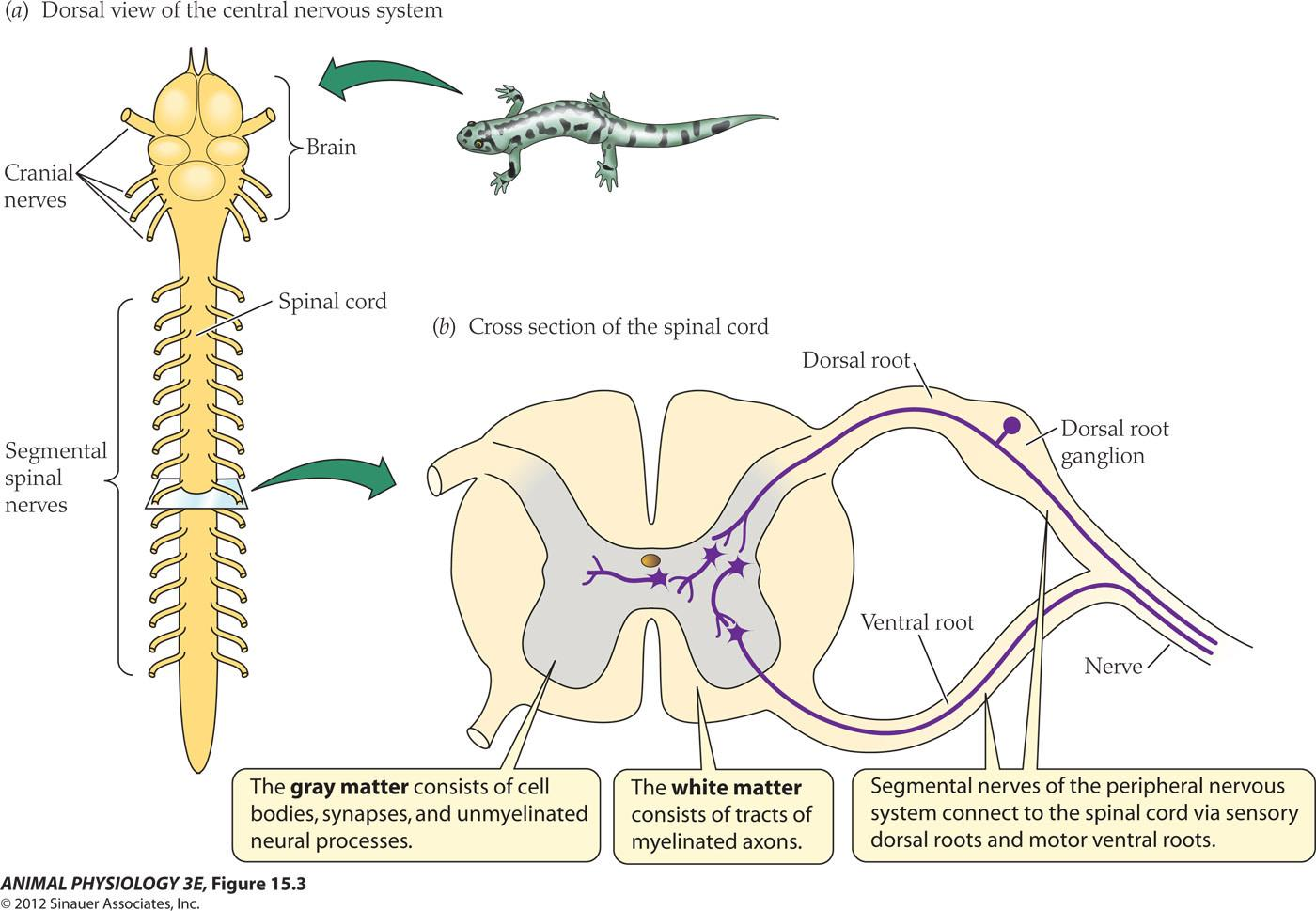

The organization of a vertebrate CNS

- Mammals have 12 pairs of cranial Nerves (I, olfactory; II, optic; III, auditory….X, the vagus nerve)

- The spinal nerves: one pair per vertebra, including both motor and sensory somatic nerves

SUMMARY: The Organization and Evolution of Nervous Systems

Animals have evolved nervous systems with varying degrees of centralization and complexity. There are homologies between the nervous systems of different animal groups.

Most phyla of animals have bilateral symmetry and have evolved central nervous systems (CNSs) that centralize control functions. Sensory neurons convey information into the CNS, and motor neurons convey outward commands to effectors. CNSs usually have some degree of cephalization (concentration of neural structures into a clear anterior brain).

Arthropods have a ganglionic nervous system, one major form of nervous system organization. The arthropod CNS is a ventral ladderlike chain of segmental paired ganglia joined by connectives. A vertebrate CNS, in contrast, is a continuous column of cells and axons.

二、The vertebrate nervous systems: a guide to the general organizational features of the nervous systems

Five principals of functional organization apply to all mammalian and most vertebrate brains

- Brain function is localized (stimulation studies, lesion studies, stroke and functional imaging studies)

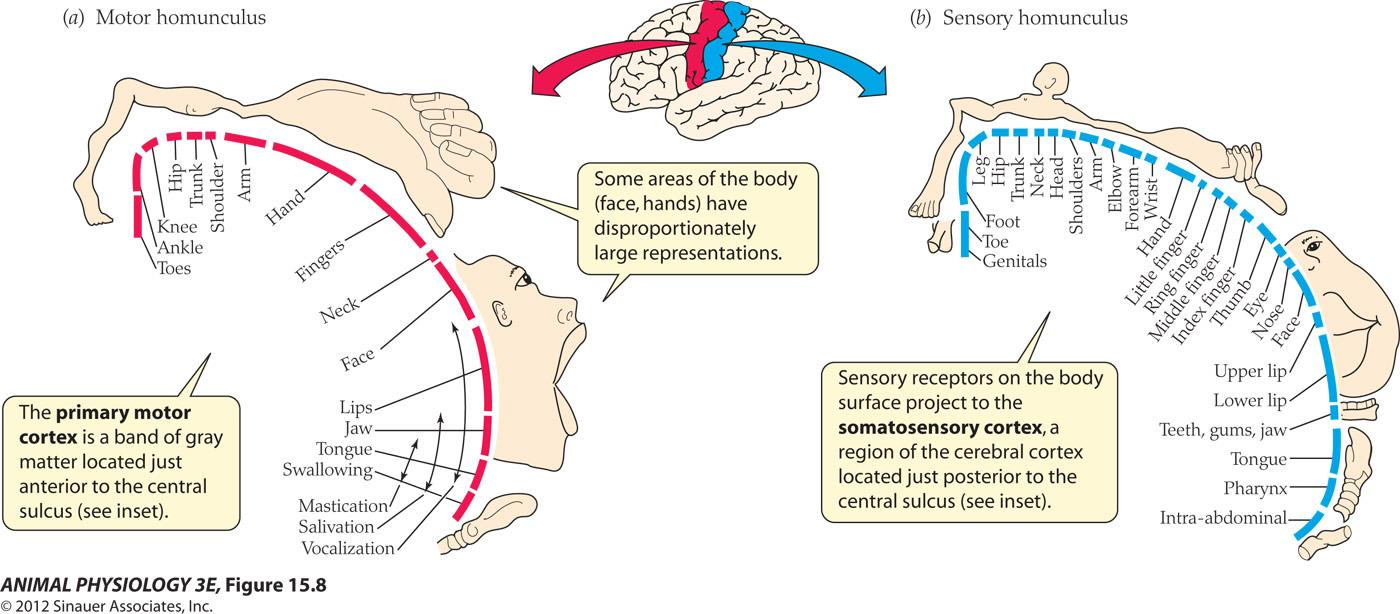

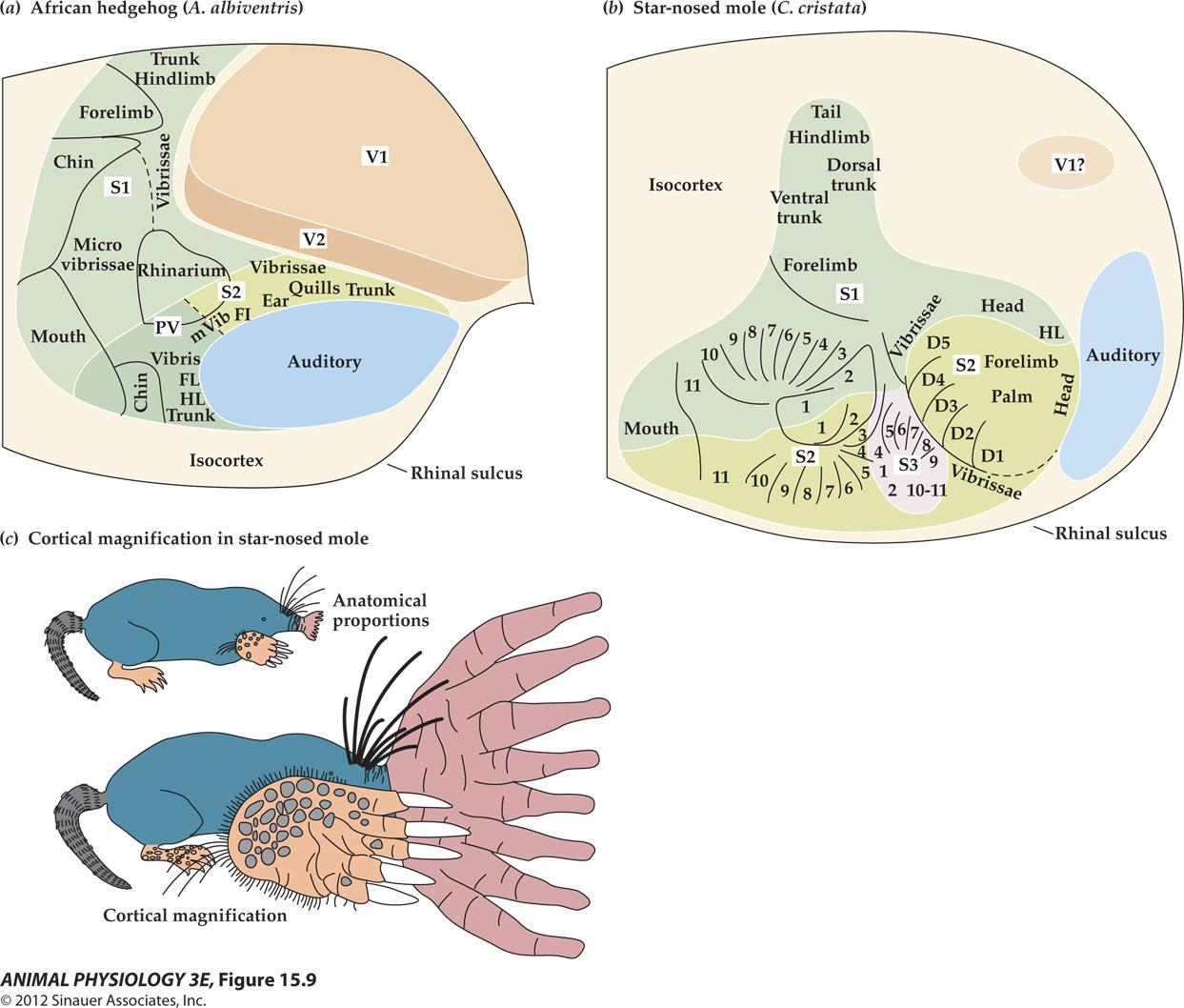

- Brains have maps (topographical representations of where a stimulus occurs. For example, sensory surface of the body is mapped onto the primary somatosensory area of the cerebral cortex).

