L6 Sleep, Awake and Consciousness

Learning Objectives

Part I

Describe the course of a night’s sleep: its stages and their characteristics.

Discuss insomnia, sleeping medications, and sleep apnea.

Discuss narcolepsy and sleep disorders associated with REM sleep and slow-wave sleep.

Review the hypothesis that sleep serves as a period of restoration by discussing the effects of sleep deprivation, exercise, and mental activity.

Discuss research on the effects of REM sleep and slow-wave sleep on learning.

Part II

Evaluate evidence that the onset and amount of sleep is chemically controlled, and describe the neural control of arousal.

Discuss the neural control of slow-wave sleep, including the sleep/waking flip-flop and the role of orexinergic neurons.

Discuss the neural control of REM sleep, including the REM sleep flip-flop.

Describe circadian rhythms and discuss research on the neural and physiological bases of these rhythms.

一、A Physiological and Behavioral Description of Sleep

Methods to Study Sleep

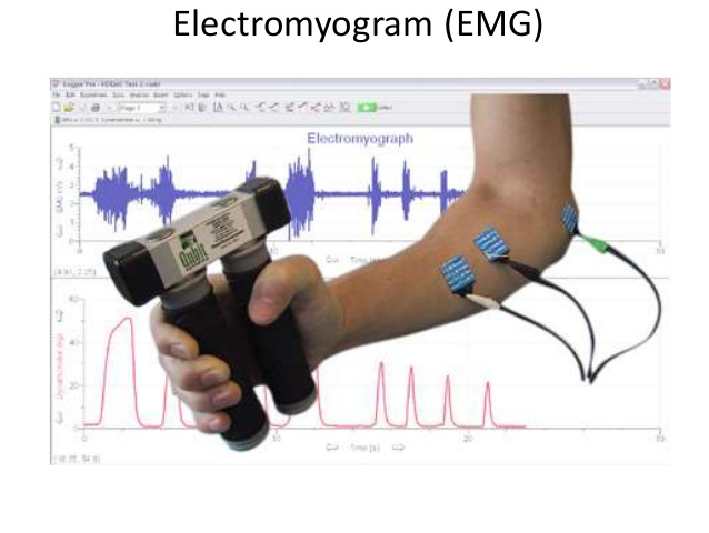

Electromyogram (EMG)

- An electrical potential recorded from an electrode placed on or in a muscle.

Electro-oculogram (EOG)

- An electrical potential from eyes, recorded by means of electrodes placed on skin around them; detects eye movements.

- A Subject Prepared for a Night’s Sleep in a Sleep Laboratory

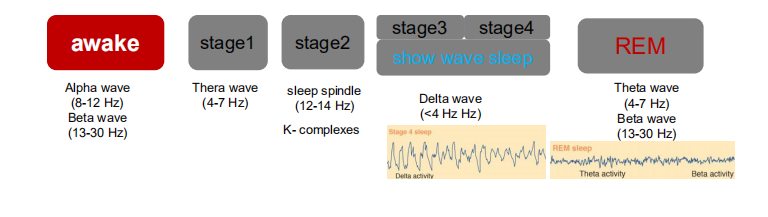

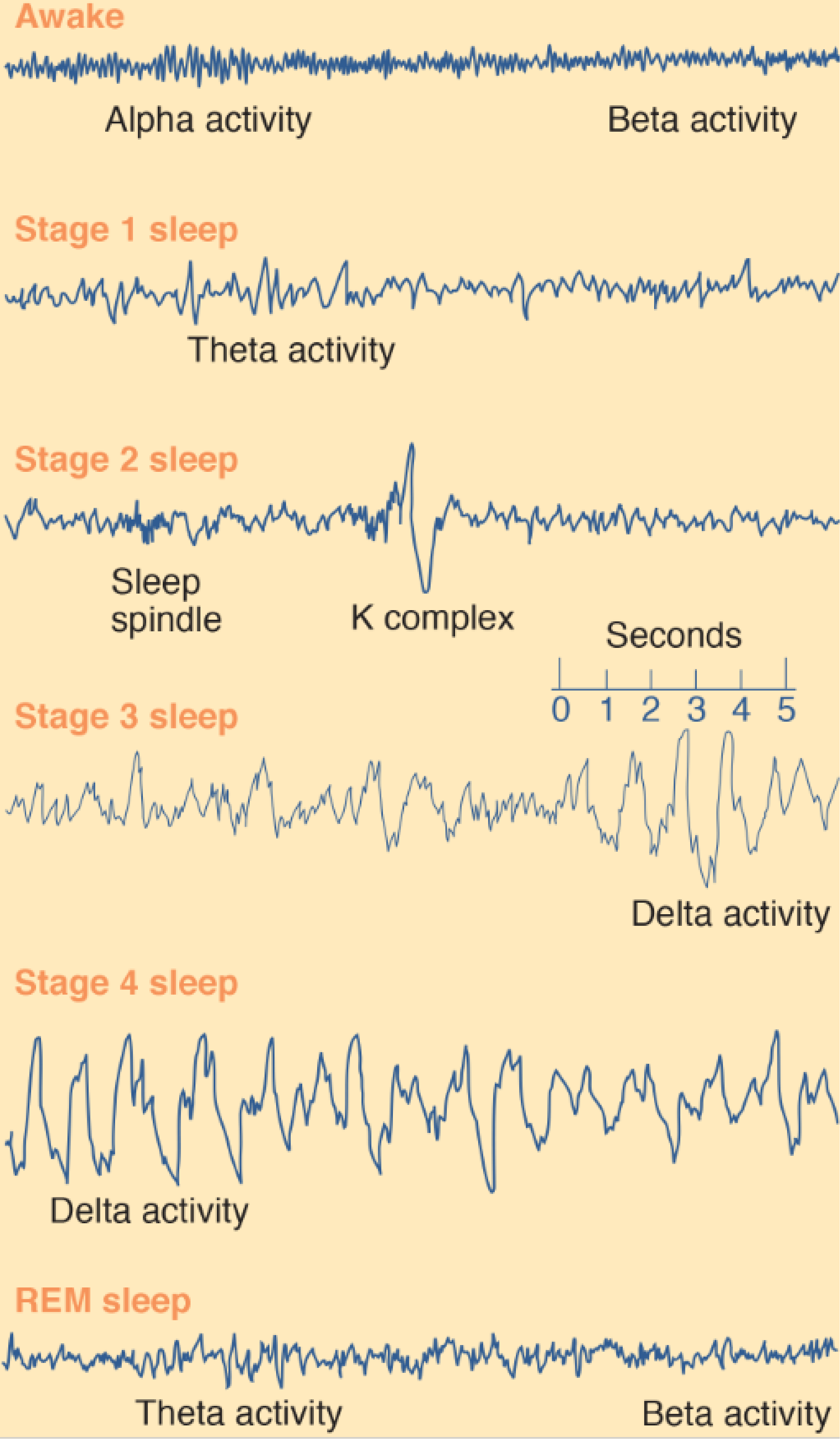

Electroencephalography(EEG) Recording of the Stages of Sleep

- Alpha activity: Smooth electrical activity of 8–12 Hz recorded from the brain; generally associated with a state of relaxation.

- Theta activity: Electroencephalography (脑电图学) activity of 3.5–7.5 Hz that occurs intermittently(间歇地) during early stages of slow-wave sleep and REM sleep.

- K complexes: Sharp, large waves that occur about once a minute.

- Sleep spindles: Brief bursts of 12 -14 Hz waves that appear to serve a gating function, preventing disruptive stimuli from reaching the cortex and waking the sleeper.

- Delta activity: Regular, synchronous electrical activity of less than 4 Hz recorded from the brain; occurs during deepest stages of slow-wave sleep.

Electroencephalography Recording of the Stages of Sleep

Stages of Sleep

Principal Characteristics of REM and Slow-Wave Sleep

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep

- Period of desynchronized electroencephalography activity during sleep, at which time dreaming, rapid eye movements, and muscular paralysis occur; also called paradoxical sleep.

Slow-wave sleep

- Non-REM sleep, characterized by synchronized electroencephalography activity during its deeper stages.

- If we arouse our volunteer during REM sleep and ask her what was going on, she will almost certainly report that she had been dreaming. The dreams of REM sleep tend to be narrative in form, with a storylike progression of events. On the other hand, if we wake her during slow-wave sleep and ask, “Were you dreaming?” she will most likely say, “No.” However, if we question her more carefully, she might report the presence of a thought, an image, or some emotion.

| REM Sleep | Slow-Wave Sleep |

|---|---|

| Electroencephalography desynchrony (rapid, irregular waves) | Electroencephalography synchrony (slow waves) |

| Lack of muscle tonus | Moderate muscle tonus |

| Rapid eye movements | Slow or absent eye movements |

| Genital activity | Lack of genital activity |

| Dreams | No data |

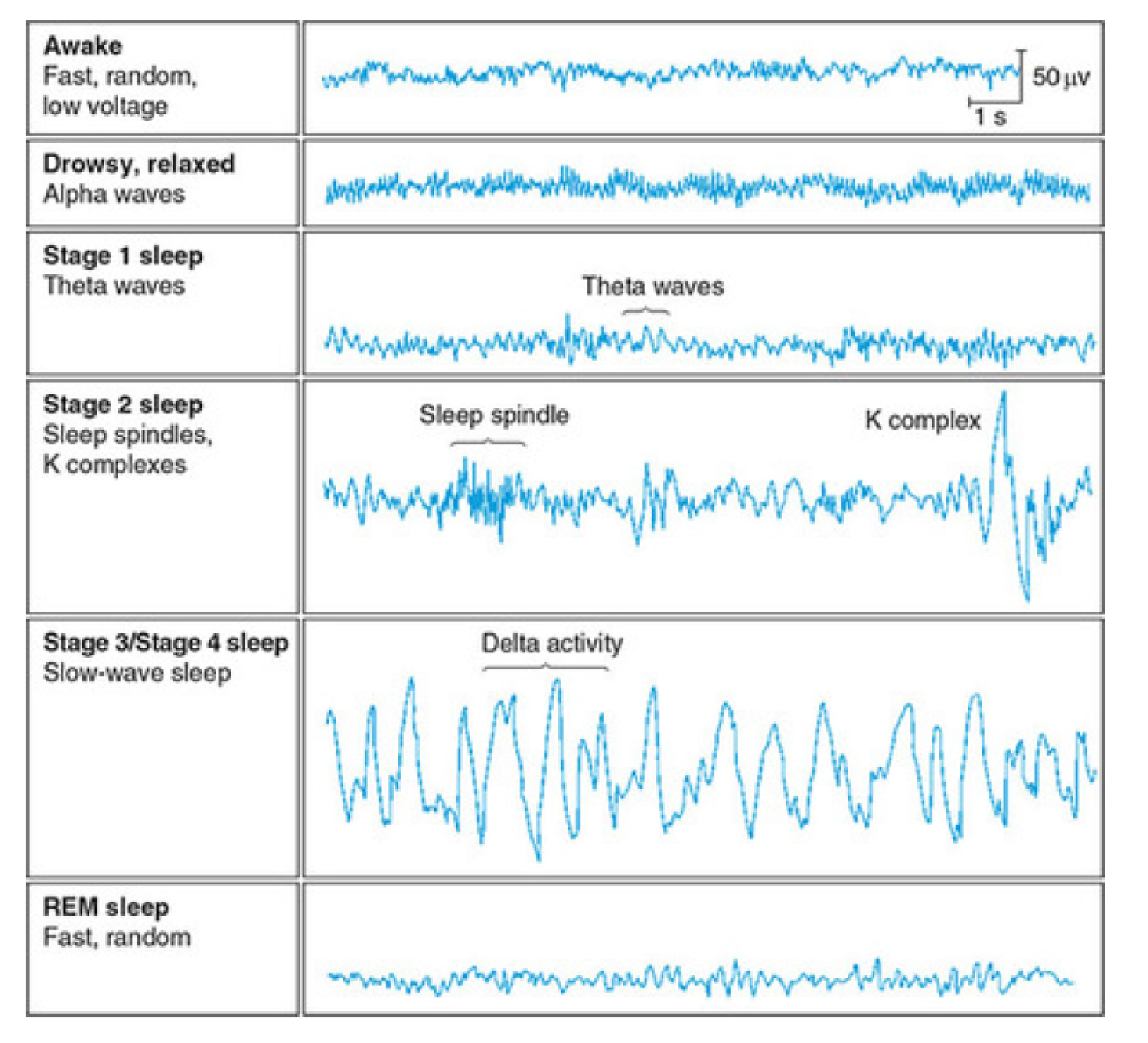

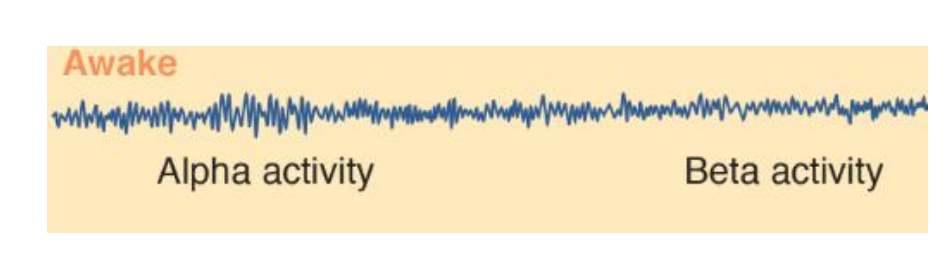

1. Awake

During wakefulness the EEG of a normal person shows two basic patterns of activity: alpha activity and beta activity.

- Alpha activity consists of regular, medium-frequency waves of 8–12 Hz. The brain produces this activity when a person is resting quietly, not particularly aroused or excited and not engaged in strenuous mental activity (such as problem solving). Although alpha waves sometimes occur when a person’s eyes are open, they are much more prevalent when they are closed.

- Beta activity , consists of irregular, mostly low-amplitude waves of 13–30 Hz. Beta activity shows desynchrony; it reflects the fact that many different neural circuits in the brain are actively processing information. Desynchronized activity occurs when a person is alert and attentive to events in the environment or is thinking actively.

