L7 Metabolism

一、Why do animals need energy?

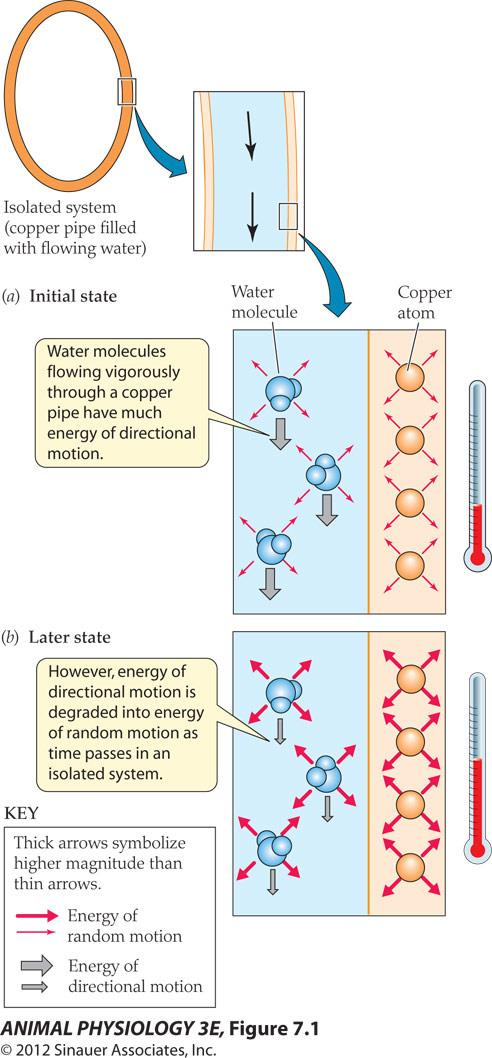

The second law of thermodynamics states that the entropy ( 熵 热 力 学 ) of an isolated system never decreases, because isolated systems always evolve toward thermodynamic equilibrium, a state with maximum entropy.

- Entropy = disorder

热力学第二定律(英文:the second law of thermodynamics)是热力学的四条基本定律之一,表述热力学过程的不可逆性——孤立系统自发地朝着热力学平衡方向──最大熵状态──演化,同样地,第二类永动机永不可能实现。

Entropy, the measure of a system’s thermal energy per unit temperature that is unavailable for doing useful work. Because work is obtained from ordered molecular motion, the amount of entropy is also a measure of the molecular disorder, or randomness, of a system.

- The energy of directional motion of the water molecules is gradually transformed into energy of random motion.

- Over time, the rate of flow of water around the loop of pipe decreases as the energy of directional motion is lost.

- A gradual increase in the energy of random molecular agitation (heat) occurs, and the temperature Increases.

The second law of thermodynamics in action:

- The only way to keep the water flowing and maintain the original order in the water-filled loop of pipe would be to convert the system into an open system.

- The energy put into the system could create order in the system as rapidly as the order in the system diminishes.

- Without energy input, the blood coursing though the animal’s circulatory system will slow to a halt

- The loss of order will eventually kill the animal because order is essential for life.

- Animals require energy from the outside because energy is necessary to create and maintain their essential internal organization.

Four forms of energy

Chemical energy: chemical-bond energy

Electrical energy: cell membranes possess electrical energy because there is a charge separation across them

Mechanical energy: energy of organized motion, such as the motion of an arm, circulating blood

Molecular kinetic energy (heat): the energy of random atomic molecular motion

1. The forms of energy vary in their capacity for physiological work

Physiological work – is any process carried out by an animal that increases order.

For example:

- protein synthesis;

- generate electrical or chemical gradients across cell membrane

- muscle contraction

Chemical energy can be used for all forms of physiological work(totipotent:toti: all, potent: powerful,全能);

Electrical and mechanical energy are not totipotent(i.e. move ions across membrane and pump blood, but not make new proteins)

Animals can not use heat to do any form of physiological work (according to thermodynamics, a system can not convert heat to work only if there is a temperature difference between one part of the system and another.

- High grade energy (can do physiological work)

- Low grade energy (heat, cannot do physiological work)

Animal degrade energy = they transform energy from high grade form to heat!

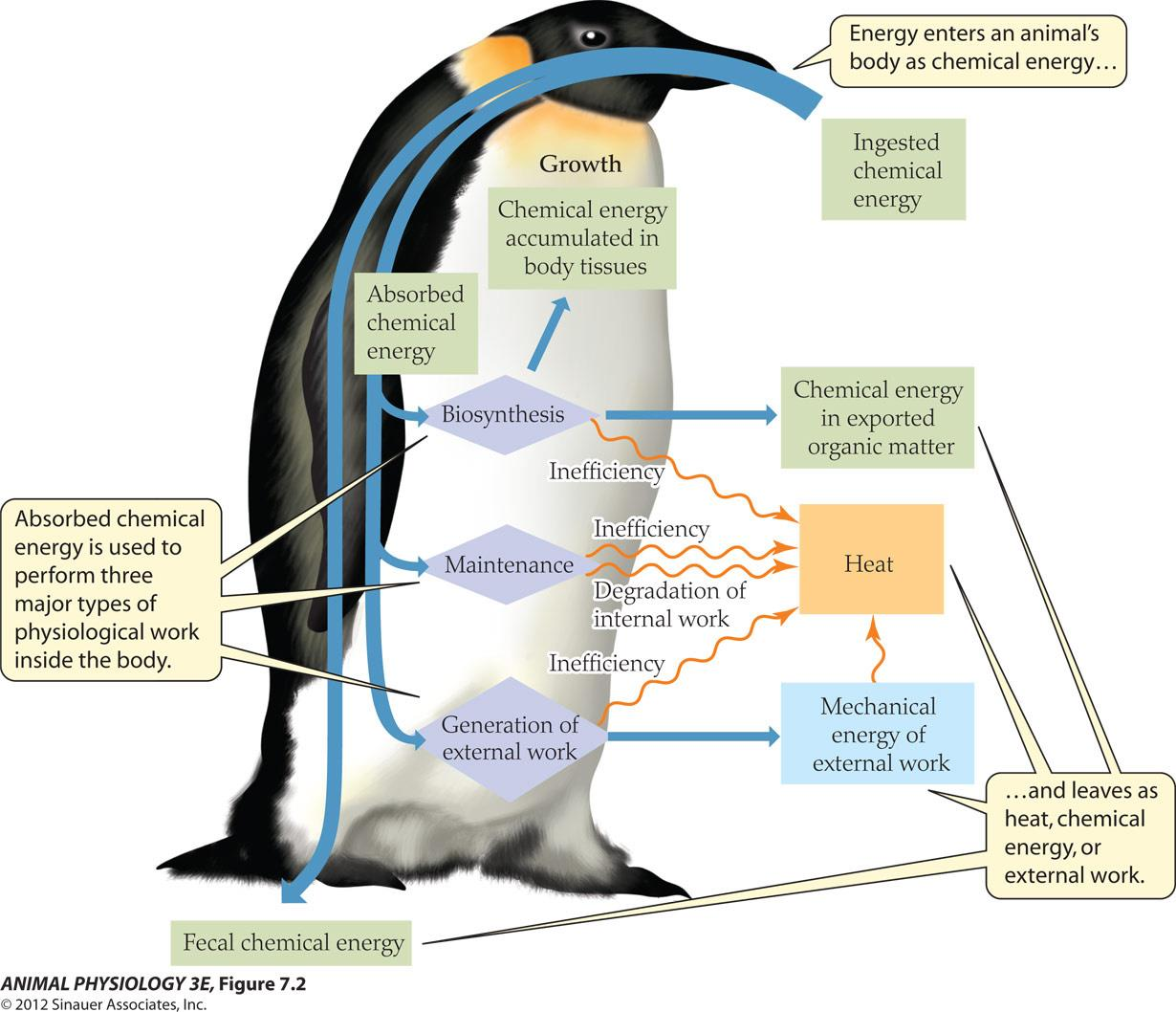

Transformations of high-grade energy are always inefficient

- Efficiency of energy transformation is always inefficient and some energy is degraded into heat

- For example, the efficiency is typically less than 1.

- When cell converts all chemical bond energy of glucose into chemical bond of ATP, Only 70% of the energy is incorporated into bonds of ATP, the other 30% of high grade energy is transformed to low grade energy (heat).

- Riding a bike exercise, the efficiency of leg muscles in producing external motion might be as high as 25-30%. The other 70% of the energy liberated from ATP in the process would become heat.

2. Animals use energy to perform three major functions

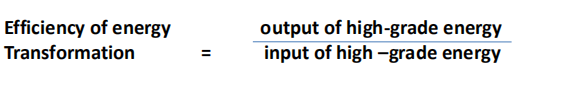

Food provides ingested CHEMICAL energy (or ingested energy), which becomes:

- Fecal chemical energy (fecal energy)

- Absorbed chemical energy (absorbed energy)

An animal uses its absorbed chemical energy to carry out three major types of Physiological work

- Biosynthesis

- Maintenance

- Generation of external work

All living animals produce heat: frogs, fish are cool to the touch, does not mean they do not produce heat. Because they produce little heat and poor insulation to keep the heat.

二、Metabolic rate: meaning and measurement

Physiologist defines consumed energy as energy spent: heat and external work

The rate at which an animal consumes energy is its metabolic rate, that is Animal converts chemical energy to heat and external work. (generally, metabolic rate meant rate of heat production.)

How much to pack in an polar expedition?

The significance of knowing metabolic rates:

- To determine how much food it needs

- Provides a quantitative measure of the total activity of all its physiological mechanisms (an animal’s metabolic rate represents the animal’s intensity of living.)

- Ecologically, metabolic rate measures the drain of the animal places on the physiologically useful energy supplies of its ecosystem.

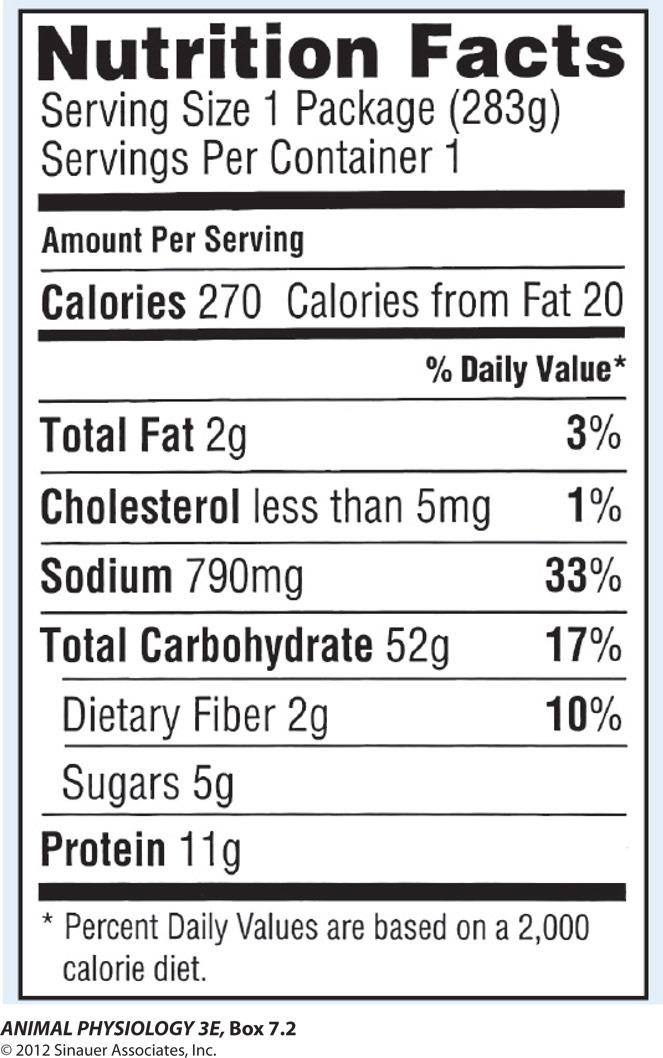

Units of Measure for Energy and Metabolic Rates

1. Units

Energy is measured in calories or joules

(1 cal = the amount of heat needed to raise 1 g of water by 1 °C.)

- 1 kilocalories (kcal) is 1000 cal.

2. Metabolic Rates

Metabolic rates are expressed in calories per unit of time or watts (W).

- 1 Watt = 1 joule / second (J/s)

Measure for Energy in International system of units is the joule (James Joule)

How to convert from joules to calories

- 1 J = 0.239 cal;

How to measure energy used

Direct calorimetry (measure the rate of heat leaves an animal’s body)

Indirect calorimetry (cheaper than direct method)

- Based on respiratory gas exchange

- Indirect calorimetry based on respiratory gas exchange: oxygen consumption is a convenient and readily measured estimate of its metabolic rate.

- Based on material balance (measuring the chemical energy content of the organic matter that enters and leaves the body. Organic materials.)

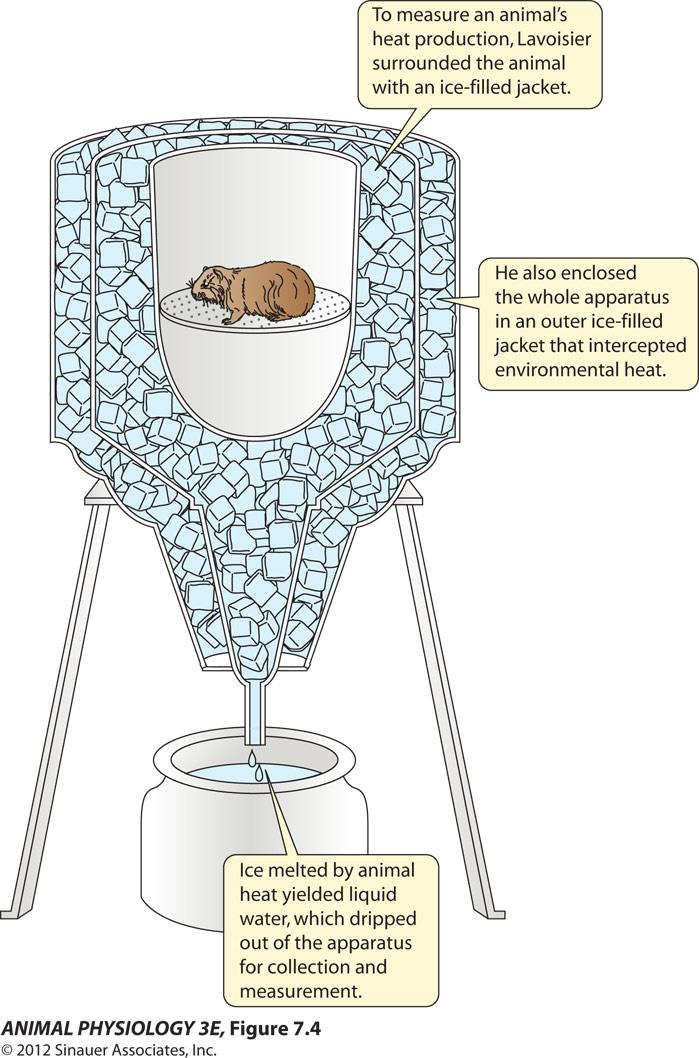

Lavoisier’s direct calorimeter 拉瓦锡直接量热仪 - Direct calorimetry

Indirect Measurement - Gas exchange:

1 mol of Glucose (C6H12O6) is burned completely, 6 mol of O2 will be used (based on chemical stoichiometry). This will release heat known as heat of combustion.