- Size matters! The bigger the brain, the more neurons are present in it, and the more complex the integration that occurs

- Vertebrate brain evolution has involved repeated expansion of forebrain areas (the hind brains of fish and frog are similar to the corresponding areas of the mammalian brains, while birds and mammalian have evolved more complex forebrain structures.)

- Neural circuits are plastic (hard wired vs plastic synapses)

Some facts about the brain

The brain of Albert Einstein weighed 1,230 grams. This is far below the average brain weight of 1,400 grams

The brain of an elephant weighs about 4.78 kg (10.5 lb). An adult human brain weighs about 1.4 kg (3 lb)

The heaviest human brain ever recorded weighed 5 lbs., 1.1 oz (The Guinness Book of World Records, 1997).

The total surface area of the cerebral cortex is about 2500 sq. cm (~2.5 sq. ft).

It is estimated that there are 60 trillion synapses in the cerebral cortex.

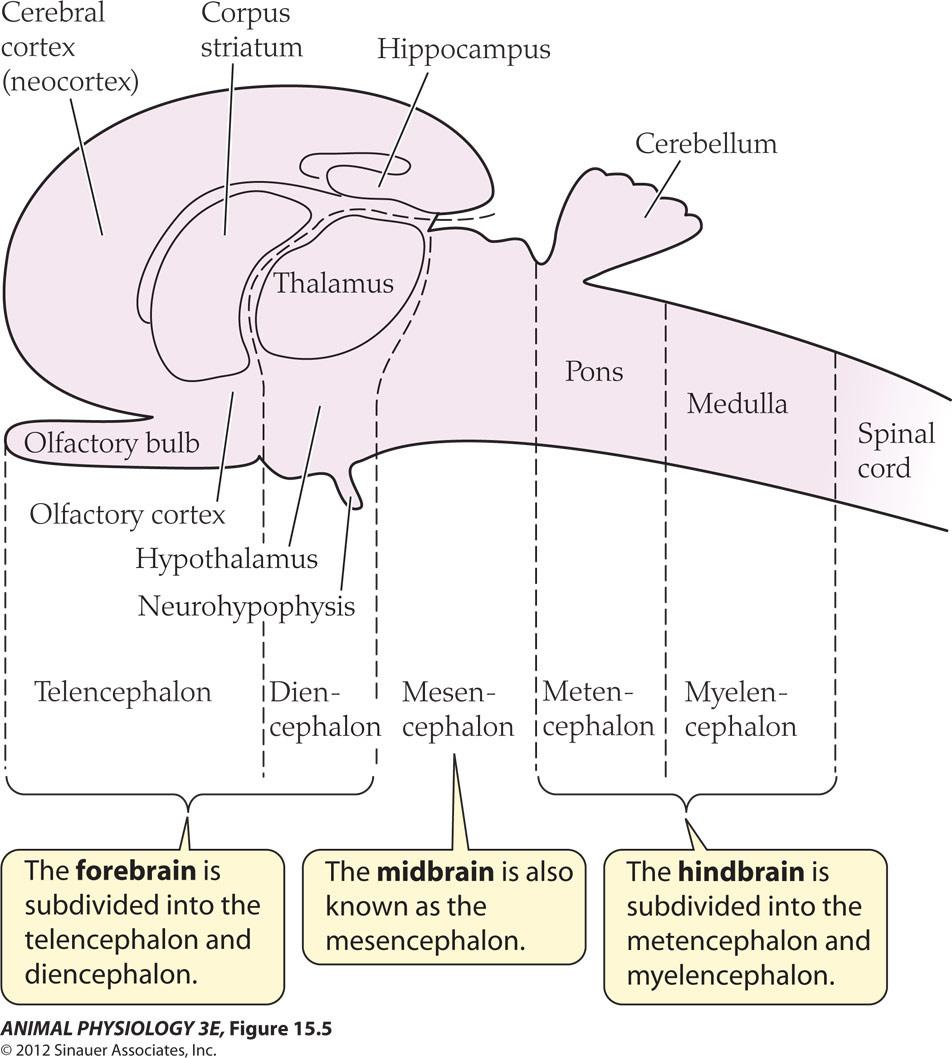

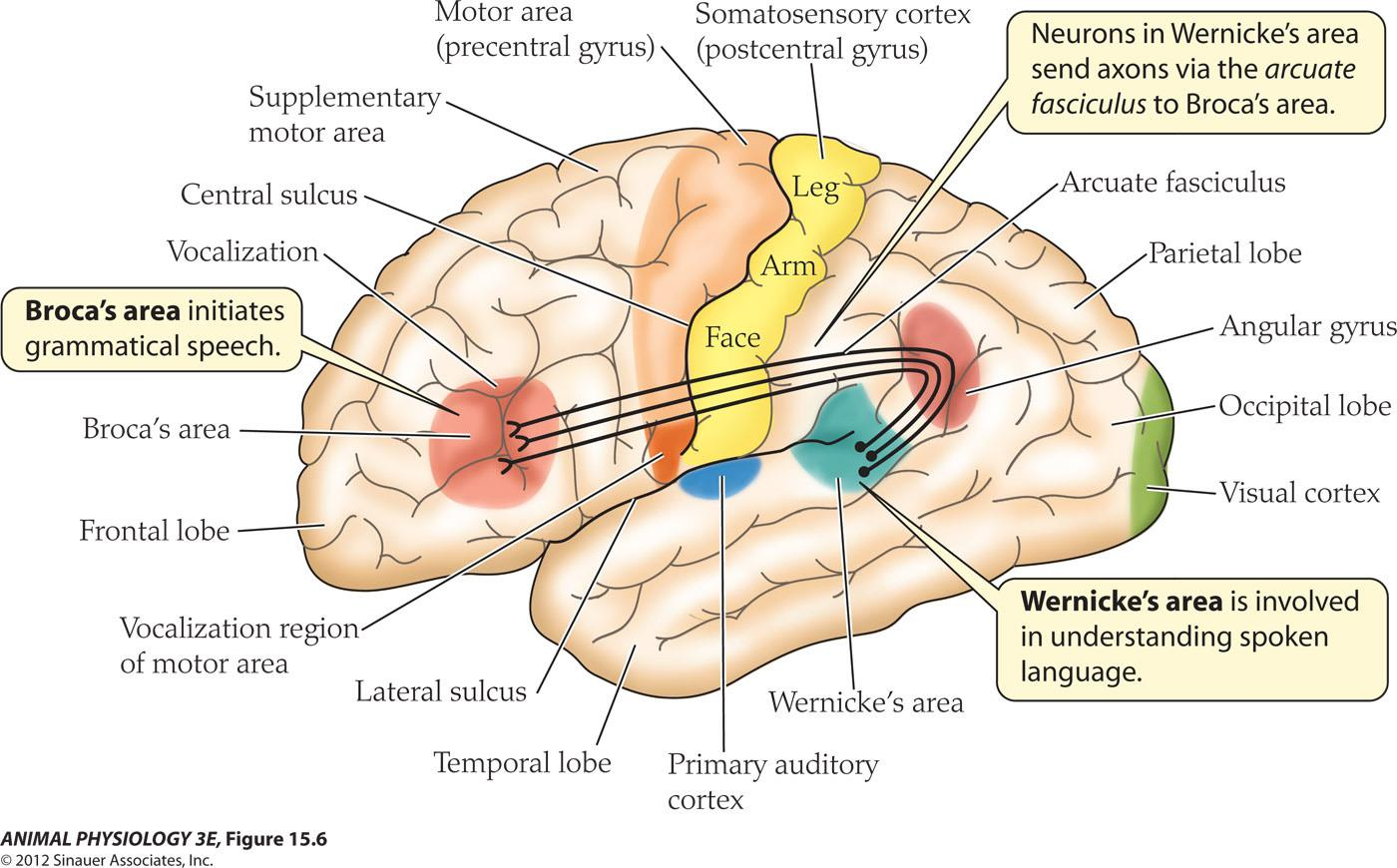

A schematic of vertebrate brain structure

- The forebrain is subdivided into the telencephalon(端脑) and diencephalon(间脑)

- The midbrain is also known as the mesencephalon.