2. Stage 1 Sleep

The subject becomes drowsy and soon enters stage 1 sleep, marked by the presence of some theta activity (3.5–7.5 Hz), which indicates that the firing of neurons in the neocortex is becoming more synchronized.

This stage is actually a transition between sleep and wakefulness; if we watch our volunteer’s eyelids, we will see that from time to time they slowly open and close and that her eyes roll upward and downward.

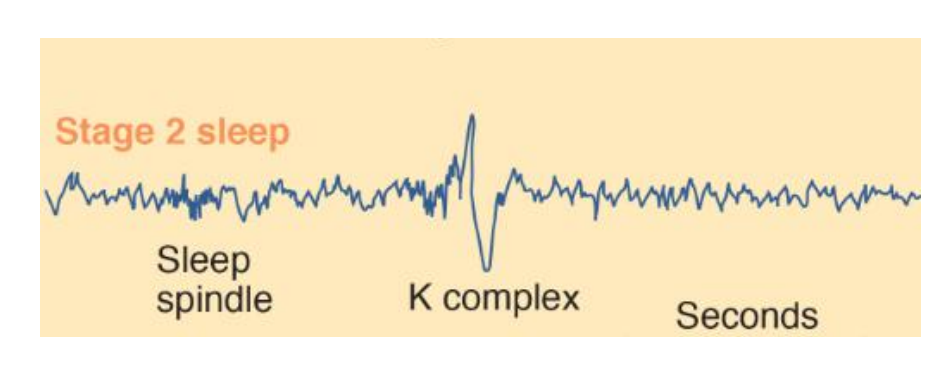

3. Stage 2 Sleep

About ten minutes later she enters stage 2 sleep. The EEG during this stage is generally irregular but contains periods of theta activity, sleep spindles, and K complexes.

Sleep spindles are short bursts of waves of 12–14 Hz that occur between two and five times a minute during stages 1–4 of sleep.

- K complexes appear to play a role in the consolidation of memories, and increased numbers of sleep spindles are correlated with increased scores on tests of intelligence (Fogel and Smith, 2011).

- They are sudden, sharp waveforms that, unlike sleep spindles, are usually found only during stage 2 sleep. They spontaneously occur at the rate of approximately one per minute but often can be triggered by noises—especially unexpected noises.

- Cash et al. (2009) recorded the activity of single neurons in the human cerebral cortex during sleep and found that K complexes consisted of isolated periods of neural inhibition. (The recordings were made from the brains of patients who were being evaluated for neurosurgery.) K complexes appear to be the forerunner of delta waves, which appear in the deepest levels of sleep.

The subject is sleeping soundly now; if awakened, however, she might report that she has not been asleep. This phenomenon often is reported by nurses who awaken loudly snoring hospital patients early in the night (probably to give them a sleeping pill) and find that the patients insist that they were lying there awake all the time.

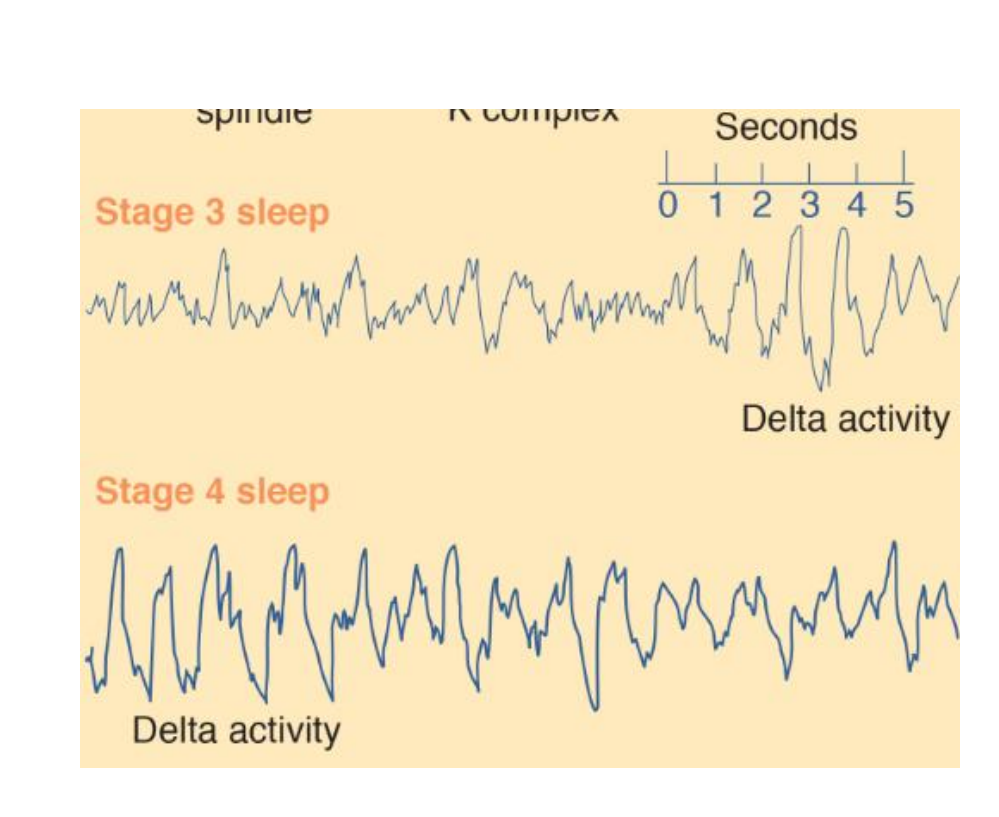

4. Stage 3 and Stage 4 Sleep

About fifteen minutes later the subject enters stage 3 sleep, signaled by the occurrence of high-amplitude delta activity (slower than 3.5 Hz). The distinction between stage 3 and stage 4 is not clear-cut; stage 3 contains 20–50 percent delta activity, and stage 4 contains more than 50 percent. Because slow-wave EEG activity predominates during sleep stages 3 and 4, they are collectively referred to as slow-wave sleep .

In recent years, researchers have begun studying the details of the EEG activity that occurs during slow-wave sleep and the brain mechanisms responsible for this activity (Steriade, 2003, 2006). It turns out that the most important feature of slow-wave activity during sleep is the presence of slow oscillations of less than 1 Hz. Each oscillation consists of a single high-amplitude biphasic (down and up) wave of slightly less than 1 Hz. The first part of the wave indicates a down state—a period of inhibition during which neurons in the neocortex are absolutely silent. Presumably, it is during this down state that neocortical neurons are able to rest. The second part indicates an up state—a period of excitation during which these neurons briefly fire at a high rate.

By most criteria, stage 4 is the deepest stage of sleep.

5. REM Sleep

About ninety minutes after the beginning of sleep (and about forty-five minutes after the onset of stage 4 sleep), we notice an abrupt change in a number of physiological measures recorded from our subject.

The EEG suddenly becomes mostly desynchronized, with a sprinkling of theta waves, very similar to the record obtained during stage 1 sleep. We also note that her eyes are rapidly darting back and forth beneath her closed eyelids. We can see this activity in the EOG (Electro-oculogram), recorded from electrodes attached to the skin around her eyes, or we can observe the eye movements directly—the cornea produces a bulge in the closed eyelids that can be seen to move about. We also see that the EMG becomes silent; there is a profound loss of muscle tone. In fact, physiological studies have shown that, aside from occasional twitching, a person actually becomes paralyzed during REM sleep. This peculiar stage of sleep is quite distinct from the quiet sleep we saw earlier. It is usually referred to as REM sleep (for the rapid eye movements that characterize it).

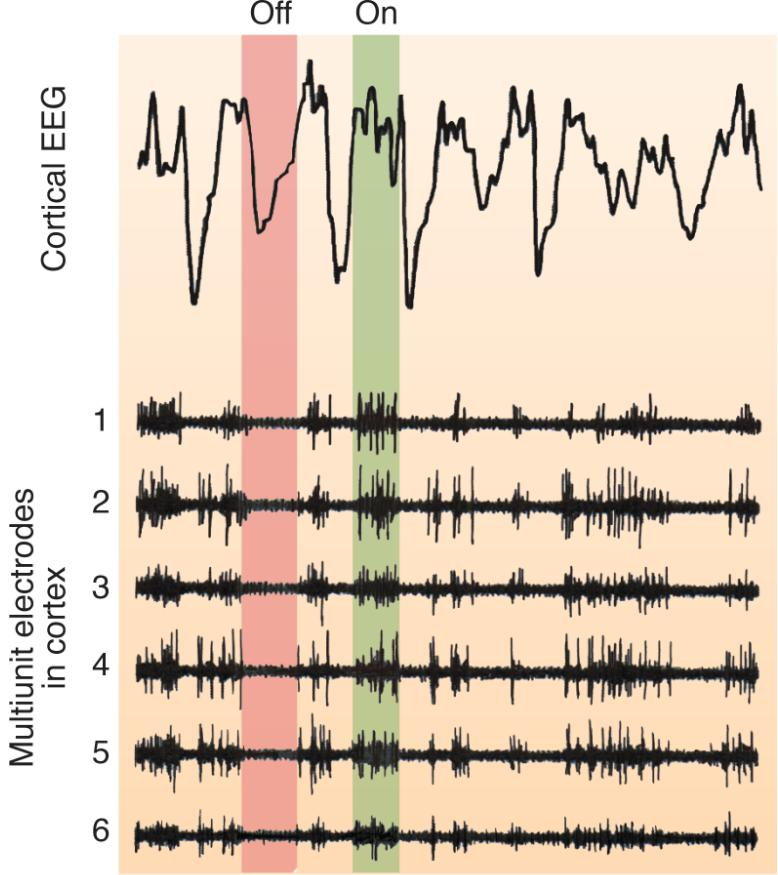

Electroencephalography and Single-Cell Activity during slow-wave sleep

Upstate

- A period of excitation during a slow oscillation during slow-wave sleep; neurons in the neocortex briefly fire at a high rate.

Down state

- A period of inhibition during a slow oscillation during slow-wave sleep; neurons in the neocortex are silent and resting.

Recordings of cortical electroencephalography and multiunit cell activity during slow-wave sleep of a rat. The top of the figure shows several slow oscillations. During the descending phase of the slow oscillation (down state, indicated in red), the neurons are hyperpolarized and do not fire. During the ascending phase (up state, indicated in green), the neurons fire.

Each sleep cycle is approximately 90 minutes long, containing a 20 – 30 minute bout of REM sleep.

- Thus, an 8 - hour sleep will contain four or 5 periods of REM sleep.

- In this typical pattern of sleep stages, the dark blue shading indicates REM sleep.

During the rest of the night our subject’s sleep alternates between periods of REM and non-REM sleep. Each cycle is approximately ninety minutes long, containing a twenty- to thirty-minute bout of REM sleep. Thus, an eight-hour sleep will contain four or five periods of REM sleep. This figure shows a graph of a typical night’s sleep. The vertical axis indicates the EEG activity that is being recorded; thus, REM sleep and stage 1 sleep are placed on the same line because similar patterns of EEG activity occur at these times.

- Note that most slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4) occurs during the first half of night.

- Subsequent bouts of non-REM sleep contain more and more stage 2 sleep, and bouts of REM sleep (indicated by the horizontal bars) become more prolonged.

Disorders of Sleep

1. Insomnia 失眠症

Because we spend about one-third of our lives sleeping, sleep disorders can have a significant impact on our quality of life. They can also affect the way we feel while we are awake.

Insomnia is a problem that is said to affect approximately 25 percent of the population occasionally and 9 percent regularly.

Insomnia is characterized as difficulty falling asleep after going to bed or after awakening during the night. But a significant problem in identifying insomnia is the unreliability of self-reports.

A significant problem in identifying insomnia is the unreliability of self-reports. Most patients who receive a prescription for a sleeping medication are given one on the basis of their own description of their symptoms. That is, they tell their physician that they sleep very little at night, and the drug is prescribed on the basis of this testimony. Very few patients are observed during a night’s sleep in a sleep laboratory; thus, insomnia is one of the few medical problems that physicians treat without having direct clinical evidence for its existence. But studies on the sleep of people who complain of insomnia show that most of them underestimate the amount of time they actually spend sleeping.

For many years the goal of sleeping medication was to help people fall asleep, and when drug companies evaluated potential medications, they concentrated on that property. However, if we think about the ultimate goal of sleeping medication, it is to make the person feel more refreshed the next day. If a medication puts people to sleep right away but produces a hangover of grogginess and difficulty concentrating the next day, it is worse than useless. In fact, many drugs that are traditionally used to treat insomnia had just this effect. Researchers have now recognized that the true evaluation of a sleeping medication must be made during wakefulness the following day, and “hangover-free” drugs are finally being developed (Hajak et al., 1995; Ramakrishnan and Scheid, 2007).

Many people spend much of their time in a sleep-deprived state not because they suffer from insomnia, but because the demands of their daily schedules lead them to stay up late or get up early (or both), thus receiving less than the optimal amount of sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation can lead to serious health problems, including increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Orzel-Gryglewska, 2010).

2. Sleep Apnea 睡眠呼吸中止症

Cessation of breathing while sleeping.

Patients with this disorder, called sleep apnea, fall asleep and then cease to breathe.

- (Apnos is Greek for “without breathing.”)

Nearly all people, especially people who snore(打鼾), have occasional episodes of sleep apnea, but not to the extent that it interferes with sleep.

During a period of sleep apnea the level of carbon dioxide in the blood stimulates chemoreceptors (neurons that detect the presence of certain chemicals), and the person wakes up, gasping for air. The oxygen level of the blood returns to normal, the person falls asleep, and the whole cycle begins again. Because sleep is disrupted, people with this disorder typically feel sleepy and groggy during the day. Fortunately, many cases of sleep apnea are caused by an obstruction of the airway that can be corrected surgically or relieved by a device that attaches to the sleeper’s face and provides pressurized air that keeps the airway open.

