L11 Autistic, Attention-deficit, Stress

一、Autistic Disorder 自闭症

Description

When a baby is born, the parents normally expect to love and cherish the child and to be loved and cherished in return. Unfortunately, some infants are born with a disorder that impairs their ability to return their parents’ affection.

Autistic disorder

- A chronic disorder whose symptoms include:

- failure to develop normal social relations with other people,

- impaired development of communicative ability,

- the presence of repetitive, stereotyped movements.

- Most people with autistic disorder display cognitive impairments.

The syndrome was named and characterized by Kanner (1943), who chose the term (auto, “self,”-ism, “condition”) to refer to the child’s apparent self-absorption.

According to a review by Silverman et al. (2010), the incidence of autistic disorder is 0.6–1.0% in the population.

- The disorder is 4 times more common in males than in females.

- However, if only cases of autism with mental retardation are considered, the ratio falls to 2:1, and if only cases of high-functioning autism are considered (those with average or above-average intelligence and reasonably good communicative ability), the ratio rises to approximately 7:1.

- These data suggest that the social impairments are much more common in males but the cognitive and communicative impairments are more evenly shared by males and females.

Autistic disorder is one of several pervasive developmental disorders that have similar symptoms.

Asperger’s syndrome 阿斯伯格综合征

- Asperger’s syndrome, the mildest form of autistic spectrum disorder, is generally less severe than autistic disorder, and its symptoms do not include a delay in language development or the presence of important cognitive deficits.

- The primary symptoms of Asperger’s syndrome are deficient or absent social interactions and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors along with obsessional interest in narrow subjects.

Rett’s disorder

- Rett’s disorder is a genetic neurological syndrome seen in girls that accompanies an arrest of normal brain development that occurs during infancy.

Childhood disintegrative disorder

- Children with childhood disintegrative disorder show normal intellectual and social development and then, sometime between the ages of two and ten years, show a severe regression into autism.

According to the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV), a diagnosis of autistic disorder requires the presence of three categories of symptoms:

- impaired social interactions,

- absent or deficient communicative abilities,

- and the presence of stereotyped behaviors.

Social impairments(社交障碍) are the first symptoms to emerge. Infants with autistic disorder do not seem to care whether they are held, or they may arch their backs when picked up, as if they do not want to be held. They do not look or smile at their caregivers. If they are ill, hurt, or tired, they will not look to someone else for comfort. As they get older, they do not enter into social relationships with other children and avoid eye contact with them. They have difficulty predicting other people’s behavior or understanding their motivations. In severe cases, autistic people do not even seem to recognize the existence of other people.

The language development(语言障碍) of people with autism is abnormal or even nonexistent. They often echo what is said to them, and they may refer to themselves as others do—in the second or third person.

Autistic people generally show abnormal interests and behaviors. For example, they may show stereotyped movements, such as flapping their hand back and forth or rocking back and forth. They may become obsessed with investigating objects, sniffing them, feeling their texture, or moving them back and forth. They may become attached to a particular object and insist on carrying it around with them. They may become preoccupied in lining up objects or in forming patterns with them, oblivious to everything else that is going on around them. They often insist on following precise routines and may become violently upset when they are hindered from doing so. They show no make-believe play and are uninterested in stories that involve fantasy. Although most autistic people are mentally retarded, not all are; and unlike most retarded people, they may be physically adept and graceful. Some have isolated skills, such as the ability to multiply two four-digit numbers very quickly, without apparent effort.

Possible Causes

When Kanner first described autism, he suggested that it was of biological origin; but not long afterward, influential clinicians argued that autism was learned. More precisely, they said, it was taught—by cold, insensitive, distant, demanding, introverted parents.

Bettelheim (1967) believed that autism was similar to the apathetic, withdrawn, and hopeless behavior seen in some of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps of World War II. You can imagine the guilt felt by parents who were told by a mental health professional that they were to blame for their child’s pitiful condition. Some professionals saw the existence of autism as evidence for child abuse and advocated that autistic children be removed from their families and placed with foster parents.

Nowadays, researchers and mental health professionals are convinced that autism is caused by biological factors and that parents should be given help and sympathy, not blame.

Careful studies have shown that the parents of autistic children are just as warm, sociable, and responsive as other parents (Cox et al., 1975).

1. Heritability

Evidence indicates that autism is strongly heritable. The best evidence for genetic factors comes from twin studies.

Genetic studies indicate that autistic disorder can be caused by a wide variety of rare mutations, especially those that interfere with neural development and communication (Betancur, Sakurai, and Buxbaum, 2009).

2. Brain Pathology

Evidence suggests that approximately 20% of all cases of autism have definable biological causes.

- Evidence indicates significant abnormalities in the development of the brains of autistic children.

Although the autistic brain is, on average, slightly smaller at birth, it begins to grow abnormally quickly, and by 2–3 years of age it is about 10% larger than a normal brain.

- Following this early spurt, the growth of the autistic brain slows down, so by adolescence it is only about 1–2% larger than normal.

- The regions that appear to be most involved in the functions that are impaired in autism show the greatest growth early in life and the slowest growth between early childhood and adolescence.

- For example, the frontal cortex and temporal cortex of the autistic brain grow quickly during the first two years of life but then show little or no increase in size during the next four years, whereas these two regions grow by 20% and 17%, respectively, in normal brains.