- The hindbrain is subdivided into the metencephalon(后脑) and myelencephalon(髓脑)

All vertebrates share a common structural organization:

- Forebrain, midbrain and hindbrains

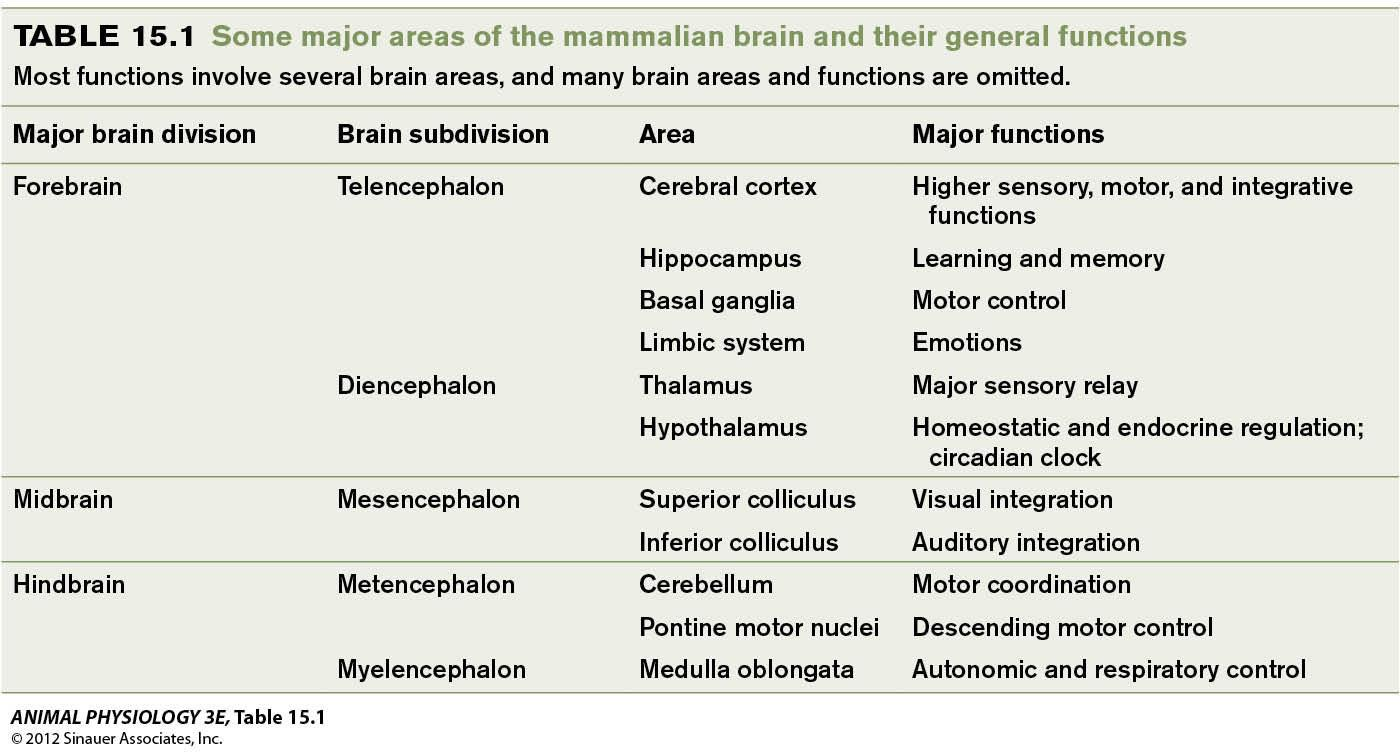

Four Lobes of the Brain

1. Parietal Lobe

Parietal Lobe is the area that is specialized for the body senses and body image

The parietal lobe is involved with processing information related to:

- Touch

- Pain

- Temperature

- Awareness of the location of body parts

Includes the Primary Somatosensory Cortex, a band of tissue on the front of the parietal lobe

- Each area of the primary somatosensory cortex receives information about touch in different body areas.

Larger areas are devoted to touch in the most sensitive parts of the body such as lips and hands.

Smaller areas are devoted to touch in less sensitive parts of the body such as the back and abdomen.

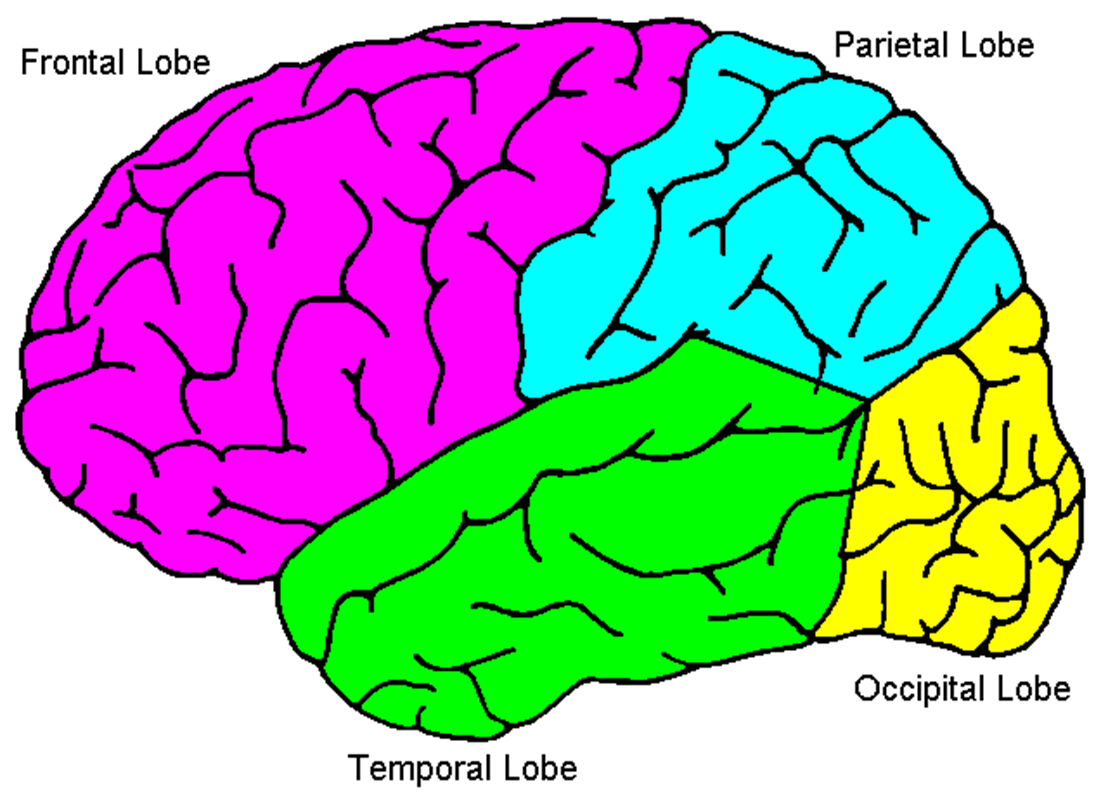

2. Localization of function in the human brain

- Broca’s area initiates grammatical speech.

- Wernicke’s area is involved in understanding spoken language.

- Neurons in Wernicke’s area send axons via the arcuate fasciculus to Broca’s area

Maps in the human brain

- The primary motor cortex is a band of gray matter located just anterior to the central sulcus(see inset).

- Some areas of the bod (face, hands)have disproportionately large representations.

- Sensory receptors on the bod surface project to the somatosensory cortex, a region of the cerebral cortex located just posterior to the central sulcus(see inset).

Somatotopic map: a map of the body projected to a brain area. Stimulation of a part of the motor cortex will elicit movement of the corresponding part of the body

However, maps of the brain are not universal and many areas of the mammalian brain lack topographical organization

3. Frontal Lobe

Includes the Primary Motor Cortex, which controls fine movements such as hand and finger movements

Each area of the primary motor cortex controls a different part of the body

- Larger areas are devoted to precise movements of the tongue and fingers

- Smaller areas are devoted to movements of the shoulders and elbows

Wiggle your fingers as fast as you can. Now wiggle your toes…see the difference? This is because you have more motor cortex devoted to your fingers than you do in your toes!