3. Narcolepsy 猝睡症;嗜睡症

Introduction

(narke means “numbness,” and lepsis means “seizure”)

It is a neurological disorder characterized by sleep (or some of its components) at inappropriate times. The symptoms can be described in terms of what we know about the phenomena of sleep. The primary symptom of narcolepsy is the sleep attack. The narcoleptic sleep attack is an overwhelming urge to sleep that can happen at any time but occurs most often under monotonous, boring conditions. Sleep (which appears to be entirely normal) generally lasts for 2–5 minutes. The person usually wakes up feeling refreshed.

Another symptom of narcolepsy—in fact, the most striking one—is cataplexy (from kata, “down,” and plexis, “stroke”). During a cataplectic attack a person will sustain varying amounts of muscle weakness. In some cases, the person will become completely paralyzed and slump down to the floor. The person will lie there, fully conscious, for a few seconds to several minutes. What apparently happens is that one of the phenomena of REM sleep—muscular paralysis—occurs at an inappropriate time. This loss of tonus is caused by massive inhibition of motor neurons in the spinal cord. When this happens during waking, the victim of a cataplectic attack loses control of his or her muscles. As in REM sleep, the person continues to breathe and is able to control eye movements. (The brain abnormality responsible for narcolepsy is described later.)

Cataplexy is quite different from a narcoleptic sleep attack; cataplexy is usually precipitated by strong emotional reactions or by sudden physical effort, especially if the patient is caught unawares. Laughter, anger, or an effort to catch a suddenly thrown object can trigger a cataplectic attack. In fact, as Guilleminault, Wilson, and Dement (1974) noted, even people who do not have cataplexy sometimes lose muscle strength after a bout of intense laughter. (Perhaps that is why we say a person can become “weak from laughter.”)

There is case reported that a patient had his first cataplectic attack when he was addressing the board of directors of the company he worked for.

Wise (2004) notes that patients with narcolepsy often try to avoid thoughts and situations that are likely to evoke strong emotions because they know that these emotions are likely to trigger cataplectic attacks.

Example:

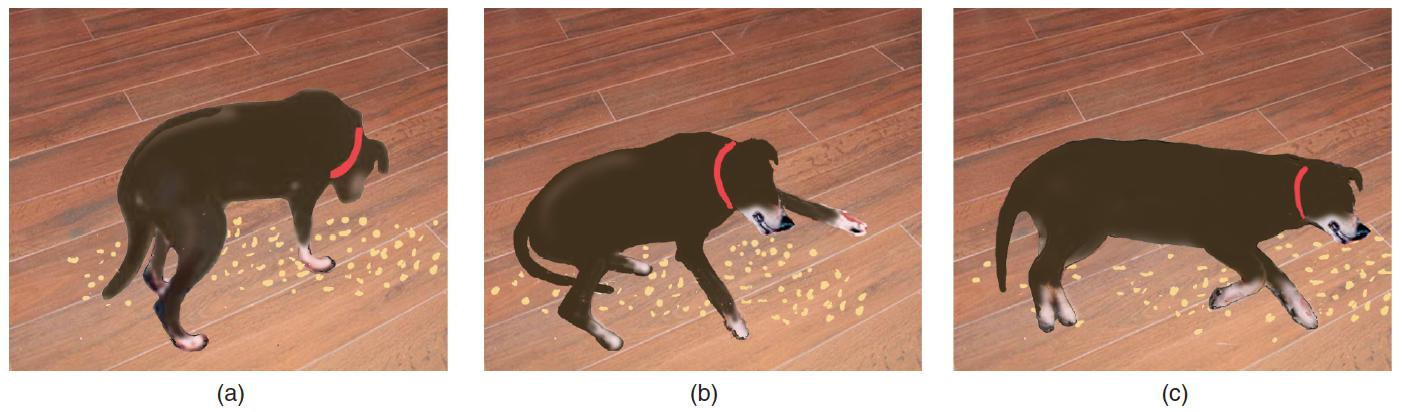

A Dog Undergoing a Cataplectic Attack

- The attack was triggered by the dog’s excitement at finding some food on the floor. (a) The dog sniffs the food. (b) Muscles begin to relax. (c) The dog is temporarily paralyzed, as it would be during REM sleep.

REM sleep paralysis sometimes intrudes into waking at a time that does not present any physical danger—just before or just after normal sleep, when a person is already lying down. This symptom of narcolepsy is referred to as sleep paralysis , an inability to move just before the onset of sleep or upon waking in the morning.

A person can be snapped out of sleep paralysis by being touched or by hearing someone call his or her name. Sometimes, the mental components of REM sleep intrude into sleep paralysis; that is, the person dreams while lying awake, paralyzed. These episodes, called hypnagogic hallucinations , are often alarming or even terrifying. (The term hypnagogic comes from the Greek words hupnos, “sleep,” and agogos, “leading.”) For example, during a hypnagogic hallucination a patient thought that his former roommate was trying to attack him with a hammer.

Symptoms of Narcolepsy

Sleep attack

- An irresistible urge to sleep during the day, after which the person awakens feeling refreshed.

Cataplexy

- Complete paralysis that occurs during waking.

Sleep paralysis

- Paralysis occurring just before a person falls asleep.

Hypnagogic hallucination

- Vivid dreams that occur just before a person falls asleep; accompanied by sleep paralysis.

Fortunately, human narcolepsy is relatively rare, with an incidence of approximately 1/2000. This hereditary disorder appears to involve a gene found on chromosome 6, but it is strongly influenced by unknown environmental factors (Mignot, 1998; Mahowald and Schenck, 2005; Nishino, 2007).

Years ago, researchers began a program to maintain breeds of dogs that are afflicted with narcolepsy, with the hopes that discovery of the causes of canine narcolepsy would further our understanding of the causes of human narcolepsy. Lin et al. (1999) discovered that a mutation of a specific gene is responsible for canine narcolepsy. The product of this gene is a receptor for a peptide neurotransmitter called hypocretin by some researchers, and called orexin by others.

- The name hypocretin comes from the fact that the lateral hypothalamus contains the cell bodies of all of the neurons that secrete this peptide.

- The name orexin comes from the role this peptide plays in the control of eating and metabolism (Orexis means “appetite” in Greek.) Two laboratories independently discovered the peptide; hence, it has two names.

Chemelli et al. (1999) prepared a targeted mutation in mice against the orexin gene and found that the animals showed symptoms of narcolepsy. Like human patients with narcolepsy, they went directly into REM sleep from waking and showed periods of cataplexy while they were awake.

Gerashchenko et al. (2001, 2003) prepared a toxin that attacked only orexinergic neurons, which they then administered to rats. The destruction of the orexin system produced the symptoms of narcolepsy.

In humans, narcolepsy appears to be caused by a hereditary autoimmune disorder.

Most patients with narcolepsy are born with orexinergic neurons, but during adolescence the immune system attacks these neurons, and the symptoms of narcolepsy begin.

The symptoms of narcolepsy can be treated with drugs. Sleep attacks can be diminished by stimulants such a methylphenidate (Ritalin), a catecholamine agonist (Vgontzas and Kales, 1999).

The REM sleep phenomena (cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations) have traditionally been treated with antidepressant drugs, which facilitate both serotonergic and noradrenergic activity.

4. REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

As you now know, REM sleep is accompanied by paralysis. Although neurons in the motor cortex and subcortical motor systems are extremely active during REM sleep (McCarley and Hobson, 1979), people are unable to move at this time. (The occasional twitches that are seen during REM sleep are apparently signs of intense activity of motor neurons that are not completely suppressed.)

- The fact that people are paralyzed while they dream suggests the possibility that, if not for the paralysis, they would act out their dreams. Indeed, they would.

Schenck et al. (1986) reported the existence of an interesting disorder: REM sleep behavior disorder . The behavior of people with this disorder corresponds with the contents of their dreams.

Introduction

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

- A neurological disorder in which the person does not become paralyzed during REM sleep and thus acts out dreams.

A case of REM sleep behavior disorder

I was a halfback playing football, and after the quarterback received the ball from the center he lateraled it sideways to me and I’m supposed to go around end and cut back over tackle and—this is very vivid—as I cut back over tackle there is this big 280-pound tackle waiting, so I, according to football rules, was to give him my shoulder and bounce him out of the way . . . when I came to I was standing in front of our dresser and I had [gotten up out of bed and run and] knocked lamps, mirrors and everything off the dresser, hit my head against the wall and my knee against the dresser. (Schenck et al., 1986, p. 294)

Like narcolepsy, REM sleep behavior disorder appears to be a neurodegenerative disorder with at least some genetic component (Schenck et al. 1993).

It is often associated with better-known neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease (Boeve et al. 2007).

- The symptoms of REM sleep behavior disorder are the opposite of those of cataplexy; that is, rather than exhibiting paralysis outside REM sleep, patients with REM sleep behavior disorder fail to exhibit paralysis during REM sleep.

As you might expect, the drugs that are used to treat the symptoms of cataplexy will aggravate the symptoms of REM sleep behavior disorder (Schenck and Mahowald, 1992). REM sleep behavior disorder is usually treated by clonazepam, a benzodiazepine tranquilizer(Aurora et al., 2010; Frenette, 2010).

5. Problems Associated with Slow-Wave Sleep

Some maladaptive behaviors occur during slow-wave sleep, especially during its deepest phase, stage 4. These behaviors include bedwetting (nocturnal enuresis), sleepwalking (somnambulism), and night terrors (pavor nocturnus). All three events occur most frequently in children. Often bedwetting can be cured by training methods, such as having a special electronic circuit ring a bell when the first few drops of urine are detected in the bed sheet (a few drops usually precede the ensuing flood). Night terrors consist of anguished screams, trembling, a rapid pulse, and usually no memory of what caused the terror. Night terrors and somnambulism usually cure themselves as the child gets older. Neither of these phenomena is related to REM sleep; a sleepwalking person is not acting out a dream. Especially when it occurs in adulthood, sleepwalking appears to have a genetic component(Hublin et al., 1997).

Two cases of Sleepwalking

One evening Ed Weber got up from a nap on the sofa, polished off a half-gallon of chocolate chip ice cream, then dozed off again. He woke up an hour later and went looking for the ice cream, summoning his wife to the kitchen and insisting, to her astonishment, that someone else must have eaten it.

Television talk show host Montel Williams . . . told viewers he had removed raw foods from his refrigerator because “I wake up in the morning and there’s a pack of chicken and there’s a bite missing out of it. . . . I can take a whole pound of ham or bologna . . . and then wake up in the morning and not realize that I had [eaten] it and ask, ‘Who ate my lunch meat?’” (Boodman, 2004, p. HE01)

Sleep-related eating disorder

A disorder in which the person leaves his or her bed and seeks out and eats food while sleepwalking, usually without a memory for the episode the next day.

Sleep-related eating disorder usually responds well to dopaminergic agonists or topiramate, an antiseizure medication, and may be provoked by zolpidem, a benzodiazepine agonist that has been used to treat insomnia (Howell and Schenck, 2009). An increased incidence of nocturnal eating in family members of people with this disorder suggests that heredity may play a role (De Ocampo et al., 2002).

Why Do We Sleep? - The functions of Sleep

Each night, we slip into a mysterious state that is neither entirely conscious nor unconscious. Sleep has intrigued humans throughout history:

- Metaphysically, dreaming suggested to our forebears that the soul took leave of the body at night to wander the world; practically, sleep is a period of enforced nonproductivity and vulnerability to predators and enemies.

In spite of thousands of research studies, we are still unclear on the most basic question — What is the function of sleep?

The most obvious explanation is that sleep is restorative. Support for this idea comes from the observation that species with higher metabolic rates typically spend more time in sleep (Zepelin & Rechtschaffen, 1974).

A less obvious explanation is the adaptive hypothesis; according to this view, the amount of sleep an animal engages in depends on the availability of food and on safety considerations (Webb, 1974).

Sleep Time

Observations support the hypothesis that sleep is an adaptive response to feeding and safety needs

- Source: Based on data from “Animal Sleep: A Review of Sleep Duration Across Phylogeny,” by S. S. Campbell and I. Tobler, 1984, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 8, pp. 269–300.

- Elephants, for instance, which must graze for many hours to meet their food needs, sleep briefly. Animals withlow vulnerability to predators, such as the lion, sleep much of the time, as do animals that find safety by hiding, like bats and burrowing animals. Vulnerable animals that are too large to burrow or hide—for example,horses and cattle—sleep very little. In a study of 39 species, the combined factors of body size and danger accounted for 80% of the variability in sleep time (Allison & Cicchetti, 1976).

The Function of Clean

An interesting new idea is that the brain cleanses itself of toxins during sleep.

Researchers at the University of Rochester in New York recently discovered a network of channels formed by glia, which transport cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the brain. By injecting a colored dye in the brains of mice as they slept and a dye of another color when they woke up, the researchers determined that large amounts of CSF flowed through the brain during sleep but not during the awake state.

- The researchers then injected β-amyloid proteins into the brains of the mice and found that the CSF cleared the proteins out of cells twice as fast during sleep (Xie et al., 2013).

Sleep deprivation study

Shift workers sleep less than day workers, and their work performance suffers as a result (Tepas & Carvalhais, 1990). With their work and sleep schedules at odds with their biological rhythms, shift workers find that sleep intrudes into their work and daytime arousal interferes with their sleep.

Another study with mice may give us a clue why this happens. After just a few days of sleeping three to five hours a day, the mice had lost 25% of the neurons in the locus coeruleus, a part of the brain that is important for alertness (J. Zhang et al., 2014).

In long-term sleep deprivation studies, impairment follows a rhythmic cycle—performance declines during the night and then shows some recovery during the daytime (Horne, 1988). The persistence of this rhythm represents a safety hazard of gigantic proportions when people try to function at night. The largest number of single-vehicle traffic accidents attributed to “falling asleep at the wheel” occur around 2 a.m. (Mitler et al., 1988), and the number of work errors peaks at the same time (Broughton, 1975). In addition, the Three Mile Island nuclear plant accident took place at 4 a.m.; the Chernobyl nuclear plant meltdown began at 1:23 a.m.