The heat combustion will produce 2820 kilojoules per mole (kJ/mol) or 673000 cal/mol

- C

6H12O6+ 6O2$\rarr$ 6CO2+ 6 H2O + 2820 kJ/mol - A fixed proportional relation exists between heat production and CO2 production

- Therefore oxidize unknown amount of glucose (in a test tube), you only measure the amount of O2 used or the amount of CO2 produced, you can calculate the amount of heat produced.

Calculate metabolic rate

An animal consumes O2 at a rate of 10 mL/min, If animal cells only oxidize glucose, The metabolic rate would be 10 mL O2/min X 21.1 J/ml O2 = 211 J/min

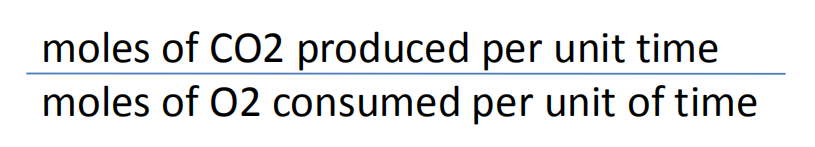

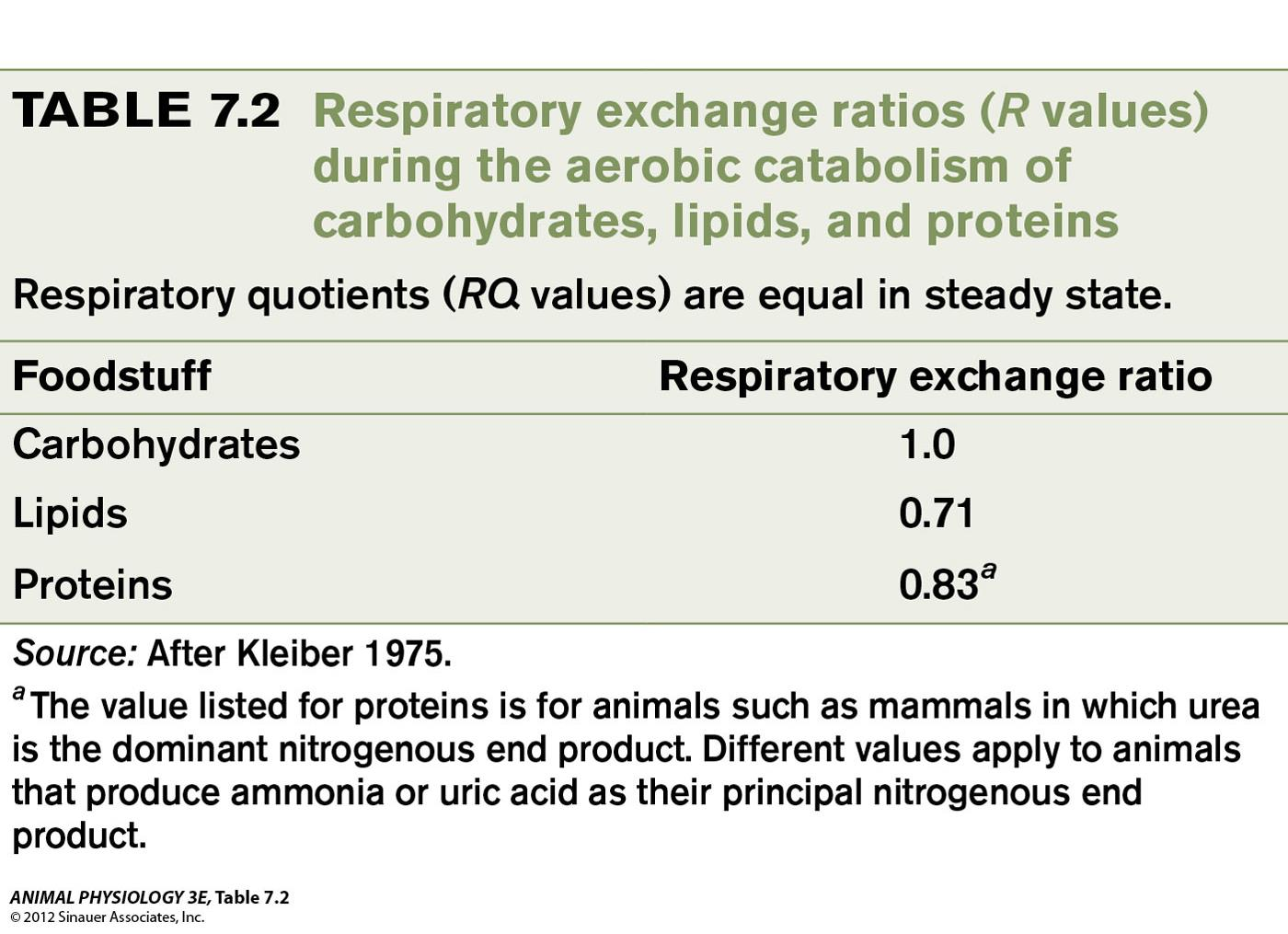

(1) Respiratory exchange ratio [Respiratory quotient (RQ)]

From Table 7.1 it is obvious that the numbers are not simple and fixed numbers.

Animals often oxidize a variety of foodstuffs which yield different quantities of heat per Unit of volume of O2 consumed or CO2 produced.

So indices are needed: Respiratory exchange ratio R, or respiratory quotient (RQ)

- The value of R (respiratory organ) and RQ (at cell level) is a metabolic signature that reveals the particular sorts of foodstuffs being oxidized by an animal’s cells.

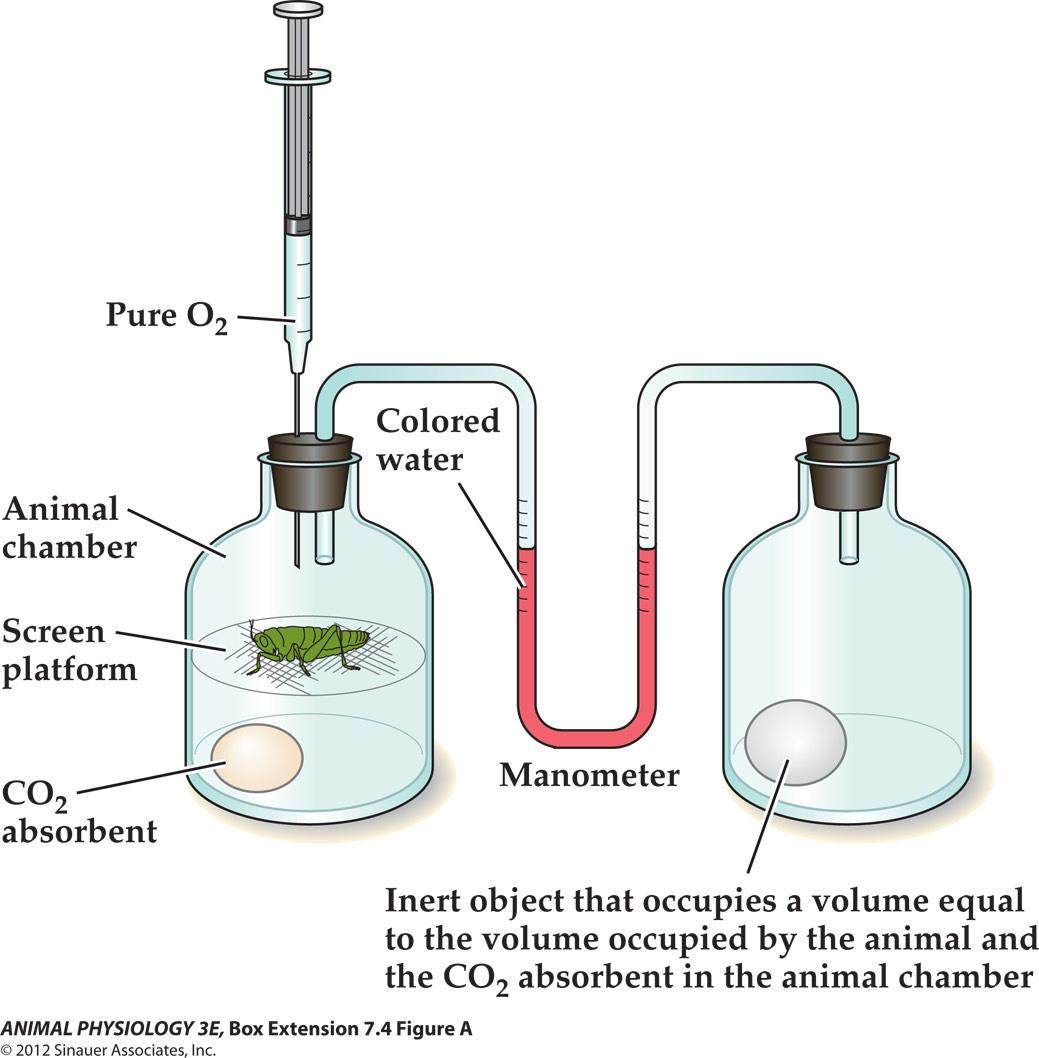

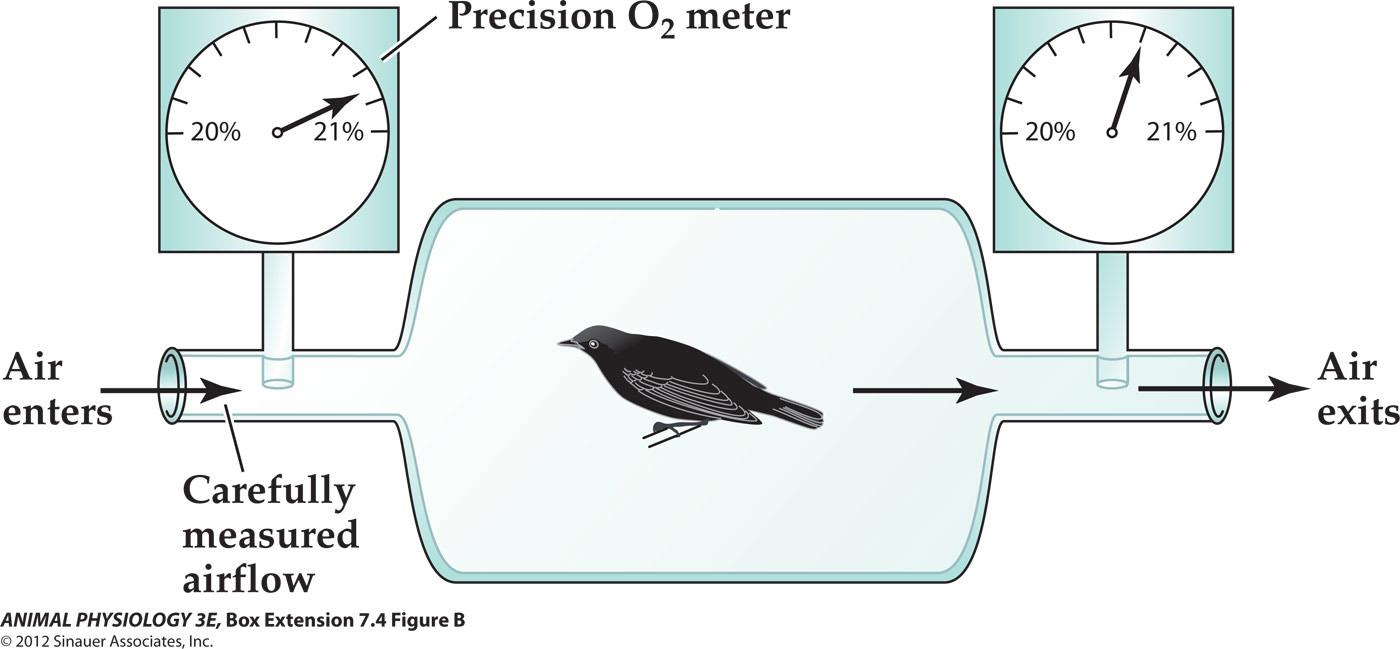

(2) Respirometry - 呼吸测量法

Respirometry is the process of measuring an animal’s gas exchange with its environment. The devices used are called respirometers. For studies of metabolic rate, the most common type of respirometer is the measurement of an animal’s rate of O2 consumption.

In Box Extension 7.4, we offer illustrations and explanations of the two basic types of respirometry configurations that are used to measure O2 consumption: (1) closed configurations, in which an animal is housed in a fully sealed chamber with a relative fixed volume of nonmoving air and (2) open configurations, in which air flows through the animal chamber during measurement.

3. Summary

Metabolic Rate**: **Meaning and Measurement

Metabolic rate Metabolic rate is the rate at which an animal converts chemical energy into heat and external work.

Why Metabolic rate is important?

- It helps to determine the amount of food animals need

- Provides a quantitative measure of the total activity of all its physiology mechanisms.

The most common measure of metabolic rate:

- O2 consumption; (apart from direct calorimetry and material balance)

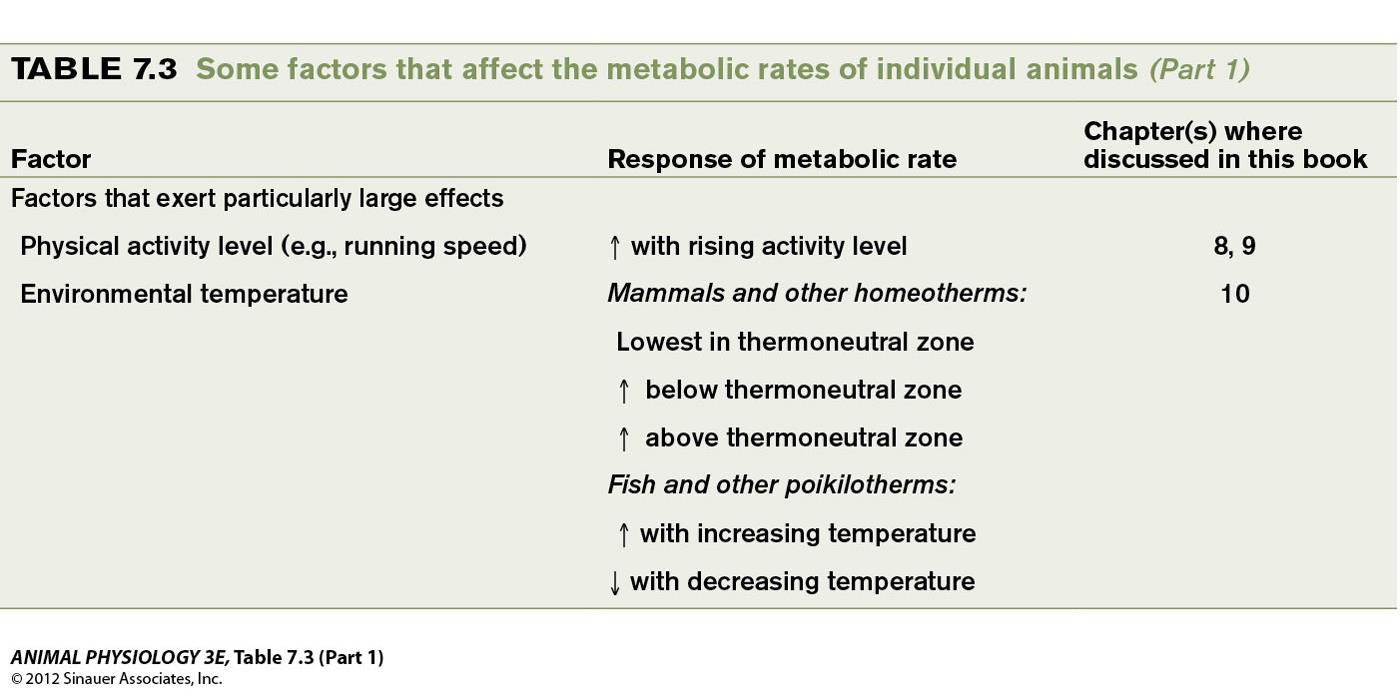

三、Factors affecting metabolic rates

The greatest effectors:

- The intensity of physical activity

- Temperature of its environment

**The smaller effectors: **

- Ingestion of food, age, gender, time of day, body size, reproductive condition, hormonal state, psychological stress, the salinity of the ambient water

Ingestion of food causes metabolic rate to rise

SDA of the ingested food

- Specific dynamic action (SDA) - increase in metabolic rate caused by food ingestion.