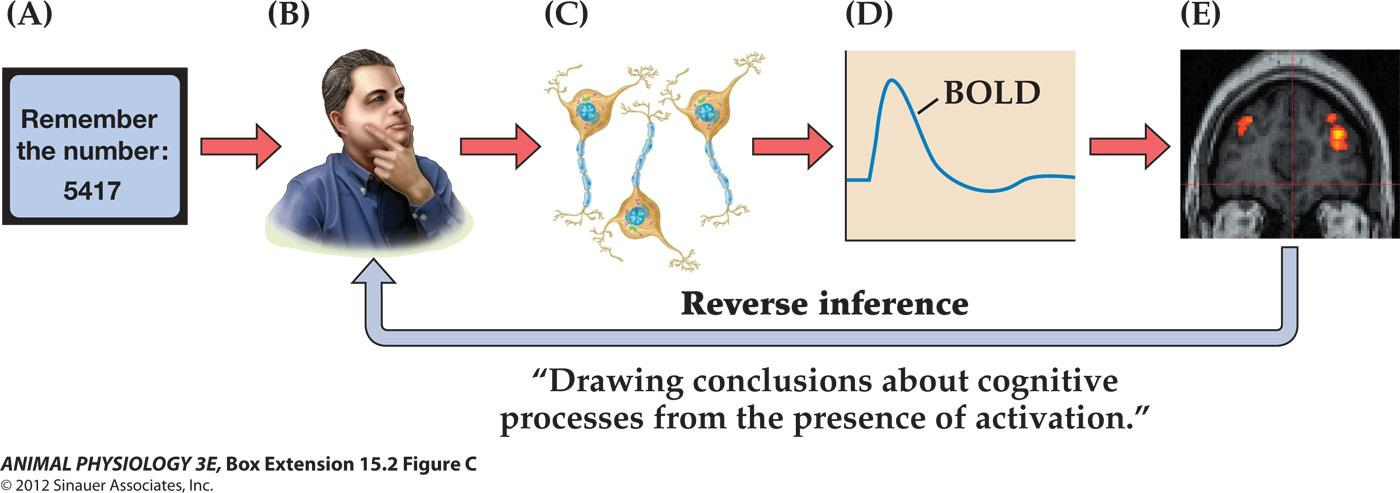

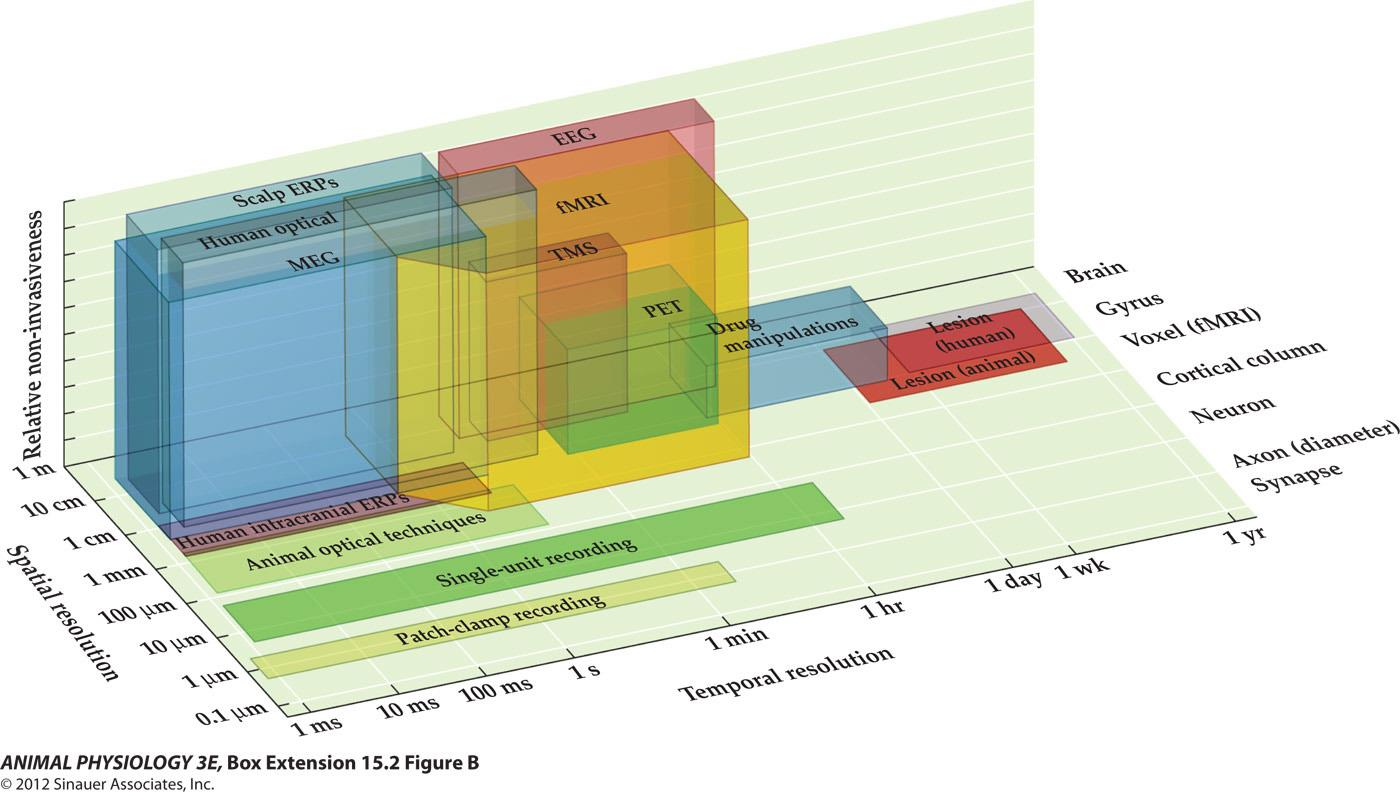

Functional neuroimaging demonstrates localization of function in the human cerebral cortex

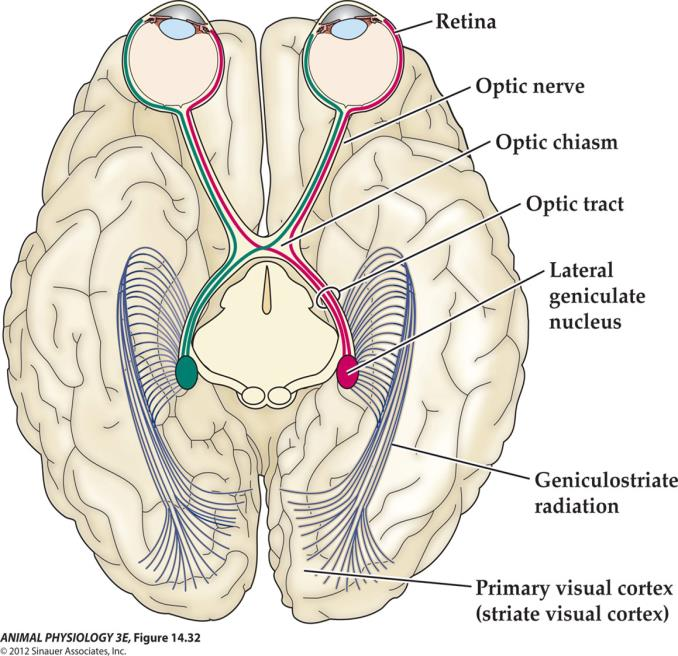

FIGURE 15.7 Functional neuroimaging demonstrates localization of function in the human cerebral cortex Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows increased activity of particular brain areas. This fMRI sectional image of a brain (seen from above; left is anterior) shows increased neural activity during a visual stimulus. The neural activity (measured as increased flow of oxygenated blood and shown in red) increases in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus (middle) and the primary visual cortex (posterior). (See Figure 14.32 for a diagrammatic view of this pathway and Box 15.2 for a discussion of fMRI as an imaging method.) (From Chen et al. 1999.)

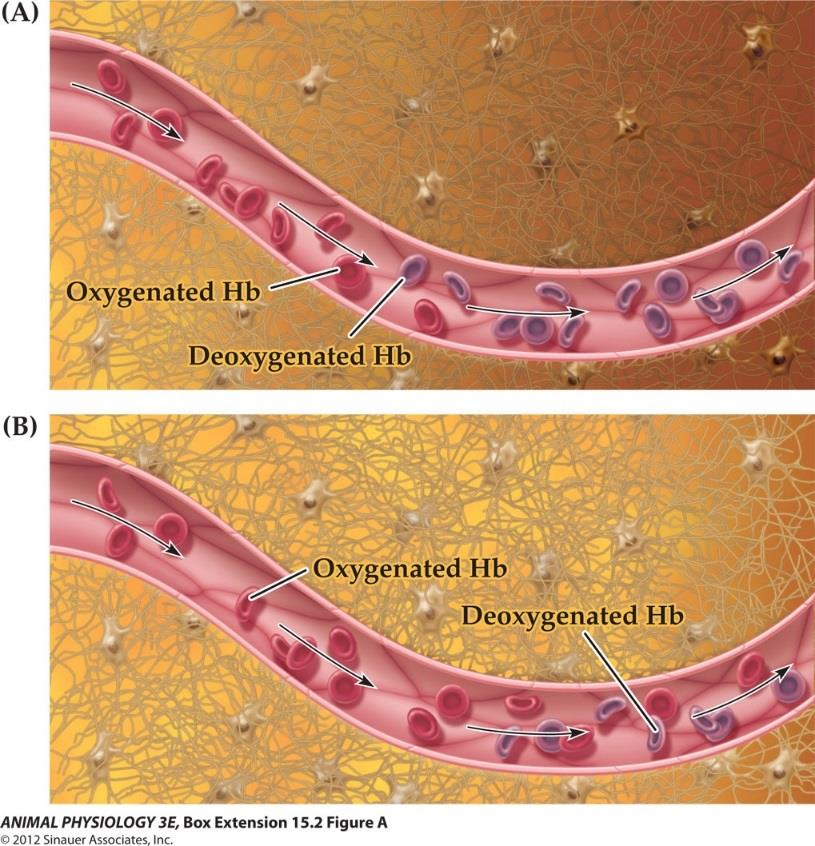

The primary form of fMRI uses the blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) contrast, discovered by Seiji Ogawa. This is a type of specialized brain and body scan used to map neural activity in the brain or spinal cord of humans or other animals by imaging the change in blood flow (hemodynamic response) related to energy use by brain cells.

Summary of BOLD signal generation

- fMRI research involves making a chain of inferences

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging:

- Blood-oxygen-level dependent contrast imaging, or BOLD-contrast imaging

Maps in the brain differ for different animal groups

- Greatly reduced visual area(V1?)

- Posteriorly displaced auditory area

- Three large areas (numbered 1-11) represent the star nose (vs S2 and PV)

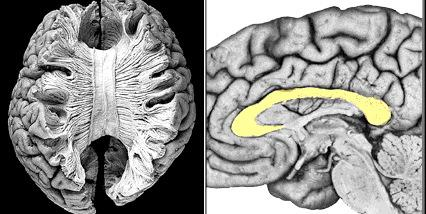

4. The Organization of the Nervous System

CNS: Brain and Spinal cord

PNS: The peripheral nervous system has somatic and autonomic divisions that control different parts of the body

- somatic nervous system;

- autonomic nervous system

The Nervous System

Central Nervous System (CNS):

- The brain

- The spinal cord

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

- The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the limbs and organs

CNS-Spinal Cord:

- The spinal cord transmits signals from the sensory organs, muscles and glands to the brain

- Controls reflexive responses

- Conveys signals from the rest of the body

- The spinal cord is like a communication superhighway between the brain and the rest of the body.

Spinal cord communication

Communicates with the body below the head through sensory and motor neurons

Sensory neurons (afferent neurons)

- Carry information about touch, pain, and other senses from the periphery of the body to the spinal cord

Motor neurons (efferent neurons)

- Transmit impulses from the central nervous system to the muscles and glands

5. Structures of the brain

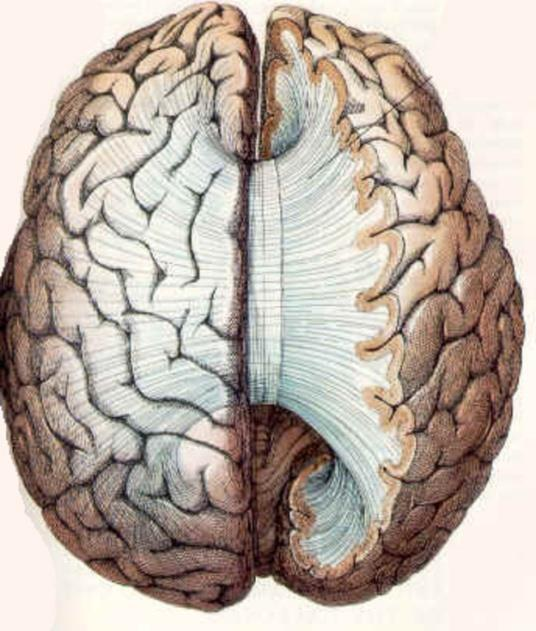

Looking at the Brain:

- The exterior covering (cortex) of the brain is wrinkled which increases the surface area of the brain

- The brain is divided into 2 hemispheres

The hemispheres of the brain are connected

- The Corpus Callosum(胼胝体) connects these hemispheres and allows communication from one side of the brain to the other

