L9 Part1 Injestive Behaviour

Learning Objectives

- Explain the characteristics of a regulatory mechanism.

- Describe the fluid compartments of the body.

- Explain the control of osmometric thirst and volumetric thirst and the role of angiotensin.

- Describe characteristics of the two nutrient reservoirs and the absorptive and fasting phases of metabolism.

- Discuss the signals from the environment, the stomach, and the metabolism that begin a meal.

- Discuss the long-term and short-term factors that stop a meal.

- Describe research on the role of the brain stem and hypothalamus in hunger and satiety.

- Discuss the social and physiological factors that contribute to obesity.

- Discuss surgical, behavioral, and pharmacological treatments for obesity.

- Discuss the physiological factors that may contribute to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

一、Physiological Regulatory Mechanisms

Homeostasis

As the French physiologist Claude Bernard (1813–1878) said, “The constancy of the internal milieu is a necessary condition for a free life.”

This famous quotation says succinctly what organisms must do to be able to exist in environments that are hostile to the living cells that compose them (that is, to live a “free life”): They must provide a barrier between their cells and the external environment—in the case of mammals, this barrier consists of skin and mucous membrane. Within the barrier, they must regulate the nature of the internal fluid that bathes the cells

Regulation of the fluid that bathes our cells is part of a process called homeostasis (“similar standing”).

This chapter discusses:

- How do the mammals achieve homeostatic control of the vital characteristics of our extracellular fluid through our ingestive behavior : intake of food, water, and minerals such as sodium.

- First, we will examine the general nature of regulatory mechanisms;

- Then we will consider drinking and eating, as well as the neural mechanisms that are responsible for these behaviors;

- Finally, we will look at some research on the eating disorders

Physiological Regulatory Mechanisms

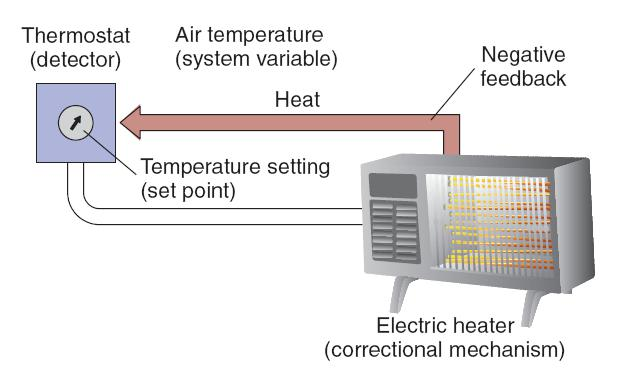

A physiological regulatory mechanism maintains the constancy of some internal characteristic of the organism in the face of external variability—for example, keeping body temperature constant despite changes in the ambient temperature

- A regulatory mechanism contains four essential features:

- the system variable (the characteristic to be regulated),

- a set point (the optimal value of the system variable),

- a detector that monitors the value of the system variable,

- a correctional mechanism that restores the system variable to the set point

Negative feedback is a process whereby the effect produced by an action serves to diminish or terminate that action;

- a characteristic of regulatory systems

1. An Example of a Regulatory System

An example of a regulatory system is a room in which temperature is regulated by a thermostatically controlled heater. The system variable is the room’s air temperature, and the detector for this variable is a thermostat. This device can be adjusted so that contacts of a switch will be closed when the temperature falls below a preset value (the set point). Closure of the contacts turns on the correctional mechanism—the coils of the heater.

If the room cools below the set point of the thermostat, the thermostat turns the heater on, and the heater warms the room. The rise in room temperature causes the thermostat to turn the heater off. Because the activity of the correctional mechanism (heat production) feeds back to the thermostat and causes it to turn the heater off, this process is called negative feedback .

Negative feedback is an essential characteristic of all regulatory systems.

二、Drinking

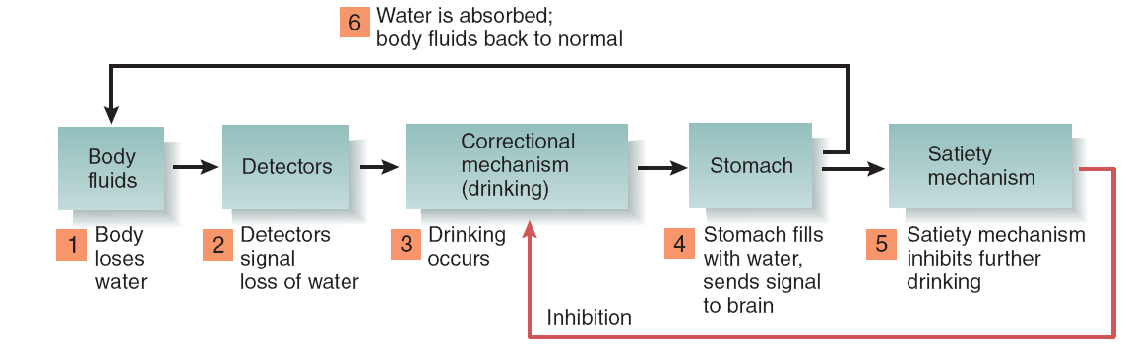

Ingestive behaviors are correctional mechanisms that replenish the body’s depleted stores of water or nutrients.

Because of the delay between ingestion and replenishment of the depleted stores, ingestive behaviors are controlled by satiety mechanisms as well as by detectors that monitor the system variables.

For example, suppose you spend some time in a hot, dry environment and lose body water. The loss of water causes internal detectors to initiate the correctional mechanism: drinking.

You quickly drink a glass or two of water and then stop. What stops your ingestive behavior? The water is still in your digestive system, not yet in the fluid surrounding your cells, where it is needed. Therefore, although drinking was initiated by detectors that measure your body’s need for water, it was stopped by other means. There must be a satiety mechanism that says, in effect, “Stop—this water, when absorbed by the digestive system into the blood, will eventually replenish the body’s need.”

Satiety mechanisms monitor the activity of the correctional mechanism (in this case, drinking), not the system variables themselves. When a sufficient amount of drinking occurs, the satiety mechanisms stop further drinking in anticipation of the replenishment that will occur later.

1. Satiety mechanism

Satiety mechanism:

A brain mechanism that causes cessation of hunger or thirst, produced by adequate and available supplies of nutrients or water.

2. Outline of the System that Controls Drinking

Some Facts About Fluid Balance

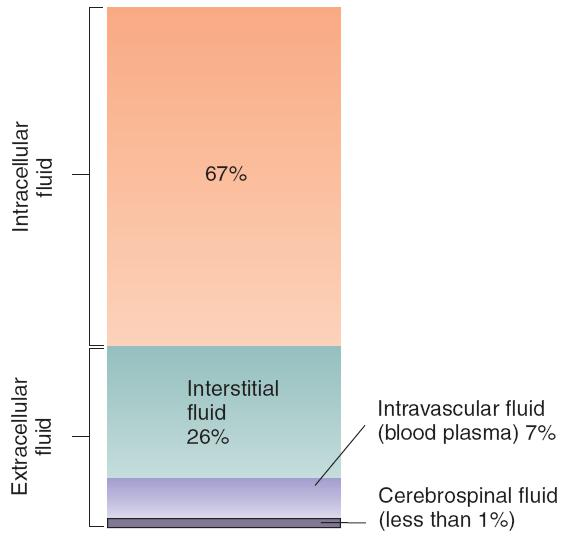

Intracellular fluid

- The fluid contained within cells.

Extracellular fluid

- All body fluids outside cells: interstitial fluid, blood plasma (Intravascular fluid), and cerebrospinal fluid.

- Interstitial fluid

- The fluid that bathes the cells, filling the space between the cells of the body (the “interstices”).

- intravascular fluid:

- The fluid found within the blood vessels.

The Relative Size of the Body’s Fluid Compartments

Two of the body’s fluid compartments must be kept within precise limits: the intracellular fluid and the intravascular fluid.

The intracellular fluid is controlled by the concentration of solutes in the interstitial fluid.

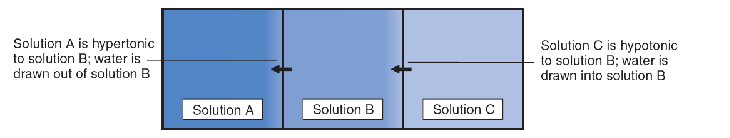

Normally, the interstitial fluid is isotonic (from isos, “equal,” and tonos, “tension”) with the intracellular fluid. That is, the concentration of solutes in the cells and in the interstitial fluid that bathes them is balanced, so that water does not tend to move into or out of the cells.

If the interstitial fluid loses water (becomes more concentrated, or hypertonic ), water will be pulled out of the cells. On the other hand, if the interstitial fluid gains water (becomes more dilute, or hypotonic ), water will move into the cells.

Either condition endangers cells; a loss of water deprives them of the ability to perform many chemical reactions, and a gain of water can cause their membranes to rupture. Therefore, the concentration of the interstitial fluid must be closely regulated.

Isotonic 等渗

- Equal in osmotic pressure to the contents of a cell. A cell placed in an isotonic solution neither gains nor loses water.

Hypertonic 高渗

- The characteristic of a solution that contains enough solute that it will draw water out of a cell placed in it, through the process of osmosis.

Hypotonic 低渗

- The characteristic of a solution that contains so little solute that a cell placed in it will absorb water, through the process of osmosis.

Solute Concentration :

- The figure shows the effects of differences in solute concentration on the movement of water molecules.

The volume of the blood plasma must be closely regulated because of the mechanics of the heart’s operation. If the blood volume falls too low, the heart can no longer pump the blood effectively; if the volume is not restored, heart failure will result. This condition is called hypovolemia , literally “low volume of the blood” (-emia comes from the Greek haima, “blood”). The body’s vascular system can make some adjustments for loss of blood volume by contracting the muscles in smaller veins and arteries, thereby presenting a smaller space for the blood to fill, but this correctional mechanism has definite limits.

Hypovolemia 血容量过低

- Reduction in the volume of the intravascular fluid.

The two important characteristics of the body fluids—the solute concentration of the intracellular fluid and the volume of the blood—are monitored by two different sets of receptors.

- A single set of receptors would not work because it is possible for one of these fluid compartments to be changed without affecting the other.

- For example, a loss of blood obviously reduces the volume of the intravascular fluid, but it has no effect on the volume of the intracellular fluid.

- On the other hand, a salty meal will increase the solute concentration of the interstitial fluid, drawing water out of the cells, but it will not cause hypovolemia.

Thus, the body needs two sets of receptors, one measuring blood volume and another measuring cell volume.

Two Types of Thirst

Loss of water from either the intracellular or intravascular fluid compartments stimulates drinking, researchers have adopted the terms osmometric thirst (渗透性口渴) and volumetric thirst(体积性口渴) to describe them.

Thirst means different things in different circumstances.

- Its original definition referred to a sensation that people say they have when they are dehydrated.

- Because we do not know how other animals feel, thirst simply means a tendency to seek water and to ingest it.

1. Osmometric thirst

Thirst produced by an increase in the osmotic pressure of the interstitial fluid relative to the intracellular fluid, thus producing cellular dehydration (the cells, and they shrink in volume).

The detector is responding to (metering) changes in the concentration of the interstitial fluid that surrounds them.

Osmoreceptor 渗透压感受器

A neuron that detects changes in the solute concentration of the interstitial fluid that surrounds it.

The existence of neurons that respond to changes in the solute concentration of the interstitial fluid was first hypothesized by Verney (1947). Verney suggested that these detectors, which he called osmoreceptors , were neurons whose firing rate was affected by their level of hydration. That is, if the interstitial fluid surrounding them became more concentrated, they would lose water through osmosis. The shrinkage would cause them to alter their firing rate, which would send signals to other parts of the brain.