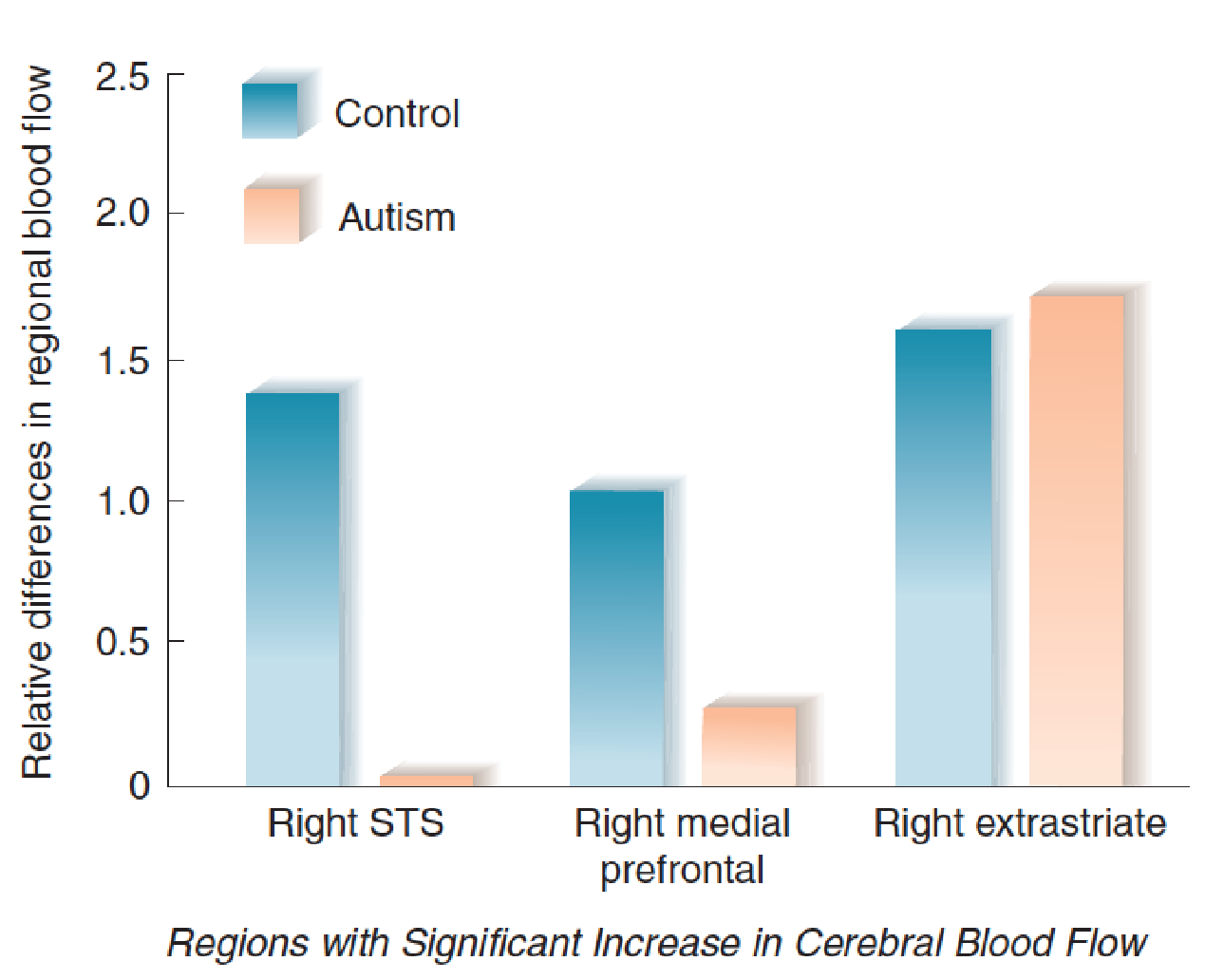

Functional imaging during presentation of various animations showed normal activation of early levels of the visual association cortex (the extrastriate cortex), but activation of the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and the medial prefrontal cortex was much lower in members of the autism group.

Inferring Intentions:

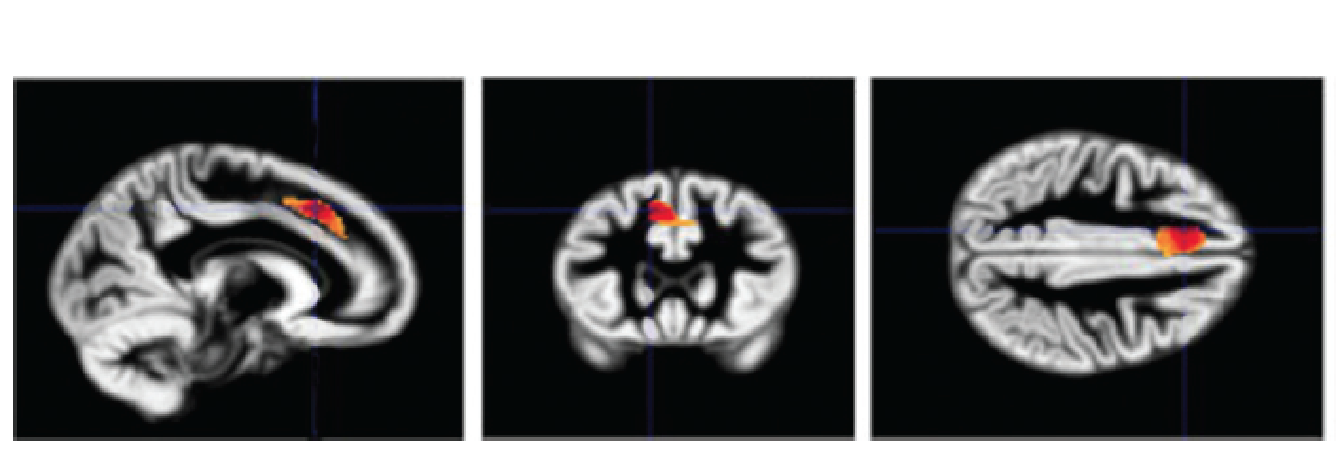

- The graph shows relative activation of specific brain regions of autistic adults and normal control subjects viewing animations of two triangles moving interactively with implied intentions.