- Also called calorigenic effect of ingested food, or heat increment of feeding.

- The magnitude of SDA is roughly proportional to the amount of food eaten

- The SDA is a relatively short-term phenomenon, but some diet induces a Semi-permanent, or chronic change in its metabolic rate – this why some individuals do not get fatten because their metabolic rate is chronically high.

Specific dynamic action (SDA):

- If a resting animal that has not eaten for a while consumes a meal but then remains at rest. its metabolic rate rises afterward-the SDA

- The rate of O2 consumption followed the red line after a 1.4 KJ meal was eaten, but it followed the green line after a fourfold larger meal(5.6 KJ). This result demonstrated that the magnitude of the SDA is roughly proportional to the amount of food eaten

Diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) – long term increase in metabolic rate by persistent overeating – the concept is very important in anti-obesity process.

- The relation between SDA and DIT is not clear at the present!

Basal metabolic rate and standard metabolic rate

Basal metabolic rate (BMR)

- applies to birds and mammals - homeotherms –恒温动物

- Animals that physiologically regulate their body temperature (恒温动物).

- In its thermoneurtral zone

- Fasting

- resting

Standard metabolic rate (SMR)

- applies to fish, amphibians, molluscs poikilotherms (ectotherms) – Animals do not regulate their body temperature (冷血动物;变温动物).

- Fasting

- Resting

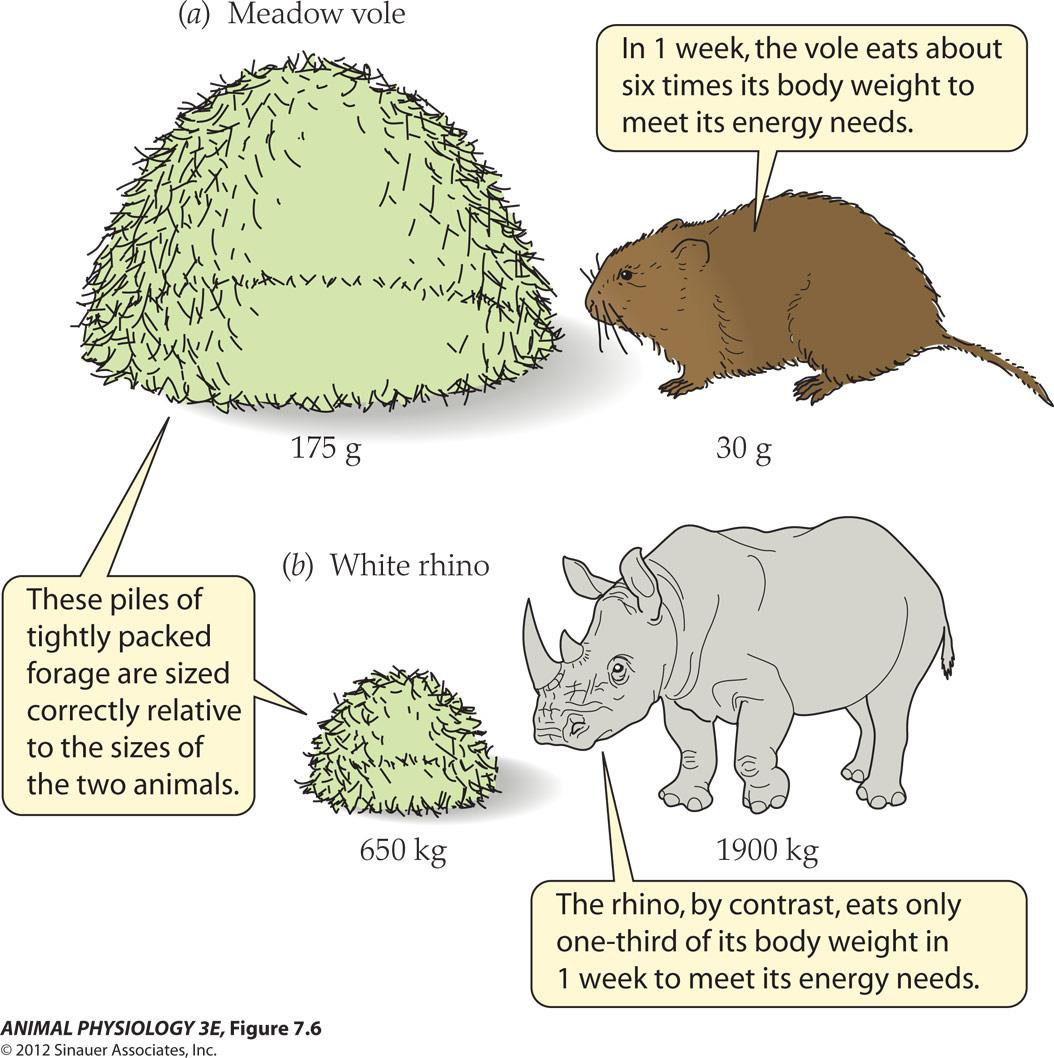

Metabolic scaling

Metabolic scaling: the relation between metabolic rate and body size

Metabolic scaling or metabolism-size relation:

- The study of the relation between metabolic rate and the body size is known as the study of metabolic scaling or the metabolism-size relation.

The effect of body size on weekly food requirements

- The energy needs Of the species are Not proportional To their respective Body sizes

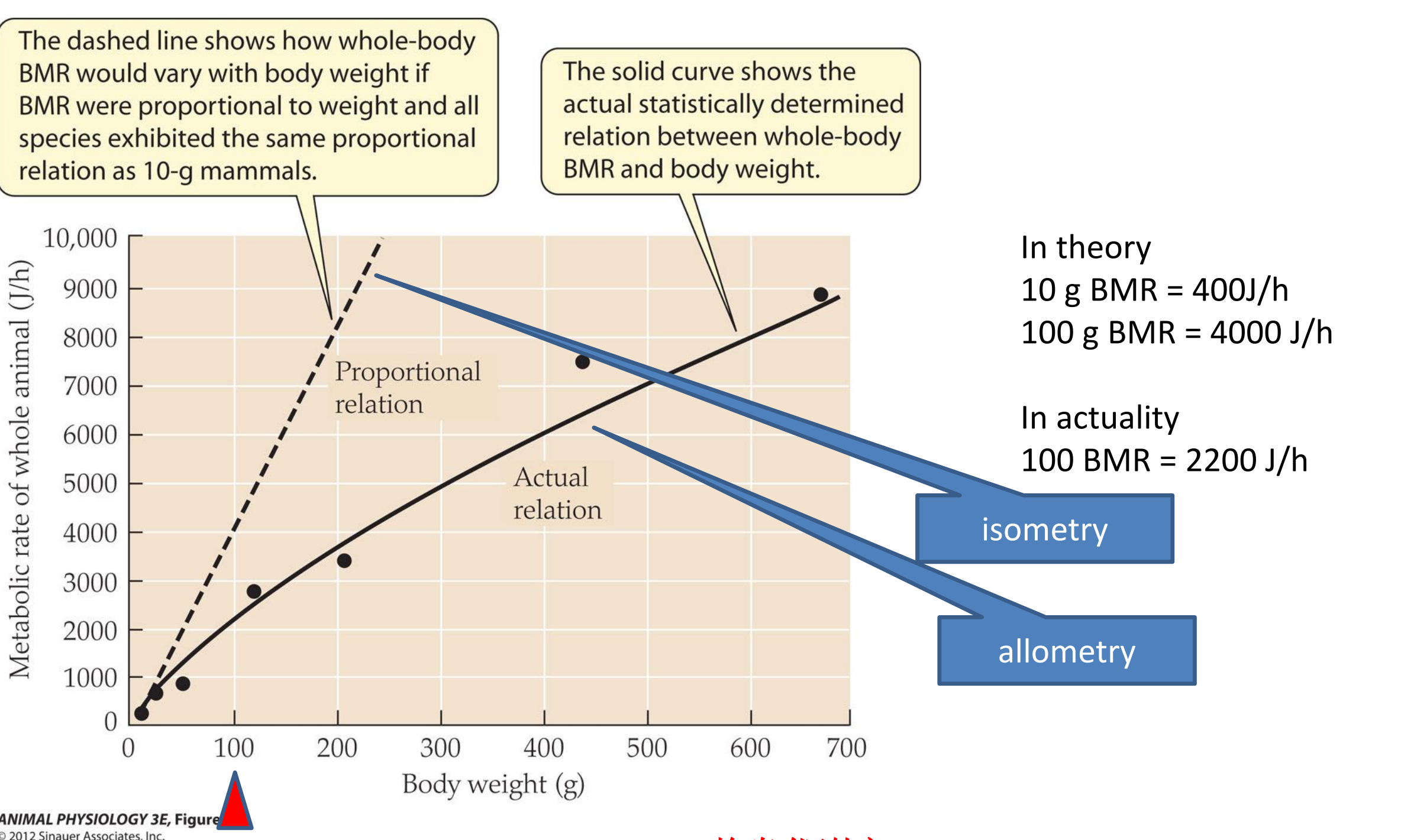

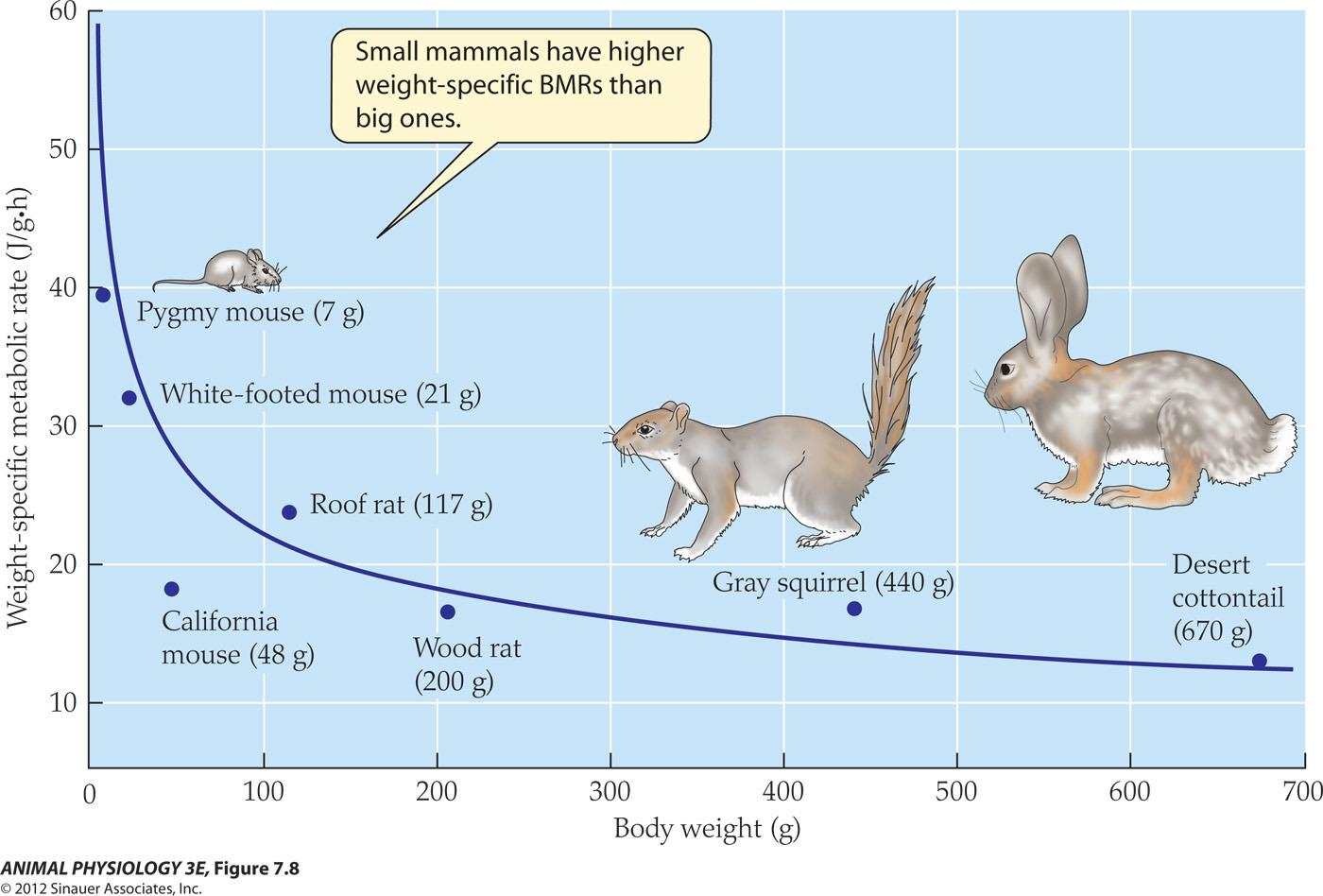

1. BMR as a function of body weight in various species of placental mammals

- In theory

- 10 g BMR = 400J/h

- 100 g BMR = 4000 J/h

- In actuality

- 100 BMR = 2200 J/h

Resting metabolic rate (静息代谢率) is an allomertric function of body weight in related species (allometry function 异速功能)(allo = different, metric = measure)

2. Equation

$$

M = aW^{b}

$$

- (The power function 幂函数关系)

- M is whole animal metabolic rate

- W body weight

- a and b are constants (b is scaling exponent )

- If b=1, then M=aW, a proportional relationship.

- However, b is almost never = 1, so this equation is nonproportional And is known as an allometric equation

The metabolic rate of animals are said to be “allometric functions of Body size”.