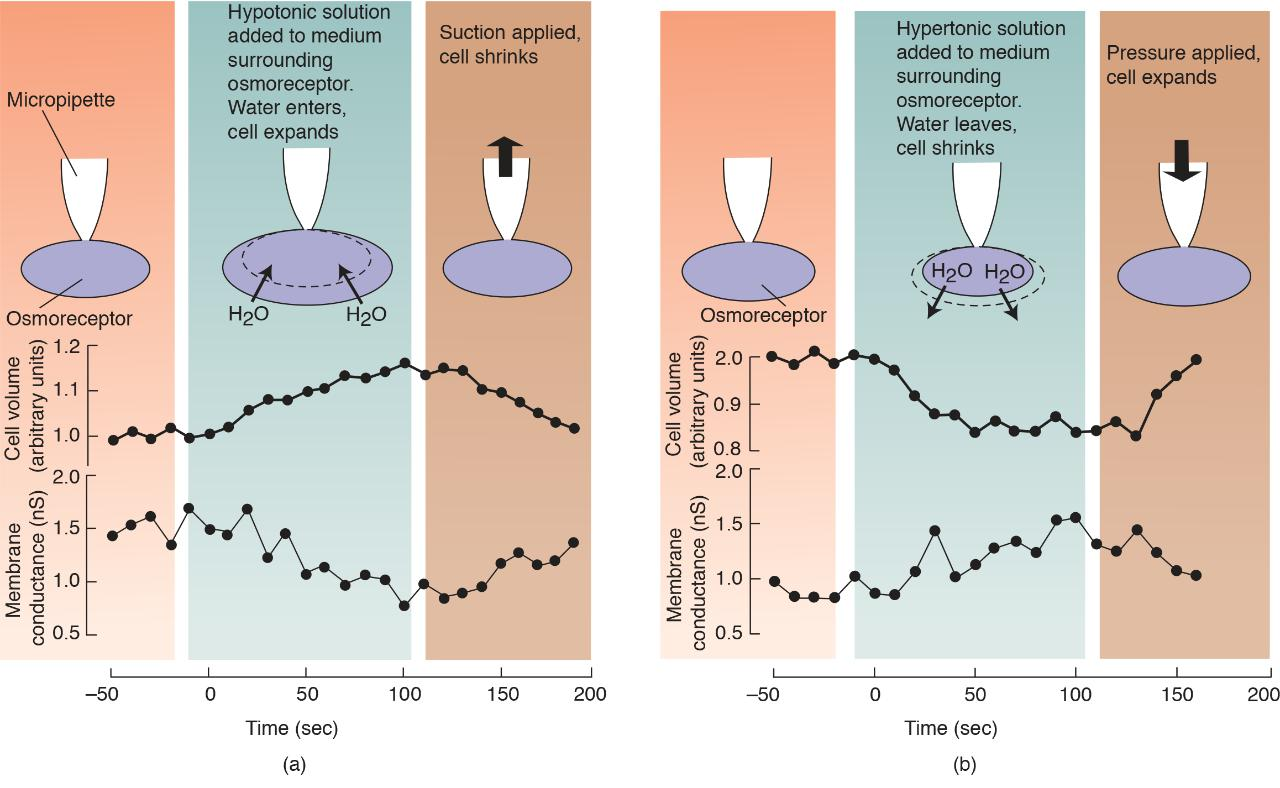

Action of an Osmoreceptor

(a) When a hypotonic solution was added to the culture medium of an isolated osmoreceptor, the cell volume increased and the membrane potential decreased. When suction was then applied through the micropipette, the cell volume decreased and the membrane potential increased. (b) Opposite effects were seen when cell volume was reduced by a hypertonic solution and then increased by applying pressure through the micropipette.

Actin filaments in brain osmoreceptors detect changes in solute concentration in the interstitial fluid when the cell membrane expands or contracts. Changes in cell volume cause changes in the membrane potential, which serve as the signal for osmometric thirst.

Most researchers now believe that osmoreceptors responsible for osmometric thirst are located in the region of the anterior hypothalamus that borders the anteroventral tip of the third ventricle (the AV3V).

Buggy et al. (1979) found that injections of hypertonic saline directly into AV3V produced drinking.

When we eat a salty meal, we incur a pure osmometric thirst.

The salt is absorbed from the digestive system into the blood plasma; hence, the blood plasma becomes hypertonic. This condition draws water from the interstitial fluid, which makes this compartment become hypertonic as well and thus causes water to leave the cells. As the blood plasma increases in volume, the kidneys begin excreting large amounts of both sodium and water. Eventually, the excess sodium is excreted, along with the water that was taken from the interstitial and intracellular fluid. The net result is a loss of water from the cells. At no time does the volume of the blood plasma fall.

Human study

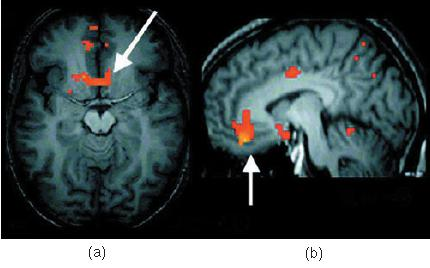

A functional imaging study by Egan et al. (2003) found that the human AV3V also appears to contain osmoreceptors.

The investigators administered intravenous injections of hypertonic saline to normal subjects while their brains were being scanned. They observed strong activation of several brain regions, including the AV3V and the anterior cingulate cortex.

When the subjects were permitted to drink water, they did so and almost immediately reported that their thirst had been satisfied. Simultaneously, the activity in the anterior cingulate cortex returned to baseline values.

However, the activity in the AV3V remained high.

These results suggest that the activity of the anterior cingulate cortex reflected the subjects’ thirst, which was immediately relieved by a drink of water. (This region is related to people’s perception of the unpleasantness of painful stimuli.)

In contrast, the continued activity in the AV3V reflected the fact that the blood plasma was still hypertonic. After all, it takes around 20 minutes for a drink of water to be absorbed into the general circulation.

Satiety is an anticipatory mechanism, triggered by the act of drinking. The fall in the activity of the anterior cingulate cortex appears to reflect the activation of this satiety mechanism.

Osmometric Thirst in Humans:

- Functional MRI scans show brain activation produced by osmometric thirst. (a) Activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and hypothalamus, corresponding to a sensation of thirst. (b) Activation in the lamina terminalis, the location of the brain’s osmoreceptors.

Two other functional imaging studies (Farrell et al., 2006; Xiao et al., 2006) confirm that thirst activates the anterior cingulate cortex.

An anatomical tracing study by Hollis et al. (2008) found that in rats, osmoreceptive neurons in the AV3V were connected to the cingulate cortex via the dorsal midline nuclei of the thalamus. This pathway between the osmoreceptors in the AV3V and the cingulate cortex is probably responsible for the activation seen in the functional imaging studies.

2. Volumetric Thirst

Volumetric thirst occurs when the volume of the blood plasma (the intravascular volume) decreases.

As we saw earlier, when we lose water through evaporation, we lose it from all three fluid compartments: intracellular, interstitial, and intravascular. Thus, evaporation produces both volumetric thirst and osmometric thirst.

In addition, loss of blood, vomiting, and diarrhea all cause loss of blood volume (hypovolemia) without depleting the intracellular fluid.

- Volumetric thirst is produced by hypovolemia.

Loss of blood causes pure volumetric thirst. From the earliest recorded history, reports of battles note that the wounded survivors called out for water. In addition, because hypovolemia involves a loss of sodium as well as water (that is, the sodium that was contained in the isotonic fluid that was lost), volumetric thirst leads to a salt appetite.

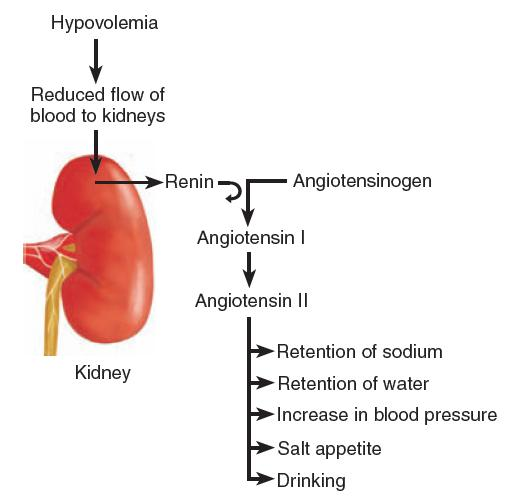

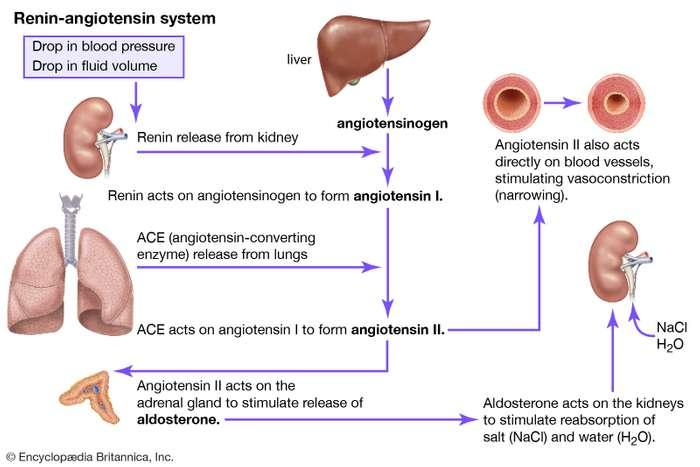

Role of Angiotensin 血管紧张素

The kidneys contain cells that are able to detect decreases in the flow of blood to the kidneys.

- The usual cause of a reduced flow of blood is a loss of blood volume; thus, these cells detect the presence of hypovolemia.

- When the flow of blood to the kidneys decreases, these cells secrete an enzyme called renin(肾素).

- Renin enters the blood, where it catalyzes the conversion of a protein called angiotensinogen into a hormone called angiotensin(血管紧张素).

There are two forms of angiotensin. Angiotensinogen becomes angiotensin I, which is quickly converted by an enzyme to angiotensin II. The active form is angiotensin II, which is abbreviate as AII.

- Detection of Hypovolemia by the Kidney and the Renin–Angiotensin System:

Angiotensin II has several physiological effects:

- It stimulates the secretion of hormones by the posterior pituitary gland and the adrenal cortex that cause the kidneys to conserve water and sodium;

- It increases blood pressure by causing muscles in the small arteries to contract.

Angiotensin II has two behavioral effects:

- It initiates both drinking and a salt appetite. Therefore, a reduction in the flow of blood to the kidneys causes water and sodium to be retained by the body, helps to compensate for their loss by reducing the size of the blood vessels, and encourages the animal to find and ingest both water and salt

Renin

- A hormone secreted by the kidneys that causes the conversion of angiotensinogen in the blood into angiotensin.

Angiotensin

- A peptide hormone that constricts blood vessels, causes the retention of sodium and water, and produces thirst and a salt appetite.

Little Billy started eating salt. He had always liked plenty of salt on his food, but his craving finally got out of hand. His mother noticed that a carton of salt lasted only a few days, and one afternoon she caught Billy in the kitchen with the container of salt on the counter next to him, eating something out of his hand. It was salt, pure salt! She grabbed his hand and shook the salt out of it into the sink and then put the container on a shelf where Billy couldn’t reach it. Billy started crying and said, “Mommy, don’t take it away—I need that!”

The next morning she heard a crash in the kitchen and found Billy on the floor, an overturned chair next to him. Clearly, he was trying to get at the salt. “What’s wrong with you?” she cried. Billy sobbed and said, “Please, Mommy, I need some salt! I need it!” Bewildered but moved by his distress, she reached down the container and poured some salt in his hand, which he ate eagerly.

After consulting with the family physician, Billy’s parents decided to have him admitted to the hospital, where his bizarre craving could be investigated. Although Billy cried piteously that he needed salt, the hospital staff made sure that he received no more than a child normally needs. He tried several times to leave his room, presumably to try to find some salt, but he was brought back, and the door to his room was finally locked. Unfortunately, before definitive testing could be begun, Billy died.

The diagnosis of Billy’s craving came too late to help him. A disease process had caused his adrenal glands to stop secreting aldosterone, a steroid hormone that stimulates the kidneys to retain sodium. Without this hormone, excessive amounts of sodium are excreted by the kidneys, which causes the volume of the blood to fall. In Billy’s case the fall in blood volume that occurred when his access to salt was blocked led to a fatal loss of blood pressure. This unhappy story occurred several decades ago, and we can hope that physicians today would recognize an intense salt craving as a cardinal symptom of adrenal insufficiency.