Travel across time zones also disrupts sleep and impairs performance, particularly when you travel eastward. It is difficult to quantify the effects of jet lag, but three researchers have attempted to do so in a novel way by comparing the performance of baseball teams. When East Coast and West Coast teams played at home, their percentage of wins was nearly identical —50% and 49%, respectively. When they traveled across the continent but had time to adjust to the new time zone, they showed a typical visitor’s disadvantage, winning 45.9% of their games. Teams traveling west without time to adjust won about the same, 43.8% of their games, whereas teams traveling east won only 37.1% (Recht, Lew, & Schwartz, 1995). Sleep quality is better when you extend the day’s length by traveling west, rather than shorten it as you do when you travel east. One way of looking at this effect is that it is easier to stay awake past your bedtime than it is to go to sleep when you are not sleepy.

We all know how insistent the urge to sleep can be and how uncomfortable we feel when we have to resist it and stay awake. With the exception of the effects of severe pain and the need to breathe, sleepiness is probably the most insistent drive that we can experience. People can commit suicide by refusing to eat or drink, but even the most stoical person cannot indefinitely defy the urge to sleep. Sleep will come, sooner or later, no matter how hard a person tries to stay awake.

Although the issue is not yet settled, most researchers believe that the primary function of slow-wave sleep is to permit the brain to rest.

In addition, slow-wave sleep and REM sleep promote different types of learning, and REM sleep also appears to promote brain development.

1. Functions of Slow-Wave Sleep

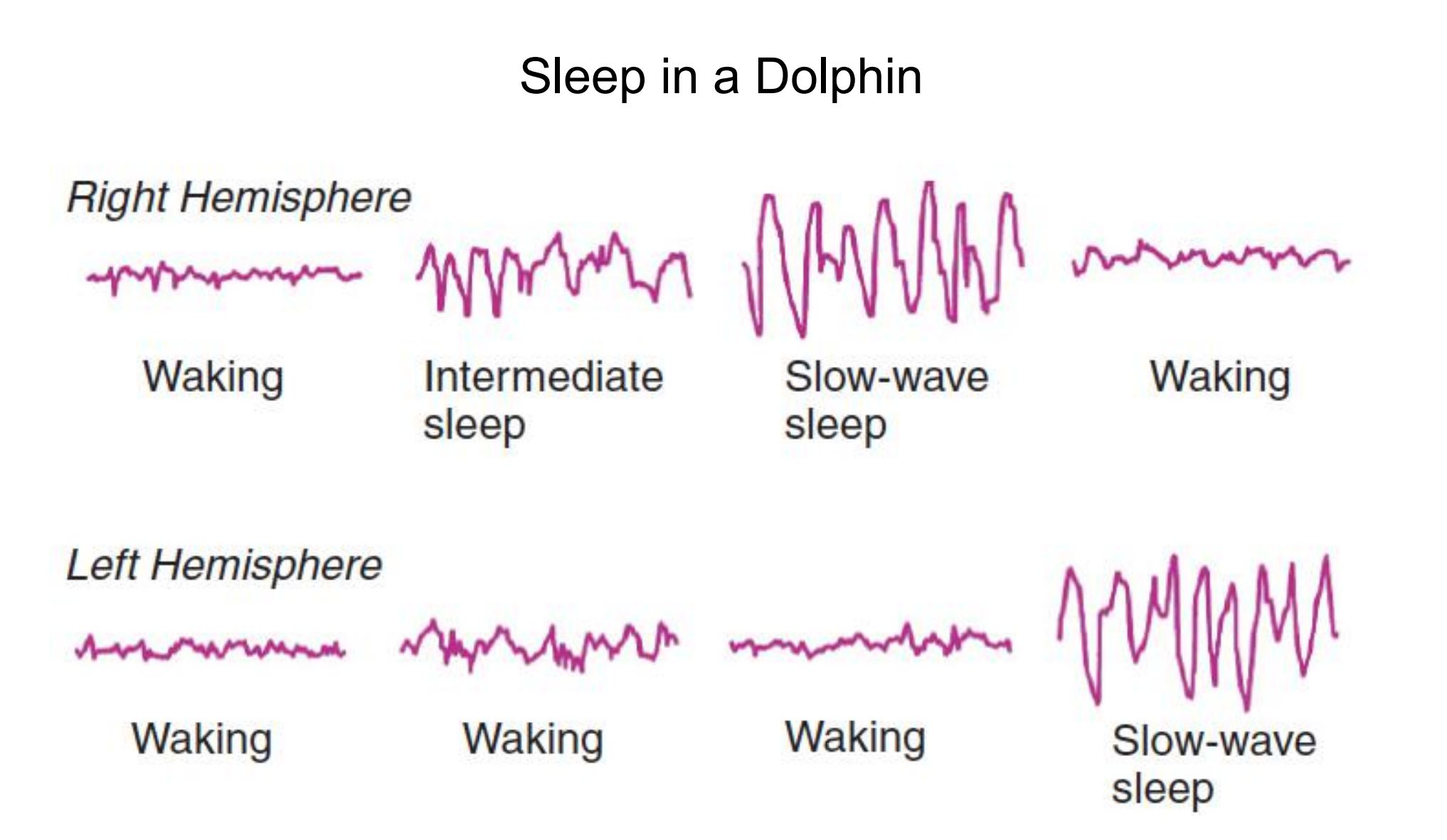

Sleep is a universal phenomenon among vertebrates. As far as we know, all mammals and birds sleep (Durie, 1981). Reptiles also sleep, and fish and amphibians enter periods of quiescence that probably can be called sleep.

- However, only warm-blooded vertebrates (mammals and birds) exhibit unequivocal REM sleep, with muscular paralysis, EEG signs of desynchrony, and rapid eye movements.

Sleep appears to be essential to survival. Evidence for this assertion comes from the fact that sleep is found in some species of mammals that would seem to be better off without it.

For example, some species of marine mammals have developed an extraordinary pattern of sleep: The cerebral hemispheres take turns sleeping, presumably because that strategy always permits at least one hemisphere to be alert and keep the animal from sinking and drowning. In addition, the eye contralateral to the active hemisphere remains open.

Some birds (for example, mallard ducks) can also sleep with only one hemisphere, keeping the opposite eye open to watch for predators (Rattenborg, Lima, and Amlaner, 1999).

- The two hemispheres sleep independently, presumably so that the animal remains behaviorally alert.

Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation studies with human subjects have provided little evidence that sleep is needed to keep the body functioning normally.

The results of sleep deprivation studies suggest that the restorative effects of sleep are more important for the brain than for the rest of the body.

Fatal familial insomnia

- A fatal inherited disorder characterized by progressive insomnia.

- An inherited neurological disorder called fatal familial insomnia results in damage to portions of the thalamus(Sforza et al., 1995; Gallassi et al., 1996; Montagna et al., 2003).

- The symptoms of this disease, which is related to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (“mad cow disease”), include deficits in attention and memory, followed by a dreamlike, confused state; loss of control of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system; and insomnia.

- The first signs of sleep disturbances are reductions in sleep spindles and K complexes. As the disease progresses, slow-wave sleep completely disappears, and only brief episodes of REM sleep (without the accompanying paralysis) remain.

- As the name indicates, the disease is fatal. Whether the insomnia, caused by the brain damage, contributes to the other symptoms and to the patient’s death is not known.

During slow-wave sleep, both cerebral metabolic rate and cerebral blood flow decline, falling to about 75 percent of the waking level during stage 4 sleep (Sakai et al., 1979; Buchsbaum et al., 1989; Maquet, 1995).

In particular, the regions that have the highest levels of activity during waking show the highest levels of delta waves—and the lowest levels of metabolic activity—during slow-wave sleep.

Thus, the presence of slow-wave activity in a particular region of the brain appears to indicate that that region is resting.

As we know from behavioral observation, people are unreactive to all but intense stimuli during slow-wave sleep and, if awakened, act groggy and confused, as if their cerebral cortex has been shut down and has not yet resumed its functioning.

In addition, several studies have shown that missing a single night’s sleep impairs people’s cognitive abilities; presumably, the brain needs sleep to function at peak efficiency(Harrison and Horne, 1998, 1999). These observations suggest that during slow-wave sleep the brain is indeed resting.

2. Functions of REM Sleep

REM sleep is a time of intense physiological activity.

- The eyes dart about rapidly, the heart rate shows sudden accelerations and decelerations, breathing becomes irregular, and the brain becomes more active.

It would be unreasonable to expect that REM sleep has the same functions as slow-wave sleep.

Researchers have long been struck by the fact that the highest proportion of REM sleep is seen during the most active phase of brain development. Perhaps, then, REM sleep plays a role in this process (Siegel, 2005).

Rebound phenomenon

The increased frequency or intensity of a phenomenon after it has been temporarily suppressed; for example, the increase in REM sleep seen after a period of REM sleep deprivation.

But if the function of REM sleep is to promote brain development, why do adults have REM sleep? One possibility is that REM sleep facilitates the massive changes in the brain that occur during development but also some of the more modest changes responsible for learning that occur later in life. Evidence does suggest that REM sleep facilitates learning—but so does slow-wave sleep..

3. Sleep and Learning

Sleep and Learning

Research with both humans and laboratory animals indicates that sleep does more than allow the brain to rest.

Sleep also aids in the consolidation of long-term memories (Marshall and Born 2007).

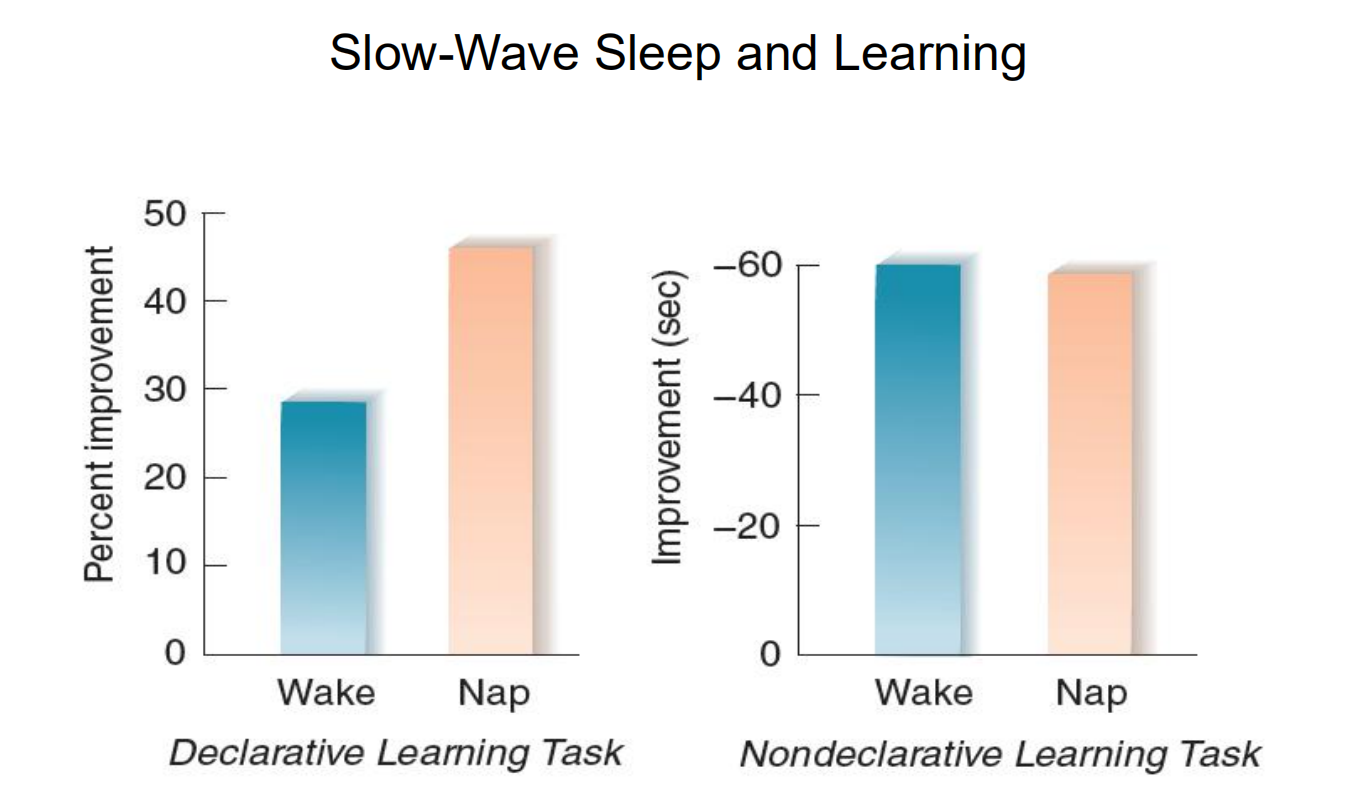

In fact, slow-wave sleep and REM sleep play different roles in memory consolidation.

Two Kinds of Memory

There are two major categories of long-term memory: declarative memory (also called explicit memory) and nondeclarative memory (also called implicit memory).

- Declarative memories include those that people can talk about, such as memories of past episodes in their lives. They also include memories of the relationships between stimuli or events, such as the spatial relationships between landmarks that permit us to navigate around our environment.

- Nondeclarative memories include those gained through experience and practice that do not necessarily involve an attempt to “memorize” information, such as learning to drive a car, throw and catch a ball, or recognize a person’s face. Research has found that slow-wave sleep and REM sleep play different roles in the consolidation of declarative and nondeclarative memories.

During REM sleep, people normally have a high level of consciousness. If we awaken people during REM sleep, they will be alert and clear-headed and will usually be able to describe the details of a dream that they were having.

However, if we awaken people during slow-wave sleep, they will tend to be groggy and confused, and will usually tell us that very little was happening.

So which stages of sleep do you think aid in the consolidation of declarative and nondeclarative memories?

But…

- REM sleep is associated with nondeclarative memories.

- Slow-wave sleep is associated with declarative memories.

Let’s look at evidence from two studies that examined the effects of a nap on memory consolidation. Mednick, Nakayama, and Stickgold (2003) had subjects learn a nondeclarative visual discrimination task at 9:00 a.m.