- (allo = different, metric = measure)

Isometry:

- Geometrically similar objects exhibit what is called isometric scaling (iso = same, metric = measure); the relationships between surface area, volume, and length follow the simple rules we noted earlier. That is, if we consider a species of snail that exhibits a constant shape regardless of size, then the volume enclosed by its shell will be proportional to its (height) . To test this, you could collect 100 shells of different sizes, measure the height and volume of each, and plot log(volume) vs. log(height). If scaling is isometric in the shells of this species, then the data should fall along a straight line with slope b = 3.

Allometry:

- When an animal (or organ or tissue) changes shape in response to size changes (i.e., does not maintain geometric similarity), we say that it scales allometrically (allo = different, metric = measure). Allometric scaling is common in nature, both when comparing two animals of different sizes and when comparing the same animal at two different sizes (i.e., growth). The reasons, and there are many, underlying this rule will keep us occupied for much of this course.

3. weight-specific metabolic rate

An alternative to examine the relationship between metabolic rate vs body weight is to calculate the metabolic rate per unit of body weight

- weight-specific metabolic rate (Weight specific BMR)

- 70 kg – human produces 10% as much heat per gram as the mouse 4000 kg elephant produces 5% as much

$$

M = aW^{b}

$$

Now biologists have discovered that the exponent of b in the allometric relation between total resting metabolic rate, M and W exhibits an impressive consistency in its value from phylogenetic group to another.

The value of b for the resting metabolic rates of diverse groups of animals tends to be about 0.7.

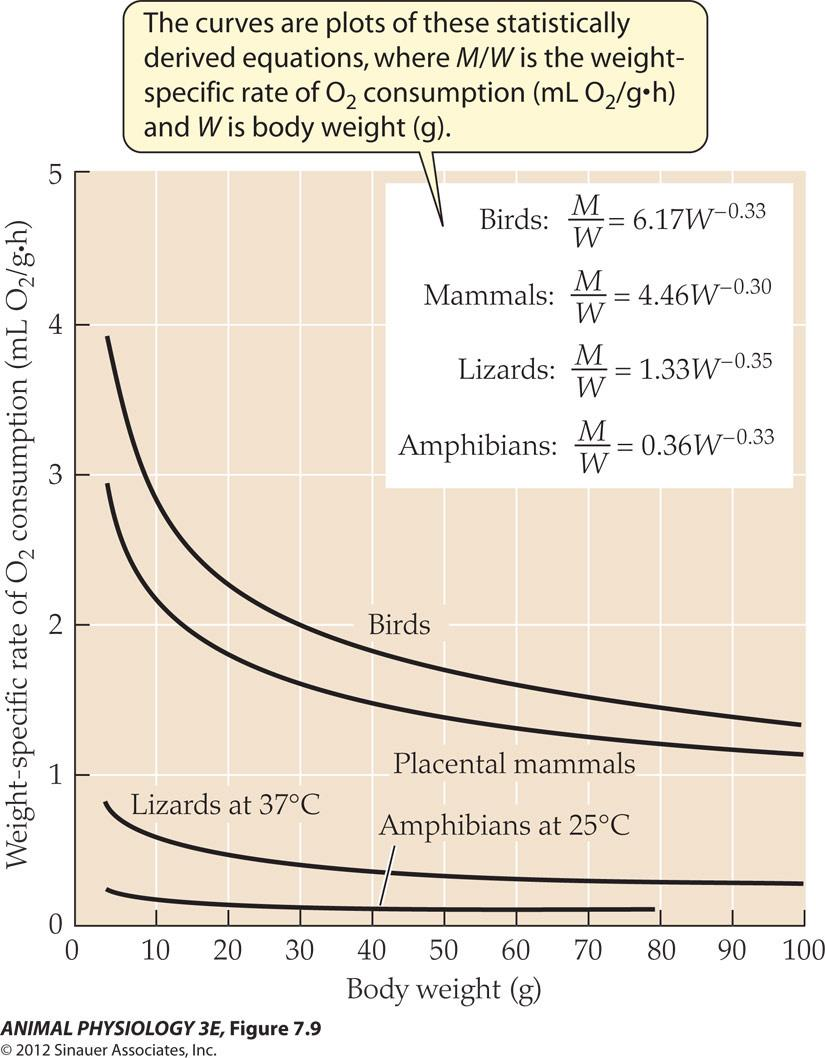

The mathematical relationship between weight-specific resting metabolic rate and the body weight is now as:

$$

M/W = aW^{(b-1)}

$$

- ($b$ is about 0.7, so the exponent here is

-0.3; the sign–indicates weight specific resting metabolic rate decreases with increasing body weight - (a high $a$ value means high metabolic intensity)

- Note similarity of the exponents but differences in a, signifying Different metabolic intensities In four types of animals.

- Allometric relationship between Metabolic rate and body weight!

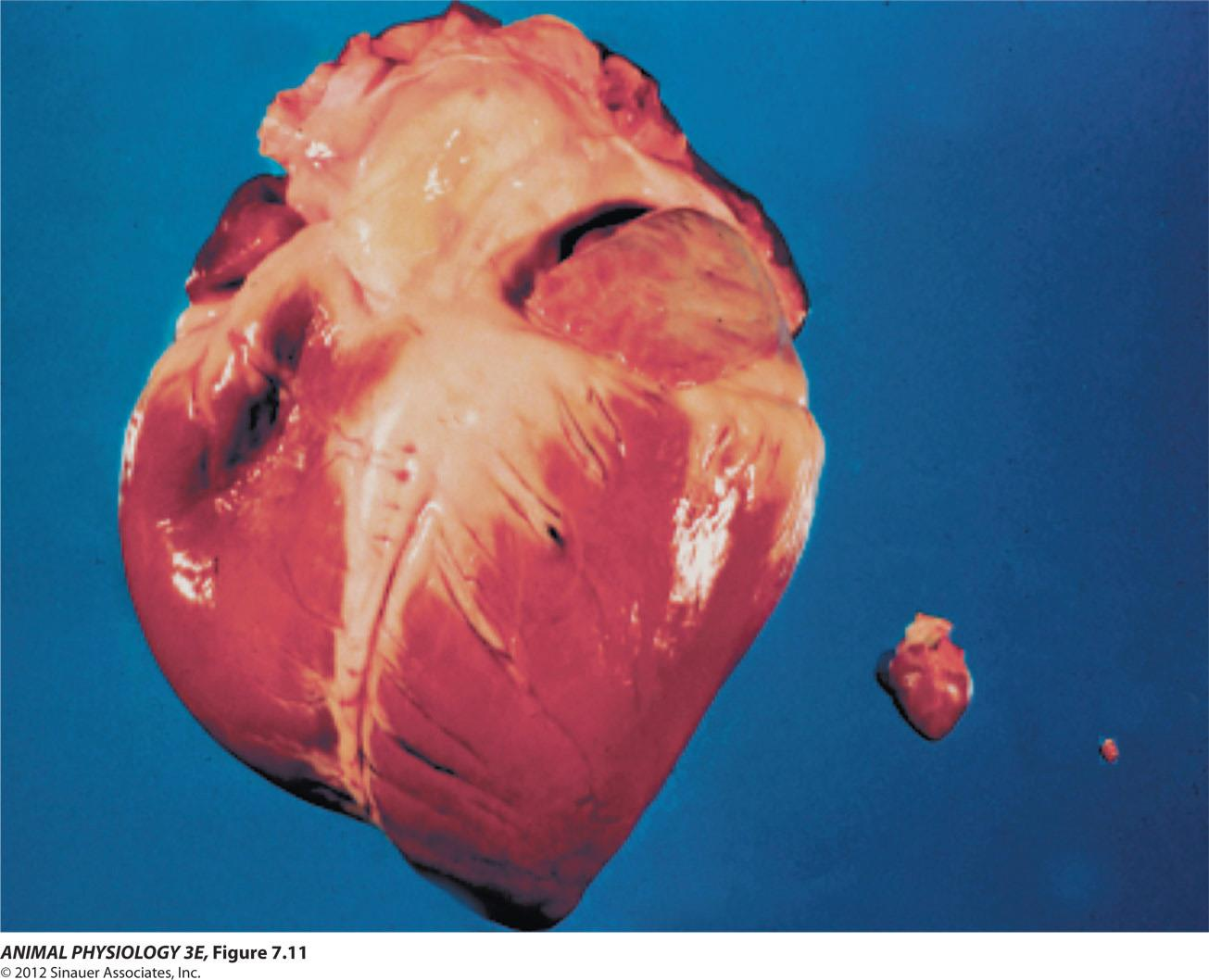

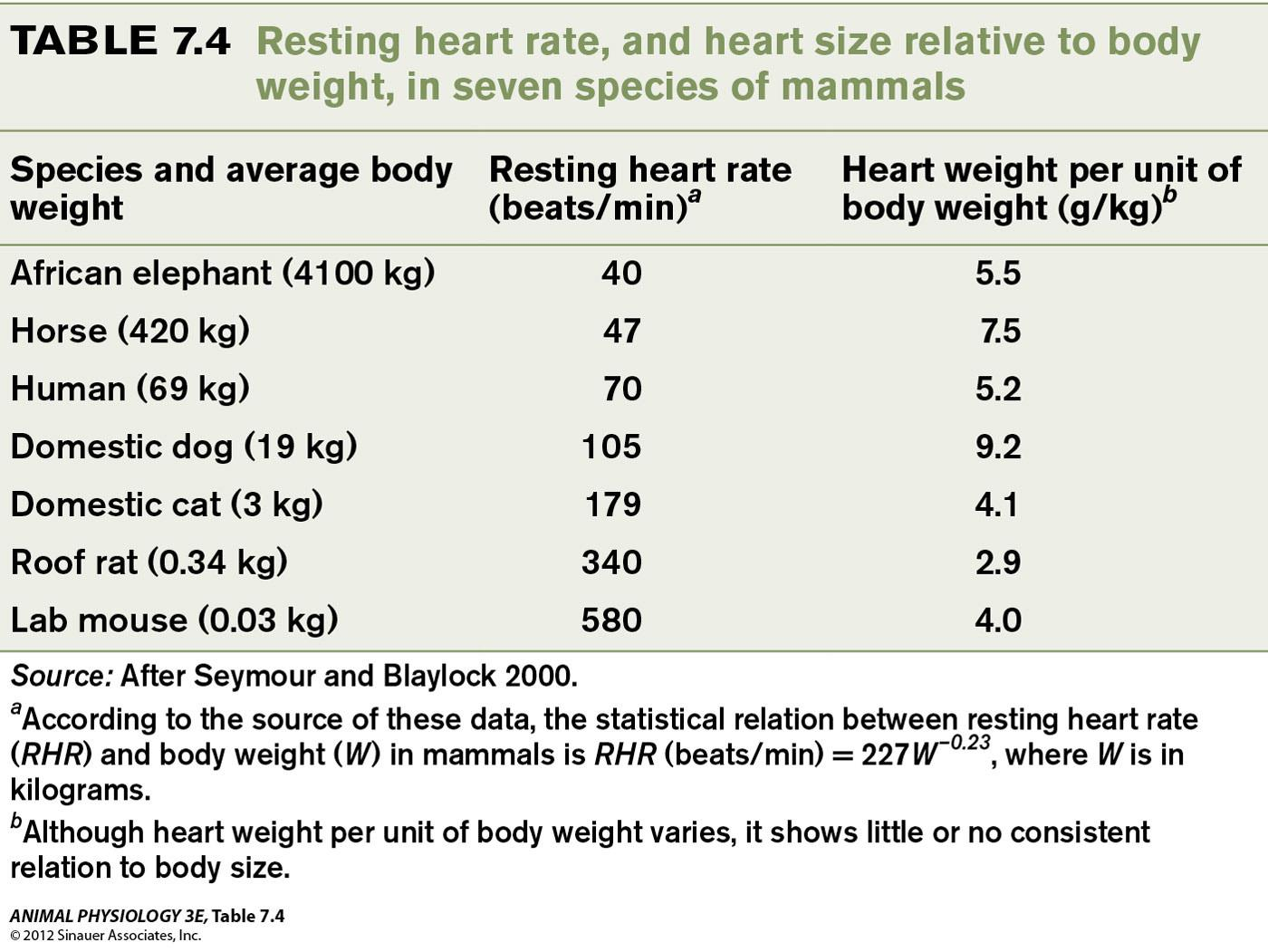

Hearts of a horse, cat, and mouse: Heart size in mammals is roughly proportional to body size:

- The metabolism-size relation has important physiological and ecological implications

The metabolism-size relation has important physiological and ecological implications

- Why smaller animals have far higher heart rates than do the larger ones?

- This is because, statistically all animals have the same size heart in relation to their body size.

- Small animals require more O2 per gram of body weight than the large ones; therefore the smaller animals must beat faster than The larger animals to deliver the O2.

- Human breathe 12 times/min, while mice breathe 100 times/min

- Ecologically, 3500 mice at 20g each (70,000 g) place the same demand on a woodland ecosystem as single 70,000 g deer? NO!!!

- The weight-specific BMR of mouse is 8 times of that of a deer, so 440 mice is equivalent to that of a deer.

The explanation of allometric metabolism-size relations remain unknown

- The allometric exponent b = 0.7 in diverse groups of animals is intriguing!

- For a century, the greatest minds in biology is grappled with the question

- Why metabolic rate and body size are related allometrically?

- Why the allometric exponent is sometimes so impressively consistent?

- Yet there is no consensus about how to explain the allomerices!

Rubner’s surface “law”

S(sphere area) ∝ r^2^ (radius) v (volume) ∝ r^3^ , s ∝ v^2/3^ **(**∝ 正比例,proportional)

Big spheres have less surface area per unit of volume;

- This law states that BMR of a mammal is proportional to its body-surface area.

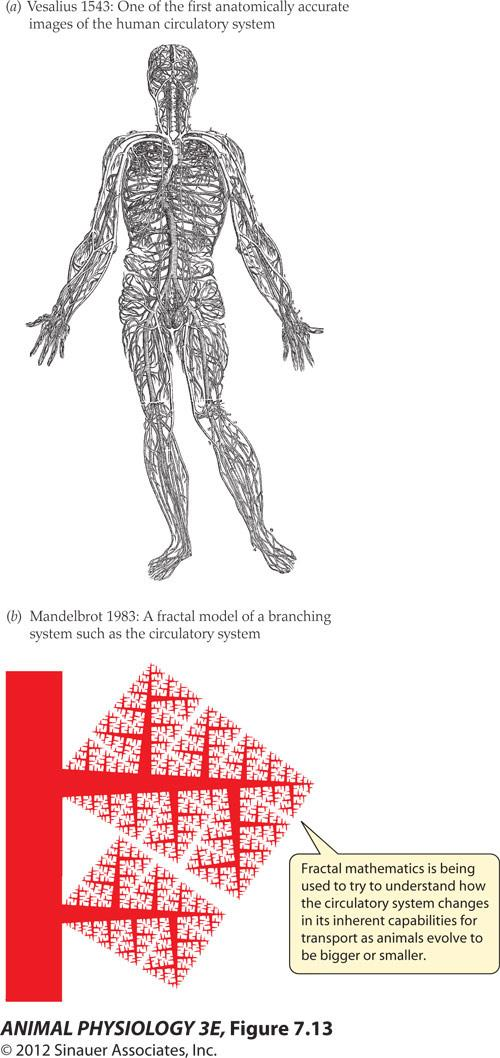

As the circulatory system is scaled up and down in size and extent, constraints predicated on fractal geometry may help give rise to allometric metabolic scaling

Recent research shows that exponent b generally tends to be similar in many animal groups, but it is not identical!

- In fact the exponent b is not a constant.

So physiologists have turned to the circulation system, a key for metabolism, as model system to understand the Allomertric relationship between metabolism and body size.

Summary

Metabolic Scaling: The Relation between Metabolic Rate and Body Size

- BMR, SMR, and other measures of resting metabolic rate are allometric functions of body weight within phylogenetically related groups of animals ($M=aw^{b}$, where b is usually in the vicinity of 0.7). Small-bodied species tend to have higher weight-specific metabolic rates than do related large-bodied species, an effect so great that the weight-specific BMR is 20 times higher In mice than in elephants

- Maximal aerobic metabolic rate also tends to be an allometric function of body weight in sets of related species. In many cases studied thus far, the allometric exponent for maximal metabolic rate differs from that for resting metabolic rate

- The allometric relation between metabolic rate and weight exerts important effects on the organization and structure of both individual animals and ecosystems. Heart rates, breathing rates, mitochondrial densities. and dozens of other features of individual animals are allometric functions of body weight within sets of phylogenetically related species. In ecosystems, population biomasses and other features of community organization may vary allometrically with individual body size

- Physiologists are not agreed on the explanation for the allometric relations between metabolic rate and body weight Rubner’s surface” law based on heat loss from homeothermic animals, does not provide a satisfactory explanation. Many of the newest hypotheses recognize that the allometric exponent varies in systematic ways and seek to explain that variation, as by examining evolutionary constraints in resource distribution systems such as the circulatory system

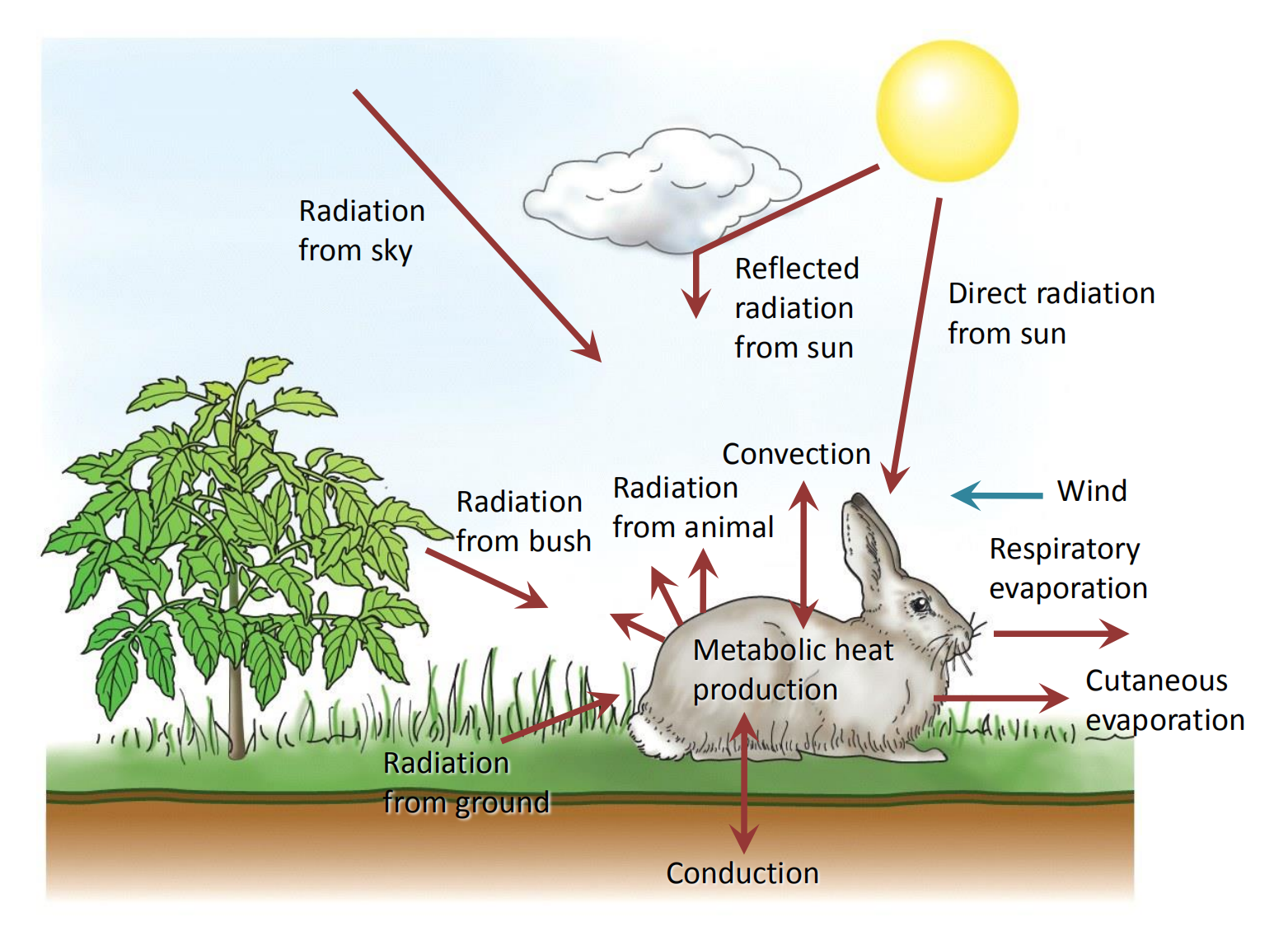

An animal exchanges heat with its environment by conduction, convection (对流), evaporation, and thermal radiation

四、Food, Energy and temperature at work

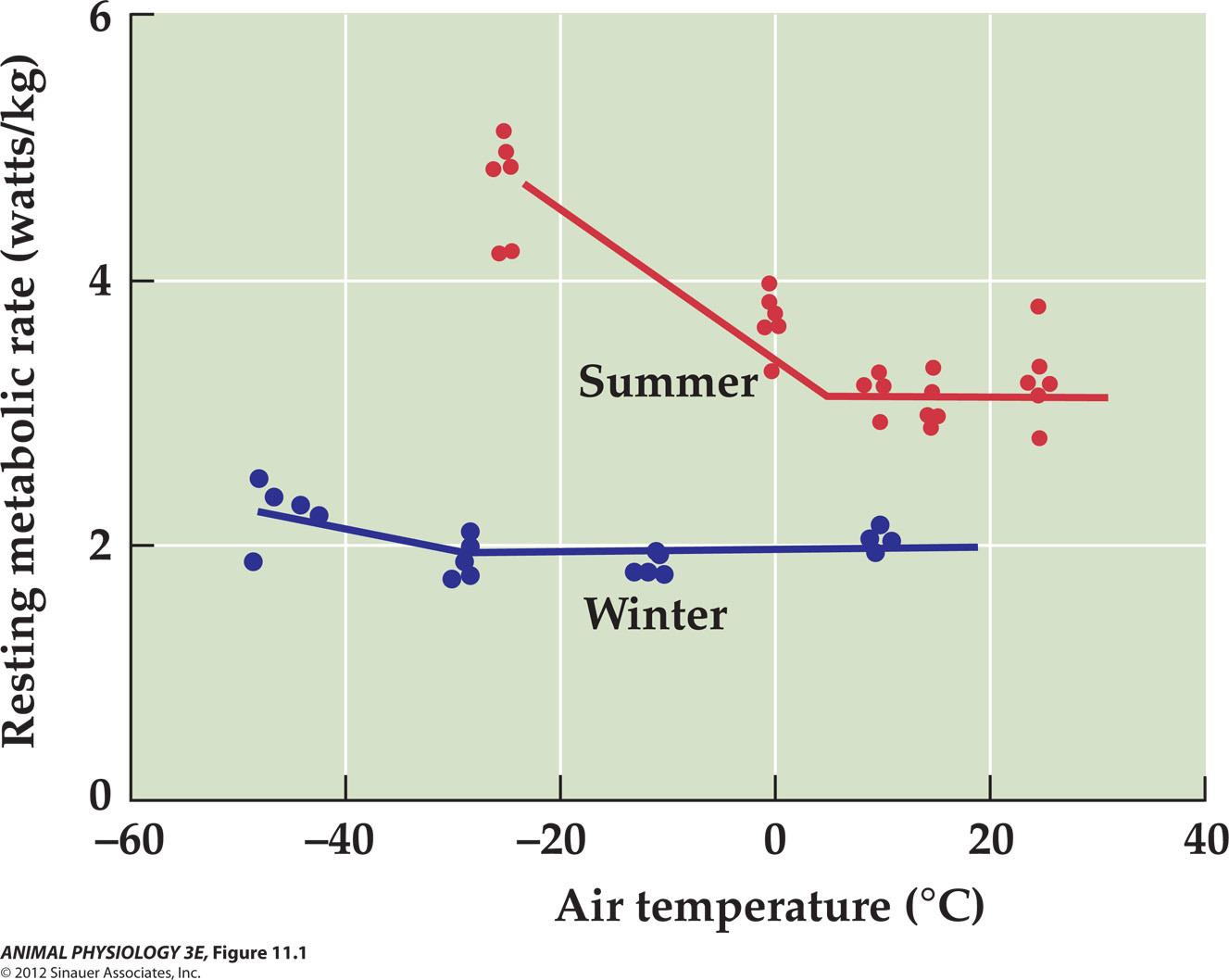

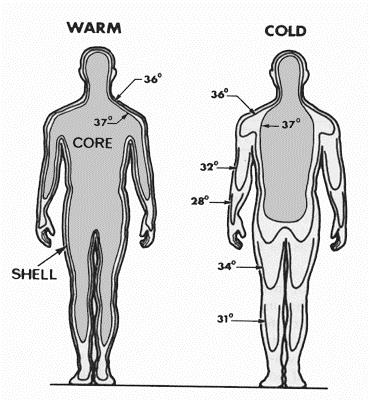

Resting metabolic rate as a function of air temperature down to –50°C in adult reindeer

Adult reindeer in winter pelage (毛发)in still air never have to increase their metabolic rate by much above basal!

Fur thickness of adult reindeer in winter and summer

- One reason for the low energy costs of adult reindeer is

- the pelage

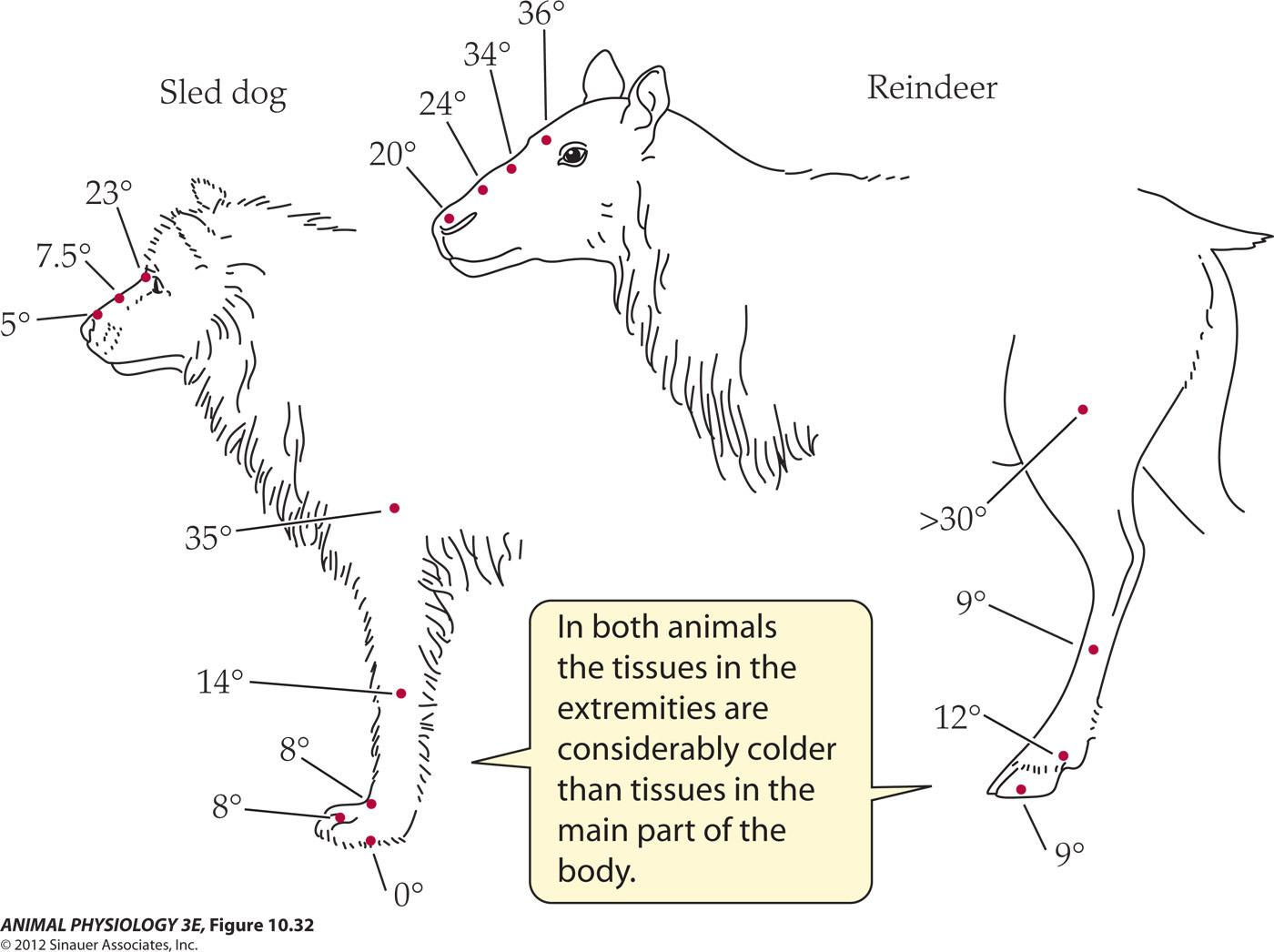

- They employ regional heterothermy (legs and exposed body part are not as warm as the body core)

- The fatty acid of the legs are very fluidic.

**Regional heterothermy in Alaskan mammals: **

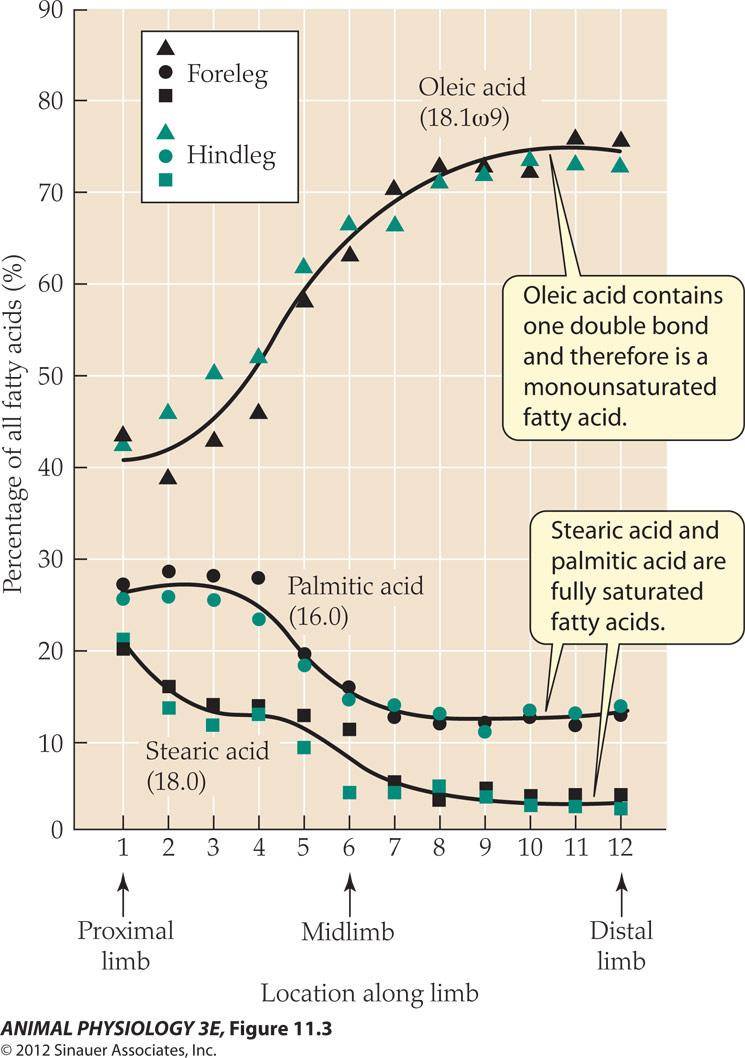

**Fatty acid composition of bone marrow lipids in the legs of reindeer: **

- Oleic acid contains one double bond and therefore is a monounsaturated fatty acid

- Unsaturated fatty acids become more abundant

- Stearic acid and palmitic acid are fully saturated fatty acids

- Saturated fatty acids become Less abundant.

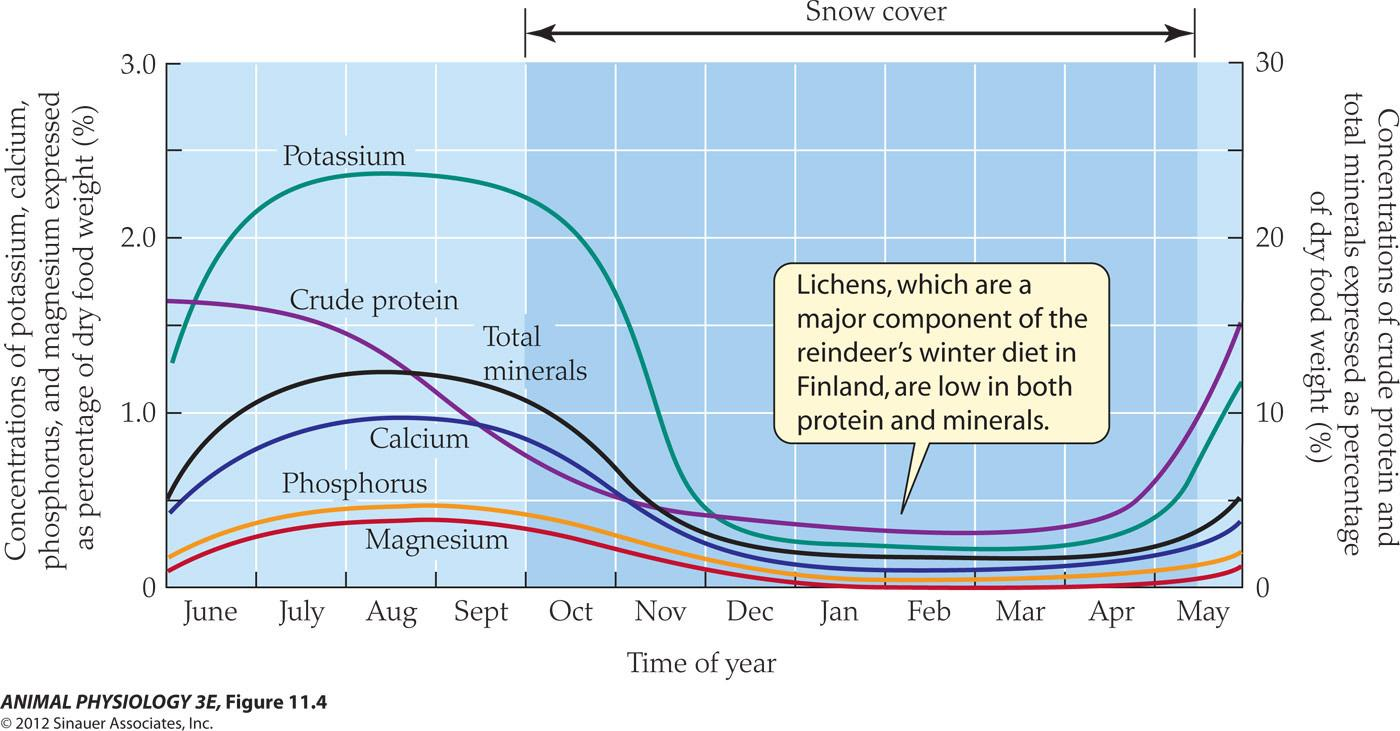

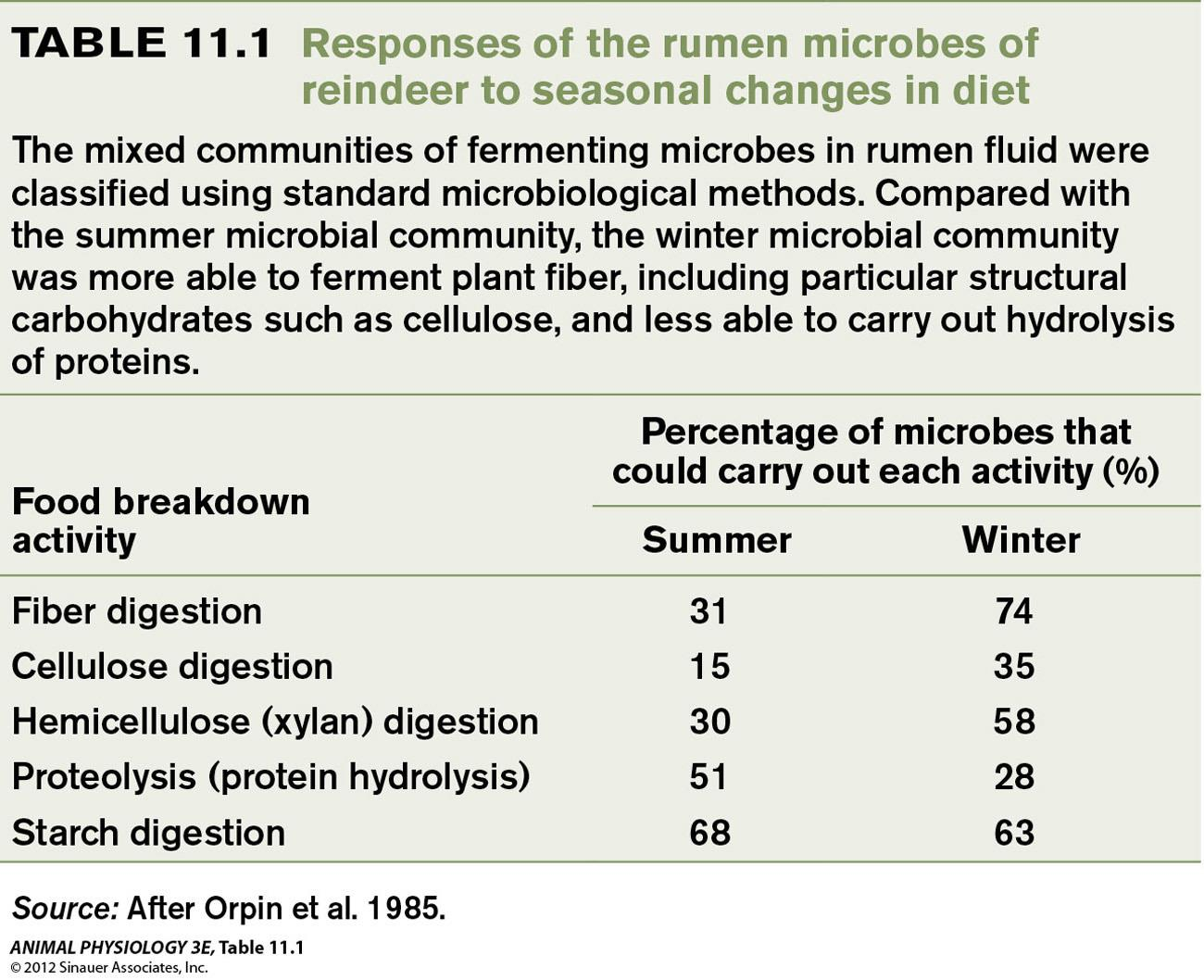

Seasonal changes in diet: the protein and mineral content of the foods eaten by Finnish reindeer

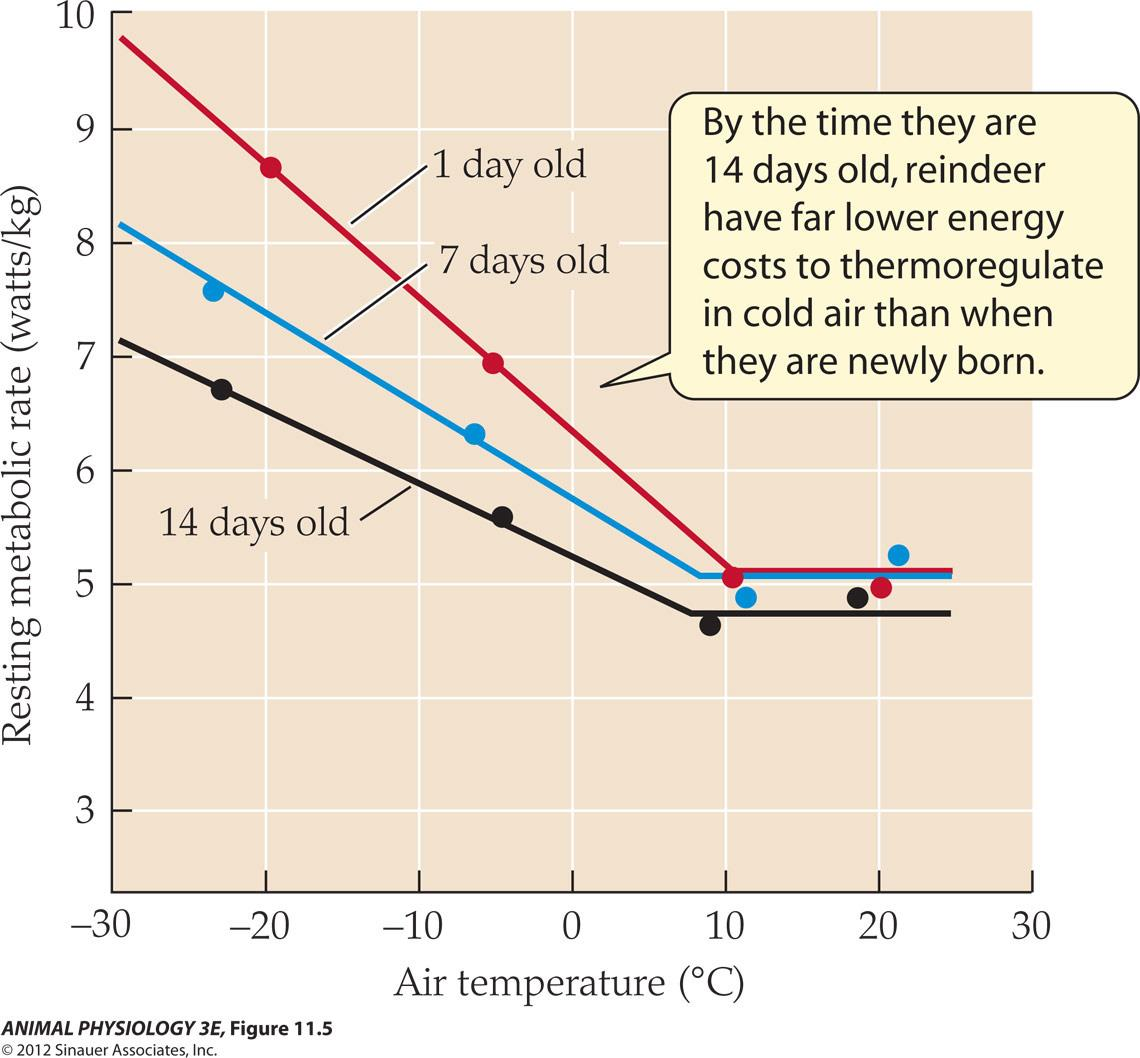

Resting metabolic rate as a function of air temperature in newborn and growing reindeer