(1) Hemispheric Specialization

Damage to the Corpus Callosum results in two independent brains in one skull

Split brain patients allowed researchers to discover “hemispheric specialization”

Left Brain

- Controls Right Side of Body

- Right Side Visual Field

- Speaking

- Reading

- Logical Thinking

- Analytical Skills

- Sequential Processing 顺序处理

Right Brain

- Controls Left Side of Body

- Left Side Visual Field

- Spatial Processing 空间处理

- Facial Recognition 面部识别

- Music

- Emotional Expression

- Holistic Thinking 整体思维

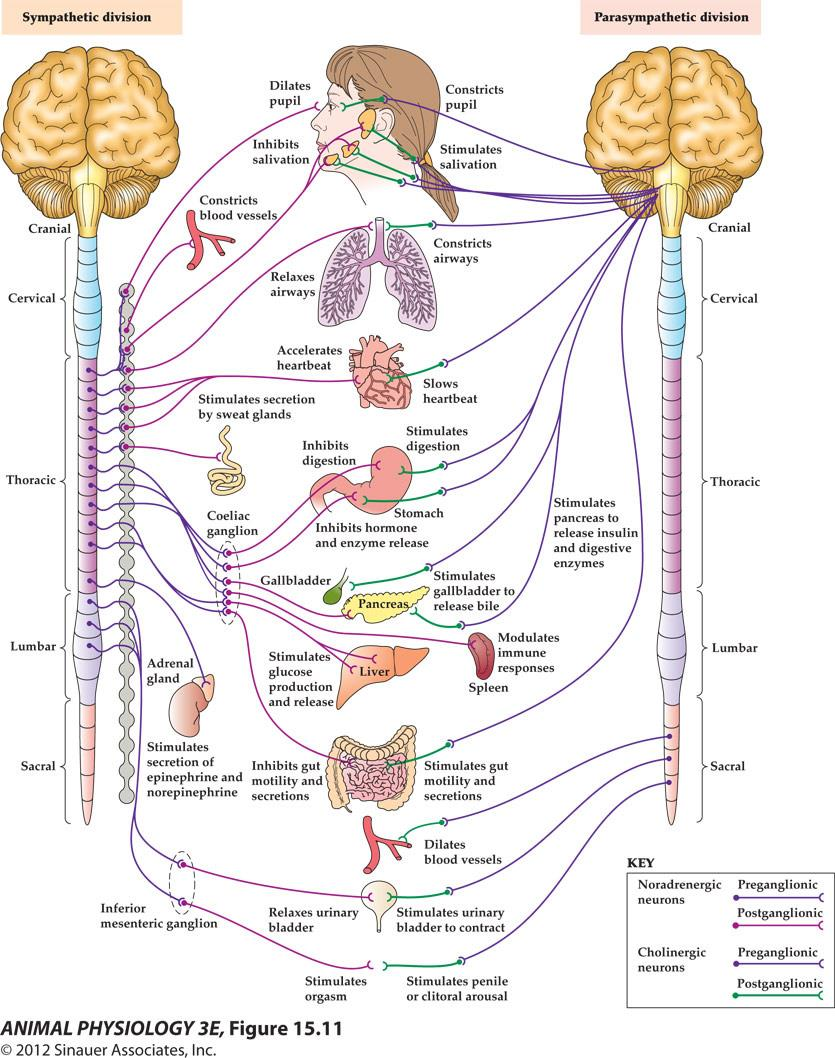

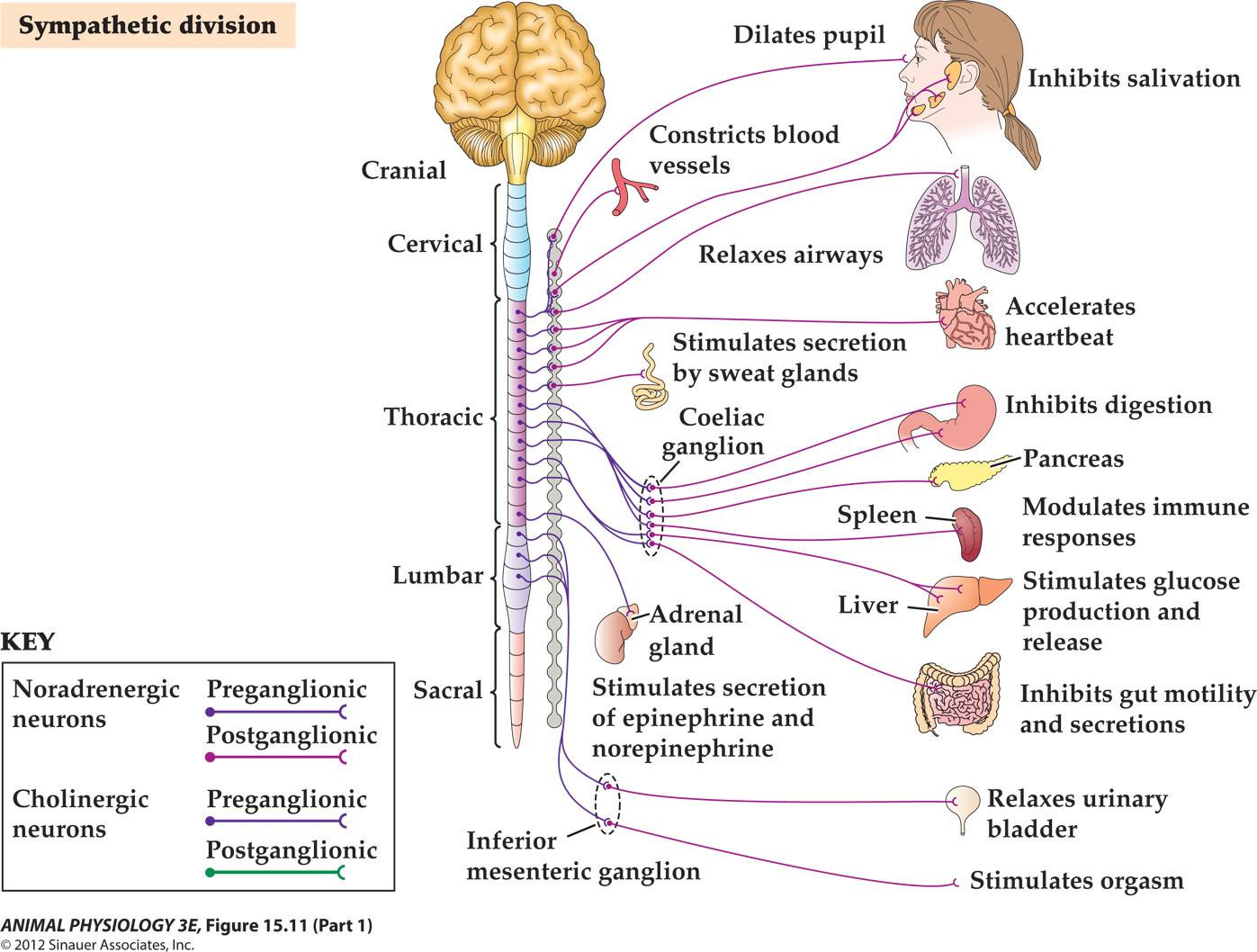

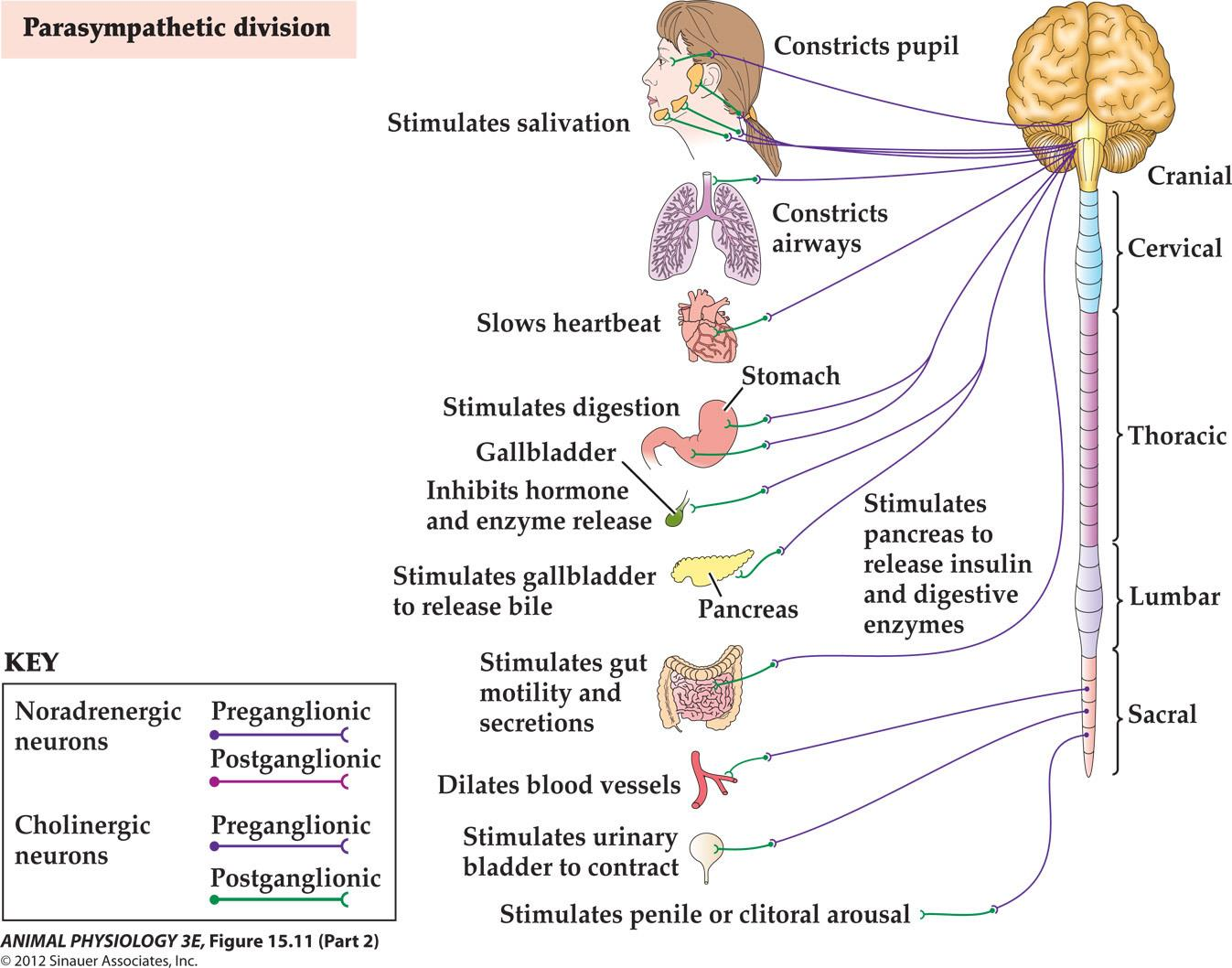

Divisions of the vertebrate nervous system are interconnected

The vertebrate autonomic nervous system have three divisions: (sympathetic and parasympathetic have opposite effects)