The subjects’ ability to perform the task was tested ten hours later, at 7:00 p.m. Some, but not all, of the subjects took a ninety-minute nap during the day between training and testing.

The investigators recorded the EEGs of the sleeping subjects to determine which of them engaged in REM sleep and which of them did not. (Obviously, all of them engaged in slow-wave sleep, because this stage of sleep always comes first in healthy people.)

The investigators found that the performance of subjects who did not take a nap was worse when they were tested at 7:00 p.m. than it had been at the end of training.

The subjects who engaged only in slow-wave sleep did about the same during testing as they had done at the end of training.

However, the subjects who engaged in REM sleep performed significantly better. Thus, REM sleep strongly facilitated the consolidation of a nondeclarative memory.

REM Sleep and Learning

- The graph shows the role of REM sleep in learning a nondeclarative visual discrimination task. Only after a ninety-minute nap that included both slow-wave sleep and REM sleep did the subjects’ performance improve.

In the second study, Tucker et al. (2006) trained subjects on two tasks: a declarative task (learning a list of paired words) and a nondeclarative task (learning to trace a pencil-and-paper design while looking at the paper in a mirror). Afterwards, some of the subjects were permitted to take a nap lasting for about one hour. Their EEGs were recorded, and they were awakened before they could engage in REM sleep. The subjects’ performance on the two tasks was then tested six hours after the original training. The investigators found that compared with subjects who stayed awake, a nap consisting of just slow-wave sleep increased the subjects’ performance on the declarative task but had no effect on performance of the nondeclarative task.

So these two experiments (and many others I have not described) indicate that REM sleep facilitates consolidation of nondeclarative memories, and slow-wave sleep facilitates consolidation of declarative memories.

- Subjects learned a declarative learning task (list of paired words) and a nondeclarative learning task (mirror tracing). After a nap that included just slow-wave sleep, only subjects who learned the declarative learning task showed improved performance, compared with subjects who stayed awake.

Slow wave sleep and sharp wave ripple in the hippocampus

- Behavior-dependence of hippocampal LFP activity.

- Top, LFP recorded from symmetric locations of the left (LH) and right (RH) dorsal CA1 str. radiatum during locomotion—immobility transition. Note regular theta waves during locomotion and large amplitude, bilaterally synchronous negative waves (sharp waves, SPW) during immobility. Below, SPWs recorded from str. Radiatum (red) and ripple recorded from the CA1 pyramidal layer. Reproduced from Buzsaki et al. (1992).

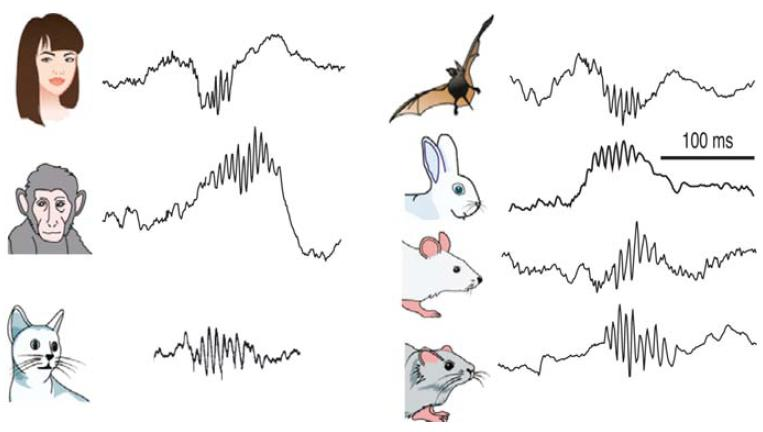

- Preservation of SPW-Rs in mammals. Illustrative traces of ripples recorded from various species. Reproduced from Buzsaki et al., (2013).

二、Physiological Mechanisms of Sleep and Waking

There are two ways human body feels sleepy

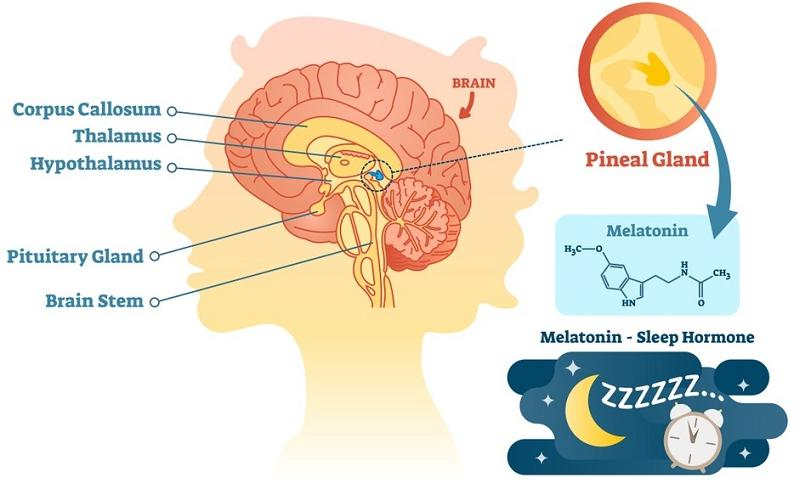

- Circadian rhythm causes secretion of hormone melatonin at certain time of the day (at the onset of darkness). Melatonin tells the body that it is time to rest and sleep. More of this later…

- The chemical adenosine acts as a sleep-inducing (hypnogenic) molecule

Chemical Control of Sleep

Adenosine

- A neuromodulator that is released by neurons engaging in high levels of metabolic activity, may play primary role in the initiation of sleep.

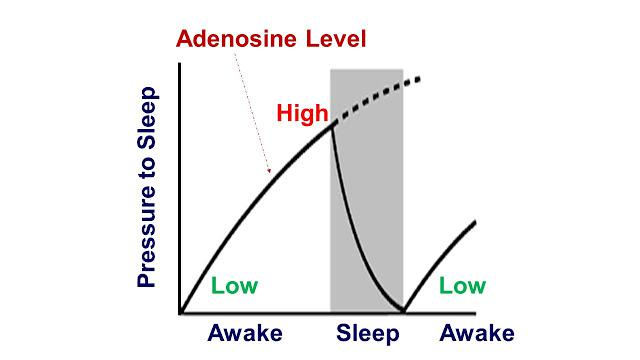

The chemical adenosine acts as a sleep-inducing (hypnogenic) molecule. Adenosine is produced by the break up of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during energy generation to power bodily functions. The activity of the neurons and gilial cells causes a build up of adenosine in the brain and this increases the sleep pressure.

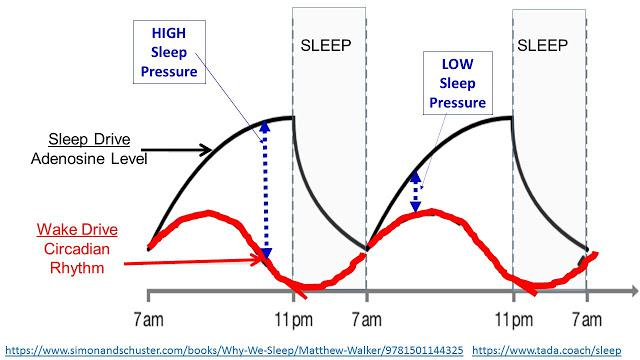

- After 12 to 16 hours of wakefulness, the level of adenosine and hence the sleep pressure reaches a high value and one has a strong desire to sleep. During sleep, adenosine is destroyed and after 8 hours of sleep, adenosine levels reach a low value with a correspondingly weaker sleep pressure. This is shown in the figure:

- Adenosine works by attaching itself to receptor sites in the brain to induce sleep pressure. Substances like caffeine have similar molecular structure to adenosine and are present in tea, coffee, coke and many other food items. Caffeine attaches to adenosine receptors in the brain and prevents the build up of sleep pressure. That is why, it is advisable to avoid caffeine 4 to 5 hours before sleeping time in order to ensure a good night sleep.

As we all know, people differ in their sleep need. Evidence suggests that genetic factors affect the typical duration of a person’s slow-wave sleep. Rétey et al. (2005) discovered one of these factors—variability in the gene that encodes for an enzyme, adenosine deaminase, which is involved in the breakdown of adenosine.

- The investigators found that people with the G/A allele for this gene, which encodes for a form of the enzyme that breaks down adenosine more slowly, spent approximately thirty minutes more time in slow-wave sleep than did people with the more common G/G allele.

Levels of adenosine in people with the G/A allele decreased more slowly during slow-wave sleep, and as a consequence the slow-wave sleep of these people was prolonged.

Neural Control of Arousal

Circuits of neurons that secrete at least five different neurotransmitters play a role in some aspect of an animal’s level of alertness and wakefulness—what is commonly called arousal: acetylcholine, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, and orexin (Wada et al., 1991; McCormick, 1992; Marrocco, Witte, and Davidson, 1994; Hungs and Mignot, 2001).

1. Acetylcholine (ACh)

One of the most important neurotransmitters involved in arousal—especially of cerebral cortex—is acetylcholine.

Two groups of ACh neurons, one in the dorsal pons and one located in the basal forebrain, produce activation and cortical desynchrony when they are stimulated (Jones 1990; Steriade 1996).

- Cape and Jones (2000) found that drugs that activated these neurons caused wakefulness.

- Lee et al. (2004) found that most neurons in the basal forebrain showed a high rate of firing during both waking and REM sleep and a low rate of firing during slow-wave sleep.

- Cholinergic system

- (acetylcholine Active in maintaining waking electro- encephalographic (EEG) patterns of ne neocortex. Thought to play a role in memory by maintaining neuron excitability. Death of acetylcholine neurons and decrease in acetylcholine in the neocortex are thought to be related to Alzheimers disease

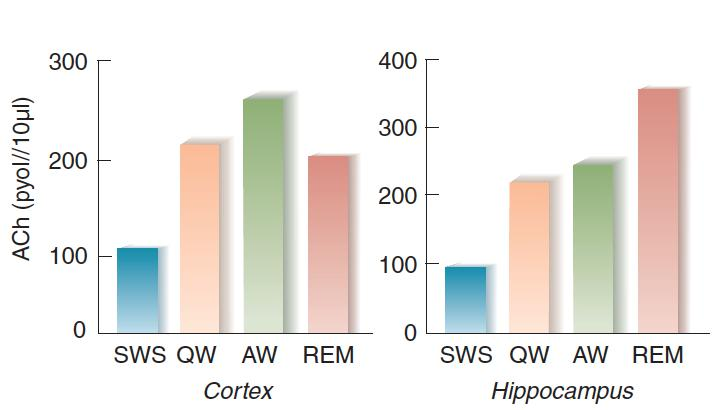

Release of Acetylcholine and the Sleep-Waking Cycle

- The graphs show the release of acetylcholine from the cortex and hippocampus during the sleep-waking cycle. SWS = slow-wave sleep, QW = quiet waking, AW = active waking.

2. Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine

- Investigators have long known that catecholamine agonists such as amphetamine produce arousal and sleeplessness.

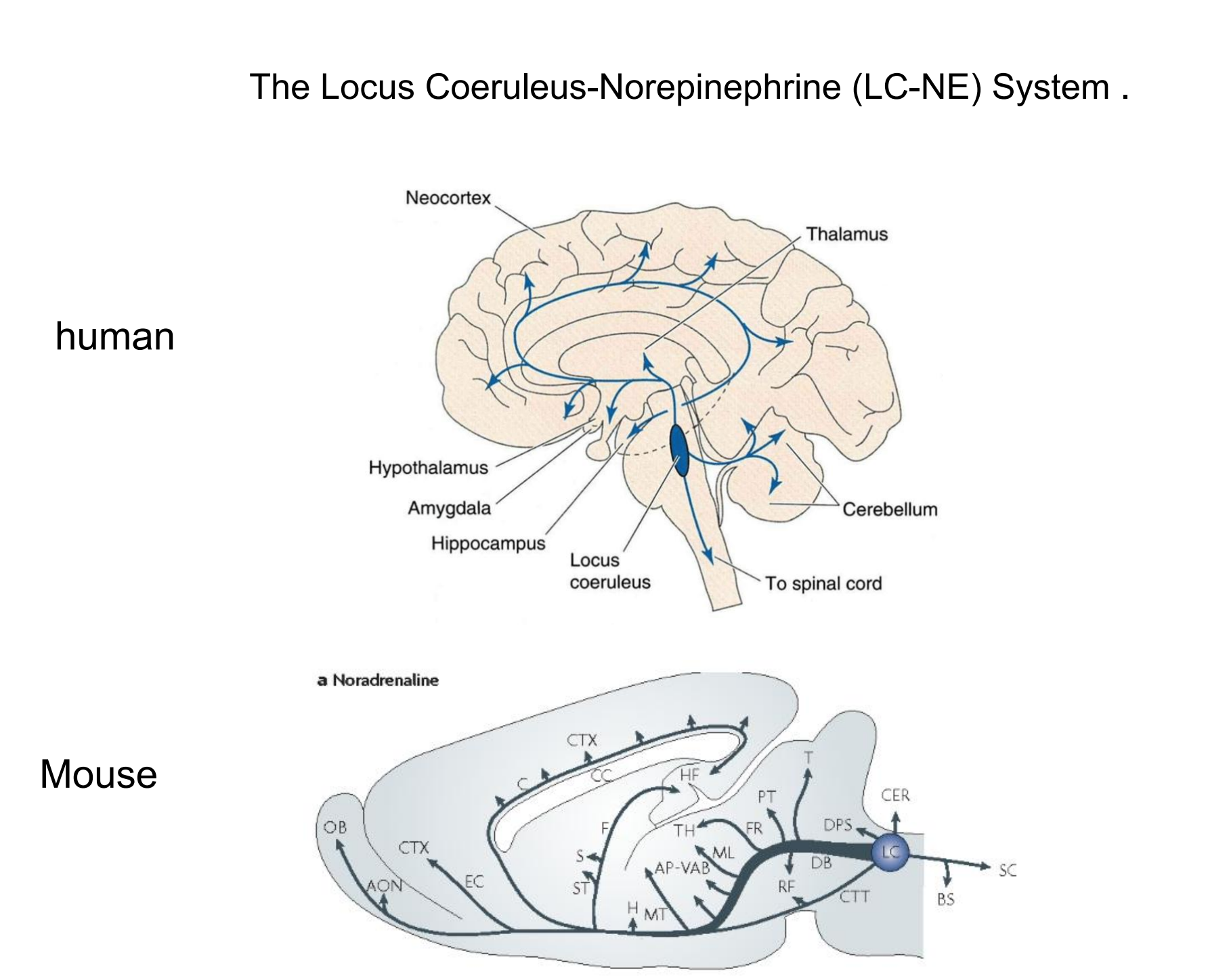

- These effects appear to be mediated primarily by the noradrenergic system of the locus coeruleus, located in the dorsal pons.

Norepinephrine and the Sleep-Waking Cycle

- This graph shows the activity of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus of freely moving rats during various stages of sleep and waking.

3. Locus coeruleus

Locus coeruleus

- A dark-colored group of noradrenergic cell bodies located in the pons near the rostral end of the floor of the fourth ventricle; involved in arousal and vigilance.

In an experiment using optogenetic methods, Carter et al. (2010) found that stimulation of locus coeruleus neurons caused immediate waking, and that inhibition decreased wakefulness and increased slow-wave sleep.

Most investigators believe that activity of noradrenergic LC neurons increases an animal’s vigilance—its ability to pay attention to stimuli in the environment. In fact, a study by Aston-Jones et al. (1994) found that the moment-to-moment activity of noradrenergic LC neurons was directly related to the animals’ current performance on a task that required vigilance

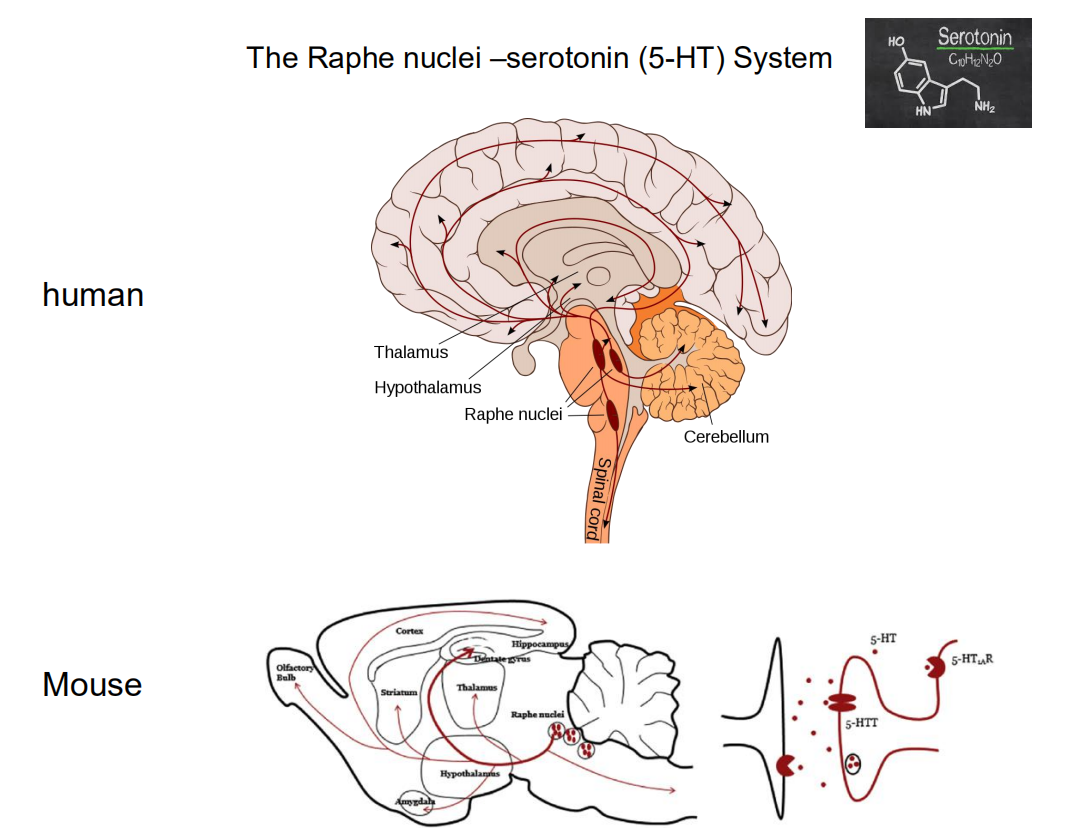

4. Serotonin

Serotonin

- A third neurotransmitter, serotonin (5-HT), also appears to play a role in activating behavior.

- Almost all of the brain’s serotonergic neurons are found in the raphe nuclei, which are located in the medullary and pontine regions of the reticular formation.

Serotonin and the Sleep-Waking Cycle

- This graph shows the activity of serotonergic (5-HT-secreting) neurons in the dorsal raphe nuclei of freely moving cats during various stages of sleep and waking

Raphe nuclei

Raphe nuclei

- A group of nuclei located in the reticular formation of the medulla, pons, and midbrain, situated along the midline; contain serotonergic neurons.

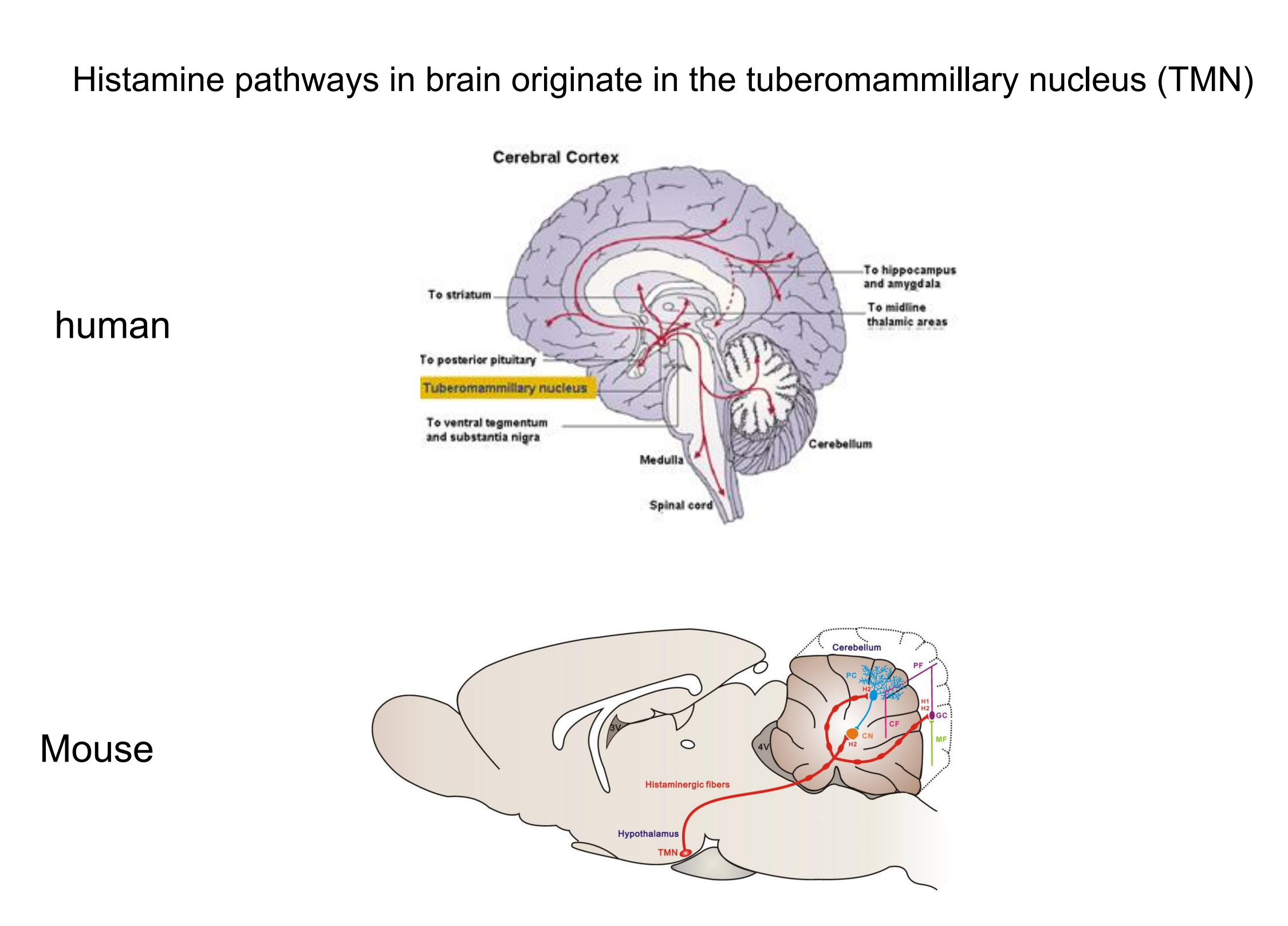

5. Histamine

Histamine

- The fourth neurotransmitter implicated in the control of wakefulness and arousal is histamine, a compound synthesized from histidine, an amino acid.

Histamine pathways in brain originate in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN)

The activity of histaminergic neurons is high during waking but low during slow-wave sleep and REM sleep (Steininger et al., 1996).

In addition, injections of drugs that prevent the synthesis of histamine or block histamine receptors decrease waking and increase sleep (Lin, Sakai, and Jouvet, 1998).

Also, infusion of histamine into the basal forebrain region of rats causes an increase in waking and a decrease in non-REM sleep (Ramesh et al., 2004).

Tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN)

Tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN)

- A nucleus in ventral posterior hypothalamus, just rostral to the mammillary bodies; contains histaminergic neurons involved in cortical activation and behavioral arousal.

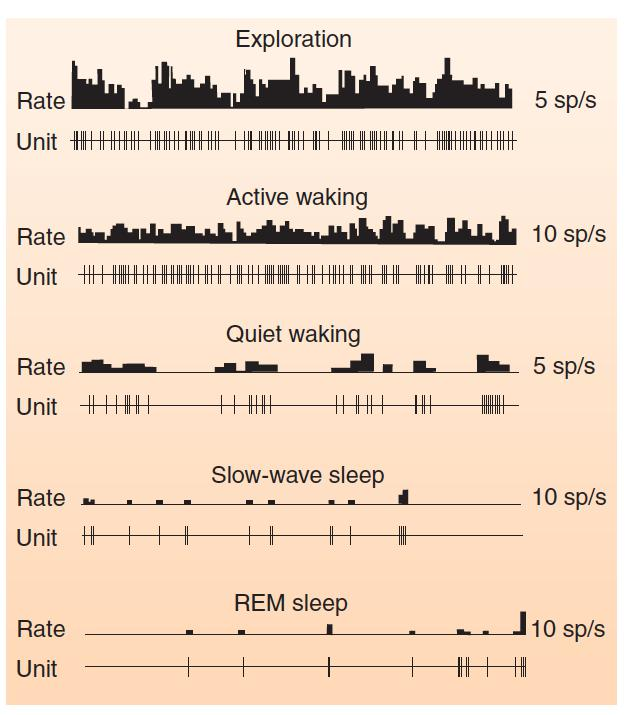

6. Orexin

As we saw in the section on sleep disorders, the cause of narcolepsy is degeneration of orexinergic neurons in humans and a hereditary absence of orexin-B receptors in dogs. The cell bodies of neurons that secrete orexin (as we saw, also called hypocretin) are located in the lateral hypothalamus. Although there are only about 7000 orexinergic neurons in the human brain, the axons of these neurons project to almost every part of the brain, including the cerebral cortex and all of the regions involved in arousal and wakefulness, including the locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, tuberomammillary nucleus, and acetylcholinergic neurons in the dorsal pons and basal forebrain (Sakurai, 2007). Orexin has an excitatory effect in all of these regions.

As we saw earlier, narcolepsy is most often treated with modafinil, a drug that suppresses the drowsiness associated with this disorder. Ishizuka, Murotani, and Yamatodani (2010) found that the modafinil produces its alerting effects by stimulating the release of orexin in the TMN, which activates the histaminergic neurons located there.

Orexinergic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus:

Mileykovskiy, Kiyashchenko, and Siegel (2005) recorded the activity of single orexinergic neurons in unanesthetized rats and found that the neurons fired at a high rate during alert or active waking, and at a low rate during quiet waking, slow-wave sleep, and REM sleep.

The highest rate of firing was seen when the rats were engaged in exploratory activity.

Adamantidis, Carter, and de Lecea (2010) used optogenetic methods to activate neurons in the lateral hypothalamus of mice, and found that this activation awakened the animals from either REM or non-REM sleep.

Orexin and the Sleep-Waking Cycle

- This graph shows the activity of single hypocretinergic neurons during various stages of sleep and waking.

Neural Control of Slow-Wave Sleep

Sleep is controlled by three factors: homeostatic, allostatic, and circadian.

If we go without sleep for a long time, we will eventually become sleepy, and once we sleep, we will be likely to sleep longer than usual and make up at least some of our sleep debt. This control of sleep is homeostatic in nature.

But under some conditions, it is important for us to stay awake—for example, when we are being threatened by a dangerous situation or when we are dehydrated and are looking for some water to drink. This control of sleep is allostatic in nature, and refers to reactions to stressful events in the environment (danger, lack of water, etc.) that serve to override homeostatic control.

Finally, circadian factors, or time of day factors, tend to restrict our period of sleep to a particular portion of the day/night cycle.

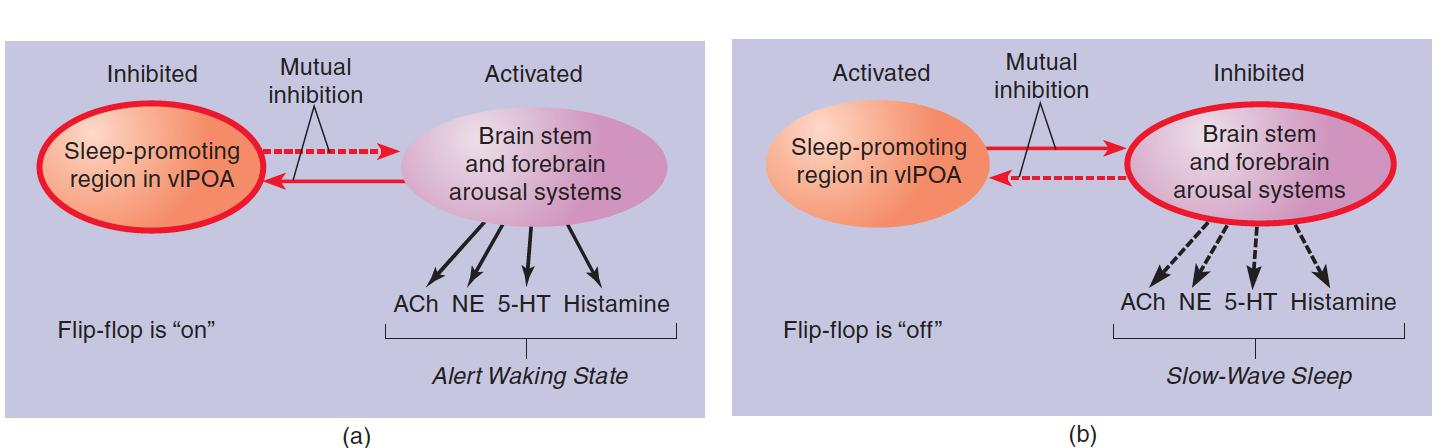

- But what controls the activity of the arousal neurons? What causes this activity to fall, thus putting us to sleep? The preoptic area , a region of the anterior hypothalamus, is the brain region most involved in the initiation of sleep. The preoptic area contains neurons whose axons form inhibitory synaptic connections with the brain’s arousal neurons. When our preoptic neurons (let’s call them sleep neurons) become active, they suppress the activity of our arousal neurons, and we fall asleep (Saper, Scammell, and Lu, 2005).

Ventrolateral preoptic area (vlPOA)

Ventrolateral preoptic area (vlPOA)

- Group of GABAergic neurons in the preoptic area whose activity suppresses alertness and behavioral arousal and promotes sleep.

The majority of the sleep neurons are located in the ventrolateral preoptic area (vlPOA) .

Damage to vlPOA neurons suppresses sleep (Lu et al., 2000), and the activity of these neurons, measured by their levels of Fos protein, increases during sleep.

Experiments have shown that the sleep neurons secrete the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, and that they send their axons to the five brain regions involved in arousal described in the previous section (Sherin et al., 1998; Gvilia et al., 2006; Suntsova et al., 2007).

As we saw, activity of neurons in these five regions causes cortical activation and behavioral arousal. Inhibition of these regions, then, is a necessary condition for sleep.

The sleep neurons in the vlPOA receive inhibitory inputs from some of the same regions they inhibit, including the tuberomammillary nucleus, raphe nuclei, and locus coeruleus (Chou et al., 2002).

As Saper and his colleagues (2001, 2010) suggest, this mutual inhibition may provide the basis for establishing periods of sleep and waking.

They note that reciprocal inhibition also characterizes an electronic circuit known as a flip-flop. A flip-flop can assume one of two states, usually referred to as on or off—or 0 or 1 in computer applications. Thus, either the sleep neurons are active and inhibit the wakefulness neurons or the wakefulness neurons are active and inhibit the sleep neurons.

Because these regions are mutually inhibitory, it is impossible for neurons in both sets of regions to be active at the same time. In fact, sleep neurons in the vlPOA are silent until an animal shows a transition from waking to sleep (Takahashi, Lin, and Sakai, 2009).

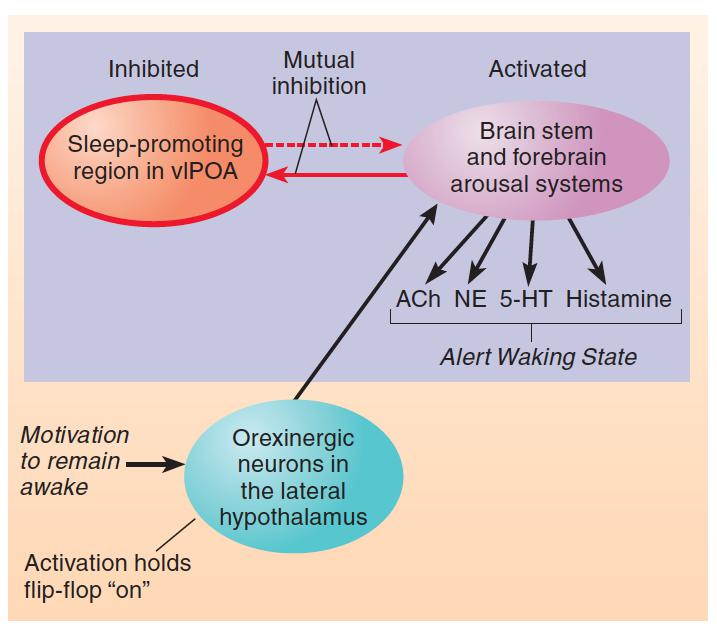

The Sleep/Waking Flip-Flop

According to Saper et al. (2001), the major sleep-promoting region (the vlPOA) and the major wakefulness-promoting regions (basal forebrain and pontine regions that contain acetylcholinergic neurons; the locus coeruleus, which contains noradrenergic neurons; the raphe nuclei, which contain serotonergic neurons; and the tuberomammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus, which contains histaminergic neurons) are reciprocally connected by inhibitory GABAergic neurons. (a) When the flip-flop is in the “wake” state, the arousal systems are active, the vlPOA is inhibited, and the animal is awake. (b) When the flip-flop is in the “sleep” state, the vlPOA is active, the arousal systems are inhibited, and the animal is asleep.

A flip-flop has an important advantage: When it switches from one state to the other, it does so quickly. Clearly, it is most advantageous to be either asleep or awake; a state that has some of the characteristics of both sleep and wakefulness would be maladaptive.

- However, there is one problem with flip-flops: They can be unstable. In fact, people with narcolepsy and animals with damage to the orexinergic system of neurons exhibit just this characteristic. They have great difficulty remaining awake when nothing interesting is happening, and they have trouble remaining asleep for an extended amount of time

Saper et al. (2001, 2010) suggest that an important function of orexinergic neurons is to help stabilize the sleep/waking flip-flop through their excitatory connections to the wakefulness neurons. Activity of this system of neurons tips the activity of the flip-flop toward the waking state, thus promoting wakefulness and inhibiting sleep. Perhaps your success at staying awake during a boring lecture depends on maintaining a high rate of firing of your orexinergic neurons, which would keep the flip-flop in the waking state. A mathematical model of the sleep/waking flip-flop constructed by Rempe, Best, and Terman (2010) confirmed the role of orexigenic neurons in stabilizing the circuit.

Role of Orexinergic Neurons in Sleep

- The schematic diagram shows the effect of activation of the orexinergic system of neurons of the lateral hypothalamus on the sleep/waking flip-flop. Motivation to remain awake or events that disturb sleep activate the orexinergic neurons.

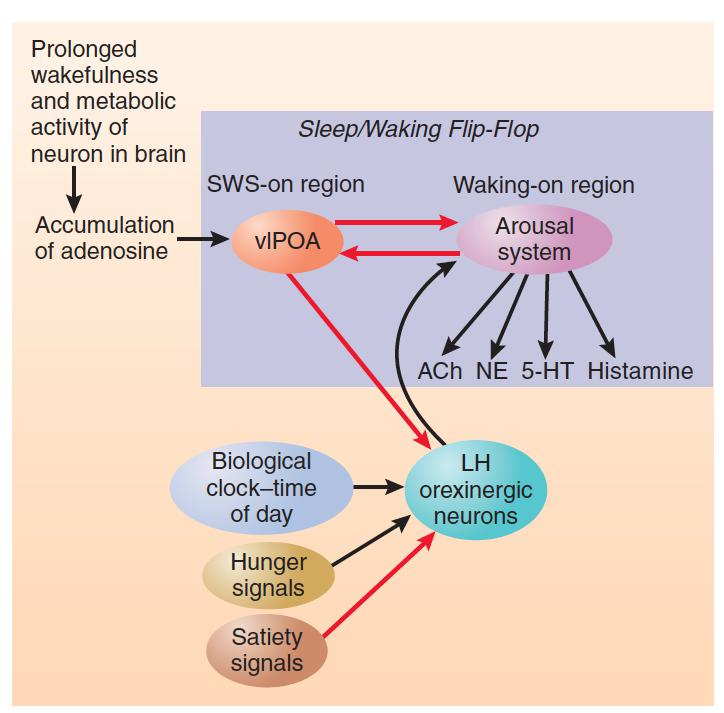

Seeing that orexinergic neurons help hold the sleep/waking flip-flop in the waking state, the obvious question to ask is what factors control the activity of orexinergic neurons?

During the waking part of the day/night cycle, orexinergic neurons receive an excitatory signal from the biological clock that controls daily rhythms of sleep and waking.

These neurons also receive signals from brain mechanisms that monitor the animal’s nutritional state: Hunger-related signals activate orexinergic neurons, and satiety-related signals inhibit them. Thus, orexinergic neurons maintain arousal during the times that an animal should search for food. In fact, if normal mice (but not mice with a targeted mutation against orexin receptors) are given less food than they would normally eat, they stay awake longer each day (Yamanaka et al., 2003; Sakurai, 2007).

Finally, orexinergic neurons receive inhibitory input from the vlPOA, which means that sleep signals that arise from the accumulation of adenosine can eventually overcome excitatory input to orexinergic neurons and sleep can occur.

Adenosine, Time of Day, and Hunger

- This figure shows the role of adenosine, time of day, and hunger and satiety signal son the sleep/waking flip-flop

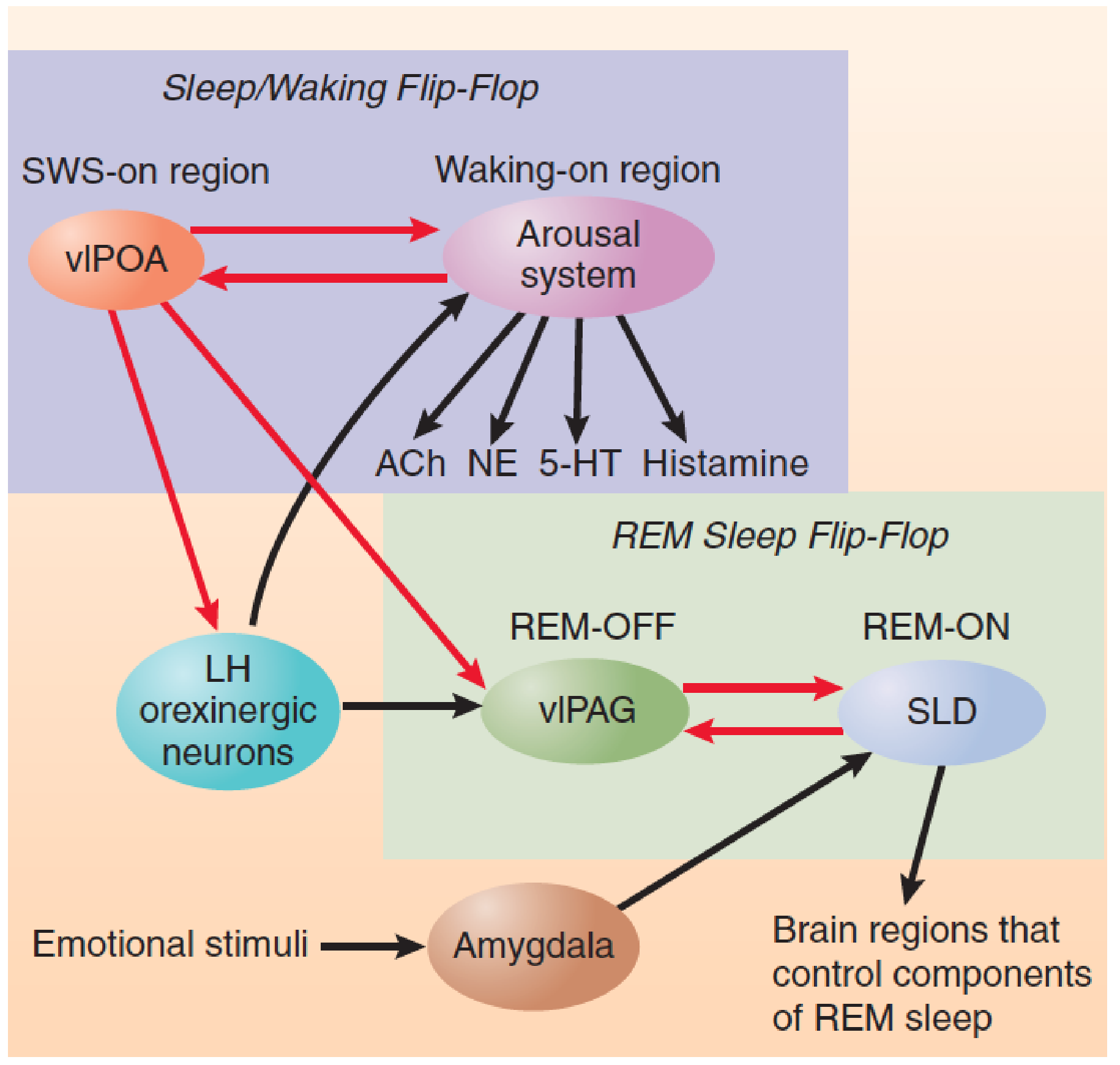

Neural Control of REM Sleep

As we shall see, REM sleep is controlled by a flip-flop similar to the one that controls cycles of sleep and waking.

The sleep/waking flip-flop determines when we wake and when we sleep, and once we fall asleep REM flip-flop controls our cycles of REM sleep and slow-wave sleep.