- New born body temperature Is at 39-40, when the air is -20 °C

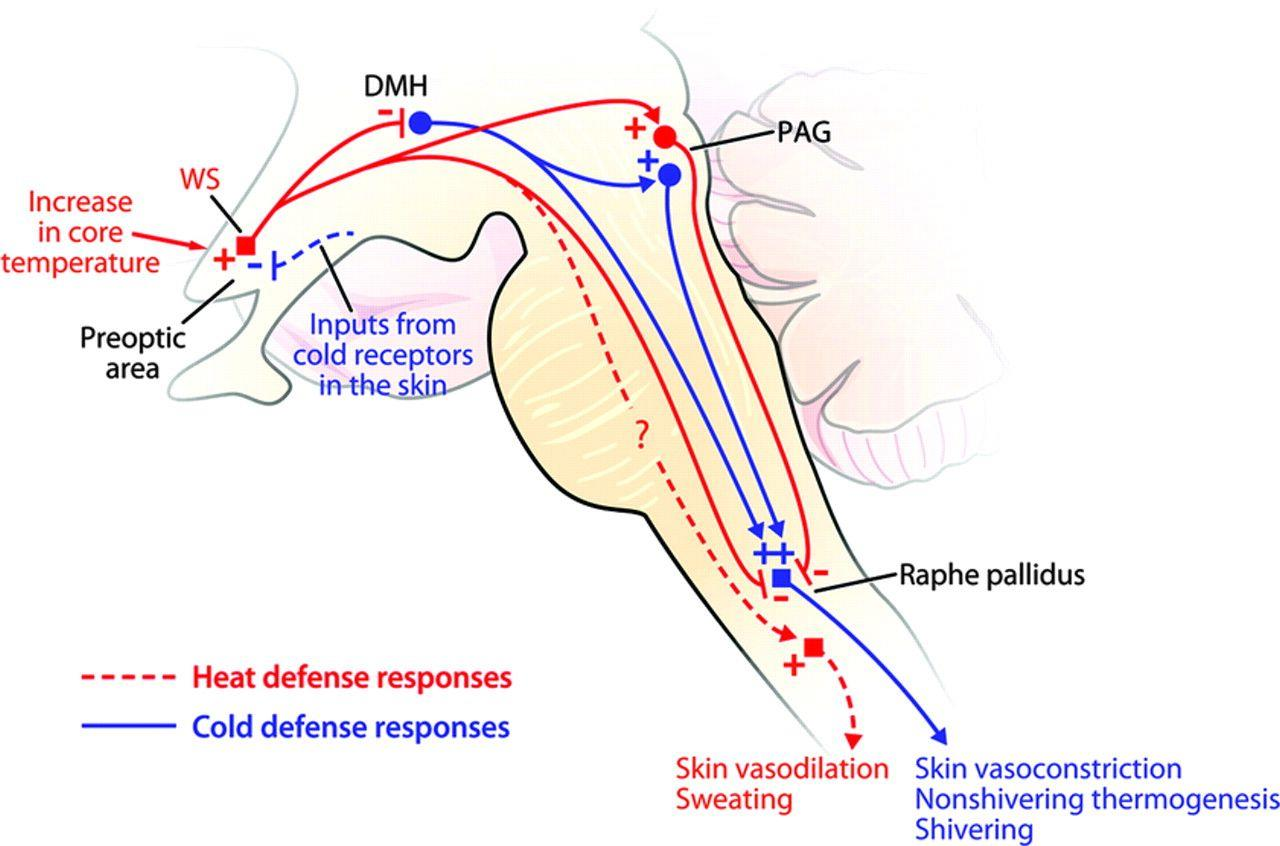

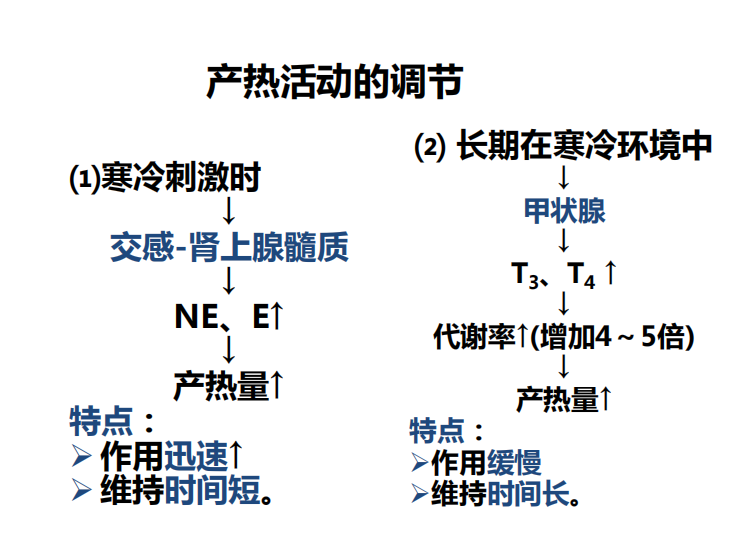

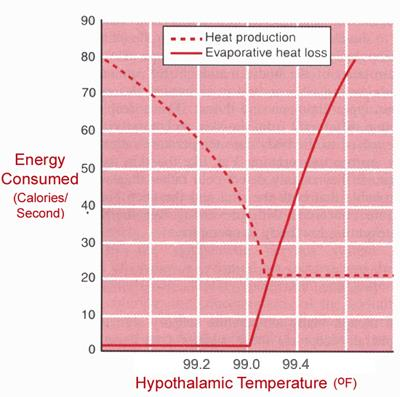

Heat production by thermoregulation (Ch 10, p256)

When the animal is below its lower-critical temperature, it must increase its rate of heat production mammals and birds use thermogenic mechanisms to generate heat for thermoregulation

shivering (unsynchronized contraction and relaxation of skeletal muscle motor units in high frequency rhythms. This contraction uses ATP and generates heat!)

Nonshivering thermogenesis (brown fat, brown adipose tissue – BAT).

- Shivering is universal, while NST is not!

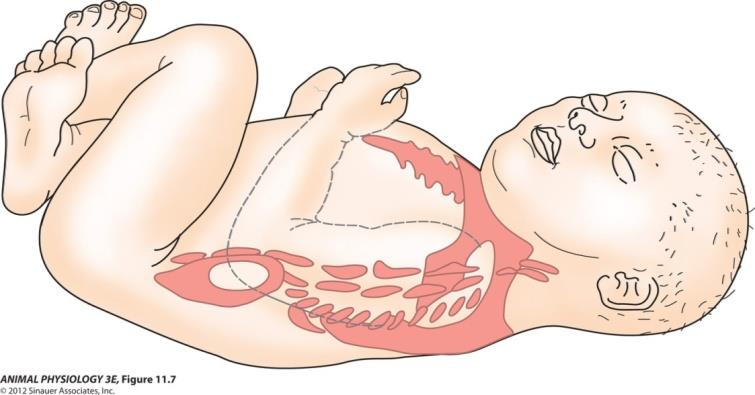

1. Brown adipose tissue in a human infant

Deposit of brown fat receives rich supply of blood vessels and are innervated By the sympathetic nervous system.

BAT has large numbers of mitochondria and yellow cytochrome pigments in its mitochondria.

Brown fat tends to be in discrete masses located in the neck, abdomen(腹部), etc.

Brown fat – like NST in general – is particularly prominent in 3 types of mammal

- Cold-acclimated or winter acclimated adults

- hibernators 冬眠动物

- newborns 新生儿

Sympathetic nervous system releases norepinephrine in BAT and the BAT responds by greatly increasing its rate of oxidation of its stored lipids, resulting in a high rate of heat production

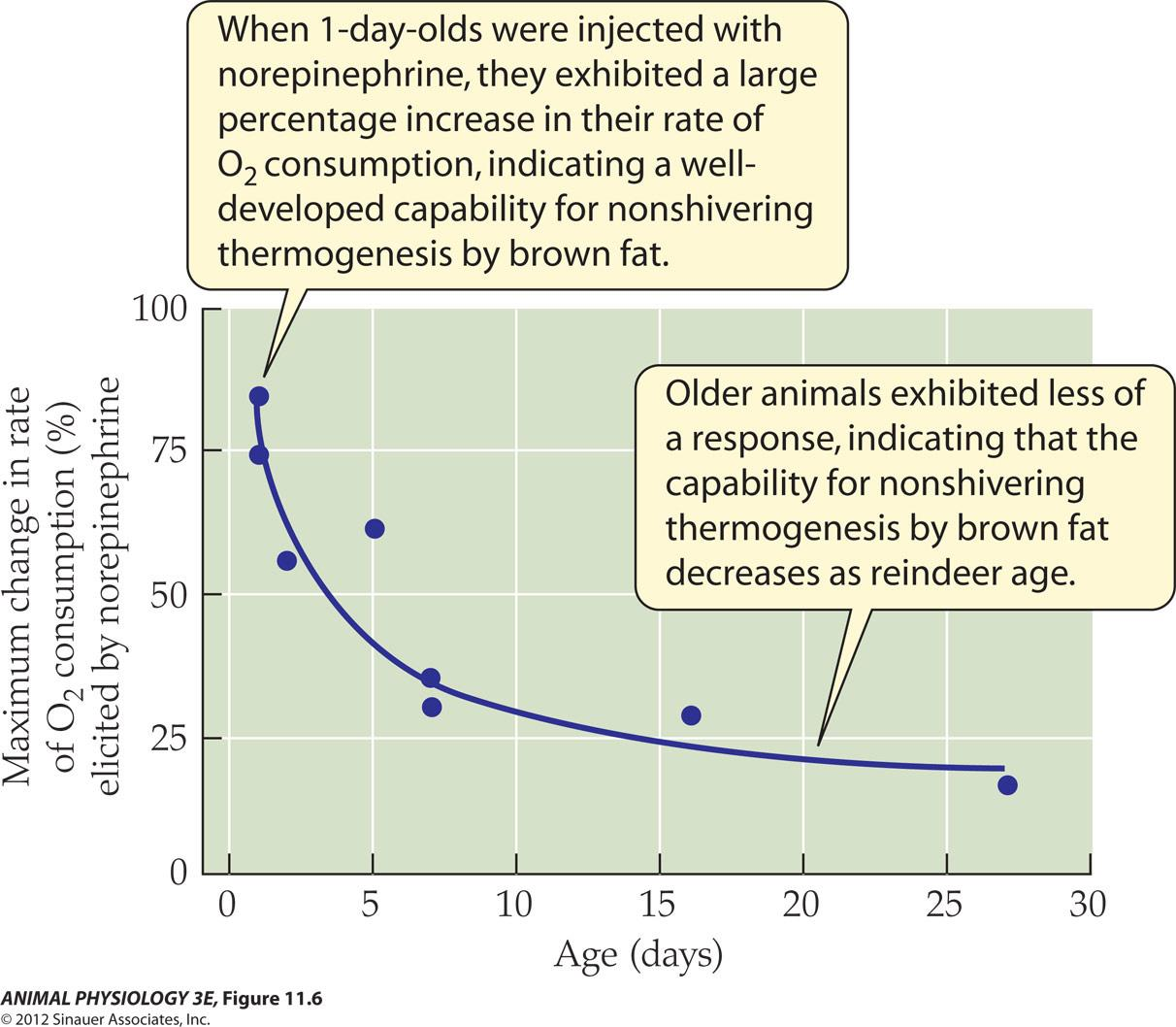

A test for brown-fat thermogenesis in newborn and growing reindeer:

- norepinephrine 去甲肾上腺素

Knockout Mice Clarify the Function of Brown Fat:

- Molecular genetic tools have been used to produce lab mice that can not synthesize the type of mitochondrial protein – uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), that mediates nonshivering thermogenesis (NST).

Results:

- brown fat is the sole tissue in which NST occurs.

- UCP1 is the only molecular form of UCP that mediates NST

Regional heterothermy: in cold environments, allowing some tissue to cool can have advantages

- Appendages (legs, tails, eye pinnae, etc) have low circulatory delivery and consist of mainly bones, cartilage, skin, which have low metabolic rate

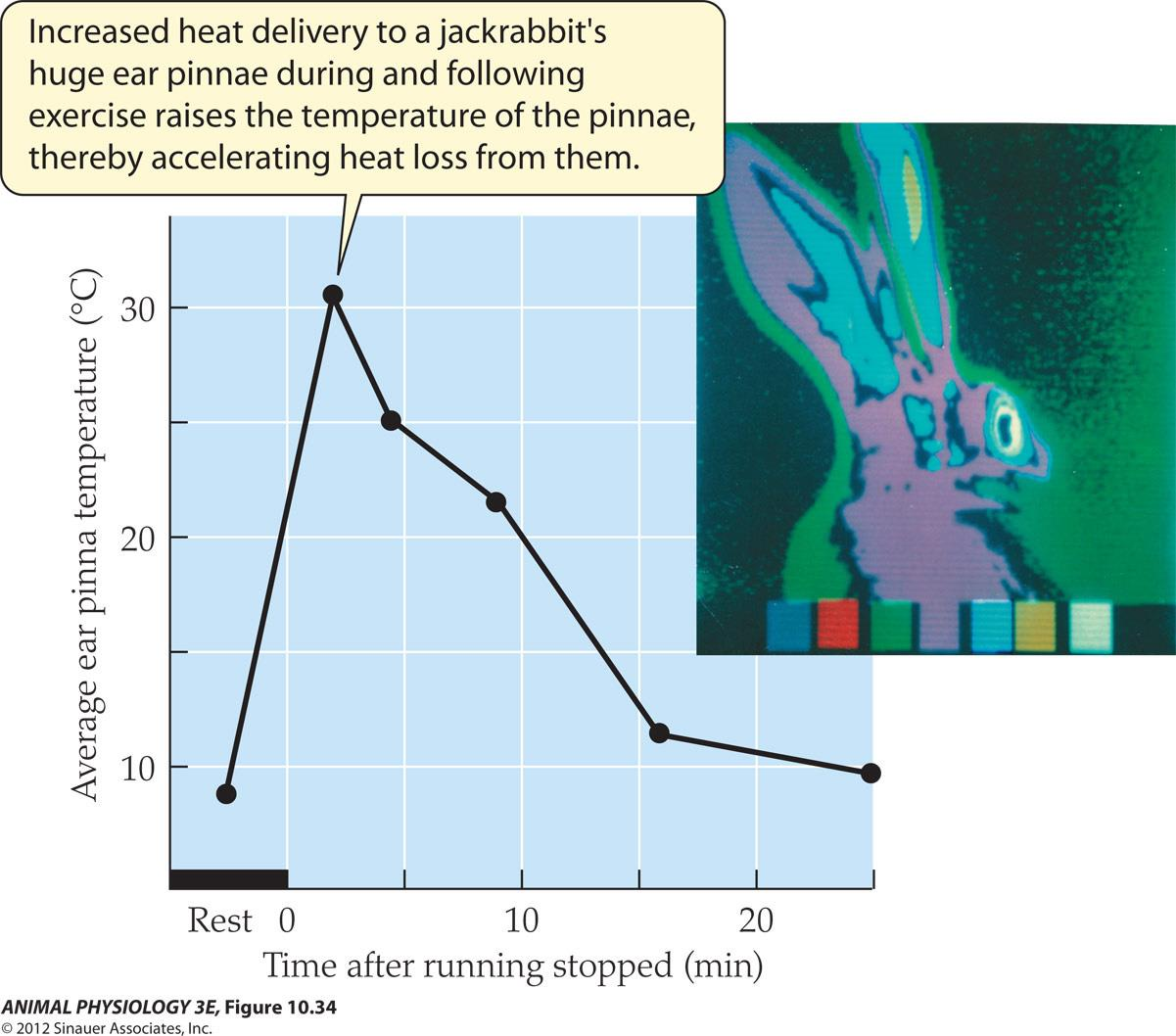

Heat loss across appendages (耳廓) is sometimes modulated in ways that aid thermoregulation

- Increased heat delivery to a jackrabbit’s huge ear pinnae during and following exercise raises the temperature of the pinnae, thereby accelerating heat loss from them