Important Brain Structures

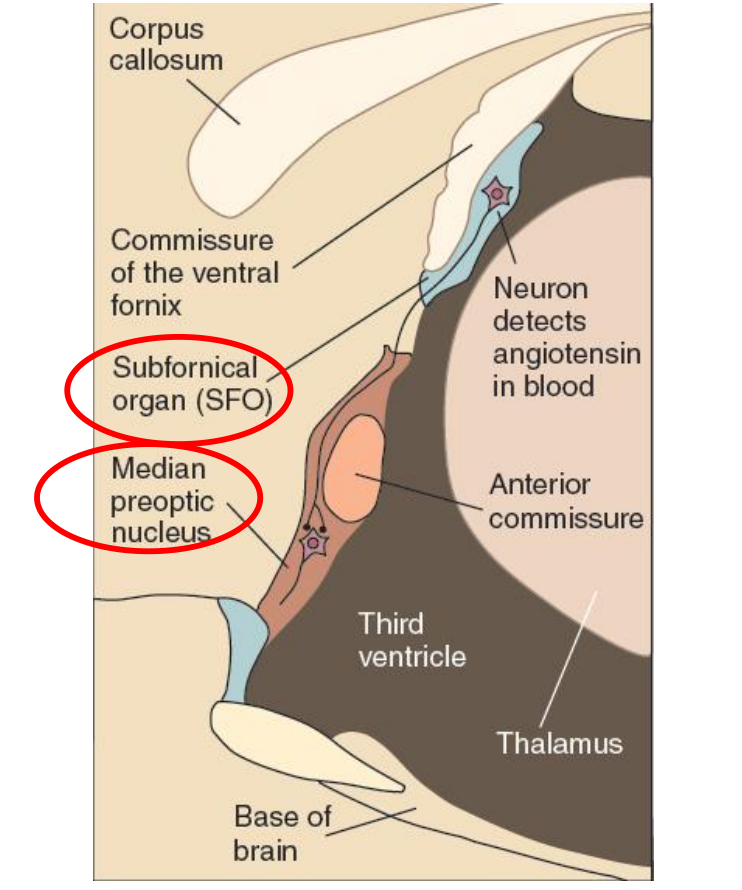

Angiotensin acts on neurons found in one of the organs of the brain located outside the blood–brain barrier, the subfornical organ (SFO).

This structure gets its name from its location, just below the commissure of the ventral fornix.

Neurons in the SFO send their axons to the median preoptic nucleus (not to be confused with the medial preoptic nucleus), a small nucleus wrapped around the front of the anterior commissure, a fiber bundle that connects the amygdala and anterior temporal lobe. Neurons in the median preoptic nucleus then communicate with the motor systems involved in drinking.

(1) The Subfornical Organ

The Subfornical Organ:

- This sagittal section of the rat diencephalon shows the location of the subfornical organ and its connection with the median preoptic nucleus.

- A small organ located in the confluence of the lateral ventricles, attached to the underside of the fornix; contains neurons that detect the presence of angiotensin in the blood and excite neural circuits that initiate drinking.

(2) Median preoptic nucleus

- A small nucleus situated around the front of the anterior commissure; plays a role in thirst stimulated by angiotensin.

c

c

三、Eating: Some Facts about Metabolism

Clearly, eating is one of the most important things we do, and it can also be one of the most pleasurable.

Much of what an animal learns to do is motivated by the constant struggle to obtain food; therefore, the need to ingest undoubtedly shaped the evolutionary development of our own species.

Control of eating is even more complicated than the control of drinking and sodium intake. We can achieve water balance by the intake of two ingredients: water and sodium chloride. When we eat, we must obtain adequate amounts of carbohydrates, fats, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals other than sodium. Therefore, our food-ingestive behaviors are more complex, as are the physiological mechanisms that control them.

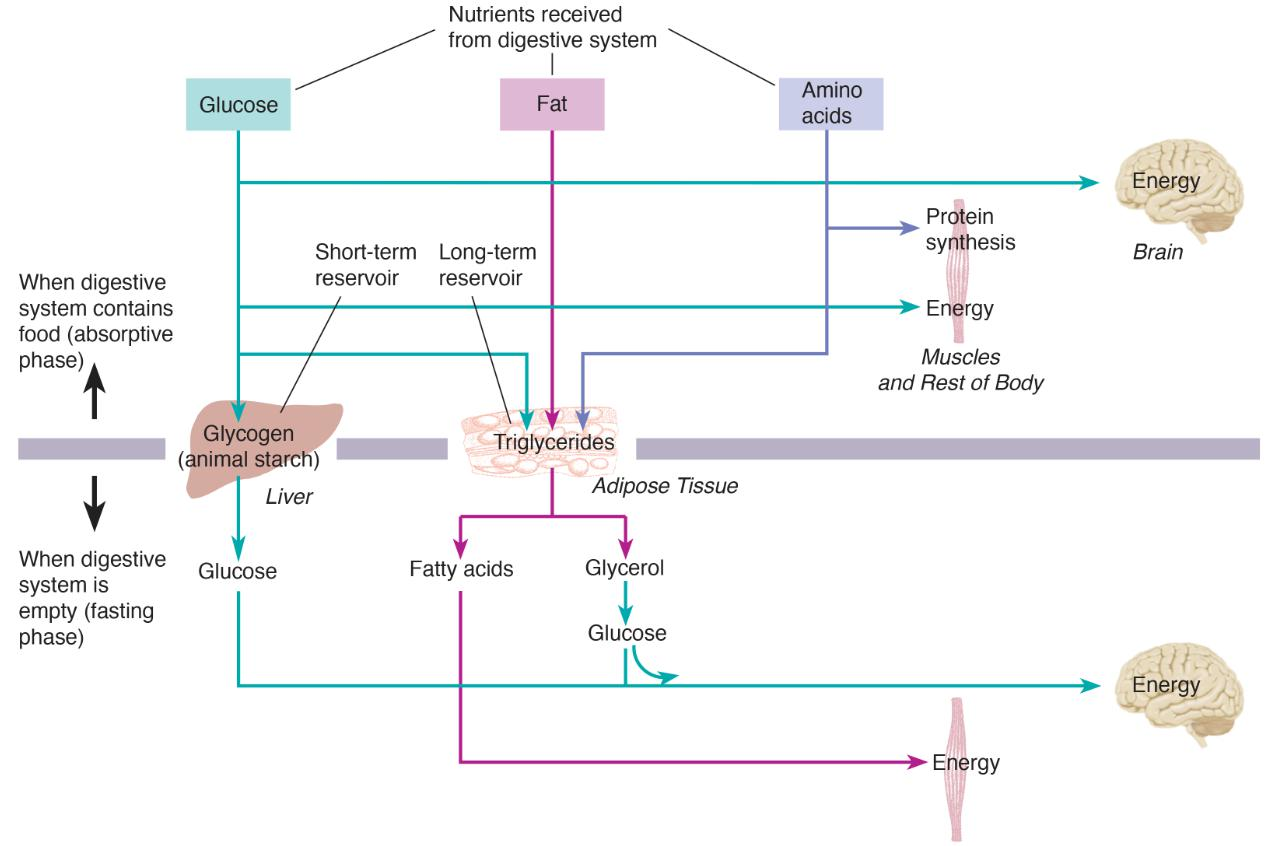

To stay alive, our cells must be supplied with fuel and oxygen. Obviously, fuel comes from the digestive tract, and its presence there is a result of eating. But the digestive tract is sometimes empty; in fact, most of us wake up in the morning in that condition. So there has to be a reservoir that stores nutrients to keep the body’s cells nourished when the gut is empty. Indeed, there are two reservoirs: one short-term and the other long-term. The short-term reservoir stores carbohydrates, and the long-term reservoir stores fats.

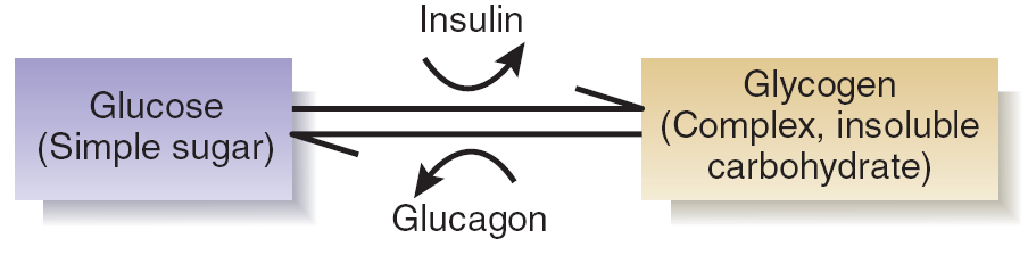

The short-term reservoir is located in the cells of the liver and the muscles. For simplicity we will consider only one of these locations: the liver. Cells in the liver convert glucose (a simple, soluble carbohydrate) into glycogen and store the glycogen. They are stimulated to do so by the presence of insulin , a peptide hormone produced by the pancreas.

Thus, when glucose and insulin are present in the blood, some of the glucose is used as a fuel, and some of it is stored as glycogen. Later, when all of the food has been absorbed from the digestive tract, the level of glucose in the blood begins to fall.

The fall in glucose is detected by cells in the pancreas and in the brain. The pancreas responds by stopping its secretion of insulin and starting to secrete a different peptide hormone: glucagon . The effect of glucagon is opposite that of insulin: It stimulates the conversion of glycogen into glucose.

Thus, the liver soaks up excess glucose and stores it as glycogen when plenty of glucose is available, and it releases glucose from its reservoir when the digestive tract becomes empty and the level of glucose in the blood begins to fall.

Effects of Insulin and Glucagon on Glucose and Glycogen

The carbohydrate reservoir in the liver is reserved primarily for the central nervous system. When you wake in the morning, your brain is being fed by your liver, which is in the process of converting glycogen to glucose and releasing it into the blood.

- The glucose reaches the CNS, where it is absorbed and metabolized by the neurons and the glia.

- This process can continue for a few hours, until all of the carbohydrate reservoir in the liver is used up. (The average liver holds approximately 300 calories of carbohydrate.)

- Usually, we eat some food before this reservoir gets depleted, which permits us to refill it. But if we do not eat, the CNS (and the rest of the body) must start living on the products of the long-term reservoir.

Our long-term reservoir consists of adipose tissue (fat tissue). This reservoir is filled with fats, or, more precisely, with triglycerides . Adipose tissue is found beneath the skin and in various locations in the abdominal cavity. It consists of cells that are capable of absorbing nutrients from the blood, converting them to triglycerides, and storing them. These cells can expand enormously in size; in fact, the primary physical difference between an obese person and a person of normal weight is the size of their fat cells, which is determined by the amount of triglycerides that these cells contain.

- The long-term fat reservoir is obviously what keeps us alive when we are fasting.

As we just saw, when we wake in the morning with an empty digestive tract, our brain is living on glucose released by the liver. But what about the other cells of the body? They are living on fatty acids, sparing the glucose for the brain.

When the digestive system is empty, there is an increase in the activity of the sympathetic axons that innervate adipose tissue, the pancreas, and the adrenal medulla. All three effects (direct neural stimulation, secretion of glucagon, and secretion of catecholamines) cause triglycerides in the long-term fat reservoir to be broken down into glycerol and fatty acids.

The fatty acids can be directly metabolized by cells in all of the body except the brain, which needs glucose. That leaves glycerol. The liver takes up glycerol and converts it to glucose. That glucose, too, is available to the brain….

Why the rest of the body’s cells treat the brain so kindly, letting it consume almost all the glucose that the liver releases from its carbohydrate reservoir and constructs from glycerol.

The answer is simple: Insulin has several other functions besides causing glucose to be converted to glycogen. One of these functions is controlling the entry of glucose into cells. To be taken into a cell, glucose must be transported there by glucose transporters—protein molecules that are situated in the membrane and are similar to those responsible for the reuptake of transmitter substances.

- Glucose transporters contain insulin receptors, which control their activity; only when insulin binds with these receptors can glucose be transported into the cell.

But the cells of the nervous system are an exception to this rule. Their glucose transporters do not contain insulin receptors; these cells can absorb glucose even when insulin is not present.

Fasting phase

- The phase of metabolism during which nutrients are not available from the digestive system; glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids are derived from glycogen, protein, and adipose tissue during this phase.

Absorptive phase

- The phase of metabolism during which nutrients are absorbed from the digestive system; glucose and amino acids constitute the principal source of energy for cells during this phase, and excess nutrients are stored in adipose tissue in the form of triglycerides.