For example, Castelli et al. (2002) showed animations that depicted two triangles interacting in various goal-directed ways (for example, simply chasing or fighting) or in a way that suggested that one triangle was trying to trick or coax the other.

For example, one normal subject described an animation in this way: “Triangles cuddling inside the house. Big wanted to persuade little to get out. He didn’t want to . . . cuddling again” . People in the autism group were able to accurately describe the goal-directed interactions of the triangles, but they had difficulty accurately describing the “intentions” of a triangle trying to trick or coax the other.

Functional imaging during presentation of the animations showed normal activation of early levels of the visual association cortex (the extrastriate cortex), but activation of the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and the medial prefrontal cortex was much lower in members of the autism group.

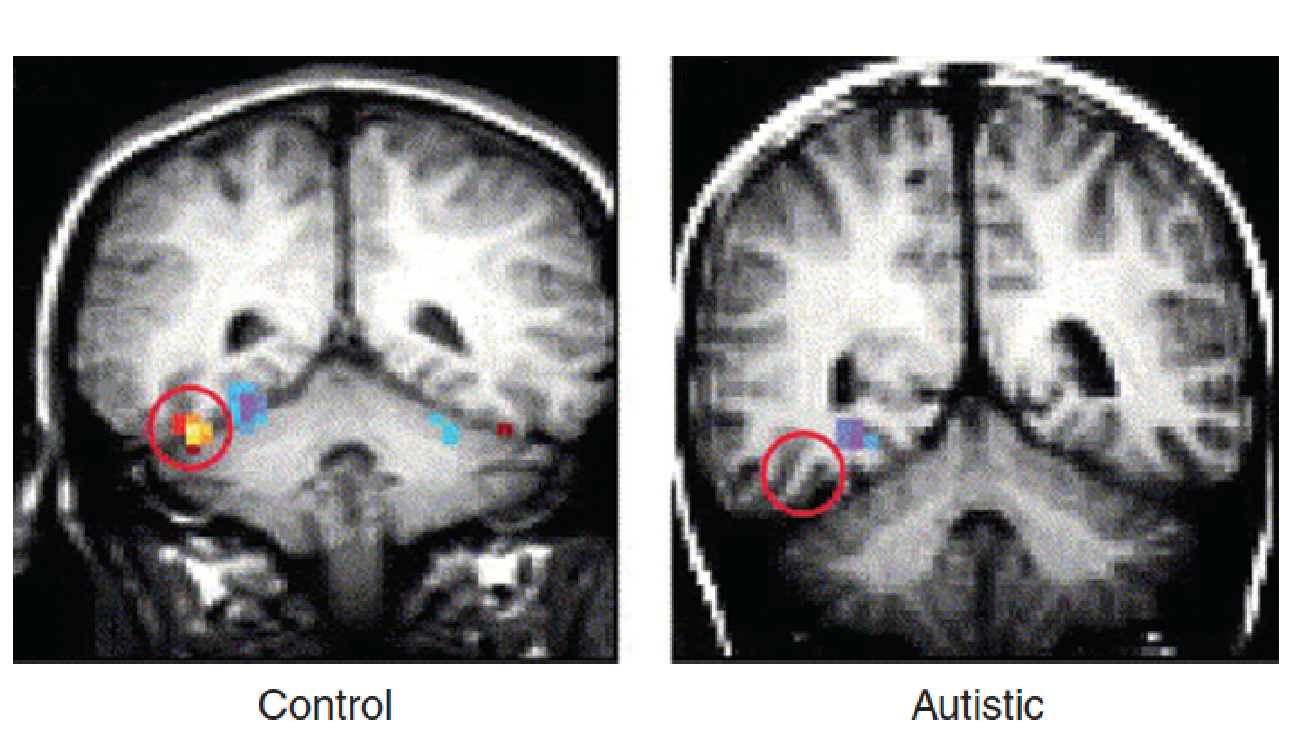

The lack of interest in or understanding of other people is reflected in the response of the autistic brain to the sight of the human face.

The fusiform face area (FFA), located on a region of visual association cortex on the base of the brain, is involved in the recognition of individual faces.

A functional imaging study by Schultz (2005) found little or no activity in the fusiform face area of autistic adults looking at pictures of human faces.

Fusiform Face Area and Autism:

- The scans show activation of the fusiform face area of control subjects but not of autistic subjects while looking at pictures of human faces.

Oxytocin, a peptide that serves as a hormone and neuromodulator, facilitates pair bonding and increases trust and closeness to others.

- Modahl et al. (1998) reported that autistic children had lower levels of this peptide.

Studies suggest that oxytocin can improve sociability of people with ASD.

Guastella et al. (2010a) found that administration of oxytocin increased the performance of adolescent males with ASD on a test of emotional recognition.

Andari et al. (2010) found that oxytocin improved the performance of adults with high-functioning ASD on a computerized ball-toss game that required social interactions with fictitious partners.

Baron-Cohen (2002) noted that the behavioral characteristics of people with autistic spectrum disorders appear to be exaggerations of the traits that tend to be associated with males.

- In fact, the incidence of autistic spectrum disorders is four times more prevalent in males, and that of Asperger’s disorder, in particular, nine times more prevalent.

- Baron-Cohen suggested that these disorders may be a reflection of an “extreme male brain.”

For example, he noted that on average, females are better than males at inferring the thoughts or intentions of others, are more sensitive to facial expressions, are more likely to respond empathetically to the distress of others, and are more likely to share with others and take turns with them.

