L13 Enzyme inhibition

一、Enzyme Inhibition

Why we needs enzyme inhibition:

One reaction cannot be constantly precessed.

Inhibition of enzymes can be either reversible inhibitors and irreversible inhibitors.

Reversible Inhibition

Reversible inhibition involves noncovalent binding of the inhibitor and can always be reversed, at least in principle, by removal of the inhibitor.

They differ in the mechanisms by which they decrease the enzyme’s activity and in how they affect the kinetics of the reaction.

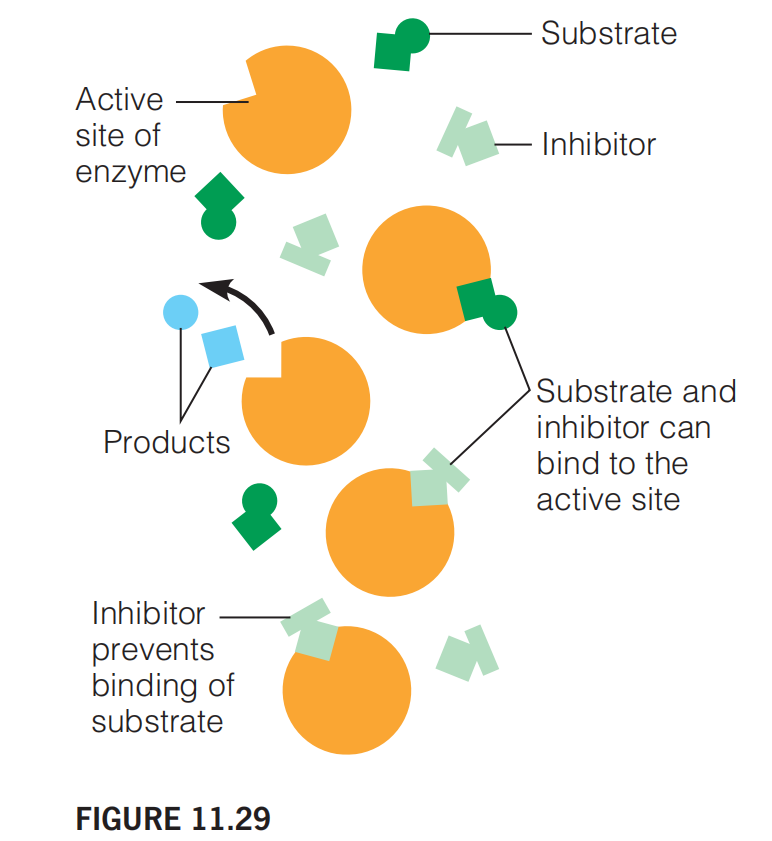

1. Competitive Inhibition

Introduction

A competitive inhibitor competes with substrate for the enzyme active site. It increases the $K_{M}$

It competes with the substrate for binding to the same site on the enzyme.

Both substrate and inhibitor can fit the active site. Substrate can be processed by the enzyme, but inhibitor cannot.

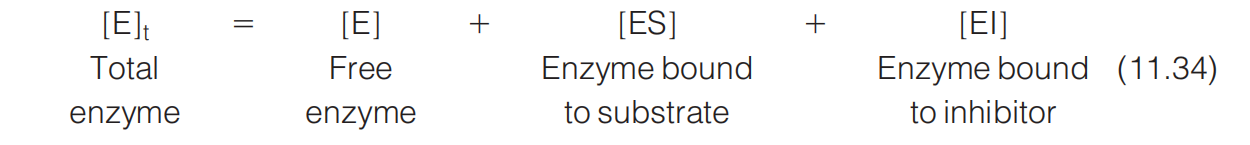

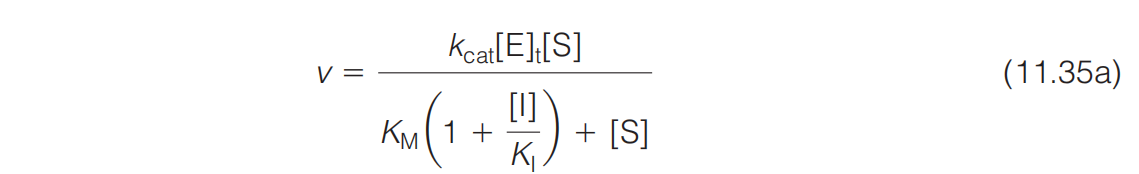

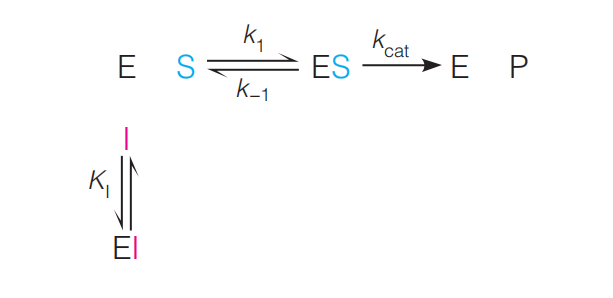

Upon analysis of this case, the expression for v is found to be equation 11.35a

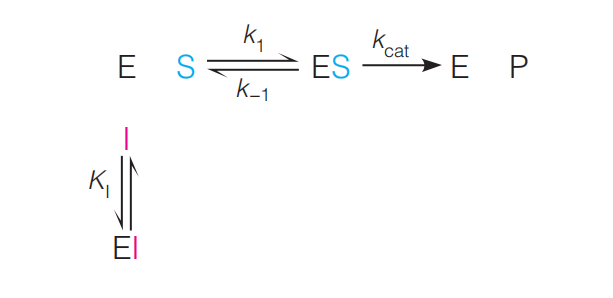

v equation Deduction

Define: $[I]$ is the concentration of inhibitor and $K_{I}$

$$

K_{I} = [E] [I] / [EI]

$$

$$

\because [E]{t} = [E] + [ES] + [EI] \ K{M} = \frac{[E] [S]}{[ES]} \ K_{I} = \frac{[E] [I]}{[EI]}

$$

$$

\therefore [E]{t} = [E] + [ES] + \frac{[E] [I]}{K{I}}

$$

$$

\therefore [E]{t} - [ES] = [E] (1 + \frac{[I]}{K{I}})

$$

$$

\because K_{M} [ES] = [E][S] = \frac{[E]{t} - [ES]}{1 + \frac{[I]}{K{I}}} \cdot [S]

$$

$$

\therefore K_{M} [ES] (1 + \frac{[I]}{K_{I}}) = [E]_{t} [S] - [ES] [S]

$$

$$

\therefore v = k_{cat} [ES] = \frac{k_{cat} [E]{t} [S]} {(1 + \frac{[I]}{K{I}}) K_{M} + [S]} = \frac{V_{max} [S]}{\alpha K_{M} + [S]} = \frac{V_{max} [S]}{K_{M}^{app} + [S]}

$$

Then we get equation 11.36

$$

K_{M}^{app} = \alpha K_{M} = (1 + \frac{[I]}{K_{I}}) K_{M} = K_{M} + \frac{K_{M}}{K_{I}} [I]