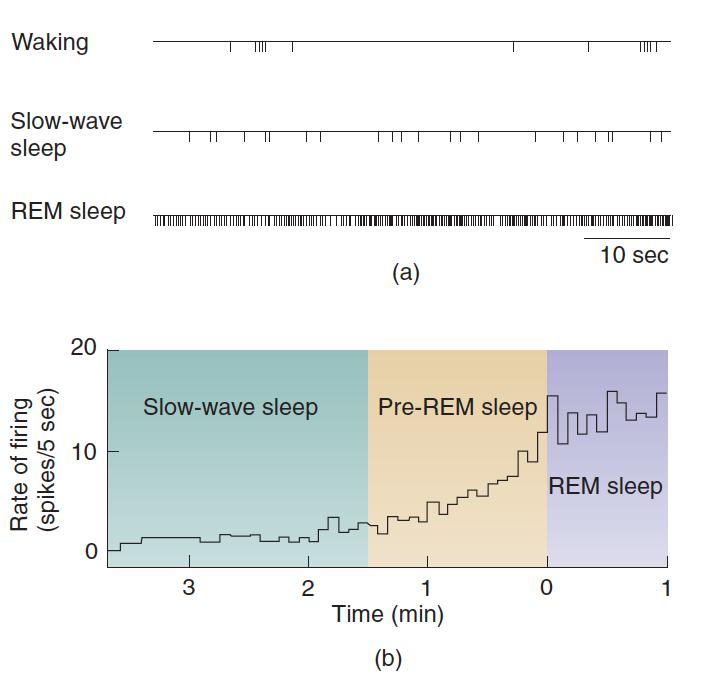

1. REM Flip-Flop

As seen earlier in this chapter, acetylcholinergic neurons play an important role in cerebral activation during alert wakefulness.

Researchers have also found that they are involved in the neocortical activation that accompanies REM sleep.

ACh neurons in the dorsal pons fire at a high rate during both REM sleep and active wakefulness or during REM sleep alone.

Firing Pattern of a REM-ON Cell:

- The acetylcholinergic REM-ON cell is located in the dorsal pons. The figure shows (a) action potentials during sixty-minute intervals during waking, slow-wave sleep, and REM sleep, and (b) the rate of firing just before and after the transition from slow-wave sleep to REM sleep. The increase inactivity begins approximately 80 seconds before the onset of REM sleep.

Sublaterodorsal nucleus (SLD)

Sublaterodorsal nucleus (SLD)

- A region of dorsal pons, just ventral to the locus coeruleus, that forms the REM-ON portion of REM sleep flip-flop.

Ventrolateral periaqueductal gray matter (vlPAG)

A region of dorsal midbrain that forms the REM-OFF portion of the REM sleep flip-flop.

The REM-ON and REM-OFF regions are interconnected by means of inhibitory GABAergic neurons.

Stimulation of the REM-ON region with infusions of glutamate agonists elicits most of the elements of REM sleep, whereas inhibition of this region with GABA agonists disrupts REM sleep.

Stimulation of the REM-OFF region suppresses REM sleep, whereas damage to this region or infusion of GABA agonists dramatically increases REM sleep.

The REM Sleep Flip-Flop

- The illustration shows the sequence of events associated with REM sleep flip-flop.

REM Sleep

- This schematic diagram shows the interaction between the sleep/waking flip-flop and the REM sleep flip-flop.

三、Biological Clocks

Circadian Rhythms and Zeitgebers

Circadian rhythm

- A daily rhythmical change in behavior or physiological process.

Daily rhythms in behavior and physiological processes are found throughout the plant and animal world. These cycles are generally called circadian rhythms . (Circa means “about,” and dies means “day”; therefore, a circadian rhythm is one with a cycle of approximately twenty-four hours.)

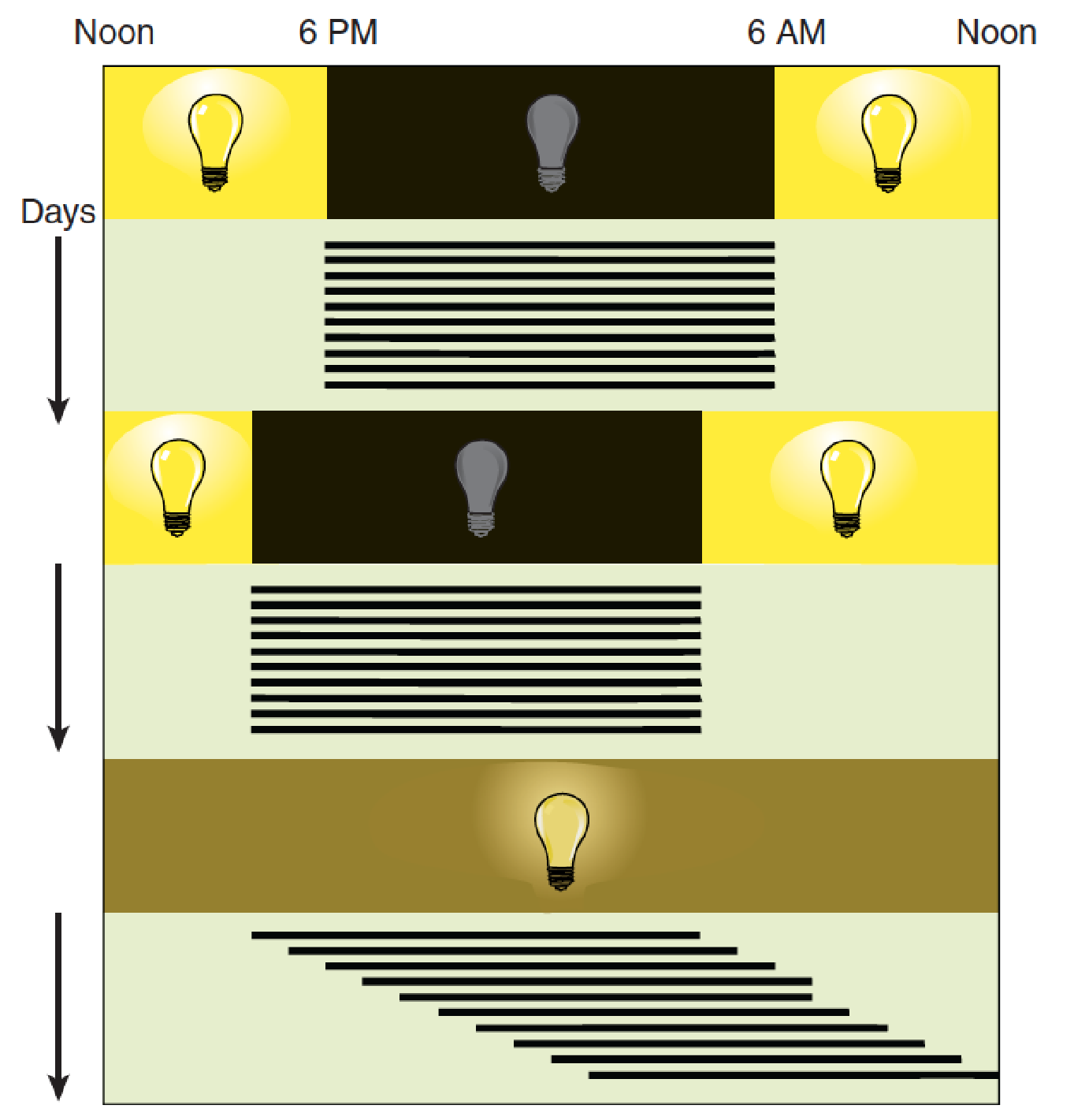

Circadian Rhythms of Wheel-Running Activity of a Rat

- Top: The animal’s activity occurs at “night” (that is, during the twelve hours the light is off). Middle: The period of waking follows the new dark period when the light cycle is changed. Bottom: When the animal is maintained in constant dim illumination, it displays a free-running activity cycle of approximately twenty-five hours, which means that its period of waking begins about one hour later each day.

1. Zeitgeber

Zeitgeber

- A stimulus (usually the light of dawn) that resets the biological clock that is responsible for circadian rhythms.

A free-running clock, with a cycle of approximately twenty-five hours, controls some biological functions—in this case, sleep and wakefulness. Regular daily variation in the level of illumination (that is, sunlight and darkness) normally keeps the clock adjusted to twenty-four hours. Light serves as a zeitgeber (German for “time giver”); it synchronizes the endogenous rhythm.

Studies with many species of animals have shown that if they are maintained in constant darkness (or constant dim light), a brief period of bright light will reset their internal clock, advancing or retarding it, depending upon when the light flash occurs(Aschoff, 1979).

For example, if an animal is exposed to bright light soon after dusk, the biological clock is set back to an earlier time—as if dusk had not yet arrived. On the other hand, if the light occurs late at night, the biological clock is set ahead to a later time—as if dawn had already come.

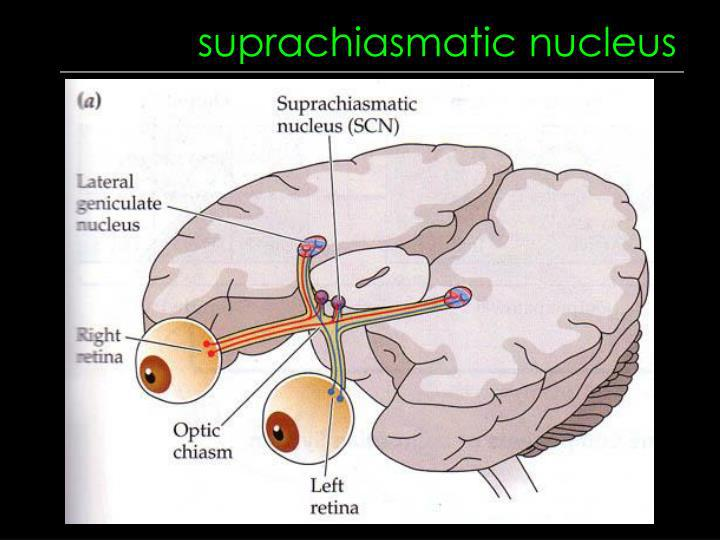

The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus

Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)

- A nucleus situated atop the optic chiasm; It contains a biological clock that is responsible for organizing many of the body’s circadian rhythms.

- The figure shows the location and appearance of the suprachiasmatic nuclei in a rat. Cresyl violet stain was used to color the nuclei in this cross section of a rat brain.

1. Melanopsin

Melanopsin

- A photopigment present in ganglion cells in the retina whose axons transmit information to the SCN, thalamus, and the olivary pretectal nuclei.

Ganglion cells ordinarily receive information about light from the receptors, but about 1% of ganglion cells respond to light directly and send neurons into the retinohypothalamic pathway These ganglion cells contain melanopsin, which is a light-sensitive substance, or photopigment The melanopsin is located in their widely branching dendrites, which suits the cells for detecting the overall level of light, as opposed to contributing to image formation.

A study has confirmed that human retinas have melanopsin in some of their ganglion cells (Dkhissi-Benyahya, Rieux,Hut, & Cooper, 2006).

Melanopsin-Containing Ganglion Cells in the Retina

- The axons of the ganglion cells form the retinohypothalamic tract. These neurons detect the light of dawn that resets the biological clock in the SCN.

2. SCN controls cycles of sleep and waking

Evidence indicates that SCN controls cycles of sleep and waking by two means:

- Direct neural connections.

- The secretion of chemicals that affect the activity of neurons in other regions of the brain.

Multisynaptic pathways are found from the SCN to the subparaventricular zone (SPZ), to the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH) and then to regions involved in the control of sleep and waking, such as the vlPOA and the orexinergic neurons of the lateral hypothalamus.

The projections to the vlPOA are inhibitory and inhibit sleep, whereas the projections to the orexinergic neurons are excitatory and promote wakefulness.

The activity of these connections varies across the day/night cycle. In diurnal animals the activity of these connections are high during the day and low during the night.

Control of Circadian Rhythms

- The SCN controls circadian rhythms in sleep and waking. During the day cycle, the DMH inhibits the vlPOA and excites the brain stem and forebrain arousal systems, thus stimulating wakefulness.

Nature of the Clock

Several studies have demonstrated daily activity rhythms in the SCN, which indicates that the circadian clock is located there.

A study by Schwartz and Gainer (1977) nicely demonstrated day–night fluctuations in the activity of the SCN.

Circadian Activity Rhythms in the SCN

- The autoradiographs show cross sections through the brains of rats that had been injected with carbon 14-labeled 2-deoxyglucose during the day (top) and the night (bottom). The dark region at the base of the brain (arrows) indicates increased metabolic activity of the suprachiasmatic nuclei.

What causes SCN neurons to “tick”?

For many years investigators have believed that circadian rhythms were produced by the production of a protein that, when it reached a certain level in the cell, inhibited its own production.

As a result, levels of the protein would begin to decline, which would remove the inhibition, starting the production cycle again.

Changes in Circadian Rhythms: Shift Work and Jet Lag

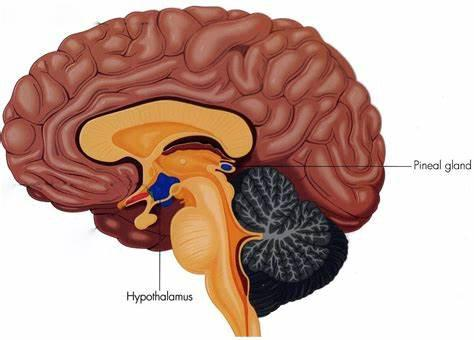

Pineal gland

- A gland attached to the dorsal tectum; produces melatonin and plays a role in circadian and seasonal rhythms.

Melatonin

- A hormone secreted during the night by the pineal body; plays a role in circadian and seasonal rhythms.

The SCN regulates the pineal gland’s secretion of melatonin.

Advanced sleep phase syndrome

- A 4-hour advance in rhythms of sleep and temperature cycles, apparently caused by a mutation of a gene (per2) involved in the rhythmicity of neurons of the SCN.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

- A 4-hour delay in rhythms of sleep and temperature cycles, possibly caused by a mutation of a gene (per3) involved in the rhythmicity of neurons of the SCN.

ineal gland

Summary