Metabolic Pathways During the Fasting Phase and Absorptive Phase of Metabolism:

This figure reviews the metabolism that takes place while the digestive tract is empty, which physiologists refer to as the fasting phase of metabolism.

A fall in blood glucose level causes the pancreas to stop secreting insulin and to start secreting glucagon.

The absence of insulin means that most of the cells of the body can no longer use glucose; thus, all the glucose present in the blood is reserved for the central nervous system.

四、What Starts a Meal?

Regulation of body weight requires a balance between food intake and energy expenditure. If we ingest more calories than we burn, we will gain weight. Assuming that our energy expenditure is constant, we need two mechanisms to maintain a relatively constant body weight.

One mechanism must increase our motivation to eat if our long-term nutrient reservoir is becoming depleted, and another mechanism must restrain our food intake if we begin to take in more calories than we need.

Unfortunately, the first mechanism is more effective than the second one.

Signals from the Environment

In the past, starvation was a much greater threat to survival than overeating was. In fact, a tendency to overeat in times of plenty provided a reserve that could be drawn upon if food became scarce again. A feast-or-famine environment favored the evolution of mechanisms that were quick to detect losses from the long-term reservoir and provide a strong signal to seek and eat food. Natural selection for mechanisms that detected weight gain and suppressed overeating was much less significant.

We tend to eat when our stomach and upper intestine are empty. This emptiness provides a hunger signal—a message to our brain that indicates that we should begin to eat. The time it takes for food to leave our stomach would seem to encourage the establishment of a pattern of eating three meals a day.

Although an empty stomach is an important signal, many factors start a meal, including the sight of a plate of food, the smell of food cooking in the kitchen, the presence of other people sitting around the table, or the words “It’s time to eat!”

Signals from the Stomach

An empty stomach and upper intestine provide an important signal to the brain that it is time to start thinking about finding something to eat.

Recently, researchers discovered one of the ways this signal may be communicated to the brain.

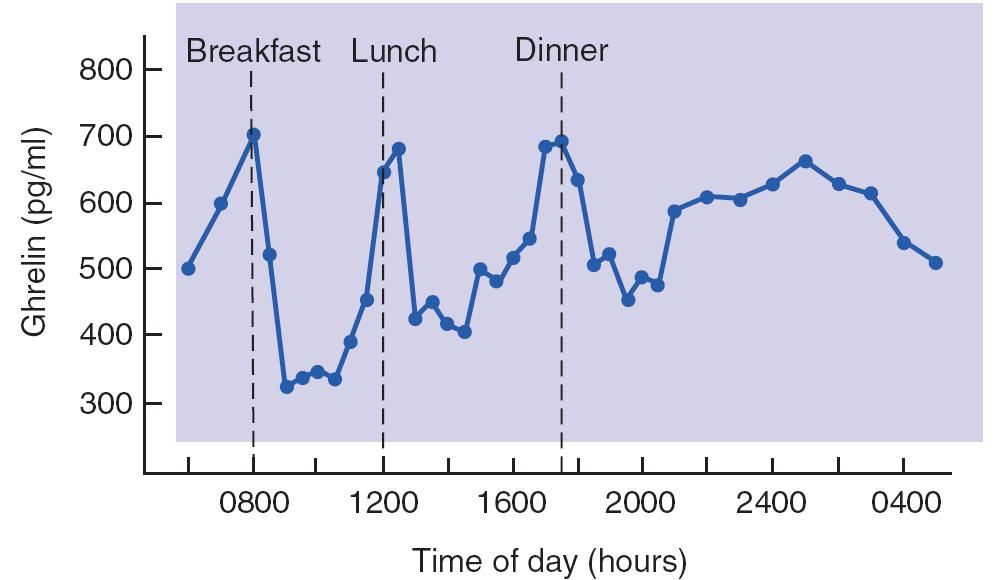

The gastrointestinal system (especially the stomach) releases a peptide hormone called ghrelin (生长激素释放激素、饥饿激素)(Kojima et al., 1999).

- Levels of Ghrelin in Human Blood Plasma

- The graph shows that a rise in the level of this peptide preceded each meal.

The blood levels of ghrelin increase with fasting and are reduced after a meal.

- In humans, blood levels of ghrelin increase shortly before each meal, which suggests that this peptide is involved in the initiation of a meal. Ghrelin is a potent stimulator of food intake, and it even stimulates thoughts about food.

Schmid et al. (2005) found that a single intravenous injection of ghrelin not only enhanced appetite in normal subjects, it also elicited vivid images of foods that the subjects liked to eat.

Subcutaneous injection or infusion of ghrelin into the cerebral ventricles of laboratory animals causes weight gain by increasing food intake and decreasing the metabolism of fats.

Although ghrelin is an important short-term hunger signal, it clearly cannot be the only one.

For example, people with successful gastric bypass surgery have almost negligible levels of ghrelin in the blood. Although they eat less and lose weight, they certainly do not stop eating.

In addition, mice with a targeted mutation against the ghrelin gene or the ghrelin receptor have normal food intake and body weight.

However, Zigman et al. (2005) found that this mutation protected mice from overeating and gaining weight when fed a tasty high-fat diet that induced obesity in normal mice. Thus, alternative mechanisms can stimulate feeding which, given the vital importance of food, is not surprising. In fact, one of the factors that complicates research on ingestive behavior is the presence of redundant systems.

Metabolic Signals

A fall in blood glucose level (a condition known as hypoglycemia) is a potent stimulus for hunger.

Hypoglycemia can be produced experimentally by giving an animal a large injection of insulin, which causes cells in the liver, muscles, and adipose tissue to take up glucose and store it away.

We can also deprive cells of glucose by injecting an animal with a drug that interferes with the metabolism of glucose.

Both of these treatments cause glucoprivation ; that is, they deprive cells of glucose. And glucoprivation, whatever its cause, stimulates eating.

Hunger can also be produced by causing lipoprivation —depriving cells of lipids. More precisely, they are deprived of the ability to metabolize fatty acids through injection of a drug that interferes with this process.

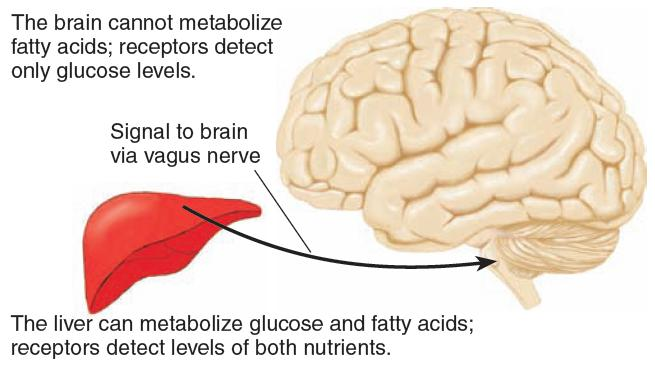

What is the nature of the detectors that monitor the level of metabolic fuels, and where are these detectors located?

The evidence that has been gathered so far indicates that there are two sets of detectors:

- one set located in the brain

- the other set located in the liver.

The figure shows the probable location of nutrient receptors responsible for hunger signals.:

The brain contains detectors that monitor the availability of glucose (its only fuel) inside the blood–brain barrier, and the liver contains detectors that monitor the availability of nutrients (glucose and fatty acids) outside the blood–brain barrier.

五、What Stops a Meal?

There are two primary sources of satiety signals—the signals that stop a meal.

Short-term satiety signals come from the immediate effects of eating a particular meal, which begin long before the food is digested. To search for these signals, we will follow the pathway traveled by ingested food: the stomach, the small intestine, and the liver. Each of these locations can potentially provide a signal to the brain that indicates that food has been ingested and is progressing on the way toward absorption.

Long-term satiety signals arise in the adipose tissue, which contains the long-term nutrient reservoir. These signals do not control the beginning and end of a particular meal, but they do, in the long run, control the intake of calories by modulating the sensitivity of brain mechanisms to the hunger and satiety signals that they receive

Gastric Factors

The stomach apparently contains receptors that can detect the presence of nutrients.

Deutsch and Gonzalez (1980) found that when they removed food from the stomach of a rat that had just eaten all it wanted, the animal would immediately eat just enough food to replace what had been removed— even if the experimenters replaced the food with a nonnutritive saline solution.

Obviously, the rats did not do so simply by measuring the volume of the food in their stomachs, because they were not fooled by the infusion of a saline solution. Of course, this study indicates only that the stomach contains nutrient receptors

Intestinal Factors

The intestines do contain nutrient detectors.

Studies with rats have shown that afferent axons arising from the duodenum are sensitive to the presence of glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids (Ritter et al., 1992). In fact, some of the chemoreceptors found in the duodenum are also found in the tongue. These axons may transmit a satiety signal to the brain.

Feinle, Grundy, and Read (1997) had people swallow an inflatable bag attached to the end of a thin, flexible tube. When the stomach and duodenum were empty, the subjects reported that they simply felt bloated when the bag was inflated, filling the stomach.

However, when fats or carbohydrates were infused into the duodenum while the bag was being inflated, the people reported sensations of fullness like those experienced after eating a meal.

After food reaches the stomach, it is mixed with hydrochloric acid and pepsin, an enzyme that breaks proteins into their constituent amino acids.

As digestion proceeds, food is gradually introduced from the stomach into the duodenum. There, the food is mixed with bile and pancreatic enzymes, which continue the digestive process. Bile breaks fats down into small particles so that they can be absorbed from the intestines.

The duodenum controls the rate of stomach emptying by secreting a peptide hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK,胆囊收缩素) . CCK causes the gallbladder (cholecyst) to contract, injecting bile into the duodenum.

CCK is secreted in response to the presence of fats, which are detected by receptors in the walls of the duodenum.

In addition to stimulating contraction of the gallbladder, CCK causes the pylorus to constrict and inhibits gastric contractions, thus keeping the stomach from giving the duodenum more food.

1. Some info about CCK (Cholecystokinin) interneuron

Cholecystokinin (CCK) interneurons are a subclass of interneurons found to be highly abundant throughout the neocortex and hippocampus.

A majority of CCK interneurons are densely innervate the cell soma, proximal dendrites, and axon initial segment of pyramidal cells.

CCK interneurons exert strong rapid feedforward inhibition onto pyramidal cells.

This powerful postsynaptic inhibition is also long-lasting in nature in accordance with their asynchronous GABA release.

Moreover, CCK interneurons express several neuromodulatory receptors, such as those for 5HT3a, nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and the endocannabinoid CB1 receptor, implicating them in behavioral state-dependent processing.

Obviously, the blood level of CCK is related to the amount of nutrients (particularly fats) that the duodenum receives from the stomach. Thus, this hormone could potentially provide a satiety signal to the brain, telling it that the duodenum was receiving food from the stomach.

Many studies have indeed found that injections of CCK suppress eating.

However, mice with a targeted mutation against the gene responsible for the production of CCK ate normal amounts of food and did not become obese.

CCK does not act directly on the brain; instead, it acts on receptors located in the junction between the stomach and the duodenum (Moran et al., 1989).

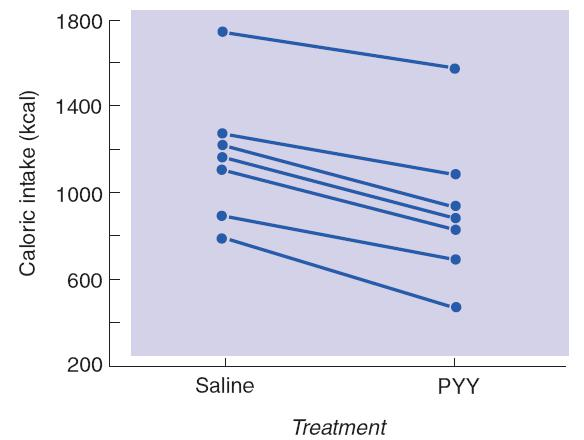

Investigators have discovered another chemical produced PYY by cells in the gastrointestinal tract that serves as an additional satiety signal.

PYY is released by the small intestine after a meal in amounts proportional to the calories that were just ingested (Pedersen-Bjergaard et al., 1996).

- Only nutrients caused PYY to be secreted; a large drink of water had no effect. Injections of PYY significantly decreased the size of meals eaten by members of several species, including rats and both lean and obese humans.