- On average, males are less likely to display these characteristics, and they are more likely to compete with their peers, to engage in rough-and-tumble play, and to establish dominance hierarchies. Males also tend to show more interest in toy vehicles, weapons, and building blocks and in pursuits such as engineering, metalworking, and computer programming. They are also generally better at map reading. In other words, males generally exhibit more interest in working with physical objects and logical systems than with social relations.

According to Baron-Cohen, people with autistic spectrum disorders show an exaggerated pattern of masculine interests and behaviors. For example, the lack of interest in other people and an obsession with counting and lining-up objects in a row that is seen in many people with autism are seen as extreme examples of masculine traits.

Sexual differentiation of the brain is largely controlled by exposure to prenatal androgens.

Even if Baron-Cohen’s hypothesis is correct, we cannot conclude that autism is caused by prenatal exposure to excessive amounts of testosterone.

An “extreme masculine brain” could be caused by genetic abnormalities that increase the sensitivity of a developing brain to androgens, and there could be (and probably are) other causes of autism that have nothing to do with masculinization of the brain.

二、Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Description

Some children have difficulty concentrating, remaining still, and working on a task. At one time or another, most children exhibit these characteristics. But children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) display these symptoms so often that they interfere with the children’s ability to learn.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) 注意缺陷多动症

- A disorder characterized by uninhibited responses, lack of sustained attention, and hyperactivity; first shows itself in childhood.

- ADHD is the most common behavior disorder that shows itself in childhood.

It is usually first discovered in the classroom, where children are expected to sit quietly and pay attention to the teacher or work steadily on a project.

They have difficulty withholding a response, act without reflecting, often show reckless and impetuous behavior, and let interfering activities intrude into ongoing tasks.

According to the DSM-IV, the diagnosis of ADHD requires the presence of six or more of nine symptoms of inattention and six or more of nine symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity that have persisted for at least six months.

Symptoms of inattention include such things as “often had difficulty sustaining attention in tasks of play activities” or “is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli.”

Symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity include such things as “often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate” or “often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)”

It is seen in 4–5% of grade school children. Boys are about 10 times more likely than girls to receive a diagnosis of ADHD, but in adulthood the ratio is approximately 2 to 1, which suggests that many girls with this disorder fail to be diagnosed.

Because the symptoms can vary—some children’s symptoms are primarily those of inattention, some are those of hyperactivity, and some show mixed symptoms—most investigators believe that this disorder has more than one cause.

Diagnosis is often difficult, because the symptoms are not well defined. ADHD is often associated with aggression, conduct disorder, learning disabilities, depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.

The most common treatment for ADHD is administration of methylphenidate (Ritalin), a drug that inhibits the reuptake of dopamine.

Possible Causes

There is strong evidence from both family studies and twin studies for hereditary factors that play a role in determining a person’s likelihood of developing ADHD.

The estimated heritability of ADHD ranges from 75 – 91% (Thapar, O’Donovan, and Owen, 2005).

The symptoms of ADHD resemble those produced by damage to the prefrontal cortex: distractibility, forgetfulness, impulsivity, poor planning, and hyperactivity (Aron, Robbins, and Poldrack, 2004).

The prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in short-term memory. We use short-term memory to remember what we have just perceived, to remember information that we have just recalled from long-term memory, and to process (“work on”) all of this information. For this reason, short-term memory is often referred to as working memory. The prefrontal cortex uses working memory to guide thoughts and behavior, regulate attention, monitor the effects of our actions, and organize plans for future actions (Arnsten, 2006).

- Damage or abnormalities in the neural circuits that perform these functions give rise to the symptoms of ADHD.

As we saw earlier, the fact that dopamine antagonists were discovered to reduce the positive symptoms of schizophrenia suggested the hypothesis that schizophrenia is caused by overactivity of dopaminergic transmission.

Similarly, the fact that methylphenidate, a dopamine agonist, alleviates the symptoms of ADHD has suggested the hypothesis that this disorder is caused by underactivity of dopaminergic transmission.

Normal functioning of the prefrontal cortex is impaired by low levels of dopamine receptor stimulation in this region, so the suggestion that abnormalities in dopaminergic transmission play a role in ADHD seems reasonable.

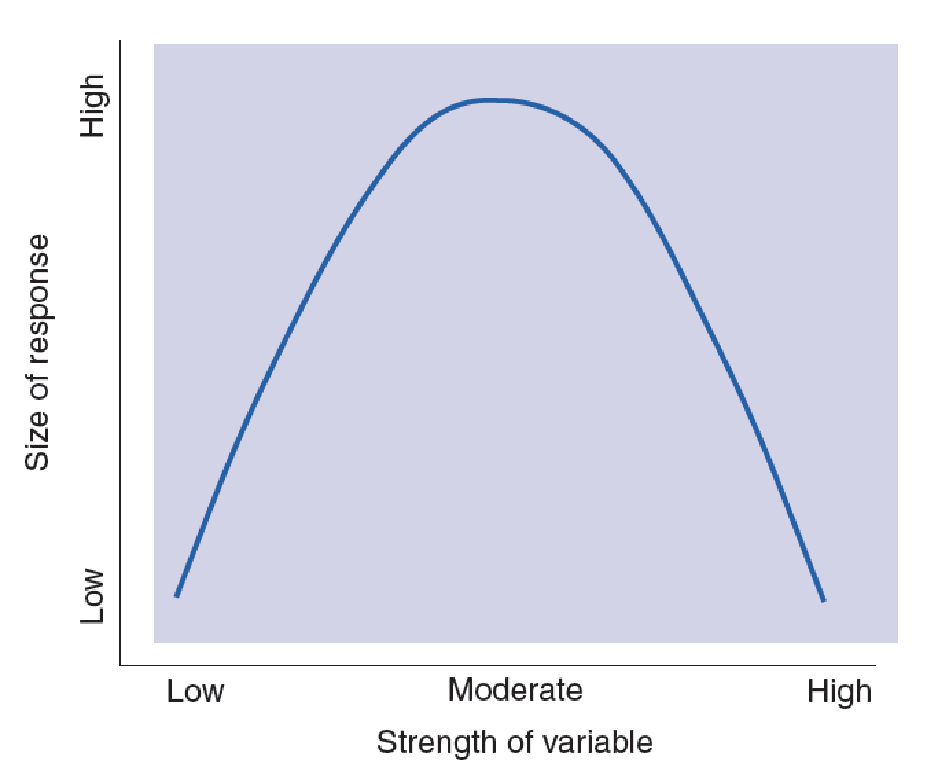

Many studies have shown that the effect of dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex on the functions of this region follow an inverted U-shaped curve.