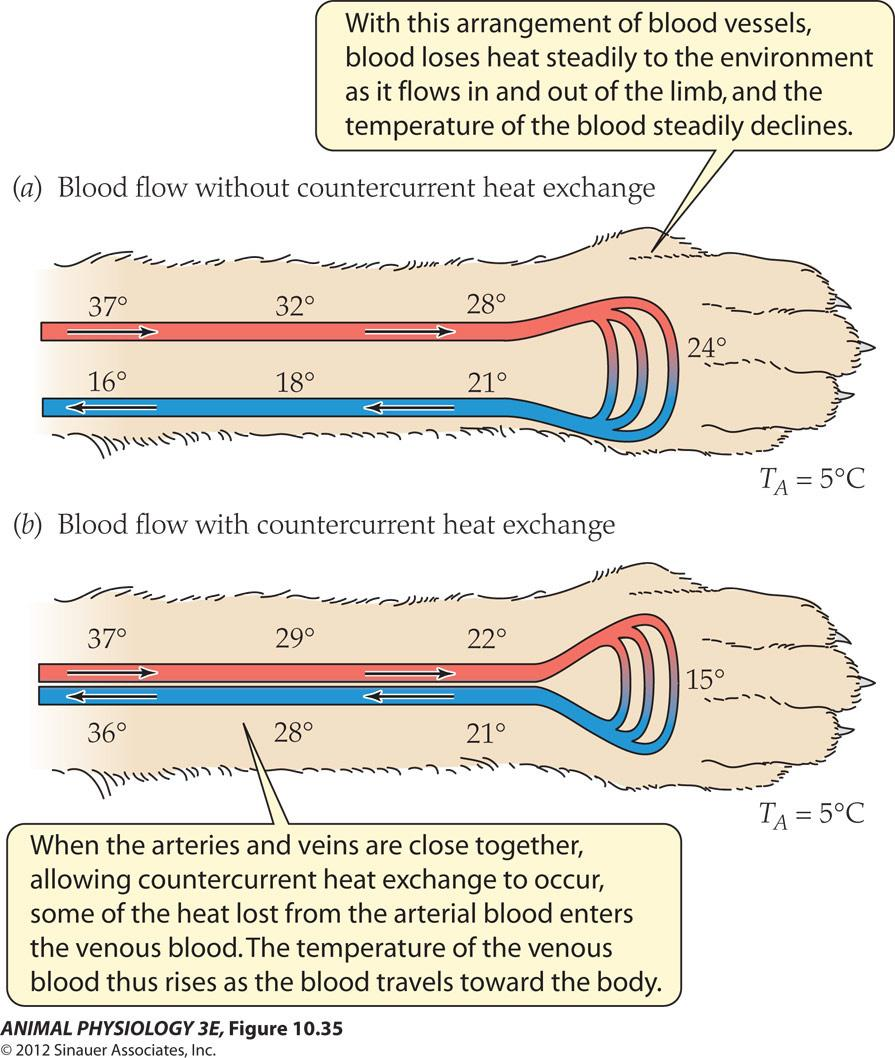

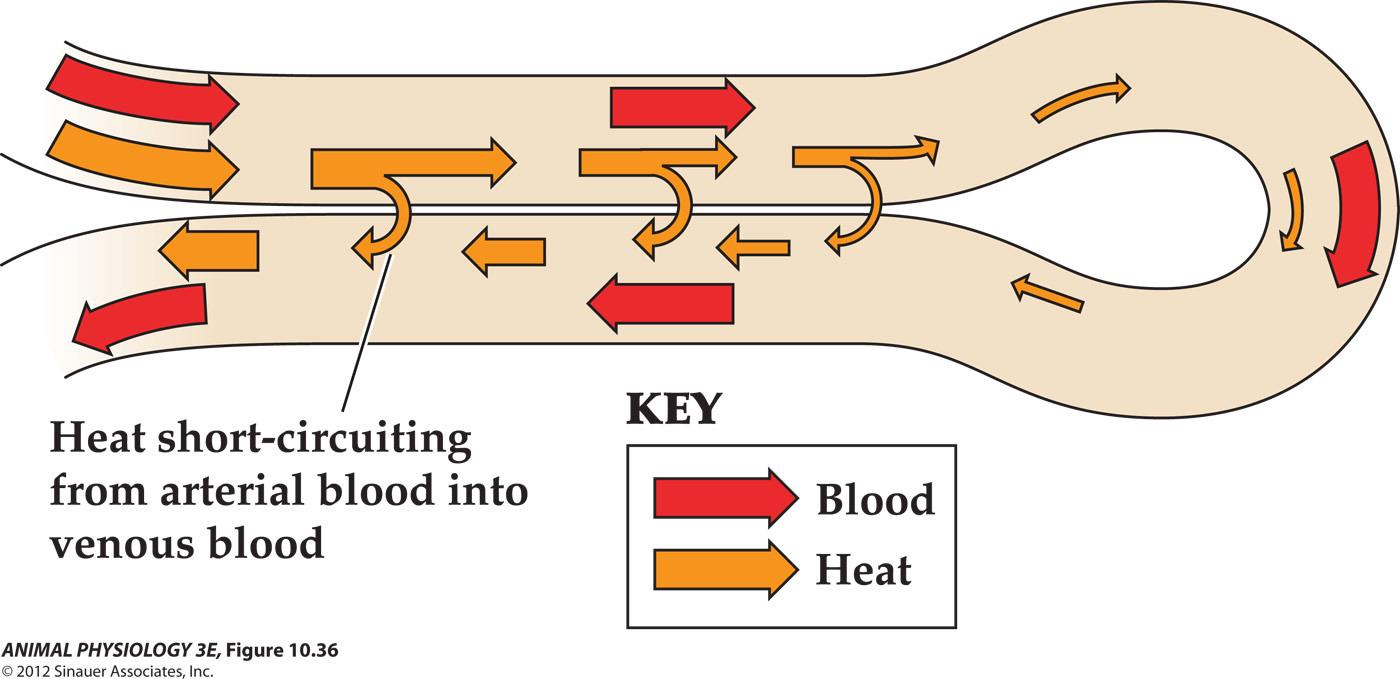

Countercurrent heat exchange permits selective restriction of heat flow to appendages

- Countercurrent heat exchange: heat exchange depends on the transfer of heat between two closely juxtaposed fluid streams flowing in opposite directions

Blood flow with and without countercurrent heat exchange

- With this arrangement of blood vessels blood loses heat steadily to the environment as it flows in and out of the limb, and the temperature of the blood steadily declines

- When the arteries and veins are close together allowing countercurrent heat exchange to occur, some of the heat lost from the arterial blood enters the venous blood. The temperature of the venous blood thus rises as the blood travels toward the body

Countercurrent heat exchange short-circuits the flow of heat in an appendage

- short-circuits

Mammals and bird in hot environments: Their first line of defense are not evaporative cooling

Evaporative cooling may help for temperature regulation, but it may create problems of water regulation, a potential lethal price to pay

So the first line of defense is nonevaporative defense

- Behavioral defenses (living underground borrows,)

- Insulatory defenses (thick pelages and plumages acting as heat shields)

- Body temperature (cycling of body temperature)

- Camels example: 34-35 °C in the night and 40C in the day, 3.3J is required to warm 1 g of camel flesh by 1 °C, 400kg needs 7920kJ to raise 6 °C. To remove this amount of heat needs 3 liter of water)

- Hyperthermia

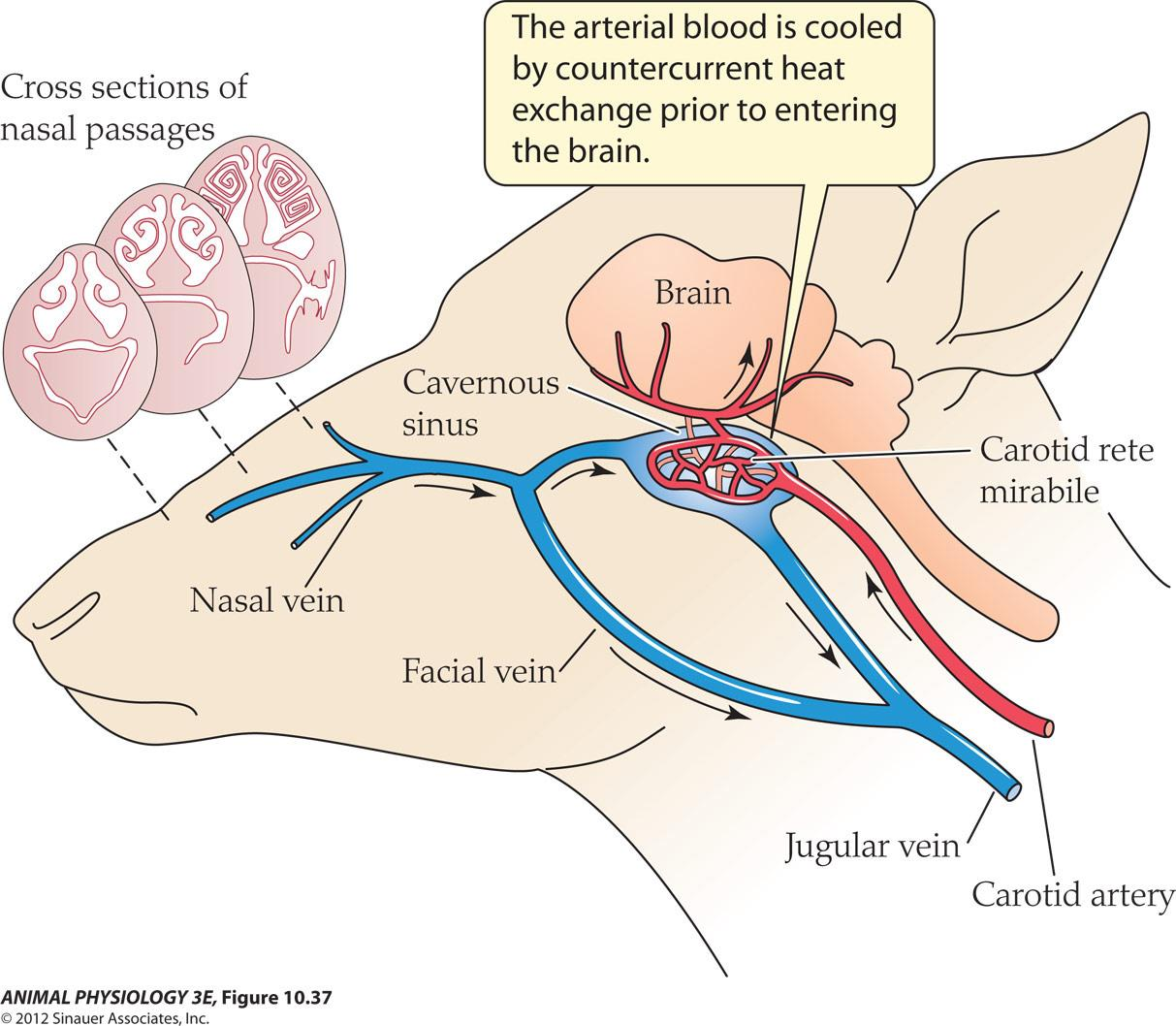

- Keeping a cool brain

Structures hypothesized to be responsible for cooling the brain in sheep and other artiodactyla(偶蹄目)

Active evaporative cooling is the ultimate line of defense against overheating

- Sweating – contains Na+ and Cl(lower than the blood plasma), prolonged sweating will deplete body pool of Na+ and Cl-

- Panting(气喘吁吁)– increasing the rate of breathing in response to heat, no lost of salts, because evaporation occurs within the body.

- Gular fluttering – birds only, vibrating their gular area while holding their mouth open

Questions

- What are the relative advantages and disadvantages of large and small body size in frigid places?

- Malnutrition of children is a profound global problem, and protein deficiencies are the most common form of childhood malnutrition. Why are people so vulnerable to protein deficiencies?

- Explain how and why the absorption of hydrophobic and hydrophilic organic molecules differs.

- List three major roles played by each class of foodstuffs: proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids.

- Explain mechanistically how hyperventilation alters the oxygen cascade of an animal/human.

- Both respiration and heart beat are rhythmic. Describe the differences between the two.

体温及其调节综述

体温: 机体深部的平均温度。

体温恒定的维持有赖于机体产热和散热过程的平衡。

- 体表温度: 包括皮肤、皮下组织和肌肉等机体表层的温度,又称表层温度。

- 体核温度: 包括心、肺、脑和腹部器官等机体深部的温度,又称深部温度。

- 体核温度比体表温度高,且比较稳定。

1. 动物的体温及其正常变动

体温

正常新陈代谢要求在一定的温度条件下进行。哺乳动物的体温超过42℃或低于25℃,将引起代谢严重障碍甚至死亡

所以,正常的体温对于生命活动具有重要意义,也是机体健康状况的重要指标。

动物体温的生理波动

家禽的体温比家畜高

幼畜的体温比成年家畜略高

母畜较公畜略高

发情期、妊娠期体温较高,排卵时体温降低

肌肉活动时体温升高

采食后体温升高0.2~1℃,持续2~5h之久

清晨2~6时体温最低,午后1~6时最高

机体产热的其它形式

- 战栗产热(shivering thermogenesis):

- 骨骼肌同时发生不随意的节律性收缩。屈肌和伸肌同时收缩,不做外功,但产热量很高。代谢率可增加4-5倍。

- 非战栗产热(non-shivering thermogenesis):

- 又称代谢产热,指体内发生广泛的代谢产热增加。以褐色脂肪组织的产热量最大,约占非战栗产热总量的70%。

主要散热途径

动物的主要散热部位是皮肤;(75~85%)

其他的散热途径还有呼吸器官、消化器官和排尿等

热喘呼吸是炎热条件下增加蒸发散热的一种形式,即呼吸频率升高到200~400次的张口呼吸,呼吸深度减小,因而潮气量减少,气体在无效腔中快速流动,唾液分泌有明显增加,所以热喘呼吸时,不会发生通气过度和呼吸性碱中毒。

2. 体温恒定的调节

动物机体体温的调节主要有两种形式:

- 自主调节:下丘脑的体温调节中枢通过对产热和散热的调节而使体温维持恒定。

- 行为调节:指动物通过自身行为的改变以控制散热和产热的程度,维持体温的恒定。

出汗对调节散热有明显的畜种差异:

- 马属动物: 能大量出汗;

- 牛:有中等程度的出汗能力;

- 绵羊:可发汗,但热喘呼吸是主要散热方式;

- 狗:几乎全部依靠热喘呼吸散热;

- 啮齿动物:即不热喘呼吸也不发汗,它们向毛上吐抹唾液或水来蒸发散热。

温度感受器

外周温度感受器 - 广泛分布于皮肤、粘膜和内脏

- 冷感受器

- 热感受器

中枢温度感受器 - 脊髓、延髓、脑干网状结构等处

- 热敏神经元 (warm-sensitive neuron)

- 冷敏神经元(cold-sensitiveneuron)

体温调节中枢

体温调节的基本中枢位于下丘脑

视前区-下丘脑前部(preoptic-anterior hypothalamus area,PO/AH)是体温调节中枢的关键部位

- PO/AH is an acronym for preoptic anterior hypothalamus, the part of the brain that senses core body temperature and regulates it to about 36.8 °C (98.6 °F).

信号传出途径与效应器

- 自主神经系统(ANS)【植物性神经系统】

- 主要通过对血管、呼吸、皮肤、汗腺和代谢的影响。

- 躯体神经系统

- 主要控制骨骼肌的紧张性和运动

- 内分泌系统

- 通过分泌甲状腺激素和肾上腺皮质激素等

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), formerly the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the peripheral nervous system that supplies smoothmuscle and glands, and thus influences the function of internal organs.

The somatic nervous system (SNS or voluntary nervous system) is the part of the peripheral nervous system associated with the voluntary control of body movements via skeletal muscles.

体温调定点学说:

- 在PO/AH区中有一个控制体温的调定点,而PO/AH区的温度敏感神经元可能起调定点的结构基础。hypothalamic

- 当体温处于调定点时,机体的产热和散热过程处于平衡状态,体温维持在调定点设定的水平。

Questions

- Describe how body temperature is regulated.

- What are the implications for global warming on animals?