In addition, the amount of PYY released after a meal correlates positively with people’s ratings of satiety.

Effects of PYY on Hunger

- The graph shows the amount of food (in kilocalories) eaten at a buffet meal 30 minutes after people received a 90-minute intravenous infusion of saline or PYY. Data points from each subject are connected by straight lines.

Liver Factors

The absorptive phase of metabolism is accompanied by an increased level of insulin in the blood.

- Insulin permits organs other than the brain to metabolize glucose.

- Insulin promotes the entry of nutrients into fat cells where they are converted into triglycerides.

- Cells in the brain do not need insulin to metabolize glucose. Nevertheless, the brain contains insulin receptors. These insulin receptors detect insulin present in the blood, which tells the brain that the body is probably in the absorptive phase of metabolism. Thus, insulin may serve as a satiety signal.

1. Insulin

Insulin is a peptide and would not normally be admitted to the brain.

However, a transport mechanism delivers it through the blood–brain barrier, and it reaches neurons in the hypothalamus that are involved in regulation of hunger and satiety.

Infusion of insulin into the third ventricle inhibits eating and causes a loss of body weight.

In addition, Brüning et al. (2000) prepared a targeted mutation in mice that blocked the production of insulin receptors in the brain without affecting their production elsewhere in the body. The mice became obese, especially when they were fed a tasty, high-fat diet, which would be expected if one of the factors that promotes satiety was absent.

Long-Term Satiety: Signals from Adipose Tissue

Short-term satiety factors: those arising from a single meal.

In most people, body weight appears to be regulated over a long-term basis.

If an animal is force-fed so that it becomes fatter than normal, it will reduce its food intake once it is permitted to choose how much to eat.Similar studies have shown that an animal will adjust its food intake appropriately if it is given a high-calorie or low-calorie diet.

And if an animal is put on a diet that reduces its body weight, short-term satiety factors become much less effective.

Thus, signals arising from the long-term nutrient reservoir may alter the brain’s sensitivity to hunger signals or short-term satiety signals.

What exactly is the system variable that permits the body weight of most organisms to remain relatively stable?

The basic difference between obese and nonobese people is the amount of fat stored in their adipose tissue. Perhaps fat tissue provides a signal to the brain that indicates how much of it there is.

The discovery of a long-term satiety signal from fat tissue came after years of study with a strain of genetically obese mice.

- The ob mouse has a low metabolism, overeats, and gets exceedingly fat. It also develops diabetes in adulthood, just as many obese people do.

- A particular gene, called OB, normally produces a peptide hormone that has been given the name leptin(瘦素) (from the Greek word leptos, “thin”). Leptin is normally secreted by well-nourished fat cells. Because of a genetic mutation, the fat cells of ob mice are unable to produce leptin.

Effects of Leptin on Obesity in Mice:

- The ob (obese) strain mouse on the left is untreated; the one on the right received daily injections of leptin.

Leptin has profound effects on metabolism and eating, acting as an antiobesity hormone. If ob mice are given daily injections of leptin, their metabolic rate increases, their body temperature rises, they become more active, and they eat less. As a result, their weight returns to normal.

六、Brain Mechanisms

Although hunger and satiety signals originate in the digestive system and in the body’s nutrient reservoirs, the target of these signals is the brain.

This section looks at some of the research on :

- the brain mechanisms that control food intake and metabolism

Brain Stem

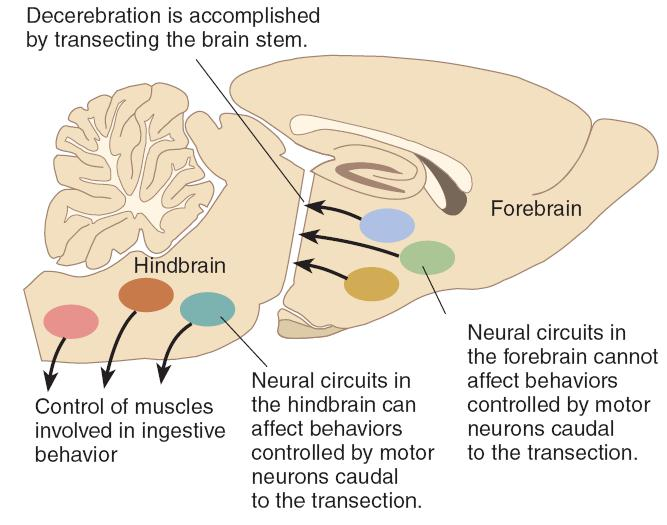

Ingestive behaviors are phylogenetically ancient; obviously, all our ancestors ate and drank, or else they died. Therefore, we should expect that the basic ingestive behaviors of chewing and swallowing are programmed by phylogenetically ancient brain circuits.

Indeed, studies have shown that these behaviors can be performed by decerebrate rats, whose brains were transected between the diencephalon and the midbrain.

Decerebration disconnects the motor neurons of the brain stem and spinal cord from the neural circuits of the cerebral hemispheres (such as the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia) that normally control them. The only behaviors that decerebrate animals can display are those that are directly controlled by neural circuits located within the brain stem.

1. Decerebration

Decerebration 大脑切除术

- A surgical procedure that severs the brain stem, disconnecting the hindbrain from the forebrain. (将后脑和前脑分开)

- The operation disconnects the forebrain from the hindbrain so that the muscles involved in ingestive behavior are controlled solely by hindbrain mechanisms.

Decerebrate rats cannot approach and eat food;

the experimenters must place food, in liquid form, into their mouths.

Decerebrate rats can distinguish between different tastes;

they drink and swallow sweet or slightly salty liquids and spit out bitter ones. They even respond to hunger and satiety signals.

They drink more sucrose after having been deprived of food for 24 hours, and they drink less of it if some sucrose is first injected directly into their stomachs. They also eat in response to glucoprivation.

These studies indicate that the brain stem contains neural circuits that can detect hunger and satiety signals and control at least some aspects of food intake.

- wo regions of the medulla, the area postrema and the nucleus of the solitary tract (henceforth referred to as the AP/NST), receive taste information from the tongue and a variety of sensory information from the internal organs, including signals from detectors in the stomach, duodenum, and liver.

In addition, this region contains a set of detectors that are sensitive to the brain’s own fuel: glucose. All this information is transmitted to regions of the forebrain that are more directly involved in control of eating and metabolism.

Evidence indicates that events that produce hunger increase the activity of neurons in the AP/NST. In addition, lesions of this region abolish both glucoprivic and lipoprivic feeding.

Hypothalamus

Discoveries made in the 1940s and 1950s focused the attention of researchers interested in ingestive behavior on two regions of the hypothalamus: the lateral area and the ventromedial area.

For many years investigators believed that these two regions controlled hunger and satiety, respectively; one was the accelerator, and the other was the brake.

The basic findings were these: After the lateral hypothalamus was destroyed, animals stopped eating or drinking. Electrical stimulation of the same region would produce eating, drinking, or both behaviors.

Conversely, lesions of the ventromedial hypothalamus produced overeating that led to gross obesity, whereas electrical stimulation suppressed eating.

1. role of hunger

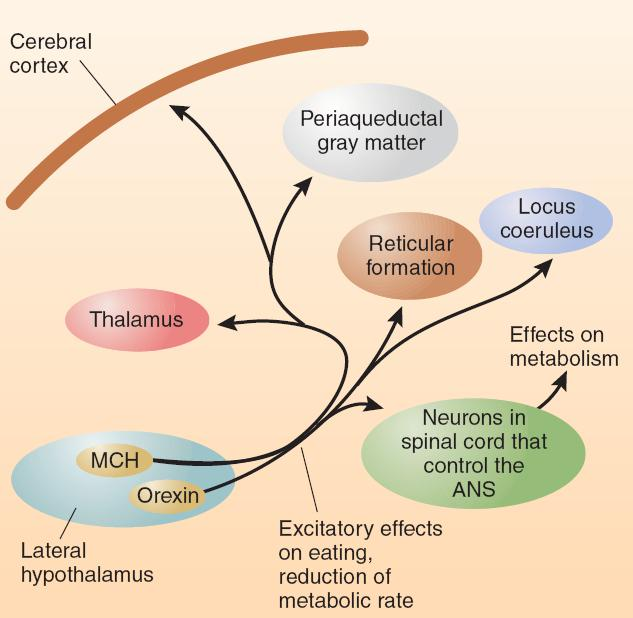

Research has discovered several peptides produced by neurons in the hypothalamus that play a special role in the control of feeding and metabolism (Arora and Anubhuti, 2006).

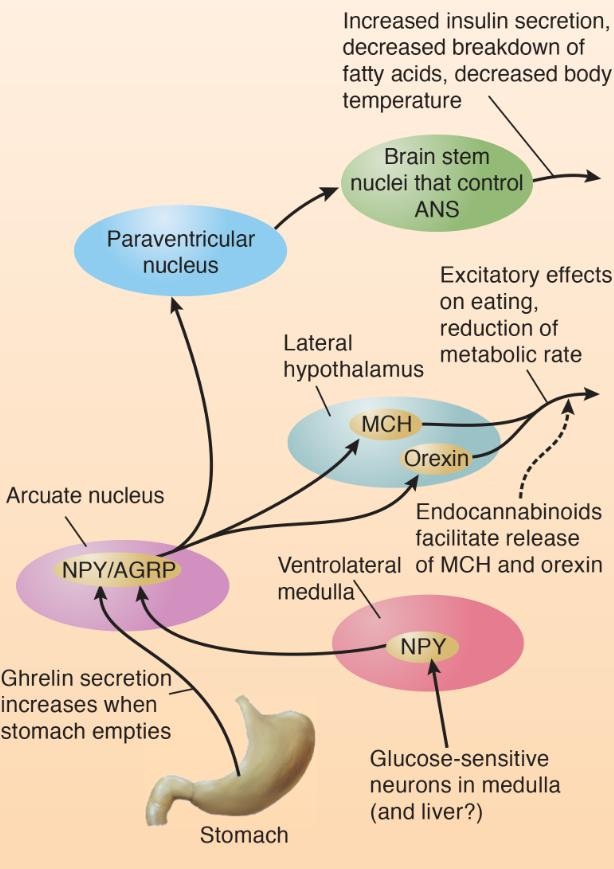

Two of these peptides, melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH,黑色素凝集素) and orexin (also called hypocretin) , produced by neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, stimulate hunger/appetite and decrease metabolic rate, thus increasing and preserving the body’s energy stores.

- Degeneration of neurons that secrete orexin is responsible for narcolepsy. Evidence reviewed there indicates that it plays a role in keeping the brain’s sleep–waking switch in the “waking” position.

Researchers refer to MCH and orexin as orexigens(食欲诱导化学物质), “appetite- inducing chemicals.” Injections of either of these peptides into the lateral ventricles or various regions of the brain induce eating.

- If rats are deprived of food, production of MCH and orexin in the lateral hypothalamus increases.

Of these two orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, MCH appears to play the more important role in stimulating feeding.

Mice with a targeted mutation against the MCH gene or those that receive injections of an MCH receptor antagonist eat less than normal mice and are consequently underweight.

In addition, genetically engineered mice with increased production of MCH in the hypothalamus overeat and gain weight.

Feeding Circuits in the Brain:

- This schematic diagram shows connections of the MCH neurons and orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus.

The axons of MCH and orexin neurons travel to a variety of brain structures that are known to be involved in motivation and movement, including the neocortex, periaqueductal gray matter, reticular formation, thalamus, and locus coeruleus.

These neurons also have connections with neurons in the spinal cord that control the autonomic nervous system, which explains how they can affect the body’s metabolic rate.

As we saw earlier, hunger signals caused by an empty stomach or by glucoprivation or lipoprivation arise from detectors in the abdominal cavity and brain stem.

How do these signals activate the MCH and orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus? Part of the pathway involves a system of neurons that secrete a neurotransmitter called neuropeptide Y (NPY) , an extremely potent stimulator of food intake. Infusion of NPY into the hypothalamus produces ravenous, almost frantic eating.

Neuropeptide Y (NPY)

A peptide neurotransmitter found in a system of neurons of the arcuate nucleus that stimulate feeding, insulin and glucocorticoid secretion, decrease the breakdown of triglycerides, and decrease body temperature.