Graphs of many behavioral functions have an inverted U shape. For example, moderate levels of motivation increase performance on most tasks, but very low levels fail to induce a person to perform, and very high levels tend to make people nervous and interfere with their performance.

The dose-response curve for the effects of methylphenidate also follow an inverted U-shaped function: Doses that are too low are ineffective, and doses that are too high produce increases in activity level that disrupt children’s attention and cognition.

In fact, a moderate dose of methylphenidate increased the responsiveness of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of rats. However, high dose of methylphenidate profoundly suppressed neural activity.

- The graph illustrates an inverted (upside-down) U-curve function.

- The relation between brain dopamine levels and the symptoms of ADHD follow a function like this one.

三、Stress Disorders 应激障碍

Walter Cannon, a prominent twentieth-century physiologist, introduced the term stress to refer to the physiological reaction caused by the perception of aversive or threatening situations.

- The physiological responses that accompany the negative emotions prepare us to threaten rivals or fight them or to run away from dangerous situations.

Cannon introduced the phrase fight-or-flight response to refer to the physiological reactions that prepare us for the strenuous efforts required by fighting or running away.

Normally, once we have bluffed or fought with an adversary or run away from a dangerous situation, the threat is over and our physiological condition can return to normal. The fact that the physiological responses may have adverse long-term effects on our health is unimportant as long as the responses are brief. But sometimes, the threatening situations are continuous rather than episodic, producing a more or less continuous stress response.

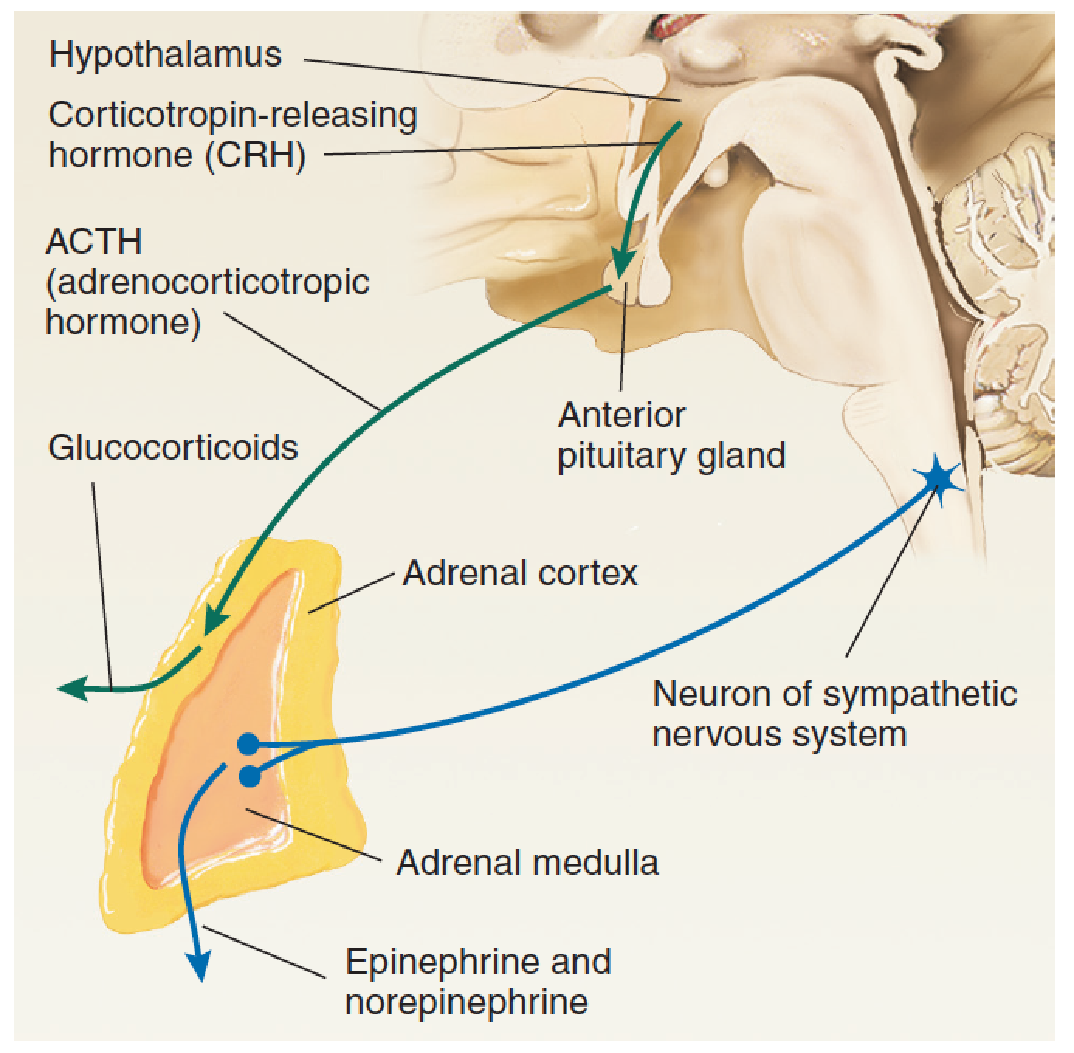

Physiology of the Stress Response

Emotions consist of behavioral, autonomic, and endocrine responses.