$$

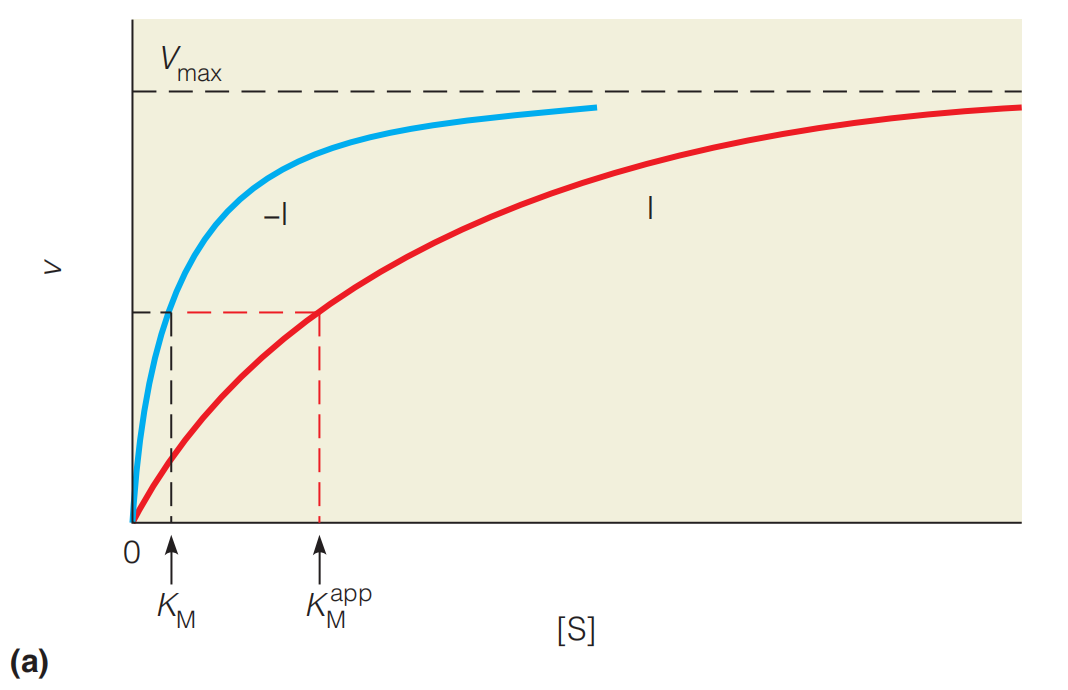

Effects of competitive inhibition on enzyme kinetics

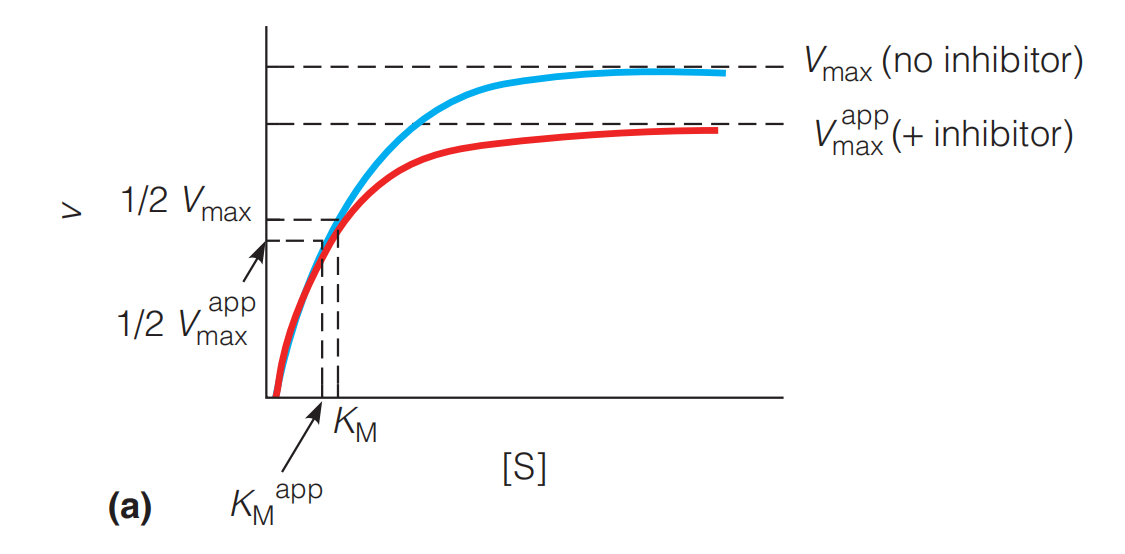

(a) The effect of a competitive inhibitor (I) on reaction velocity at different substrate concentrations. Two sets of substrate-velocity experiments were carried out, one with (red line) and one without (blue line) inhibitor present.

Addition of the inhibitor decreases the velocity but not the $V_{max}$. For competitive inhibition the maximum velocity is unchanged because as [S] becomes very large, v approaches $V_{max}$ (just as in the absence of inhibition),

and $V_{max} = k_{cat} [E]_{t}$

The apparent $K_{M} $ is higher in the presence of inhibitor.

As predicted, increasing [I] causes an increase $K_{M}$ in the apparent

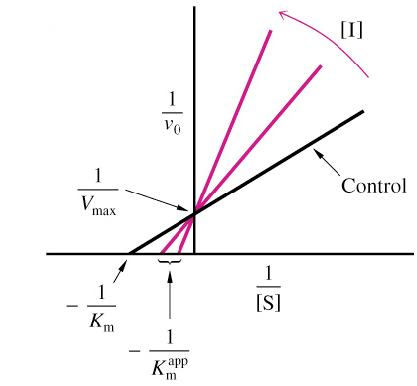

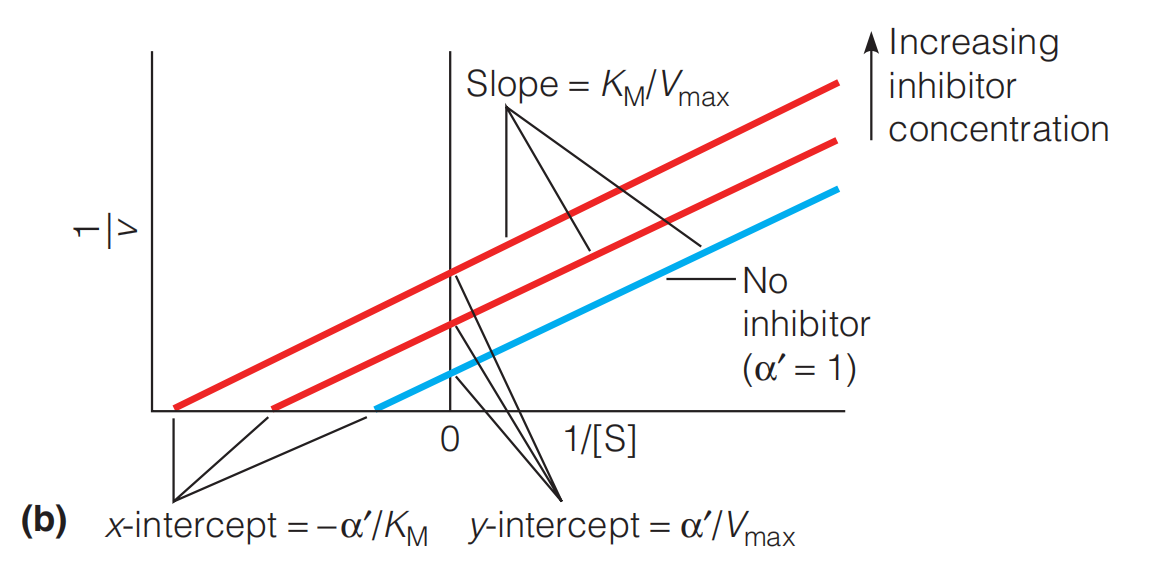

(b) Figure(b) is the Lineweaver–Burk plots of the reactions shown in (a).

The lines cross the 1/v axis at the same $V_{max}$, showing that I is a competitive inhibitor.

(c) Determination of KM and KI . If the measurement of is repeated at different concentrations of I, KI can be determined from the slope of the line, and the true KM from the line’s intercept where (see Equation 11.36).

通常使用线性拟合来确定最终的slope,提升accuracy,缩小$K_{M}$的fit domain

Example

A clear example of a competitive inhibitor is shown in Figure 11.31.

The dinucleotide UpA is an excellent substrate for the enzyme ribonuclease(核糖核酸酶), which catalyzes hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the two nucleotides.

The substrate UpA and the structurally similar molecule UpcA are competitors for the enzyme ribonuclease, which catalyzes hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the two nucleotides.

But if the oxygen atom at the cleavage site in UpA is replaced by a $CH_{2}$ group, the molecule becomes the phosphonate analog UpcA, a strong competitive inhibitor.

The single difference between the substrate and the inhibitor is shown in magenta(品红).