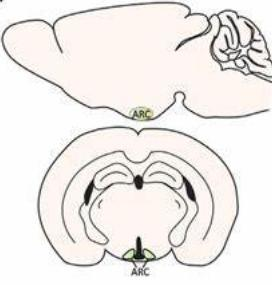

Arcuate nucleus

A nucleus in the base of the hypothalamus that controls secretions of the anterior pituitary gland; contains NPY-secreting neurons involved in feeding and control of metabolism.

A genetic manipulation that increased the production of NPY in the hypothalamus increased food intake in rats.

In contrast, a manipulation that decreased its production reduced eating, obesity, and diabetes of members of a strain of rats that had been selectively bred to overeat and become obese.

Neurons that secrete NPY are affected by hunger and satiety signals.

Hypothalamic levels of NPY are increased by food deprivation and lowered by eating.

Glucose-sensitive neurons in the medulla activate NPY neurons.

In normal mice, glucoprivation caused an increase in NPY production.

Mice with a targeted mutation against the gene for NPY showed a feeding deficit in response to glucoprivation.

(1) The role ghrelin in this part

As we saw earlier, ghrelin, released by the stomach, provides a potent hunger signal to the brain.

- Rats with a targeted mutation that prevents ghrelin receptors from being produced in the hypothalamus ate less and gained weight more slowly than normal rats did. Evidence indicates that the ghrelin receptors that stimulate eating are located on NPY neurons.

Thus, two important hunger signals—glucoprivation and ghrelin—activate the orexigenic NPY neurons.

(2) Through what neural circuits does NPY exert its effects on eating and metabolic functions?

NPY neurons of the arcuate nucleus send a projection directly to the MCH and orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus that stimulate eating.

In addition, NPY neurons send a projection of axons to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) —a region of the hypothalamus where infusions of NPY affect metabolic functions.

The terminals of hypothalamic NPY neurons release another orexigenic peptide in addition to neuropeptide Y: agouti-related peptide , otherwise known as AGRP. The two hormones appear to act together. AGRP, like NPY, is a potent and extremely long-lasting orexigen.

Infusion of a very small amount of this AGRP into the third ventricle of rats produces an increase in food intake that lasts for six days.

(3) The Endocannabinoids 内源性大麻素

One other category of orexigenic compounds: the endocannabinoids.

- One of the effects of the THC contained in marijuana is an increase in appetite—especially for highly palatable foods.

The endocannabinoids, whose actions are mimicked by THC, stimulate eating, apparently by increasing the release of MCH and orexin.

Levels of endocannabinoids are highest during fasting and lowest during feeding. A genetic mutation that disrupts the production of the enzyme that destroys the endocannabinoids after they have been released causes overweight and obesity. Cannabinoid agonists have been used to increase the appetite of cancer patients, and until adverse side effects were discovered, cannabinoid antagonists were used as an aid to weight reduction.

Action of Hunger Signals on Feeding Circuits in the Brain:

- The diagram shows connections of the NPY neurons of the arcuate nucleus.

In summary, activity of MCH and orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus increases food intake and decreases metabolic rate.

These neurons are activated by NPY/AGRP-secreting neurons of the arcuate nucleus, which also project to the paraventricular nucleus, which plays a role in control of insulin secretion and metabolism.

The endocannabinoids stimulate appetite by increasing the release of MCH and orexin.

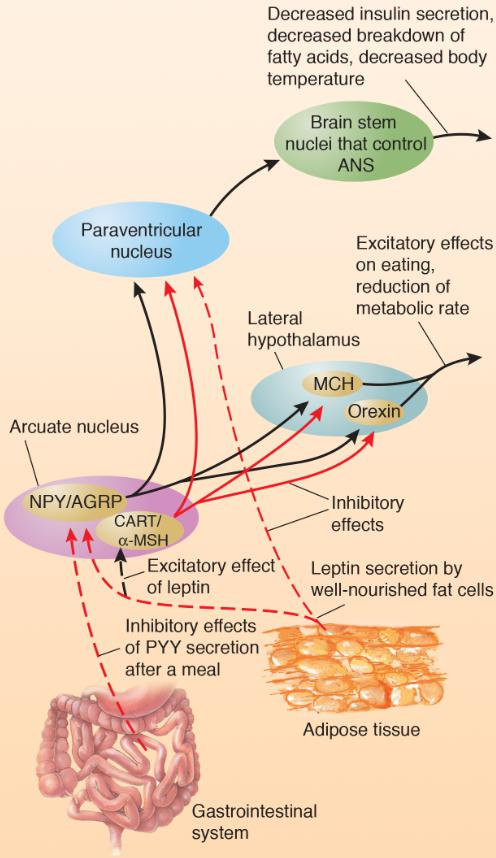

2. role of satiety

Leptin, a hormone secreted by well-fed adipose tissue, suppresses eating and raises the animal’s metabolic rate. The interactions of this long-term satiety signal with neural circuits involved in hunger are now being discovered.

- Leptin produces its behavioral and metabolic effects by binding with receptors in the brain—in particular, on neurons that secrete the orexigenic peptides NPY and AGRP.

- Activation of leptin receptors on NPY/AGRP-secreting neurons in the arcuate nucleus has an inhibitory effect on these neurons.

Leptin appears to suppress animals’ sensitivity to both olfactory and gustatory stimuli associated with food.

Getchell et al. (2006) found that ob mice, who lack the leptin gene, found buried food much faster than normal mice did. An injection of leptin into the mutant mice increased their time to find food. In addition, Kawai et al. (2000) found that leptin decreased the sensitivity of gustatory sweet receptors to the taste of sucrose and saccharine.

The arcuate nucleus contains two other systems of peptide-secreting neurons, both of which serve as anorexigens (“appetite-suppressing chemicals”).

Douglass, McKinzie, and Couceyro (1995) discovered a peptide that is now called CART (for cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript).

When cocaine or amphetamine is administered to an animal, levels of this peptide increase, which may have something to do with the fact that these drugs suppress appetite.

CART neurons appear to play an important role in satiety. If animals are deprived of food, levels of CART decrease. Injection of CART into their cerebral ventricles inhibits feeding, including the feeding stimulated by NPY, whereas infusion of a CART antibody, which destroys molecules of CART, increases feeding.

A second anorexigen, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) , is also released by CART neurons. This peptide binds with the receptor and inhibits feeding.

CART/α-MSH neurons are activated by leptin, and NPY/AGRP neurons are inhibited by leptin.

PYY, released by the gastrointestinal tract just after a meal, inhibits orexigenic NPY/AGRP neurons.

Leptin inhibits NPY/AGRP neurons, which suppress the feeding that these peptides stimulate and prevent the decrease in metabolic rate that they provoke.

Leptin activates CART/α-MSH neurons, which then inhibit MCH and orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus and prevent their stimulatory effect on appetite.

- High levels of leptin stimulate the release of the anorexigens CART and α-MSH and inhibit the release of the orexigens NPY and AGRP.

- Low levels of leptin have just the opposite effects: the anorexigenic CART/α-MSH neurons are not activated and the orexigenic NPY/AGRP neurons are not inhibited.

Action of Satiety Signals on Hypothalamic Neurons Involved in Control of Hunger and Satiety:

Neuropeptides and Peripheral Peptides Involved in Control of Food Intake and Metabolism

| Name | Where Produced | Site of Actions | Physiological or Behavioral Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin | Fat tissue | Inhibits NPY/AGRP neurons; excites CART/α-MSH neurons | Suppression of eating, increased metabolic rate |

| Insulin | Pancreas | Similar to leptin | Similar to leptin |

| Ghrelin | Gastrointestinal system | Activates NPY/AGRP neurons | Eating |

| Cholecystokinin (CCK) | Duodenum | Neurons in pylorus | Suppression of eating |

| Peptide YY |

Gastrointestinal system | Inhibits NPY/AGRP neurons | Suppression of eating |

| Name | Location of Cell Bodies | Location of Terminals | Interaction with Other Peptides | Physiological or Behavioral Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin-concentratinghormone (MCH) | Lateral hypothalamus | Neocortex, periaqueductal gray matter, reticular formation, thalamus, locus coeruleus, neurons in spinal cord that control the sympathetic nervous system | Activated by NPY/AGRP; inhibited by leptin and CART/α-MSH | Eating, decreased metabolic rate |

| Orexin | Lateral hypothalamus | Similar to those of MCH neurons | Activated by NPY/AGRP;inhibited by leptin andCART/α-MSH | Eating, decreased metabolic rate |

| Neuropeptide Y (NPY) | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus | Paraventricular nucleus, MCH and orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus | Activated by ghrelin;inhibited by leptin | Eating, decreased metabolic rate |

| Agouti-related protein (AGRP) | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus (colocalized with NPY) | Same regions as NPY neurons | Inhibited by leptin | Eating, decreased metabolic rate; acts as antagonist atMC4 receptors |

| Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript(CART) | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus | Paraventricular nucleus, lateral hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray matter, neurons in spinalcord that control the sympathetic nervous system | Activated by leptin | Suppression of eating, increased metabolic rate |

| α-Melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus(colocalized withCART) | Same regions as CART neurons | Activated by leptin | Suppression of eating, increased metabolic rate; actsas agonist at MC4 receptors |

七、Obesity

Obesity is a widespread problem that can have serious medical consequences.

In the United States, approximately 67 percent of men and 62 percent of women are overweight, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of over 25. In the past twenty years, the incidence of obesity, defined as a BMI of over 30, has doubled in the population as a whole, and has tripled for adolescents.

Obesity is also increasing in developing countries as household incomes rise. For example, over a ten-year period, the incidence of obesity in young urban children in China increased by a factor of eight (Ogden, Carroll, and Flegal, 2003; Zorrilla et al., 2006).

The known health hazards of obesity include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, and some forms of cancer. One hundred years ago, type 2 diabetes was almost never seen in people before the age of 40. However, because of the increased incidence of obesity in children, this disorder is now seen even in 10-year-old children.

Possible Causes

Genetic differences—and their effects on development of the endocrine system and brain mechanisms that control food intake and metabolism—appear to be responsible for the overwhelming majority of cases of extreme obesity.

But as we just saw, the problem of obesity and type 2 diabetes has been growing over recent years. Clearly, changes in the gene pool cannot account for this increase; instead, we must look to environmental causes that have produced changes in people’s behavior (availability of cheap, tasty, calorie-rich food and decreased levels of exercise).

Just as cars differ in their fuel efficiency, so do living organisms, and hereditary factors can affect the level of efficiency.

People differ in this form of efficiency too. Those with an efficient metabolism have calories left over to deposit in the long-term nutrient reservoir; thus, they have difficulty keeping this reservoir from growing. Researchers have referred to this condition as a “thrifty phenotype.”

In contrast, people with an inefficient metabolism (a “spendthrift phenotype”) can eat large meals without getting fat.

A fuel-efficient automobile is desirable, but a fuel-efficient body runs the risk of becoming obese—at least in an environment where food is cheap and plentiful.

Genes that promote an efficient metabolism are of benefit to people who must work hard for their calories but that these same genes turn into a liability when people live in an environment where the physical demands are low and high-calorie food is cheap and plentiful.

Treatment

As we saw earlier, study of the ob mouse led to the discovery of leptin, the hormone secreted by well-nourished adipose tissue. So far, researchers have found several cases of familial obesity caused by the absence of leptin, produced by the mutation of the gene responsible for its production or the production of the leptin receptor (Farooqi and O’Rahilly, 2005). Treatment of leptin-deficient people with injections of leptin has dramatic effects on the people’s body weights.

Hereditary Leptin Deficiency :

- The photographs show three patients with hereditary leptin deficiency before (a) and after (b) treatment with leptin for eighteen months. The faces of the patients are obscured for privacy. Two normal-weight nurses are shown for comparison purposes.

Unfortunately, leptin has no effect on people who lack leptin receptors. In any case, mutations of the genes for leptin or leptin receptors are very rare, so they do not explain the vast majority of cases of obesity. With the exception of these rare cases, leptin has not proved to provide a useful treatment for obesity. Indeed, obese people already have elevated blood levels of leptin, and additional leptin has no effect on their food intake or body weight. In other words, obese people show leptin resistance.

Leptin has not proved to provide a useful treatment for obesity. Indeed, obese people already have elevated blood levels of leptin, and additional leptin has no effect on their food intake or body weight.

People with a thrifty metabolism should show resistance to a high level of leptin, which would permit weight gain in times of plenty. In contrast, people with a spendthrift metabolism should not show leptin resistance and should eat less as their level of leptin rises.

Obesity is extremely difficult to treat.

Many programs help people to lose weight initially, but then the weight is quickly regained.

Whatever the cause of obesity, the metabolic fact of life is this:

- If calories in exceed calories out, then body fat will increase.

Because it is difficult to increase the “calories out” side of the equation enough to bring an obese person’s weight back to normal, most treatments for obesity attempt to reduce the “calories in.”

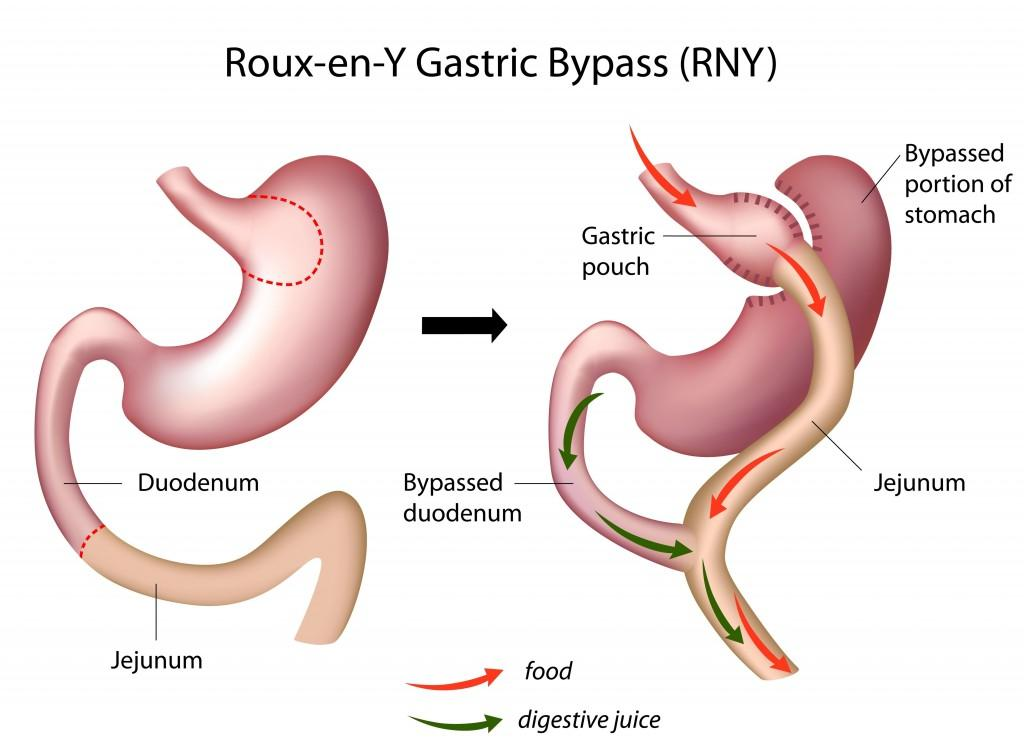

Bariatric surgery are designed to reduce the amount of food that can be eaten during a meal or interfere with absorption of calories from the intestines. Bariatric surgery has been aimed at the stomach, the small intestine, or both.

Difference between Bariatric surgery and liposuction

Liposuction is a cosmetic procedure intended to remove existing fat, but does not address the issues causing the patient’s weight gain. While you may initially lose weight or inches with liposuction it is not a permanent weight loss solution. Liposuction is more commonly recommended for individuals who are not struggling with obesity, but rather have areas of stubborn fat that just won’t melt away with diet and exercise.

Bariatric surgeries such as Gastric Sleeve, Gastric Bypass and LAP-BAND®, on the other hand, are all intended to address the cause of excess fat, rather than simply removing fat. Bariatric surgery can achieve long-term weight loss and is the best option for patients with a BMI of 30 or over.

The most effective form of bariatric surgery is a special form of gastric bypass called the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or RYGB.

The jejunum (the second part of the small intestine, immediately “downstream” from the duodenum) is cut, and the upper end is attached to the stomach pouch.

Digestive enzymes that are secreted into the duodenum pass through the upper intestine and meet up with the meal that has just been received from the stomach pouch.

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) Surgery:

- This procedure almost totally suppresses the secretion of ghrelin.

The RYGB procedure works well, although it often causes an iron and vitamin B12 deficiency, which may be controlled by increased intake of these substances.

In the United States alone, approximately 200,000 bariatric surgeries are performed each year. Brolin (2002) reported that the average postsurgical loss of excessive weight of obese patients was 65–75%, or about 35% of their initial weight.

Even patients who sustained smaller weight losses showed improved health, including reductions in hypertension and diabetes. A meta-analysis of 147 studies by Maggard et al. (2005) reported an average weight loss of 43.5 kg one year after RYGB surgery and 41.5 kg after three years.

Although the biological response to starvation is very strong—and is seen in obese people who are successfully losing weight—RYGB surgery does not induce these changes. Instead, after surgery people report that they feel less hungry and their level of exercise increases.

As Berthoud and his colleagues note, these results are “almost too good to be true.” However, like other forms of major surgery, adverse outcomes (including death) occasionally occur, but the rate of complications is lowest for surgeons with a higher than average experience performing the procedures (Smith et al., 2010).

One important reason for the success of the RYGB procedure appears to be that it disrupts the secretion of ghrelin.

The procedure also increases blood levels of PYY.

- Both of these changes would be expected to decrease food intake: A decrease in ghrelin should reduce hunger, and an increase in PYY should increase satiety.

A plausible explanation for the decreased secretion of ghrelin could be disruption of communication between the upper intestine and the stomach—as you will recall, although ghrelin is secreted by the stomach, the upper intestine controls this secretion.

Presumably, because the surgery decreases the speed at which food moves through the small intestine, more PYY is secreted.

Suzuki et al. (2005) found that rats that sustained a RYGB procedure ate less, lost weight, and showed decreased ghrelin levels and increased PYY levels.

Even normal rats continue to gain weight when they are housed in a cage with food always available, but the obesity surgery suppressed weight gain in both strains of animals.

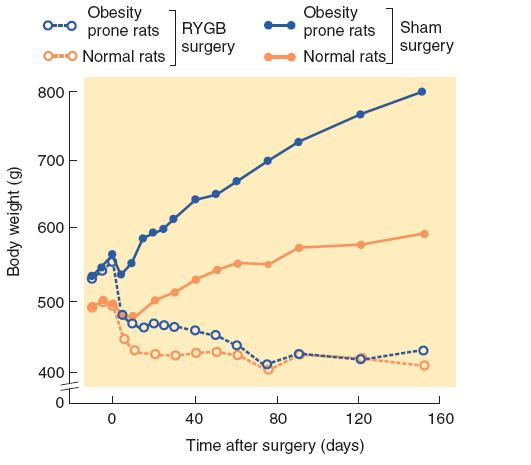

Effect of RYGB Surgery in Rats

- Rats genetically selected for development of obesity decreased their food intake and lost weight after receiving RYGB surgery. Their weight eventually reached that of normal rats that received the same operation.

A less drastic form of therapy for obesity—exercise—has significant benefits.

Decreased physical activity is an important cause of the increased number of overweight people. Exercise burns off calories, of course, but it also appears to have beneficial effects on metabolic rate.

Of course, if it were easy to convince people to commit to an exercise program, the incidence of obesity would be considerably lower than it is.

Another type of therapy for obesity—drug treatment—is the subject of active research programs by the pharmaceutical industry.

There are three possible ways in which drugs could help people lose weight:

- reduce the amount of food they eat

- prevent some of the food they eat from being digested

- increase their metabolic rate (that is, provide them with a “spendthrift phenotype”).

Unfortunately, a drug that successfully decreases eating by any of these means without producing unacceptable side effects has not yet been brought to the market.

Some serotonergic agonists suppress eating. These drugs can be of benefit in weight-loss programs.

However, one of the drugs most commonly used for this purpose, fenfluramine, was found to have hazardous side effects, including pulmonary hypertension and damage to the valves of the heart, so the drug was withdrawn from the market in the United States (Blundell and Halford, 1998). Fenfluramine acts by stimulating the release of 5-HT.

Another drug, sibutramine, has similar therapeutic effects on eating, but a study of people who were taking the drug found increased incidence of heart attacks and strokes, so this drug, too, was withdrawn from the market.

Another drug, orlistat, interferes with the absorption of fats by the small intestine. As a result, some of the fat in the person’s diet passes through the digestive system and is excreted with the feces. Possible side effects include leakage of undigested fat from the anus. (That sounds unpleasant!)

Marijuana often elicits a craving for highly palatable foods led to the discovery that the endocannabinoids have an orexigenic effect.

The drug rimonabant, which blocks CB1 cannabinoid receptors, was found to suppress appetite, produce a significant weight loss, lower blood levels of triglycerides and insulin, and increase blood levels of HDL (“good” cholesterol), with apparently minimal adverse side effects. However, use of rimonabant was subsequently found to be associated with depressive mood disorders, anxiety, and increased suicide risk, so it is no longer on the market as an antiobesity treatment.

Rimonabant has also been shown to help people stop smoking. Although the drug is not approved for this purpose either, its efficacy suggests that the craving for nicotine, like the craving for food, involves the release of endocannabinoids in the brain.

If we learn more about the physiology of hunger signals, satiety signals, and the reinforcement provided by eating, we may be able to develop safe and effective drugs that attenuate the signals that encourage us to eat and strengthen those that encourage us to stop eating.

八、Anorexia Nervosa/Bulimia Nervosa

Anorexia Nervosa (神经性厌食症) or Anorexia is a psychological and potentially life-threatening eating disorder characterized by abnormally low body weight, an intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted perception of weight.

Another eating disorder, bulimia nervosa(神经性贪食症) , is characterized by a loss of control of food intake. People with bulimia nervosa periodically gorge themselves with food, especially dessert or snack food and especially in the afternoon or evening. These binges are usually followed by self-induced vomiting or the use of laxatives, along with feelings of depression and guilt.

- Episodes of bulimia are seen in some patients with anorexia nervosa.

The incidence of anorexia nervosa is estimated at 0.5–2%; that of bulimia nervosa at 1–3%. Women are 10-20 times more likely than men to develop anorexia nervosa and approximately 10 times more likely to develop. bulimia nervosa.

1. Anorexia nervosa 神经性厌食症

A disorder that most frequently afflicts young women; exaggerated concern with being overweight that leads to excessive dieting and often compulsive exercising; can lead to starvation.

2. Bulimia nervosa 神经性贪食症

Bouts of excessive hunger and eating, often followed by forced vomiting or purging with laxatives; sometimes seen in people with anorexia nervosa.

Possible Causes

Anorexia is a serious disorder.

5 -10% die of complications of the disease or of suicide.

The literal meaning of the word anorexia suggests a loss of appetite, but people with this disorder are usually interested in—even preoccupied with—food. They may enjoy preparing meals for others to consume, collect recipes, and even hoard food that they do not eat.

Anorexics express an intense fear of becoming obese, which continues even if they become dangerously thin.

Many anorexics exercise by cycling, running, or almost constant walking and pacing.

Evidence suggests just the opposite: that the symptoms of eating disorders are actually symptoms of starvation.

A famous study carried out at the University of Minnesota by Ancel Keys and his colleagues (Keys et al., 1950) recruited 36 physically and psychologically healthy young men to observe the effects of semistarvation.

For six months, the men ate approximately 50% of what they had been eating previously, and as a result lost approximately 25% of their original body weight.

As the volunteers lost weight, they began displaying disturbing symptoms, including preoccupation with food and eating, ritualistic eating, erratic mood, impaired cognitive performance, and physiological changes such as decreased body temperature.

- They began hoarding food and nonfood objects and were unable to explain (even to themselves) why they bothered to accumulate objects that they had no use for.

The obsessions with food and weight loss and the compulsive rituals that people with anorexia nervosa develop suggest a possible linkage with obsessive-compulsive disorder. 、

- However, the fact that these obsessions and compulsions were seen in the subjects of the Minnesota study—none of whom showed these symptoms previously—suggests that they are effects rather than causes of the eating disorder.