The latter two components, the autonomic and endocrine responses, are the ones that can have adverse effects on health.

Because threatening situations generally call for vigorous activity, the autonomic and endocrine responses that accompany them are catabolic; that is, they help to mobilize the body’s energy resources.

The sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system is active, and the adrenal glands secrete epinephrine, norepinephrine, and steroid stress hormones.

Epinephrine affects glucose metabolism, causing the nutrients stored in muscles to become available to provide energy for strenuous exercise. Along with norepinephrine, the hormone also increases blood flow to the muscles by increasing the output of the heart. In doing so, it also increases blood pressure, which, over the long term, contributes to cardiovascular disease.

Health Effects of Long-Term Stress

Besides serving as a stress hormone, norepinephrine is secreted in the brain as a neurotransmitter. Some of the behavioral and physiological responses produced by aversive stimuli appear to be mediated by noradrenergic neurons.

For example, microdialysis studies have found that stressful situations increase the release of norepinephrine in the hypothalamus, frontal cortex, and lateral basal forebrain. Presumably, this stress-induced release is controlled by a pathway from the central nucleus of the amygdala to the locus coeruleus, the nucleus of the brain stem that contains NE-secreting neurons.

The other stress-related hormone is cortisol, a steroid secreted by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol is also called a glucocorticoid because it has profound effects on glucose metabolism.

- Glucocorticoids help to break down protein and convert it to glucose, help to make fats available for energy, increase blood flow, and stimulate behavioral responsiveness, presumably by affecting the brain.

- They decrease the sensitivity of the gonads to luteinizing hormone (LH), which suppresses the secretion of the sex steroid hormones.

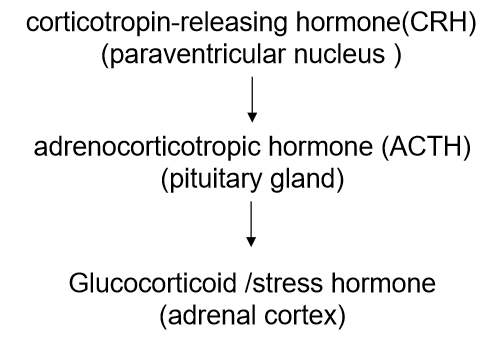

Control of Secretion of Stress Hormones :

- The diagram illustrates control of the secretion of glucocorticoids by the adrenal cortex and of catecholamines by the adrenal medulla.

The behavioral effects produced by an injection of CRH into the brain are similar to those produced by aversive situations.

For example, intracerebroventricular injection of CRH decreases the amount of time a rat spends in the center of a large open chamber, enhances the acquisition of a classically conditioned fear response, and increases the startle response elicited by a sudden loud noise.

On the other hand, intracerebroventricular injection of a CRH antagonist reduces the anxiety caused by a variety of stressful situations.

The secretion of glucocorticoids does more than help an animal react to a stressful situation: It helps the animal to survive.

If a rat’s adrenal glands are removed, the rat becomes much more susceptible to the effects of stress. In fact, a stressful situation that a normal rat would take in stride might kill one whose adrenal glands have been removed. And physicians know that if an adrenalectomized person is subjected to stressful situations, he or she must be given additional amounts of glucocorticoid.

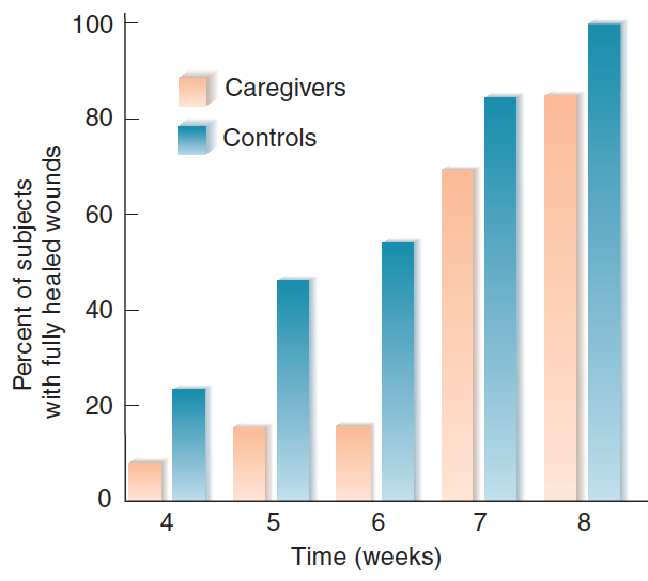

Many studies of people who have been subjected to stressful situations have found evidence of ill health.

- The short-term effects of glucocorticoids are essential, the long-term effects are damaging.

A pioneer in the study of stress, Hans Selye, suggested that most of the harmful effects of stress were produced by the prolonged secretion of glucocorticoids (Selye, 1976).

Although the short-term effects of glucocorticoids are essential, the long-term effects are damaging.

These effects include increased blood pressure, damage to muscle tissue, steroid diabetes, infertility, inhibition of growth, inhibition of the inflammatory responses, and suppression of the immune system.

High blood pressure can lead to heart attacks and stroke. Inhibition of growth in children who are subjected to prolonged stress prevents them from attaining their full height. Inhibition of the inflammatory response makes it more difficult for the body to heal itself after an injury, and suppression of the immune system makes an individual vulnerable to infections.

Stress and Healing of Wounds:

- The graph shows the percentage of caregivers and control subjects whose wounds had healed as a function of time after the biopsy was performed.