- Sympathetic nerves(交感神经) (fight-or-flight response)

- Parasympathetic nerves(副交感神经) (rest-and-digest functions)

- Enteric neurons(肠神经元) (mostly anatomical, and contained in the walls of the gut)

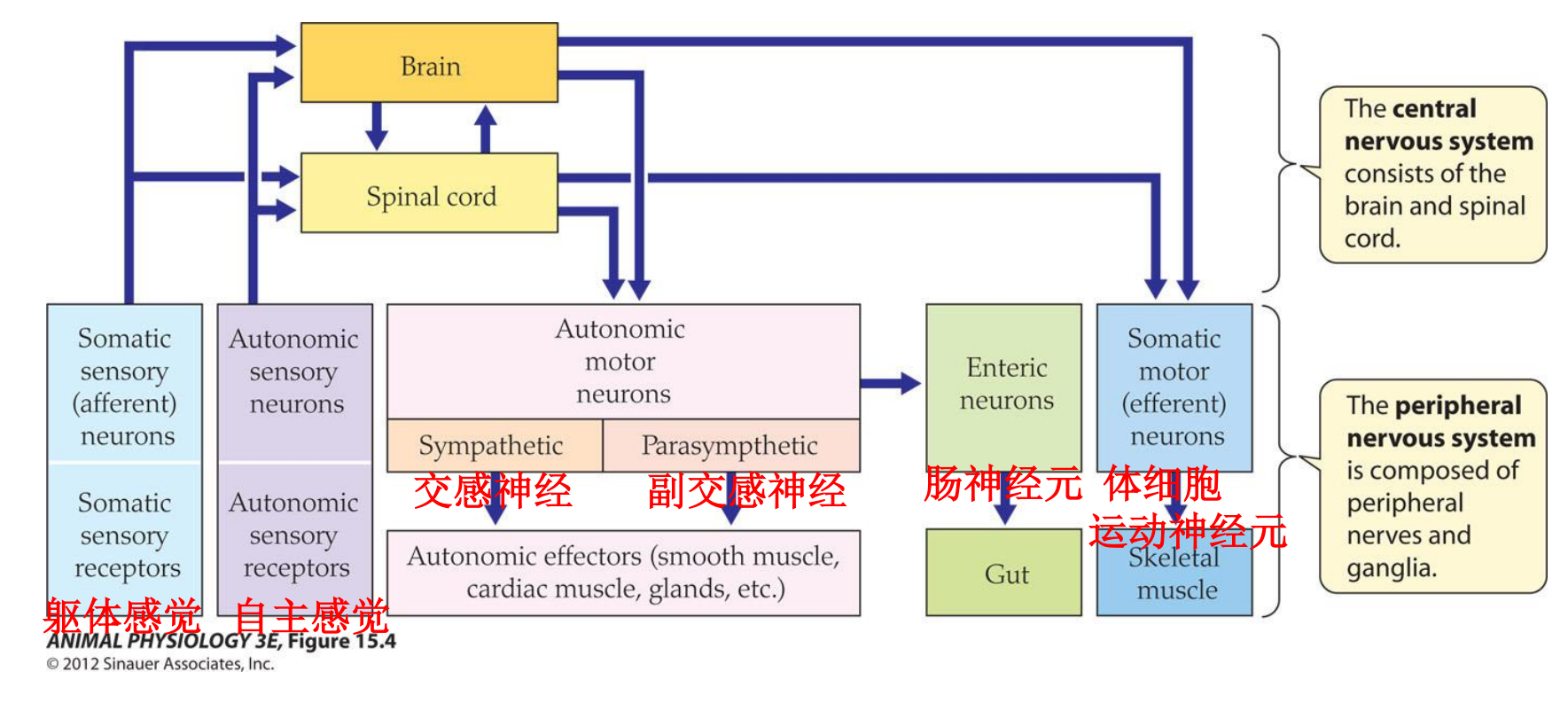

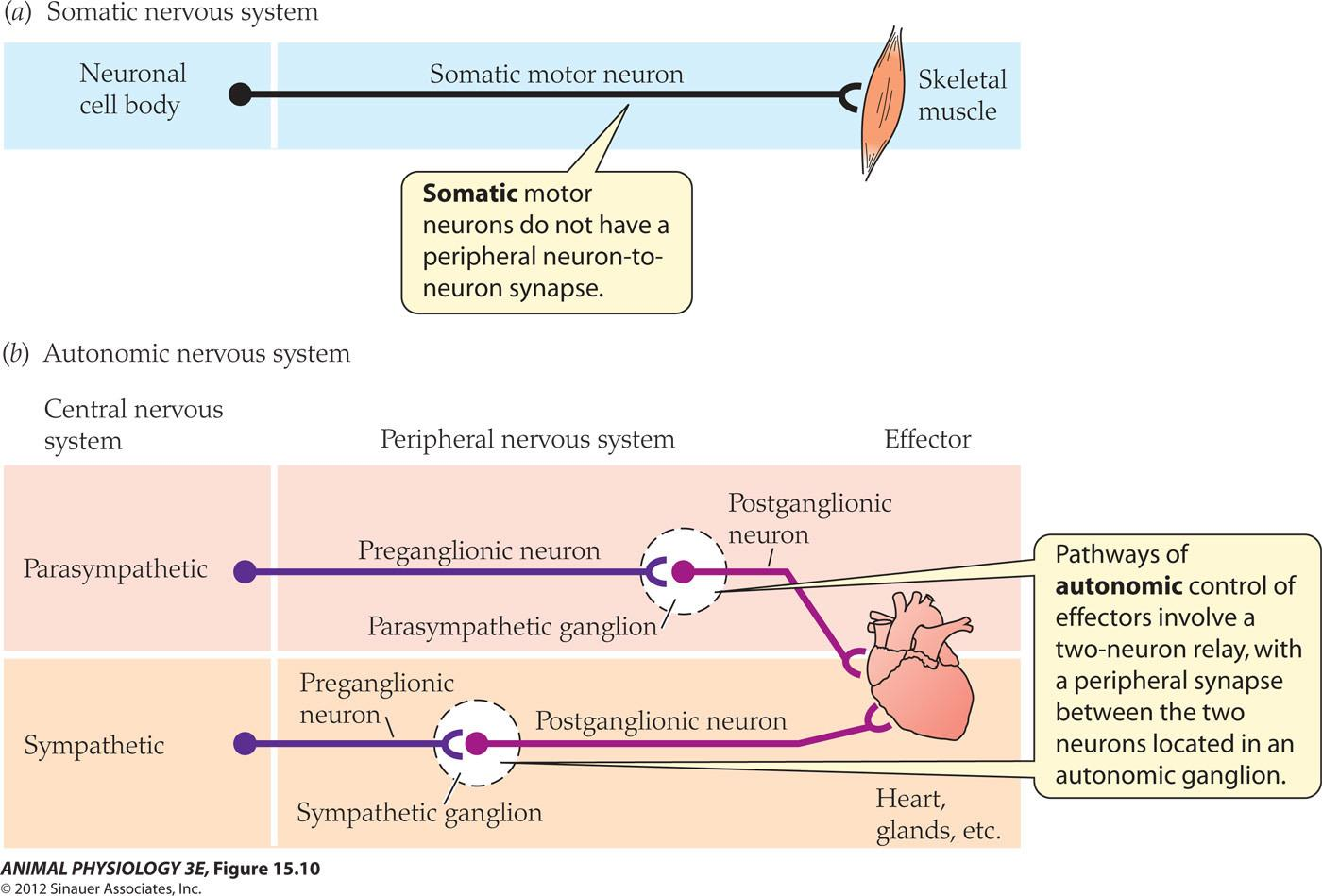

The organization of the mammalian somatic and autonomic nervous systems, including examples of effector organs

- Somatic motor neurons do not have a peripheral neuron-to-neuron synapse.

- Pathways of autonomic control of effectors involve a two-neuron relay, with a peripheral synapse between the two neurons located in an autonomic ganglion

- The location of the ganglion is different between sympathetic and parasympathetic: parasympathetic division is located close to the effector.

- Parasympathetic division Exit the CNS from cranial and sacral

Parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system provide dual innervation of most visceral autonomic effectors

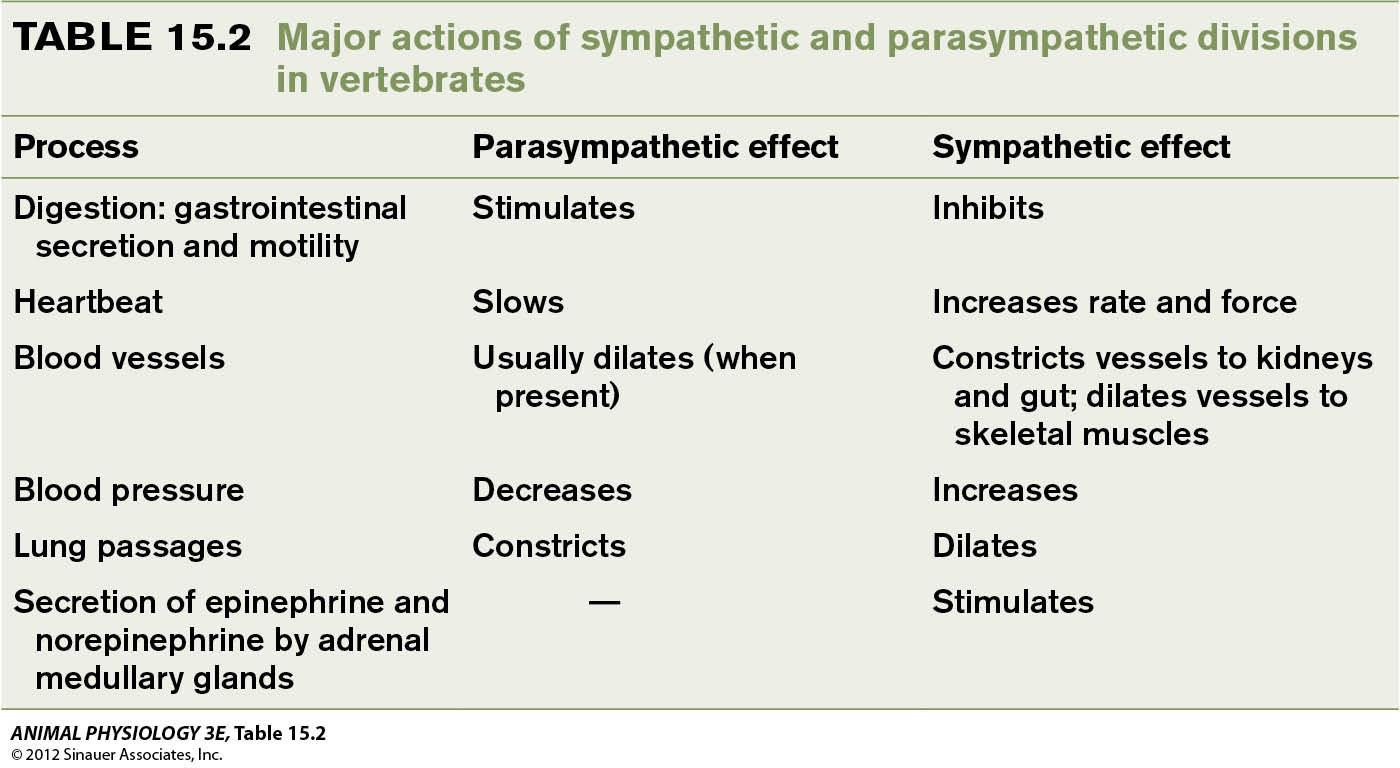

FUNCTION OF THE SYMPATHETIC AND PARASYMPATHETIC DIVISIONS

- The postganglionic neurons of the parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions release different chemical neurotransmitter substances at their synapses with effector cells.

- Parasympathetic postganglionic neurons typically release acetylcholine 乙酰胆碱 and thus are termed cholinergic.

- Sympathetic postganglionic neurons release mainly catecholamines 儿茶酚胺—chiefly norepinephrine (noradrenaline) in mammals— and thus are called adrenergic (or noradrenergic).

Functions of the parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions:

Sympathetic division:

- Inhibits salivation

- Accelerates heartbeat

- Inhibits digestion

- Control pancreas

- Modulates immune responses

- Stimulates glucose production and release

- Inhibits gut motility and secretions

- Relaxes urinary bladder

- Stimulates orgasm

Parasympathetic division:

- Stimulates salivation

- Slows heartbeat

- Stimulates digestion in stomach

- Inhibit hormone and enzyme release in gallbladder

- Stimulates gallbladder to release bile

- Stimulates gut motility and secretions

- Dilates blood vessels

- Stimulates urinary bladder to contract

- Stimulates penile or clitoral arousal

The autonomic effectors that are controlled at least partly by the vertebrate autonomic nervous system include:

- Smooth muscles throughout the body: in the gut wall, blood vessels, eyes, urinary bladder, hair follicles, spleen, airways of the lungs and penis.

- Many exocrine glands (sweat glands, tear glands and the exocrine portion of the pancreas) [exocrine glands discharge into the internal body cavity or environment, while endocrine glands secrete into the blood or other body fluids]

- Acid-secreting cells of the stomach

- The pacemaker region and other parts of the heart

- The brown adipose tissue of mammals

Parasympathetic postganglionic neurons typically release Ach (cholinergic) rest-and-digest functions

Sympathetic postganglionic neurons release catacholamines (norepinepherine) are called andrenergic. Fight-or-flight response

The enteric nervous system controls the GUT an elaborate network of neurons located entirely within the walls of the gut. More than 200-600 million neurons in humans

(1) Fight-or-flight response

Definition: This is the body’s response to perceived threat or danger.

- During this reaction, certain hormones like adrenalin and cortisol are released, speeding the heart rate, slowing digestion, shunting blood flow to major muscle groups, and changing various other autonomic nervous functions, giving the body a burst of energy and strength.

- Originally named for its ability to enable us to physically fight or run away when faced with danger, it’s now activated in situations where neither response is appropriate, like in traffic or during a stressful day at work. When the perceived threat is gone, systems are designed to return to normal function via the relaxation response, but in our times of chronic stress, this often doesn’t happen enough, causing damage to the body.

(2) Rest-and-digest response

Definition: The counterpart to the fight-or-flight response, the relaxation response occurs when the body is no longer in perceived danger, and the autonomic nervous system functioning returns to normal.

- During this response, the body moves from a state of physiological arousal, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, slowed digestive functioning, decreased blood flow to the extremities, increased release of hormones like adrenalin and cortisol, and other responses preparing the body to fight or run, to a state of physiological relaxation, where blood pressure, heart rate, digestive functioning and hormonal levels return to their normal state. During acute stress, this response occurs naturally.

- However, in times of chronic stress, when the body is in a constant state of physiological arousal over perceived threats that are numerous and not life-threatening, the relaxation response can be induced through techniques such as meditation, yoga, tai chi, deep breathing exercises, self-hypnosis and other tension taming and stress-management techniques.

Summary

SUMMARY The Vertebrate Nervous System: A Guide to the General Organizational Features of Nervous Systems

The CNS of vertebrates consists of the brain and spinal cord. Cranial and spinal nerves emanate from the CNS to form the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The brain is divided into a forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain; the forebrain is enlarged in birds and especially in mammals

Vertebrate brain functions are somewhat localized. However, brain functions are also somewhat distributed, involving circuits rather than centers.

Many vertebrate brain regions preserve the orderly spatial arrangements of the corresponding external world, for example, as somatotopic maps of body sensory input and motor output.

三、Biological clocks

Biological clocks – endogenous rhythms

- Animals that use endogenous physical timing mechanism to rhythmically modulate the function of cells, tissues and organs, called biological clock.

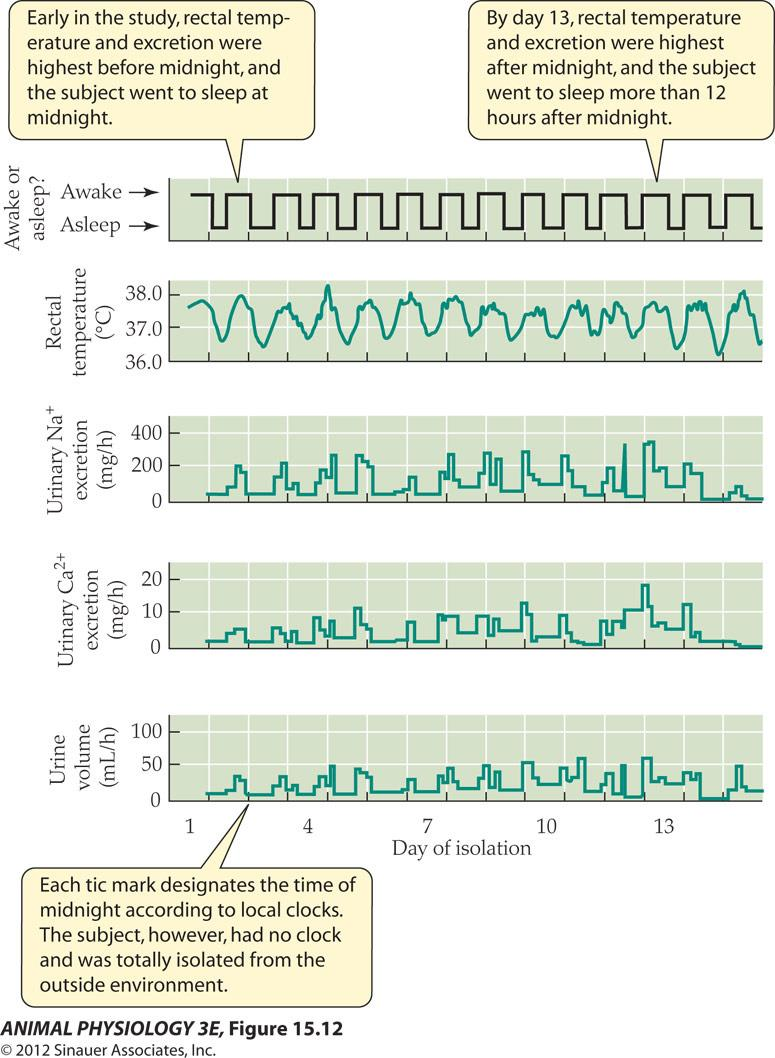

Daily rhythm of several physiological functions in a human

- Early in the study, rectal temperature and excretion were highest before midnight, and the subject went to sleep at midnight.

- By day 13, rectal temperature and excretion were highest after midnight, and the subject went to sleep more than 12 hours after midnight

- Each tic mark designates the time of midnight according to local clocks The subject, however, had no clock and was totally isolated from the outside environment

FIGURE 15.12 Daily rhythm of several physiological functions in a human

- A young man lived by himself in an apartment without clocks, telephones, windows, or other avenues whereby he could know the time of day in the outside world. He could turn the lights on and off, prepare food, go to bed, urinate, and engage in other processes of daily living, but his timing of those activities was based entirely on his endogenous, physiological sense of time. This graph shows his patterns of variation in five remotely monitored functions during his first 15 days of life without knowledge of external time. (After Wever 1979.)

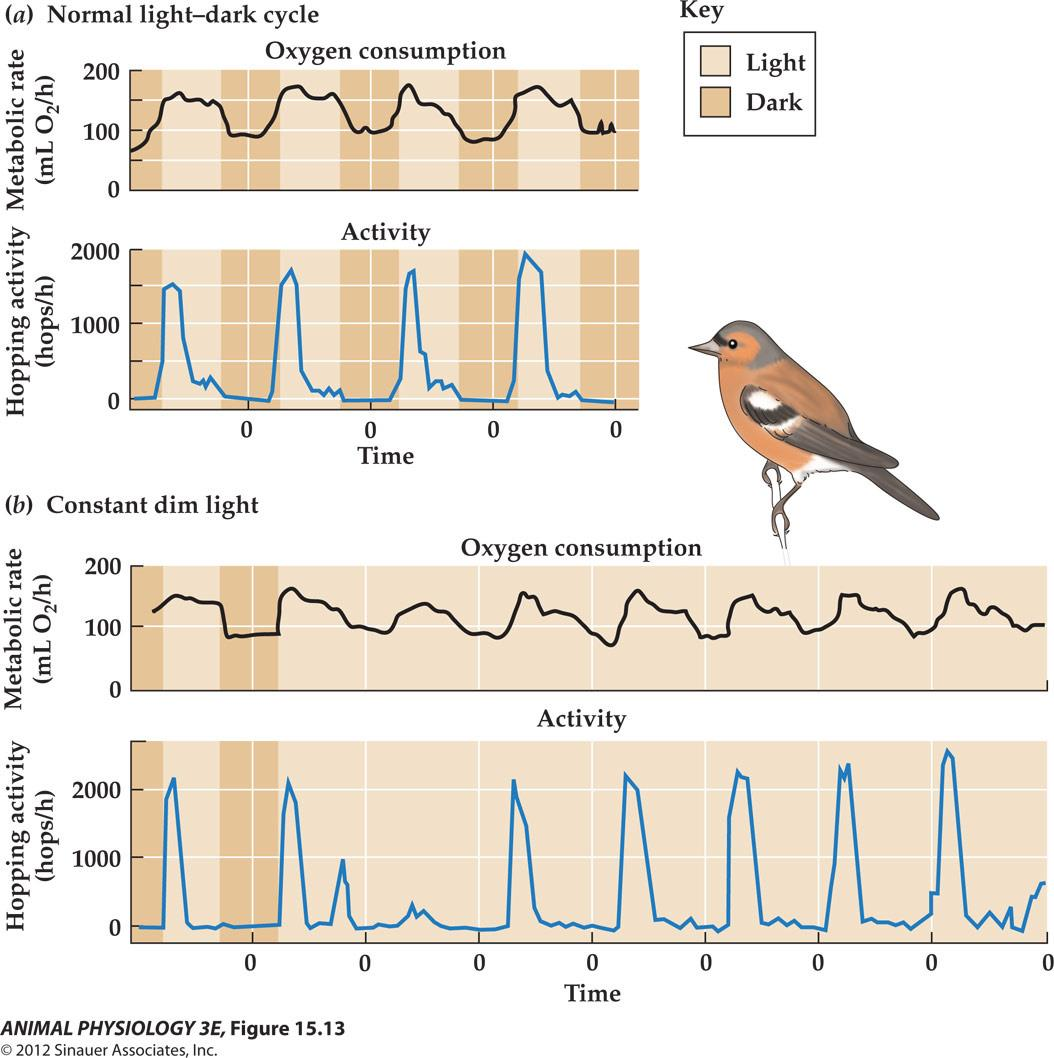

Circadian rhythm of metabolic rate (O2 consumption) and motor activity for a chaffinch

Sleep

Why do animals sleep?

- Humans spend one-third of our entire lives sleeping!

- Endogenous rhythms has a period of about a day is called Circadian rhythm

- Controlled by clock genes

Why animals sleep continues to be one of the most elusive and mysterious questions in biology. Sleep, nonetheless, is found widely among animals—from relatively simple phyla such as worms (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans) to higher-order groups such as humans—suggesting that sleep is a required, evolutionarily conserved behavior.

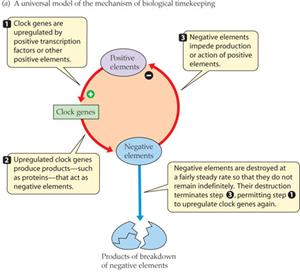

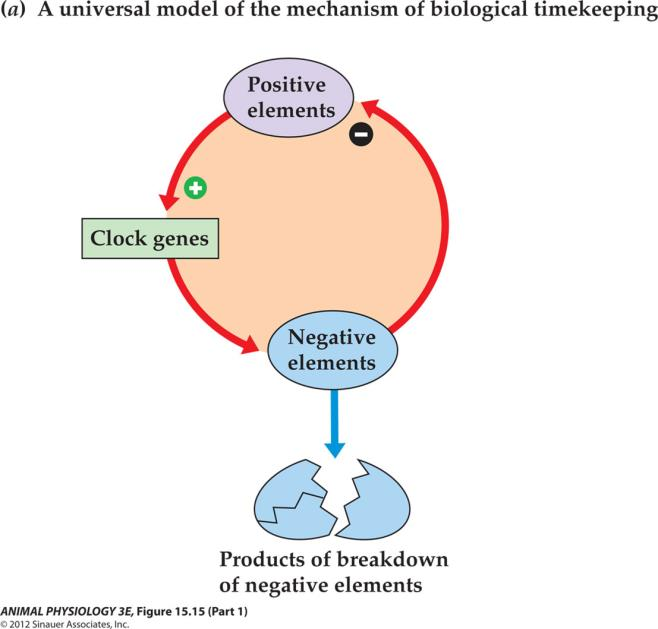

1. Cellular mechanisms of circadian time-keeping

- clock genes are upregulated by positive transcription factors or other positive elements

- Upregulated clock genes produce products, such as proteins, that act as negative elements

- Negative elements impede production of action of positive elements

- Negative elements are destroyed at a fairly steady rate so that they do not remain. Their destruction terminates step 3, permitting step 1 to upregulate clock gene again.

Clock mechanisms are based on rhythms of gene expression

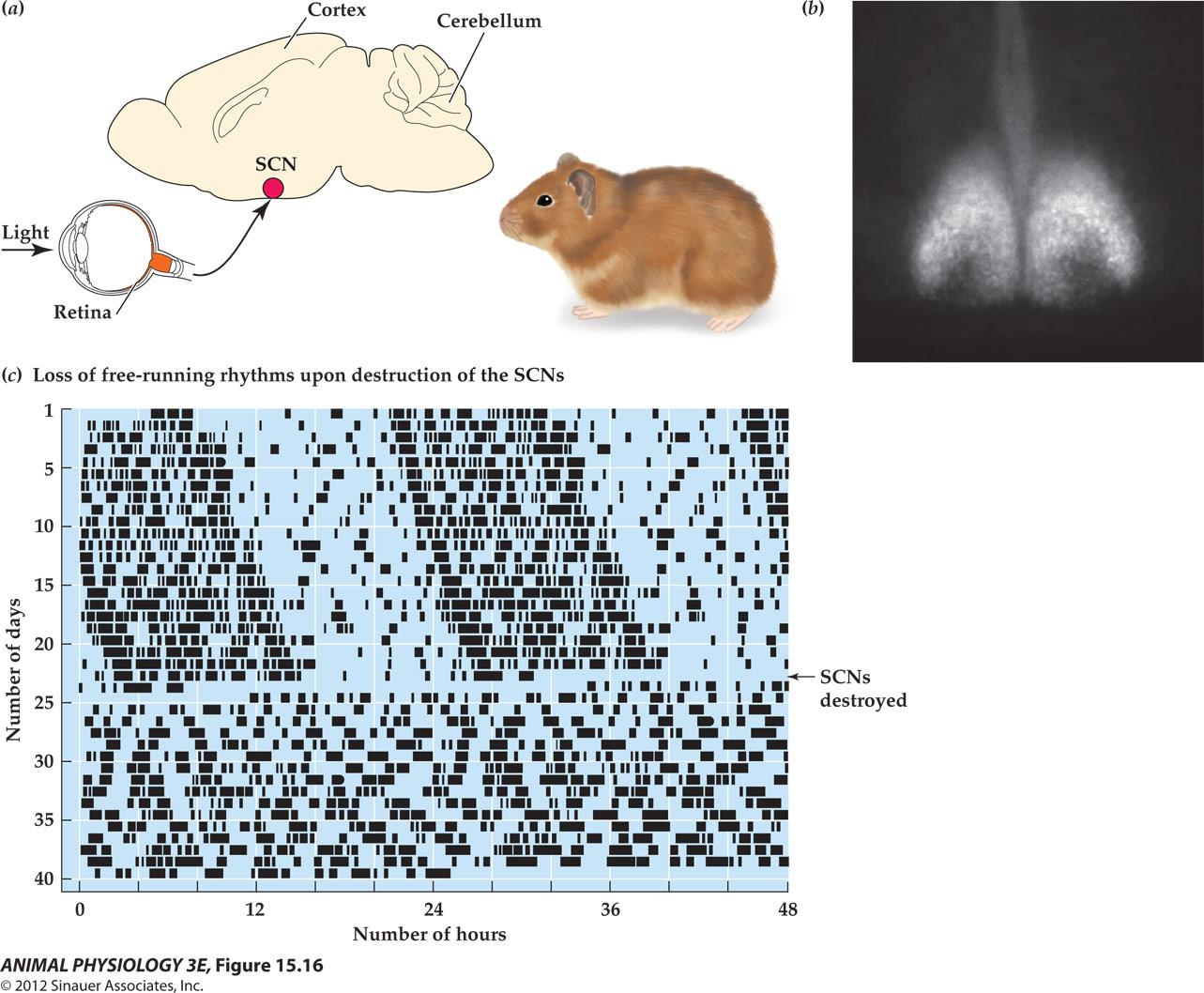

The paired suprachiasmatic nuclei in the brain constitute the major circadian clock of mammals

- suprachiasmatic nuclei 视交叉上核

Summary

A circadian rhythm has a period of about a day. It is an example of an endogenous rhythm, one that does not require sensory information for timing

A circadian rhythm of an animal will drift, or free-run, in constant light or darkness, when there are no sensory timing cues. A light–dark cycle entrains the circadian rhythm to exactly 24 h

A biological clock is the physiological basis of an animal’s ability to time an endogenous rhythm. Biological clocks exert rhythmically changing control, modulating the outputs of the nervous and endocrine systems to prepare an animal for daily changes and seasonal changes. In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the brain is the principal biological clock for circadian rhythms.

Animals may possess other timing mechanisms for shorter rhythmic periods (such as circatidal rhythms) or longer periods (such as circannual rhythms) than those of circadian rhythms.