Both anorexia and semistarvation include symptoms such as mood swings, depression, and insomnia. Even hair loss is seen in both conditions. The suicide rate in patients with anorexia is higher than that of the rest of the population (Pompili et al., 2004).

None of the volunteers in the Minnesota study committed suicide, but one cut off three of his fingers. This volunteer said, “I have been more depressed than ever in my life. . .”

Excessive exercising is a prominent symptom of anorexia (Zandian et al., 2007).

In fact, many fitness instructors recognized that some of their clients may have had an eating disorder and expressed concern about the ethical or liability issues in relation to permitting such clients to participate in their classes or facilities.

Studies with animals suggest that the increased activity may actually be a result of the fasting.

When rats are allowed access to food for one hour each day, they will spend more and more time running in a wheel if one is available and will lose weight and eventually die of emaciation (Smith, 1989).

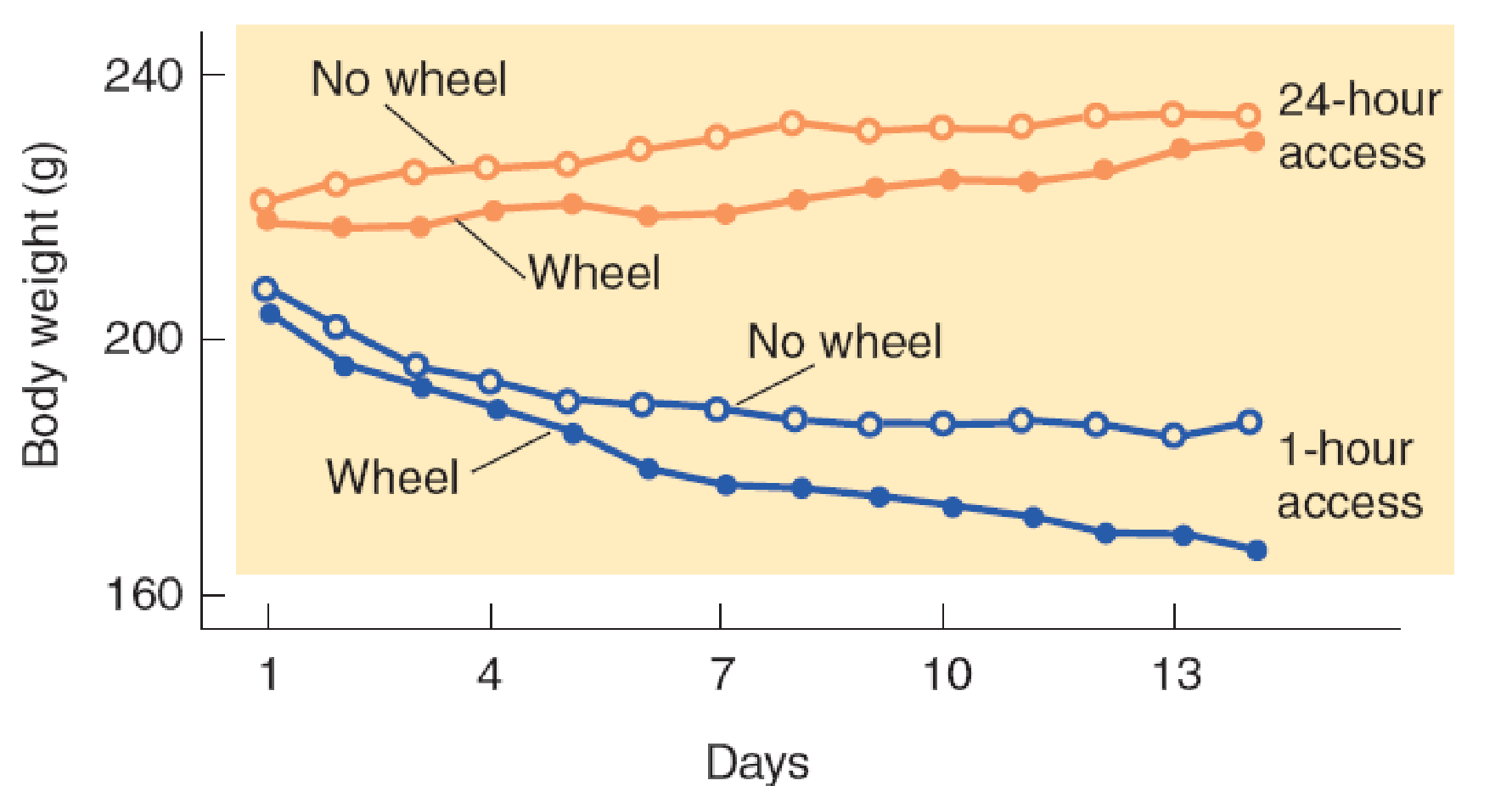

Activity, Food Restriction, and Weight Loss

Nergårdh et al. (2007) placed rats in individual cages. Some of the cages were equipped with running wheels. The animals were given access to food once a day for varying amounts of time ranging from one to twenty-four hours (no food restriction).

The rats received food on restricted schedules began to spend more time running. Clearly, the increased running was counterproductive, because these animals lost much more weight than the animals housed in cages without running wheels.

One explanation for the increased activity of rats on a semistarvation diet is that it reflects an innate tendency to seek food when it becomes scarce.

Normally, rats would expend their activity by exploring the environment and searching for food, but because of their confinement, the tendency to explore results only in futile wheel running.

The fact that starving rats increase their activity suggests that the excessive activity of anorexic patients and the people subjected to the extreme conditions during the Hunger Winter may be a symptom of starvation, not a weight-loss strategy.

Blood levels of NPY are elevated in patients with anorexia. NPY normally stimulates eating. Nergårdh et al. (2007) found that intracerebroventricular infusions of NPY further increased the time spent running in rats on a restricted feeding schedule. Normally, NPY stimulates eating (as it did in rats with unlimited access to food), but under conditions of starvation, it stimulates wheel-running activity instead.

Why anorexia gets started in the first place? Even if the symptoms of anorexia are largely those of starvation, what begins the behavior that leads to starvation?

- The simple answer is that we still do not know

One possibility is a genetic predisposition for this behavior. There is good evidence, primarily from twin studies, that hereditary factors play an important role in the development of anorexia nervosa.

In addition, the incidence of anorexia nervosa is higher in girls who were born prematurely or who had sustained birth trauma during complicated deliveries, which suggests that biological factors independent of heredity may play a role.

The fact that anorexia nervosa is seen primarily in young women has prompted both biological and social explanations.

Most psychologists favor the latter, concluding that the emphasis placed on slimness by most modern societies—especially in women—is responsible for this disorder.

Another possible cause could be the changes in hormones that accompany puberty.

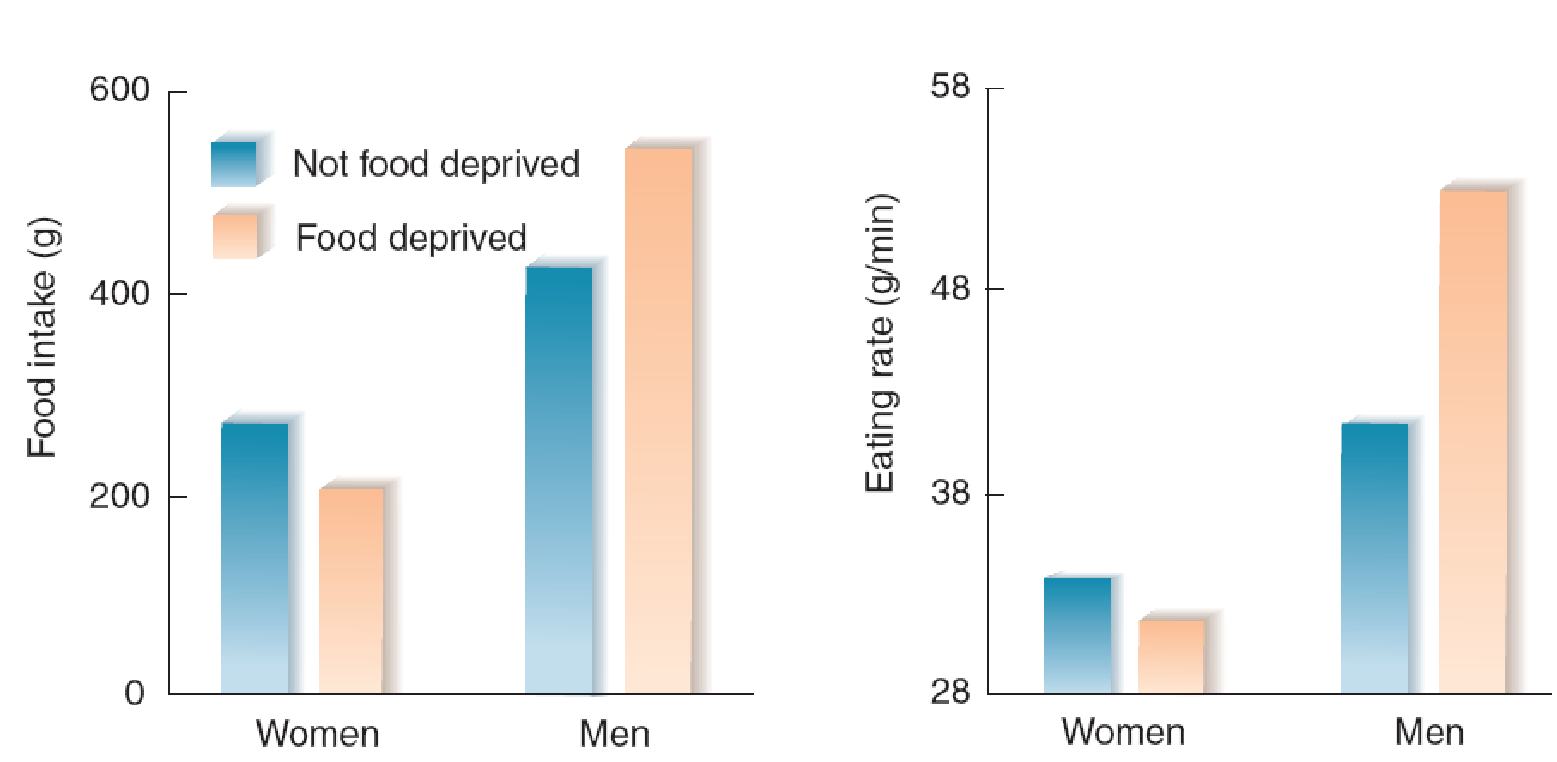

Young men and women differ in their response to even a short period of fasting. Södersten, Bergh, and Zandian (2006) had high school students visit their laboratory at noon. They had been fasting since lunch on the previous day. The men ate more food than they had the first time. However, the women actually ate less than they had before.

Reactions of Young Men and Women to Fasting:

- The graph shows the food intake and eating rate of young men and women during a buffet lunch after a twenty-four-hour period of fasting or after a period during which they ate meals at their normal times.

Apparently, women have difficulty compensating for a period of food deprivation by eating more food. As the authors note, “dieting may be dangerous in women and in particular in those who are physically active and therefore need to eat more food, such as athletes”.

Perhaps some young women (and a small number of young men) go on a diet to bring their body weight closer to what they perceive as ideal. Once they get set on this course and begin losing weight, physiological and endocrinological changes bring about the symptoms of starvation outlined previously, and the vicious circle begins.

In fact, at the end of the Minnesota semistarvation study when the volunteers were permitted to eat normally again, A few of them displayed symptoms of anorexia, engaging in dieting behavior and complaining about the fat in their abdomens and thighs (Keys et al., 1950). This phenomenon suggests that strongly restricted access to food can apparently produce anorexia in people (men, in this case) with a predisposition to this disorder.

Treatment

Anorexia is very difficult to treat successfully.

Cognitive behavior therapy, considered by many clinicians to be the most effective approach, has a success rate of less than 50% and a relapse rate of 22% during a one-year treatment period (Pike et al., 2003).

The success rate in treating anorexia has not improved in the last fifty years.

Researchers have tried to treat anorexia nervosa with many drugs that increase appetite in laboratory animals or in people without eating disorders.

For example, antipsychotic medications, drugs that stimulate adrenergic α2 receptors, l-DOPA, and THC (the active ingredient in marijuana).

Unfortunately, none of these drugs has been shown to be helpful (Mitchell, 1989).