Effects of Stress on the Brain

Sapolsky and his colleagues (Sapolsky, 1992, 1995; McEwen and Sapolsky, 1995) have investigated one rather serious long-term effect of stress: brain damage.

The hippocampal formation plays a crucial role in learning and memory, and evidence suggests that one of the causes of memory loss that occurs with aging is degeneration of this brain structure.

- Research with animals has shown that long-term exposure to glucocorticoids destroys neurons located in field CA1 of the hippocampal formation.

Perhaps, then, the stressful stimuli to which people are subjected throughout their lives increase the likelihood of memory problems as they grow older.

Brunson et al. (2005) confirmed that stress early in life can cause the deterioration of normal hippocampal functions later in life.

During the first week after delivery, the investigators placed female rats and their newborn pups in cages with hard floors and only a small amount of nesting material. When the animals were tested at 4–5 months of age, their behavior was normal. However, when they were tested at 12 months of age, the investigators observed impaired performance in the Morris water maze and deficient development of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. They also found dendritic atrophy in the hippocampus, which might have accounted for the impaired spatial learning and synaptic plasticity.

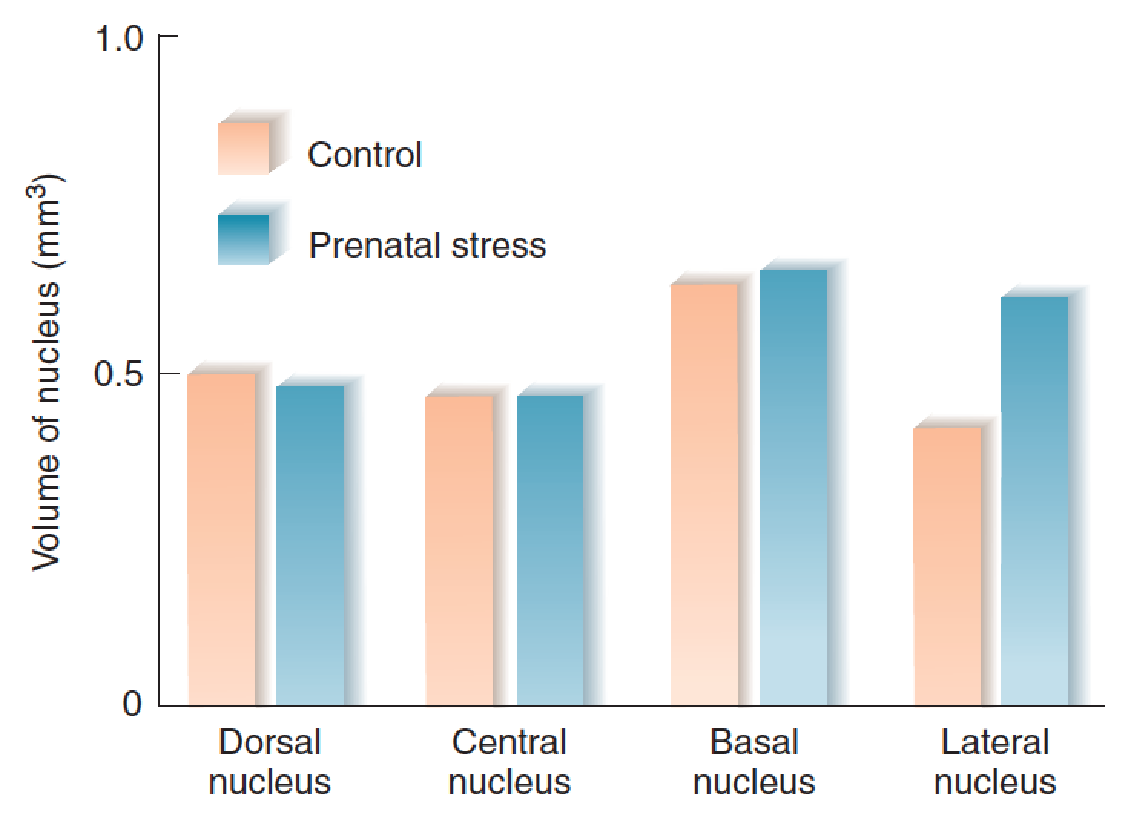

Salm et al. (2004) found that brief episodes of prenatal stress can affect brain development and produce changes that last the animal’s lifetime.

Once a day during the last week of gestation, they removed pregnant rats from their cage and gave them an injection of a small amount of sterile saline—a procedure that lasted less than five minutes.

- This stress altered the development of their amygdalas. The investigators found that the volume of the lateral nucleus of the amygdala, measured in adulthood, was increased by approximately 30 percent in the animals that sustained prenatal stress. As previous experiments have shown, prenatal stress increases fearfulness in a novel environment. Presumably, the increased size of the lateral nucleus contributes to this fearfulness.

A study by Fenoglio, Chen, and Baram (2006) found that experiences that occur during early life can reduce reactivity to stressful situations in adulthood.

Fenoglio and her colleagues removed rat pups from their cage, handled them for fifteen minutes, and then returned them to their cage. Their mother immediately began licking and grooming the pups. This nurturing behavior activated several regions of the pups’ brains, including the central nucleus of the amygdala and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the location of neurons that secrete CRH. This treatment was designed to reduce the production of CRH in response to stressful stimuli, which conferred a lifelong attenuation of the hormonal stress response.