2. Uncompetitive inhibition

Introduction

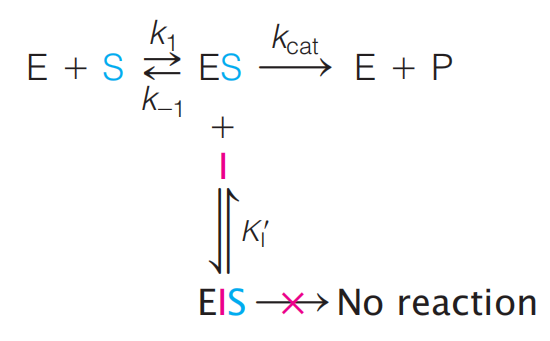

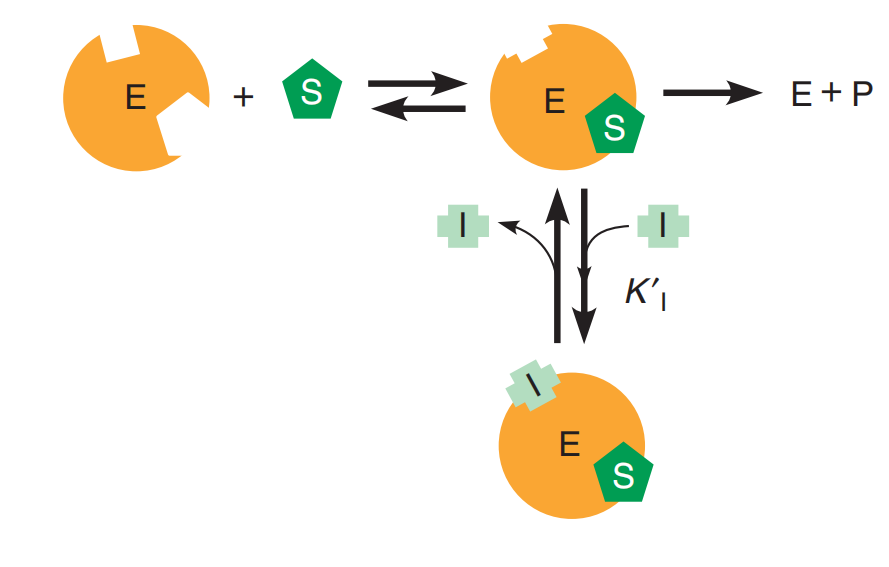

An uncompetitive inhibitor does not compete for the active site but affects the catalytic event. (改变了反应路径)

This form of inhibition occurs when a molecule or an ion can bind to a second site on an enzyme surface (not the active site) in such a way that it modifies $k_{cat}$

The simplest case to consider is one in which the inhibitor molecule binds only to the ES complex and does not interfere in any way with substrate binding, but completely prevents the catalytic step

Here we distinguish the equilibrium constant for inhibitor binding to free enzyme, $K_{I} \text{ and } K’{I}$, the equilibrium constant for inhibitor binding to the ES complex.

$$

K’{I} = \frac{[ES] [I]}{[EIS]}

$$

Deduction

$$

\because [E]{t} = [E] + [ES] + [ESI] \

k{1} [E] [S] = k_{-1} [ES] + k_{cat} [ES] \

K’_{I} = \frac{[ES] [I]}{[EIS]}

$$

$$

\therefore [E]{t} = [E] + [ES] + \frac{[ES][I]}{K’{I}}

$$

$$

\therefore [E]{t} - [ES] (1 + \frac{[I]}{K’{I}}) = [E]

$$

$$

\therefore [E][S] = K_{M} [ES] = [E]{t} [S] - [ES] [S] (1 + \frac{[I]}{K’{I}})

$$

$$

\therefore [ES] (K_{M} + (1 + \frac{[I]}{[K’{I}]}) [S] ) = [E]{t} [S]

$$

$$

\therefore v = k_{cat} [ES] = \frac{k_{cat} [E]{t} [S]}{K{M} + (1 + \frac{[I]}{[K’{I}]}) [S] } = \frac{V{max} [S]}{K_{M} + \alpha ‘ [S]} = \frac{V_{max}^{app} [S]}{K_{M}^{app} + [S]}

$$

Where

$$

\alpha ‘ = 1 + \frac{[I]}{[K’_{I}]}

$$

$$

V_{M}^{app} = \frac{V_{max}}{\alpha ‘}

$$

$$

K_{M} = \frac{K_{M}}{\alpha ‘}

$$

Effects of uncompetitive inhibition on enzyme kinetics

In the presence of an uncompetitive inhibitor both $V_{max}^{app}$ and $K_{M}^{app}$ appear to be reduced by a factor of $1/\alpha ‘$(More complex, less free enzyme)

Figure 11.33 (a)

At $[S] < K_{M}$ the effect of the inhibitor is minimal because as [S] decreases, v approaches $V_{max}[S]/K_{M}$.

在最开始的时候,$\alpha ‘ [S] + K_{M} \approx K_{M}$,因此两条曲线overlap

At $[S] > K_{M}$, the effect of the inhibitor on reducing $V_{max}$ is apparent because as [S] increases, v approaches $V_{max} / \alpha ‘$. (These effects cannot be reversed by increasing [S].)

Thus, as shown in Figure 11.33a, the v vs. [S] plots overlap at low [S] but diverge at higher [S].

Uncompetitive inhibition is distinguished from competitive inhibition by two observations:

uncompetitive inhibition cannot be reversed by increasing [S]

as shown in Figure 11.33b, the Lineweaver–Burk plot yields parallel rather than intersecting lines (because the factor drops out of the ratio to give a slope = $K_{M}/V_{max}$ for all values of $\alpha ‘$).

Example

This Uncompetitive inhibition behavior is found in the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (see Chapter 23) by tertiary amines(书胺) $R_{3} N$

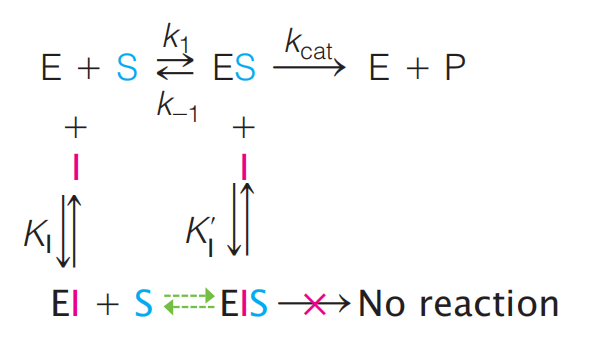

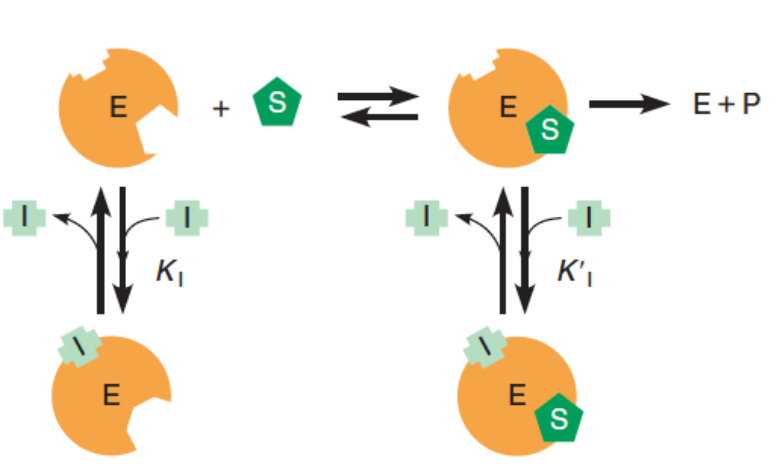

3. Mixed Inhibition

Introduction

- The inhibitor binds at a site on the enzyme surface different from that of the substrate.

- In this simplified example, the inhibitor binds to both free enzyme and the ES complex.

- EI has reduced substrate binding affinity compared to free enzyme.

- The EIS complex cannot carry out the catalytic event.

This form of inhibition occurs when a molecule or an ion can bind to both the free enzyme and the ES complex (see Figure 11.34):

Again, we distinguish the equilibrium constants $K_{I}$ and $K’_{I}$ respectively, for inhibitor binding to E and ES.

Substrate binding to the EI complex (green arrows in the scheme above) is typically significantly reduced compared to that for binding to free enzyme.

Thus, the process $EI + S \leftrightarrows EIS$ will not be considered here, although it is part of a complete thermodynamic analysis; in doing so, the derivation of the Michaelis–Menten equation for mixed inhibition is greatly simplified without significantly altering the conclusions of the analysis.

For this simplified case:

equation 11.38

$$

v = \frac{V_{max}^{app } [S]}{K_{M}^{app} + [S]} = \frac{V_{max}[S]}{\alpha K_{M} + \alpha ‘ [S]}

$$

此时

$$

V_{max}^{app} = \frac{V_{max}}{\alpha’} \

V_{max}^{app} \text{ decreased }

$$

$$

K_{M}^{app} = \frac{\alpha K_{M}}{\alpha’} = \frac{1 + \frac{[I]}{K_{I}}}{1 + \frac{I}{K’{I}}}K{M} \

K_{M}^{app} \text{ change depends on }K_{I} \text{ and } K’_{I}

$$

In most cases, the inhibitor has a greater affinity for the free enzyme than for the ES complex; thus, $\alpha $ is typically greater than $\alpha’$

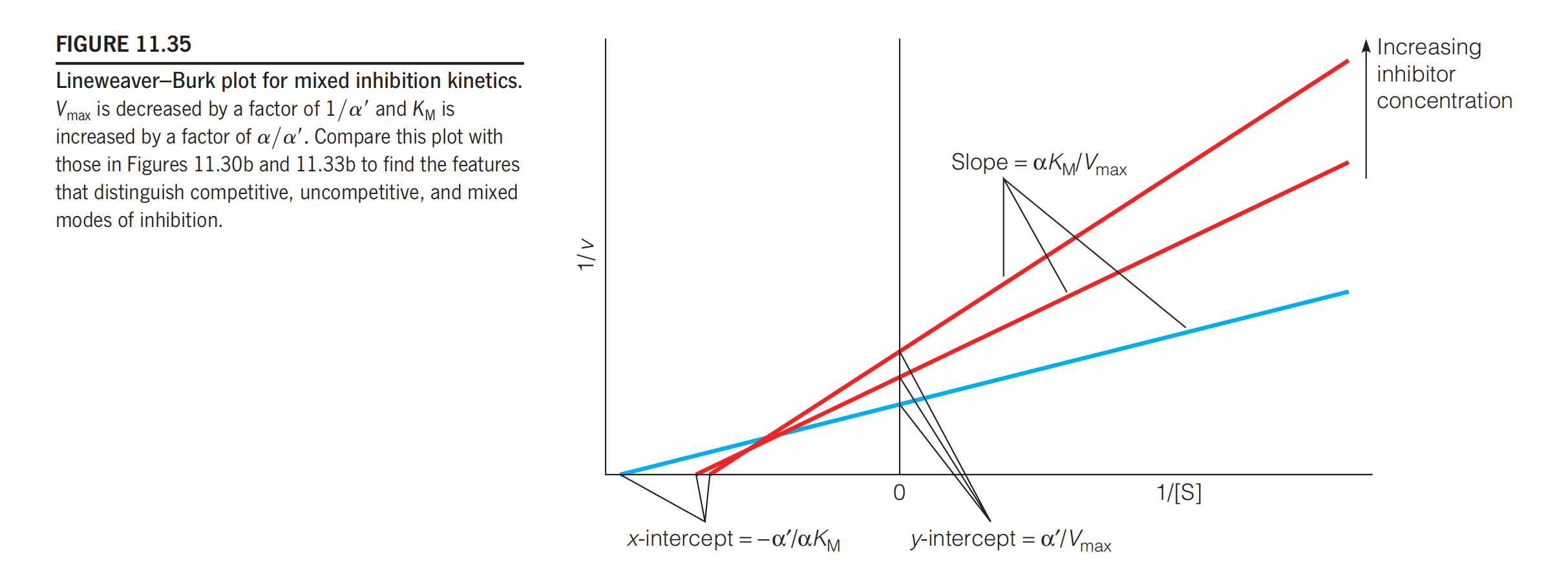

Figure 11.35

Figure 11.35 shows that the Lineweaver–Burk plot for mixed inhibition reflects this decreased $V_{max}$ and increased $K_{M}$ and is distinct from similar plots for competitive and uncompetitive modes of inhibition.

Finally, mixed inhibitors effectively reduce v at low and high values of [S].

- At $[S] < K_{M}$, v approaches $V_{max} [S] / \alpha K_{M}$

- At $[S] > K_{M}$, v approaches $V_{max} / \alpha’ $

Thus, $V_{max}^{app}$ will be less than $V_{max }$ for all values of [S].

noncompetitive inhibition

If $\alpha = \alpha’$, then it is a noncompetitive inhibition

Substrate binding doesn’t affect inhibitor binding.

此时

$$

K_{M}^{app} = K_{M}

$$

$$

V_{max}^{app} < V_{max}

$$

Irreversible Inhibition

Some substances combine covalently with enzymes to inactivate them irreversibly.

Because the covalent binding is too strong, so this kind of inhibition is irreversible

In most cases, such substances react with some functional group in the active site to leave it catalytically inactive or to block substrate binding.

1. Example

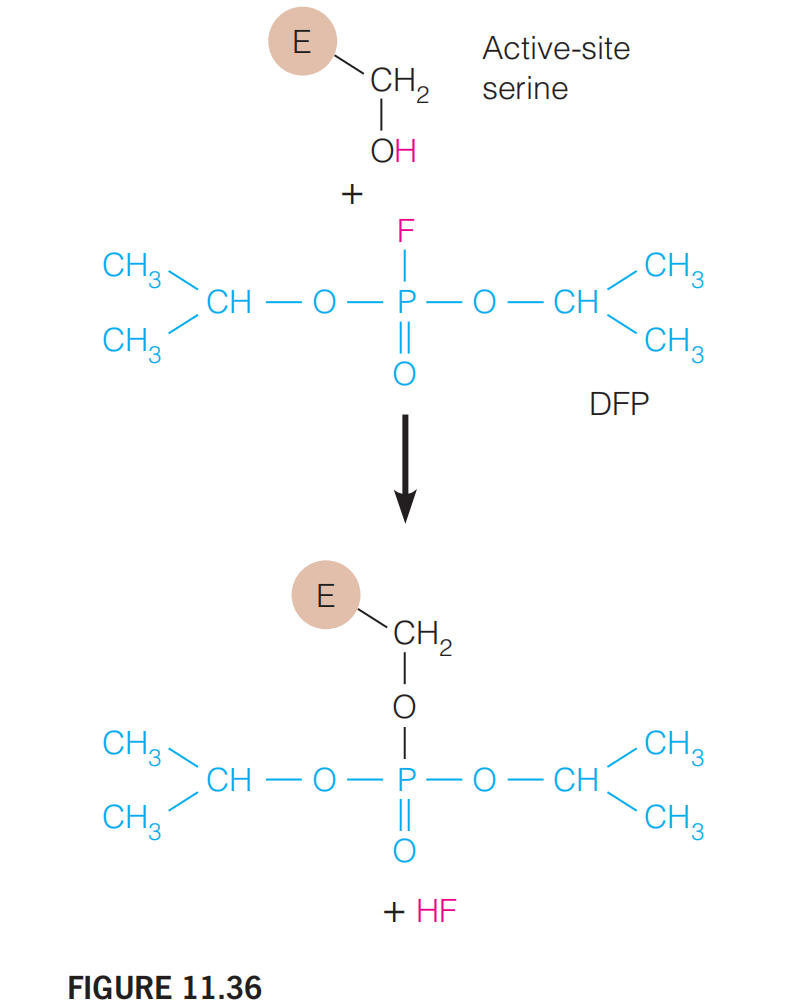

DFP

Irreversible inhibition by adduct formation:

Diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP) reacts with a serine group on a protein to form a covalent adduct. (Figure 11.36)

The covalent bond renders the catalytically important serine ineffective in catalysis.

The adduct also may block substrate binding to the active site.

For such irreversible inhibitors to react selectively with a critical residue, they must bind strongly to the active site. Many do so because they are transition state analogs.

TPCK

N-tosyl-L-phenylalaninechloromethyl ketone (TPCK) (see Table 11.7)

TPCK is an excellent inhibitor for chymotrypsin because the phenyl group fits nicely into the active site pocket, positioning the chlorine for nucleophilic displacement by a nitrogen of the imidazole ring of His 57.

(1) Use of TPCK

- A biochemist who is using chymotrypsin to hydrolyze a protein can stop the reaction instantly at any point by simply adding TPCK

- Another use for such substances is to label active site residues of an enzyme specifically to aid in their identification. When irreversible inhibitors are used in this way, they are often called affinity labels.

In some cases an affinity label is unreactive until it is acted on by the enzyme, at which point it binds irreversibly.

Such substances are called suicide inhibitors because the enzyme “kills” itself by processing the inhibitor from a benign to a reactive form.

In biochemistry, suicide inhibition, also known as suicide inactivation or mechanism-based inhibition, is an irreversible form of enzyme inhibition that occurs when an enzyme binds a substrate analog and forms an irreversible complex with it through a covalent bond during the normal catalysis reaction. The inhibitor binds to the active site where it is modified by the enzyme to produce a reactive group that reacts irreversibly to form a stable inhibitor-enzyme complex.

Example: Penicillin

Natural Toxins

Many natural toxins are irreversible enzyme inhibitors.

The alkaloid physostigmine (see Table 11.7), which is contained in calabar beans, is toxic because it is a potent inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase (乙酰胆碱酯酶).

The penicillin antibiotics also act as irreversible inhibitors of serine-containing enzymes used in bacterial cell wall synthesis

二、Cofactors, Vitamins, and Essential Metals

For some kinds of biological processes, the chemical potential of amino acid side chains alone is not sufficient.

A protein may require the help of some other small molecule or ion to carry out the reaction. The ions or molecules that are bound to enzymes for this purpose are called cofactors or coenzymes.

Like enzymes, cofactors are not irreversibly changed during catalysis; they are either unmodified or regenerated, as discussed above in the case of dihydrofolate reductase, which uses the NADPH cofactor.

Cofactors and coenzymes can be

- Essential ions (mostly metal ions)

- Small molecules (organic compounds)

$$

\text{Apoenzyme(protein only, inactive) + Cofactor = Holoenzyme(active)}

$$

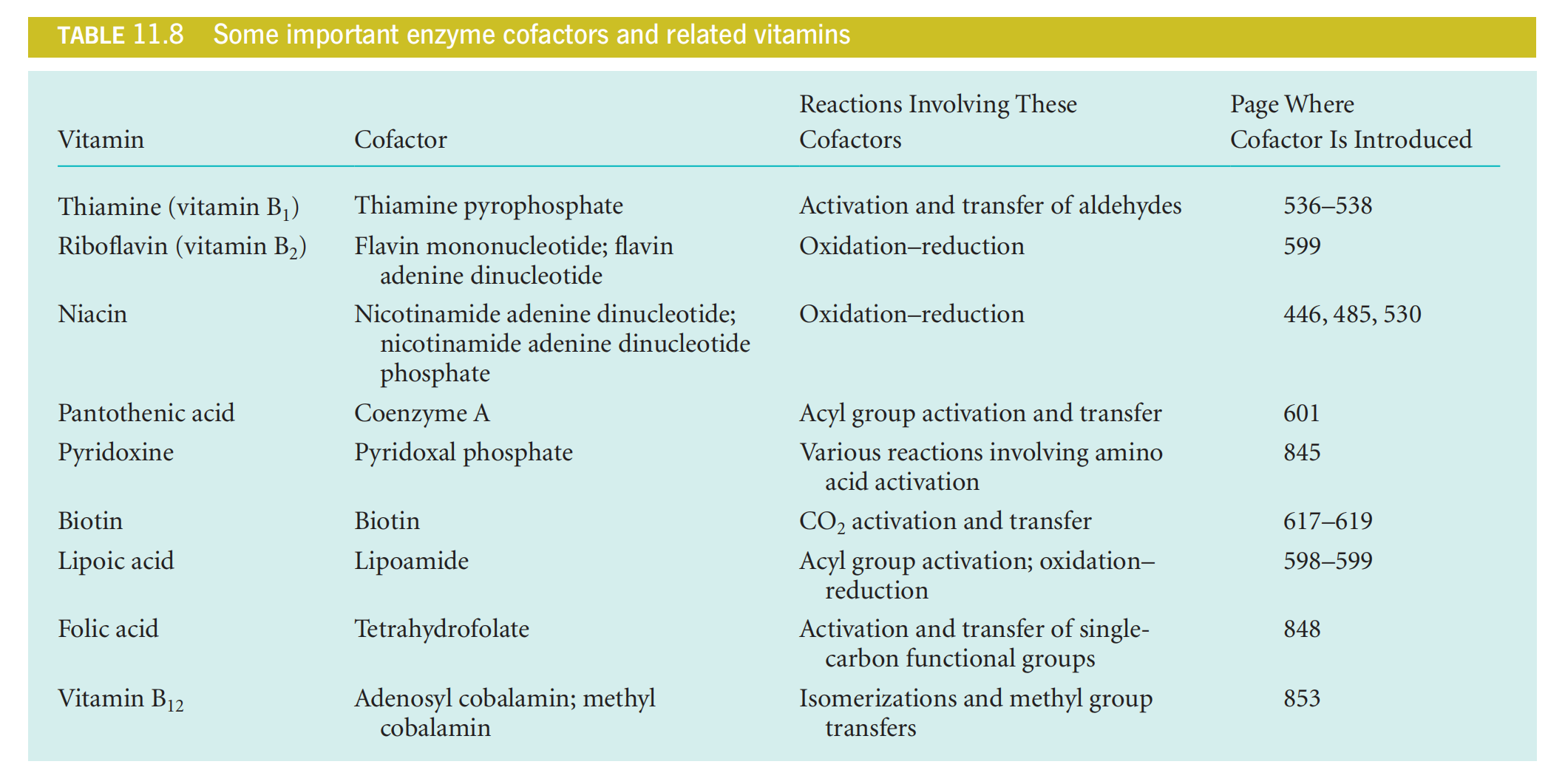

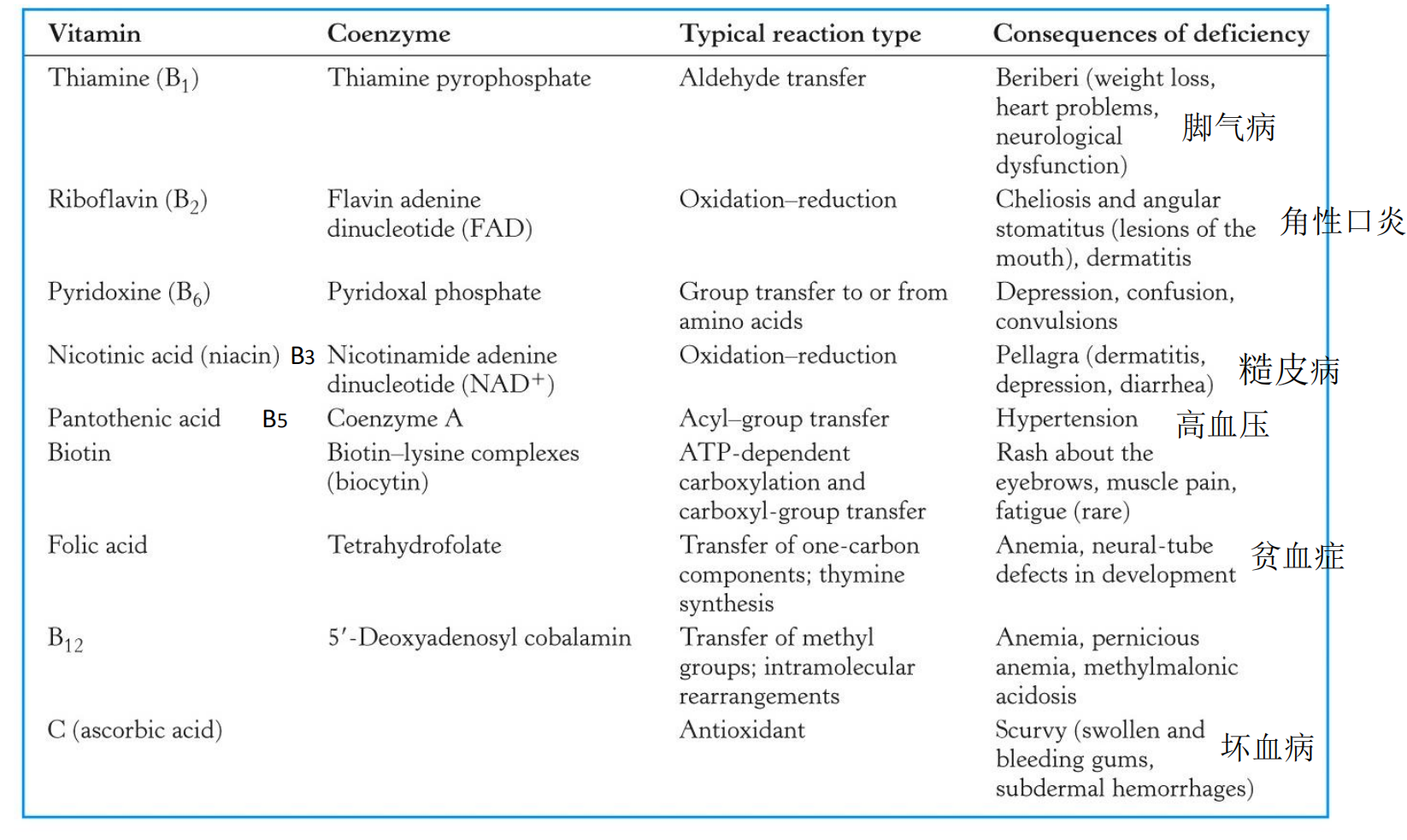

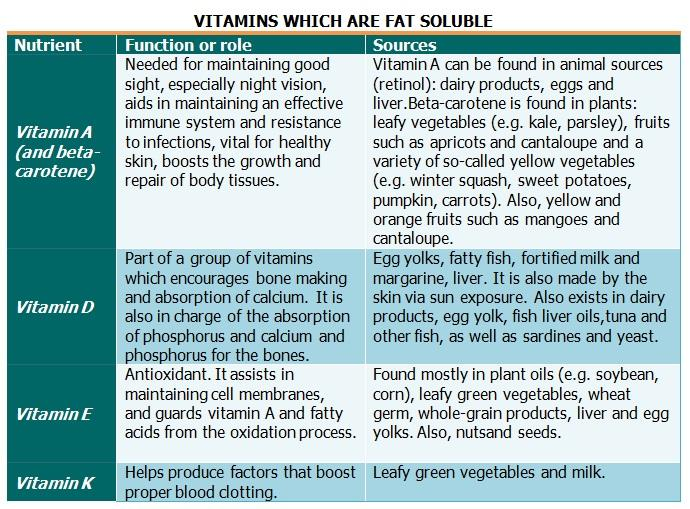

Vitamins

1. Functions

Cofactors often have complex organic structures that cannot be synthesized by some organisms—mammals in particular. The water-soluble vitamins, those usually referred to as the vitamin-B complex, are metabolic precursors (前体) of several cofactors.

This is why such vitamins are so important in metabolism.

Table 11.8 lists a number of important enzyme cofactors, together with their related vitamins, the kinds of reactions they are associated with, and where in this textbook you will find detailed descriptions and discussion.

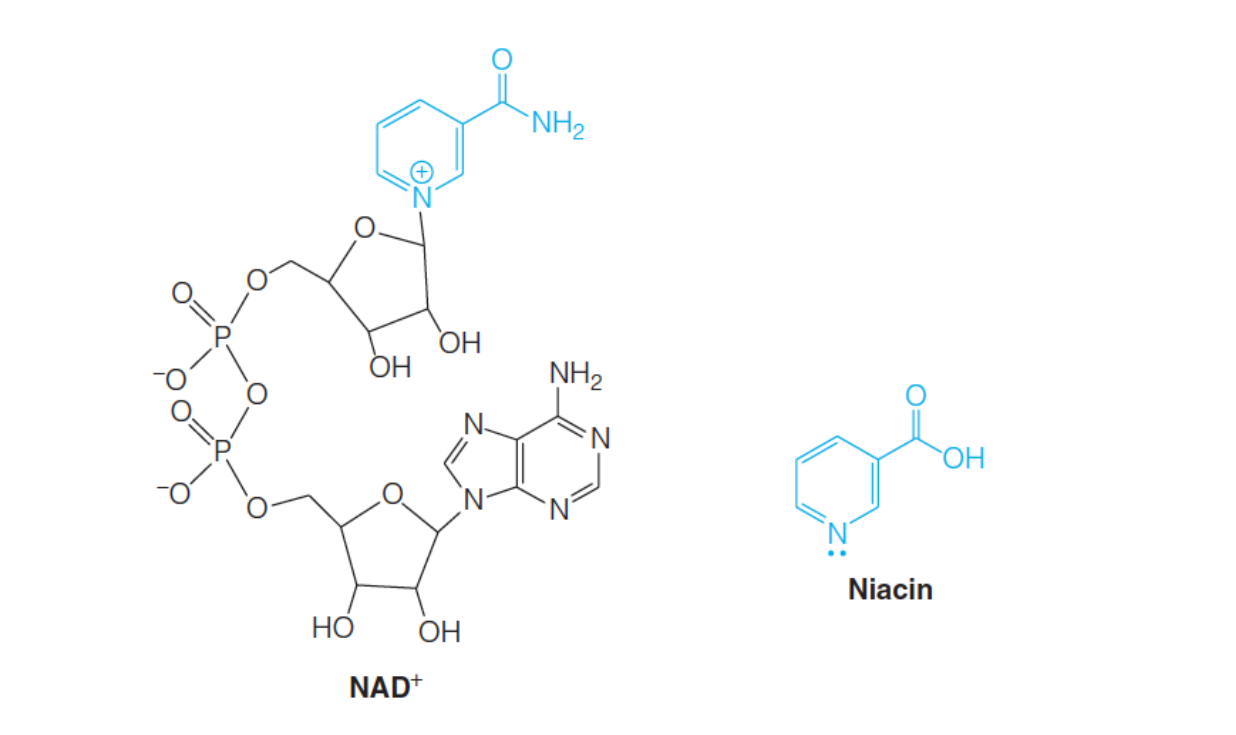

2. Example: niacin and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)

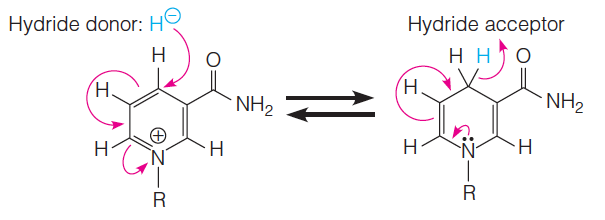

The nicotinamide(烟碱) portion is the metabolically relevant part of $NAD^{+}$, because it is capable of being reduced and thus can serve as an oxidizing agent to which two electrons and a proton are added to the nicotinamide ring:

$$

NAD^{+} + 2e^{-} + H^{+} \rightarrow NADH

$$

The reaction is reversible (i.e., NADH acts as a reducing agent in several reactions) and is formally a hydride ion transfer:

$$

NAD^{+} + H^{-} \rightleftarrows NADH

$$

Here, R stands for the remainder of the molecule.

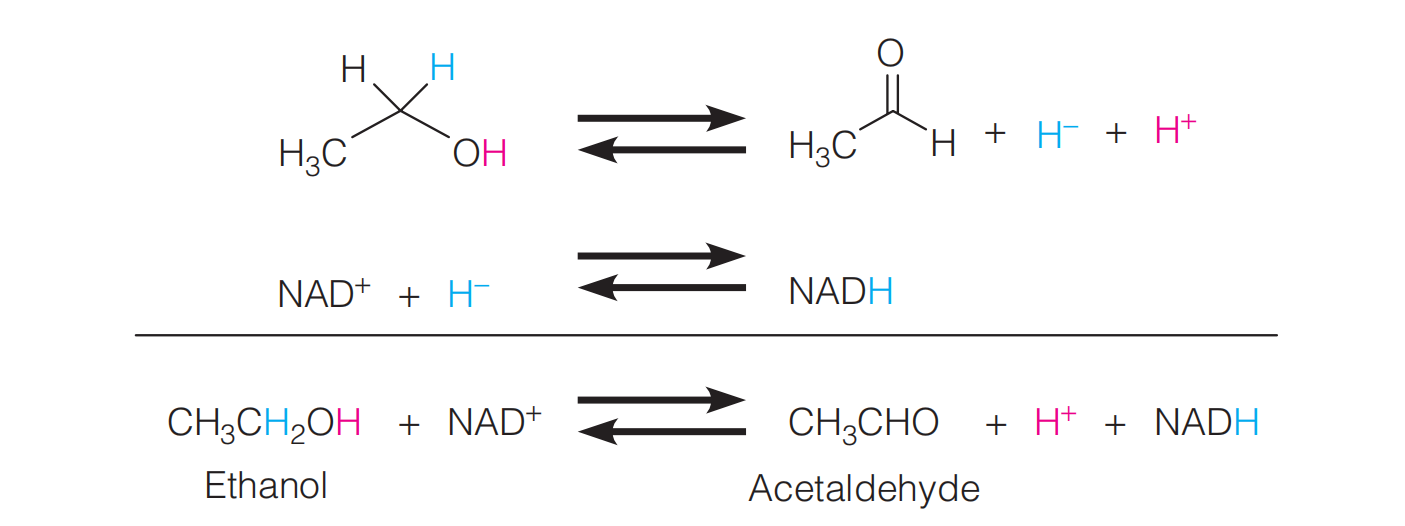

A typical reaction in which $NAD^{+}$ acts as an oxidizing agent is the conversion of alcohols to aldehydes(乙醛) or ketones (酮类)(for example, by the alcohol dehydrogenase of liver):

3. Stereospecific 立体化学特异性

Introduction

Simple catalyst催化形成的产物可能是多种立体异构体,但是酶催化的反应产物大多具有特定的立体结构

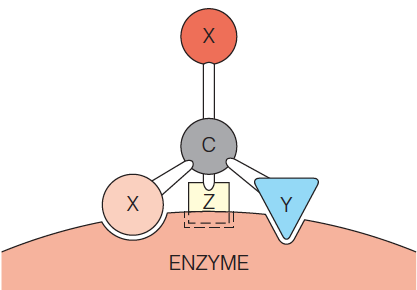

This figure shows how the asymmetric surface of an enzyme can confer stereospecificity in the reaction of a symmetric substrate.

The asymmetric surface of an enzyme can confer stereospecificity in the reaction of a symmetric substrate.

If the substrate molecule $X_{2} CYZ$ makes at least make three contacts with unique complementary groups on the enzyme, its two X atoms are no longer equivalent.

Only a specific one of the two X atoms can contact the surface properly.

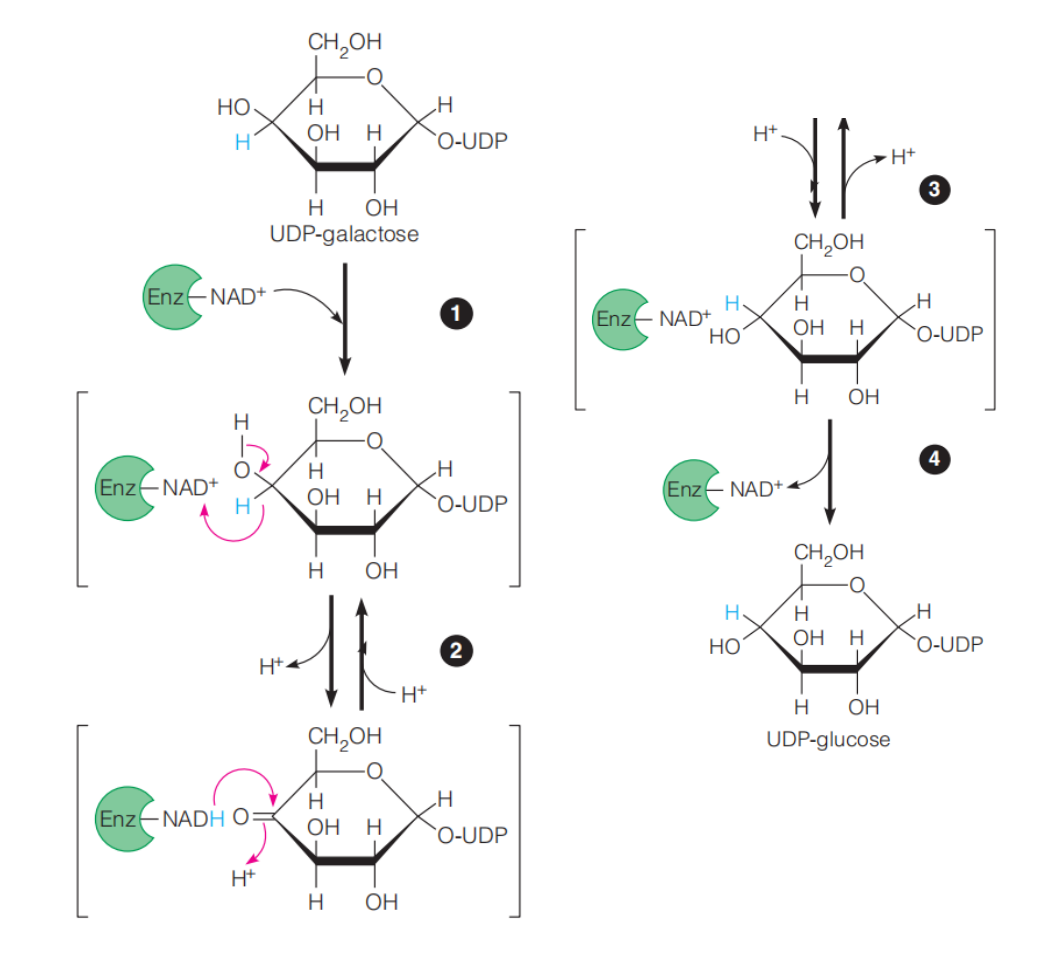

Example: UDP-galactose 4-epimerase

Proposed mechanism for UDP-galactose epimerase:

- UDP-galactose is bound to the enzyme, which carries the coenzyme NAD+ .

- Hydride is transferred to NAD+ from C4 of the galactose ring to produce the carbonyl intermediate.

- Hydride is then transferred back to C4 to give the opposite stereochemistry.

- The product, UDP-glucose, is released.

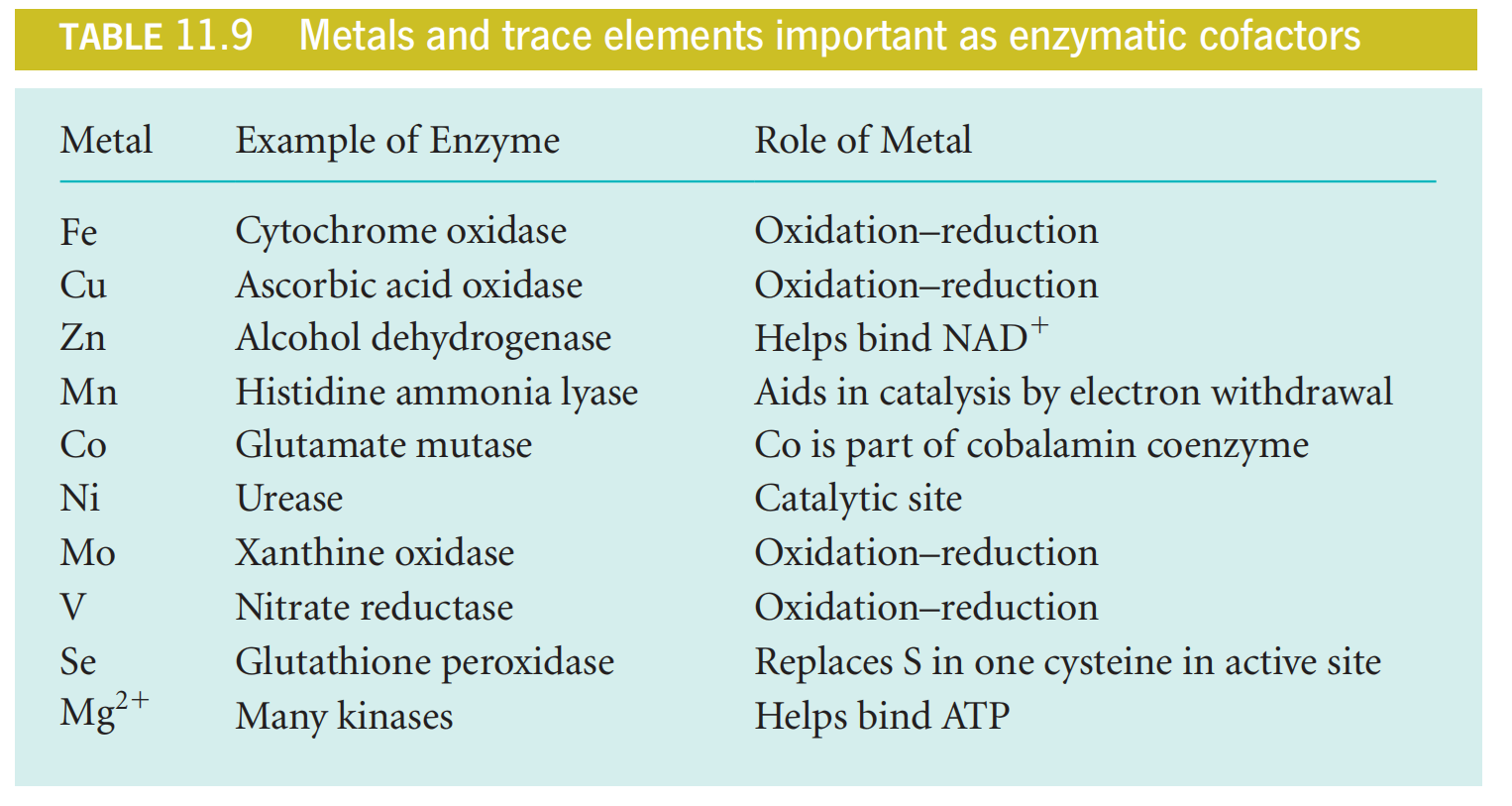

Metal Ions in Enzymes

1. Introduction

Many enzymes contain one or more metal ions, usually held by coordinate covalent bonds from amino acid side chains, but sometimes bound by a prosthetic group like heme.

Such enzymes are called metalloenzymes(金属酶)

The bound ion acts in much the same way as a coenzyme, conferring on the metalloenzyme a property it would not possess in its absence.

As Table 11.9 shows, the roles these ions play are diverse.

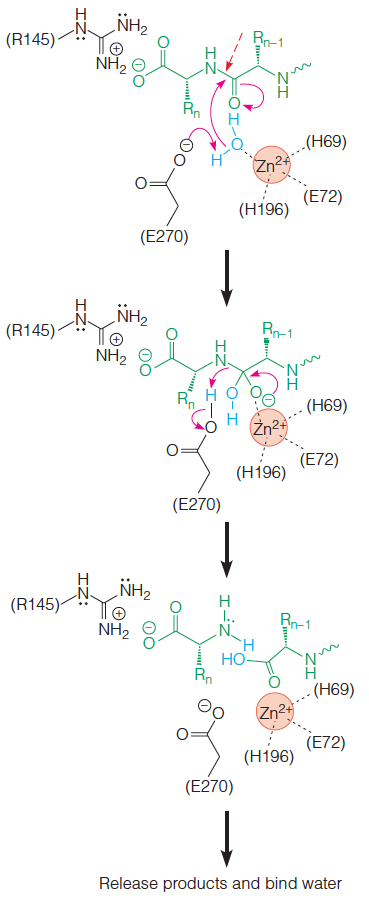

2. Example: carboxypeptidease A.

The zinc ion in carboxypeptidase A binds the water molecule that attacks the carbonyl of the scissile bond and also acts as an electrostatic catalyst (Figure 11.39)

The zinc ion stabilizes the tetrahedral oxyanion in the transition state and the intermediate state, in much the same way as the oxyanion hole serves this function in chymotrypsin (see Figure 11.19 for comparison).

Carboxypeptidase A usually refers to the pancreatic exopeptidase(胰外肽酶) which hydrolyzes

peptide bonds of C-terminal residues with aromatic or aliphatic( 脂肪族的) side chains.

3. Example: Catalase

In other cases, the metal in a metalloenzyme serves as a redox reagent. We have mentioned the example of the heme-iron–containing enzyme catalase, which catalyzes the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide, a potentially destructive agent in cells.

Because the reaction involves both reduction and oxidation of $H_{2} O_{2}$, the $Fe^{2+}$ is reversibly oxidized and reduced, acting as an electron exchanger.

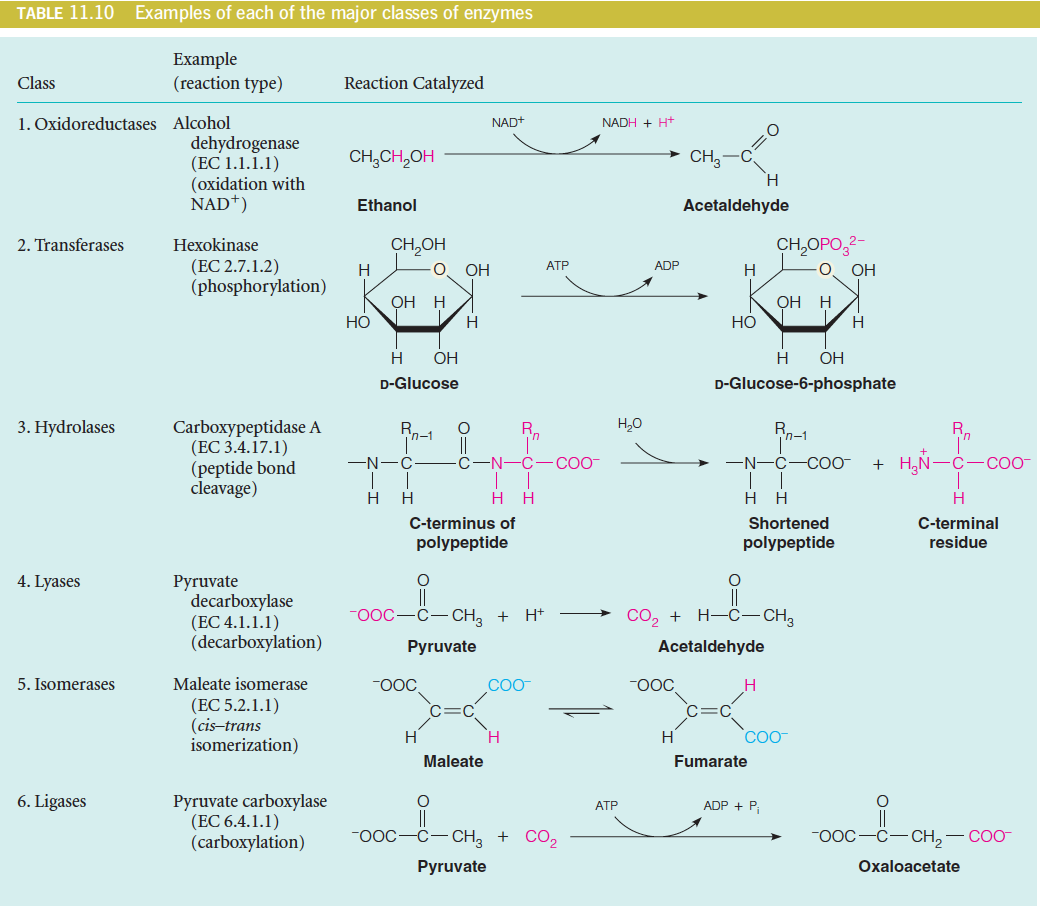

三、The Diversity of Enzymatic Function

Classification of Protein Enzymes

A rational naming and numbering system has been devised by the Enzyme Commission of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB).

Enzymes are divided into six major classes as follows:

1. Oxidoreductases catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions.

2. Transferases catalyze transfer of functional groups from one molecule to

another.

3. Hydrolases catalyze hydrolytic cleavage.

4. Lyases catalyze removal of a group from or addition of a group to a double

bond, or other cleavages involving electron rearrangement.

5. Isomerases catalyze intramolecular rearrangement.

6. Ligases catalyze reactions in which two molecules are joined.

The IUBMB Enzyme Commission (EC) has given each enzyme a number with four parts, such as: EC 3.4.21.5. The first three numbers define major class, subclass, and sub-subclass, respectively.

Nonprotein Biocatalysts: Catalytic Nucleic Acids

Some RNA molecules, called ribozymes, can act as enzymes.

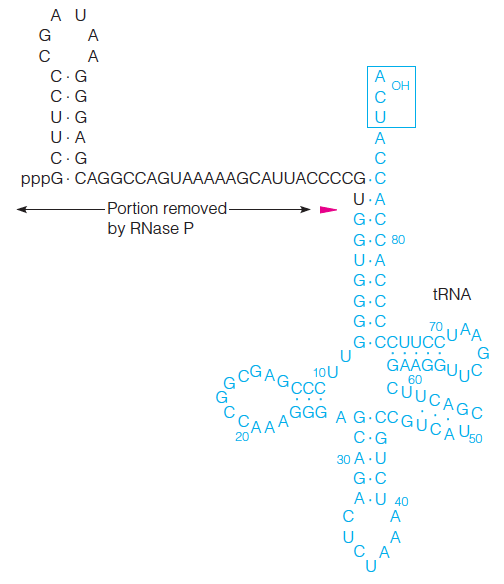

The production of tRNA from pre-tRNA is catalyzed by an RNA–protein complex called ribonuclease P.

The RNA portion of ribonuclease P can by itself catalyze the hydrolysis of the specific phosphodiester bond indicated by the red wedge.