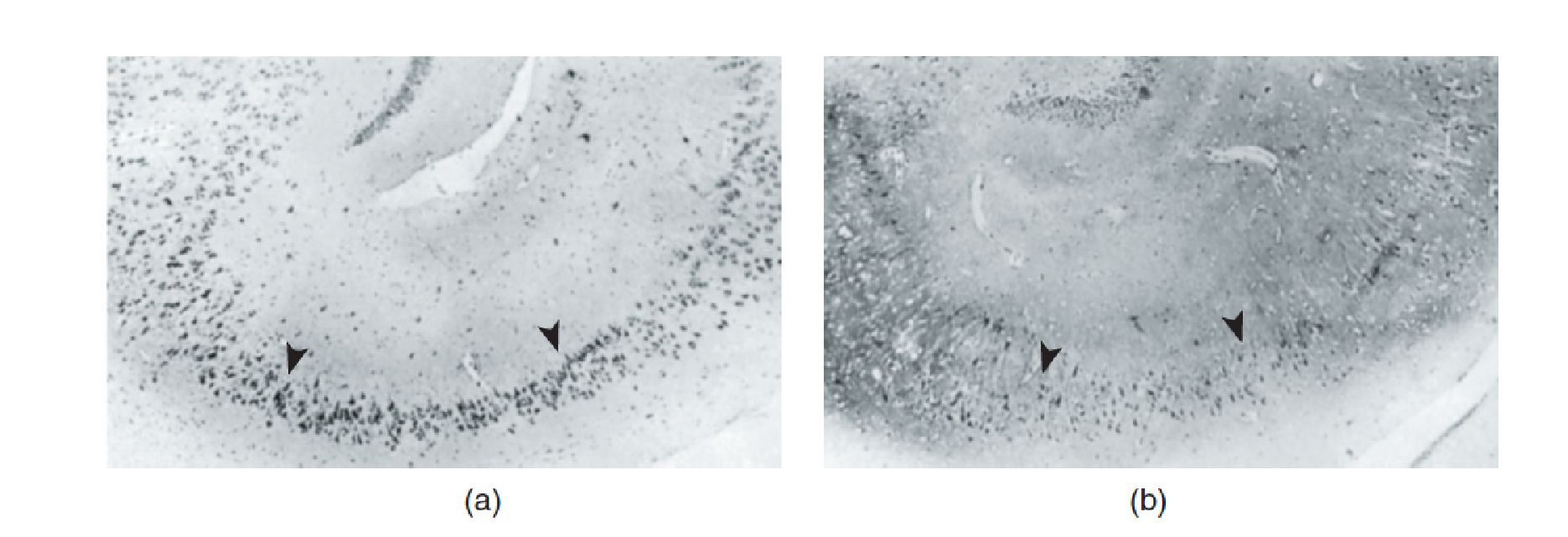

Uno et al. (1989) found that if long-term stress is intense enough, it can even cause brain damage in young primates. The investigators studied a colony of vervet monkeys housed in a primate center in Kenya. They found that some monkeys died, apparently from stress. Vervet monkeys have a hierarchical society, and monkeys near the bottom of the hierarchy are picked on by the others; thus, they are almost continuously subjected to stress. The deceased monkeys had gastric ulcers and enlarged adrenal glands, which are signs of chronic stress.

- Neurons in the CA1 field of the hippocampal formation were completely destroyed.

- The photomicrographs show sections through the hippocampus. (a) A normal monkey. (b) A monkey of low social status subjected to stress. Compare the regions between the arrowheads, which are normally filled with large pyramidal cells.

Severe stress appears to cause brain damage in humans as well; Jensen, Genefke, and Hyldebrandt (1982) found evidence of brain degeneration in CT scans of people who had been subjected to torture. More mild forms of stress early in life also appear to affect brain development. van Harmelen et al. (2010) found that episodes of emotional maltreatment during childhood were associated with an average 7.2 percent reduction in the volume of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

Early Stress and the Prefrontal Cortex:

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The aftermath of tragic and traumatic events such as those that accompany wars and natural disasters often includes psychological symptoms that persist long after the stressful events are over.

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- A psychological disorder caused by exposure to a situation of extreme danger and stress; symptoms include recurrent dreams or recollections; can interfere with social activities and cause a feeling of hopelessness.

Evidence from twin studies suggest that genetic factors play a role in a person’s susceptibility to develop PTSD.

A few studies have identified several specific genes as possible risk factors for developing PTSD. These genes include those responsible for the production of dopamine D2 receptors, dopamine transporters, and 5-HT transporters.

The risk for PTSD appears to depend on both genetic and environmental factors.

People with a particular allele of the gene responsible for the production of COMT, the enzyme that destroys catecholamines present in the interstitial fluid, were more likely to develop PTSD. This allele (the Val158Met polymorphism) is associated with slower destruction of catecholamines, which supports the conclusion from other research that these neurotransmitters are associated with the deleterious effects of stress.

Several studies have found evidence that the amygdala is responsible for emotional reactions in people with PTSD and that the prefrontal cortex plays a role in these reactions in people without PTSD by inhibiting the activity of the amygdala.

For example, a functional imaging study by Shin et al. (2005) found that when shown pictures of faces with fearful expressions, people with PTSD show greater activation of the amygdala and smaller activation of the prefrontal cortex than did people without PTSD.

2. Therapy

The most common treatments for PTSD are cognitive behavior therapy, group therapy, and SNRIs.

Boggio et al. (2010) report on the results of a clinical trial of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on thirty patients with PTSD.

They found that ten sessions of stimulation of the left or right dlPFC significantly reduced the symptoms of PTSD, and that the beneficial effects were still seen three months later.

Summary

As we have seen, long-term stress can be harmful to one’s health and can even result in brain damage.

The most important cause of these effects is elevated levels of glucocorticoids, but the high blood pressure caused by epinephrine and norepinephrine also plays a contributing role.

In addition, the stress response can impair the functions of the immune system, which protects us from assault from viruses, microbes, fungi, and other types of parasites.

A wide variety of stress-producing events in a person’s life can increase the susceptibility to illness.

Chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) is currently the most commonly used, reliable, and effective rodent model of depression: